Abstract

AKI confers increased risk of progression to CKD. αKlotho is a cytoprotective protein, the expression of which is reduced in AKI, but the relationship of αKlotho expression level to AKI progression to CKD has not been studied. We altered systemic αKlotho levels by genetic manipulation, phosphate loading, or aging and examined the effect on long-term outcome after AKI in two models: bilateral ischemia-reperfusion injury and unilateral nephrectomy plus contralateral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Despite apparent initial complete recovery of renal function, both types of AKI eventually progressed to CKD, with decreased creatinine clearance, hyperphosphatemia, and renal fibrosis. Compared with wild-type mice, heterozygous αKlotho–hypomorphic mice (αKlotho haploinsufficiency) progressed to CKD much faster, whereas αKlotho-overexpressing mice had better preserved renal function after AKI. High phosphate diet exacerbated αKlotho deficiency after AKI, dramatically increased renal fibrosis, and accelerated CKD progression. Recombinant αKlotho administration after AKI accelerated renal recovery and reduced renal fibrosis. Compared with wild-type conditions, αKlotho deficiency and overexpression are associated with lower and higher autophagic flux in the kidney, respectively. Upregulation of autophagy protected kidney cells in culture from oxidative stress and reduced collagen 1 accumulation. We propose that αKlotho upregulates autophagy, attenuates ischemic injury, mitigates renal fibrosis, and retards AKI progression to CKD.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, chronic kidney disease, autophagy, renal fibrosis, ischemia-reperfusion injury, αKlotho

AKI confers formidable morbidity and mortality in its acute phase, especially in the intensive care unit setting, where mortality is as high as 50%.1,2 Among survivors of AKI, the long-term outcome is far from benign. Patients who recover from AKI have a 25% increase in risk for CKD and a 50% increase in mortality after follow-up of approximately 10 years.3,4 Although clinical observations describe a clear association, they do not establish a causal link between AKI and CKD; human data from longitudinal post–AKI cohorts will be required but will take many years to obtain. As an initial exploration of this paradigm, we used rodent AKI models to examine CKD progression post-AKI with emphasis on the role of αKlotho post-AKI.

Klotho was initially discovered as an antiaging protein5 and is now called αKlotho to distinguish it from two other paralogs: βKlotho6 and γKlotho.7 αKlotho is a type 1 transmembrane protein highly expressed in the kidney and brain.8 The extracellular domain of transmembrane αKlotho can be released into the circulation as soluble αKlotho by secretases9–12 and functions as an endocrine factor to exert a myriad of biologic effects on multiple target organs.13,14 αKlotho is involved in cytoprotection, antiapoptosis, anticell senescence, and antifibrosis, all of which may be crucial in tissue protection and regeneration.15,16 Animal studies have shown that (1) AKI from ischemic injury and AKI from cisplatin nephrotoxicity are transient states of αKlotho deficiency,17,18 (2) αKlotho protects the kidney from ischemic AKI when given immediately after the insult,18 and (3) restoration of αKlotho after established unilateral ureteral obstruction can prevent subsequent renal fibrosis.19,20 Clinical observational studies have shown αKlotho deficiency in both AKI18 and CKD.15,21,22 The relationship between αKlotho deficiency and CKD progression post-AKI has not been examined. This is a critical but unexplored pathophysiologic mechanism with immense therapeutic potential.

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved catabolic process for lysosomal degradation or recycling of cytoplasmic components and serves as a defense mechanism to protect and maintain normal cellular function.23–25 Defective or excessive autophagic flux contributes to aging and various diseases in humans.25,26 In ischemia-27,28 or cisplatin-induced29–33 AKI and unilateral ureteral obstruction,34,35 autophagy is activated. Several lines of evidence in animals showed that defective autophagy renders the kidney vulnerable to ischemic injury and nephrotoxicity.29–34,36,37 Dysfunction in autophagy also contributes to aging in all organs and tissues.38–40 Associations between the levels of autophagy and αKlotho have previously been reported, but the results were not consistent.41–44 Furthermore, whether the renoprotection rendered by αKlotho is related to modulation of autophagy has not been studied.

There were several objectives in this study. First, we strived to define appropriate AKI models that spontaneously and reliably progress to CKD. Second, we examined whether renal αKlotho deficiency is associated with CKD development post-AKI, and we manipulated endogenous αKlotho levels to examine whether its deficiency has a causal role in CKD. Third, we sought to define the therapeutic effect of αKlotho on the blockage of AKI progression to CKD. Fourth, we explored whether changes in αKlotho levels are associated with and alter levels of autophagy, cytoprotection, and extracellular matrix accumulation. Our studies establish a novel mechanistic link between αKlotho, autophagy, and renoprotection against fibrosis and post-AKI progression to CKD. We propose that the αKlotho deficiency leads to insufficient autophagy and renders the kidney more vulnerable to ischemic injury and that αKlotho administration post-AKI is a potential therapeutic agent for promotion of kidney recovery, suppression of renal fibrosis post-AKI, and prevention of progression to CKD.

Results

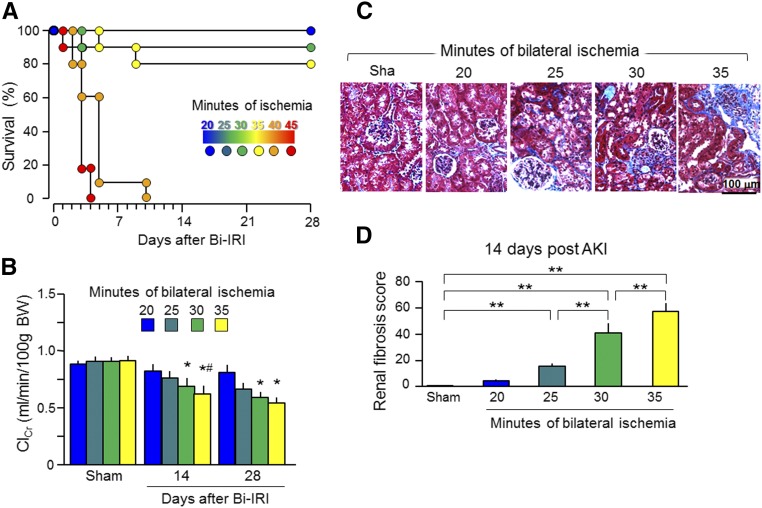

Recovery after Severe AKI

Because clinical observational studies have not been able to establish a causal link between AKI and CKD, we used animal models to longitudinally examine CKD progression post-AKI. Mice that underwent bilateral ischemia-reperfusion injury (Bi-IRI) or unilateral nephrectomy plus contralateral ischemia-reperfusion injury (Npx-IRI) were fed normal rodent chow and followed for 20 weeks after this single episode of AKI. Because more severe AKI is associated with worse long–term outcome, including higher mortality and incidence of CKD,3,4,45 we used the Bi-IRI model to vary the duration of ischemia to titrate the severity of AKI. Forty minutes of ischemia or longer led to no survival beyond 10 days (Figure 1A). Creatinine clearance (ClCr) was lower in the 35-minute than in the 20-minute ischemia group at 2 weeks and did not completely return to baseline in the 35- and 30-minute ischemia groups at 4 weeks after ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) (Figure 1B). At 2 weeks post-AKI, when ClCr was only slightly reduced, renal fibrosis was marked and more prominent in the 35- and 30-minute ischemia groups compared with the 20-minute ischemia group (Figure 1, C and D). More severe kidney injury induced by longer periods of ischemia should lead to maladaptive repair shown by fibrosis, a well known hallmark of CKD and a final and common pathogenic pathway to development of CKD.46,47 We reasoned that renal fibrosis at 14 days post-AKI is likely to be the precursor of eventual CKD.

Figure 1.

Severe AKI leads to poor outcome. Three-month-old WT mice underwent Bi-IRI with different duration of ischemia and then were fed normal rodent chow for ≤28 days. (A) Survival rate. (B) ClCr. Data are expressed as means±SDs of at least four mice from each group, and statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test, and accepted when *P<0.05 versus 20 minutes; #P<0.05 versus 25 minutes on the same day. BW, body weight. (C) Representative Trichrome stain of kidney sections at 14 days post-AKI. (D) Renal fibrosis scores obtained from a Trichrome-stained section with ImageJ. Data are expressed as means±SDs of four mice from each group, and statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test, and accepted when **P<0.01 between two groups.

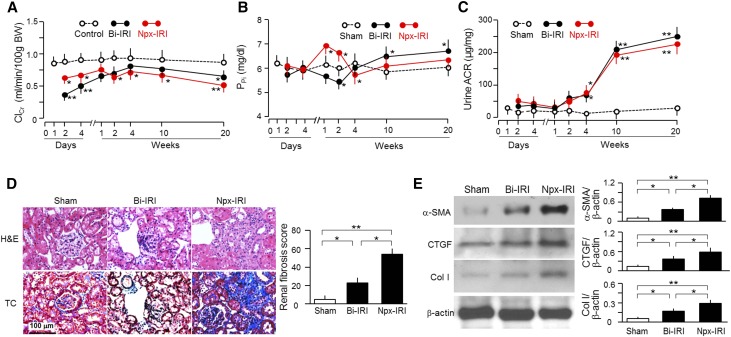

Murine Model of Post-AKI CKD

In both Bi-IRI and Npx-IRI groups, ClCr rapidly decreased to trough levels at 2 days followed by slow return to near-control levels within approximately 1–2 weeks. After 4 weeks of AKI, ClCr started to decline slowly but progressively to approximately 60% of normal renal function by 20 weeks (Figure 2A). Therefore, AKI progressed to CKD by 20 weeks after exposure to just one single episode of renal insult.

