Significance

Short-term plasticity (STP) of synaptic connections underlies many basic signal processing capabilities of the brain, such as gain control, temporal filtering, and adaptation. Glutamatergic synapses, the predominant excitatory synapses in the brain, display large variability both in basal synaptic strength and in STP. We show that a small fraction of release-ready vesicles are released with much higher probability than other vesicles. The number of these “superprimed” vesicles is variable among synapses, but increases strongly after application of phorbol ester, an analogue of the second messenger diacylglycerol, and after inducing posttetanic potentiation. Thus, modulatory transmitter systems, acting through the phospholipase-C–diacylglycerol pathway, will be able to upregulate superprimed vesicles and thereby boost synaptic strength at the onset of burst-like activity.

Keywords: posttetanic potentiation, short-term plasticity, calyx of Held, Munc13, phorbol ester

Abstract

Glutamatergic synapses show large variations in strength and short-term plasticity (STP). We show here that synapses displaying an increased strength either after posttetanic potentiation (PTP) or through activation of the phospholipase-C–diacylglycerol pathway share characteristic properties with intrinsically strong synapses, such as (i) pronounced short-term depression (STD) during high-frequency stimulation; (ii) a conversion of that STD into a sequence of facilitation followed by STD after a few conditioning stimuli at low frequency; (iii) an equalizing effect of such conditioning stimulation, which reduces differences among synapses and abolishes potentiation; and (iv) a requirement of long periods of rest for reconstitution of the original STP pattern. These phenomena are quantitatively described by assuming that a small fraction of “superprimed” synaptic vesicles are in a state of elevated release probability (p ∼ 0.5). This fraction is variable in size among synapses (typically about 30%), but increases after application of phorbol ester or during PTP. The majority of vesicles, released during repetitive stimulation, have low release probability (p ∼ 0.1), are relatively uniform in number across synapses, and are rapidly recruited. In contrast, superprimed vesicles need several seconds to be regenerated. They mediate enhanced synaptic strength at the onset of burst-like activity, the impact of which is subject to modulation by slow modulatory transmitter systems.

Glutamatergic synapses display a variety of dynamic changes in response to stimulation with action potential (AP) trains, ranging from immediate short-term depression to facilitation followed by depression (1). Both pharmacological (2–6) and molecular (7–9) perturbations have been described, which change such patterns from one to the other in a given synapse. Short-term plasticity (STP) has been shown to underlie many basic signal processing tasks of circuits in the central nervous system (10–13) and rapid changes of STP have been considered “... to be an almost necessary condition for the existence of (short-lived) activity states in the central nervous system” (ref. 14, p. 247). The balance between facilitation and depression is shifted during posttetanic potentiation (PTP) (15) and behavioral states are dynamically regulated by STP (16). Regulation occurs through slow, modulatory transmitter systems (17, 18). However, many open questions regarding the mechanisms underlying such changes remain. Modulation of presynaptic voltage-gated Ca2+ channels by slow transmitter systems is probably the most powerful mechanism of changing release probability (p) of synaptic vesicles (SVs) (19–21). Changes in intrinsic [Ca2+]i sensitivity of the release apparatus also contribute and have been investigated in the context of the phospholipase-C–diacylglycerol (PLC-DAG) signaling pathway (22–26) and posttetanic potentiation (15, 27–30), but the influence of this modulation on STP is less well understood.

Here, we describe heterogeneity of STP among synapses in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB)—the calyces of Held. AP-evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) vary in amplitude by more than a factor of 5 among calyx synapses and display divergent STP patterns (31). We show that such variability is similar to differences that can be experimentally induced by application of the DAG analog phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate (PdBu) and we explore the hypothesis that intrinsic heterogeneity of synaptic strength among synapses is caused by different degrees of activation of the PLC-DAG pathway, possibly due to the action of slow modulatory transmitter systems. We find that the very pronounced heterogeneity in p and synaptic strength among resting synapses rapidly vanishes during repetitive AP firing, such that EPSCs at steady state (EPSCss) become very similar, both during high-frequency stimulation and after conditioning with low-frequency trains. The remaining variability observed under such conditions shows very little correlation with the pronounced synapse to synapse variability of the initial EPSCs (EPSC1). Last but not least we find that EPSCs augmented by PTP share many features with those potentiated by PdBu application or by intrinsic modulation—in particular, a rapid loss of potentiation during repetitive stimulation.

