Abstract

Recent data illustrate a key role for the transcriptional regulator Bach2 in orchestrating T cell differentiation and function. Although Bach2 has a well-described role in B cell differentiation, emerging data show that Bach2 is a prototypical member of a novel class of transcription factors that regulates transcriptional activity in T cells at super enhancers, or regions of high transcriptional activity. Accumulating data demonstrate specific roles for Bach2 in favoring regulatory T cell generation, restraining effector T cell differentiation and potentiating memory T cell development. Evidence suggests that Bach2 regulates various facets of T cell function by repressing other key transcriptional regulator such as Blimp-1. This review examines our current understanding of the role of Bach2 in T cell function and highlights the growing evidence that this transcriptional repressor functions as a key regulator involved in maintenance of T cell quiescence, T cell subset differentiation and memory T cell generation.

Introduction

Significant progress has been made in identifying and delineating the effects of key transcriptional regulators that govern the diverse fates of lymphocytic effector subsets. One such regulator is the transcriptional repressor Bach2. In addition to its well-defined role in B cell and plasma cell differentiation (recently reviewed in (1-3)), Bach2 is emerging as a functionally important regulator of other immune cell types, including macrophages and T cells (4). In this review we discuss our current understanding of the role of Bach2 in regulating T cell development and homeostasis, as well as the emerging role of Bach2 in regulating the differentiation and function of effector and memory T cells. The potential for Bach2 to regulate various states of T cell activation, including quiescence and exhaustion, are also discussed.

Bach2 Basics

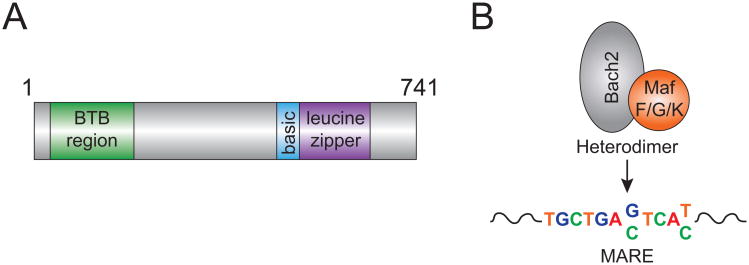

Bach2 is a member of the Bach (bric-a-brac, tramtrack and broad complex and cap n′ collar homology) family of bZip (basic leucine zipper) transcription factors (Fig. 1A). The Bach2 gene is located on human chromosome 6, 6q15 (chromosome 4, 4A4 in mouse) and encodes a 741 amino acid protein whose functional domains are highly conserved (>94%) in mice and humans (5, 6). Bach2 expression was originally described as being confined to the B cell lineage and to some neuronal cells that expressed a neuron-specific splice variant (7). However, Bach2 expression was later identified in the T cell lineage where it was reported to bind the IL-2 promoter and was required for maintenance of IL-2 production by human cord blood CD4+ T cells (8).

Figure 1. Bach2 Basics.

A) Schematic representation of Bach2 protein structure. Broad complex-tamtrack-bric-a-brac (BTB) region, basic region, and leucine zipper are depicted. B) DNA binding motif for Bach2. Muscloaponeurotic fibrosarcoma (Maf), Maf-recognition element (MARE).

The bZip transcription factors characteristically form heterodimers through their leucine zippers with the Maf family of proteins yielding NF-E2 transcription factors (reviewed in (9)). Bach2 forms heterodimers with small Maf proteins including, MafF, MafG, and MafK, allowing binding to Maf-recognition elements (MAREs) with the consensus sequence TGCTGA(G/C)TCA(T/C) (7) (Fig. 1B). Bach2 contains a nuclear localization signal in its Zip domain and a nuclear export signal at its C-terminus. Several factors regulate Bach2 activity and localization (reviewed in (2)), including PI 3-Kinase signaling in B cells, which leads to phosphorylation of Ser512 and cytosolic accumulation. Oxidative stress inhibits the activity of the nuclear export signal and thus leads to nuclear accumulation.

Bach2 function has been most extensively investigated in B cells where it is known to repress expression of Blimp-1 (B-lymphocyte-induced maturation protein 1), also known as PRDM1 (PR domain zinc finger protein), by binding to the MARE 5′ of the prdm1 (Blimp-1) gene (10). Conditional ablation of Bach2 in the B cell lineage has revealed that Bach2 down-regulation is essential not only for Blimp-1 de-repression and differentiation of B cells into plasma cells, but also for class switch recombination leading to IgG1 secretion (11). However, the fates of B cells are not governed simply by Bach2 repression of Blimp-1. Rather, a complex transcription factor network controls memory B cell and plasma cell differentiation and key molecular events concomitant with differentiation, including class switch recombination, somatic hyper-mutation, and Ig secretion (1, 2).

Bach2 in disease

The bach2 gene locus is susceptible to modifications that impact health. Aberrations in the long arm of chromosome 6 are often associated with B cell malignancies. This includes a Bach2-Bcl2LI fusion product detected in a lymphoma line (12). This resulted in enhanced expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl2LI (also known as BCL-XL). In another study, chromosomal rearrangements in an IgH-Myc-positive lymphoma resulted in fusion of exon 1 of IgHCδ on 14q32 to exon 2 of bach2 (13). The fusion transcript spanned the entire coding region (exons 2-9) of bach2, and was highly expressed. Thus, aberrant expression of Bach2 and or its fusion partners is concordant with B cell malignancies, reinforcing the notion that Bach2 critically governs homeostasis in B lymphocytes.

The bach2 locus was shown to be a site of HIV-1 integration in resting CD4+ T cells in patients undergoing retroviral therapy (14). The bach2 locus may therefore constitute part of the mechanism by which patients with HIV infection maintain a reservoir of latently infected T cells. Bach2 expression changes also correlate with some diseases where aberrant T cell function is evident. For example, in patients with celiac disease, IFN-γ expression is strongly up-regulated while Bach2 expression is strongly down-regulated (15). Genome-wide association studies have revealed single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the bach2 gene that are associated with a greater risk for developing rheumatoid arthritis (16), Crohn's disease (17), multiple sclerosis (18), type I diabetes (19), and asthma (20). The bach2 polymorphisms observed were common to more than one disease, but often not equally associated. For example, the rs1847472 SNP was strongly associated with celiac disease, but weakly associated with asthma. Therefore, bach2 polymorphisms are likely important contributors to susceptibility to different diseases, but may have varying importance depending on the immune mechanisms driving pathology.

