Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET) for estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer remains suboptimal, which suggests that women are not getting the full benefit of the treatment to reduce breast cancer recurrence and mortality. The majority of studies on adherence to AET focus on identifying factors among those women at the highest levels of adherence and provide little insight on factors that influence medication use across the distribution of adherence.

OBJECTIVE:

To understand how factors influence adherence among women across low and high levels of adherence.

METHODS:

A retrospective evaluation was conducted using the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database from 2007-2011. Privately insured women aged 18-64 years who were recently diagnosed and treated for breast cancer and who initiated AET within 12 months of primary treatment were assessed. Adherence was measured as the proportion of days covered (PDC) over a 12-month period. Simultaneous multivariable quantile regression was used to assess the association between treatment and demographic factors, use of mail order pharmacies, medication switching, and out-of-pocket costs and adherence. The effect of each variable was examined at the 40th, 60th, 80th, and 95th quantiles.

RESULTS:

Among the 6,863 women in the cohort, mail order pharmacies had the greatest influence on adherence at the 40th quantile, associated with a 29.6% (95% CI = 22.2-37.0) higher PDC compared with retail pharmacies. Out-of-pocket cost for a 30-day supply of AET greater than $20 was associated with an 8.6% (95% CI = 2.8-14.4) lower PDC versus $0-$9.99. The main factors that influenced adherence at the 95th quantile were mail order pharmacies, associated with a 4.4% higher PDC (95% CI = 3.8-5.0) versus retail pharmacies, and switching AET medication 2 or more times, associated with a 5.6% lower PDC versus not switching (95% CI = 2.3-9.0).

CONCLUSIONS:

Factors associated with adherence differed across quantiles. Addressing the use of mail order pharmacies and out-of-pocket costs for AET may have the greatest influence on improving adherence among those women with low adherence.

What is already known about this subject

Adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET) is effective at reducing the risk of recurrence and the rate of mortality for women diagnosed with estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer, but adherence to this therapy remains suboptimal.

Factors associated with AET adherence include out-of-pocket costs for medication, use of mail order or retail pharmacies, and the number of times patients switch AET medications.

What this study adds

This study found that factors associated with adherence vary across the range of adherence levels.

The use of mail order pharmacies and 30-day out-of-pocket costs for AET medication influenced adherence differently at low-, moderately low-, and high-adherence levels among a group of privately insured patients.

Allowing patients to fill AET medication using mail order pharmacies or eliminating out-of-pocket costs for AET medication may improve adherence to this effective treatment, particularly among those patients with low adherence.

Estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer is diagnosed in two thirds of all breast cancer cases in the United States.1 At a minimum, 5 years of adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET) is the standard of care for women with ER+ early-stage breast cancer; however, studies suggest that women who remain in treatment for 10 years or more may continue to experience benefits.2 Treatment with tamoxifen is recommended for premenopausal women, whereas postmenopausal women may be initially treated with tamoxifen followed by an aromatase inhibitor, such as letrozole, anastrozole, or exemestane, or may begin treatment with an aromatase inhibitor.

Treatment with AET has been shown to reduce the rate of cancer recurrence by 39% and reduce breast cancer mortality by about one third, compared with nonusers.3 Despite clear evidence of the benefits of treatment, however, adherence to recommended treatment over a 12-month period is suboptimal and ranges from 31% to 81%.4,5

Policies and interventions that address factors most influential at low levels of adherence will have the most impact at improving breast cancer outcomes among the most vulnerable group of survivors. Studies reveal that two thirds of breast cancer patients who initiate AET therapy are adherent; therefore, conclusions have been drawn regarding the association with factors among the highest adhering of the population.4,6-8 Such studies show that factors associated with medication adherence to AET are out-of-pocket costs for medication,6-9 use of mail order or retail pharmacies,7,8 and the number of times AET medication is switched in a 12-month period.8 Little evidence exists for determining the influence of these factors at low levels of adherence.

Quantile regression methods provide a complete picture of the patterns of adherence among low adherers, who often represent a smaller yet important proportion of study cohorts in the medication adherence literature.10-12 Quantile regression has been used to study the association of factors affecting low adherers taking antihypertensive, antidiabetic, and anti-inflammatory medications.10-12 Studies using logistic regression methods use a binary variable of adherence (medication possession ratio [MPR] ≥ 80%), and factors may influence adherence differently at low- and high-adherence levels rather than at the commonly used cutpoint of 80%.7-9,13 In addition, conducting an ordinary least squares regression with a continuous measure of adherence provides evidence of how the average adherence in the study cohort varies with each factor, which is strongly influenced by patients with high use and does not allow us to make inferences among patients with low medication use. Quantile regression methods offer the best statistical method to examine the influence of factors at low levels of adherence to AET.

The purpose of this study was to apply a quantile regression method using prescription claims and encounter data to examine how factors affect adherence to AET drugs across levels of adherence among privately insured women treated for newly diagnosed breast cancer.

Methods

Data Source

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using prescription claims and encounter data from a nationwide, commercially insured patient population in the United States. The Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database contains medical utilization and expenditures across inpatient, outpatient, and prescription claims. All data were de-identified in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act requirements. Follow-up data were available through December 31, 2011. The study was deemed not human subjects research because the data for the study were publicly available and were de-identified.