We show that these findings can be quantitatively explained by a model, which assumes that resting synapses are endowed with a variable fraction of SVs, typically about 20–40%, that are in a “superprimed” state of elevated p (32). Application of PdBu or induction of PTP substantially increases the fraction of superprimed SVs and thereby the average p. During repetitive stimulation, responses of different synapses become more and more similar because superprimed SVs are consumed early, leaving normally primed SVs behind. Superpriming is a slow process, taking several seconds. It generates SVs with high p whereas normal priming is fast and supplies SVs with low p that maintain synaptic responses during sustained stimulation. Slow superpriming induced by activation of the PLC-DAG pathway has been observed before in the calyx of Held under voltage clamp, using step depolarizations (33). In hippocampal synapses, superpriming was shown to depend on the presence of at least one isoform of rab3 (32). We discuss our data in terms of a parallel SV pool model, in which normally primed and superprimed SVs reach their release-ready state independently. However, our data are equally compatible with a sequential process during which primed SVs mature to reach the superprimed state. We stress that the distinction between normally primed and superprimed SVs is not related to the previously described pools of slow and fast SVs at the calyx of Held (34). Rather, our data on AP-evoked EPSCs presented here demand that the latter needs to be subdivided, to accommodate normally primed and superprimed vesicles, respectively.

Results

Heterogeneity Among Release-Ready SVs.

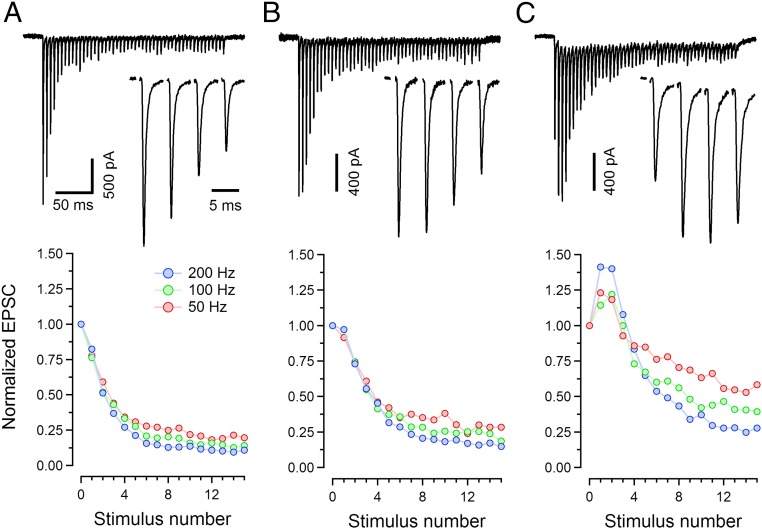

Calyces of Held represent a well-defined and homogenous population of axosomatic synapses that are thought to function as simple sign-inverting relays. For the majority of our experiments (Figs. 1–5) we stimulated afferent axons giving rise to calyx terminals and recorded AP-evoked EPSCs, using acute brainstem slices from P13–16 rats, as described previously (35). Some experiments were also performed using cultured hippocampal neurons (Fig. 6). When recording from voltage-clamped MNTB principal neurons and comparing EPSCs of different calyx synapses in response to trains of afferent fiber stimuli at frequencies ≥50 Hz, we can observe marked differences in their short-term plasticity. Fig. 1 gives three examples: One synapse shows pronounced depression at 50 Hz, 100 Hz, and 200 Hz (Fig. 1A); another synapse shows depression at 50 Hz, although with indications of some facilitation, superimposed onto depression for both 100 Hz and 200 Hz (Fig. 1B); and a third synapse shows pronounced net facilitation initially, followed by depression (Fig. 1C). In these examples the synapse with the strongest depression had the largest EPSC1. When responses recorded from 23 synapses under identical conditions are analyzed with respect to their EPSC1 and paired-pulse ratios (PPRs), a scatter plot of these two parameters shows a prominent correlation (Fig. 2, symbols with light colors). Such behavior has been described for other glutamatergic synapses before (36–38) and is generally interpreted in the sense that synapses with large EPSC1 have high p, which leads to substantial depletion of SVs already during the first few EPSCs.

Fig. 1.

Variability of short-term plasticity among calyx synapses. (A–C, Upper) Sample EPSC trains recorded in three different calyx synapses (P13–15) in response to high-frequency afferent fiber stimulation (200 Hz, 50 stimuli). Insets in A–C show the initial 4 EPSCs of the trains at a faster timescale. The bath solution contained 2 mM Ca2+ and 1 mM kynurenic acid for all experiments illustrated here and in Figs. 2–5. (A–C, Lower) Average EPSC amplitudes of the same synapses for three different frequencies (50 Hz, 100 Hz, and 200 Hz) were calculated from three to four repetitions and plotted against stimulus number. For clarity, only the initial 15 EPSC amplitudes are plotted.