Bach2 regulation of T cell development and homeostasis

Originally described as a transcriptional regulator of B cells, it is now well appreciated that α/β T cells also express Bach2 (Fig. 2A). Bach2-encoding mRNA has been detected in thymic and peripheral T-lineage cells (21). Bach2 transcription gradually increases as T cells undergo differentiation and selection in the thymus, with more pronounced increases as T cells reach the single positive developmental stage (21). Expression is additionally regulated upon thymic egress, at least in CD8 T cells, as Bach2 mRNA expression further increases in naive CD8 T cells as they seed the periphery (21). The factors regulating the expression of Bach2 in developing and mature T cells remain poorly defined, but TCR crosslinking via antigen encounter may lead to a reduction in Bach2 expression. Consistent with this, antigen-experienced, effector and memory CD4 and CD8 T cells recovered from the periphery express lower levels of Bach2 transcripts, compared to their naïve counterparts (21). As detailed below, cytokine signaling and other extrinsic factors are likely important for modulating Bach2 expression or activity in T cells. Furthermore, the expression of Bach2 is likely to be post-transcriptionally regulated in lymphocytes, as CD4 T cells express lower amounts of Bach2 protein compared to B cells, despite similar abundance of Bach2 transcripts (21). Recent data also established that the epigenetic regulator MENIN promotes Bach2 expression in CD4 T cells via maintenance of histone acetylation at the bach2 locus. This prevents T cell acquisition of potentially damaging senescence-associated secretory phenotype, characterized in part by spontaneous pro-inflammatory cytokine production associated with loss of Bach2 expression (22) and further link Bach2 activity to the maintenance of T cell homeostasis. Delineating the mechanisms that govern Bach2 transcription and post-transcriptional regulation in T cells as they develop, mature, undergo homeostatic proliferation and respond to infection will be critical to further elucidate the biological role and function of Bach2 in scenarios of both health and disease.

Figure 2. Bach2 expression in T cells and its role in CD4 T cell subset differentiation.

A) Bach2 mRNA expression increases as T cells differentiate and mature into single positive T cells in the thymus. Once in the periphery, Bach2 mRNA expression declines when T cells are activated and develop into effector T cells. Expression profiles in phenotypically and functionally distinct memory T cell subsets are unknown. B) Bach2 expression promotes Treg differentiation, whereas Bach2 suppresses factors involved in Th1, Th2 and Th17 subset formation. The role of Bach2 in Tfh and Th9 development and differentiation remains to be elucidated.

T cell expression of Bach2 is critical for the generation of T regulatory (Treg) cells. bach2-/- mice develop a progressive wasting disease, marked by an increased presence of anti-nuclear antibodies associated with severely decreased numbers of Foxp3+ Tregs (23, 24). Expression of Bach2 may also be important for regulating the function of Tregs, as the limited number of Tregs recovered from bach2-/- mice exhibited a terminally differentiated phenotype and were unable to prevent disease in a T cell adoptive transfer model of colitis (23, 24). Bach2 also regulates the formation of peripherally induced Tregs (iTregs). The absence of Bach2 severely abrogated the generation of iTregs following activation in the presence of TGF-β, instead yielding activated T cells expressing a number of genes associated with other functionally distinct CD4 T cell subsets (23, 24). This includes a number of genes associated with T helper (Th) lineage commitment such as GATA-3, T-bet and RORγt. Thus, Bach2 may serve to allow for iTreg differentiation by preventing the expression of other key regulators of effector T cell differentiation. Intriguingly, Bach2 may also function differentially depending on the T cell developmental stage or maturation checkpoint, as Bach2 serves as a transcriptional inducer of IL-2 in human cord blood CD4 T cells (8). The factors that determine reported differential functions of Bach2 in CD4 T cells, and whether the functional impacts of Bach2 depend on the developmental stage of T cells, currently remain unknown and warrant further investigation.

Bach2 regulation of effector T cell differentiation and activity

Functionally distinct subsets of T cells regulate various aspects of immunologic protection against microbial infections, humoral immunity and autoimmune pathogenesis. In addition to Tregs, emerging data support the concept that Bach2 plays a critical role in regulating the differentiation of functionally distinct effector T cells (Fig. 2B). A recent study identified Bach2 as the potential first member of a novel class of transcriptional repressors that limit transcriptional activity at genomic loci referred to as super enhancers (SE) (25). SE are regions of enhanced transcriptional activity that are postulated to play essential roles in establishment of the functional identity of T cell lineages and subsets (26). For example, in peripheral T cells, SE regions are typically associated with genes that regulate lineage-specific cytokine responses (25). These include cytokine or cytokine receptor genes such as Ifng, Il17a,f and Il4ra as well as lineage determining transcription factor genes such as tbx21 (T-bet), gata3 (GATA-3) and rorc (RORγt) (25). Thus, as a repressor of transcription at SE regions, Bach2 can

profoundly suppress the development and polarization of functional T cell responses. In support of this, while Bach2 is not required for T cell development in the thymus, it appears required to maintain quiescence of naïve T cells in the periphery (21). Indeed, specific deletion of Bach2 in T cells leads to a spontaneous decrease in the number of phenotypically naïve CD4 T cells (based on CD62Lhi and CD44lo expression patterns) and an increase of CD62L-negative cells that exhibit transcriptional profiles resembling those of effector memory T cells, in the absence of any pathogenic challenge (21). While these data strongly support the idea that Bach2 functions to maintain T cell quiescence in the periphery, it is important to note that bach2-/-, CD62L-negative T cells did not develop into bona fide, functional antigen-specific effector memory T cells, as evidenced by their low expression of CD44. In addition, despite their activated phenotype, bach2-/- T cells were less efficient than WT cells in protecting the host from Listeria monocytogenes infection or inducing colitis following transfer into rag1-/- recipient mice (21). Thus, bach2-/- T cells may not acquire full effector function, despite their activated phenotype. Rather, T cells lacking Bach2 appear to spontaneously develop an activated phenotype independently of antigenic encounter, suggesting that Bach2 actively restrains T cell activation at steady-state or during homeostatic, cytokine-driven turnover and maintenance. Thus, while Bach2 restrains T cell activation at steady-state, its absence is insufficient for T cells to develop the functional advantages and heightened protective capacity associated with effector or memory T cells.

