Abstract

Objective

For general practitioners (GPs) dizziness is a challenging condition to deal with. Data on the management of dizziness in older patients are mostly lacking. Furthermore, it is unknown whether GPs attempt to decrease Fall Risk Increasing Drugs (FRIDs) use in the management of dizziness in older patients. The aim of this study is to gain more insight into GP’s management of dizziness in older patients, including FRID evaluation and adjustment.

Design

Data were derived from electronic medical records, obtained over a 12-month period in 2013.

Setting

Forty-six Dutch general practices.

Patients

The study sample comprised of 2812 older dizzy patients of 65 years and over. Patients were identified using International Classification of Primary Care codes and free text.

Main outcome measures

Usual care was categorized into wait-and-see strategy (no treatment initiated); education and advice; additional testing; medication adjustment; and referral.

Results

Frequently applied treatments included a wait-and-see strategy (28.4%) and education and advice (28.0%). Additional testing was performed in 26.8%; 19.0% of the patients were referred. Of the patients 87.2% had at least one FRID prescription. During the observation period, GPs adjusted the use of one or more FRIDs for 11.7% of the patients.

Conclusion

This study revealed a wide variety in management strategies for dizziness in older adults. The referral rate for dizziness was high compared to prior research. Although many older dizzy patients use at least one FRID, FRID evaluation and adjustment is scarce. We expect that more FRID adjustments may reduce dizziness and dizziness-related impairment.

Key Points

It is important to know how general practitioners manage dizziness in older patients in order to assess potential cues for improvement.

This study revealed a wide variety in management strategies for dizziness in older patients.

There was a scarcity in Fall Risk Increasing Drug (FRID) evaluation and adjustment.

The referral rate for dizziness was high compared with previous research.

Keywords: Aged, dizziness, drug prescriptions, general practice, therapy, The Netherlands

Introduction

For general practitioners (GPs) dizziness is a challenging condition to deal with: dizziness may refer to a variety of sensations and the complaint dizziness may accompany harmless but also very serious conditions. Dizziness can refer to several sensations including a giddy or rotational sensation, a loss of balance, a faint feeling, light-headedness, instability or unsteadiness, a tendency to fall, or a feeling of everything turning black.[1] There is a broad etiologic spectrum of peripheral, central (neurological), and general medical causes for dizziness. Furthermore, several authors suggest that dizziness in older people might be a multifactorial geriatric syndrome.[2–6] A geriatric syndrome is defined as a specific symptom that is caused by multiple underlying factors, involving multiple organ systems that tend to contribute to the geriatric syndrome.[7]

It is important to know how GPs manage dizziness in older patients, in order to assess potential cues for improvement. Only few studies focused on the management of dizziness in primary care but these studies did not focus on older patients.[8–12]

A medication review should be part of the assessment of older patients with dizziness because it is assumed that medication is a contributory factor to dizziness in as much as 25% of these patients.[13] However, it is unknown whether GPs consider if medication might contribute to the dizziness when they evaluate an older patient. Drugs that contribute to dizziness [14,15] demonstrate a striking similarity with the list of Fall Risk Increasing Drugs (FRIDs).[16] This similarity might be explained by the fact that dizziness increases the risk of falling [17] and FRIDs are known to affect postural control.[18] Therefore, the list of FRIDs might be a useful proxy for potential dizziness inducing medication. Recently, Harun and Agrawal recommended to reconsider the use of FRIDs when evaluating and treating dizzy patients.[19]

The aim of this study is to gain more insight into the management of dizziness in older adults in general practice, with a focus on FRID evaluation and adjustment.

Material and methods

We used anonymized data from the database of the Academic Network of General Practice of VU University Medical Center (ANH-VUmc). The ANH-VUmc is a collaboration between VU University Medical Center and general practices located in an urban area of the Netherlands. The ANH-VUmc database contains anonymized routine health care data. Observational studies based on the ANH-VUmc database are carried out according to Dutch privacy legislation and are exempted from informed consent of patients.

Identification of patients

An electronic search strategy was applied to identify our target population: all patients aged 65 years and above who visited their GP because of dizziness in 2013. The database was searched for International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) codes N17 “vertigo/dizziness” and H82 “vertiginous syndrome”. Additionally, we searched for dizziness in the full text records by searching for the Dutch equivalents of “dizz*” and “vertigo”.