Figure 2.

AKI mice develop CKD. Three-month-old WT mice were subjected to 30-minute Bi-IRI or 30-minute Npx-IRI and then fed normal rodent chow for 20 weeks. Blood and urine were collected at designated times for (A) ClCr, (B) PPi, and (C) urine ACR. Data are expressed as means±SDs of at least four mice from each group, and statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test, and accepted when *P<0.05; **P<0.01 versus sham at the same time point for A–C. BW, body weight. (D) Kidney morphology by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Trichrome (TC) staining. (Left panel) Representative micrographs in kidney sections from animals of each group. (Right panel) Renal fibrosis scores obtained from TC-stained sections analyzed with ImageJ. At least four animals were included in each group. (E) Fibrotic markers in the kidney. (Left panel) Representative immunoblot for α-SMA, CTGF, Col I, and β-actin in total kidney lysates. (Right panel) Summary of all immunoblots. Data are expressed as means±SDs of at least four mice from each group, and statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test, and accepted when *P<0.05; **P<0.01 between two groups for D and E.

In addition to decline of ClCr, disturbed phosphate homeostasis is another aspect of CKD that can affect extrarenal complications and survival.48–50 The two models displayed differential patterns. In the Npx-IRI group, plasma phosphate (PPi) was increased within 1 week followed by normalization after 4 weeks; PPi in Bi-IRI was transiently decreased after 2 weeks followed by sustained elevation after 4 weeks. By 20 weeks after AKI, mice in the Bi-IRI group had severe hyperphosphatemia, but mice in the Npx-IRI group had a milder degree of hyperphosphatemia (Figure 2B). In contrast to the heterogeneous change in PPi, the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR), a predictor of CKD progression,51 was consistently and similarly elevated after 4 weeks and further increased in 20 weeks in both groups (Figure 2C).

Kidney histology with hematoxylin and eosin, Trichrome (Figure 2D, left panel), and periodic acid–Schiff stains (Supplemental Figure 1) showed glomerular collapse, tubular dilation, tubulointerstitial infiltration, and fibrosis in both models. Bi-IRI mice had less renal fibrosis but seemed to have more appreciable renal tubular dilation. Renal fibrosis scores (Figure 2D, right panel) provided semiquantitative information of the Trichrome findings. The changes in fibrotic markers (α-smooth muscle actin [α-SMA], connective tissue growth factor [CTGF], and collagen 1 [Col I]) by immunoblot were consistent with the Trichrome staining, showing a robust increase in the Npx-IRI group and a less severe but still significant increase in the Bi-IRI group (Figure 2E). Thus, at 20 weeks, there was a difference in severity between the Npx-IRI and Bi-IRI models, but all of the animals had CKD with predominant fibrotic components.

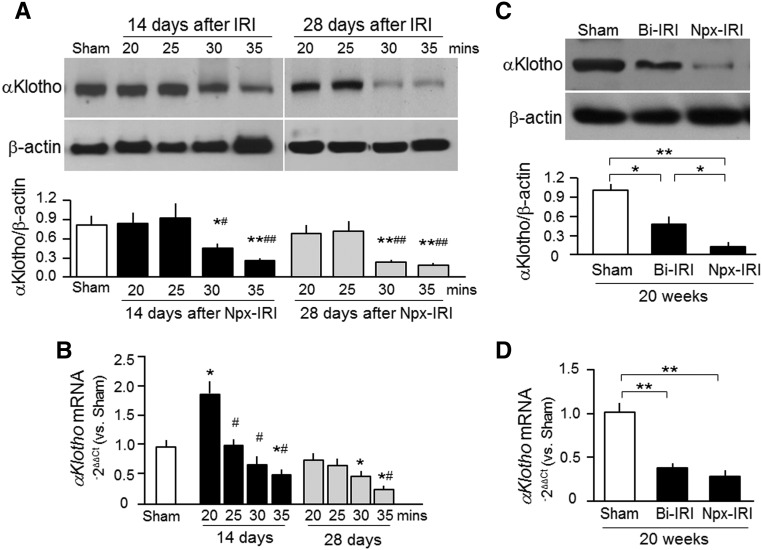

Renal αKlotho Expression during AKI Progression to CKD

We15,17,18,52 and others53–55 have shown transient renal αKlotho deficiency in AKI and sustained renal αKlotho deficiency in CKD. However, the time profile of αKlotho alterations during the course of AKI progression to CKD has not been examined. The decrease in αKlotho is dependent on the severity of the insults (duration of ischemia) and the number of weeks after the injury. We found normalization of renal αKlotho expression by about 10 days, but the expression decreased again around 14 days after IRI in the ≥30-minute ischemia groups, with yet further decline by 28 days (Figure 3A). Interestingly, in the 20-minute ischemia group, αKlotho mRNA even temporally exceeded normal at 14 days and returned to the levels of the sham group (Figure 3B), indicating that mild ischemia may upregulate αKlotho mRNA in the kidney in a manner akin to preconditioned hypoxia, which can upregulate hypoxia-inducible factor to prevent tissue against additional hypoxia–induced damage.56,57 In the 30- and 35-minute groups, αKlotho mRNA was universally reduced by 14 days. By 28 days, αKlotho mRNA tended to rise in the 30-minute group but remained low in the 35-minute group (Figure 3B), indicating that the more severe insult from longer ischemia leads to persistent and irreversible decline in αKlotho protein and mRNA.

Figure 3.

Renal αKlotho deficiency is present in the course of AKI transition to CKD. (A and B) Three-month-old WT mice underwent Npx-IRI with different durations of ischemia and then were fed normal rodent chow for ≤28 days. (A) Representative immunoblots for αKlotho protein in the kidney are shown in upper panel. Lower panel is a summary of the immunoblots of three independent experiments. (B) αKlotho mRNA expression in the kidney by qPCR. Results are expressed as 2−ΔΔCt with normalization to cyclophilin and then a ratio to the sham group. Data are expressed as means±SDs of three mice from each group, and statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test, and accepted when *P<0.05; **P<0.01 versus sham group; #P<0.05; ##P<0.01 versus 20 minutes. (C and D) Three-month-old WT mice were subjected to Bi-IRI or Npx-IRI and then fed normal rodent chow for 20 weeks. (C) Representative immunoblots for αKlotho and β-actin protein in the kidney (upper panel). Lower panel is a summary of immunoblots of three independent experiments. Data are expressed as means±SDs, and statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test. (D) αKlotho mRNA expression in the kidney was analyzed with qPCR. Results are expressed as 2−ΔΔCt (Ct cycle number) by normalization to cyclophilin and then a ratio to the sham group. Data are expressed as means±SDs of three mice from each group, and statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test, and accepted when *P<0.05; **P<0.01 between two groups.

Next, we compared the severity of αKlotho deficiency at 20 weeks after AKI. αKlotho protein and mRNA expression in the kidney was reduced in both models (Figure 3, C and D), with mice from the Bi-IRI group having slightly higher αKlotho protein in the kidney. This further confirms that CKD is a state of renal αKlotho deficiency as shown previously.15,52–54