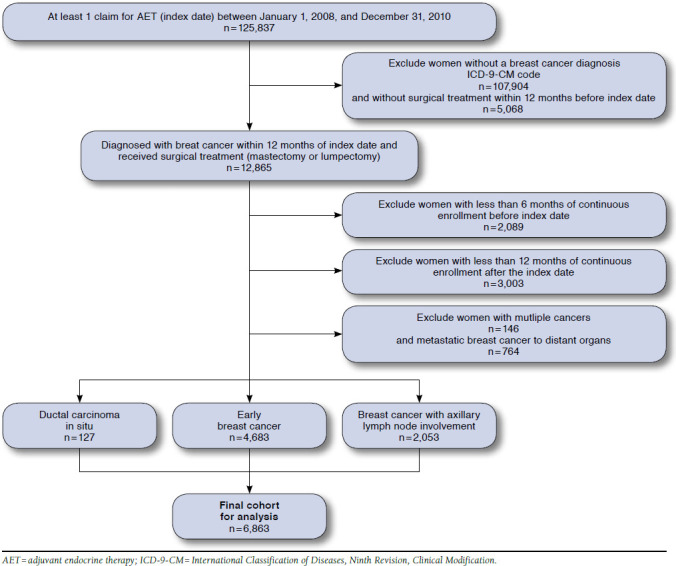

Sample Selection

Women in the database were identified who were aged < 64 years and had at least 1 prescription claim for an aromatase inhibitor (anastrozole, letrozole, and exemestane) or tamoxifen between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2010. Data were available beginning January 1, 2007, through December 31, 2011, which allowed the capture of baseline characteristics and 12 months of continuous follow-up (Figure 1). AET initiation was defined as no evidence of an AET prescription for at least 6 months before the first claim (index claim). Women were included if they were diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 233.0), primary invasive breast cancer with or without axillary lymph node involvement (ICD-9-CM codes 174.0-174.9 with or without 196.0-196.3, 196.5-196.6, or 196.8-196.9), and had been surgically treated with bilateral mastectomy, mastectomy, or breast conserving surgery/lumpectomy within 12 months before the index claim.14-16 Study inclusion was limited to women continuously enrolled in a health plan with prescription drug coverage for at least 6 months before and 12 months after the index claim. Women were excluded if they had multiple primary cancers or metastatic breast cancer to distant organs any time during the study period.

FIGURE 1.

Study Cohort Selection and Subject Exclusion

Outcome

The primary outcome was medication adherence to AET, which was defined as the proportion of days covered (PDC). PDC was calculated based on the fill dates and the number of days supply for AET prescription in a 12-month study period.17,18 The numerator was the number of days covered by the prescription fill, and days were adjusted so that women could not have overlapping days of coverage. We assumed that women did not take the refilled endocrine therapy before exhausting the previous prescription.19 The denominator was 365 days. The ratio was multiplied by 100 to obtain a percentage of the proportion of days covered.

Study Variables

Age was calculated at the index date and evaluated as a categorical variable similar to other studies.6-8 The Elixhauser Comorbidity Index was used for all inpatient and outpatient diagnoses (ICD-9-CM) during the time period before the index date.20 Medication burden was calculated as the count of unique drug classes filled 90 days before the index date. We included data for the Northeast, North Central, South, and West U.S. geographic regions.

Initial breast cancer treatments were identified using ICD-9-CM and Current Procedural Terminology codes from inpatient claims to identify whether patients had a mastectomy, bilateral mastectomy, or a breast conserving surgery/lumpectomy (Table 1). Similarly, patients were identified as having had completed chemotherapy and/or radiation before the index date (Table 1).14-16 A categorical variable was included for the duration of time from surgical treatment to the index date (0-3, 4-6, 7-9, and 10-12 months).

TABLE 1.

Procedural (ICD-9-CM and CPT) Codes for Treatment of Breast Cancer

| Procedure | Identification Code |

|---|---|

| Surgical procedures | |

| Mastectomy | ICD-9-CM: 85.33-85.35, 85.41, 85.43, 85.45, 85.47 |

| CPT: 19303-19307, 19180, 19182, 19200, 19220, 19240, 88309 | |

| Bilateral mastectomy lumpectomy/breast conserving surgery | ICD-9-CM: 85.42, 85.44, 85.46, 85.48 |

| ICD-9-CM: 85.20-85.23 | |

| CPT: 19120-19126, 88307, 19160, 19162, 19301, 19302 | |

| Oophorectomy | ICD-9-CM: 65.31, 65.39, 65.41, 65.49, 65.51-65.53, 65.61-65.64 |

| CPT: 58920, 58940, 58943, 58953, 58954, 58956 | |

| Radiation | ICD-9-CM: 92.20-92.29, V58.0, V66.1, V67.1, |

| CPT: 77261-77525, 77750-77799, 19296-19298 | |

| Chemotherapy | ICD-9-CM: 99.25, V58.1, V66.2, V67.2 |

| CPT: 96400-96549, J9000-J9999, Q0083-Q0085 | |

CPT = Current Procedural Terminology; ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification.