In further support of the role of Bach2 as a regulator of T cell subset differentiation, bach2-/- CD4 T cells exhibited enhanced Th2 differentiation and enhanced Th2-associated cytokine expression (21). Notably, enhanced Th2 differentiation among bach2-/- CD4 T cells was apparent even in the presence of Th1-promoting cytokines that normally restrain Th2 differentiation, including IL-12 (21). One explanation for these observations is the capacity of Bach2 to suppress multiple genes that are linked to Th2 differentiation and function, including the transcription factor Blimp-1, which can potently suppress Th1 gene expression profiles (21, 27, 28). Thus, Bach2 can act as an important transcriptional regulator that facilitates CD4 T cell differentiation towards a Th1 phenotype and function via suppression of Th2 transcriptional programs. Similarly, Bach2 can restrain Th17 differentiation, potentially through the repression of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Ahr) (24), as Ahr ligands strongly promote Th17 differentiation (29). While the factors that regulate the expression of Bach2 to favor differentiation towards the various T helper subsets remain undefined, the key role for cytokines in dictating CD4 T cell subset differentiation strongly suggests that cytokines may also be involved in Bach2 regulation. It will be of tremendous interest to delineate how Bach2 expression is regulated during the course of T cell activation and to determine potential context-specific roles of Bach2 in the differentiation of functionally distinct CD4 T cells subsets, including other key CD4 subsets such as T follicular helper (Tfh) and Th9 cells.

The Tfh cell subset is essential for orchestrating the germinal center reaction, affinity maturation, immunoglobulin class-switching and the generation of memory B cells. Bcl-6 is identified as a key regulator of Tfh development and function, and similar to Bach2, Bcl-6 can function to suppress Blimp-1, an antagonist of both Th1 and Tfh development. Given the parallels between Bcl-6 and Bach2 in suppressing Blimp-1 expression, and the key role of Blimp-1 in repressing Tfh differentiation (30), it is interesting to speculate that Bach2 and Bcl-6 independently, simultaneously, or coordinately function to govern Tfh cell development. Indeed, at least in B cells, there is precedent for complex formation between Bach2 and Bcl-6 during repression of the promoter of prdm-1, the gene encoding Blimp-1 (31). Further work is required to dissect the specific contributions of Bach2 in regulating Tfh development, commitment and activity.

Accumulating data support the idea that Bach2 also exerts profound effects on the function of fully differentiated, mature T cells. As noted above, studies show that bach2-/- mature T cells express significantly elevated levels of the Th2-associated cytokine IL-4 following activation compared to wild type counterparts (21). These data are consistent with a role for Bach2 in limiting T cell activation and function. On the other hand, studies of bach2-/- Tregs reveal markedly impaired chemokine receptor expression, which may explain why Bach2-deficient Tregs can still suppress effector T cells in vitro (23), but bach2-/- Tregs fail to limit colitis in the naïve CD4 T cell transfer models of colitis (23) or infiltrate tumors (32). Thus, although bach2-/- T cells generally exhibit enhanced effector function, loss or down-regulation of Bach2 in T cells may limit their capacity to efficiently traffic to sites of inflammation or infection. More studies are required to fully elucidate the role of Bach2 in regulating T cell homing, trafficking, and functional activities that extend beyond elaboration of cytokines during health and disease.

Bach2 regulation of memory T cell development and function

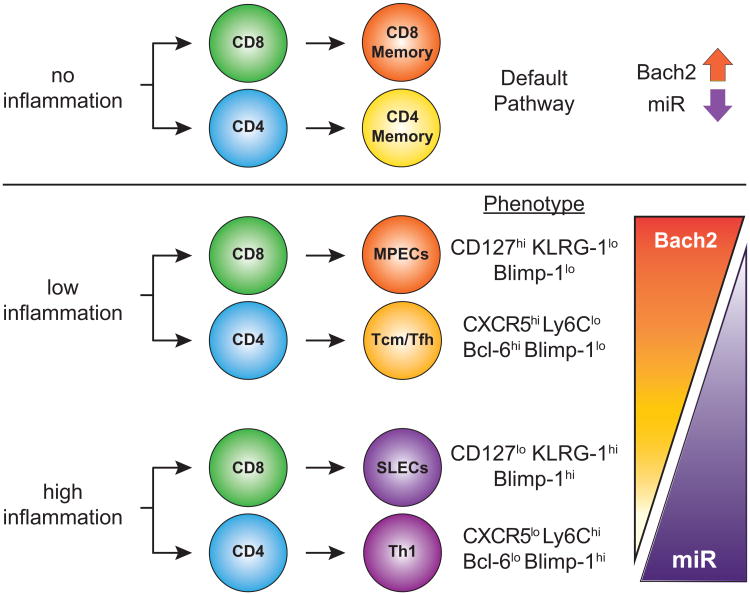

Recent studies are establishing an important role for Bach2 in shaping the development and biology of memory T cells (Fig. 3). Using bioinformatics approaches, Hu and Chen (33) mined 386 publicly deposited gene expression databases detailing the transcriptional profiles of CD8 T cells in different states of activation. This analysis led to the identification of a number of transcription factors not previously associated with memory CD8 T cell memory generation, including Bach2 (33). The biological and functional relevance of Bach2 in memory T cell progression was demonstrated by retroviral-mediated transduction of Bach2 in CD8 T cells, which resulted in increases in the number of CD8 T cells at the peak of the response as well as increased survival during the contraction phase to establish memory populations (33). Similarly, Restifo and colleagues (34) recently demonstrated that bach2-/- CD8 T cells fail to accumulate or form numerically stable memory pools after acute viral infection. In addition, they demonstrated that Bach2 restrains CD8 T cell effector differentiation by interfering with the function of a subset of activator protein-1 (AP-1) family transcription factors (34). Together, these genetic studies confirm that Bach2 is functionally linked to the establishment of memory potential in T cells.