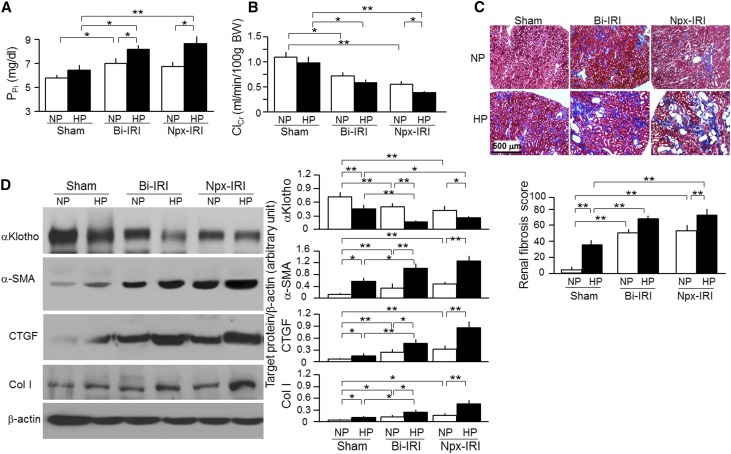

Effect of Chronic High Dietary Phosphate Intake on Renal Fibrosis after AKI

Hyperphosphatemia is associated with cardiovascular disease in CKD,48–50,58–60 but the role of phosphate as a modulator for AKI transition to CKD is not known. We fed mice high–phosphate (2%) rodent chow for 18 weeks starting at 2 weeks post-AKI, when renal recovery has already transpired. High-phosphate diet led to minor elevations of PPi in sham mice but significantly increased PPi in both Bi-IRI and Npx-IRI mice (Figure 4A). Interestingly, ClCr slightly decreased, even in sham mice fed with high-phosphate diet (Figure 4B), and was drastically reduced in Npx-IRI mice but just slightly reduced in Bi-IRI mice, suggesting that phosphate loading may accelerate the AKI to CKD transition, particularly in mice with renal mass loss. Trichrome staining showed slightly but appreciably increased renal fibrosis in sham mice fed high phosphate and a robust increase in fibrosis in both Bi-IRI and Npx-IRI mice fed high-phosphate diet compared with normal-phosphate diet (Figure 4C). High-phosphate diet also induced more drastic histologic changes, including glomerular collapse, dilated renal tubules, and renal tubular atrophy, in both sham and two IRI models (Supplemental Figure 1). Consistent with the increase in histologic fibrosis, α-SMA, CTGF, and Col I protein were increased in Bi-IRI and Npx-IRI compared with sham mice and further increased by dietary phosphate loading (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Low renal αKlotho is associated with more severe renal fibrosis in mice fed with a high Pi diet. Three-month-old WT mice underwent Bi-IRI, Npx-IRI, or laparotomy for sham and were fed normal–phosphate rodent chow (NP; 0.7%) or high-Pi diet (HP; 2.0% Pi) for 18 weeks starting 2 weeks after surgery. (A) PPi. (B) ClCr. BW, body weight. (C) Renal fibrosis at 20 weeks. (Upper panel) Representative micrographs of Trichrome staining in the kidney sections. Scale bar, 500 μm. (Lower panel) Renal fibrosis scores were obtained from Trichrome-stained sections with ImageJ. (D) αKlotho and fibrotic markers in the kidney. (Left panel) Representative immunoblotting for αKlotho, α-SMA, CTGF, Col I, and β-actin protein. (Right panel) Summary of immunoblots in arbitrary units from all immunoblots. Data are expressed as means±SDs of at least four mice from each group, and statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test. Significant difference was accepted when *P<0.05; **P<0.01 between two groups.

The phosphate effect may be direct, or it may act through other intermediates. We previously showed that phosphate can lower renal and circulating Klotho.48 αKlotho protein expression was significantly reduced by phosphate loading in all groups, including sham, Bi-IRI, and Npx-IRI mice (Figure 4D), indicating that phosphate suppresses αKlotho expression in the kidney, regardless of whether there is underlying kidney disease, through yet to be determined mechanism(s). We propose that the detrimental effects of phosphate loading may be, in part, through suppression of αKlotho.

αKlotho Level and CKD Progression after AKI

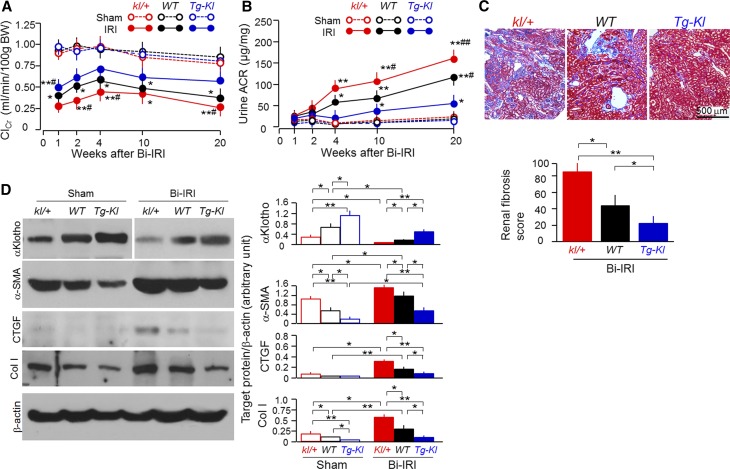

To explore the relationship between αKlotho levels and renal outcome, we generated Bi-IRI–induced CKD in kl/+ (heterozygous αKlotho hypomorphic mouse line5 with αKlotho levels approximately 50% normal), WT (normal αKlotho levels), and Tg-Kl (transgenic mouse line that ubiquitously overexpresses mouse Klotho5 with αKlotho levels approximately 150% normal) mice. One week after IRI, ClCr was lower in kl/+ and higher in Tg-Kl mice compared with WT mice (Figure 5A). In addition, the rate of ClCr decline was much sharper in kl/+ mice than in WT mice. ACR started to increase at 1 week post-IRI, but Tg-Kl mice had much lower and kl/+ mice had higher ACR than WT mice (Figure 5B). Therefore, αKlotho-deficient mice had faster and αKlotho-overexpressing mice slower development of CKD. By 20 weeks, kl/+ mice had massive interstitial fibrosis, whereas Tg-Kl mice had very minor alterations compared with WT mice (Figure 5C). By 20 weeks, Tg-Kl mice maintained αKlotho protein levels in the kidney comparable with those of WT mice not subjected to AKI, but kl/+ mice had much lower levels of αKlotho protein than those of WT mice (Figure 5D). α-SMA, CTGF, and Col I protein in the kidney were lower in Tg-Kl and higher in kl/+ mice compared with those in WT mice (Figure 5D), consistent with the renal fibrosis shown by Trichrome staining. Therefore, αKlotho-deficient mice have a higher risk of development of fibrosis and progression to CKD.

Figure 5.

αKlotho-deficient mice have more rapid progression to CKD after AKI. Mice with three different levels of αKlotho (low, kl/+; normal, WT; high, Tg-Kl) at 3 months old underwent Bi-IRI and were fed normal rodent chow for 20 weeks. (A) ClCr. BW, body weight. (B) Urine ACR. Data are expressed as means±SDs of at least four mice from each group, and statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test, and accepted when *P<0.05; **P<0.01 versus vehicle at same age; #P<0.05; ##P<0.01 versus IRI Tg-Kl mice. (C) Renal fibrosis at 20 weeks. (Upper panel) Representative micrographs of Trichrome staining of kidney sections from four animals of each group. (Lower panel) Summary of renal fibrosis scores obtained from Trichrome-stained sections with ImageJ. (D) Levels of αKlotho and fibrotic markers in the kidney. (Left panel) Representative immunoblots for αKlotho, α-SMA, CTGF, Col I, and β-actin protein. (Right panel) Summary of immunoblots. Data are expressed as means±SDs of four mice from each group, and statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test, and accepted when *P<0.05; **P<0.01 between two groups.

αKlotho Protein Administration Promotes Kidney Recovery and Reduces Renal Fibrosis

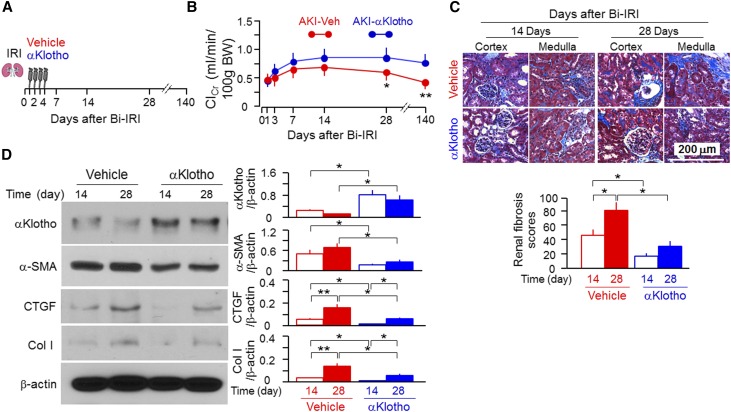

Genetic manipulations of αKlotho levels serve as proof-of-principle experiments, but eventual therapeutic translation requires testing the effects of exogenous recombinant αKlotho protein on the course of AKI and the AKI to CKD transition. We injected αKlotho protein 1 day after IRI, when kidney injury was fully established, plasma creatinine (PCr) had peaked, and αKlotho protein in the kidney was at its lowest levels.18,55 We continued daily injections for 4 days (Figure 6A). Although there was no change in the trough ClCr, which is expected given the timing of the injection, αKlotho administration was effective in promoting kidney recovery as evidenced by a faster rise in ClCr (Figure 6B) and less fibrosis (Figure 6C). In addition, there were higher levels of αKlotho expression and lower fibrogenic markers in the kidneys of αKlotho-treated than vehicle-treated AKI mice (Figure 6D), indicating that exogenous αKlotho administration preserves renal αKlotho expression and suppresses fibrosis. When we followed the animals ≤140 days, we found that mice without αKlotho treatment developed CKD after IRI as evidenced by a drastic reduction of ClCr compared with mice treated with αKlotho (Figure 6B), indicating that early administration of αKlotho, even for a brief period of time, protects AKI to CKD transition.

Figure 6.