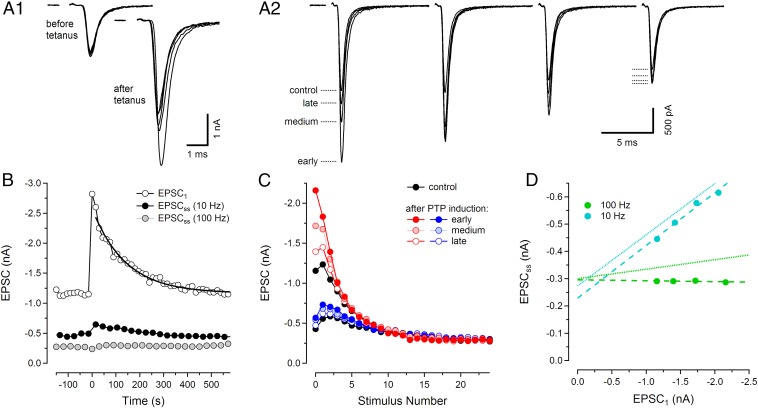

Fig. 5.

Posttetanic potentiation of EPSCs can be explained by enhanced superpriming of SVs. (A) EPSCs recorded before and at various time points after induction of PTP, which was induced by 8 s of tetanic stimulation (200 Hz). Before and after PTP induction, 100-Hz trains were delivered every 15 s, alternating with and without conditioning 10-Hz stimulation. (A1) Five individual EPSC1s recorded every 60 s before (Left) and every 15 s after (Right) delivering a 200-Hz tetanus. (A2) Superimposed EPSC trains at 100 Hz stimulation, recorded before and at three time intervals after PTP induction. For clarity, only the initial four EPSCs are shown. EPSC traces are averages of five (before), two (early), three (medium), and two (late) individual trains (exact timing in SI Text). (B) Average time course of PTP induction and decay obtained from seven synapses. EPSC1 amplitudes are plotted against start time of stimulus trains, relative to the time of PTP induction (open circles). An exponential was fitted to the decay time course of the EPSC1 amplitudes, starting with the second EPSC1 recorded after PTP induction (thick solid curve). In addition, EPSCsss are shown for 10 Hz (black circles, average of EPSC6 to EPSC10) and for 100 Hz (gray circles, average of EPSC21 to EPSC25). (C) Average EPSC amplitudes during 100-Hz stimulation are plotted against stimulus number, for trains both without (red curves and upper black curve) and with (blue curves and lower black curve) preceding conditioning stimulation (10 stimuli, 10 Hz). Averages were calculated for the same early, medium, and late time points as chosen in A2. (D) Average EPSCsss before and at early, medium, and late time points after PTP induction were calculated as in B and plotted against the corresponding EPSC1 for both 100 Hz (green circles) and 10 Hz (cyan circles). Superimposed on the data are both regression lines to the scatter plots (dashed lines) and, for comparison, the corresponding line fits from Fig. 3C (dotted lines).

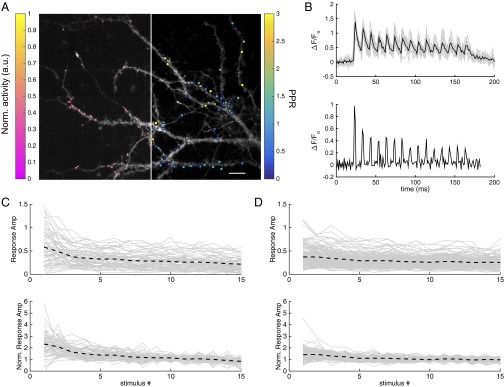

Fig. 6.

Imaging glutamate release from hippocampal boutons. (A) Dendrites of hippocampal neurons expressing iGluSnFR were imaged at 100 Hz during which 15 APs were elicited at 10 Hz. A, Left is overlaid with a color-coded map showing localization of release onto the dendrites. A, Right is overlaid with a map indicating the measured PPR for a given release site. (Scale bar, 10 µm.) (B) Individual normalized fluorescence traces from a single release site in response to the train stimuli are plotted in gray. The mean of 10 repetitions is plotted in black. Responses to individual stimuli overlap due to limited time resolution of the indicator. (B, Lower) Deconvolution of the mean fluorescence trace recovers the average response for a given stimulus. (C and D) Peak amplitudes of deconvolved average responses (shown in B) of all boutons from a representative recording without preconditioning (C) and with preconditioning (D) are plotted in gray. The black dashed line represents the mean of all boutons. In C and D, Lower, the response amplitudes are normalized to the mean of the last five responses in the trains.

