Abstract

Therapeutic endoscopy plays a major role in the management of gastrointestinal (GI) neoplasia. Its indications can be generalized into four broad categories; to remove or obliterate neoplastic lesion, to palliate malignant obstruction, or to treat bleeding. Only endoscopic resection allows complete histological staging of the cancer, which is critical as it allows stratification and refinement for further treatment. Although other endoscopic techniques, such as ablation therapy, may also cure early GI cancer, they can not provide a definitive pathological specimen. Early stage lesions reveal low frequency of lymph node metastasis which allows for less invasive treatments and thereby improving the quality of life when compared to surgery. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) are now accepted worldwide as treatment modalities for early cancers of the GI tract.

Keywords: Superficial gastrointestinal cancers, Endoscopic mucosal resection, Endoscopic submucosal dissection, Lymph node spreading, Esophagus, Stomach, Colorectal

INTRODUCTION

Early gastrointestinal (GI) cancers are defined as lesions limited to the mucosa or submucosa without invading the muscularis propria, regardless of the presence of lymph node metastases. Since 10 years, endoscopic resection is now an alternative to surgery. Surgical resection of early GI cancers offers an excellent (90%-100%) chance of cure based on several series[1,2]. Any major surgical intervention, however, carries risks of complications including wound infection, prolonged hospital stay, anesthetic complications and death. This is especially problematic in elderly patients or those patients with concomitant severe organ dysfunction including heart failure, kidney failure, and lung disease. For this reason, endoscopic therapy may provide an attractive and less invasive treatment option that may ultimately prove to be safer in this select subgroup of patients, and may be able to translate to the general population. These techniques include endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) which are now accepted as treatments for early GI cancers in selected cases.

Therapeutic endoscopy plays a major role in the management of GI neoplasia. Its indications can be generalized into four broad categories; (1) to remove neoplastic lesion; (2) to obliterate neoplastic lesion; (3) to palliate malignant obstruction; (4) to treat bleeding. Only endoscopic resection allows complete histological staging of the cancer, which is critical as it allows stratification and refinement for further treatment. Although other endoscopic techniques, such as ablation therapy, may also cure early GI cancer, they can not provide a definitive pathological specimen.

Early stage lesions reveal low frequency of lymph node metastasis which allows for less invasive treatments and thereby improving the quality of life when compared to surgery[3]. EMR and ESD are now accepted worldwide as treatment modalities for early cancers of the GI tract[3-5].

Early GI cancers (except the esophagus) are defined as being limited to the mucosa or submucosa, but not invading the muscularis propria, regardless of the presence of lymph node metastases. A macroscopic classification of these lesions was first established by Japanese endoscopists in 2002 (Table 1) and has now been accepted worldwide[5].

Table 1.

Japanese classification of GI cancers

| Classification of GI cancers | |

| Type 0 | Superficial, flat with minimal elevation/depression |

| Type 0-I: Protruding type | |

| Type 0-IIa: Superficial elevated type | |

| Type 0-IIb: Flat type | |

| Type 0-IIc: Superficial depressed type | |

| Type 0-III: Excavated type | |

| Type 1 | Polypoid tumors on wide base, distinct demarcation from surrounding mucosa |

| Type 2 | Ulcerated with sharply demarcated and raised borders |

| Type 3 | Ulcerated without definite margins, infiltrating into adjacent wall |

| Type 4 | Diffusely infiltrating lesion without marked ulceration |

| Type 5 | Non classifiable into any of above types |

Detection and diagnosis of early GI cancer can be difficult because of the less well defined subtle findings. Chromoendoscopy is an important adjunct technique to enhance visualization of superficial early cancers and to define their borders. Indigo carmine solution (0.2%), a contrast dye, is commonly used in the stomach to highlight the contours and topography of the lesion by entering mucosal depressions and crevices, thus enabling the biopsy of the minute lesions. Recently, narrow band image (NBI) and autofluorescence images (AFIs) are introduced as a virtual chromoendoscopy.

