Abstract

Objective

Feedback may be scarce and unsystematic during students' clerkship periods. We wanted to explore general practitioners' (GPs) and medical students' experiences with giving and receiving supervision and feedback during a clerkship in general practice, with a focus on their experiences with using a structured tool (StudentPEP) to facilitate feedback and supervision.

Design

Qualitative study.

Setting

Teachers and students from a six-week clerkship in general practice for fifth year medical students were interviewed in two student and two teacher focus groups.

Subjects

21 GPs and nine medical students.

Results

We found that GPs first supported students' development in the familiarization phase by exploring the students' expectations and competency level. When mutual trust had been established through the familiarization phase GPs encouraged students to conduct their own consultations while being available for supervision and feedback. Both students and GPs emphasized that good feedback promoting students' professional development was timely, constructive, supportive, and focused on ways to improve. Among the challenges GPs mentioned were giving feedback on behavioral issues such as body language and insensitive use of electronic devices during consultations or if the student was very insecure, passive, and reluctant to take action or lacked social or language skills. While some GPs experienced StudentPEP as time-consuming and unnecessary, others argued that the tool promoted feedback and learning through mandatory observations and structured questions.

Conclusion

Mutual trust builds a learning environment in which supervision and feedback may be given during students' clerkship in general practice. Structured tools may promote feedback, reflection and learning.

Key Points

Observing the teacher and being supervised are essential components of Medical students' learning during general practice clerkships.

Teachers and students build mutual trust in the familiarization phase.

Good feedback is based on observations, is timely, encouraging, and instructive.

StudentPEP may create an arena for structured feedback and reflection.

Keywords: Clinical clerkship, feedback, general practice, learning, medical student, Norway

Introduction

Undergraduate medical education often involves clerkship periods in general practice.[1,2] Learning through apprenticeship is resource demanding,[3] but clerkships offer unique opportunities for individual supervision and feedback.[4] Supervision in medical clerkships should include guidance and feedback on several levels regarding the learner’s experience of providing safe and appropriate patient care.[5] The feedback given should be constructive and given in a timely manner, and has to be accepted by the student.[3] Although individual work-based assessment and feedback facilitate learning,[6] feedback may be scarce and unsystematic,[6] and often with individual teachers doing it their own personal way.[7] Video-recorded student consultations with consequent video-assisted feedback have been used for the same purpose in Germany, by using a checklist based on the clinical guideline for the specific symptom.[8] The use of video recording for giving feedback on consultations with real patients has been described as emotionally stressful for students, but rewarding afterwards.[9]

Medical students at the University of Oslo conduct a six-week clerkship in general practice during their fifth year of studies. At this stage in their education students hold a limited license to practice as a doctor, and they may see patients on their own under supervision. During the clerkship students are supervised in a one-to-one learning situation by general practitioners (GPs) who are members of the faculty. An educational tool named StudentPEP was developed to facilitate supervision and feedback during the clerkship,[10] through making direct observations of student consultations and written feedback mandatory. StudentPEP documented students’ self-assessment, scores and comments from the patient; and the GP who had observed the student for five student-led consultations. The assessment forms are described in Box 1. Originally, the students also conducted a questionnaire survey with 20 patients who had consulted them. The patient form was a modified form of the EUROPEP questionnaire.[11] We found that the tool provided specific and concrete feedback, but that clinical teachers generally could be more specific in their evaluation of students.[10] When exploring the perceived usefulness of the tool, we found that patients’ evaluations increased students' awareness of the patient perspective, and a majority of the students considered the triangulated written feedback beneficial, although time-consuming.[12] The teachers’ attitudes to the tool strongly influenced the students’ views on how useful StudentPEP was.[12] The faculty thereafter decided to simplify the tool by not requiring the separate patient survey, but give priority to the five mandatory observations with written feedback from patients, students, and teachers.

Box 1.

