Abstract

Professional psychologists are increasingly encouraged to document and evaluate the quality of the treatment they provide. However, there is a significant gap in knowledge about the extent to which extant definitions of treatment quality converge with patient perceptions. The primary goal of this study was to examine how adolescent substance users (ASU) and their caregivers perceive treatment quality. The secondary goal was to determine how these perceptions align with expert-derived definitions of ASU treatment quality and dimensions of perceived quality used frequently in other service disciplines. Focus groups and individual interviews were conducted with 24 ASU and 29 caregivers to explore how participants conceptualize a quality treatment experience. Content analysis identified three major dimensions of perceived treatment quality, each of which contained three sub-dimensions: Therapeutic Relationship (i.e., Acceptance, Caring, Connection), Provider Characteristics (i.e., Experience, Communication Skills, Accessibility), and Treatment Approach (i.e., Integrated Care, Use of Structure, and Parent Involvement). Results revealed modest convergence between patient perceptions and existing definitions of quality, with several meaningful discrepancies. Most notably, the Therapeutic Relationship was the most important dimension to ASU and their caregivers, while expert-derived definitions emphasized the Treatment Approach. Implications for practicing psychologists to enhance training and supervision, quality improvement, and health education initiatives are discussed.

Keywords: adolescent, substance use, treatment, perceived quality

Improving the quality of treatment received by adolescent substance users (ASU) is a major priority for practicing psychologists in the United States. Nationally-representative surveys of the ASU treatment system (e.g., McLellan & Meyers, 2004; Ryan, Murphy, & Krom, 2012) have found that agencies serving ASU are rife with organizational, administrative and personnel barriers to implementing high quality treatment. Even when experts designate ASU programs as “exemplary” (e.g., Brannigan, Schackman, Falco, & Millman, 2004), a minority of programs use standardized substance use or mental health screening tools, collect data related to treatment outcomes, or design their curriculum to meet the needs of cultural minorities.

In the quest to enhance treatment quality, experts have identified requisite features of effective ASU treatment programs (see National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2014). Most recently, building upon work by Drug Strategies (Brannigan et al., 2004), Meyers and colleagues (2014) developed a list of 10 key characteristics (KCs) of quality ASU treatment that have strong empirical, clinical, and expert support as contributing to reductions in substance related problems among adolescents. Each KC is an objective treatment feature such as whether the agency used a standardized assessment tool, provided integrated care, or involved the family. Practicing psychologists and agencies are increasingly encouraged to use these types of expert-derived rubrics to document and evaluate the quality of the treatment they provide (Drogin et al., 2010; Nix, 2013; Zima et al., 2013).

There is a significant gap in knowledge about the extent to which expert-derived metrics such as these converge with patient perceptions of quality. Understanding how patients perceive treatment quality is vitally important for at least four reasons. First, examining how patients define and evaluate quality is consistent with the move toward a more patient-oriented health care system (see Institute of Medicine, 2001). Second, patients’ perceptions of quality are critical determinants of individual health-seeking behaviors, treatment utilization, compliance, and complaints (see Sofaer & Firminger, 2005). Third, there is evidence from other fields and areas of healthcare that how patients perceive treatment quality is a more important determinant of patient satisfaction than the technical quality of treatment (e.g., accuracy of diagnoses or procedures; Grönroos, 1984, Mosadeghrad, 2012). Finally, identifying aspects of treatment quality most valued by patients can inform direct-to-consumer marketing and health education initiatives, which can promote increased utilization of effective treatments (Becker, 2015a, b).

Extensive research on the perceived quality construct has been conducted in the field of services marketing, an academic discipline focused on the marketing of professional services such as telecommunications, finance, hospitality, and healthcare (see Zeithaml, Bitner, & Gremler, 2012). Through the pioneering work of market researchers Parasuraman, Berry, and Zeithaml (1983; 1991a; 1991b; 1993) five dimensions of perceived quality have been identified as applicable across a variety of service contexts including healthcare: Reliability, Assurance, Responsiveness, Empathy, Tangibles. Each dimension focuses on how the person receiving the service perceives the quality of the experience. These five dimensions form the basis of the SERVQUAL, a questionnaire that is widely considered to be the gold standard measure of perceived quality (see Gagić, Tešanović, & Jovičić, 2013; Murrow & Murrow, 2002). To date, the SERVQUAL has been used, translated, and adapted in over 120 service industries and 40 countries (see Ladhari, 2009), including multiple studies of healthcare service quality (see Chakraborty & Majumdar, 2011 for a review). By contrast, only one study of patients with mental health problems (Tempier et al., 2010) and no study of patients with substance use problems have measured perceived treatment quality.

This qualitative study is the first to examine perceptions of treatment quality among ASU treatment recipients. Since caregivers (e.g., parents and legal guardians) play a vital role in decisions about adolescent treatment utilization (Nock & Ferriter, 2005), we included both caregivers and ASU in the study. Our primary goal was to examine the dimensions of perceived treatment quality most valued by ASU and caregivers. Our secondary goal was to explore the degree to which these dimensions overlapped with well-established quality metrics: namely, the 10 expert-derived characteristics of quality ASU treatment and the five dimensions of perceived quality used widely in other service disciplines.

Methods

Recruitment

This study was part of a research program focused on increasing ASU treatment utilization (see Becker, Spirito, & Vanmali, 2015). ASU and caregivers were recruited in the northeast region of the United States between November 2012 and August 2014. Purposive sampling was used to recruit participants from clinics encompassing the full ASU continuum of care: one primary care clinic, one outpatient mental health clinic, one emergency department, one outpatient substance use program, and one residential substance use program. Each clinic posted advertisements about the study. Treatment providers in each clinic also invited potentially eligible caregivers to sign Consent to Contact forms indicating their willingness to be contacted by study staff.