Figure 3. Postulated role of Bach2 in T cell memory progression.

In the absence of inflammatory cytokine signalling, antigen-activated T cells default towards memory T cell progression. Low inflammatory conditions also bias T cells towards a memory phenotype, whereas high systemic inflammatory events divert T cells towards an effector phenotype. The role of Bach2 in these processes and its modulation by inflammation-induced microRNA expression remain to be elucidated. Short-lived effector cells (SLEC), memory precursor effector cells (MPEC), and microRNA (miR).

Although the transcriptional networks governing the induction and effects of Bach2 on memory T cell development have not been fully elucidated, repression of Blimp-1 expression by Bach2 is likely a critical component of the mechanism by which Bach2 promotes memory T cell formation. Blimp-1 expression is required for the differentiation of short lived effector cells and Blimp-1 deficiency favors the development of memory T cells (35, 36). Indeed, Blimp-1 deficiency in T cells promotes the acquisition of memory characteristics among effector T cell populations (36). Thus, Bach2-mediated enhancement of memory CD8 T cell generation is likely linked to its capacity to down-regulate the expression of genes associated with effector differentiation thereby tipping the balance in favor of generating memory cells earlier in the response. This is supported by recent data demonstrating that Bach 2 can compete with AP-1 family transcription factors to prevent the induction of the effector transcriptional program in CD8 T cells (34). Notably XBP-1, which is classically regarded as a critical regulator of antibody secretion by B cells (37, 38), has also been linked to promoting the terminal differentiation of T cells via activation of ER stress (39). In B cells, the transcriptional control circuit of XBP-1 splicing and activation is in turn regulated by Blimp-1, whose activity is further repressed by Bach2. It is therefore likely that many of the same transcriptional networks operating in B cells also impact the fate, function and survival of effector and memory T cells. Given the intimate functional links between the activity of Bach2 and the expression and function of Blimp-1, it is plausible that Bach2 functions upstream of pathways that promote the formation and maintenance of long-lived T cell immunity following infection or vaccination.

The development of memory characteristics in CD8 T cells has been postulated to represent a default pathway that gets diverted toward effector CD8 T cell development and acquisition of effector function by inflammatory cytokines (40) (Fig. 3). Recent data show that specific inflammatory cytokines and innate signals, including IL-12/IL-18 or IL-15, and TLR signaling, promote microRNA (miRNA) miR-181a and miR-148a expression in human and murine leukocytes (41, 42) and miR-148a has been shown to directly limit Bach2 expression (43). Altered regulation of Bach2 may function as a mechanistic link by which specific inflammatory cytokines and miRNA regulate T cell differentiation, survival and memory formation. Consistent with this hypothesis, overexpression of miR-181a in T cells enhances expression of co-stimulatory molecules and potentiates calcium flux following TCR crosslinking (44). Both the quality and duration of TCR signaling regulate memory T cell progression (45-48). Thus, miRNA-mediated gene regulation represents a critical additional level of post-transcriptional genetic control with profound effects on gene expression in immune cells. Moreover, the cytokine-induced activity of specific miRNAs targeting Bach2 would also be consistent with data demonstrating that Bach2 expression is post-transcriptionally regulated in distinct lymphocyte subsets (21). It is possible that Bach2 actively suppresses T cell effector functions (favoring the “default” memory pathway) and that T cell exposure to inflammatory cytokines is required to reduce its expression allowing for the establishment of T cell transcriptional effector programs and enhanced effector function. Collectively, these studies further support the hypothesis that Bach2 functions at the nexus of a critical transcriptional network that governs effector and memory T cell differentiation, activity and survival.

Bach2 as a potential regulator of T cell exhaustion?

Following acute infection or vaccination, antigen-specific T cell populations undergo proliferative expansion, acquire and exert effector functions, and subsequently undergo numerical contraction leaving pools of memory T cells that afford the host enhanced protection against re-infection. (49). Similarly, T cells responding to chronic infections in which the pathogen is not efficiently eliminated also undergo similar phases of expansion and contraction. However, unlike scenarios of acute infection or vaccination, T cells responding to persistent infection exhibit specific alterations in gene expression profiles that are associated with functional impairments, including loss of cytokine expression, reduced T helper and cytolytic potential, and increased rates of apoptosis (50, 51). These biological processes are collectively known as T cell exhaustion, which is phenotypically, functionally, and molecularly distinct from T cell anergy or senescence (reviewed in (52)). The molecular mechanisms responsible for T exhaustion are multifactorial and include perturbations in the transcriptional programming of T cells.

Regarding altered expression and function of transcription factor networks, Eomes (53), T-bet (54), and Blimp-1 (55) promote T cell exhaustion, whereas Id3 (56) limits T cell terminal differentiation and exhaustion. Given the capacity for Bach2 to regulate these transcription factor networks, it is tempting to speculate that Bach2 may critically govern T cell exhaustion. In support of this hypothesis, recent profiling studies of exhausted CD4 and CD8 T cells responding to chronic viral infection showed that Bach2 expression is reduced 2-4 fold compared to conventional (i.e. ‘functional’) memory CD4 and CD8 T cell subsets (57). Repeated TCR stimulation may also be important for potential reductions in Bach2 expression in T cells responding to chronic infection or persistent antigen. As noted above, effector and memory T cells express relatively reduced Bach2 compared to naïve T cells (33), and as T cells are driven through sequentially progressive recall responses to generate secondary, tertiary and quaternary memory cells, Bach2 expression is proportionately reduced (58). Interestingly, these multiply stimulated memory T cells maintain a more effector-like profile, suggesting that this may be controlled by progressive loss of Bach2 following repeated TCR triggering. As a composite, these data are consistent with an important mechanistic role for Bach2 in limiting terminal differentiation of T cells, preventing T cell exhaustion, and promoting long-lived, numerically and functionally stable populations of memory T cells.