Description of StudentPEP.

| The StudentPEP tool is a 15-item version of EUROPEP which is a validated and reliable tool for measuring patients’ evaluation of quality in general practice. The teacher and student forms consisted mainly of open-ended questions concerning what was good and what might have been better on taking a history, performing a clinical examination, assessment and plan, but also included four of the 15 items with measures that could be compared with scores from patients (thoroughness, involving patient in decisions, explaining the purpose of tests and treatments, and physical examination). A global score for the whole consultation was added. The forms were completed after each of five teacher-observed consultations together with a patient evaluation. |

| The patient form included 15 original items from EUROPEP and a global score |

What is your opinion of the medical student regarding…

|

Global score

|

Being medical doctors with a background in general practice (S.F.G., A.M.B., M.L.) and health services research/neurology (J.C.F.) we had an interest in understanding more about factors that are important for supervision and feedback. S.F.G. and A.M.B. as young doctors had quite recently participated in such clerkships, and M.L. has long experience as a GP teacher.

We wanted to explore GPs’ and medical students’ experiences with giving and receiving supervision and feedback during a clerkship in general practice, with a focus on their experiences with using a structured tool (StudentPEP) to facilitate feedback and supervision.

Material and methods

We found that an explorative qualitative study was suitable in order to get insight into students’ and clinical teachers’ own perspectives on using the StudentPEP tool. We collected data through separate focus groups with students and GPs who were clinical teachers.

Participants

A total of 21 GPs were invited, securing variation in the sample regarding gender, age, geography, and teaching experience (Table 1). Medical students (n = 9), all in their fifth year of medical school, were recruited through e-mail invitations and snowball method where one student invited participants from her class by personal request.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants in the focus groups.

| Characteristics | n |

|---|---|

| General practitioners, all specialists | 21 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 11 |

| Female | 10 |

| Age range (years) | 43–64 |

| Years of teaching experience | 0.5–20 |

| Practice location | |

| Rural | 8 |

| Urban | 13 |

| Students, all fifth year | 9 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 5 |

| Male | 4 |

Focus group interviews

Two interview guides were developed by three of the authors (J.C.F., M.L., and S.F.G.). The interview guide for GPs was aimed at exploring their views and experiences with providing feedback, and also contained questions about barriers to giving feedback. The interview guide for students focused on students’ perspectives as to what kind of feedback was considered useful, the student’s role in the feedback process and their perception of the frames and conditions that promoted useful feedback. We did two focus group interviews with a total of 21 GPs, nine in one group and 12 in the other group, during an annual university faculty development conference. Two focus group interviews with a total of nine students, five in one group and four in the other group, were conducted 1–2 months after they had finished their clerkship in general practice. The interviews lasted for 45–60 min. The interviews were conducted by S.F.G., M.L., and J.C.F. S.F.G. participated in all interviews, J.C.F. in three interviews and M.L. in one interview. One focus group interview with GPs was conducted by the author J.C.F. who had not been involved in implementing the tool, thereby having a more neutral background. There were no differences in views that were voiced in this group compared with the other focus group with GPs. The discussions in the groups were open, and the moderators secured that all participants shared their experiences and perspectives. Critical perspectives on the StudentPEP tool were welcomed.

Data analysis

All focus group interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed in verbatim in Norwegian by a secretary. One of the authors (S.F.G.) reviewed the transcription for accuracy. The transcribed data were handled anonymously and confidential.

The material was analyzed by all authors using systematic text condensation, which is a method for thematic qualitative analysis.[13] The analysis followed four steps: (1) reading all the materials to obtain an overall impression and bracketing previous preconceptions; (2) identifying units of meaning representing different aspects of feedback processes and the StudentPEP tool, and coding for these units; (3) condensing and summarizing the contents of each of the coded groups; and (4) generalizing descriptions and concepts concerning giving and receiving feedback, and views on using StudentPEP. Quotes from the interviews were translated from Norwegian to English by the authors.

Results

We have structured our findings in four subheadings: Becoming familiarized and building trust, GPs’ approach to support students’ development toward independency, and reflections on feedback and views about the StudentPEP tool. We elaborate on these themes in further detail below.

Becoming familiarized and building trust

Many GPs started the clerkship period with letting the student observe their own consultations, being a role model, and demonstrating techniques and skills in order to enable the student to work independently. GPs emphasized that they used the first days of the clerkship period to get insight into the student’s expectations, and to learn about what they were able to master on their own. GPs used the analogy of “learning to swim”, arguing that sooner or later students would have to conduct patient consultations on their own.