The depth of invasion is measured microscopically and the risk of lymph node metastasis is known to be related with a defined micrometric cutoff. In squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the esophagus, when infiltration is less than 200 μm, the risk of nodal metastases is low[6] For early adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus (BE) and early gastric cancer (EGC), a submucosal infiltration micrometric cutoff of 500 μm has been proposed, as the risk of nodal metastases appears low[7]. In contrast, a 20%-25% risk of node involvement with submucosal infiltration in Barrett's cancer has been reported in the West. In the colorectum, the risk of lymph node metastasis is negligible when the tumor invasion is less than 1000 μm[8].

EMR TECHNIQUES

Several different EMR techniques have been described, the most common of which are detailed below.

Strip biopsy

Strip biopsy requires the use of a two-channel endoscope. The lesion is lifted with submucosal injection in the standard fashion. A snare and forceps are introduced through each channel of the endoscope. The forceps are used to guide the lesion in to the snare, which is then closed around the base of the lesion and resected using standard electrocautery[1].

Endoscopic double snare polypectomy

A double-channeled endoscope is required for this procedure. Snares are introduced through both channels of the endoscope, one passing through the open loop of the other. The lesion is lifted and strangulated with the first snare, and resected below with the second snare[9].

EMR using cap fitted endoscope

A transparent cap with a prelooped snare on its distal tip is placed on the end of an endoscope. The lesion is lifted with a submucosal injection in standard fashion. Suction is then used to draw the lesion into the cap, and the snare is closed on the base. It is then released from the cap by breaking suction, and then removed similarly to any polypoid lesion[10].

EMR: Ligation device

A standard variceal ligation device is placed on the tip of the endoscope. The lesion may be injected submucosally for lifting. The lesion is then suctioned into the ligation device and a rubber band is deployed. A snare is then used to resect the lesion, usually below the level of the rubber band[11].

ESD

ESD is a relatively new technique that has been used to resect larger (greater than 20 mm) size mucosal lesions in the stomach. The target lesion is first marked after careful examination with coagulation current from the tip of a knife approximately 5 mm around the margins of the tumor. The entire marked area is then elevated with a sub-mucosal injection. A needle knife is then used to cut along the outside of the margins, while the lesion is still elevated. Dissection along the submucosal plane is then performed using tools such as a hook knife or flex knife[12-14]. This technique takes significantly longer to perform than traditional EMR techniques, and requires the endoscopist to be experienced with these various tools. Larger studies are needed to assess the viability and complete resection rates with submucosal dissection.

RESULTS OF ENDOSCOPIC RESECTION

SCC of the esophagus

Multiple synchronous lesions as well as metachronous lesions have been reported up to 31% of patients with esophageal SCC[15]. Five-year survival rate is up to 95% after EMR in patients with superficial SCC without lymph node metastasis in m1 and m2 SCC of the esophagus[16]. Recently, an expanded indication for EMR in patients with superficial esophageal carcinoma m3 or sm1 has been proposed[17]. A study from Germany consisting of 12 HGD and 53 mucosal SCC of the esophagus, reported on the treatment using a ligation EMR technique[17]. This was the first Western study which showed similar results to those of the Japan in early esophageal SCC. They reported that complete resection was achieved in 11/12 patients of HGD and 51/53 patients of mucosal SCC. Although recurrence was observed in 16 patients after EMR, the lesions were completely resected after further endoscopic treatment. Complications occurred in 15/65 patients all being esophageal strictures which were successfully managed by endoscopy. Seven year survival rate was 77%.