Caregivers needed to meet three inclusion criteria: a) legal guardian of a teen aged 12 to 17, b) fluent in English, and c) report that their teen had risky levels of substance use on a brief screening measure (Global Appraisal of Individual Needs – Short Screener; Dennis, Chan, & Funk, 2006). Adolescents automatically qualified for inclusion if their caregivers met these criteria. Because research consistently indicates that caregivers are more likely than teens to make decisions related to treatment selection and utilization (Nock & Ferriter, 2005), we based eligibility on the caregiver’s impression of the teen’s substance use rather than an objective assessment or diagnostic interview with the adolescent. We continued recruiting until we obtained saturation, which we defined as the point at which new data collection did not provide additional information on the two primary research questions (Sandelowski, 1995).

Data Collection

Data collection procedures were determined in collaboration with agencies where we recruited and approved by an academic medical center’s institutional review board. The original plan was to invite all ASU and caregivers to participate in separate, face-to-face interviews lasting 45–60 minutes. However, residential program staff requested that ASU and caregivers be given the choice of participating in individual interviews or focus group discussions in order to minimize participant burden and fit within the constraints of the residential center’s schedule. We therefore offered separate focus groups for ASU and parents recruited from the residential center, ranging from 4–6 participants per group and lasting 75–90 minutes.

Prior to the start of each focus group or interview, caregivers provided written consent, while adolescents provided written assent. Caregivers and adolescents also completed a few brief measures. Caregivers completed a brief questionnaire about the adolescents’ demographics and treatment history, while adolescents completed scales from a well-validated family of substance use assessment tools (Global Appraisal of Individual Needs or GAIN; Dennis, White, Titus, & Unsicker, 2008). These supplemental measures provided a cursory indication of the adolescent’s history of treatment utilization, current level of substance use severity, and symptoms of co-occurring mental health problems.

Semi-structured protocols were used to guide the focus groups and individual interviews. At the start of each discussion, ASU and caregivers were explicitly asked whether their perceptions of quality depended more on the characteristics of the individual provider (i.e., therapist, counselor, or psychologist) or the treatment program, in order to determine the optimal frame for subsequent questions. In the case of discrepant answers within focus groups, participants were asked to clarify their preferred focus (i.e., individual provider or treatment program) before answering questions. The remainder of the discussion consisted of open-ended questions about how participants define and evaluate treatment quality. The questions focused on treatment factors that influence perceptions of quality on an ongoing basis, and did not explore factors that influence the feasibility of receiving the treatment such as price or convenience. Questions were asked broadly in order to spontaneously elicit as many dimensions of perceived treatment quality as possible.

A licensed clinical psychologist with 10 years of qualitative research experience led the focus groups and individual interviews. A trained Research Assistant (RA) attended each discussion and took process notes. Discussions were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Qualitative Thematic Analysis

Using principles of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), the analysis began with identification of emergent themes. The goal of the analysis was to identify the full range of quality dimensions that emerged from the data; hence, the analysis focused on understanding diversity in the dimensions and not on quantifying their frequency (Hannah & Lautsch, 2010). Three independent coders first read the transcripts in their entirety to get a sense of the whole dataset. Following this reading, 10% of the transcripts were randomly reviewed and preliminary codes were assigned to the data. The coders met to discuss the preliminary lists, identify any discrepancies in meaning assigned to each code, and finalize a set of common codes. The coders started by agreeing on broader, higher-order dimensions of quality that were present in the dataset, and then these broad dimensions were divided into sub-dimensions. Remaining transcripts were analyzed independently by the coders, who met weekly. If marked text did not fit an existing category, new codes were proposed during the weekly meetings. Codes that were unanimously agreed upon were added and prior transcripts were re-analyzed as necessary. In cases of discrepancies, the coders re-examined the transcripts together and discussed possible thematic meanings associated with the text in question until they reached agreement. Throughout the process, the coders attended to potential thematic variation by the adolescent’s level of care and sex, as these variables have been associated with ASU symptom presentation and treatment-seeking behaviors (Brady & Randall, 1999; Herron & Brennan, 2015).

To address the second objective, concept mapping (Burke et al., 2005) was applied to map the emergent themes onto the 10 expert-derived KCs and five SERVQUAL dimensions. Code books containing detailed definitions of the KCs and SERVQUAL dimensions were used to facilitate independent mapping by each coder (see Table 1 for an overview). The maps were then reviewed jointly by the coders, who discussed the assignments until reaching 100% consensus. NVivo software (QSR International, 2012) was used to record the development, definition, and organization of codes.

Table 1.

Definitions of Expert-Derived Key Characteristics and SERVQUAL Dimensions Used in Concept Mapping

| Concept | Definition |

|---|---|

| Expert-Derived Key Characteristics (10) | |

| Assessment | Program uses a standardized assessment tool for diagnosis and treatment planning |

| Attention to mental health | Program assesses adolescent’s mental health and addresses concerns proactively |

| Comprehensive, integrated treatment | Program assesses and proactively addresses factors related to the adolescent’s substance use such as physical health, education/vocational status, victimization, legal involvement, and sexual health. |

| Family involvement | Program directly involves family in the treatment and recovery process. |

| Developmentally informed programming | Program utilizes developmentally-appropriate approaches to treatment. |

| Engage and retain adolescents | Program implements strategies for actively engaging adolescents in the treatment process. |

| Staff qualifications and training | Program staff are experienced and receive ongoing training to ensure the delivery of highest quality treatment. |

| Person-first treatment | Program delivers treatment that is personalized and sensitive to issues pertaining to cultural background, gender, sexual orientation, and other identity markers. |

| Continuing care and recovering supports | Program provides accessible, ongoing services to sustain long-term recovery. |

| Program evaluation | Program has comprehensive protocols for evaluating the quality of treatment. |

|

| |

| SERVQUAL Dimensions (5) | |

| Tangibles | Service provider has physical facilities, equipment, personnel, and communication materials that appeal to the consumer. |

| Reliability | Service provider is able to perform the required service dependably. |

| Responsiveness | Service provider demonstrates willingness to help and provide prompt service. |

| Assurance | Service provider exhibits knowledge and conveys trust and confidence. |

| Empathy | Service provider displays caring, individualized attention to the consumer. |