We extracted the following data from anonymized patient records: patient characteristics (gender, age), characteristics of consultation for dizziness (type of consultation, date, ICPC diagnosis given by the GPs), characteristics of prescribed drugs (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification, prescription date) and information on symptoms, physical examination, diagnostic evaluation, and treatment.

Reviewing electronic full-text medical records

Two authors, a medical doctor (M.S.) and a medical student (T.H.), manually reviewed the electronic full-text consultations of the identified patients. They both reviewed and discussed a randomly selected 10% of the data to increase the reliability of the data extraction.

During review, patients and consultations were excluded for several reasons: (1) patients with a consultation that mentioned dizziness when dizziness was not an actual problem for the patient were excluded (e.g. “not dizzy”); (2) if a GP was consulted through a third party (e.g. a family member); and (3) only the first three consultations for dizziness during the observation period were coded to reduce the influence of patients with many consultations.

In case of multiple consultations, the ICPC code of the second or third consultation was considered the final diagnosis. If the GP recorded two ICPC codes in the chronologically last consultation, we recorded both of the ICPC codes as final diagnosis. Treatment was categorized as follows: wait-and-see strategy (no treatment initiated); education and advice; additional testing; medication adjustment; and referral. All treatment modalities were categorized, including multiple treatment modalities in one consultation and in multiple consultations (e.g. a wait-and-see strategy and blood analysis in the first consultation and referral in the second consultation in one patient was all recorded). Category medication adjustment was only used in case of a dose reduction of FRIDs, discontinuation of FRIDs, and/or the prescription of antivertigo drugs and antiemetics. The list of FRIDs included psychotropic drugs (sedatives, antidepressants, neuroleptics), cardiovascular drugs (antihypertensives, nitrates, antiarrhythmic agents, nicotinic acid, β-adrenoceptor blocker eye drops) and other drugs (analgesics, antivertigo drugs, hypoglycemics, urinary antispasmodics).[16]

Data analysis

We used descriptive analyses to describe the study population and to categorize treatment modalities. Practice list sizes were available and prevalence rates were calculated using the mid-time population. Age groups were compared with Chi-square tests and logistic regression analysis.

Results

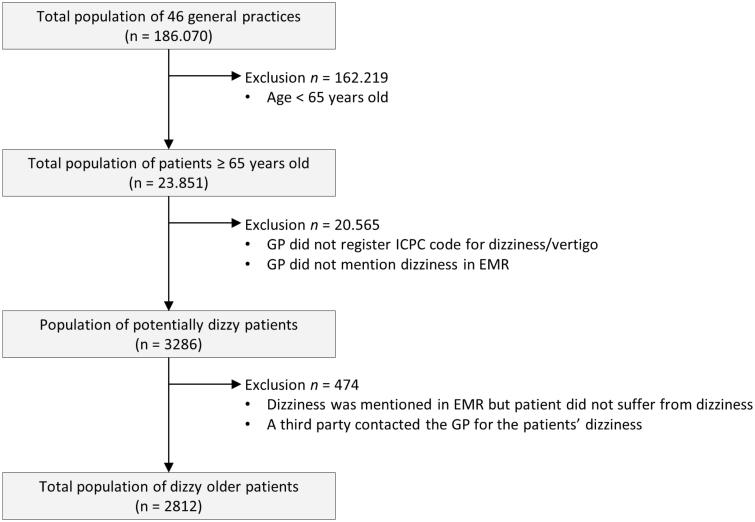

Figure 1 presents a flowchart of the study selection process. A total of 2812 older dizzy patients were included in the sample.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection process of 2812 older dizzy patients. GP: General Practitioner; EMR: Electronic Medical Record.

Table 1 presents the clinical features of the total study population of 2812 older dizzy patients. The median age of the population was 76 years (range: 65–101). The majority of the patients was female (67.3%). The 12-month prevalence of dizziness was 11.8%. The prevalence of dizziness significantly increased with age (χ2(linear-by-linear) = 354, df = 1, p < 0.001). The median consultation frequency for dizziness was 1 (range: 1–23), 444 patients (15.8%) had more than 3 consultations in the dizziness episode. The mean follow-up time after the first consultation was 199 days (range: 1–365), 94.7% of the sample could be followed up more than one month. The most frequently recorded diagnoses for dizziness were symptom diagnoses (32.0%), cardiovascular conditions (18.2%), and peripheral vestibular diseases (10.5%).