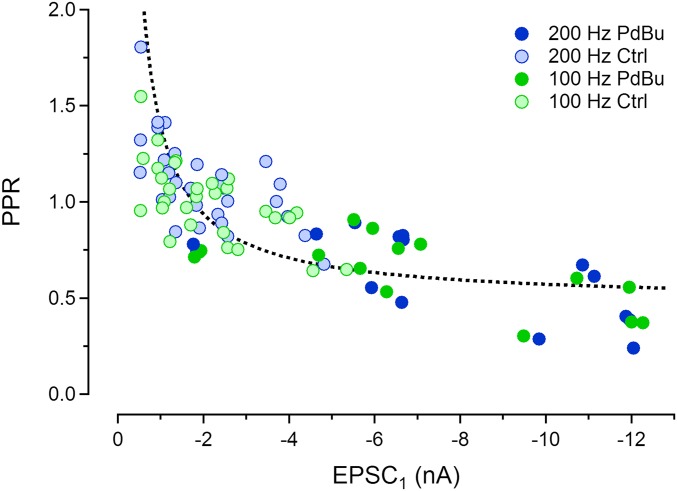

Fig. 2.

Paired-pulse ratios plotted as a function of EPSC1. EPSCs were measured in response to 100 Hz (green) and 200 Hz (blue) stimulus trains. Symbols with light colors represent EPSCs recorded under control conditions, and symbols with dark colors represent EPSCs recorded in the presence of 1µM PdBu. The dashed curve shows the prediction of a simple model as described in SI Text.

Differential Slow Modulation of p as a Likely Basis of Heterogeneity.

Some morphological variability seen among calyces of older mice (P16–19) has been reported to correlate with functional parameters (31). Here we explore possible mechanisms that generate functional heterogeneity among calyces. We considered that there may be constitutively active modulatory influences by slow transmitter systems (17, 18), which affect individual synapses differently. Many such influences operate through signaling pathways involving PLC and DAG. The DAG analog PdBu has been shown to increase EPSCs by a factor of 2–5 at the calyx (22, 23), mainly by increasing p. We therefore compared synaptic strength and STP in calyx synapses before and after application of PdBu. The set of 23 synapses analyzed in Fig. 2 includes seven cells, for which EPSCs were recorded both under control conditions (symbols with light colors) and after application of 1 µM PdBu (symbols with dark colors). Strikingly, EPSCs recorded in the presence of PdBu follow the same relationship between PPR and EPSC1 as seen under control conditions, extending the plot toward more than two times larger EPSC1. This finding suggests that similar processes may generate the heterogeneity of synaptic strength among individual calyx synapses and the potentiation of EPSCs by PdBu.

