Abstract

Background:

Recent developments in pain rehabilitation emphasise the importance of promoting psychological flexibility. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is one approach that has been shown to be effective for the treatment of chronic musculoskeletal pain. However, studies have shown that introducing innovative approaches such as ACT into established health care can cause some anxiety for professional groups. We used Action Research to evaluate the implementation of ACT to a physiotherapy-led pain rehabilitation programme.

Methods:

All staff in the pain service were invited to participate. Participants took part in focus groups, engaged in reflective sessions/meetings and completed reflective diaries. The analysis was undertaken by an experienced qualitative researcher using constant comparison. Participants reviewed emerging themes and validated the findings.

Results:

Four key themes emerged from the study: (a) the need to see pain as an embodied, rather than dualistic, experience; (b) the need for a more therapeutic construction of ‘acceptance’; (c) value-based goals as profound motivation for positive change; and (d) it’s quite a long way from physiotherapy. Integral to a therapeutic definition of acceptance was the challenge of moving away from ‘fixing’ towards ‘sitting with’. Participants described this as uncomfortable because it did not fit their biomedical training.

Conclusion:

This article describes how Action Research methodology was used in the introduction of ACT to a physiotherapy-led pain rehabilitation programme. The innovation of this study is that it helps us to understand the potential barriers and facilitators to embedding an ACT philosophy within a physiotherapy setting.

Keywords: Action Research, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Physiotherapy, Pain rehabilitation, Pain management, Chronic pain, Pain Clinics

Background

Traditionally, pain rehabilitation programmes have been based on a cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) approach.1 In the last few years, there has been a trend to move away from traditional CBT approaches and increased uptake of more contextualised psychological therapies such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and mindfulness.2 ACT is one approach that appears to be effective for the treatment of chronic pain.3–7 ACT is a third-wave CBT which promotes psychological flexibility and uses mindfulness among other elements. To date, the reports on effectiveness of ACT have been from programmes that predominantly rely on the delivery of ACT by clinical psychologists.3,6,7

While many trials and systematic reviews have established that multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation programmes are effective for patients with chronic low back pain, many UK hospitals struggle to provide such programmes due to the high cost and difficulties in accessing clinical psychologists working in chronic pain.8,9 The training of physiotherapists now encompasses behavioural and psychological treatment techniques, and many programmes are run by physiotherapists based upon cognitive behavioural principles. There is moderate to high-quality evidence of small effects for physiotherapy-led functional restoration programmes.9

The implementation of a move towards an ACT-based approach to pain rehabilitation from the more traditionally utilised CBT approaches has been described by Trompetter et al.10 Although the physiotherapists in the team were not ACT therapists, it was necessary for them to develop the therapeutic stance of ACT. Competencies of an ACT therapist include demonstration of equality, vulnerability, compassion, a sharing point of view, ability to be flexible to suit the needs of the group and where appropriate to self-disclose as well as accept challenging content.11 This requires particular clinical skills and has the potential to feel uncomfortable for the clinician. Indeed, a qualitative study of staff from a number of different clinical backgrounds about their experiences of changing to ACT found that uncertainty and discomfort were an emergent theme.12

The objective of our study was to implement and evaluate a programme of development introducing ACT into a physiotherapy-led chronic pain rehabilitation programme using Action Research.

Methods

The project received full ethical approval from the Oxford University Medical Sciences Division Research Ethics Committee (Ref MSD-IDREC-C1-2013-137). We followed the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) conceptual framework13 to implement ACT as this methodology focuses on generating solutions to practical problems and has the ability to empower practitioners by engaging them in the research process and implementation activities.14–16 Specifically, we used Emancipatory Action Research which places the members of the clinical team as research participants through a process of systematic reflection and critique.17,18 The project took place over a 1-year period with a team of physiotherapists providing a chronic pain rehabilitation service within a specialist musculoskeletal hospital setting. The clinical lead of the service was supported through the study in a facilitatory model of critical companionship.19 The aim of this model is to accompany the experiential learning journey and to support change through constructive critique, analysis and evaluation of practice. The team undertook training, planned the introduction of ACT to the clinical programmes and completed reflective diaries and recorded discussions at team meetings. A qualitative researcher (FT) was embedded in the team to collaborate on the project, to assist with evaluating changes, to provide an additional perspective on the process of critical reflection and to collect individual interview data.