“In the beginning she just stayed in my office and observed, and then she had to do it by herself, she had to swim, and she was so shocked that she actually had to swim, and she really enjoyed that she could do it. But I was present, I sat there, we switched places, so it was safe.” (GP 3)

Students differed with regards to their expectations and competency, and though some were ready for independent work quickly, others needed a push.

GPs’ approach to support students’ development toward independency

When mutual trust had been established, GPs would encourage students to work independently and to see patients on their own. Students were concerned about how much they were able to do, and they reflected on the transition from being an observer to managing patients, as noted by a student:

“The first week, even though I had my own patients and thought that I did a lot on my own, I now see that in the beginning, she [the teacher] did everything. Just through me. And during my increasing development, I took more and more decisions on my own and had the assurance that I could ask her. And I became more and more confident. And then my teacher took a different role, where she stayed much on her office and answered phone calls instead of entering my office to see all the patients. To me, this was very good supervision.” (Student 3)

Some students reported feeling inexperienced and wanted the supervisor to be available for support and questions, especially for questions regarding practical procedures:

“I don’t think he realizes how little we know when it comes to procedures. We have read and know a lot theoretically and can diagnose and so on. But we know less about minor surgery procedures. But he [the GP] argued that I should be learning by doing, that I had to go for it and do things like cutting and removing cysts without any instruction.” (Student 2)

Although all GPs evaluated the individual student’s level of competency, they varied in how quickly they let students work independently. According to students, there were some GPs who were reluctant to let students do independent work at all.

Some GPs let the students observe them again after they had worked independently for a period, to promote reflections about their experienced approach.

Most GPs had four patients per hour on their schedule, and some deliberately wanted students to learn to work efficiently through what they called “indirect supervision”, to learn to sort patients, and to downscale the scope of the consultation.

Reflections on feedback

Both students and GPs emphasized that feedback had to be constructive to support and encourage the student and point to what the student might do in order to improve. There ought to be concrete suggestions on what to do next time, and further notice taken on whether the student made progress on this topic or not. Teachers emphasized that feedback in the early phase had to rely on observations and close follow-up, be frequent, encouraging, and that corrections had to be given carefully:

“They need lots of praise, and then you see them softening up and become more active.” (GP 4)

GPs underlined that timing was crucial when giving feedback to students. Although some emphasized that it was “now or never”, focusing on giving timely feedback, others could be reluctant to give negative feedback:

“I think I have done this part wrong, because sometimes I just keep it to myself and refrain from saying anything, thinking what’s the point, they’ll be doctors anyway, unless I flunk them, and I seldom want to flunk them.” (GP 3)

GPs said that feedback on technical, non-sensitive topics was easy, but that commenting on behavioral issues such as body language could be difficult. One teacher commented that a student was paying less attention and focusing on electronic devices without giving eye contact. Challenging situations could be students who were very insecure, passive, and reluctant to take action or lacked social or language skills in the consultations:

“She [the student] interfered in my consultations when she should have been observing, and kept talking about herself. It was actually peculiar, things like that can be challenging to stop, when it’s about the student’s personality.” (GP 11)

One GP expressed self-criticism toward that feedback was not given on student behavior, and explained this with lack of teaching experience.

Limited time was reported by students and GPs as an important barrier to good supervision and feedback. Students complained that their teachers were too often busy: “I called him. But I kind of quit doing that. He was always so busy and behind schedule” (Student 1). Some students reported that even if time for supervision and dialogue was possible, the teacher spent time sharing background information about patients, and assessing the student’s work was not given priority.