Soluble αKlotho protein promotes renal recovery and mitigates renal fibrosis in WT mice after Bi-IRI. (A) Three-month-old WT mice were intraperitoneally given αKlotho protein (0.01 mg/kg) for 4 consecutive days starting 24 hours after Bi-IRI. Mice were euthanized at 14, 28, and 140 days after surgery. (B) ClCr. BW, body weight. Data are expressed as means±SDs of at least four mice from each group, and statistical significance was assessed by unpaired t test. Statistical significance was accepted when *P<0.05; **P<0.01 versus vehicle. (C) Renal fibrosis at 14 and 28 days. (Upper panel) Representative micrographs of Trichrome staining in the kidney sections. Scale bar, 500 μm. (Lower panel) Renal fibrosis scores were obtained from Trichrome-stained sections with ImageJ. (D) αKlotho and fibrotic markers in the kidney. (Left panel) Representative immunoblotting for αKlotho, α-SMA, CTGF, Col I, and β-actin protein. (Right panel) Summary of arbitrary units from all immunoblots. Data are expressed as means±SDs of four mice from each group, and statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test. Statistical significance was accepted when *P<0.05; **P<0.01 between two groups.

αKlotho Deficiency Reduces and αKlotho Overexpression Restores Autophagy in the Kidney

Comparable with published results,26,27,29,31,61,62 autophagy was activated by Bi-IRI as evidenced by the higher LC3-II–to–LC3-I ratios in the kidney at day 2 (Supplemental Figure 2A) and an increase in the punctate pattern of fluorescent LC3 in renal tubules of transgenic GFP-LC3 reporter mice (Supplemental Figure 2B). As a separate examination from the AKI model, we explored the association of αKlotho levels with the state of autophagic flux in the kidney at baseline by measuring renal p62 protein levels and LC3-I to LC3-II conversion, well established markers for monitoring autophagy activity.63,64 Higher levels of p62 protein and lower ratios of LC3-II to LC3-I were found in the kidneys of kl/kl mice compared with WT mice, and a significant decrease in p62 and a slight increase in LC3-II–to–LC3-I ratios were found in the kidney of Tg-Kl mice (Supplemental Figure 2C), suggesting that αKlotho deficiency induces defective autophagy in the kidney at the baseline unperturbed state.

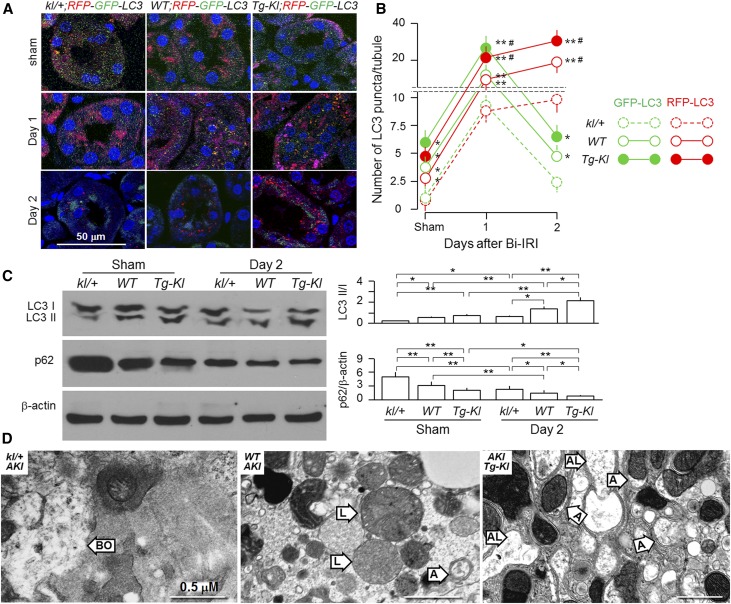

To directly explore the relationship between αKlotho levels and autophagy flux in the kidney after acute ischemic injury, we crossmated a mouse line with two autophagy reporters (RFP;GFP-LC3)62 with kl/+, WT, or Tg-Kl mice to generate three new lines: kl/+;RFP;GFP-LC3, WT;RFP;GFP-LC3, and Tg-Kl;RFP;GFP-LC3. As shown in Figure 7, A–C, the IRI-induced upregulation of autophagy flux was more robust in Tg-Kl versus WT mice and less robust in kl/+ versus WT mice at day 1 on the basis of RFP and GFP signals. However, on day 2, GFP-LC3 signal declined in all three mouse lines; in contrast, RFP-LC3 signal even slightly increased. These results support the finding of Lin et al.65 that RFP-LC3 is a more reliable marker for autophagy flux than GFP-LC3 and that the RFP;GFP-LC3-reporter mouse can be used to monitor the dynamics of autophagy change in the kidney in response to IRI. In addition, IRI–induced LC3 punctae were prominently present in proximal tubules, weakly present in thick ascending limbs, and not present in distal tubules (Supplemental Figure 3), which is comparable with data in the literature.27,29,32,33,62,66

Figure 7.

αKlotho upregulates autophagy and attenuates kidney injury induced by Bi-IRI. Three-month-old mice with three different genetic αKlotho levels and RFP;GFP-LC3 reporter were subjected to Bi-IRI (30-minute ischemia followed by a reperfusion of 1 or 2 days). Sham operation serves as control. (A) Immunofluorescence images for LC3 punctae in the kidneys. Red signal represents RFP-LC3, green signal represents GFP-LC3, yellow signal represents merge of RFP-LC3 with GFP-LC3, and blue signal represents Syto 61 for nuclear stain. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) The number of RFP-LC3 and GFP-LC3 punctae per renal tubule after analysis of 50 proximal tubules in the zone of cortex plus outer medulla. Results are means±SDs from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test. Statistical significance was accepted when *P<0.05; **P<0.01 versus kl/+ mice; statistical significance was accepted when #P<0.05; ##P<0.01 versus WT mice on same day. (C) Expression of LC3-I and LC3-II and p62 protein in the kidney of mice with three different genetic αKlotho levels at day 2 post-IRI. (Left panel) Representative immunoblots for LC3-II/LC3-I, p62, and β-actin protein in the kidney. (Right panel) Summary of immunoblots from three independent experiments. Results are means±SDs from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test. Statistical significance was accepted when *P<0.05; **P<0.01 between two groups. (D) Representative transmission electron microscopic images of autophagic structures in the kidney of mice with three different genetic αKlotho levels at 2 days post-IRI. A, autophagosome; AL, autophagolysosome; BO, broken organelle in necrotic cells; L, lysosome. Scale bar, 0.5 μm.

Noticeably, αKlotho-deficient mice with AKI had severe kidney damage as evidenced by severe necrotic features, such as disintegrated nuclei and broken plasma membrane and organelles, whereas αKlotho-overexpressing mice subjected to AKI had much milder kidney damage and more autophagosomes and autolysosomes in the kidney. WT mice had intermediate features in the kidney (Figure 7D, Supplemental Figure 4).

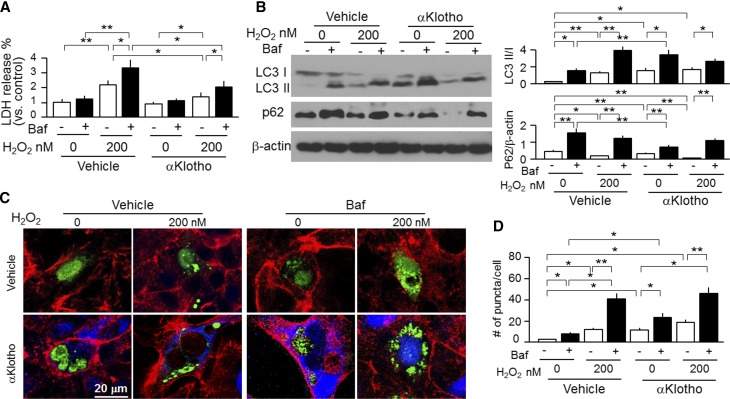

αKlotho Upregulates Autophagic Flux and Protects Kidney Cells In Vitro against Oxidative Stress

Because autophagy suppresses apoptosis and protects against cellular demise in most instances,67 we examined the effect of αKlotho on a proximal tubular cell line (opossums kidney [OK] cells) in vitro to more directly address whether αKlotho’s cytoprotection is associated with autophagy modulation. We mimicked IRI with H2O2 and found that H2O2–induced lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release was reduced by coincubation with αKlotho (Figure 8A) as previously reported.16 The new finding, however, was that αKlotho increased the LC3-II–to–LC3-I ratios and decreased p62 protein in OK cells (Figure 8B) and increased the number of GPF-LC3 punctae (autophagosomes) in OK cells transfected with GFP-LC3 (Figure 8, C and D), thereby confirming the in vivo findings of higher baseline autophagic flux in the kidney of Tg-Kl mice compared with WT mice (Figure 7B). Bafilomycin A1 (Baf), an inhibitor of lysosomal acidification and also, an autophagy inhibitor,68 increased the ratios of LC3-II to LC3-I and p62 (Figure 8B), increased GPF-LC3 punctae (Figure 8, C and D), and also, blunted αKlotho-induced elevation of autophagic flux (Figure 8, B and C). Of note, Baf also significantly increased H2O2–induced LDH release (Figure 8A), indicating that suppression of autophagy by Baf rendered cells more susceptible to oxidative stress. Importantly, Baf partially but significantly blunted the αKlotho-induced cytoprotection as evidenced by an increased LDH release from OK cells (Figure 8A), which suggests that one of the mechanisms of αKlotho-induced cytoprotection is activation of autophagy. Because Baf is an inhibitor of late-phase autophagy by inhibition of fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes,68 3-methyladenine (3-MA), an inhibitor of early-phase autophagy by inhibition of autophagosomes formation,69 was tested; 3-MA rendered cells more susceptible to oxidative stress and partially blunted the αKlotho effect through reduction of autophagy activity (Supplemental Figure 5), akin to the Baf effect (Figure 8). Finally, a third autophagy inhibitor, wortmannin, had a similar effect (data not shown) as that of 3-MA. Therefore, upregulation of autophagy activity may be one of mechanisms of αKlotho’s cytoprotection.