Out-of-pocket costs were calculated for AET medications by summing together coinsurance, deductibles, and copayments associated with AET pharmacy claims. AET costs were standardized to 30-day amounts when prescriptions were for longer periods and categorized as $0-$9.99, $10.00-$19.99, or > $20.00. The average 30-day standardized out-of-pocket costs were also calculated for all other health care expenses that occurred between prescription refills until the patient no longer had AET medication on hand and categorized as < $49.99, $50-99.99, $100-149.99, $150-199.99, and > $200.

Patients were categorized into 3 groups based on the type of pharmacy used during the follow-up period: retail pharmacies only, mail order pharmacies only, or at least 1 mail order and 1 retail pharmacy. We calculated the number of times a patient switched AET medication if they filled a prescription for any aromatase inhibitor or tamoxifen that differed from the index medication and categorized as not switched, switched once, or switched 2 or more times. A categorical variable was also included for health plan type: health maintenance organization, preferred provider organization, or other.

Statistical Analysis

The frequencies for each study variable were calculated based on the proportion of women with (a) less than or equal to 146 days of medication coverage, (b) between 146 and 346 days of medication coverage, and (c) greater than 346 days of coverage.

We chose these categories to most appropriately group women with different levels of adherence from very low adherence to fully adherent into meaningfully sized groups. Unadjusted differences were evaluated across patient groups using the Pearson chi-square test for categorical variables.

A simultaneous multivariable quantile regression model was used to examine the differential effects of each independent variable on the conditional quantile of adherence.21 The STATA ‘sqreg’ command with 1,000 bootstrap replications was used to estimate the standard errors, which is analogous to robust standard error estimates in linear regression.22 In the quantile regression, we regressed specific quantiles of PDC, the dependent variable, on each variable described.21 One quantile regression was used with 4 simultaneous models, where the cutoff values for the quantiles referred to the unconditional and clinically meaningful PDC values Q1 = 0.40, Q2 = 0.60, Q3 = 0.80, and Q4 = 0.95, which correspond to the 8th, 15th, 26th, and 54th percentiles of the distribution of PDC. Since the objective of this exploratory study was to examine how factors influence adherence among women across low and high levels of adherence, we selected the clinically meaningful cutoff value of PDC = 0.80 and 2 values lower than 0.80 (PDC = 0.40 and 0.60) and a value greater (PDC = 0.95). These values correspond to similar cutpoints used by other authors when studying adherence using quantile regression methods.10 Quantile regression predicts the effect of each independent variable at the conditional quantile rather than the mean.21 For comparison purposes, we used a multivariable regression model using ordinary least squares and robust standard error estimates to determine the association between each of the covariates and the mean adherence (PDC).

Multiple models of the data were constructed; therefore, we could reject the null hypothesis at the 0.01 level of statistical significance.21 All analyses were conducted using Stata 13.1 SE (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

A total of 6,863 women were aged 18-64 years and initiated AET following a diagnosis and surgical treatment of breast cancer. Characteristics of the study cohort across a range of days of medication coverage are shown in Table 2. Approximately 8% of the cohort had less than 146 days of medication coverage in the 12-month study period and were considered low adherers, whereas 47.6% of the cohort had greater than 347 days of medication coverage and were considered high adherers. The proportion of women with days of medication covered differed significantly on a number of demographic, clinical, treatment, and cost variables. Women with less than 146 days of medication coverage compared with women with greater than 347 days of medication coverage tended to be aged < 49 years (47.3% vs. 36.4%), had not received chemotherapy (46.9% vs. 56.3%), had not switched medication (15.1% vs. 11.6%), and received care in the southern United States (45.1% vs. 36.5%). A greater proportion of high-adhering women compared with low-adhering women (< 146 days of medication coverage) had mean out-of-pocket costs for 30 days supply of AET between $0-$9.99 (51.4% vs. 44.0%) and had used mail order pharmacies to fill AET prescriptions (20.2% vs. 2.9%).

TABLE 2.

Sample Characteristics Across Range of Adherence, Proportion of AET Medication Days Covered in a 365-Day Period (N = 6,863)

| < 146 Days Covered | 146-347 Days Covered | > 347 Days Covered | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall, % (n) | 8.0 (548) | 44.4 (3,047) | 47.6 (3,268) | |

| Breast cancer stage, % | < 0.01 | |||

| DCIS | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.8 | |

| Early stage | 75.4 | 67.3 | 67.9 | |

| Axillary lymph node involvement | 22.6 | 30.8 | 30.3 | |

| Age, years, % | < 0.001 | |||

| < 40 | 11.3 | 9.6 | 6.0 | |

| 40-49 | 36.0 | 36.2 | 30.4 | |

| 50-59 | 40.0 | 39.6 | 43.1 | |

| 60-64 | 12.8 | 14.6 | 20.5 | |

| Comorbidities,b % | ||||

| Hypertension | 17.5 | 17.4 | 18.8 | 0.37 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 5.1 | 6.2 | 5.2 | 0.18 |