Views about the StudentPEP tool

GPs had divergent views about using the tool. One group of GPs thought that using StudentPEP was time-consuming, unnecessary, and interfered with giving verbal feedback. Some GPs stated that they made no real effort to give written feedback on the StudentPEP forms, and routinely marked “four” on the five point Likert scale, and wrote “okay” or “not applicable” on all the free text areas, arguing that the questions hardly ever fit the situations. Another group of GPs were more positive, and argued that several aspects of StudentPEP promoted good feedback. They valued the culture learned through the concrete main questions in StudentPEP, and appreciated the arena for reflection that the tool established. One GP shared the experience of being surprised when doing mandatory observation:

“I remember observing one of my students. She was so insecure during a breast examination that I could see that the patient suffered. There was a breast lump and the procedure clearly needed improvement. I wouldn’t have realized this if I were just available for the patient summary and results of the examination. But this time I observed the whole session, and then I could supervise her.”(GP 8)

Students were often very self-critical, and several themes for feedback could emerge from the students’ self-assessment when they commented on their own performance using StudentPEP. Students experienced that patients often gave very positive feedback when they used the tool, and this fostered their confidence. Sometimes patients reported issues that neither the GP nor the student had thought about, which was highly valued:

“Patients mainly give positive feedback, and that makes me confident. Several patients explained what I did well, more than just saying “she did well”, but noted for instance that it was easy to tell what was the problem. But one felt that I didn’t take him seriously. There was a young man worrying about liver cancer, he googled his symptoms and thought he had found the proper diagnose. He was very worried. I didn’t get appraisal there, but it was useful for me.” (Student 1)

Discussion

Principal findings

We found that GPs first supported students’ development in the familiarization phase by exploring the students’ expectations and competency level. When mutual trust had been established through the familiarization phase GPs encouraged students to conduct their own consultations while being available for supervision and feedback. Both students and GPs emphasized that good feedback promoting students’ professional development was timely, constructive, supportive, and focused on ways to improve. Among the challenges that GPs mentioned were giving feedback on behavioral issues such as body language and insensitive use of electronic devices during consultations or if the student was very insecure, passive, and reluctant to take action or lacked social or language skills. Although some GPs experienced StudentPEP as time-consuming and unnecessary, others argued that the tool promoted feedback and learning through mandatory observations and structured questions.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Three of the authors had developed and introduced the mandatory StudentPEP tool. One might expect that participants withheld criticism toward StudentPEP, but both positive and negative views were welcomed, and we found that the tool received both appraisal and criticism in the interviews. Also, one focus group interview with GPs was conducted by the author, J.C.F. who had not been involved in implementing the tool, thereby having a more neutral background. All students and teachers were recruited from the same university, and used the StudentPEP tool during the clerkship period, which might limit the transferability of our findings to other settings. Most of the students were recruited by snowball sampling, which may have led to recruitment of students with similar experiences. However, we think our data displays diversity in views and experiences. We think that findings related to familiarization and the process of building mutual trust might be transferable to other clinical clerkship settings, especially in general practice.