Figure 8.

αKlotho upregulates autophagy and protects kidney cell against oxidative stress–induced cell injury. OK cells were treated with H2O2 with or without Baf (200 nM). In addition, recombinant αKlotho protein was added to examine whether αKlotho suppresses cell injury induced by H2O2. (A) LDH in supernatants released from OK cells was used for assessment of cell injury. (B) Protein expression of LC3-I, LC3-II, and p62 protein in OK cells. (Left panel) Representative immunoblots for LC3-I and LC3-II, p62, and β-actin protein. (Right panel) Summary of immunoblots from three independent experiments. Data are expressed as means±SDs. (C) Representative immunocytochemistry for αKlotho (blue), LC3 (green), and phalloidin (red) in OK cells. OK cells were seeded on coverslips and transfected with GFP-LC3 plasmid. After 24 hours of transfection, cells were treated with H2O2 and/or Baf. Vehicle (upper panel) or recombinant αKlotho protein (0.4 nM; lower panel) was added to examine whether αKlotho suppresses cell injury induced by H2O2 in the presence of αKlotho or vehicle for control for 24 hours. Scale bar, 20 μm. (D) Quantification of the number of GFP-LC3 punctae per cell in OK cells (100 cells analyzed per sample). Results represent as means±SDs from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test. Statistical significance was accepted when *P<0.05; **P<0.01 between two groups.

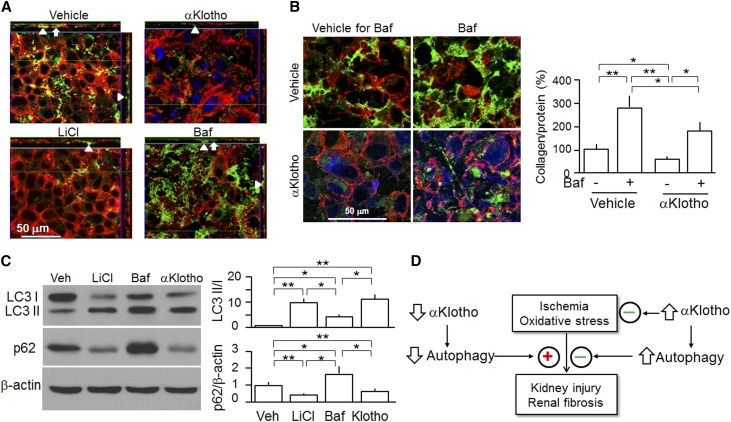

αKlotho Suppresses Collagen Accumulation

Another important aspect of AKI to CKD progression is renal fibrosis. To define the post-translational effects of autophagy on Col I metabolism in vitro, OK cells were cotransfected with CMV-GFP-Col I α2 (GFP-Col I) plasmid followed by treatment with active modulators of autophagic flux. As shown in Supplemental Figure 6, two autophagy inducers (LiCl and rapamycin) reduced but two autophagy inhibitors (Baf and wortmannin) increased Col I in OK cells, suggesting that autophagy participates in the maintenance of collagen balance in the cells and that defective autophagy reduces the cellular capacity to clear excessive Col I and subsequently, leads to Col I accumulation.

To directly evaluate the post-translational effects of αKlotho on collagen metabolism in vitro, GFP-Col I plasmid was transiently transfected into OK cells and treated with recombinant αKlotho protein. There was a dramatic decrease in extracellular and intracellular Col I accumulation (Figure 9, A and B), which was partially but significantly abolished by Baf (Figure 9B). To link the effect of LiCl, Baf, and αKlotho on collagen metabolism to modulation of autophagic flux, we measured LC3-II to LC3-I and p62 abundance. Both LiCl and αKlotho increased the LC3-II–to–LC3-I ratios and decreased p62 protein, whereas Baf slightly increased the LC3-II–to–LC3-I ratios but appreciably increased p62 protein (Figure 9C), suggesting that the αKlotho-induced reduction in Col I in OK cells is at least associated with upregulation of autophagic flux.

Figure 9.

αKlotho-induced reduction of Col I accumulation is associated with increase in autophagic flux in OK cells. OK cells were seeded on coverslips and transfected with GFP-Col I plasmid. After 24 hours of transfection, cells were treated with autophagy inducer (LiCl; 10 mM) or suppressor (Baf; 200 nM) or αKlotho (0.4 nM) or vehicle. Cells were stained with anti-αKlotho and examined by confocal fluorescent microscopy. Rhodamine-phalloidin served as the counterstain. (A) Representative immunocytochemistry for αKlotho (blue), Col I (green), and phalloidin (red) in OK cells analyzed by laser confocal microscopy. Intracellular collagen is depicted by arrows, and extracellular collagen accumulation is depicted by arrowheads. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B, left panel) Representative immunocytochemistry for αKlotho (blue), Col I (green), and phalloidin (red) in OK cells. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B, right panel) Collagen in OK cells stained and quantified with the Sirius Red/Fast Green Kit. (C) OK cells were treated with LiCl (10 mM), Baf (200 nM), and αKlotho (0.4 nM) versus vehicle for 24 hours, and lysates were immunoblotted. (Left panel) Representative immunoblots for LC3-I and LC3-II, p62, and β-actin. (Right panel) Summary of immunoblots from three independent experiments. Data are expressed as means±SDs, and statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test. Veh, vehicle. Statistical significance was accepted when *P<0.05; **P<0.01 between two groups. (D) Proposed working model of the effect of αKlotho on autophagy in AKI. αKlotho maintains a normal level of autophagy. Low αKlotho reduces and high αKlotho increases autophagic flux. Upregulation of autophagy exerts both cytoprotective and antifibrotic actions. In addition, αKlotho also protects the kidney against injury from oxidative stress or ischemia through antioxidation and antiapoptosis, which are independent of regulation of autophagy.

Discussion

The notion of AKI developing into CKD was derived from retrospective clinical observations.1,3 AKI is now considered to be an independent risk factor for the development of CKD.3,70 However, there are limited experimental data directly addressing the AKI to CKD transition; thus, evidence supporting a causal relationship between AKI and CKD is still lacking. Acute αKlotho deficiency is associated with ischemic kidney injury,18 cisplatin nephrotoxicity,17 and ureteral obstruction in rodents.19 However, whether αKlotho deficiency can promote CKD progression after a single renal insult has not been studied. We now provide experimental longitudinal data that support this notion.

One aim of this study was to create animal models of AKI to CKD progression to permit additional mechanistic and interventional studies. We used two different manipulations corresponding to presence versus absence of reduced nephron mass15,71 to test our hypothesis. Mice from both models developed CKD, despite initial recovery if the initial kidney damage was severe enough. Genetic αKlotho deficiency and high dietary phosphate accelerated CKD progression post-AKI. Phosphate toxicity is not only a consequence of declined renal function49 but also, a risk factor for promotion of CKD progression,72–74 ectopic calcification,15,58,59,75,76 and cardiovascular events48,50,60,77 in humans. We showed that phosphate reduced αKlotho in the kidney even in normal mice and further downregulated the already low αKlotho in the kidney of CKD mice.48 Thus, αKlotho deficiency may be one potential intermediator of phosphotoxicity, and αKlotho deficiency, in turn, further increases hyperphosphatemia.

αKlotho deficiency was shown to be a contributor to renal fibrosis.20,78–81 The observation of better preservation of kidney function in Tg-Kl with high renal and circulating αKlotho after renal insult15,17,18 cannot distinguish whether renal membrane αKlotho or circulating αKlotho plays a more important role in renoprotection. The administration of exogenous αKlotho (soluble αKlotho protein) promoted renal recovery and attenuated renal fibrosis, clearly supporting that soluble αKlotho is an active molecule. Importantly, ClCr was similar in the AKI-vehicle versus the AKI-αKlotho group at days 14 and 28, but renal fibrosis was more pronounced in the AKI-vehicle group, indicating that ClCr is not a sensitive and reliable marker for underlying renal pathology, perhaps because of functional compensation.

Autophagy is an intracellular degradation pathway in the maintenance of cellular homeostasis.25,67 Autophagy is activated in the kidney of AKI animals and purported to confer renoprotection.26,29–34,36,37 Although this study lacks in vivo data, the in vitro results support the cytoprotection of autophagy against oxidative stress–induced cell injury.