Note: Expert-derived key characteristics are based on those listed in Appendix A of the report Paving the Way to Change by Meyers et al., 2014. SERVQUAL dimensions are the five dimensions comprising the well-validated measure of service quality developed by Parasuraman et al., 1998.

Findings

Sample Characteristics

The final sample consisted of 29 caregivers (18 caregivers of males, 11 of females) and 24 ASU (17 males, 7 females). Across the full sample of 53 participants, the majority (n = 36) were Caucasian, with representation of Hispanic/Latino (n = 9), African-American (n = 6), and other racial/ethnic groups (n = 2). Of the 29 caregivers, 26 were mothers, two were fathers, and one was a grandmother. Fifteen caregivers were single parents with sole custody. Median household income was $29,750 with a large range from $13,000 to over $200,000. The caregivers reported high rates of current ASU treatment utilization: 12 teens were in residential treatment, 13 were in outpatient treatment, and four teens were not currently in treatment.

Among the 24 adolescents, self-reported rates of substance use and co-occurring mental health problems were high. Based on responses to the GAIN, 16 of the teens met past-year DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) criteria for substance dependence, 4 met for substance abuse, and the remainder had risky levels of use. In addition, 10 adolescents had symptoms suggestive of an “internalizing” mental health issue (i.e., depression, anxiety, acute stress) and 16 had symptoms suggestive of an “externalizing” mental health problem (i.e., disruptive behavior disorder, attentional disorder).

Emergent Themes: Dimensions of Perceived Treatment Quality

ASU and caregivers unanimously asserted that they cared more about the characteristics of their specific treatment provider than the characteristics of a program. Hence, emergent themes were defined based on the degree to which they represented responses to a specific treatment provider (i.e., therapist, counselor, or psychologist).

Thematic analysis identified three broad dimensions of perceived treatment quality: Therapeutic Relationship, Provider Characteristics, and Treatment Approach. Each of these three dimensions encompassed three sub-dimensions. We present definitions and illustrative quotes for each of the nine sub-dimensions in Table 2 and elaborate below. For simplicity, the teen’s age is denoted by a number and the teen’s sex is indicated by M for male and F for female.

Table 2.

Definitions of Dimensions and Sub-Dimensions Identified via Thematic Analysis with Illustrative Quotes

| Dimensions | Definition | Parent Quote(s) | Adolescent Quote(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Relationship | |||

| Acceptance | Subjective sense that the provider does not judge, but rather validates the adolescent’s and caregiver’s experience |

|

|

| Caring | Perception that the provider is genuinely invested in the well-being of the adolescent and family |

|

|

| Connection | Feeling connected with the provider, which makes the adolescent feel comfortable engaging in sessions |

|

|

|

| |||

| Provider Characteristics | |||

| Experience | Perception that the provider projects confidence due to relevant experience with adolescents |

|

|

| Communication Skills | Provider’s perceived ability to listen and explain things well |

|

|

| Accessibility | Perception that provider can be reached both for an initial session and during emergent clinical issues |

|

|

|

| |||

| Treatment Approach | |||

| Integrated Care | Perception that treatment addresses co-occurring mental and physical health issues |

|

Not discussed by the adolescents |

| Use of Structure | Perceived use of structure within each treatment session (i.e., goal/agenda setting, learning skills, and out of session practice) |

|

|

| Parent Involvement | Sense that provider is able to respectfully involve parents and address confidentiality. |

|

|

Dimension 1: Therapeutic Relationship

The first dimension of perceived treatment quality was the Therapeutic Relationship, which referred to the extent to which the provider was able to form a meaningful, productive relationship with the teen. Many caregivers and ASU explicitly described this dimension as the most important element of a quality treatment experience, using terms such as “critical,” “essential,” and “the foundation.” The three sub-dimensions of the Therapeutic Relationship were Acceptance, Caring, and Connection. These three sub-dimensions were mentioned by both ASU and caregivers, and did not appear to vary by the teen’s sex or level of care.

Acceptance

The first sub-dimension was the provider’s ability to convey Acceptance. Both caregivers and ASU defined Acceptance as entailing both the absence of judgment and the presence of validation. For ASU, an “unbiased” provider was someone who did not judge or criticize their behavior. For caregivers, a “non-judgmental” provider was someone who listened to their struggles without questioning or “blaming” their parenting. Multiple caregivers shared stories of how a lack of Acceptance had negatively influenced their teen’s engagement in treatment. As an example, a mother of a 17F reported that her daughter had “broken up” with a counselor because “when she slipped [relapsed] again… the therapist started to speak derogatory towards her …. That got to her.”

Acceptance also consisted of a sense of validation, conveyed as a meaningful understanding and affirmation of the patient’s unique experience. Both ASU and caregivers expressed a desire to feel “understood” and “accepted.” A 16M described his ideal provider as someone who would “be understanding and acknowledge how difficult the situation is… and not just say ‘This is the problem, this is what we are going to do to fix it.’” Numerous participants also explicitly stated that acceptance required consideration of their culture, race/ethnicity, family background, and/or personal history.