Conclusions

T cells are essential for providing protection against intracellular pathogens and orchestrating humoral immunity. Conversely, T cells can also be pathologic, driving autoimmune disease, allergy or atopy. Thus, understanding the molecular mechanisms that govern the development, differentiation, and function of antigen-specific T cells remains a critically important goal. Bach2 is emerging as a fundamentally important molecular ‘switch’ that can limit terminal differentiation of T cells, constrain their functional activity, potentially promoting the generation of long-lived, highly functional memory T cell populations. Despite this, little is known about the pathways that regulate Bach2 expression in T cells. It will be of significant interest to determine whether Bach2 is mechanistically linked to limiting or preventing T cell exhaustion or senescence. Discovering new circuits of molecular control of T cell differentiation, function and memory formation will facilitate the development of new approaches to maintain immune homeostasis, limit pathological T cells responses, and enhance T cell vaccine-induced protective immunity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. S.A. Condotta (McGill University, Montreal, Quebec) for generating the figures and Drs. L. Thompson (Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Oklahoma City), C. Webb (University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City), and S.A. Condotta for critical reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations used in this article

- AP-1

activator protein-1

- Bach

bric-a-brac, tramtrack and broad complex and cap n′ collar homology

- Blimp-1

B-lymphocyte-induced maturation protein 1

- bZip

basic leucine zipper

- iTreg

peripherally induced regulatory T cell

- MARE

Maf-recognition elements

- miRNA

microRNA

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- Treg

regulatory T cell

- Tfh

T follicular helper

Footnotes

M.J.R. is supported by funds from the Canada Foundation for Innovation (JELF) and from the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RGPIN-2016-04713). N.S.B. is supported by grants from the NIH/NIAID (AI125446) and the NIH/NIGMS (GM103447). M.L.L. is supported by grants from the NIH/NIAID (AI078993) and the Presbyterian Health Foundation of Oklahoma City.