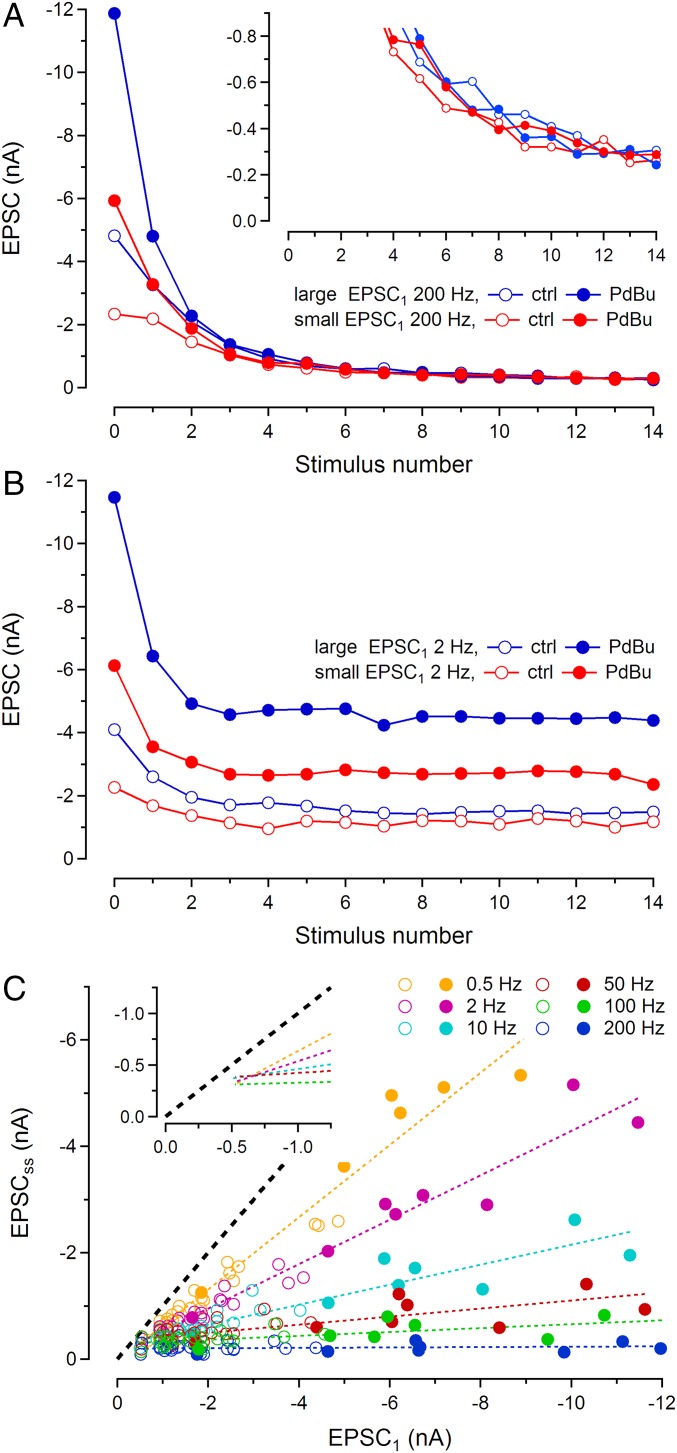

Another more surprising observation is that the heterogeneity, which is observed among rested synapses, quickly vanishes during repetitive high-frequency stimulation. Likewise, potentiation induced by application of PdBu quickly diminishes during EPSC trains. Fig. 3A compares two synapses (blue and red), selected to represent large differences in EPSC size. They were stimulated at a frequency of 200 Hz, both under control conditions (open symbols) and during application of 1 µM PdBu (solid symbols). Despite a more than fivefold difference in EPSC1, the amplitudes converge to a similar steady state (EPSCss) during repetitive high-frequency stimulation. This convergence does not approach zero, as seen in Fig. 3A, Inset, where the late sections of the EPSC trains are shown at expanded amplitude scale. Plotting EPSCss against EPSC1 for 200-Hz trains recorded in the larger sample of 23 synapses shows that there is little correlation between these two quantities (Fig. 3C, bottom trace, blue symbols). This plot includes both control (open symbols) and PdBu data (solid symbols) together with a fit to the combined datasets. If the sets are fitted separately, very similar regression lines with small slopes (0.014 ± 0.014 for control and 0.012 ± 0.01 for PdBu) are obtained. This result, again, points toward similar mechanisms underlying both endogenous heterogeneity and PdBu potentiation.

Fig. 3.

Dependence of EPSC amplitudes on stimulation frequency. (A) Variability disappears during high-frequency stimulation. Amplitudes of EPSCs during 200-Hz stimulus trains are plotted against stimulus number for two synapses. Blue symbols refer to a synapse with a large EPSC1 and red symbols to a weak synapse. Open symbols show amplitudes under control conditions and solid ones those after application of 1 µM PdBu. The curves converge toward similar steady-state values during stimulation. Convergence is not toward zero, but toward a common EPSCss of about −0.26 nA, as Inset shows at expanded y scale. (B) Superpriming is a slow process. Data from the same synapses as shown in A, but now obtained with 2-Hz stimulation, are plotted the same way. At such low frequencies, the heterogeneity among EPSC amplitudes is partially preserved at steady state. (C) Summary of data obtained from 23 synapses in a frequency range from 0.5 Hz to 200 Hz. EPSCsss (averages of the last 5 EPSCs) are plotted against EPSC1. Each symbol represents an individual synapse at a given frequency (color coded). Solid symbols are derived from experiments under PdBu, whereas open ones represent control conditions. The data for a given frequency are least-squares fitted by straight lines, the slopes of which change strongly with frequency. The line fits for lower frequencies (0.5–100 Hz) intersect at a common point (Inset reproduces the line fits without data points). The black dashed line is the identity line (slope = 1), which represents the case that EPSCss equals EPSC1 (no depression). Note that even the 0.5-Hz line fit has a slope lower than one.

At the calyx of Held, potentiation of neurotransmitter release by 1-oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG), a more physiological substitute for PdBu, has been interpreted as a slow maturation process of SVs, following their recruitment to the readily releasable pool (33). This process was found to display distinct pharmacology, involving PLC and DAG, and to take several seconds for completion. Likewise superpriming, described by Schlüter et al. in hippocampal neurons (32), was found to be slow to recover after high-frequency stimulation. We reasoned that the slowness of superpriming may be the cause for both the convergence of EPSC amplitudes of different synapses and the collapse of PdBu-induced potentiation during repetitive stimulation. Late in a high-frequency train, SVs are newly recruited and consumed in rapid succession. Thus, only a minority of released SVs will be superprimed, if superpriming is slower than normal priming. We therefore stimulated the same two synapses illustrated in Fig. 3A at 2 Hz to allow more time for superpriming in between stimuli (Fig. 3B). As expected, steady-state EPSCs at 2-Hz stimulation mirrored to a large extent the differences in EPSC1. Scatter plots of EPSCss vs. EPSC1 at lower frequencies (Fig. 3C) show distinct correlations between the two quantities, which are stronger, the lower the frequencies. In Fig. 3C, each symbol (color coded for frequency) represents one synapse at that frequency. Data points for a given frequency from different synapses are well approximated by straight dashed lines. In all cases, data obtained in the presence of PdBu (solid symbols) are perfectly consistent with those obtained under control conditions (open symbols), strengthening the notion that endogenous variations among resting synapses and potentiation induced by PdBu application are generated by the same mechanism.