Table 1.

Overview of characteristics of 2812 older dizzy patients.

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender, female | 1892 (67.3) |

| Age in years, mean (range) | 77.0 (65–101) |

| 65–74 | 1180 (42.0) |

| 75–84 | 1086 (38.6) |

| ≥85 | 546 (19.4) |

| Diagnosisa | |

| Symptom diagnoses | 901 (32.0) |

| Cardiovascular condition | 513 (18.2) |

| Peripheral vestibular disease | 294 (10.5) |

| Infections | 135 (4.8) |

| Psychiatric condition | 73 (2.6) |

| Musculoskeletal condition | 42 (1.5) |

| Neurological conditionb | 37 (1.3) |

| Metabolic or endocrine condition | 32 (1.1) |

| Adverse effect medical agents | 29 (1.0) |

| Other | 668 (23.8) |

| No diagnosis recorded | 110 (3.9) |

Does not add up to 100% because the GPs recorded two ICPC codes for 22 patients.

excl. cerebrovascular conditions.

Table 2 provides an overview of treatment modalities. Frequently applied treatments by GPs were a strategy of wait-and-see (n = 799, 28.4%) and providing education and advice (n = 786, 28.0%). Additional tests were performed to 755 patients (26.8%), of which blood analyses (n = 622, 22.1%) were most often carried out. Medication was prescribed and adjusted in 526 patients (18.7%). Finally, 533 patients (19.0%) were referred to a medical specialist. Patients were most often referred to a neurologist (n = 136, 4.8%), cardiologist (n = 110, 3.9%), and physiotherapist (n = 65, 2.3%).

Table 2.

Overview of management of 2812 older dizzy patients.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Wait-and-see (no treatment) | |

| Total | 799 (28.4) |

| Education and advice | |

| Vestibular training exercises | 87 (3.10) |

| Breathing exercises | 5 (0.20) |

| Other education or advice | 709 (25.2) |

| Totala | 786 (28.0) |

| Additional test | |

| Blood analysis | 622 (22.1) |

| Urine analysis | 89 (3.20) |

| Electrocardiography | 65 (2.30) |

| 24-h blood pressure monitoring | 41 (1.50) |

| Other | 34 (1.20) |

| Totala | 755 (26.8) |

| Medication prescription and medication adjustment | |

| Prescription of antiemetics | 83 (3.00) |

| Prescription of antivertigo drugs | 143 (5.10) |

| in dizziness caused by Ménière’s disease | 7 (0.20) |

| in other dizziness of vestibular origin | 52 (1.80) |

| in other types of dizziness | 84 (3.00) |

| Adjustment of FRIDs | 330 (11.7) |

| dose reduction | 131 (4.70) |

| discontinuation | 219 (7.80) |

| Totala | 526 (18.7) |

| Referral | |

| Neurologist | 136 (4.80) |

| Cardiologist | 110 (3.90) |

| Physical therapist | 65 (2.30) |

| Internist | 58 (2.10) |

| Otolaryngologist | 37 (1.30) |

| Geriatrician | 25 (0.90) |

| Ophthalmologist | 19 (0.70) |

| Psychotherapist | 16 (0.60) |

| Other | 112 (4.00) |

| Totala | 533 (19.0) |

Total number of patients. As some patients had multiple tests, adjustments or referrals, the sum of individual items does not add up to the total.

BPPV: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo; FRIDs: fall risk increasing drugs.

The use of FRIDs and the frequencies of all FRID medication adjustments are displayed in Table 3. The patients were prescribed a mean of 3.1 FRIDs (SD 2.1). As many as 87.2% of the patients had at least one FRID prescription. FRID’s were adjusted in 330 patients (11.7%). GPs reduced a FRID dose for 111 patients (3.9%) and discontinued FRID for 199 patients (7.1%). For 20 patients GPs both reduced the FRID dose and discontinued a FRID. Dose reductions of FRIDs significantly increased with age (10 year odds ratio 1.36; 95% confidence interval 1.10–1.69).

Table 3.