Caring

The next sub-dimension was Caring, characterized as a sense that the provider was genuinely invested in the well-being of the teen and the teen’s family. Caregivers captured this sub-dimension using phrases including, “invested,” “warm,” “compassionate,” “interested in getting to know my child,” “there for your needs,” and “personal interest.” Meanwhile, teens used descriptive terms such as, “actually care,” “really want to help you,” “try and help you,” and “really into their job.” For many caregivers and ASU, a primary indicator of a caring therapist was a subjective feeling of “being liked.”

Another central sign of a caring therapist was a sense that the provider was going “above and beyond” what was required. Both caregivers and ASU noted that a truly caring provider did not just help because it was “their job” or “for the money,” but because they “have good intentions at heart” and are “interested in forming a relationship.”

Connection

The final aspect of the Therapeutic Relationship mentioned by ASU and caregivers was a sense of Connection, described using words such as “connect,” “bond,” “hit it off,” “chemistry,” and “click.” One indicator that the provider had formed a quality connection was a subjective feeling of comfort, which several ASU and caregivers described as a requisite for effective treatment. As illustration, a mother of a 17M remarked, “to form that bond and see results you need to be comfortable” while a 17F said, “you can’t get better if you don’t feel comfortable with your therapist.”

Another indicator of Connection was the adolescent’s level of engagement, indicated both by the adolescent’s attendance and level of participation in sessions. Several caregivers asserted that teens needed to feel connected or else they would refuse to attend sessions. Meanwhile, both caregivers and ASU acknowledged that a provider’s ability to connect with teens had a positive effect beyond basic attendance, by influencing the teens’ willingness to cooperate and “open up” during sessions.

Dimension 2: Provider Characteristics

The second major dimension of perceived treatment quality was Provider Characteristics, which reflected whether a provider was perceived as having three requisite traits: Experience, Communication Skills, and Accessibility. Unless otherwise specified, the sub-dimensions were discussed by both ASU and caregivers and did not appear to vary by sex or level of care.

Experience

The first Provider Characteristic was perceived Experience, which encompassed both the provider’s past work with ASU and ability to project confidence. Both caregivers and ASU consistently stated that they wanted a provider with experience working with adolescents with similar issues. Multiple caregivers and teens commented that relevant experience was more important than professional credentials such as degrees, licenses, or certifications.

Additionally, both ASU and caregivers stated that it was important for providers to project confidence in their ability to help. Numerous caregivers described confidence as a key indicator of Experience, noting that confidence “reflects competence” and is “reassuring.” Both male and female ASU also designated confidence as essential, with several teens saying they wanted a provider who “is confident,” “tells you straight up,” and isn’t “on edge about what he is going to say.” Of note, one 15M was quick to note that he wouldn’t like a provider who made lofty promises about his/her ability to help as that would seem “a little too overconfident.”

Communication Skills

Another Provider Characteristic was Communication Skills, defined as the provider’s ability to both explain things clearly and listen actively. The first aspect was the provider’s ability to help caregivers and ASU understand the information being conveyed. Several caregivers voiced a desire for a provider who could talk with teens at the “right level” and with “the lingo” in a way they themselves could not. ASU similarly stated that they wanted their provider to “talk on my level,” “work with me,” and “explain things” clearly. The ASU also explicitly noted communication tendencies that they did not appreciate from a provider, such as “lecturing more than talking,” “telling me to do this or do that,” talking too much (i.e., “talking blah blah blah”), asking “the same question over and over,” making comments that are unclear or “confusing,” and giving advice that sounds “generic.”

The second component of Communication Skills was the provider’s ability to listen well. Per the caregivers and ASU, a provider with good listening skills demonstrated multiple observable behaviors in sessions, of which “good eye contact” was the one described as most important. Other observable indicators of listening mentioned by both caregivers and teens included: a) offering effective summary statements (e.g., “every time I said something he’d repeat it and say, ‘So what I’m hearing you say is…”), b) providing relevant feedback (e.g., “if they listened to you and gave you feedback”), c) noting patterns in comments or behaviors (e.g, “they will be able to pick up on verbal cues, visual cues”), and d) remembering details from session to session (e.g., “pay enough attention to the fine detail”). The caregivers and teens both commented that when providers demonstrated these behaviors, it led to subjective feelings of being “heard,” “understood,” or “cared about.”

Accessibility

The final component of Therapeutic Competence was the provider’s Accessibility, which reflected the ease of both getting in for a session and reaching the provider during emergent clinical issues. Caregivers, in particular, reported that Accessibility when scheduling an initial appointment was a critical determinant in their selection of a provider. Comments about the Accessibility of initial appointments were by only one 16M, who communicated frustration with his family’s difficulty finding an available provider at the time when he most needed help.

The provider’s Accessibility outside of session, defined as a willingness to respond to emergent clinical issues, was also deemed vital by caregivers and ASU. Of note, several caregivers commented that the primary provider didn’t have to be reachable outside of session, as long as the provider’s team or clinic could be contacted. ASU and caregivers across all levels of care conveyed a desire to schedule appointments quickly, while ASU and caregivers already in treatment seemed especially interested in having someone reachable in between sessions.

Dimension 3: Treatment Approach

The final dimension of perceived treatment quality was labelled the Treatment Approach and included the provider’s specific methods and treatment elements. Caregivers and ASU described three specific sub-dimensions of the Therapeutic Approach: Integrated Care; Use of Structure; and Parent Involvement. Overall, comments about the Treatment Approach sub-dimensions did not appear to vary substantially by the adolescent’s sex or level of care.