The line fits for 100-Hz and lower stimulus frequencies converge at x and y values near −0.5 nA (Fig. 3C, Inset). Assuming that EPSCs reflect a sum of contributions from normally primed SVs (SVns) and superprimed SVs (SVss), this convergence finds an appealing interpretation: SVns uniformly contribute about −0.5 nA to EPSC1 in all synapses. An additional EPSC component that is variable in amplitude among different synapses is contributed by SVss. A formal treatment of such a “parallel pool model” is provided in SI Text. For such a model, synapses with increasing contributions of SVss to the EPSC move up along the line fit of the scatter plot. Given the mean EPSC1 of −1.78 nA and assuming the contribution of SVns to be about −0.5 nA, we conclude that SVss contribute an average of −1.28 nA. However, because of the approximately 5 times higher release probability, the number of release-ready SVss needs to be only 0.51 times that of SVns to contribute −1.28 nA to the EPSC. Thus, we may conclude that SVss account for approximately one-third of all primed vesicles. The slope of the (Δy/Δx) plot reports the ratio of EPSCss over EPSC1 for the SVs component. According to the model, the slope depends only on the SVs component and thus provides valuable information about superpriming. Ratios of EPSCss over EPSC1 are commonly used to quantify short-term depression (STD), although they may be influenced by facilitation (increase in p) and by desensitization. We therefore refer to the slope for a given frequency as depression (STD) of the SVs component, keeping in mind that this may represent a simplification.

Our finding that such data for several frequencies and across many cells, both for control and in the presence of PdBu, can well be approximated by straight converging lines can be taken as evidence that (i) synaptic responses have a SVn component, which is similar among individual synapses and displays little STD for stimulus frequencies of 0.5–50 Hz; (ii) there is an additional, variable component contributed by SVss displaying strong STD even at low frequencies; and (iii) PdBu predominantly modulates the variable SVs component. A simple two-pool model corroborates these conclusions in a quantitative way (SI Text).

Time Course of Consumption of the SVs Component and Its Frequency Dependence.