In vitro studies showed that αKlotho induces autophagy in cancer cell lines.44,82 The in vivo effects of αKlotho on autophagy in intact animals have not been described. We showed that autophagic activity is upregulated in Tg-Kl mice at baseline as evidenced by significant p62 reduction and mild increase in LC3-II formation compared with in WT mice. The reason for the discrepancy of changes between p62 and LC3 in Tg-Kl mice is not clear. We assume that p62 would be more sensitive compared with LC3-II formation. Another possibility is that αKlotho enhanced autophagy flux at baseline primarily through an increase autophagosome degradation rather induction of autophagosome formation. αKlotho deficiency leads to severely impaired autophagy activity at baseline, indicating that αKlotho may be a housekeeping protein for maintenance of autophagy homeostasis.

After exposure to ischemic insult, kl/+ mice with lower baseline levels of autophagic flux had more apoptosis and necrosis in the kidney compared with WT mice. Tg-Kl mice with higher baseline levels of autophagy had more autophagosomes and autolysosomes but less kidney injury than WT mice, suggesting that high baseline levels of autophagy render renoprotection against ischemic injury. Our cell culture experiments supported this notion, because soluble αKlotho increased autophagic flux and alleviated H2O2-induced cytotoxicity. The protective effect of αKlotho was abolished by autophagy inhibitors, suggesting that upregulation of autophagy may be one of the mechanisms of αKlotho cytoprotection. We proposed that decrease in αKlotho because of high-phosphate challenge, kidney disease, or aging renders the kidney more vulnerable to ischemic injury. More in vivo work is needed to confirm whether αKlotho protects the kidney against ischemic injury through upregulation of autophagy and delineate how αKlotho regulates autophagy.

Autophagy was shown to accelerate collagen degradation induced by TGF-β1 without modulation of collagen synthesis.26,34,83 Given that αKlotho upregulates autophagic flux, we speculate that the inhibition of renal fibrosis by αKlotho may also be associated with the modulation of autophagy. Our in vitro studies support this notion, because induction of autophagy reduced collagen accumulation, and the αKlotho-induced decrease in Col I in cultured kidney cells was partially blunted by inhibitors of autophagic flux, indicating that autophagy participates in clearance of overproduced collagen driven by a constitutively active promoter. It is important to note that our study does not exclude other possibilities through which αKlotho suppresses renal fibrosis, such as transcriptional or post-translational inhibition of Col I production. Whether αKlotho reduces renal fibrosis post-IRI by modulation of autophagy activity remains to be confirmed with in vivo experiment.

In conclusion, animals surviving from AKI still progress to CKD if the initial renal insult is adequately severe. αKlotho deficiency and high-phosphate challenge accelerate AKI to CKD progression. αKlotho supplementation prevents this progression by promoting AKI recovery and attenuating renal fibrosis. The renoprotective and antifibrotic effects of αKlotho are probably, at least in part, attributable to an increase in autophagic flux (Figure 9D). Obviously, αKlotho also protects the kidney through antioxidative17,55,84 and antiapoptotic effects.17,55,85 Consequently, less kidney damage should lead to less renal fibrosis. Administration of αKlotho protein may be a promising strategy to prevent or retard CKD progression post-AKI.

Concise Methods

Antibodies and Chemicals

Details are shown in Supplemental Material.

Animal Models and Experiments

Genetic αKlotho hypomorphic mice with αKlotho deficiency (kl/kl or kl/+) and transgenic mice overexpressing αKlotho (Tg-Kl) were previously described.5,86 All were 129 S1/SVlmJ (129 SV) background. A transgenic reporter mouse with GFP-LC364 was a gift from Noboru Mizushima (Tokyo Medical and Dental University), and a second transgenic reporter mouse62,65 with RFP;GFP-LC3 was a gift from Joseph Hill (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center). These lines were crossmated with WT mice 129 S1/SVlmJ (129 SV) for approximately five generations and subjected to the experimental surgeries. The RFP;GFP-LC3 reporter mouse line was also crossmated with kl/+, WT, and Tg-Kl mouse lines to generate three new mouse lines: kl/+;RFP;GFP-LC3, WT;RFP;GFP-LC3, and Tg-Kl;RFP;GFP-LC3, respectively.

Most experiments were performed in 3-month-old mice unless specifically stated. Two AKI models were generated using established methods from our laboratory15,18: (1) Bi-IRI,15 and (2) Npx-IRI.18 To explore the effects of high-phosphate diet, we started to treat animals 2 weeks after the acute insult with rodent chow (2.0% Pi; Harlan Teklad TD-08020; Harlan Industries, Indianapolis, IN) versus normal rodent chows (0.7% Pi; Harlan Teklad) for 18 weeks. All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Detailed information is in Supplemental Material.

Blood, Urine, and Kidney Samples Collection

At designated time points, mice were placed individually in metabolic cages (Hatteras Instruments Inc., Cary, NC) for 24-hour urine collections. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane; blood samples were collected in heparinized tubes, and plasma was separated and stored at −80°C until analysis. Urinary and plasma chemistries measurements used previously published methods.87 For histology, kidneys were isolated, sliced, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin blocks for histologic and immunohistochemical studies; the remaining parts of kidneys were snap frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C until RNA or protein extraction.

Kidney Histology and Histopathology, Immunohistochemistry, Immunoblotting, and Real–Time RT-PCR

Four-micrometer sections of paraffin–embedded kidney tissues were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, Masson Trichrome, and periodic acid–Schiff. A semiquantitative pathologic scoring system was used as described.18 To evaluate renal fibrosis, the fibrotic area and fibrosis intensity in Trichrome–stained kidney sections were quantified with the ImageJ program with published methods in a manner blinded to experimental conditions.87 Immunohistochemical studies and immunoblotting were performed as previously described.15,17,18 Detailed information about primary and secondary antibodies is in Supplemental Material.

Total RNA from the kidney was extracted using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). cDNA was generated with oligo-dT primers using the SuperScript III First Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Primers used for qPCR and its conditions are shown in Supplemental Material. Data were expressed at an amplification number of 2−ΔΔCt normalized to cyclophilin and compared with controls.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

The kidney slices were fixed overnight with Karnovsky fixative (2.5% glutaraldehyde, 4% paraformaldehyde, and 8 mM CaCl2 in cacodylate buffer [0.1 M, pH 7.4]). Ultrathin sections were visualized with a Jeol 1200 EX Transmission Electron Microscope (Jeol Ltd., Akishima, Japan) in a manner blinded to experimental conditions.

Cell Culture

The working concentration of Baf was 200 nM, the working concentration of LiCl was 10 mM, the working concentration of rapamycin was 0.5 μM, the working concentration of wortmannin was 10 μM, and the working concentration of 3-MA was 10 mM. The LDH release kit was purchased from a vendor (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA).

The GFP-LC3 fusion plasmid was transiently transfected into OK cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). OK cells were treated with H2O2 and/or autophagy modulators (inducers or suppressors) in the presence or absence of αKlotho protein. Cell lysates were prepared16,17 and immunoblotted for LC3 protein. Supernatants from cell culture media were used for measurement of LDH release as we described previously.16,17 Fluorescent microscopy was performed as described previously.17,88 The number of punctae was quantified under confocal microscopy using at least 100 cells per sample.

In addition, a CMV-GFP-Col I α2 (GFP-Col I) plasmid (OriGene Technologies, Rockville, MD) was transiently transfected into OK cells. After treatment with autophagy modulators or αKlotho, cells were fixed, stained with anti-αKlotho, counterstained with rhodamine-phalloidin, and subjected to confocal fluorescent microscopy. Cells were then stained with Sirius Red/Fast Green Collagen Staining Kit (Chondrex, Inc., Redmond, WA) for quantitative analysis collagen accumulation in cells following the kit’s instructions.

Statistical Analyses

Data are expressed as means±SDs. Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired t test or one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Newman–Keuls test when applicable. A P value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Additional information about materials and methods is in Supplemental Material.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Makoto Kuro-o for continuous helpful discussions and provision of reagents. The authors thank Dr. Noboru Mizushima (Tokyo Medical and Dental University) for providing the transgenic GFP-LC3 reporter mouse and the GFP-LC3 plasmid and Dr. Joseph Hill (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center) for providing the transgenic RFP;GFP-LC3 reporter mouse. The authors also thank Ms. Jean Paek and Ms. Jessica Lucas for technical assistance.