References

- 1.Igarashi K, Ochiai K, Itoh-Nakadai A, Muto A. Orchestration of plasma cell differentiation by Bach2 and its gene regulatory network. Immunological reviews. 2014;261:116–125. doi: 10.1111/imr.12201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Igarashi K, Ochiai K, Muto A. Architecture and dynamics of the transcription factor network that regulates B-to-plasma cell differentiation. Journal of biochemistry. 2007;141:783–789. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nutt SL, Taubenheim N, Hasbold J, Corcoran LM, Hodgkin PD. The genetic network controlling plasma cell differentiation. Seminars in immunology. 2011;23:341–349. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou Y, Wu H, Zhao M, Chang C, Lu Q. The Bach Family of Transcription Factors: A Comprehensive Review. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s12016-016-8538-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sykiotis GP, Bohmann D. Stress-activated cap‘n’collar transcription factors in aging and human disease. Science signaling. 2010;3:re3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3112re3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sasaki S, Ito E, Toki T, Maekawa T, Kanezaki R, Umenai T, Muto A, Nagai H, Kinoshita T, Yamamoto M, Inazawa J, Taketo MM, Nakahata T, Igarashi K, Yokoyama M. Cloning and expression of human B cell-specific transcription factor BACH2 mapped to chromosome 6q15. Oncogene. 2000;19:3739–3749. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oyake T, Itoh K, Motohashi H, Hayashi N, Hoshino H, Nishizawa M, Yamamoto M, Igarashi K. Bach proteins belong to a novel family of BTB-basic leucine zipper transcription factors that interact with MafK and regulate transcription through the NF-E2 site. Molecular and cellular biology. 1996;16:6083–6095. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lesniewski ML, Haviernik P, Weitzel RP, Kadereit S, Kozik MM, Fanning LR, Yang YC, Hegerfeldt Y, Finney MR, Ratajczak MZ, Greco N, Paul P, Maciejewski J, Laughlin MJ. Regulation of IL-2 expression by transcription factor BACH2 in umbilical cord blood CD4+ T cells. Leukemia. 2008;22:2201–2207. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blank V. Small Maf proteins in mammalian gene control: mere dimerization partners or dynamic transcriptional regulators? Journal of molecular biology. 2008;376:913–925. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ochiai K, Katoh Y, Ikura T, Hoshikawa Y, Noda T, Karasuyama H, Tashiro S, Muto A, Igarashi K. Plasmacytic transcription factor Blimp-1 is repressed by Bach2 in B cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:38226–38234. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607592200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kometani K, Nakagawa R, Shinnakasu R, Kaji T, Rybouchkin A, Moriyama S, Furukawa K, Koseki H, Takemori T, Kurosaki T. Repression of the transcription factor Bach2 contributes to predisposition of IgG1 memory B cells toward plasma cell differentiation. Immunity. 2013;39:136–147. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turkmen S, Riehn M, Klopocki E, Molkentin M, Reinhardt R, Burmeister T. A BACH2-BCL2L1 fusion gene resulting from a t(6;20)(q15;q11.2) chromosomal translocation in the lymphoma cell line BLUE-1. Genes, chromosomes & cancer. 2011;50:389–396. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi S, Taki T, Chinen Y, Tsutsumi Y, Ohshiro M, Kobayashi T, Matsumoto Y, Kuroda J, Horiike S, Nishida K, Taniwaki M. Identification of IGHCdelta-BACH2 fusion transcripts resulting from cryptic chromosomal rearrangements of 14q32 with 6q15 in aggressive B-cell lymphoma/leukemia. Genes, chromosomes & cancer. 2011;50:207–216. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikeda T, Shibata J, Yoshimura K, Koito A, Matsushita S. Recurrent HIV-1 integration at the BACH2 locus in resting CD4+ T cell populations during effective highly active antiretroviral therapy. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2007;195:716–725. doi: 10.1086/510915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quinn EM, Coleman C, Molloy B, Dominguez Castro P, Cormican P, Trimble V, Mahmud N, Mc Manus R. Transcriptome Analysis of CD4+ T Cells in Coeliac Disease Reveals Imprint of BACH2 and IFNgamma Regulation. PloS one. 2015;10:e0140049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McAllister K, Yarwood A, Bowes J, Orozco G, Viatte S, Diogo D, Hocking LJ, Steer S, Wordsworth P, Wilson AG, Morgan AW, Kremer JM, Pappas D, Gregersen P, Klareskog L, Plenge R, Barton A, Greenberg J, Worthington J, Eyre S. Identification of BACH2 and RAD51B as rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility loci in a meta-analysis of genome-wide data. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2013;65:3058–3062. doi: 10.1002/art.38183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franke A, McGovern DP, Barrett JC, Wang K, Radford-Smith GL, Ahmad T, Lees CW, Balschun T, Lee J, Roberts R, Anderson CA, Bis JC, Bumpstead S, Ellinghaus D, Festen EM, Georges M, Green T, Haritunians T, Jostins L, Latiano A, Mathew CG, Montgomery GW, Prescott NJ, Raychaudhuri S, Rotter JI, Schumm P, Sharma Y, Simms LA, Taylor KD, Whiteman D, Wijmenga C, Baldassano RN, Barclay M, Bayless TM, Brand S, Buning C, Cohen A, Colombel JF, Cottone M, Stronati L, Denson T, De Vos M, D'Inca R, Dubinsky M, Edwards C, Florin T, Franchimont D, Gearry R, Glas J, Van Gossum A, Guthery SL, Halfvarson J, Verspaget HW, Hugot JP, Karban A, Laukens D, Lawrance I, Lemann M, Levine A, Libioulle C, Louis E, Mowat C, Newman W, Panes J, Phillips A, Proctor DD, Regueiro M, Russell R, Rutgeerts P, Sanderson J, Sans M, Seibold F, Steinhart AH, Stokkers PC, Torkvist L, Kullak-Ublick G, Wilson D, Walters T, Targan SR, Brant SR, Rioux JD, D'Amato M, Weersma RK, Kugathasan S, Griffiths AM, Mansfield JC, Vermeire S, Duerr RH, Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Schreiber S, Cho JH, Annese V, Hakonarson H, Daly MJ, Parkes M. Genome-wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of confirmed Crohn's disease susceptibility loci. Nature genetics. 2010;42:1118–1125. doi: 10.1038/ng.