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | 5.1 | 5.1 | 4.5 | 0.59 |

| Hypothyroidism | 6.6 | 5.9 | 7.3 | 0.08 |

| Obesity | 6.2 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.47 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 3.7 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 0.24 |

| Deficiency anemias | 5.1 | 4.4 | 2.9 | < 0.01 |

| Depression | 5.7 | 5.1 | 3.6 | 0.01 |

| Elixhauser conditions composite, % | 0.34 | |||

| 0 | 58.2 | 61.7 | 61.8 | |

| 1 | 26.6 | 24.6 | 26.0 | |

| 2 | 9.5 | 8.5 | 7.9 | |

| 3 | 3.8 | 3.1 | 2.9 | |

| ≥ 4 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.5 | |

| Surgery, % | 0.26 | |||

| Mastectomy | 28.7 | 27.7 | 29.5 | |

| Bilateral mastectomy | 5.3 | 4.2 | 4.9 | |

| Breast conservative surgery/lumpectomy | 66.1 | 68.1 | 65.6 | |

| Time from surgical treatment to first AET fill, months, % | < 0.001 | |||

| 0-3 | 40.2 | 36.3 | 41.7 | |

| 4-6 | 27.7 | 31.6 | 30.3 | |

| 7-9 | 22.8 | 24.5 | 22.0 | |

| 10-12 | 9.3 | 7.7 | 6.0 | |

| Chemotherapy, % | 46.9 | 59.8 | 56.3 | < 0.001 |

| Radiation therapy, % | 31.9 | 34.5 | 32.9 | 0.28 |

| Oophorectomy, % | 3.3 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 0.16 |

| Health plan type, % | < 0.01 | |||

| HMO | 22.6 | 18.5 | 17.0 | |

| PPO | 60.2 | 59.5 | 60.6 | |

| Other | 17.2 | 21.9 | 22.3 | |

| Initiation year of AET, % | 0.11 | |||

| 2008 | 34.7 | 31.2 | 31.4 | |

| 2009 | 36.9 | 34.7 | 34.4 | |

| 2010 | 28.5 | 34.2 | 34.2 | |

| Region, % | < 0.001 | |||

| Northeast | 12.8 | 15.4 | 18.8 | |

| North Central | 20.3 | 19.7 | 22.3 | |

| South | 45.1 | 44.7 | 36.5 | |

| West | 20.8 | 19.4 | 21.6 | |

| Unknown | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | |

| AET drug type at index date, % | < 0.001 | |||

| Exemestane | 2.9 | 1.7 | 1.9 | |

| Anastrozole | 24.5 | 27.4 | 33.3 | |

| Letrozole | 16.4 | 17.8 | 16.3 | |

| Tamoxifen | 56.2 | 53.1 | 48.5 | |

| Number of times AET medication switched, % | < 0.001 | |||

| 0 | 84.9 | 78.8 | 88.5 | |

| 1 | 13.5 | 18.3 | 10.3 | |

| 2 or more | 1.6 | 2.9 | 1.3 | |

| Pharmacy type | < 0.001 | |||

| Retail only | 91.4 | 77.9 | 60.6 | |

| Mail order only | 5.7 | 8.8 | 19.3 | |

| Retail and mail order | 2.9 | 13.4 | 20.2 | |

| Number of prescriptions filled 90-days before index date | < 0.001 | |||

| 0 | 9.1 | 5.4 | 3.9 | |

| 1-5 | 57.7 | 55.6 | 57.8 | |

| 6-10 | 29.0 | 32.0 | 31.6 | |

| >10 | 4.2 | 7.0 | 6.8 | |

| Out-of-pocket costs for 30 days supply of AET medication, % | < 0.001 | |||

| $0-$9.99 | 44.0 | 46.4 | 51.4 | |

| $10.00-$19.99 | 28.1 | 26.8 | 23.4 | |

| ≥ $20.00 | 27.9 | 26.9 | 25.2 | |

| Other out-of-pocket costs, 30-day average,c % | 0.03 | |||

| $0-$49.99 | 24.5 | 18.2 | 18.8 | |

| $50.00-$99.99 | 20.8 | 20.3 | 21.8 | |

| $100.00-$149.99 | 13.9 | 15.1 | 15.2 | |

| $150.00-$199.99 | 11.5 | 13.5 | 13.4 | |

| ≥$200.00 | 29.5 | 33.1 | 30.9 | |

a P values correspond to the Pearson’s chi-square test of independence.

b Comorbid conditions displayed were the most prevalent of the Elixhauser conditions in the cohort.

c Other out-of-pocket costs include costs paid by the patient for inpatient, outpatient, and medication (other than AET).

AET = adjuvant endocrine therapy; DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ; HMO = health maintenance organization; PPO = preferred provider organization.

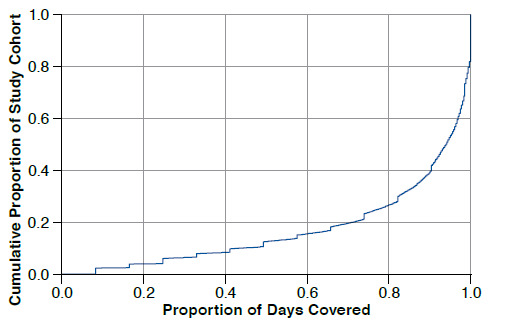

Figure 2 depicts the PDC for the cumulative proportion of the study cohort. For instance, 26% of the cohort had a PDC ≤ 0.80 or 80% and 18% of the cohort had a PDC of 100%. The mean PDC for the cohort was 83.4% (standard deviation = 24.5).

FIGURE 2.