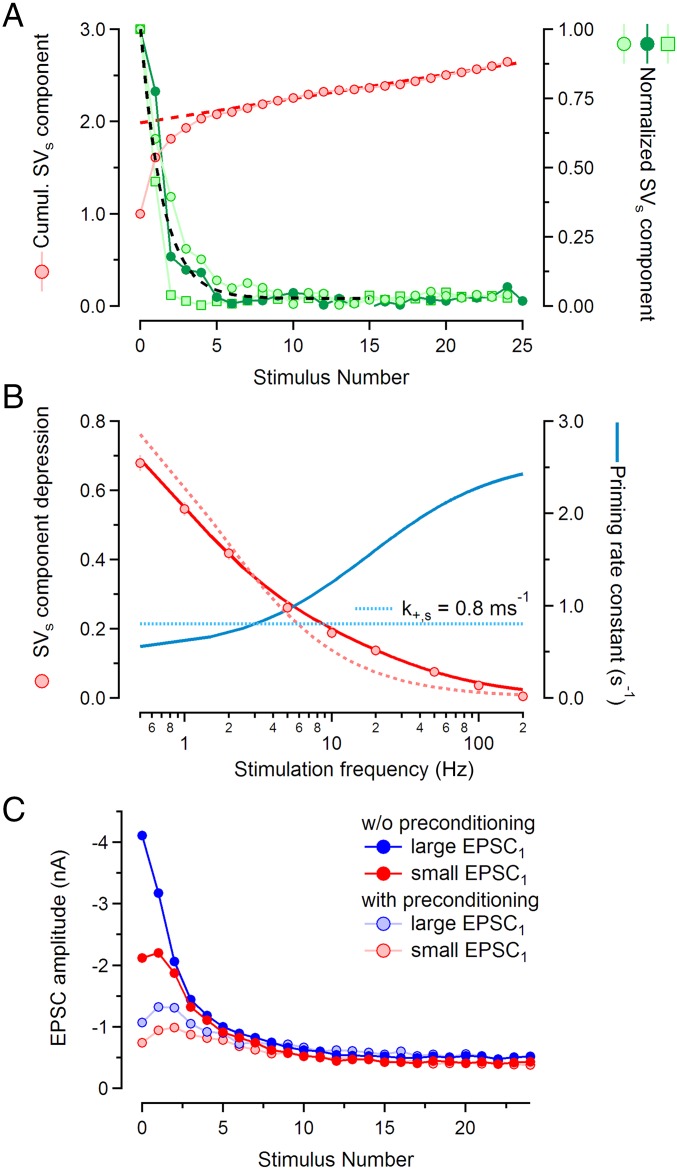

Assuming that SVs and SVn contributions to EPSCs are additive and that the latter is relatively uniform among individual synapses, it is straightforward to determine the time course of the SVs contribution during stimulus trains by forming differences between EPSC amplitudes obtained in synapses with either high or low contributions of SVs to the EPSCs (32). We refined this approach by allowing for the fact that SVn components may not be exactly the same for high-SVs and low-SVs synapses due to cell-to-cell variations. Thus, we did not subtract the entire low-SVs response from the high-SVs response, but a fraction of it. The criterion for selecting the fraction (usually very close to 1) was that the resulting EPSC component contributed by SVss has a depression ratio, determined by the slope in Fig. 3C, which is 0.036 ± 0.008 for 100-Hz stimulation. Fig. 4A shows three examples of such amplitude time courses, normalized to an initial value of 1 (green traces, right ordinate) and an exponential fit to their average (black dashed curve). These traces are normalized because the absolute amplitudes unfortunately do not provide information about the sizes of the SVs pools of individual synapses, but report only differences (details in Fig. 4 legend). Nevertheless, we can calculate the release probability of SVs (ps) because it is the ratio of EPSC1 over pool size, for which absolute pool sizes cancel out. To do so, we calculated normalized SVs pool size by back extrapolation of a linear fit to the cumulative version of the normalized average time course of Fig. 4A (red traces), as described previously (39, 40). The SVs pool size was found to be 1.99 ± 0.02 (in units of EPSC1). Thus, EPSC1 consumes a fraction of 1/1.99 of the SV pool, corresponding to ps = 0.497 ± 0.005 (note that here and in the following text subscripts, s and n are used for denoting parameters for superprimed and normally primed vesicles, respectively).

Fig. 4.

Isolating the superprimed component of EPSCs. (A) Normalized time courses of contributions from superprimed SVs during 100-Hz trains are plotted against stimulus number (right ordinate). Three examples are shown, each of which was calculated as a difference between average 100-Hz train responses from a set of synapses with large EPSC1 minus the corresponding average from synapses with small EPSC1 multiplied by a weighting factor (0.87, 0.822, and 1.06 for the three traces). The lowest trace displays a very rapid decay toward zero, followed by some rebound. This may indicate some residual AMPAR desensitization that is relieved when quantal content is reduced toward steady state. The black dashed curve represents a least-squares fit of an exponential plus baseline to the average of the traces. Superimposed is the cumulative version of the average trace (red circles, left ordinate), together with a line fit to the amplitudes of EPSC11 to EPSC25. (B) Frequency dependence of the steady-state occupancy of the SVs pool. Slopes of line fits from Fig. 3C are plotted against the logarithm of the stimulus frequency (red symbols) together with an adequate fit (solid red curve) and a fit for a fixed priming rate constant of 0.8 s−1 (dotted light red curve). Superimposed are the rate constants used for the fits (blue curve, right ordinate). These were either fixed at 0.8 s−1 or else calculated with a Michaelis–Menten-type function (basal value 0.5 s−1, maximum value 2.4 s−1, K0.5 at 15 Hz). This combination of parameters was used together with ps = 0.5 (SI Text). (C) Conditioning stimulation converts depressing EPSC trains into facilitating ones. EPSC amplitudes during 100-Hz stimulus trains are plotted against stimulus number, for trains both without (symbols with dark colors) and with (symbols with light colors) preceding conditioning stimulation (10 stimuli, 10 Hz). Averages from two groups of synapses (three each) are shown, one with large EPSC1 (mean = −4.11 nA, blue symbols) and one with smaller EPSC1 (mean = −2.12 nA, red symbols). Conditioning stimulation reduces differences in synaptic strength among synapses (ratio between EPSC1 values was 1.94 and 1.45 for 100-Hz trains without and with conditioning 10-Hz stimulation, respectively). It turns STD into facilitation, revealing properties of the contribution of SVns.