The physiotherapists working within the pain rehabilitation programme had varied experience, but all had undergone extensive post-qualification training in psychological therapeutic techniques such as CBT, mindfulness and motivational interviewing and were currently familiar with working within a CBT-based pain management approach. The team were given further training and mentoring in ACT from acknowledged expert practitioners, with exposure to core principles, opportunity to practice and role-play techniques and through experiential learning. We sought to engage as many of the physiotherapists as possible, but we also reassured staff that they did not need to participate if they did not wish to. All but one agreed to participate. In total, seven staff participated: one clinical lead; three advanced physiotherapy practitioners, two senior physiotherapists and an assistant practitioner:

there was a range of opinions about the usefulness of ACT within the team and some did not feel that ACT was necessarily superior to other approaches that they had been using. The independent qualitative researcher was not familiar with ACT prior to the study.

Data collection

Following the key principle of co-operative inquiry, staff took part in focus groups, engaged in reflective sessions and completed reflective diaries. They attended ad hoc reflective sessions and team meetings to jointly discuss the progress that was being made and to co-design further changes or to share their insights into successes and setbacks. Interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim. Staff provided F.T. with their transcripts of reflexive diaries.

Analysis

Transcribed data were uploaded into NVivo 9 Software for qualitative analysis using coding and sorting data into categories with shared meaning, in order to provide a conceptual structure that makes sense of the data, using a process of constant comparison.20 To maximise the essence of Action Research as participatory research, themes were presented to the team for discussion. To address the objectives of the study and to increase the rigour and completeness of the data and project outcome, affirmation and evaluation of data were achieved by field notes, completion of individual reflective diaries, recording written minutes of team reflections and completing individual semi-structured interviews with clinical participants conducted by an independent researcher.

Results

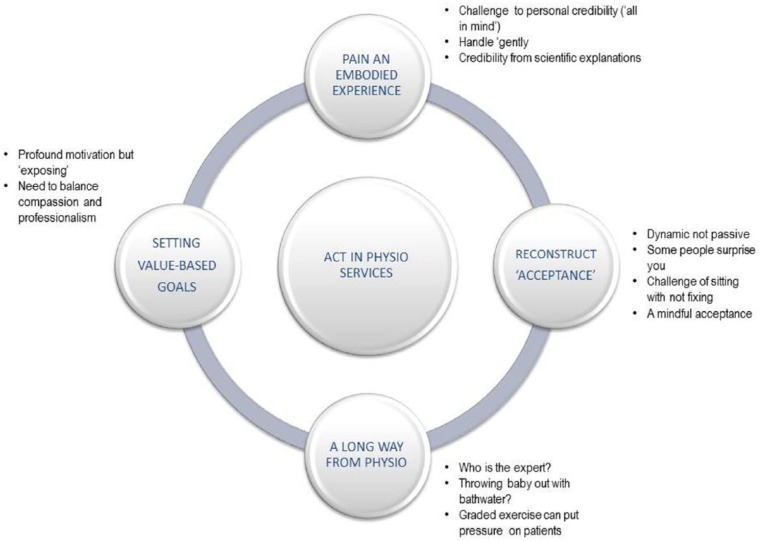

Four main themes were found, which describe potential barriers and facilitators to the use of an ACT philosophy within a physiotherapy-led pain management service (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Barriers and facilitators.

Understanding pain as an embodied experience

Participants explored the need to understand the experience of pain as an embodied experience, rather than a dualistic experience of body and mind. For example, patients would be encouraged to reflect on the how their thoughts and emotions could affect their experience of pain:

I think what the programme does is enables people to start to hold everything up and understand the effect of all those emotions on their pain … in a very gentle way.

Participants explored the need to validate a person’s experience and to assure them that you believe them:

I think it’s so important for the person to feel believed, that they don’t have to keep trying to persuade you that they have got pain. But they also recognise that other things will affect the treatment.

I am in agony I am in pain and yet they tell me they can’t find anything wrong … that comes with a huge frustration and people are like well there must be something wrong because I am in pain

One strategy for validating experience discussed was providing a ‘scientific’ explanation for pain. This could meet the requirements of a medical model and confirm a person’s credibility. However, an ACT approach does not advocate teaching scientific explanations for pain, but rather focuses on moving forward from today. Therefore, participants described uncertainty about whether or not to give a scientific explanation:

Training that I received about ACT basically says pain education isn’t part of an ACT programme … and I have said the difficulty I have around it is for some people it seems to be useful to have a greater understanding of their pain, but not always.

In some ways I think for some people it validates their experience and that is why I think it could be useful … I guess we need to be brave and just take that leap to just take it out completely if we are just going to do that.