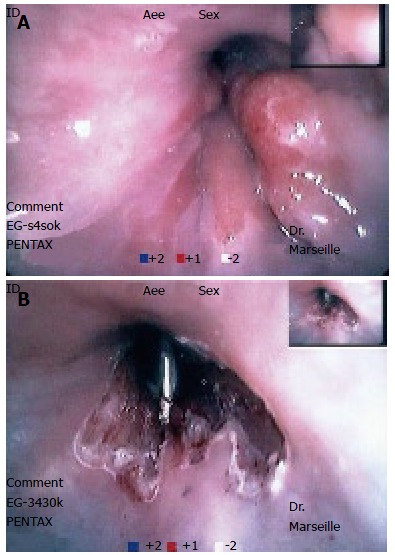

High grade dysplasia and early carcinoma developed in BE

Endoscopic therapy aims to remove the dysplastic Barrett's epithelium allowing restoration of squamous epithelium. EMR could be a therapeutic alternative to surgical esophagectomy which carries substantial morbidity and mortality[18]. When HGD is diagnosed in short segment BE (BE shorter than 30 mm in length), EMR would be considered to remove all the metaplastic epithelium. A study reported that visible areas of HGD in long segment BE (BE longer than 30 mm in length) may be removed by EMR, followed by photodynamic therapy to destroy invisible foci[19]. Although strictures occurred in 30% of patients, 17 superficial esophageal cancers were removed by combining EMR and photodynamic therapy. A study from Germany reported that circumferential EMR was carried out by using a simple snare technique without a cap in 12 patients with BE containing multifocal high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia or intramucosal cancer[20]. Five had multifocal lesions while two developed strictures that required bougienage. There was no recurrence during the median follow-up of 9 mo. Our study reported on circumferential EMR (Figure 1) performed in 21 patients with HGD or mucosal cancer[21]. Three patients needed additional therapy such as surgery or chemotherapy due to residual disease after the endoscopic resection. In addition, two local recurrences were retreated by EMR. A study from Netherlands, consisting of 77 esophagectomy specimens containing HGD or T1 adenocarcinoma, reported that lymph node metastasis occurred in 23% sm2 and 69% sm3 tumors, but not in m1, m2, m3, and sm1 lesions[22]. They concluded that m1, m2, m3, and sm1 lesions could be treated endoscopically if the lesions are less than 30 mm, well differentiate type adenocarcinoma, and without lymphangitic invasion. However, care must be taken with the initial diagnosis of endoscopic biopsy since significant changes in diagnosis occur after EMR such as downgrading from HGD to BE without dysplasia or being reclassified from benign to malignant diagnosis[23]. Ell et al reported that suck-and-cut EMR technique was performed in 100 consecutive patients with low-risk adenocarcinoma of the esophagus arising from BE, and complete local remission was achieved in 99/100 patients[24]. During the mean follow-up period of 36.7 mo, recurrent or metachronous carcinomas were found in 11% of the patients, but were successfully treated by repeated EMR. Five-year survival rate was 98%.

Figure 1.

Circumferential endoscopic resection of BE with high grade dysplasia. A: Polypoid tumor on BE; B: Post-resection endoscopic aspects.

Recently, a study tried to define prognostic factors of recurrence after Endoscopic Resection of early carcinoma in BE. The aim of this study was to evaluate the value of p53 and Ki-67 immunohistochemistry in predicting the cancer recurrence in patients with Barrett’s esophagus-related cancer referred to EMR. Mucosectomy specimens from 41 patients were analyzed. All endoscopic biopsies prior to EMR presented high-grade dysplasia and cancer was detected in 23 of them. Ki-67 and p53 immunoreactivity were classified as superficial, deep or mixed. EMR samples confirmed cancer in 21/23 (91.3%) cases. In these cases, p53 immunohistochemistry revealed a mixed positivity for the great majority of these cancers (90.5% vs 20%; P < 0.001), and Ki-67 showed a mixed pattern for all cases (100% vs 30%; P < 0.001); on the contrary, patients without cancer revealed a superficial or negative pattern for p53 (80% vs 9.5%; P < 0.001) and Ki-67 (70% vs 0%; P < 0.001). During a mean follow-up of 31.6 mo, 5 (12.2%) patients developed six episodes of recurrent or metachronous cancer. Previous EMR samples did not show any significant difference in the p53 and Ki-67 expression for patients developing cancer after endoscopic treatment[25].