Use, adjustments, and new prescription of FRIDs of 2812 older dizzy patients.

| Drug group | Use of FRIDs n (%)a | Dose reductions n (%)b | Discontinuation n (%)b | Newly prescribed n (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular FRIDs | ||||

| Diuretics | 1199 (42.6) | 27 (2.3) | 56 (4.7) | |

| β-Blockers | 1144 (40.7) | 35 (3.1) | 24 (2.1) | |

| Calcium channel blockers | 654 (23.3) | 19 (2.9) | 33 (5.0) | |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors | 714 (25.4) | 17 (2.4) | 19 (2.7) | |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | 620 (22.0) | 13 (2.1) | 9 (1.5) | |

| Nitrates | 343 (12.2) | 3 (0.9) | 4 (1.2) | |

| Antiarrhythmic agents | 61 (2.22) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Digoxin | 97 (3.42) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Psychotropic FRIDs | ||||

| Antivertigo drugs | 239 (8.52) | 0 (0) | 7 (2.9) | 143 (59.8) |

| Analgesics (opioids) | 524 (18.6) | 13 (2.5) | 23 (4.4) | |

| Anxiolytics and hypnotics | 815 (29.0) | 5 (0.6) | 8 (1.0) | |

| Antidepressants | 389 (13.8) | 4 (1.0) | 8 (2.1) | |

| Neuroleptics | 91 (3.22) | 2 (2.2) | 3 (3.3) | |

| α-blockers and anticholinergics | 330 (11.7) | 1 (0.3) | 14 (4.2) | |

| Hypoglycaemics | 508 (18.1) | 3 (0.6) | 3 (0.6) | |

| Antihistamines | 292 (10.4) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | |

| β-Blocker eye drops | 98 (3.52) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Other FRIDs | 471 (16.7) | 3 (0.6) | 27 (0.6) | |

| No FRID use | 359 (12.8) | na | na | na |

| Total medication adjustments | na | 131 (4.7)c | 219 (7.8)d | (140)e |

Percent of patients being prescribed at least one drug of the displayed fall risk increasing drug categories during 2013.

Percent of patients with at least one FRID adjustment per FRID group.

In 14 patients, two medications were reduced in dose, in one patient three medications were reduced in dose.

In 20 patients two medications were stopped.

In three patients two antivertigo drugs were prescribed.

FRID: Fall Risk Increasing Drug; na: not applicable.

Discussion

Principal findings

We performed this study to gain more insight into the management of dizziness in older adults in general practice. Frequent treatments included a wait-and-see strategy (28.4%) and education and advice (28.0%). Additional tests were carried out for 26.8% of the sample. For 11.7% of the patients GPs adjusted FRID prescription. The frequency of dose reductions of FRIDs significantly increased with age. GPs referred 19.0% of the older dizzy patients to specialized care.

The prevalence of dizziness was 11.8%. Cardiovascular conditions and peripheral vestibular disease were most often recorded as cause of dizziness. The GP recorded a symptom diagnosis in 32% of the patients. In 3.9% of the patients the GP did not record a diagnosis at all.

Strengths and weaknesses

Prior to this study, few studies have investigated the management of dizziness in older patients in general practice.[8–10] To our knowledge, this is the first study that investigates adjustments of FRIDs for older dizzy patients.

In the Netherlands, all patients are registered with a GP. The GP provides care and acts as a gatekeeper to specialized care. As a consequence, data presented in this study are a proper reflection of the prevalence and management of older dizzy people in general practice.

By using a dataset derived from electronic medical records (EMRs) we were able to identify a large sample of older patients with dizziness. However, we note that the quality of data depends on the accuracy of registration by GPs. Yet, GPs who participate in the general practice-based registration network where data for this study is derived from, are annually trained on registering and coding of medical data.

Findings in relation to other studies

Only a small number of studies investigated the management of dizziness in general practice.[8–11] A wait-and-see strategy was also frequently seen in a previous study with dizzy patients of both younger and older age.[9] Observation, reassurance, and advice to change behavior tended to be used in older dizzy patients in this study of Sloane et al. [9] In three studies with younger and older adults, drugs were prescribed to 60–90% of the patients,[8–10] which is much more frequent than in our sample. The high rate of referral to specialized care (19.0%) in this study is remarkable; international studies reported 4–16% referrals [8–10] and Dutch studies reported referral rates of 3.2–4.5%.[20,21] Several studies demonstrate that GPs’ referral decisions are influenced by a complex mix of patient, physician, and health care system structural characteristics.[22–24] As the Dutch health care system did not change, changes in patient’s expectations, doctor’s perceptions of patients expectations reassurance for the patient) might have influenced the referral rate. It is unknown whether the referrals were effective in achieving their objectives and whether they were cost-effective.