Proportion of Medication Days Covered in the 12-Month Study Period by Cumulative Proportion of the Study Cohort (N = 6,863)

Multivariable Quantile Regression

The difference in the percentage points of adherence (PDC) at the 40th, 60th, 80th, and 95th quantiles are shown in Table 3. For comparison, the difference in the percentage points, on average, are also presented in the right hand column.

TABLE 3.

Difference in Percentage Points of PDC for AET Medication, Where Each Model Represents 40th, 60th, 80th, and 95th Percentiles of PDC, and OLS (N = 6,863)

| 40th Quantile of PDC | 60th Quantile of PDC | 80th Quantile of PDC | 95th Quantile of PDC | OLS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| βa | SE | βa | SE | βa | SE | βa | SE | βa | SE | |

| Out-of-pocket costs for 30 days supply of AET medication | ||||||||||

| $0-$9.99 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| $10.00-$19.99 | -6.8b | [0.03] | -6.7c | [0.02] | -3.3b | [0.01] | -1.0b | [ < 0.01] | -2.9c | [0.03] |

| ≥ $20.00 | -8.6c | [0.03] | -6.2b | [0.02] | -2.6b | [0.01] | -0.9b | [ < 0.01] | -3.3c | [0.03] |

| Other out-of-pocket costs for services and medication | ||||||||||

| $0-$49.99 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| $50.00-$99.99 | 4.9 | [0.30] | 2.9 | [0.03] | 0.6 | [0.01] | 0.5 | [ < 0.01] | 1.1 | [0.03] |

| $100.00-$149.99 | 3.6 | [0.40] | 1.7 | [0.03] | -0.5 | [0.01] | 0.4 | [ < 0.01] | 0.2 | [0.04] |

| $150.00-$199.99 | 4.8 | [0.04] | 1.7 | [0.03] | -0.1 | [0.02] | 0.3 | [ < 0.01] | 1.0 | [0.04] |

| ≥ $200.00 | 5.3 | [0.04] | 1.1 | [0.03] | -0.2 | [0.01] | 0.4 | [ < 0.01] | 0.7 | [0.04] |

| Breast cancer | ||||||||||

| DCIS | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Early stage | -3.2 | [0.08] | 0.8 | [0.06] | 3.9 | [0.04] | 0.9 | [0.01] | 0.7 | [0.08] |

| Axillary lymph node involvement | 3.7 | [0.08] | 4.8 | [0.06] | 6.4 | [0.04] | 1.3 | [0.01] | 2.7 | [0.08] |

| Age, years | ||||||||||

| Less than 40 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| 40-49 | 5.2 | [0.03] | 7.8b | [0.04] | 6.4b | [0.03] | 2.9c | [0.01] | 3.3c | [0.03] |

| 50-59 | 7.4b | [0.04] | 12.6c | [0.03] | 9.7c | [0.03] | 4.2c | [0.01] | 5.4c | [0.04] |

| 60-64 | 9.4b | [0.04] | 13.2c | [0.04] | 11.8c | [0.03] | 5.0c | [0.01] | 6.8c | [0.04] |

| Health plan type | ||||||||||

| HMO | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| PPO | -2.4 | [0.03] | 3.1 | [0.03] | 1.9 | [0.02] | 0.1 | [ < 0.01] | 0.5 | [0.03] |

| Other | 2.5 | [0.03] | 3.5 | [0.03] | 0.2 | [0.02] | -0.2 | [ < 0.01] | 0.1 | [0.03] |

| Initiation year of AET | ||||||||||

| 2008 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| 2009 | 1.2 | [0.03] | 2.1 | [0.02] | 0.9 | [0.01] | 0.0 | [ < 0.01] | -0.3 | [0.02] |

| 2010 | 3.1 | [0.03] | 4.8b | [0.02] | 2.3b | [0.01] | 0.1 | [ < 0.01] | 1.1 | [0.03] |

| Region | ||||||||||

| Northeast | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| North Central | -3.9 | [0.03] | -3.2 | [0.02] | -0.7 | [0.01] | -0.4 | [ < 0.01] | -1.5 | [0.03] |

| South | -5.6 | [0.03] | -6.4c | [0.02] | -3.9c | [0.01] | -1.7c | [ < 0.01] | -3.5c | [0.03] |

| West | -4.0 | [0.03] | -2.8 | [0.02] | -1.8 | [0.01] | -0.2 | [ < 0.01] | -2.2b | [0.04] |

| Unknown | -8.1 | [0.09] | -17.3 | [0.10] | -5.1 | [0.11] | -1.1 | [0.02] | -4.5 | [0.09] |

| AET drug type at index date | ||||||||||

| Exemestane | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Anastrozole | 12.6 | [0.09] | 8.0 | [0.07] | 3.0 | [0.05] | -0.3 | [0.01] | 2.9 | [0.09] |

| Letrozole | 6.5 | [0.09] | 2.0 | [0.07] | -0.3 | [0.05] | -0.9 | [0.01] | 1.3 | [0.09] |

| Tamoxifen | 5.7 | [0.09] | 4.0 | [0.07] | 1.4 | [0.05] | -0.6 | [0.01] | 0.9 | [0.09] |

| Pharmacy type | ||||||||||

| Retail only | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Mail order only | 29.6c | [0.04] | 22.6c | [0.02] | 13.5c | [0.01] | 4.4c | [ < 0.01] | 9.2c | [0.04] |