Building a trustful learning environment

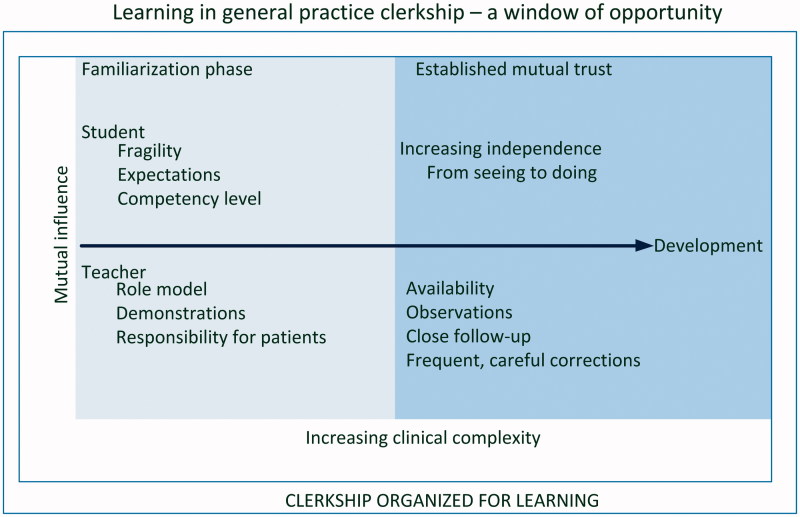

Before the students were allowed to practice on their own, mutual trust had to be established between the teacher and learner. We found that GPs made efforts to make students feel safe in the familiarization phase of the clerkship. Students had to earn their supervisor’s trust. This is confirmed by Bates et al.,[14] who find trusting relationships with preceptors important in longitudinal clerkships. The importance of the relationship between teacher and student, and making the teacher’s approach student-centered was emphasized in a recent Swedish study.[7] However, when the students encountered increasing clinical complexity, mutual trust was being challenged (Figure 1). Complexity calls for further supervision, and mutual trust is built and reinforced when the teacher observes the student with the intention to support the student’s progression. Suggesting a framework for effective supervision in medical education, Kilminster et al. [5] argue that direct supervision, meaning working together and observing each other, and giving constructive feedback are two of the most important features. Archer emphasizes that such feedback must be honest, accurate, and conceptualized as a supported process rather than a series of unrelated events.[3] The building of mutual trust between student and their supervisor is an important process that both student and GP need to be aware of. A trustful learning environment during the clerkship period in general practice depends on continuous investments in the relationship and individualized supervision.

Figure 1.

Learning in general practice clerkship – a window of opportunity.

Dedicated time

Direct observation of the student’s patient encounters by the teacher is considered necessary for good clinical teaching.[15–17] Time and workload were reported as important barriers identified by Larsen and Perkins [18] in a literature review of GP training in general, although the key concern for GPs to take the teacher role is their intrinsic motivation. Positive experiences during the clerkship may motivate students to choose a career in general practice,[19] and the ambition to recruit future colleagues has been described as an important motivation for being a clinical tutor.[7] The high pace of general practice is well known, and our study confirmed that lack of time was a barrier for receiving feedback for some students. However, whereas some did not find time to give feedback, other teachers appeared to spend the time poorly. Cruess et al. [20] encourage teachers to find time, and to seize opportunities to provide feedback. Likewise, Karani discusses the importance of finding teachable moments, i.e. effective use of opportunities to teach.[16] The mindset in “now or never” is, in our opinion, driving the teaching towards reflection-upon-action. However, some of the supervision should be structured with timetabled meetings.[5] Teachers who are busy clinicians should both schedule for teaching as well as seize teachable moments. The faculty should train the teachers to do so, and emphasize the relational aspects to optimize development.

Challenging feedback

We found that GPs easily commented on technical issues, but experienced more sensitive issues such as personal traits, language, or communication skills, as challenging. Boendermaker et al. [21] emphasize that “a good teacher can, wants to, and dares to give good feedback”, indicating that some topics might be a challenge – but necessary – for the teacher to bring up. Gonzalo et al. [22] highlight the “teachable moments” when there is an opportunity to reflect on significant, emotionally charged events. Much emphasis has been placed on giving feedback and the ability to inspire reflection in the trainee.[23] Effective supervision should include both good role modeling and some pastoral care.[5] The process should be informed by a “360 degree perspective”. StudentPEP may promote feedback about challenging issues through the triangulation of feedback, including the self-evaluation items in the instrument. Even though the teachers in our study made use of this tool, all problems with challenging feedback were not solved. This calls for further faculty development and specific training on such feedback. The teacher might make use of specific models for integrated teaching of clinical communication skills when reflecting together with the student around strengths and weaknesses in the consultation, using StudentPEP as a starting point. The Calgary–Cambridge model provides a detailed guide for teaching clinical consultation skills and might be useful for the teacher in this process.[24]

StudentPEP

Even though most patient evaluations were mainly positive, some students experienced that the patient expressed emotions that the student had been unaware of. The StudentPEP tool encouraged reflective discussions between teacher and student, and surprising patient feedback might foster reflections in such discussions. The teachers, however, had different views about the usefulness of a structured tool to facilitate feedback and supervision. Although some GPs were negative to what they regarded as unnecessary faculty interference, others learned through the mandatory observation that they had overestimated the students’ performance level. To re-establish mutual trust, teachers can provide closer clinical supervision aimed at safe and appropriate patient care. External regulations by the institution may be needed to ensure that observation and feedback take place.[5]

Conclusions

Undergraduate clerkships in general practice may be seen as a window of opportunity where students progress from observing the role model to working independently with increasing clinical complexity. Mutual trust is essential to build a learning environment in which supervision and feedback may be given, which highlights the need to spend time on the familiarization phase. StudentPEP may promote feedback and reflection through creating a structured setting for feedback and reflection.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the students and GPs participating in the focus group interviews.