Reconstructing ‘acceptance’

The physiotherapists described a tension in the use of the term ‘acceptance’. It was felt to have connotations of giving up and passivity rather than fostering a positive and proactive approach to therapy:

Acceptance almost seems to be a bit defeatist that you just have to give into it whereas it is not that at all … I think patients think they have just got to get on with it … but that is not what [acceptance] really means therapeutically. I guess it means embracing the experience of pain and still being able to do the things that they want to do but with their pain.

Therapeutically, the physiotherapists constructed ‘acceptance’ as a dynamic (not passive) and challenging (not defeatist) process. They also recognised that a person’s capacity to ‘accept’ was dynamic and contextual, that is, it could waiver depending on personal circumstances:

We are saying it’s not a passive process and it’s not giving up, it could actually be a very brave process if it’s taking you towards some really difficult emotions.

Integral to a therapeutic definition of acceptance was the professional challenge of moving away from diagnosis and ‘fixing’ towards ‘sitting with’ patients. Participants described this as uncomfortable because they sometimes felt that they had failed in their professional role. This was something that got easier with practise or experience, but even for those with more experience, it remained uncomfortable at times:

You can sit with the distress without having to resolve it right there, it is about approaching these really uncomfortable things … actually that is part of ACT its uncomfortable for us as well as for the patients because we can’t necessarily resolve it.

If you are trying to get [someone] better in terms of pain control, and that is not possible, you feel like you have failed in your work … Whereas in a pain management … they know straight away the expectation is not necessarily to eradicate pain but to improve mood and function and quality of life and, so it’s more fulfilling because those goals are more likely to be achieved.

Despite the challenge of sitting with, the benefits were described as being more ‘peaceful’ for both patient and therapist. For example, not being able to fix someone could be very demoralising for a therapist and leave them with a sense of having failed:

It really helps with how robust you feel as a clinician as again you are not feeling to this point that you are somehow failing somebody and you are helping them feel a bit more peaceful about their situation rather than trying to constantly resolve something that might not be possible to do.

Participants explored the place of mindfulness in a more compassionate construction of acceptance. Mindfulness is integral to an ACT philosophy and involves a neutral, rather than worried, method for observing bodily experience and associated thoughts. Participants described mindfulness as a kinder way to approach the experience of chronic pain. It does not aim to identify, challenge and eradicate ‘unhelpful thoughts’ but focuses on stepping back from the thoughts, without judgement, and accepting them as integral to a person’s experience of pain:

I think ACT is much more compassionate … not dwelling on certain thoughts and analysing certain thoughts as a cognitive behavioural approach would do. Allows a patient to have that experience without being judgemental about it feeling it’s wrong and shouldn’t have it.

Value-based goals a profound motivation for positive change

Participants were positive about the value-based goals and described how they could become a very strong drive to help patients identify goals that would ‘keep them on track’ even through difficult times. However, they felt vulnerable as central to the challenge of setting value-based goals was the potential to expose distress and cause emotional discomfort for both patients and physiotherapists. This was described as potentially opening a ‘can of worms’ that some of the physiotherapists felt they did not have the professional background and skills to deal with:

I think [value-based goals are] an even stronger driver to work towards … a value can be the driver behind all that … A goal might not be achieved but the value can still be there and you can work towards the value in different ways … it’s a deeper more profound motivation to change and to behave and to work or strive towards.

Participants described how setting value-based goals for themselves helped them to understand this, but this could also be quite emotional:

It’s quite profound; it’s quite personal and can be quite emotional … It’s something that is very core to being and to an individual as a person.

There was one man who refused to do the values and he didn’t want to participate in the session … he said that I had exposed him. He felt quite vulnerable I think … having to open up and disclose very personal information was difficult for him.

Participants describe the challenge of exposing emotions through value-based goal setting and the subsequent fall-out after the session from ‘opening a can of worms’:

I am not a psychologist, I am a physiotherapist. I don’t know whether it is fair to expect me to do all of that and I don’t know if anyone is expecting me to.

Someone bringing out a lot about their past or perhaps a very complex situation … we don’t want to say the wrong thing and it be to someone’s detriment … you don’t want to open this can of worms … you can’t put any of those worms back again.

It’s quite a long way from physiotherapy

The final theme described the tension between (a) a non-prescriptive exercise approach where the patients make decisions about exercise intensity and dosage and (b) traditional exercise therapy where the physiotherapist gave advice about progressively graded exercises. Physiotherapists described the challenge of allowing patients to ‘make mistakes’ and over-do exercises, knowing from professional experience that the patient might increase their pain as a result. They described this as a long way from physiotherapy:

I recognise that … we are trying to promote learning by giving choice and allowing people to get it wrong, to get it right, as we learn by doing not by being told what to do. I get that, although it is still hard as a physiotherapist not to give advice when I see … that the advice can be really helpful … is hard.