| Mail order and retail | 31.4c | [0.03] | 21.2c | [0.02] | 12.4c | [0.01] | 4.2c | [ < 0.01] | 9.8c | [0.03] |

| Number of times AET medication switched | ||||||||||

| 0 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| 1 | -3.4 | [0.02] | -8.5c | [0.02] | -10.0c | [0.02] | -4.9c | [0.01] | -4.6c | [0.02] |

| 2 or more | -2.5 | [0.05] | -10.5b | [0.05] | -10.8b | [0.04] | -5.6c | [0.02] | -5.1e | [0.05] |

| Surgery treatment | ||||||||||

| Mastectomy | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Bilateral mastectomy | -3.0 | [0.05] | 2.2 | [0.05] | 3.0 | [0.02] | 0.5 | [0.01] | 0.1 | [0.05] |

| Breast conserving surgery | -0.2 | [0.02] | 0.7 | [0.02] | -0.1 | [0.01] | -0.4 | [ < 0.01] | -0.4 | [0.02] |

| Chemotherapy | 13.6c | [0.03] | 10.9c | [0.02] | 4.9c | [0.01] | 0.7b | [ < 0.01] | 4.1b | [0.03] |

| Radiation therapy | -3.0 | [0.02] | 0.1 | [0.02] | 0.1 | [0.01] | -0.2 | [ < 0.01] | -0.3 | [0.02] |

| Oophorectomy | -2.2 | [0.07] | -3.9 | [0.07] | 0.4 | [0.04] | 0.1 | [0.01] | -1.0 | [0.07] |

| Time from surgical treatment to first AET fill, months | ||||||||||

| 0-3 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| 4-6 | -1.3 | [0.03] | -1.9 | [0.02] | -2.6b | [0.01] | -0.8 | [ < 0.01] | -2.0b | [0.03] |

| 7-9 | -5.2 | [0.03] | -3.6 | [0.02] | -3.3b | [0.01] | -1.1c | [ < 0.01] | -2.9c | [0.03] |

| 10-12 | -9.2b | [0.04] | -11.6c | [0.04] | -8.5c | [0.03] | -2.2c | [0.01] | -5.4c | [0.04] |

| Number of prescriptions filled 90 days before follow-up period | 0.5 | [ < 0.01] | 0.4 | [ < 0.01] | 0.2 | [ < 0.01] | 0.0 | [ < 0.01] | 0.2 | [ < 0.01] |

| Elixhauser conditions composite | -1.7 | [0.01] | -1.4 | [0.01] | -1.3 | [0.01] | -0.4c | [ < 0.01] | -0.8b | [0.01] |

| Intercept | 18.0 | [0.14] | 34.5c | [0.11] | 62.6c | [0.07] | 90.9c | [0.02] | 75.8c | [0.14] |

| R-squared | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.07 | |||||

a β coefficients are points of PDC.

b P < 0.05.

c P < 0.01.

AET = adjuvant endocrine therapy; DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ; HMO = health maintenance organization; OLS = ordinary least squares; PDC = proportion of days covered; PPO = preferred provider organization; SE = standard error.

Higher out-of-pocket costs for AET medication were consistently associated with lower adherence (P < 0.01). On average, women with a mean 30-day out-of-pocket cost for AET of ≥ $20.00 had an adherence to AET that was 3.3 percentage points lower than women with out-of-pocket costs for AET < $9.99, after controlling for all other variables (95% confidence interval [CI] = 4.9-1.6). However, at the 40th quantile of adherence, the influence of out-of-pocket costs for AET medication was greater, since women with out-of-pocket cost for a 30-day supply of AET at ≥ $20.00 had a PDC of 8.6 percentage points lower than women with out-of-pocket cost of < $9.99 (95% CI = 14.4-2.8). At the 95th quantile of adherence, the influence of out-of-pocket costs, although significant, was minimal (β = -0.9, 95% CI = -1.6 to -0.2).

Using mail order pharmacies to fill prescriptions for AET was significantly associated with higher adherence to AET (P < 0.01). On average, women who used only mail order pharmacies had adherence that was 9.2 percentage points higher than women who used only retail pharmacies (95% CI = 7.9-10.6). The effect of using only mail order pharmacies was even greater in the model fit to the 40th quantile (β = 29.6, 95% CI = 22.2-36.9) and was lowest at the 95th quantile (β = 4.4, 95% CI = 3.8-5.0).

On average, an increase in age significantly increased adherence to AET (P < 0.01). In the model examining the 40th quantile, age was not significantly associated with adherence. At the 95th quantile, however, women aged 60-64 years had a PDC that was 5 percentage points higher than women aged < 40 years (95% CI = 3.1-6.8) after controlling for other covariates. The effect of higher adherence with increasing age was the most influential at the 60th, 80th, and 95th quantiles (P < 0.01).

On average, women who received chemotherapy had 4.1 percentage points higher adherence than women who did not receive chemotherapy (95% CI = 2.7-5.6). Women receiving chemotherapy had significantly higher adherence compared with women who did not receive chemotherapy in the 40th, 60th, and 80th quantiles but did not in the 95th quantile (P < 0.01). Overall, the relationship among women who received chemotherapy appeared to be consistently reduced between the 40th and 95th quantiles.