Integrated Care

A sub-dimension mentioned by multiple caregivers but none of the ASU was the extent to which treatment addressed co-occurring mental and physical health issues. One mother of a 16M noted that it was crucial for the provider to recognize that “kids have other issues, they are not just substance users.” In particular, several caregivers referred to substance use and mental health as inseparable issues that needed to be treated in kind.

A number of caregivers asserted that lack of coordination among providers had significantly reduced the effectiveness of their teen’s treatment. For instance, one mother of a 15M shared a story about how lack of coordination among three providers (i.e., a therapist, psychiatrist, and behavioral specialist) delayed her son’s diagnosis by over a year. Conversely, a mother of a 17F asserted that collaboration between a therapist and a psychiatrist had enhanced her daughter’s treatment, by addressing her daughter’s tendency to use substances to self-medicate her anxiety.

Use of Structure

Both caregivers and teens described Use of Structure as another aspect of the Treatment Approach that influenced treatment quality. This sub-dimension pertained primarily to structural elements within each session and not to the overall structure of the treatment program. In particular, caregivers and ASU voiced interest in goal and/or agenda setting, learning coping skills, and practicing coping skills outside of sessions.

Regarding goal and/or agenda setting, several caregivers said they wanted their provider to set treatment goals upfront and track progress towards the goals in subsequent sessions. As an illustration, a father of a 15F wanted a provider to help his daughter to set goals and track progress towards meeting them. Meanwhile, ASU comments expressed a desire for structured session agendas instead of “unstructured chatter.”

Concerning coping skills, both caregivers and ASU indicated a desire for new “tools,” “strategies,” rechanneling,” or “retraining” to help the teen reduce his/her substance use. A few caregivers commented that learning skills was especially important for teenagers, since teenagers often “don’t slow down” and “just rush ahead.” Caregivers conveyed interest in coping skills such as “retraining the brain,” “calm[ing] the body,” and “occupying my son’s time with something good,” while ASU communicated interest in analogous skills such as learning “to think positive about things,” discovering “steps and strategies,” and “keeping myself busy.” Of importance, several ASU commented that the therapist needed to introduce skills in a “flexible,” adolescent-centric manner (i.e. to demonstrate Acceptance) or else the sessions could become uncomfortable and feel too “by the book,” “cookie cutter,” or “like school.”

Finally, in regard to practicing skills, both caregivers and ASU expressed a need for help applying new strategies outside of sessions. Caregivers and ASU in residential treatment were especially interested in finding a therapist who could help them to translate skills to “the out,” “the outside” or to “your real life.”

Parent Involvement

The final sub-dimension was Parent Involvement. Important aspects that emerged in the qualitative data included respect for the caregiver’s authority, parent attendance, and attention to confidentiality.

One issue that was emphasized by many caregivers but not mentioned by any ASU was the provider’s respect for the caregivers’ authority. Several caregivers expressed dissatisfaction with providers who they perceived as advocating parenting practices at odds with their “rules,” “views,” or “values.” Meanwhile, other caregivers recalled instances when providers appeared to discount the parent’s perspective or tell them that they were “not right” about their teen. One father of a 15M stated that if a provider did not respect his wishes as a parent it would be a “deal breaker” that would lead him to terminate his son’s treatment.

A second preference mentioned by multiple caregivers and a few ASU was having parents attend sessions. Perceived benefits of parent attendance included: a) helping “the family get well”; b) making the teen “feel that support from the family”; c) role modeling (“the kids see”); d) improved relationships (“we get along better”); e) improved communication (“we could talk about it”); f) “educating” the caregivers; g) giving the caregivers “tools”; and h) reducing caregiver stress (“it kept me sane”). Two caregivers (father of a 15M and mother of a 17F) found being included in their teenager’s sessions so helpful that they labelled parental attendance a “bare minimum” and “mandatory” requirement, respectively. Remarks about parent attendance were made less often by ASU and those who commented had mixed support for the idea. Three teens described parent attendance as “uncomfortable,” putting the teen “in the middle” and turning “little things to big things,” while another three teens referred to parent attendance as “fixing family issues,” “a help to my parents” and making the teen “able to talk more about things.”

A final aspect of Parent Involvement was the management of confidentiality concerns. For the caregivers this meant that the provider would respect the teen’s privacy, while making sure that the caregiver had enough information to “keep my child safe.” Caregivers of both males and females expressed disappointment with prior therapists who had gone “too far” in protecting the teen’s confidentiality about serious drug use or high-risk behavior. Meanwhile, for ASU, it was imperative that the provider would protect their privacy and clarify limits of confidentiality.