We struggle with the non-prescriptive component, the experiential component. Allowing the patient to work out for themselves what is too much and what is too little. Traditionally there is a protocol of exercises and ACT doesn’t really follow that. ACT allows the patient to make their own judgements on how they would like to respond … that is quite hard when you are watching a patient over-do [exercise].

Physiotherapist explored the personal challenge involved with adopting an approach that did not match their professional training and clinical experience, ‘the words come out before you even think about it’. First, physiotherapists are trained to try and fix a problem; second, they are experts in exercise prescription. They described uncertainty about which exercise approach to take within ACT; specifically, how much, if at all, should they direct exercises? This was particularly challenging because some felt that exercise prescription should be an area that they were ‘at home with’:

The other hard thing for therapists is that we have very much ingrained in us to try and problem solve to help someone fix a problem and I think that’s if someone says their pain levels are up we say ‘why do you think that has happened?’

We should feel most comfortable, in the gym and it’s where we feel a little uncomfortable … maybe I feel more uncomfortable knowing what to say in the more psychology based talks, but then … I feel OK to be uncomfortable in those areas because actually that is not my profession … we should be expert on exercise shouldn’t we? That is what our jobs are, so it’s probably a harder place to feel a bit uncomfortable.

There were also concerns that this might not actually be the right approach to exercise therapy and that by ignoring their training and experience, we may be ‘throwing the baby out with the bathwater’.

Despite the challenges of a non-prescriptive approach to exercise, some felt that graded progressive exercises could place a lot of pressure on patients and leave them with a feeling that they had failed if they did not manage to continue progression:

When you are talking about pacing and building up it’s as if it is a process that will never end. And actually probably for some people they will go so far and there will probably be some sort of plateau … and if we are trying to sell that message … it’s not the right expectation perhaps to give people.

I think pacing puts a lot of pressure on patients ’cos they think if they are not doing it they are going to fail. It sets them up for a failure really doesn’t it, especially if the patients are really chronic … it somehow enforces a sense of you are not disciplined enough if you can’t pace and it’s a way of a patient beating themselves up.

Discussion

The Action Research study presented here provides insight into the experiences of staff during the introduction of a service transformation project that introduced ACT to a pain rehabilitation programme. Overall, the group recognised both before the project started and afterwards that ACT was a positive progression in the field of pain management and one that sat comfortably with the skill set of other psychological-based therapeutic tools used by physiotherapists. However, some had concerns about the change from the tried and tested model of care. This supports other studies exploring the introduction of ACT in psychologists by Lappalainen et al.21 and Luoma and Vilardaga.11 However, we were seeking to move to an ACT-based programme using physiotherapists, who have a very different core training and conceptual framework underpinning their training.

Our study draws closer parallels with the work of Barker and McCracken12 who examined the process of moving to ACT on the interdisciplinary team at the INPUT pain management unit at Guy’s and St Thomas’s Hospital in London. In all, 6 of their sample of 14 clinicians were physiotherapists. They reported that there was some tension between the different disciplines and that while nursing, physiotherapy and occupational therapy can directly promote psychological flexibility and operate in an ACT environment, the methods for doing this are far less well mapped out than for psychologists. They identified that those from a non-psychology background may need to be offered more support and direct training in how to select, modify or refine methods to fit with the shifting treatment approach.

It needs to be recognised that physiotherapists utilising techniques such as ACT within their treatment programmes have spent years learning and honing their existing skill set. Adopting a different conceptual psychological framework for the rehabilitation programme has the potential to challenge the idea of professionalism and core identity. The participants in our study identified that initially ACT felt a long way from the traditional physiotherapy role they were used to and felt it challenging to be removed from key skills such as exercise prescription and giving direct explanations about pain or activity pacing.

Using Action Research enabled the change to be agreed prior to implementation and incorporated all team members as key participants in developing the change and implementing it. This process was at the core of the iterative process of honing the intervention and mode of delivery and sharing the experiential learning acquired. The concept that practice is con-textually located and embedded in local culture was important in deciding to use an Action Research approach. The pain rehabilitation programme is centrally led by an advanced clinical specialist physiotherapist with extensive training and skills in psychological approaches to pain rehabilitation. Support is provided to the team by a clinical psychologist, but as a resource psychology is over-stretched and the total input available is limited in time. Thus, the organisational culture and framework for this physiotherapy-led pain rehabilitation programme may be distinct from units that have a greater range of interdisciplinary input. As has been pointed out by other Action Research practitioners, merely having commonly defined purpose, goals and direction is not sufficient to alter the context within which clinicians operate.22 Instead, there was a need to also utilise intuition, emotions and pragmatism to reflect and challenge the habitual way of seeing and doing things and through discussion, reflective sessions and critical companionship to consider interlinked and interconnected issues. There was a need to introduce a challenging and potentially uncomfortable change within an environment that was psychologically safe. Further training was also provided from a team of experts once the approach had been introduced and used for some months. This gave an external safe environment to explore successes and failures and bolstered esteem, self-recognition of progress made and enthusiasm and pride in the changes already achieved.