We also found that in the South versus the Northwest regions of the United States, women with an increase in comorbid conditions and switching AET medication 2 or more times compared with not switching was significantly associated with lower adherence overall and in all fitted quantiles except the 40th quantile.

Discussion

This study’s findings show that predictors have a differential influence on adherence across levels of adherence. Although there were factors that were significantly associated with adherence in all fitted models, certain factors, such as out-of-pocket costs for AET, pharmacy type, and receipt of chemotherapy, had the greatest effect on adherence at the 40th quantile, whereas switching AET medication, pharmacy type, and age had the greatest effect on adherence at the 95th quantile.

The association between out-of-pocket costs for AET medication and adherence have been demonstrated in previous studies.6-9 The quantiles of medication adherence (40th quantile vs. 95th quantile) can be an indicator of a complex combination of inter- and intrapersonal factors. For instance, this study demonstrated that, at the 95th quantile, out-of-pocket costs for AET medication had a minimal influence on adherence. One reason could be because the patients had a comprehensive understanding of the importance of taking the medication despite the costs.23 Differences in adherence by AET drug type were not observed, even though exemestane and anastrozole were approved for generic use during the study period. We expect that the out-of-pocket costs for the drugs captured differences in adherence because of the change from brand name to generic.9 A significant association between switching AET medications was found that may have accounted for the side effects of treatment. The year of AET initiation was included in the quantile regression model to account for secular trends and patterns of medication fills, such as the change from brandname drugs to generic drugs and the downturn of the economy that occurred during the study period.

Similar to other studies, we found that using mail order pharmacies to fill prescriptions was associated with greater adherence compared with using retail pharmacies.7,8 Mail order pharmacies may increase adherence to AET because they eliminate the need for travel for patients with time and transportation constraints. Patients using mail order pharmacies may also be more inclined to purchase more medications than patients using retail pharmacies.24 However, unmeasured self-selection factors, such as race/ethnicity, could also account for the observed association, since non-Latino whites are more likely to use mail order pharmacies.25 Unlike other studies, however, the impact on adherence for women who used mail order pharmacies versus retail pharmacies was greatest in the 40th quantile of adherence, compared with the 95th quantile. This finding suggests that mail order pharmacies may substantially limit barriers to accessing medication among low adherers. Future studies should examine adherence particularly among retail pharmacies, since adherence was low among this group compared with patients who used any mail order pharmacy.

We found that women treated with chemotherapy were more likely to be adherent to AET compared with women not treated with chemotherapy across all quantiles of adherence. The effects were greatest in the 40th quantile compared with the 95th quantile. It is possible that women not treated with chemotherapy were misclassified into the study cohort because they filled 1 prescription of AET when they were not ER+. A study by Wang and Du (2015) found that 82% of women with ER+ breast cancer, treated with chemotherapy, initiated AET treatment versus 68% for women not treated with chemotherapy.26 They also found that women treated with chemotherapy who were diagnosed at a later stage were more likely to initiate AET, compared with women who were diagnosed at an earlier stage, and may have been more likely to continue AET to minimize the chance of recurrence.26 Finally, women who received chemotherapy may be less likely to discontinue AET medication because they may have a higher tolerance for side effects.27,28 We also observed that switching AET medication was associated with lower adherence at the 95th quantile; however, women who filled fewer prescriptions had fewer opportunities to switch medication.

This study has several strengths. A large cohort was used of privately insured women with a prescription drug coverage plan who were continuously insured for at least 18 months. Women in the cohort were recently diagnosed and treated with breast cancer; therefore, we were able to study adherence to AET during the first year of treatment, which may be the most critical period to address suboptimal adherence.4 Detailed baseline characteristics were also included, such as pill burden, time from treatment to initiation of AET, and the presence of comorbid conditions, which may have confounded the observed associations with adherence.

Limitations

Our study also has some limitations that need to be considered. First, calculating adherence using prescription claims assumes that patients are taking medications as often as they fill prescriptions; however, using pharmacy records is the most accurate and validated estimate of actual medication use in large populations over periods of time.29,30 Second, while claims and encounter data are reliable sources from which to determine prescription drug usage and medical procedures, clinical factors, such as stage of disease, are based on procedural and diagnostic algorithms, which may have misclassified patients that did not have observable codes.

Third, this study was not able to control for sociodemographic characteristics, such as race/ethnicity, education, or income, since these factors may be important confounders in our findings. A study by Hershman et al. (2010) did not find a significant association between these factors and adherence (MPR ≥ 80%) to AET in a group of commercially insured patients; however, the sociodemographic characteristics might be associated with AET discontinuation.6 Furthermore, all women in this study had employer-sponsored health insurance and may not be representative of women with low socioeconomic status.

Fourth, while we used data from the MarketScan databases, which contain data on more than 180 million commercially insured Americans, the women in our cohort were more likely healthier and younger than the general population, which may limit the generalizability of these findings beyond this population of women with breast cancer. Finally, women who died during the study period would not have been included in the analysis, since we only included women with 12 months of continuous enrollment in the MarketScan databases.

Implications for Future Research

The results of this study add to the literature on adherence to AET medications for women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. The quantiles of the distribution of adherence are a better measure than the mean because, in modeling the mean of skewered distributions such as adherence, the behavior of the mean often represents what is happening in the tails of the distribution.21 Even among a privately insured population, a suboptimal proportion of patients had less than 146 days of AET medication coverage in a 12-month period. Quantile regression allows us to draw conclusions about how each of the factors influence adherence at lower quantiles of adherence.