Concept Mapping: Comparing Dimensions to Existing Metrics

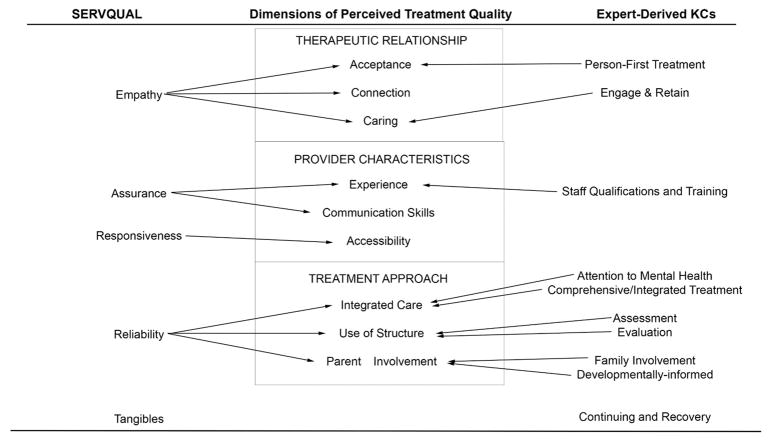

Figure 1 depicts how the dimensions of perceived treatment quality mapped onto the 10 expert-derived KCs and five SERVQUAL domains. With regard to the expert-derived KCs, nine of the 10 were covered by the perceived quality dimensions. The only KC that was not covered was Continuing and Recovery. Of note, six of the ten KCs mapped onto the Treatment Approach dimension. In general, the definitions of the KCs were consistent with the definitions of the quality dimensions; the only disconnect was between the “Staff Qualifications and Training” KC and the Experience sub-dimension. The KC definition prioritizes objective credentials, while ASU and caregivers explicitly stated that they valued relevant experience more than prior degrees, certifications, and licenses.

Figure 1.

Comparison of Dimensions of Perceived Treatment Quality with Expert-Derived Key Characteristics (KCs) of Quality and SERVQUAL dimensions. Expert-derived KCs are taken from the Treatment Institute’s report Paving the Way to Change (Meyers et al., 2014). SERVQUAL is a well-validated measure of service quality used extensively in other service disciplines (Parasuraman, Berry, & Zeithaml, 1988).

Regarding the SERVQUAL domains, four of the five were covered by the quality dimensions. The only SERVQUAL domain that was not covered was Tangibles. In general, the SERVQUAL definitions were well-aligned with the definitions of the perceived quality dimensions.

Discussion

Our study identified three major dimensions of perceived treatment quality: Therapeutic Relationship, Provider Characteristics, and Treatment Approach. Therapeutic Relationship captured the desire of caregivers and ASU to form a comfortable connection with an accepting and caring provider. Provider Characteristics reflected the importance of the provider’s experience, communication skills, and accessibility. Finally, Treatment Approach revealed a preference for treatment that is integrated, structured, and involves parents. Although each of these dimensions represented a unique aspect of perceived treatment quality, they were interrelated and often bi-directional. For instance, some caregivers and ASU noted that their relationship with the provider positively influenced their impressions of the provider and the approach, while others noted that their impressions of the provider and the approach directly affected their ability to form a positive relationship.

The three higher-order dimensions were consistent across level of care and sex of the ASU, with the exception of minor points of emphasis (e.g., ASU in treatment cared most about Accessibility between sessions whereas ASU not in treatment cared most about Accessibility of the first session). The dimensions also demonstrated high levels of coverage of the expert-derived KCs of quality treatment and the five SERVQUAL dimensions, suggesting that what matters most to ASU treatment recipients is similar to what concerns ASU experts and service recipients in other fields. However, there were several meaningful discrepancies between our findings and extant quality systems, which raise important considerations for practicing psychologists.

First and most notably, there were differences in perceived importance. Of the three perceived treatment quality dimensions, Therapeutic Relationship was the one described as most vital by many of the caregivers and ASU. By contrast, the Treatment Approach was the dimension that encompassed the most expert-derived KCs and corresponded with the SERVQUAL dimension that has been found to be “the most important determinant” by the questionnaire developers in empirical research (Zeithaml et al., 2012, p. 89). The importance of the Therapeutic Relationship to participants in this study was not surprising, however. There is a wealth of literature documenting the importance of the Therapeutic Relationship on patient outcomes such as treatment engagement, compliance, and satisfaction (Norcross, 2011). Indeed, decades of research have shown that the common factors related to the Therapeutic Relationship - such as empathy, warmth, and the interpersonal connection between therapist and patient – are often more correlated with treatment outcome than the specific approach (see Lambert & Barley, 2001). Within the marketing literature, healthcare studies using the SERVQUAL have similarly documented the relative importance of the Empathy dimension (Chakraborty, & Majumdar, 2011). Perhaps the most critical implication of our study (elaborated below) is that expert-derived definitions of quality and initiatives designed to improve quality should attend more to this dimension.

Second, the dimensions of perceived treatment quality covered all but one of the expert-derived KCs. The KC that was not mentioned by caregivers or ASU was “Continuing Care and Recovery Supports.” According to Meyers and colleagues (2014), this attribute is characterized by features such as provision of relapse prevention services, development of a continuation of care and recovery plan, linking the family to community resources, and monitoring the family via periodic check-ins. In qualitative research, the absence of a theme does not imply that it is not important, but rather might reflect the characteristics of the sample or scope of discussions (Braun & Clarke, 2006). In the current study, the omission of comments about recovery and continuing care might reflect our sample, which was primarily comprised of ASU in an active treatment episode as opposed to adolescents in recovery. It is possible that the ASU and caregivers in our sample may not yet have had a long-term addiction perspective characterized by multiple attempts to stop using substances and therefore may not have appreciated the value of continuing support. Future research is needed to explore this issue.

Third, the dimensions mapped onto four of the five SERVQUAL domains. Only one SERVQUAL domain was not covered by our results: Tangibles, which pertains to the attributes of the physical facilities, equipment, personnel, and communication materials. In contrast to the omitted KC “Continuing Care and Recovery Supports” discussed above (which simply wasn’t mentioned), the missing SERVQUAL domain Tangibles was spontaneously mentioned by multiple ASU and caregivers, but was subsequently described as relatively unimportant. For instance, the mother of a 15F specifically said, “It’s the person not the place,” and a 16M similarly claimed, “The place doesn’t matter as long as I’m getting the treatment I need.” Although not expected, this finding is consistent with the services marketing literature, which has found Tangibles to be the least influential and reliable dimension of perceived service quality (Parasuraman et al., 1991a; Parasuraman et al., 1988), especially in the healthcare field (Chakraborty, & Majumdar, 2011).