The authors were, in part, supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-DK091392 and R01-DK092461, George M. O’Brien Kidney Research Center Grant P30-DK-07938, the Simmons Family Foundation, the Pak Center Innovative Research Support Program, and the Pak-Seldin Center for Metabolic and Clinical Research.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2015060613/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ali T, Khan I, Simpson W, Prescott G, Townend J, Smith W, Macleod A: Incidence and outcomes in acute kidney injury: A comprehensive population-based study. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1292–1298, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grams ME, Estrella MM, Coresh J, Brower RG, Liu KD National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network : Fluid balance, diuretic use, and mortality in acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 966–973, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bucaloiu ID, Kirchner HL, Norfolk ER, Hartle JE 2nd, Perkins RM: Increased risk of death and de novo chronic kidney disease following reversible acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 81: 477–485, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu VC, Wu CH, Huang TM, Wang CY, Lai CF, Shiao CC, Chang CH, Lin SL, Chen YY, Chen YM, Chu TS, Chiang WC, Wu KD, Tsai PR, Chen L, Ko WJ NSARF Group : Long-term risk of coronary events after AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 595–605, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Kawaguchi H, Suga T, Utsugi T, Ohyama Y, Kurabayashi M, Kaname T, Kume E, Iwasaki H, Iida A, Shiraki-Iida T, Nishikawa S, Nagai R, Nabeshima YI: Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature 390: 45–51, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki M, Uehara Y, Motomura-Matsuzaka K, Oki J, Koyama Y, Kimura M, Asada M, Komi-Kuramochi A, Oka S, Imamura T: betaKlotho is required for fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 21 signaling through FGF receptor (FGFR) 1c and FGFR3c. Mol Endocrinol 22: 1006–1014, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ito S, Fujimori T, Hayashizaki Y, Nabeshima Y: Identification of a novel mouse membrane-bound family 1 glycosidase-like protein, which carries an atypical active site structure. Biochim Bkiophys Acta 1576: 341–345, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li SA, Watanabe M, Yamada H, Nagai A, Kinuta M, Takei K: Immunohistochemical localization of Klotho protein in brain, kidney, and reproductive organs of mice. Cell Struct Funct 29: 91–99, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imura A, Iwano A, Tohyama O, Tsuji Y, Nozaki K, Hashimoto N, Fujimori T, Nabeshima Y: Secreted Klotho protein in sera and CSF: Implication for post-translational cleavage in release of Klotho protein from cell membrane. FEBS Lett 565: 143–147, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bloch L, Sineshchekova O, Reichenbach D, Reiss K, Saftig P, Kuro-o M, Kaether C: Klotho is a substrate for alpha-, beta- and gamma-secretase. FEBS Lett 583: 3221–3224, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen CD, Tung TY, Liang J, Zeldich E, Tucker Zhou TB, Turk BE, Abraham CR: Identification of cleavage sites leading to the shed form of the anti-aging protein klotho. Biochemistry 53: 5579–5587, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu MC, Shi M, Zhang J, Addo T, Cho HJ, Barker SL, Ravikumar P, Gillings N, Bian A, Sidhu SS, Kuro-o M, Moe OW: Renal production, uptake, and handling of circulating αKlotho [published online ahead of print May 14, 2015]. J Am Soc Nephrol doi:ASN.2014101030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu MC, Shiizaki K, Kuro-o M, Moe OW: Fibroblast growth factor 23 and Klotho: Physiology and pathophysiology of an endocrine network of mineral metabolism. Annu Rev Physiol 75: 503–533, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu MC, Kuro-o M, Moe OW: The emerging role of Klotho in clinical nephrology. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 2650–2657, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu MC, Shi M, Zhang J, Quiñones H, Griffith C, Kuro-o M, Moe OW: Klotho deficiency causes vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 124–136, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu MC, Shi M, Cho HJ, Zhang J, Pavlenco A, Liu S, Sidhu S, Huang LJ, Moe OW: The erythropoietin receptor is a downstream effector of Klotho-induced cytoprotection. Kidney Int 84: 468–481, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panesso MC, Shi M, Cho HJ, Paek J, Ye J, Moe OW, Hu MC: Klotho has dual protective effects on cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 85: 855–870, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu MC, Shi M, Zhang J, Quiñones H, Kuro-o M, Moe OW: Klotho deficiency is an early biomarker of renal ischemia-reperfusion injury and its replacement is protective. Kidney Int 78: 1240–1251, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugiura H, Yoshida T, Shiohira S, Kohei J, Mitobe M, Kurosu H, Kuro-o M, Nitta K, Tsuchiya K: Reduced Klotho expression level in kidney aggravates renal interstitial fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 302: F1252–F1264, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doi S, Zou Y, Togao O, Pastor JV, John GB, Wang L, Shiizaki K, Gotschall R, Schiavi S, Yorioka N, Takahashi M, Boothman DA, Kuro-o M: Klotho inhibits transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-beta1) signaling and suppresses renal fibrosis and cancer metastasis in mice. J Biol Chem 286: 8655–8665, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pavik I, Jaeger P, Ebner L, Wagner CA, Petzold K, Spichtig D, Poster D, Wüthrich RP, Russmann S, Serra AL: Secreted Klotho and FGF23 in chronic kidney disease Stage 1 to 5: A sequence suggested from a cross-sectional study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 352–359, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim HR, Nam BY, Kim DW, Kang MW, Han JH, Lee MJ, Shin DH, Doh FM, Koo HM, Ko KI, Kim CH, Oh HJ, Yoo TH, Kang SW, Han DS, Han SH: Circulating α-klotho levels in CKD and relationship to progression. Am J Kidney Dis 61: 899–909, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levine B, Kroemer G: Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell 132: 27–42, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mizushima N, Komatsu M: Autophagy: Renovation of cells and tissues. Cell 147: 728–741, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi AM, Ryter SW, Levine B: Autophagy in human health and disease. N Engl J Med 368: 651–662, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He L, Livingston MJ, Dong Z: Autophagy in acute kidney injury and repair. Nephron Clin Pract 127: 56–60, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang M, Wei Q, Dong G, Komatsu M, Su Y, Dong Z: Autophagy in proximal tubules protects against acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 82: 1271–1283, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishihara M, Urushido M, Hamada K, Matsumoto T, Shimamura Y, Ogata K, Inoue K, Taniguchi Y, Horino T, Fujieda M, Fujimoto S, Terada Y: Sestrin-2 and BNIP3 regulate autophagy and mitophagy in renal tubular cells in acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 305: F495–F509, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaushal GP: Autophagy protects proximal tubular cells from injury and apoptosis. Kidney Int 82: 1250–1253, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Periyasamy-Thandavan S, Jiang M, Wei Q, Smith R, Yin XM, Dong Z: Autophagy is cytoprotective during cisplatin injury of renal proximal tubular cells. Kidney Int 74: 631–640, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takahashi A, Kimura T, Takabatake Y, Namba T, Kaimori J, Kitamura H, Matsui I, Niimura F, Matsusaka T, Fujita N, Yoshimori T, Isaka Y, Rakugi H: Autophagy guards against cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Am J Pathol 180: 517–525, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kimura T, Takabatake Y, Takahashi A, Kaimori JY, Matsui I, Namba T, Kitamura H, Niimura F, Matsusaka T, Soga T, Rakugi H, Isaka Y: Autophagy protects the proximal tubule from degeneration and acute ischemic injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 902–913, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Isaka Y, Kimura T, Takabatake Y: The protective role of autophagy against aging and acute ischemic injury in kidney proximal tubular cells. Autophagy 7: 1085–1087, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ding Y, Kim SL, Lee SY, Koo JK, Wang Z, Choi ME: Autophagy regulates TGF-β expression and suppresses kidney fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 2835–2846, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li L, Zepeda-Orozco D, Black R, Lin F: Autophagy is a component of epithelial cell fate in obstructive uropathy. Am J Pathol 176: 1767–1778, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Livingston MJ, Dong Z: Autophagy in acute kidney injury. Semin Nephrol 34: 17–26, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng H, Fan X, Lawson WE, Paueksakon P, Harris RC: Telomerase deficiency delays renal recovery in mice after ischemia-reperfusion injury by impairing autophagy. Kidney Int 88: 85–94, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubinsztein DC, Mariño G, Kroemer G: Autophagy and aging. Cell 146: 682–695, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cuervo AM, Bergamini E, Brunk UT, Dröge W, Ffrench M, Terman A: Autophagy and aging: The importance of maintaining “clean” cells. Autophagy 1: 131–140, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Green DR, Levine B: To be or not to be? How selective autophagy and cell death govern cell fate. Cell 157: 65–75, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin Y, Sun Z: In vivo pancreatic β-cell-specific expression of antiaging gene Klotho: A novel approach for preserving β-cells in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 64: 1444–1458, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iida RH, Kanko S, Suga T, Morito M, Yamane A: Autophagic-lysosomal pathway functions in the masseter and tongue muscles in the klotho mouse, a mouse model for aging. Mol Cell Biochem 348: 89–98, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shiozaki M, Yoshimura K, Shibata M, Koike M, Matsuura N, Uchiyama Y, Gotow T: Morphological and biochemical signs of age-related neurodegenerative changes in klotho mutant mice. Neuroscience 152: 924–941, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shu G, Xie B, Ren F, Liu DC, Zhou J, Li Q, Chen J, Yuan L, Zhou J: Restoration of klotho expression induces apoptosis and autophagy in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 36: 121–129, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Polichnowski AJ, Lan R, Geng H, Griffin KA, Venkatachalam MA, Bidani AK: Severe renal mass reduction impairs recovery and promotes fibrosis after AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 1496–1507, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wynn TA, Ramalingam TR: Mechanisms of fibrosis: Therapeutic translation for fibrotic disease. Nat Med 18: 1028–1040, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zeisberg M, Neilson EG: Mechanisms of tubulointerstitial fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1819–1834, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu MC, Shi M, Cho HJ, Adams-Huet B, Paek J, Hill K, Shelton J, Amaral AP, Faul C, Taniguchi M, Wolf M, Brand M, Takahashi M, Kuro-O M, Hill JA, Moe OW: Klotho and phosphate are modulators of pathologic uremic cardiac remodeling. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 1290–1302, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kestenbaum B, Sampson JN, Rudser KD, Patterson DJ, Seliger SL, Young B, Sherrard DJ, Andress DL: Serum phosphate levels and mortality risk among people with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 520–528, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Drüeke TB, Massy ZA: Phosphate binders in CKD: Bad news or good news? J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1277–1280, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hallan SI, Ritz E, Lydersen S, Romundstad S, Kvenild K, Orth SR: Combining GFR and albuminuria to classify CKD improves prediction of ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1069–1077, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lau WL, Leaf EM, Hu MC, Takeno MM, Kuro-o M, Moe OW, Giachelli CM: Vitamin D receptor agonists increase klotho and osteopontin while decreasing aortic calcification in mice with chronic kidney disease fed a high phosphate diet. Kidney Int 82: 1261–1270, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koh N, Fujimori T, Nishiguchi S, Tamori A, Shiomi S, Nakatani T, Sugimura K, Kishimoto T, Kinoshita S, Kuroki T, Nabeshima Y: Severely reduced production of klotho in human chronic renal failure kidney. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 280: 1015–1020, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sakan H, Nakatani K, Asai O, Imura A, Tanaka T, Yoshimoto S, Iwamoto N, Kurumatani N, Iwano M, Nabeshima Y, Konishi N, Saito Y: Reduced renal α-Klotho expression in CKD patients and its effect on renal phosphate handling and vitamin D metabolism. PLoS One 9: e86301, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sugiura H, Yoshida T, Tsuchiya K, Mitobe M, Nishimura S, Shirota S, Akiba T, Nihei H: Klotho reduces apoptosis in experimental ischaemic acute renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 2636–2645, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ma D, Lim T, Xu J, Tang H, Wan Y, Zhao H, Hossain M, Maxwell PH, Maze M: Xenon preconditioning protects against renal ischemic-reperfusion injury via HIF-1alpha activation. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 713–720, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weidemann A, Bernhardt WM, Klanke B, Daniel C, Buchholz B, Câmpean V, Amann K, Warnecke C, Wiesener MS, Eckardt KU, Willam C: HIF activation protects from acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 486–494, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamada S, Tokumoto M, Tatsumoto N, Taniguchi M, Noguchi H, Nakano T, Masutani K, Ooboshi H, Tsuruya K, Kitazono T: Phosphate overload directly induces systemic inflammation and malnutrition as well as vascular calcification in uremia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F1418–F1428, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kendrick J, Chonchol M: The role of phosphorus in the development and progression of vascular calcification. Am J Kidney Dis 58: 826–834, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shroff R: Phosphate is a vascular toxin. Pediatr Nephrol 28: 583–593, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kimura A, Ishida Y, Inagaki M, Nakamura Y, Sanke T, Mukaida N, Kondo T: Interferon-γ is protective in cisplatin-induced renal injury by enhancing autophagic flux. Kidney Int 82: 1093–1104, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li L, Wang ZV, Hill JA, Lin F: New autophagy reporter mice reveal dynamics of proximal tubular autophagy. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 305–315, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Klionsky DJ, Abdalla FC, Abeliovich H, Abraham RT, Acevedo-Arozena A, Adeli K, Agholme L, Agnello M, Agostinis P, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, et al.: Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy 8: 445–544, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mizushima N: Methods for monitoring autophagy using GFP-LC3 transgenic mice. Methods Enzymol 452: 13–23, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin F, Wang ZV, Hill JA: Seeing is believing: Dynamic changes in renal epithelial autophagy during injury and repair. Autophagy 10: 691–693, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hsiao HW, Tsai KL, Wang LF, Chen YH, Chiang PC, Chuang SM, Hsu C: The decline of autophagy contributes to proximal tubular dysfunction during sepsis. Shock 37: 289–296, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mariño G, Niso-Santano M, Baehrecke EH, Kroemer G: Self-consumption: The interplay of autophagy and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15: 81–94, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vakifahmetoglu-Norberg H, Xia HG, Yuan J: Pharmacologic agents targeting autophagy. J Clin Invest 125: 5–13, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Seglen PO, Gordon PB: 3-Methyladenine: Specific inhibitor of autophagic/lysosomal protein degradation in isolated rat hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 79: 1889–1892, 1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hsu CY, Ordoñez JD, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Go AS: The risk of acute renal failure in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 74: 101–107, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Heyman SN, Lieberthal W, Rogiers P, Bonventre JV: Animal models of acute tubular necrosis. Curr Opin Crit Care 8: 526–534, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ibels LS, Alfrey AC, Haut L, Huffer WE: Preservation of function in experimental renal disease by dietary restriction of phosphate. N Engl J Med 298: 122–126, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Haut LL, Alfrey AC, Guggenheim S, Buddington B, Schrier N: Renal toxicity of phosphate in rats. Kidney Int 17: 722–731, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Alfrey AC, Karlinsky M, Haut L: Protective effect of phosphate restriction on renal function. Adv Exp Med Biol 128: 209–218, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Giachelli CM, Jono S, Shioi A, Nishizawa Y, Mori K, Morii H: Vascular calcification and inorganic phosphate. Am J Kidney Dis 38[Suppl 1]: S34–S37, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Alfrey AC, Ibels LS: Role of phosphate and pyrophosphate in soft tissue calcification. Adv Exp Med Biol 103: 187–193, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Neves KR, Graciolli FG, dos Reis LM, Pasqualucci CA, Moysés RM, Jorgetti V: Adverse effects of hyperphosphatemia on myocardial hypertrophy, renal function, and bone in rats with renal failure. Kidney Int 66: 2237–2244, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Satoh M, Nagasu H, Morita Y, Yamaguchi TP, Kanwar YS, Kashihara N: Klotho protects against mouse renal fibrosis by inhibiting Wnt signaling. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303: F1641–F1651, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhou L, Li Y, Zhou D, Tan RJ, Liu Y: Loss of Klotho contributes to kidney injury by derepression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 771–785, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Eren M, Boe AE, Murphy SB, Place AT, Nagpal V, Morales-Nebreda L, Urich D, Quaggin SE, Budinger GR, Mutlu GM, Miyata T, Vaughan DE: PAI-1-regulated extracellular proteolysis governs senescence and survival in Klotho mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: 7090–7095, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Takeshita K, Yamamoto K, Ito M, Kondo T, Matsushita T, Hirai M, Kojima T, Nishimura M, Nabeshima Y, Loskutoff DJ, Saito H, Murohara T: Increased expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 with fibrin deposition in a murine model of aging, “Klotho” mouse. Semin Thromb Hemost 28: 545–554, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Xie B, Zhou J, Shu G, Liu DC, Zhou J, Chen J, Yuan L: Restoration of klotho gene expression induces apoptosis and autophagy in gastric cancer cells: Tumor suppressive role of klotho in gastric cancer. Cancer Cell Int 13: 18, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kim SI, Na HJ, Ding Y, Wang Z, Lee SJ, Choi ME: Autophagy promotes intracellular degradation of type I collagen induced by transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1. J Biol Chem 287: 11677–11688, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rakugi H, Matsukawa N, Ishikawa K, Yang J, Imai M, Ikushima M, Maekawa Y, Kida I, Miyazaki J, Ogihara T: Anti-oxidative effect of Klotho on endothelial cells through cAMP activation. Endocrine 31: 82–87, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ikushima M, Rakugi H, Ishikawa K, Maekawa Y, Yamamoto K, Ohta J, Chihara Y, Kida I, Ogihara T: Anti-apoptotic and anti-senescence effects of Klotho on vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 339: 827–832, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Clark JD, Pastor JV, Nandi A, Gurnani P, McGuinness OP, Chikuda H, Yamaguchi M, Kawaguchi H, Shimomura I, Takayama Y, Herz J, Kahn CR, Rosenblatt KP, Kuro-o M: Suppression of aging in mice by the hormone Klotho. Science 309: 1829–1833, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rutkowski JM, Wang ZV, Park AS, Zhang J, Zhang D, Hu MC, Moe OW, Susztak K, Scherer PE: Adiponectin promotes functional recovery after podocyte ablation. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 268–282, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hu MC, Shi M, Zhang J, Pastor J, Nakatani T, Lanske B, Razzaque MS, Rosenblatt KP, Baum MG, Kuro-o M, Moe OW: Klotho: A novel phosphaturic substance acting as an autocrine enzyme in the renal proximal tubule. FASEB J 24: 3438–3450, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.