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sawcer S, Hellenthal G, Pirinen M, Spencer CC, Patsopoulos NA, Moutsianas L, Dilthey A, Su Z, Freeman C, Hunt SE, Edkins S, Gray E, Booth DR, Potter SC, Goris A, Band G, Oturai AB, Strange A, Saarela J, Bellenguez C, Fontaine B, Gillman M, Hemmer B, Gwilliam R, Zipp F, Jayakumar A, Martin R, Leslie S, Hawkins S, Giannoulatou E, D'Alfonso S, Blackburn H, Martinelli Boneschi F, Liddle J, Harbo HF, Perez ML, Spurkland A, Waller MJ, Mycko MP, Ricketts M, Comabella M, Hammond N, Kockum I, McCann OT, Ban M, Whittaker P, Kemppinen A, Weston P, Hawkins C, Widaa S, Zajicek J, Dronov S, Robertson N, Bumpstead SJ, Barcellos LF, Ravindrarajah R, Abraham R, Alfredsson L, Ardlie K, Aubin C, Baker A, Baker K, Baranzini SE, Bergamaschi L, Bergamaschi R, Bernstein A, Berthele A, Boggild M, Bradfield JP, Brassat D, Broadley SA, Buck D, Butzkueven H, Capra R, Carroll WM, Cavalla P, Celius EG, Cepok S, Chiavacci R, Clerget-Darpoux F, Clysters K, Comi G, Cossburn M, Cournu-Rebeix I, Cox MB, Cozen W, Cree BA, Cross AH, Cusi D, Daly MJ, Davis E, de Bakker PI, Debouverie M, D'Hooghe M B, Dixon K, Dobosi R, Dubois B, Ellinghaus D, Elovaara I, Esposito F, Fontenille C, Foote S, Franke A, Galimberti D, Ghezzi A, Glessner J, Gomez R, Gout O, Graham C, Grant SF, Guerini FR, Hakonarson H, Hall P, Hamsten A, Hartung HP, Heard RN, Heath S, Hobart J, Hoshi M, Infante-Duarte C, Ingram G, Ingram W, Islam T, Jagodic M, Kabesch M, Kermode AG, Kilpatrick TJ, Kim C, Klopp N, Koivisto K, Larsson M, Lathrop M, Lechner-Scott JS, Leone MA, Leppa V, Liljedahl U, Bomfim IL, Lincoln RR, Link J, Liu J, Lorentzen AR, Lupoli S, Macciardi F, Mack T, Marriott M, Martinelli V, Mason D, Mc Cauley JL, Mentch F, Mero IL, Mihalova T, Montalban X, Mottershead J, Myhr KM, Naldi P, Ollier W, Page A, Palotie A, Pelletier J, Piccio L, Pickersgill T, Piehl F, Pobywajlo S, Quach HL, Ramsay PP, Reunanen M, Reynolds R, Rioux JD, Rodegher M, Roesner S, Rubio JP, Ruckert IM, Salvetti M, Salvi E, Santaniello A, Schaefer CA, Schreiber S, Schulze C, Scott RJ, Sellebjerg F, Selmaj KW, Sexton D, Shen L, Simms-Acuna B, Skidmore S, Sleiman PM, Smestad C, Sorensen PS, Sondergaard HB, Stankovich J, Strange RC, Sulonen AM, Sundqvist E, Syvanen AC, Taddeo F, Taylor B, Blackwell JM, Tienari P, Bramon E, Tourbah A, Brown MA, Tronczynska E, Casas JP, Tubridy N, Corvin A, Vickery J, Jankowski J, Villoslada P, Markus HS, Wang K, Mathew CG, Wason J, Palmer CN, Wichmann HE, Plomin R, Willoughby E, Rautanen A, Winkelmann J, Wittig M, Trembath RC, Yaouanq J, Viswanathan AC, Zhang H, Wood NW, Zuvich R, Deloukas P, Langford C, Duncanson A, Oksenberg JR, Pericak-Vance MA, Haines JL, Olsson T, Hillert J, Ivinson AJ, De Jager PL, Peltonen L, Stewart GJ, Hafler DA, Hauser SL, Mc Vean G, Donnelly P, Compston A. Genetic risk and a primary role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms in multiple sclerosis. Nature. 2011;476:214–219. doi: 10.1038/nature10251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper JD, Smyth DJ, Smiles AM, Plagnol V, Walker NM, Allen JE, Downes K, Barrett JC, Healy BC, Mychaleckyj JC, Warram JH, Todd JA. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association study data identifies additional type 1 diabetes risk loci. Nature genetics. 2008;40:1399–1401. doi: 10.1038/ng.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferreira MA, Matheson MC, Duffy DL, Marks GB, Hui J, Le Souef P, Danoy P, Baltic S, Nyholt DR, Jenkins M, Hayden C, Willemsen G, Ang W, Kuokkanen M, Beilby J, Cheah F, de Geus EJ, Ramasamy A, Vedantam S, Salomaa V, Madden PA, Heath AC, Hopper JL, Visscher PM, Musk B, Leeder SR, Jarvelin MR, Pennell C, Boomsma DI, Hirschhorn JN, Walters H, Martin NG, James A, Jones G, Abramson MJ, Robertson CF, Dharmage SC, Brown MA, Montgomery GW, Thompson PJ. Identification of IL6R and chromosome 11q13.5 as risk loci for asthma. Lancet. 2011;378:1006–1014. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60874-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsukumo S, Unno M, Muto A, Takeuchi A, Kometani K, Kurosaki T, Igarashi K, Saito T. Bach2 maintains T cells in a naive state by suppressing effector memory-related genes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:10735–10740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306691110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuwahara M, Suzuki J, Tofukuji S, Yamada T, Kanoh M, Matsumoto A, Maruyama S, Kometani K, Kurosaki T, Ohara O, Nakayama T, Yamashita M. The Menin-Bach2 axis is critical for regulating CD4 T-cell senescence and cytokine homeostasis. Nature communications. 2014;5:3555. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim EH, Gasper DJ, Lee SH, Plisch EH, Svaren J, Suresh M. Bach2 regulates homeostasis of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells and protects against fatal lung disease in mice. J Immunol. 2014;192:985–995. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roychoudhuri R, Hirahara K, Mousavi K, Clever D, Klebanoff CA, Bonelli M, Sciume G, Zare H, Vahedi G, Dema B, Yu Z, Liu H, Takahashi H, Rao M, Muranski P, Crompton JG, Punkosdy G, Bedognetti D, Wang E, Hoffmann V, Rivera J, Marincola FM, Nakamura A, Sartorelli V, Kanno Y, Gattinoni L, Muto A, Igarashi K, O'Shea JJ, Restifo NP. BACH2 represses effector programs to stabilize T(reg)-mediated immune homeostasis. Nature. 2013;498:506–510. doi: 10.1038/nature12199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vahedi G, Kanno Y, Furumoto Y, Jiang K, Parker SC, Erdos MR, Davis SR, Roychoudhuri R, Restifo NP, Gadina M, Tang Z, Ruan Y, Collins FS, Sartorelli V, O'Shea JJ. Super-enhancers delineate disease-associated regulatory nodes in T cells. Nature. 2015;520:558–562. doi: 10.1038/nature14154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Witte S, O'Shea JJ, Vahedi G. Super-enhancers: Asset management in immune cell genomes. Trends in immunology. 2015;36:519–526. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kallies A, Hawkins ED, Belz GT, Metcalf D, Hommel M, Corcoran LM, Hodgkin PD, Nutt SL. Transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 is essential for T cell homeostasis and self-tolerance. Nature immunology. 2006;7:466–474. doi: 10.1038/ni1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martins GA, Cimmino L, Shapiro-Shelef M, Szabolcs M, Herron A, Magnusdottir E, Calame K. Transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 regulates T cell homeostasis and function. Nature immunology. 2006;7:457–465. doi: 10.1038/ni1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veldhoen M, Hirota K, Westendorf AM, Buer J, Dumoutier L, Renauld JC, Stockinger B. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor links TH17-cell-mediated autoimmunity to environmental toxins. Nature. 2008;453:106–109. doi: 10.1038/nature06881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rai D, Pham NL, Harty JT, Badovinac VP. Tracking the total CD8 T cell response to infection reveals substantial discordance in magnitude and kinetics between inbred and outbred hosts. J Immunol. 2009;183:7672–7681. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ochiai K, Muto A, Tanaka H, Takahashi S, Igarashi K. Regulation of the plasma cell transcription factor Blimp-1 gene by Bach2 and Bcl6. International immunology. 2008;20:453–460. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roychoudhuri R, Eil RL, Clever D, Klebanoff CA, Sukumar M, Grant FM, Yu Z, Mehta G, Liu H, Jin P, Ji Y, Palmer DC, Pan JH, Chichura A, Crompton JG, Patel SJ, Stroncek D, Wang E, Marincola FM, Okkenhaug K, Gattinoni L, Restifo NP. The transcription factor BACH2 promotes tumor immunosuppression. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2016;126:599–604. doi: 10.1172/JCI82884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu G, Chen J. A genome-wide regulatory network identifies key transcription factors for memory CD8(+) T-cell development. Nature communications. 2013;4:2830. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roychoudhuri R, Clever D, Li P, Wakabayashi Y, Quinn KM, Klebanoff CA, Ji Y, Sukumar M, Eil RL, Yu Z, Spolski R, Palmer DC, Pan JH, Patel SJ, Macallan DC, Fabozzi G, Shih HY, Kanno Y, Muto A, Zhu J, Gattinoni L, O'Shea JJ, Okkenhaug K, Igarashi K, Leonard WJ, Restifo NP. BACH2 regulates CD8 T cell differentiation by controlling access of AP-1 factors to enhancers. Nature immunology. 2016 doi: 10.1038/ni.3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kallies A, Xin A, Belz GT, Nutt SL. Blimp-1 transcription factor is required for the differentiation of effector CD8(+) T cells and memory responses. Immunity. 2009;31:283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rutishauser RL, Martins GA, Kalachikov S, Chandele A, Parish IA, Meffre E, Jacob J, Calame K, Kaech SM. Transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 promotes CD8(+) T cell terminal differentiation and represses the acquisition of central memory T cell properties. Immunity. 2009;31:296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calfon M, Zeng H, Urano F, Till JH, Hubbard SR, Harding HP, Clark SG, Ron D. IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature. 2002;415:92–96. doi: 10.1038/415092a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reimold AM, Iwakoshi NN, Manis J, Vallabhajosyula P, Szomolanyi-Tsuda E, Gravallese EM, Friend D, Grusby MJ, Alt F, Glimcher LH. Plasma cell differentiation requires the transcription factor XBP-1. Nature. 2001;412:300–307. doi: 10.1038/35085509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kamimura D, Bevan MJ. Endoplasmic reticulum stress regulator XBP-1 contributes to effector CD8+ T cell differentiation during acute infection. J Immunol. 2008;181:5433–5441. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pham NL, Badovinac VP, Harty JT. A default pathway of memory CD8 T cell differentiation after dendritic cell immunization is deflected by encounter with inflammatory cytokines during antigen-driven proliferation. J Immunol. 2009;183:2337–2348. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Presnell SR, Al-Attar A, Cichocki F, Miller JS, Lutz CT. Human natural killer cell microRNA: differential expression of MIR181A1B1 and MIR181A2B2 genes encoding identical mature microRNAs. Genes and immunity. 2015;16:89–98. doi: 10.1038/gene.2014.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu X, Zhan Z, Xu L, Ma F, Li D, Guo Z, Li N, Cao X. MicroRNA-148/152 impair innate response and antigen presentation of TLR-triggered dendritic cells by targeting CaMKIIalpha. J Immunol. 2010;185:7244–7251. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Porstner M, Winkelmann R, Daum P, Schmid J, Pracht K, Corte-Real J, Schreiber S, Haftmann C, Brandl A, Mashreghi MF, Gelse K, Hauke M, Wirries I, Zwick M, Roth E, Radbruch A, Wittmann J, Jack HM. miR-148a promotes plasma cell differentiation and targets the germinal center transcription factors Mitf and Bach2. European journal of immunology. 2015;45:1206–1215. doi: 10.1002/eji.201444637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li QJ, Chau J, Ebert PJ, Sylvester G, Min H, Liu G, Braich R, Manoharan M, Soutschek J, Skare P, Klein LO, Davis MM, Chen CZ. miR-181a is an intrinsic modulator of T cell sensitivity and selection. Cell. 2007;129:147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith-Garvin JE, Burns JC, Gohil M, Zou T, Kim JS, Maltzman JS, Wherry EJ, Koretzky GA, Jordan MS. T-cell receptor signals direct the composition and function of the memory CD8+ T-cell pool. Blood. 2010;116:5548–5559. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-292748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teixeiro E, Daniels MA, Hamilton SE, Schrum AG, Bragado R, Jameson SC, Palmer E. Different T cell receptor signals determine CD8+ memory versus effector development. Science. 2009;323:502–505. doi: 10.1126/science.1163612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caserta S, Kleczkowska J, Mondino A, Zamoyska R. Reduced functional avidity promotes central and effector memory CD4 T cell responses to tumor-associated antigens. J Immunol. 2010;185:6545–6554. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Catron DM, Rusch LK, Hataye J, Itano AA, Jenkins MK. CD4+ T cells that enter the draining lymph nodes after antigen injection participate in the primary response and become central-memory cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2006;203:1045–1054. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Youngblood B, Hale JS, Ahmed R. T-cell memory differentiation: insights from transcriptional signatures and epigenetics. Immunology. 2013;139:277–284. doi: 10.1111/imm.12074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moskophidis D, Lechner F, Pircher H, Zinkernagel RM. Virus persistence in acutely infected immunocompetent mice by exhaustion of antiviral cytotoxic effector T cells. Nature. 1993;362:758–761. doi: 10.1038/362758a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zajac AJ, Blattman JN, Murali-Krishna K, Sourdive DJ, Suresh M, Altman JD, Ahmed R. Viral immune evasion due to persistence of activated T cells without effector function. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1998;188:2205–2213. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crespo J, Sun H, Welling TH, Tian Z, Zou W. T cell anergy, exhaustion, senescence, and stemness in the tumor microenvironment. Current opinion in immunology. 2013;25:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paley MA, Kroy DC, Odorizzi PM, Johnnidis JB, Dolfi DV, Barnett BE, Bikoff EK, Robertson EJ, Lauer GM, Reiner SL, Wherry EJ. Progenitor and terminal subsets of CD8+ T cells cooperate to contain chronic viral infection. Science. 2012;338:1220–1225. doi: 10.1126/science.1229620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kao C, Oestreich KJ, Paley MA, Crawford A, Angelosanto JM, Ali MA, Intlekofer AM, Boss JM, Reiner SL, Weinmann AS, Wherry EJ. Transcription factor T-bet represses expression of the inhibitory receptor PD-1 and sustains virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses during chronic infection. Nature immunology. 2011;12:663–671. doi: 10.1038/ni.2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shin H, Blackburn SD, Intlekofer AM, Kao C, Angelosanto JM, Reiner SL, Wherry EJ. A role for the transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 in CD8(+) T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity. 2009;31:309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Menner AJ, Rauch KS, Aichele P, Pircher H, Schachtrup C, Schachtrup K. Id3 Controls Cell Death of 2B4+ Virus-Specific CD8+ T Cells in Chronic Viral Infection. J Immunol. 2015;195:2103–2114. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crawford A, Angelosanto JM, Kao C, Doering TA, Odorizzi PM, Barnett BE, Wherry EJ. Molecular and transcriptional basis of CD4(+) T cell dysfunction during chronic infection. Immunity. 2014;40:289–302. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wirth TC, Xue HH, Rai D, Sabel JT, Bair T, Harty JT, Badovinac VP. Repetitive antigen stimulation induces stepwise transcriptome diversification but preserves a core signature of memory CD8(+) T cell differentiation. Immunity. 2010;33:128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]