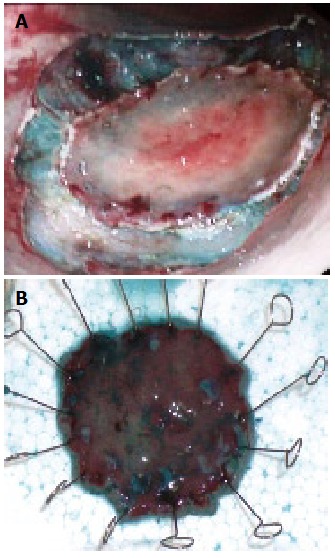

Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer

Complete resection rates (defined as tumor free horizontal and vertical margins, submucosal invasion < 500 μm, and no lymphatic invasion) have been reported to be between 74% and 97% with the use of EMR, with lower rates of complete resection reported when expanded indications for EMR were used and when lesions were resected piecemeal instead of en bloc (Figure 2)[25-27]. Although no head to head prospective trials have been performed looking at long-term survival for EMR versus surgery, 2 and 5-year survival rates for EMR are 95% and 100%, respectively, whereas they are 100% and 100% for patients who underwent surgery[27]. Similarly, other investigators have shown no differences in survival rates after 5 and 10-year periods for EMR compared with surgery[28].

Figure 2.

ESD of early gastric cancer. A: Peripherial dissection of superficial gastric cancer; B: Resected specimen.

No cases of mortality due to EMR have been reported in various case series. The most serious complications of EMR include bleeding and perforation. Reported rates of bleeding vary from 1% to 20% and appear to be more frequent when resecting large lesions and when resecting lesions piecemeal[29,30]. One study reported surgical postoperative complications of 14.7% and a 0.7% mortality rate[31]. Recurrence rates in a recent study published by Ono et al[32] were noted to be 2% in those who had complete resection (5 of 278 cases) while there was a 13% recurrence rate in the group of patients whose resection could not be deemed complete histologically (9 of 67 cases). Local recurrences for incomplete resections in the same study are reported to be approximately 37%[32]. It should be noted that a global advantage of surgical resection is a near complete cure for early gastric cancers.

Only one study has addressed the issue of quality of life, and EMR appears to have a better post procedure quality of life compared with surgical gastrectomy[33]. No cost benefit analyses have been performed. Surgical intervention may have a high initial cost burden, however repeat surveillance endoscopies may add up to a significant cost as well.

Endoscopic resection of duodenal tumors

EMR has been used for ampullary and peri-ampullary neoplasias and sub-epithelial lesions including stromal cell tumors, cysts, and neuroendocrine tumors. Although endoscopic resection can provide a wide tumor resection with a negative resection margin, it is not yet recommended as a curative therapy for early stage ampulla of Vater cancer because of the high lymphovascular invasion rate[34]. A study reported a higher risk of bleeding (33%) among 27 duodenal EMR after complete resection[35].

Endoscopic resection of submucosal tumors

EMR technique may also be applied to submucosal tumors in order to achieve histologic diagnosis and to achieve complete removal. In a German study, complete resection was achieved in 19/20 patients with submucosal esophageal tumors using a rubber band or a simple snare[36,37]. Bleeding occurred in 40% of the cases and was successfully managed by endoscopic hemostasis. Rosch et al attempted endoscopic en bloc resection of mucosal and submucosal tumors of the UGI tract, using the IT knife[38]. In this pilot series, complete removal was achieved in 25% of the mucosal and 36% of the submucosal lesions of 37 lesions; 13 in esophagus, 24 in stomach and 1 in duodenum. Perforation occurred in one case, and was managed conservatively with endoscopic clipping.