Limitations

Several limitations influence the interpretation of our results. A primary consideration pertains to the composition of our sample. Even though our sample was economically diverse, most participants were recruited from treatment or primary care clinics and were therefore engaged in the healthcare system to some degree. We also recruited in a northeast region of the United States where there was access to at least one outpatient ASU center and at least one residential ASU center. It is possible that families who were not currently engaged in the healthcare system or who lived in regions with less access to care might have had different perspectives on the features of quality treatment. Another issue was our mix of focus groups and interviews. Based on feedback from program staff, we allowed families involved in residential treatment to choose either a focus group or interview, while other families all received individual interviews. Even though we used identical guides, social facilitation in the focus groups might have influenced the diversity of viewpoints that were expressed in that setting.

Practice Implications

Results of this study have meaningful clinical and research implications for practicing psychologists who work with ASU (many of whom are likely to have co-occurring mental health issues). It is possible that these implications would also be relevant to psychologists working with other patient populations (e.g, different ages, presenting concerns, etc.), though additional research is needed to explore the generalizability of these dimensions.

One implication of our results is that a reliable, valid measure of patient perceived treatment quality could have significant value. The benefits of using SERVQUAL and its sound psychometric properties are well-documented in other service fields, where SERVQUAL is frequently used to assess perceptions of quality, identify quality shortcomings, and develop targeted quality improvement plans (Ladhari, 2009; Zeithaml et al., 2012). While our results suggested reasonable overlap with SERVQUAL, we found a number of unique sub-dimensions of treatment quality. Development and testing of a new perceived quality measure for ASU treatment is therefore warranted. Our team is currently testing a pool of preliminary items based on the qualitative feedback shared here to support development of such a measure. For the three perceived quality dimensions to be beneficial for practicing psychologists, it will be imperative to test whether they have predictive validity. In other words, it will be important to evaluate if the dimensions predict meaningful clinical outcomes – such as treatment initiation, engagement, compliance, and reduction of substance-related problems.

If the dimensions described here were found to have predictive validity, then our findings would have two other important practice implications. First, psychologists and agencies seeking to provide quality care would likely benefit from paying more attention to the Therapeutic Relationship in training, supervision, and quality improvement initiatives. Many training, quality improvement and program evaluation initiatives focus on objective elements of the Treatment Approach, consistent with expert-derived definitions of quality. Ensuring that training and supervision emphasize how psychologists can come across as caring, accepting, and able to form a meaningful connection could help to promote a more-centric approach to care. Similarly, integrating questions about the Therapeutic Relationship into program evaluation initiatives could help to ensure that the programs are evaluated using metrics that matter to patients. These recommendations are consistent with the conclusion of Lambert and Barley (2001) in their widely cited review on the influence of the therapeutic relationship on therapy outcome: “clinicians must remember that this [the therapeutic relationship] is the foundation of our efforts to help others.”

Second, our findings suggest that psychologists and agencies seeking to educate potential patients through health education or direct-to-consumer marketing initiatives might benefit from highlighting the value of the Treatment Approach. This dimension mapped onto the most expert-derived KCs, but was not the most important dimension to the ASU and caregivers in this study; this suggests significant opportunity to educate ASU and caregivers about the benefits of the Treatment Approach and the specific elements of treatment that they should seek out.

In summary, our results suggest that relying on existing quality systems such as those derived by experts or those used in other fields, may miss dimensions of quality that patients and caregivers value. In particular, our results suggest that expert-derived quality systems may not place sufficient emphasis on the therapeutic relationship, which was the dimension most valued by adolescents and their caregivers. By listening to patients and caregivers about what they want out of a quality treatment experience and adjusting treatment delivery accordingly, practicing psychologists may be able to improve patients’ perceptions of quality, satisfaction, and loyalty.

Biographies

SARA BECKER received her PhD in clinical psychology from Duke University. She is an Assistant Professor (Research) at the Center for Alcohol and Addictions Studies in the Brown School of Public Health. Her clinical research interests include direct-to-consumer marketing of behavioral treatment, addiction health services research, and training adolescent substance use treatment providers.

MIRIAM MIDOUN received her ScM in behavioral and social sciences from the Brown School of Public Health. She is the Project Coordinator of several NIH-funded grants at the Center for Alcohol and Addictions Studies in the Brown School of Public Health. Her areas of interest include qualitative research, sociocultural determinants of health inequality, and social justice.

VALARIE ZEITHAML received her PhD in marketing from the University of Maryland. She is the David Van Pelt Family Distinguished Professor of Marketing at the Kenan-Flagler Business School at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She is also the incoming Chairman of the Board at the American Marketing Association. Her areas of professional interest include perceived service quality, service quality management, and services marketing.

MELISSA CLARK received her PhD in community health sciences from the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health. She is a Professor in the Department of Quantitative Health Sciences and the Center for Health Policy and Research at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Her areas of research focus include mixed-methods (qualitative and quantitative) approaches, questionnaire design and validation, and survey methodology.