Hart and Bond23 and Hall24 consider whether Action Research projects are best led by a practitioner, a researcher or a partnership of both. Key to successful Action Research is the close collaboration between the researcher and the other stakeholders and team members. There is a tension in the expectation that a practitioner who is researching changes in their own area and own practices can truly be neutral and dispassionate about the data they collect. For this reason, we chose to use a team to complete this study with the change introduced and led by the clinical practitioner (L.H.), supported managerially and for project management by the lead researcher and clinical director of the service (K.L.B.) and use an experienced qualitative researcher who had no managerial or clinical links with the team (F.T.). This shared leadership brought rigour to the study with expertise in design, data collection, analysis and interpretation. However, all data came from the clinical research participants who commented on emerging themes, contributed to the interpretation and findings from the study and allowed collective rather than individual interpretations to develop.

Acknowledgments

The input of the clinicians working within the Optimise programme is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This trial was supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Unit at Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences, University of Oxford.

References

- 1. Eccleston C, Williams AC, Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 2: CD007407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McCracken LM, Vowles KE. Acceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness for chronic pain. Am Psychol 2014; 69(2): 178–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wicksell RK, Kemani M, Jensen K, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy for fibromyalgia: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Pain 2013; 17: 599–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wetherell JL, Afari N, Rutledge T, et al. A randomised controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy for chronic pain. Pain 2011; 152: 2098–2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ost L-G. The efficacy of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Res Ther 2014; 61: 105–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vowles KE, Witkiewitz K, Sowden G, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: evidence of mediation and clinically significant change following an abbreviated interdisciplinary program of rehabilitation. J Pain 2014; 1: 101–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McCracken LM, Sato A, Taylor GJ. A trial of a brief group-based form of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for chronic pain in general practice: pilot outcome and process results. J Pain 2013; 14: 1398–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Van Green J, Edelaar M, Janssen M, et al. The long term effect of multidisciplinary back training: a systematic review. Spine 2007; 32: 249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Richards MC, Ford JJ, Slater SL, et al. The effectiveness of physiotherapy functional restoration for post-acute low back pain: a systematic review. Man Ther 2013; 18: 4–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Trompetter HR, Schreurs KMG, Heuts PHTG, et al. The systematic implementation of Acceptance and Commitment therapy (ACT) in Dutch multidisciplinary chronic pain rehabilitation. Patient Educ Couns 2014; 96: 249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Luoma JB, Vilardaga JP. Improving therapist psychological flexibility while training acceptance and commitment therapy: a pilot study. Cogn Behav Ther 2013; 42: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barker E, McCracken LM. From traditional cognitive-behavioural therapy to acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a mixed methods study of staff experiences of change. Br J Pain 2014; 8: 98–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework. Qual Health Care 1998; 7: 149–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Meyer J. Using qualitative methods in health related action research. BMJ 2000; 320: 178–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McNiff J, Whitehead J. All you need to know about action research, 2nd edn. London: SAGE, 2011, pp.7–41. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Winter R, Munn-Giddings C. A handbook for action research in health and social care. London: Routledge, 2001, pp. 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brown D, McCormack BG. Developing the practice context to enable more effective pain management with older people: an action research approach. Implement Sci 2011; 6: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McCormack B. Practitioner research. In:Hardy S, Titchen A, McCormack B, et al. (eds) Revealing nursing expertise through practitioner enquiry. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2009, pp. 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Titchen A. Helping relationships for practice development: critical companionship. In: McCormack B, Manley K, Garbett R. (eds) Practice development in nursing. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004, pp. 148–174. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lappalainen R, Lehtonen T, Skarp E, et al. The impact of CBT and ACT models using psychology trainee therapists: a preliminary controlled effectiveness trial. Behav Modif 2007; 31: 488–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schein EH. Organisational culture and leadership, 3rd edn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hart E, Bond M. Action Research for Health and Social Care – a guide to practice. Buckingham: Open University Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hall JE. Professionalizing action research – a meaningful strategy for modernizing services? J Nurs Manag 2006; 14: 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]