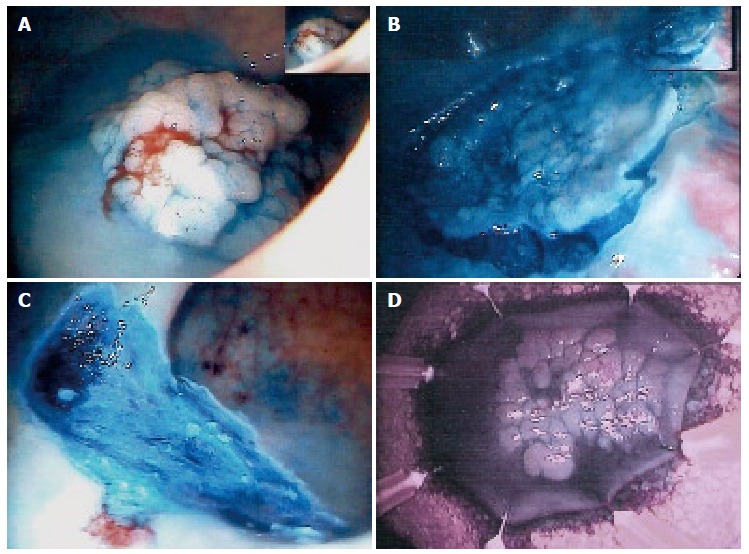

Endoscopic resection of colorectal tumors

EMR and ESD are being successfully used for early stage colon cancers, flat adenomas, large superficial colorectal tumors, and rectal carcinoids[39]. Lymph node metastasis in T1 colorectal carcinoma occurs only after infiltrating submucosa and is correlated to the depth of submucosal penetration by the tumor[40]. This supports the therapeutic effectiveness of endoscopic removal of polyps and flat lesions that are confined to the mucosa, regardless of their size. On the other hand, colorectal laterally spreading tumor (LST) classified as granular (LST-G) and non granular type (LST-NG), are defined as lesions larger than 10 mm in diameter, with a low vertical axis, extending along the luminal wall[41]. For en bloc resection of flat lesions larger than 20 mm, conventional EMR is inadequate because of incomplete removal and frequent local recurrence. When analyzing the endoscopic features of 257 LSTs in order to assess which features correlated with the depth of invasion, unevenness of nodules, presence of large nodules, size, histological type, and presence of depression in the tumor were significantly associated with the depth of invasion[41]. In addition, LST-NG showed a higher frequency of sm invasion than LST-G (14% vs 7%)[42]. Presence of a large nodule in LST-G type was associated with higher sm invasion while pit pattern, sclerous wall change, and larger size were significantly associated with higher sm invasion in LST-NG type. Therefore, it is advisable to perform endoscopic piecemeal resection for LST-G type with the area including the large nodule resected first. Besides, LST-NG type should be removed by en bloc resection (Figure 3) because of the higher potential of sm invasion when compared to that of the LST-G type[42].

Figure 3.

ESD of a flat villous rectal polyp with sm1 carcinoma. A: Flat villous, adenoma of the sigmoid colon; B: Peripherical dissection; C: Resected area; D: Resected specimen.

A study from Germany reported that complications occurred in two patients of 57 patients after EMR in large colorectal neoplasia between 10 mm and 50 mm[43]. Recurrence rate following EMR ranges from 0% to 40% which could be reduced when combined by argon plasma coagulation. However, a recent study from Poland revealed that argon plasma coagulation did not reduce the recurrence rate compared to polypectomy alone[44]. Besides, another study reported that EMR was performed for 139 SP in 136 patients by snare polypectomy, and invasive carcinoma was found in 17 cases[45]. After 12 mo of follow up after EMR, no local recurrence was detected in 7 patients with invasive carcinoma without surgery. Another study from UK reported on 30 large colorectal polyps which were treated by en bloc resection in 22 cases and by piecemeal resection in 8 cases[45]. Histologically, the lesions were predominantly adenomatous polyps, but 7 cases revealed incidental focus of adenocarcinoma. Although bleeding occurred in 2 cases, there was no bowel perforation. There was no evidence of recurrence during the median follow-up of 21 mo.