Our study has implications for future research. The use of mail order pharmacies and impact of out-of-pocket costs should be explored with patients that are low adherers of AET medication. This information could provide greater insight into important aspects of nonadherence among groups of patients that are least likely to continue medication. Also, randomized controlled trials should be used to establish the efficacy and safety of mail order pharmacies on adherence to AET medication.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence that factors such as the use of mail order pharmacies and 30-day out-of-pocket costs for AET medication influence adherence differently across levels of adherence even among a group of privately insured patients. Health insurance plans that allow patients the option to fill AET medication using mail order pharmacies may improve adherence, particularly among low adherers. The Affordable Care Act allows patients to access free preventive care and certain medications. Including AET medications at no out-of-pocket costs to patients may help improve adherence to AET.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Breast cancer facts & figures 2013-2014. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2013. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/document/acspc-042725.pdf. Accessed June 13, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Breast cancer. 2014. Version 2.2015. Available at: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp. Accessed June 13, 2016.

- 3.Davies C, Godwin J, Gray R, et al. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patientlevel meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):771-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Partridge AH, LaFountain A, Mayer E, Taylor BS, Winer E, Asnis-Alibozek A.. Adherence to initial adjuvant anastrozole therapy among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(4):556-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banning M. Adherence to adjuvant therapy in post-menopausal breast cancer patients: a review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2012;21(1):10-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hershman DL, Kushi LH, Shao T, et al. Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8,769 early-stage breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(27):4120-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neugut AI, Subar M, Wilde ET, et al. Association between prescription co-payment amount and compliance with adjuvant hormonal therapy in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(18):2534-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sedjo RL, Devine S.. Predictors of non-adherence to aromatase inhibitors among commercially insured women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;125(1):191-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hershman DL, Tsui J, Meyer J, et al. The change from brand-name to generic aromatase inhibitors and hormone therapy adherence for early-stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(11):dju319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gebregziabher M, Lynch CP, Mueller M, et al. Using quantile regression to investigate racial disparities in medication non-adherence. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoon J, Ettner SL.. Cost-sharing and adherence to antihypertensives for low and high adherers. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(11):833-40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juarez DT, Tan C, Davis JW, Mau MM.. Using quantile regression to assess disparities in medication adherence. Am J Health Behav. 2014;38(1):53-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimmick G, Anderson R, Camacho F, Bhosle M, Hwang W, Balkrishnan R.. Adjuvant hormonal therapy use among insured, low-income women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(21):3445-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandelblatt JS, Kerner JF, Hadley J, et al. Variations in breast carcinoma treatment in older medicare beneficiaries: is it black or white. Cancer. 2002;95(7):1401-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gross CP, Smith BD, Wolf E, Andersen M.. Racial disparities in cancer therapy: did the gap narrow between 1992 and 2002? Cancer. 2008;112(4):900-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srokowski TP, Fang S, Duan Z, et al. Completion of adjuvant radiation therapy among women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;113(1):22-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choudhry NK, Shrank WH, Levin RL, et al. Measuring concurrent adherence to multiple related medications. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(7):457-64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin BC, Wiley-Exley EK, Richards S, Domino ME, Carey TS, Sleath BL.. Contrasting measures of adherence with simple drug use, medication switching, and therapeutic duplication. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(1):36-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leslie RS. Using arrays to calculate medication utilization. Paper presented at: SAS Global Forum 2007; April 16-19, 2007; Orlando, FL. Available at: http://www2.sas.com/proceedings/forum2007/043-2007.pdf. Accessed June 13, 2016.

- 20.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM.. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koenker RW. Quantile Regression. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Efron B, Tibshirani R.. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. London: Chapman & Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fink AK, Gurwitz J, Rakowski W, Guadagnoli E, Silliman RA.. Patient beliefs and tamoxifen discontinuance in older women with estrogen receptor—positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(16):3309-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valluri S, Seoane-Vazquez E, Rodriguez-Monguio R, Szeinbach SL.. Drug utilization and cost in a Medicaid population: a simulation study of community vs. mail order pharmacy. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duru OK, Schmittdiel JA, Dyer WT, et al. Mail-order pharmacy use and adherence to diabetes-related medications. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(1):33-40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X, Du XL.. Socio-demographic and geographic variations in the utilization of hormone therapy in older women with breast cancer after Medicare Part-D coverage. Med Oncol. 2015;32(5):599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Demissie S, Silliman RA, Lash TL.. Adjuvant tamoxifen: predictors of use, side effects, and discontinuation in older women. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(2):322-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lash TL, Fox MP, Westrup JL, Fink AK, Silliman RA.. Adherence to tamoxifen over the five-year course. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;99(2):215-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choo PW, Rand CS, Inui TS, et al. Validation of patient reports, automated pharmacy records, and pill counts with electronic monitoring of adherence to antihypertensive therapy. Med Care. 1999;37(9):846-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steiner JF, Koepsell TD, Fihn SD, Inui TS.. A general method of compliance assessment using centralized pharmacy records. Description and validation. Med Care. 1988;26(8):814-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]