This is the first study that focussed on the use and adjustments of FRIDs in older dizzy patients. FRID use was quite high in our study sample, with a mean of 3.1 FRID prescriptions per patient. This is similar to the mean of FRID prescriptions in a study of older patients plus a fall history and a study with frail aged patients (3.3 and 3.4, respectively).[16,25]

GPs discontinued a FRID or reduced the dose of a FRID for 11.7% of the patients. Other management strategies were carried out in 19.0–28.4% of our sample. Compared with other management strategies, FRID adjustment was carried out the least frequent. In a qualitative study on situations in which GPs associate FRIDs with falls, drug use was often not perceived as a prominent factor.[26] One situation leading to a consideration of the drug prescribed was if a patient had fallen or presented with a symptom such as dizziness. However, the paradox of not being able to predict the outcome of changes in drug treatment was perceived as challenging and uncomfortable; the GPs believed that it might be better not to change prescriptions instead.[26] In other research on de-prescribing of medication, four main themes of doctor-related barriers are described: lack of awareness on consequences of polypharmacy; inertia or devolving of responsibility; lack of skills and knowledge; and presumed lack of feasibility.[27] Evidently, adjustment of medication seems difficult. However, given the fact that 87.2% of the patients were having at least one prescribed FRID in this sample, there is ample room for improvement by adjusting more FRID medication. A medication review, and evaluation and adjustment of FRIDs in particular, may be a simple and effective management strategy to reduce dizziness and dizziness-related impairment in older patients. FRIDs can also be adjusted if the cause of dizziness has not yet been identified.

The prevalence of dizziness in older adults seems higher than previously reported. Maarsingh et al. reported a dizziness prevalence of 8.3%, whereas this study revealed a dizziness prevalence of 11.8% in a highly comparable sample.[28] Furthermore, Sloane et al. reported a dizziness prevalence of 7.0% in patients aged 85 years and above.[8] Drug prescription has increased,[29] with higher rates of adverse drug reactions as a result. This may have resulted in a higher prevalence of dizziness in older patients, as adverse drug reactions are thought to contribute to dizziness.[13] On the other hand, GPs who participate in the general practice-based registration network where data for the current study is derived from, are annually trained on registering and coding of medical data. This may have caused higher registration rates by GPs in this study. It is important to continue monitoring whether dizziness prevalence in older adults is rising, because this will increase the burden of dizziness on society, health care systems, and individuals.

In 35.9% of this sample GPs recorded a symptom diagnosis or did not record a diagnosis at all. In a similar study, GPs recorded a symptom diagnosis in 40.0% of the patients.[28] This high rate of unknown cause of dizziness may be the result of difficulties for GPs to establish the origin of dizziness.

Meaning of the study: implications for clinicians and research

Compared with other management strategies, FRID adjustments were carried out the least. We recommend to always evaluate the use of FRIDs for older dizzy patients and to consider adjustment. The use of FRIDs should be discontinued if no health risks are involved by discontinuation or the dose of FRIDs should be reduced when discontinuation is not an option.

The referral rate for dizziness was high compared with previous research. Therefore, it is important to investigate whether referrals for dizziness are effective in achieving their objectives and whether they are cost-effective.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank J.H.K. Joosten for her assistance with the data extraction. Furthermore the authors would like to thank all the GPs who participate in the Academic Network of General Practitioners of the VU University Medical Center.