In a prospective cohort study in Italy, IT knife was used for EMR of large colorectal polyps larger than 3 cm which are unsuitable for standard polypectomy[46]. The results showed the likelihood of complete en bloc resection of mucosal lesions improved by new approach with IT knife when compared with previous studies on colonic EMR, even for lesions located in difficult positions or larger than 30 mm. En bloc resection was achieved only in 55.1% of the lesions and piecemeal resection was performed in the rest of the cases. Although complete tumor removal was achieved in 19 patients, 13 had LGD, 15 had HGD, and one had a tumor invading the submucosa. Complications occurred in four patients which were all managed conservatively. Local recurrences were detected in five patients and were treated by argon plasma coagulation and snare polypectomy. There was no recurrence during the median follow-up period of 15.7 mo[47].

CONCLUSION

EMR and ESD techniques should be considered as elective treatment modality for early GI cancers as long as it is performed under the right indications by an expertise.

Footnotes

S- Editor Li DL L- Editor Rippe RA E- Editor Zhang WB

Peer reviewer: Mitsuhiro Fujishiro, PhD, Department of Gastroenterology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan

References

- 1.Matsukuma A, Furusawa M, Tomoda H, Seo Y. A clinicopathological study of asymptomatic gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:1647–1650. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das A, Singh V, Fleischer DE, Sharma VK. A comparison of endoscopic treatment and surgery in early esophageal cancer: an analysis of surveillance epidemiology and end results data. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1340–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conio M, Ponchon T, Blanchi S, Filiberti R. Endoscopic mucosal resection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:653–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rembacken BJ, Gotoda T, Fujii T, Axon AT. Endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2001;33:709–718. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-16224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soetikno RM, Gotoda T, Nakanishi Y, Soehendra N. Endoscopic mucosal resection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:567–579. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nozoe T, Saeki H, Ohga T, Sugimachi K. Clinicopathologic characteristics of superficial spreading type squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Oncol Rep. 2002;9:313–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kashimura H, Ajioka Y, Watanabe H, Nishikura K, Iiri T, Asakura H. Risk factors for nodal micrometastasis of submucosal gastric carcinoma: assessment of indications for endoscopic treatment. Gastric Cancer. 1999;2:33–39. doi: 10.1007/s101200050018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamada S, Ajioka Y, Watanabe H, Hashidate H, Takaku H, Kazama S, Yokoyama J, Nishikura K, Fujiwara T, Asakura H. Heterogeneity of p53 mutational status in intramucosal carcinoma of the colorectum. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2001;92:161–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2001.tb01078.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopes CV, Hela M, Pesenti C, Bories E, Caillol F, Monges G, Giovannini M. Circumferential endoscopic resection of Barrett's esophagus with high-grade dysplasia or early adenocarcinoma. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:820–824. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inoue H, Sato Y, Sugaya S, Inui M, Odaka N, Satodate H, Kudo SE. Endoscopic mucosal resection for early-stage gastrointestinal cancers. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:871–887. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seewald S, Ang TL, Omar S, Groth S, Dy F, Zhong Y, Seitz U, Thonke F, Yekebas E, Izbicki J, et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection of early esophageal squamous cell cancer using the Duette mucosectomy kit. Endoscopy. 2006;38:1029–1031. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oyama T, Tomori A, Hotta K, Morita S, Kominato K, Tanaka M, Miyata Y. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early esophageal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:S67–S70. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yahagi N, Fujishiro M, Kakushima N, Kobayashi K, Hashimoto T, Oka M, Iguchi M, Enomoto S, Ichinose M, Niwa H, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer using the tip of an electrosurgical snare (thin type) Dig Endosc. 2004;16:34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamoto H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early cancers and large flat adenomas. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:S74–S76. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Japanese Society for Esophageal Disease. Guidelines for the clinical and pathologic studies for carcinoma of the esophagus. Jpn J Surg. 1976;6:79–86. doi: 10.1007/BF02468890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higuchi K, Tanabe S, Koizumi W, Sasaki T, Nakatani K, Saigenji K, Kobayashi N, Mitomi H. Expansion of the indications for endoscopic mucosal resection in patients with superficial esophageal carcinoma. Endoscopy. 2007;39:36–40. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-945148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pech O, May A, Gossner L, Rabenstein T, Manner H, Huijsmans J, Vieth M, Stolte M, Berres M, Ell C. Curative endoscopic therapy in patients with early esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma or high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. Endoscopy. 2007;39:30–35. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-945040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.May A, Gossner L, Pech O, Fritz A, Gunter E, Mayer G, Muller H, Seitz G, Vieth M, Stolte M, et al. Local endoscopic therapy for intraepithelial high-grade neoplasia and early adenocarcinoma in Barrett's oesophagus: acute-phase and intermediate results of a new treatment approach. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:1085–1091. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200210000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buttar NS, Wang KK, Lutzke LS, Krishnadath KK, Anderson MA. Combined endoscopic mucosal resection and photodynamic therapy for esophageal neoplasia within Barrett's esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:682–688. doi: 10.1067/gien.2001.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seewald S, Akaraviputh T, Seitz U, Brand B, Groth S, Mendoza G, He X, Thonke F, Stolte M, Schroeder S, et al. Circumferential EMR and complete removal of Barrett's epithelium: a new approach to management of Barrett's esophagus containing high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia and intramucosal carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:854–859. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)70020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giovannini M, Bories E, Pesenti C, Moutardier V, Monges G, Danisi C, Lelong B, Delpero JR. Circumferential endoscopic mucosal resection in Barrett's esophagus with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia or mucosal cancer. Preliminary results in 21 patients. Endoscopy. 2004;36:782–787. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-825813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buskens CJ, Westerterp M, Lagarde SM, Bergman JJ, ten Kate FJ, van Lanschot JJ. Prediction of appropriateness of local endoscopic treatment for high-grade dysplasia and early adenocarcinoma by EUS and histopathologic features. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:703–710. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nijhawan PK, Wang KK. Endoscopic mucosal resection for lesions with endoscopic features suggestive of malignancy and high-grade dysplasia within Barrett's esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:328–332. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.105777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ell C, May A, Pech O, Gossner L, Guenter E, Behrens A, Nachbar L, Huijsmans J, Vieth M, Stolte M. Curative endoscopic resection of early esophageal adenocarcinomas (Barrett's cancer) Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopes CV, Mnif H, Pesenti C, Bories E, Monges G, Giovannini M. p53 and Ki-67 in Barrett's carcinoma: is there any value to predict recurrence after circumferential endoscopic mucosal resection? Arq Gastroenterol. 2007;44:304–308. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032007000400005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kakushima N, Fujishiro M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastrointestinal neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2962–2967. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimura T, Joh T, Sasaki M, Kataoka H, Tanida S, Ogasawara N, Yamada T, Kubota E, Wada T, Inukai M, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection is useful and safe for intramucosal gastric neoplasms in the elderly. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2007;70:323–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanaka M, Ono H, Hasuike N, Takizawa K. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. Digestion. 2008;77 Suppl 1:23–28. doi: 10.1159/000111484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee IL, Wu CS, Tung SY, Lin PY, Shen CH, Wei KL, Chang TS. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancers: experience from a new endoscopic center in Taiwan. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:42–47. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000225696.54498.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Min BH, Lee JH, Kim JJ, Shim SG, Chang DK, Kim YH, Rhee PL, Kim KM, Park CK, Rhee JC. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for treating early gastric cancer: Comparison with endoscopic mucosal resection after circumferential precutting (EMR-P) Dig Liver Dis. 2008:In Press. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujishiro M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric cancer. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2008;11:119–124. doi: 10.1007/s11938-008-0024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ono H, Hasuike N, Inui T, Takizawa K, Ikehara H, Yamaguchi Y, Otake Y, Matsubayashi H. Usefulness of a novel electrosurgical knife, the insulation-tipped diathermic knife-2, for endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2008;11:47–52. doi: 10.1007/s10120-008-0452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohyama T, Kobayashi Y, Mori K, Kano K, Sakurai Y, Sato Y. Factors affecting complete resection of gastric tumors by the endoscopic mucosal resection procedure. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:844–848. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dittrick GW, Mallat DB, Lamont JP. Management of ampullary lesions. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2006;9:371–376. doi: 10.1007/BF02738525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oka S, Tanaka S, Nagata S, Hiyama T, Ito M, Kitadai Y, Yoshihara M, Haruma K, Chayama K. Clinicopathologic features and endoscopic resection of early primary nonampullary duodenal carcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;37:381–386. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200311000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park YS, Park SW, Kim TI, Song SY, Choi EH, Chung JB, Kang JK. Endoscopic enucleation of upper-GI submucosal tumors by using an insulated-tip electrosurgical knife. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:409–415. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02717-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun S, Ge N, Wang C, Wang M, Lu Q. Endoscopic band ligation of small gastric stromal tumors and follow-up by endoscopic ultrasonography. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:574–578. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosch T, Sarbia M, Schumacher B, Deinert K, Frimberger E, Toermer T, Stolte M, Neuhaus H. Attempted endoscopic en bloc resection of mucosal and submucosal tumors using insulated-tip knives: a pilot series. Endoscopy. 2004;36:788–801. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-825838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saito Y, Uraoka T, Matsuda T, Emura F, Ikehara H, Mashimo Y, Kikuchi T, Fu KI, Sano Y, Saito D. Endoscopic treatment of large superficial colorectal tumors: a case series of 200 endoscopic submucosal dissections (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:966–973. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamamoto S, Watanabe M, Hasegawa H, Baba H, Yoshinare K, Shiraishi J, Kitajima M. The risk of lymph node metastasis in T1 colorectal carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:998–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saito Y, Fujii T, Kondo H, Mukai H, Yokota T, Kozu T, Saito D. Endoscopic treatment for laterally spreading tumors in the colon. Endoscopy. 2001;33:682–686. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-16213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uraoka T, Saito Y, Matsuda T, Ikehara H, Gotoda T, Saito D, Fujii T. Endoscopic indications for endoscopic mucosal resection of laterally spreading tumours in the colorectum. Gut. 2006;55:1592–1597. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.087452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jameel JK, Pillinger SH, Moncur P, Tsai HH, Duthie GS. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) in the management of large colo-rectal polyps. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:497–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaltenbach T, Friedland S, Maheshwari A, Ouyang D, Rouse RV, Wren S, Soetikno R. Short- and long-term outcomes of standardized EMR of nonpolypoid (flat and depressed) colorectal lesions > or = 1 cm (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:857–865. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hurlstone DP, Fu KI, Brown SR, Thomson M, Atkinson R, Tiffin N, Cross SS. EMR using dextrose solution versus sodium hyaluronate for colorectal Paris type I and 0-II lesions: a randomized endoscopist-blinded study. Endoscopy. 2008;40:110–114. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Repici A, Conio M, De Angelis C, Sapino A, Malesci A, Arezzo A, Hervoso C, Pellicano R, Comunale S, Rizzetto M. Insulated-tip knife endoscopic mucosal resection of large colorectal polyps unsuitable for standard polypectomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1617–1623. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Repici A. From EMR to ESD: a new challenge from Japanese endoscopists. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:572–574. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]