Ethical approval

The participants gave written informed consent to the study. The Norwegian Data Protection Official for Research approved the project (ref. 2010/25820). Approval from the Regional Ethics Committee was not required.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Funding information

A small grant from the university was provided to cover secretary expenses.

References

- 1.Rushforth B, Kirby J, Pearson D. General practice registrars as teachers: a review of the literature. Educ Prim Care. 2010;21:221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuchs S, Klement A, Lichte T, et al. Clerkship in primary care: a cross-sectional study about expectations and experiences of undergraduates in medicine. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2014;31:Doc44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Archer JC. State of the science in health professional education: effective feedback. Med Educ. 2010;44:101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pelgrim EA, Kramer AW, Mokkink HG, et al. The process of feedback in workplace-based assessment: organisation, delivery, continuity. Med Educ. 2012;46:604–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kilminster S, Cottrell D, Grant J, et al. AMEE Guide No. 27: effective educational and clinical supervision. Med Teach. 2007;29:2–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norcini J, Burch V. Workplace-based assessment as an educational tool: AMEE Guide No. 31. Med Teach. 2007;29:855–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Von Below B, Haffling A-C, Brorsson A, et al. Student-centred GP ambassadors: perceptions of experienced clinical tutors in general practice undergraduate training. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015;33:142–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bolter R, Freund T, Ledig T, et al. Video-assisted feedback in general practice internships using German general practitioner's guidelines. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2012;29:Doc68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nilsen S, Baerheim A. Feedback on video recorded consultation in medical teaching: why students loathe and love it – a focusgroup based qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2005;5:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braend AM, Gran SF, Frich JC, et al. Medical students' clinical performance in general practice – Triangulating assessments from patients, teachers and students. Med Teach. 2010;32:333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grol R, Wensing M. Patients evaluate general/family practice: the Europep instrument. Nijmegen: World Organisation of Family Doctors (WONCA)/European Association for Quality in Family Practice; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gran SF, Braend AM, Lindbaek M. Triangulation of written assessments from patients, teachers and students: useful for students and teachers? Med Teach. 2010;32:e552–e558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malterud K. Systematic text condensation: a strategy for qualitative analysis. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40:795–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bates J, Konkin J, Suddards C, et al. Student perceptions of assessment and feedback in longitudinal integrated clerkships. Med Educ. 2013;47:362–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fromme HB, Karani R, Downing SM. Direct observation in medical education: a review of the literature and evidence for validity. Mt Sinai J Med. 2009;76:365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karani R, Fromme HB, Cayea D, et al. How medical students learn from residents in the workplace: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2014;89:490–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutkin G, Wagner E, Harris I, et al. What makes a good clinical teacher in medicine? A review of the literature. Acad Med. 2008;83:452–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larsen K, Perkins D. Training doctors in general practices: a review of the literature. Aust J Rural Health. 2006;14:173–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deutsch T, Lippmann S, Frese T, et al. Who wants to become a general practitioner? Student and curriculum factors associated with choosing a GP career - a multivariable analysis with particular consideration of practice-orientated GP courses. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015;33:47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cruess SR, Cruess RL, Steinert Y. Role modelling - making the most of a powerful teaching strategy. BMJ. 2008;336:718–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boendermaker PM, Schuling J, Meyboom-de Jong BM, et al. What are the characteristics of the competent general practitioner trainer? Fam Pract. 2000;17:547–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalo JD, Heist BS, Duffy BL, et al. Content and timing of feedback and reflection: a multi-center qualitative study of experienced bedside teachers. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boendermaker PM, Conradi MH, Schuling J, et al. Core characteristics of the competent general practice trainer, a Delphi study. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2003;8:111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurtz S, Silverman J, Benson J, et al. Marrying content and process in clinical method teaching: enhancing the Calgary–Cambridge Guides. Acad Med. 2003;78:802–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]