Ethical approval

The ANH-VUmc database contains anonymized routine health care data. Observational studies based on the ANH-VUmc database are carried out according to Dutch privacy legislation and are exempted from informed consent of patients.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Funding information

This study was funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development. The funding body did not and will not have any role in the design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, nor in the writing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Sloane PD, Coeytaux RR, Beck RS, et al. Dizziness: state of the science. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(Pt 2):823–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kao AC, Nanda A, Williams CS, et al. Validation of dizziness as a possible geriatric syndrome. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:72–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gassmann KG, Rupprecht R.. Dizziness in an older community dwelling population: a multifactorial syndrome. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13:278–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomez F, Curcio CL, Duque G.. Dizziness as a geriatric condition among rural community-dwelling older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15:490–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Moraes SA, Soares WJ, Ferriolli E, et al. Prevalence and correlates of dizziness in community-dwelling older people: a cross sectional population based study. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maarsingh OR, Stam H, van de Ven PM, et al. Predictors of dizziness in older persons: a 10-year prospective cohort study in the community. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, et al. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:780–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sloane PD. Dizziness in primary care. Results from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. J Fam Pract. 1989;29:33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sloane PD, Dallara J, Roach C, et al. Management of dizziness in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 1994;7:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bird JC, Beynon GJ, Prevost AT, et al. An analysis of referral patterns for dizziness in the primary care setting. Br J Gen Pract. 1998;48:1828–1832. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jayarajan V, Rajenderkumar D.. A survey of dizziness management in General Practice. J Laryngol Otol. 2003;117:599–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nazareth I, Yardley L, Owen N, et al. Outcome of symptoms of dizziness in a general practice community sample. Fam Pract. 1999;16:616–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maarsingh OR, Dros J, Schellevis FG, et al. Causes of persistent dizziness in elderly patients in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:196–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin E, Aligene K.. Pharmacology of balance and dizziness. NeuroRehabilitation. 2013;32:529–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shoair OA, Nyandege AN, Slattum PW.. Medication-related dizziness in the older adult. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2011;44:455–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van der Velde N, Stricker BHC, Pols HA, et al. Risk of falls after withdrawal of fall-risk-increasing drugs: a prospective cohort study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:232–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tinetti ME, Doucette J, Claus E, et al. Risk factors for serious injury during falls by older persons in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:1214–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Groot MH, van Campen JPCM, Moek MA, et al. The effects of fall-risk-increasing drugs on postural control: a literature review. Drug Aging. 2013;30:901–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harun A, Agrawal Y.. The use of Fall Risk Increasing Drugs (FRIDs) in patients with dizziness presenting to a neurotology clinic. Otol Neurotol. 2015;36:862–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okkes IM, Oskam SK, Lamberts H.. Van klacht naar diagnose. Episodegegevens uit de huisartspraktijk [From complaint to diagnosis. Episode data from family practice]. Couthinho: Bussum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cardol M, van Dijk L, de Jong JD, et al Tweede Nationale Studie naar ziekten en verrichtingen in de huisartspraktijk. Huisartsenzorg: wat doet de poortwachter? [Second National Study into diseases and actions in general practice: complaints and disorders in the population and in general practice]. Utrecht/Bilthoven: Nivel/RIVM; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Little P, Dorward M, Warner G, et al. Importance of patient pressure and perceived pressure and perceived medical need for investigations, referral, and prescribing in primary care: nested observational study. BMJ. 2004;328:444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forrest CB, Nutting PA, von Schrader S, et al. Primary care physician specialty referral decision making: patient, physician, and health care system determinants. Med Decis Mak. 2006;26:76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ringberg U, Fleten N, Førde OH.. Examining the variation in GPs’ referral practice: a cross-sectional study of GPs' reasons for referral. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64:e426–e433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett DA, Gnjidic D, Gillett M, et al. Prevalence and impact of fall-risk-increasing drugs, polypharmacy, and drug-drug interactions in robust versus frail hospitalised falls patients: a prospective cohort study. Drug Aging. 2014;31:225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bell HT, Steinsbekk A, Granas AG.. Factors influencing prescribing of fall-risk-increasing drugs to the elderly: a qualitative study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015;33:107–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson K, Stowasser D, Freeman C, et al. Prescriber barriers and enablers to minimising potentially inappropriate medications in adults: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e006544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maarsingh OR, Dros J, Schellevis FG, et al. Dizziness reported by elderly patients in family practice: prevalence, incidence, and clinical characteristics. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Health, United States With special feature on prescription drugs. U.S. Department of Health and Humans: Hyattsville, 2013; [cited 2015 Jun 12]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus13.pdf. [Google Scholar]