ANTHONY SPIRITO received his PhD in clinical psychology from Virginia Commonwealth University. He is a Professor and the Vice Chair of Psychiatry and Human Behavior at Alpert Medical School of Brown University. His areas of clinical research interest include adolescent substance use treatment, adolescent depression and suicide treatment, and parenting interventions.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- Becker SJ. Direct-to-consumer marketing: A complementary approach to traditional dissemination and implementation efforts for mental health and substance abuse interventions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2015a;22:85–100. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SJ. Evaluating whether direct-to-consumer marketing can increase demand for evidence-based practice among parents of adolescents with substance use disorders: Rationale and protocol. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2015b;10:4. doi: 10.1186/s13722-015-0028-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SJ, Spirito A, Vanmali R. Perceptions of “evidence-based practice” among the consumers of adolescent substance use treatment. Health Education Journal. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0017896915581061. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Randall CL. Gender differences in substance use disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1999;22(2):241–252. doi: 10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannigan R, Schackman BR, Falco M, Millman RB. The quality of highly regarded adolescent substance abuse treatment programs: results of an in-depth national survey. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158(9):904–909. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.9.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JG, O’Campo P, Peak GL, Gielen AC, McDonnell KA, Trochim WM. An introduction to concept mapping as a participatory public health research method. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(10):1392–1410. doi: 10.1177/1049732305278876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty R, Majumdar A. Measuring consumer satisfaction in health care sector: the applicability of SERVQUAL. International Journal of Arts, Science and Commerce. 2011;2(4):149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Chan YF, Funk RR. Development and validation of the GAIN Short Screener (GSS) for internalizing, externalizing and substance use disorders and crime/violence problems among adolescents and adults. American Journal of Addiction. 2006;15(Suppl 1):80–91. doi: 10.1080/10550490601006055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, White M, Titus JC, Unsicker J. Global Appraisal of Individual Needs: Administration Guide for the GAIN and Related Measures (Version 5) 2008 Retrieved http://www.gaincc.org/_data/files/Instruments%20and%20Reports/Instruments%20Manuals/GAIN-I%20manual_combined_0512.pdf.

- Drogin EY, Connell M, Foote WE, Sturm CA. The American Psychological Association’s revised “record keeping guidelines”: Implications for the practitioner. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2010;41(3):236. [Google Scholar]

- Gagić S, Tešanović D, Jovičić A. The vital components of restaurant quality that affect guest satisfaction. Turizam. 2013;17(4):166–176. [Google Scholar]

- Grönroos C. A service quality model and its marketing implications. European Journal of Marketing. 1984;18(4):36–44. doi: 10.1108/EUM0000000004784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hannah DR, Lautsch BA. Counting in qualitative research: Why to conduct it, when to avoid it, and when to closet it. Journal of Management Inquiry. 2010;20(1):14–22. doi: 10.1177/1056492610375988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herron AJ, Brennan TK. The ASAM Essentials of Addiction Medicine. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm. A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ladhari R. A review of twenty years of SERVQUAL research. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences. 2009;1(2):172–198. doi: 10.1108/17566690910971445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Meyers K. Contemporary addiction treatment: a review of systems problems for adults and adolescents. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;56(10):764–770. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers K, Cacciola J, Ward S, Kaynak O, Woodworth A. Paving the Way to Change: Advancing Quality Interventions for Adolescents Who Use, Abuse or are Dependent Upon Alcohol and Other Drugs. Philadelphia, PA: TRI; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mohsin Butt M, Cyril de Run E. Private healthcare quality: applying a SERVQUAL model. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance. 2010;23(7):658–673. doi: 10.1108/09526861011071580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrow CA, Murrow J. What makes a good nurse? Marketing Health Services. 2002;22(4):14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Principles of Adolescent Substance Use Disorder Treatment: A Research-Based Guide. 2014 Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/podata_1_17_14.pdf.

- Nix K. What Obamacare’s pay-for-performance programs mean for health care quality. The Heritage Foundation’s Backgrounder. 2013;2856:1–9. Retrieved from https://www.heartland.org/sites/default/files/bg2856.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Ferriter C. Parent management of attendance and adherence in child and adolescent therapy: a conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Child and Family Psychological Review. 2005;8(2):149–166. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-4753-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcross JCE. Psychotherapy relationships that work. 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman A, Berry LL, Zeithaml VA. Service Firms Need Marketing Skills. Business Horizons. 1983;26(6):28–31. doi: 10.1016/0007-6813(83)90043-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman A, Berry LL, Zeithaml VA. Refinement and Reassessment of the Servqual Scale. Journal of Retailing. 1991a;67(4):420–450. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman A, Berry LL, Zeithaml VA. Understanding Customer Expectations of Service. Sloan Management Review. 1991b;32(3):39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman A, Berry LL, Zeithaml VA. More on Improving Service Quality Measurement. Journal of Retailing. 1993;69(1):12–40. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4359(05)80007-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman A, Zeithaml VA, Berry LL. SERVQUAL. Journal of Retailing. 1988;64(1):12–40. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo qualitative data analysis software (Version 10) 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan O, Murphy D, Krom L. Vital Signs: Taking the Pulse of the Addiction Treatment Workforce, A National Report, Version 1. Kansas City, MO: Addiction Technology Transfer Center National Office in residence at the University of Missouri-Kansas City; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health. 1995;18(2):179–183. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofaer S, Firminger K. Patient perceptions of the quality of health services. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:513–559. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.050503.153958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tempier R, Hepp SL, Duncan CR, Rohr B, Hachey K, Mosier K. Patient-centered care in affective, non-affective, and schizoaffective groups: patients’ opinions and attitudes. Community Mental Health Journal. 2010;46(5):452–460. doi: 10.1007/s10597-010-9316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml VA, Bitner MJ, Gremler D. Services marketing: integrating customer focus across the firm. 6. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Higher Education; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zima BT, Murphy JM, Scholle SH, Hoagwood KE, Sachdeva RC, Mangione-Smith R, … Jellinek M. National quality measures for child mental health care: background, progress, and next steps. Pediatrics. 2013;131(Supplement 1):S38–S49. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1427e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]