Another ps estimate can be obtained from the time constant of an exponential fit to the average decay time course of the component contributed by SVss to each EPSC during trains (Fig. 4A). For a simple depletion model (SI Text) the time constant τs of approach to steady state is determined by both ps and the priming rate constant. Its inverse is just the sum of both quantities, if τs and priming rate constant are measured in units of the interstimulus interval (ISI). For a SV pool, which depletes almost completely—such as the SVs pool during 100-Hz stimulation—the priming is slow, relative to SV consumption, and therefore ps is close to 1/τs. The exponential fit to the average time course shown in Fig. 4A has a decay τs = 1.43 ± 0.08 ISIs, corresponding to ps = 0.70 ± 0.04. This value is significantly larger than the ps estimated from EPSC1 and SVs pool size above (0.497 ± 0.005). This difference is most likely due to facilitation building up during the stimulus train, because the exponential fit describes the approach to steady state toward the end of the EPSC trains, whereas the first estimate was largely based on EPSC1. Taking the ratio of the two ps estimates, we may conclude that facilitation, expressed as an increase in ps, enhances release by a factor of 1.41.

In Fig. 4B we explore the frequency dependence of the steady state of the SVs component. Slopes of line fits of Fig. 3C are plotted against the logarithm of stimulus frequency. We discuss these slopes, which are ratios of steady-state over initial amplitudes of the isolated SVs components, in terms of the abovementioned parallel pool model. The model assumes that a given pool of SVs is consumed at a rate constant proportional to p and stimulus frequency. This pool is refilled with rate constant k+. The size of it is assumed to be variable among synapses and modulated by PdBu or by induction of PTP. In addition to the SVs pool, there is a fixed-size SVn pool, the properties of which are further discussed below (SI Text). Disregarding possible effects of facilitation and desensitization, such a model predicts that STD of the SVs component (reported by the slope of the line fits in Fig. 3C for a given stimulus frequency) is given by 1/(1 + f/fs), where the characteristic frequency fs is the ratio of the priming rate constant k+,s (in units of 1/ISI) and the release probability ps of the SVs pool. When trying to fit measured slopes (Fig. 4B) with this relationship and assuming both k+,s and ps to be constant, the results are not compatible with the data (light red dotted curve in Fig. 4B, which we consider the best fit under this constraint). Using a Michaelis–Menten-type function for a frequency-dependent k+,s and constant ps = 0.5, however, provides a good fit (Fig. 4B, solid red line). Fig. 4B also includes k+,s values, both for the case of a frequency-dependent modulation of the priming rate (solid blue trace) and, for comparison, the constant priming rate of 0.8 s−1 (dotted blue horizontal line). The frequency dependence of k+,s, which spans almost a factor of 5 in the frequency range of 0.5–200 Hz, most likely reflects a [Ca2+]i dependence of the superpriming process. Our values for k+,s are very similar to those found for the recovery of the rate of release after pool-depleting stimuli in voltage-clamped calyx of Held terminals (ref. 33, their figure 2C). Together the data show that for stimulus frequencies >20 Hz the contribution of SVss to EPSCss is <10% under our recording conditions due to a combination of slow priming and high p. It should be noted that the pool filling state would be predicted to be even lower than 10%, if ps were assumed to increase due to facilitation. Below, we show that the priming rate of SVns is about six times faster than that of SVss, whereas their p is at least three times lower.

Conditioning Stimulation Reveals Properties of Normally Primed SVs.

Considering that under control conditions (absence of PdBu) most of the SVs component is strongly depressed during ongoing stimulation, the majority of release at steady state must be contributed by SVns. Based on the data of Fig. 4B, we expect that even at frequencies as low as 10 Hz the SVs pool is depleted by more than 80%. This finding opens the possibility to study the properties of SVns in isolation with little contamination from SVss. For instance, if a 100-Hz stimulus train is applied after 10-Hz conditioning stimulation, we expect to observe during the 100-Hz episode mainly the STP dynamics of SVns. This result is illustrated in Fig. 4C, where EPSC train amplitudes during the 100-Hz phase are plotted against stimulus number, both for nonconditioned (symbols with dark colors) and for conditioned trains (symbols with light colors). Average EPSC amplitudes from two groups of synapses (n = 3 each) are compared. The first group consists of synapses with relatively large EPSC1 (blue symbols), whereas for the other group synapses with smaller EPSC1 were selected (red symbols). The comparison shows that conditioning evens out differences among synapses and turns short-term depression into initial facilitation followed by depression. A similar analysis performed on EPSCs recorded in the presence of PdBu showed that 10-Hz conditioning has a similar effect on PdBu-potentiated synapses (n = 4), rendering initial amplitudes more similar and increasing PPR from a control mean value of 0.67 to 1.23.

A conversion of STD into pronounced facilitation by conditioning stimulation was shown previously (41) and interpreted as a reduction in release probability. In the light of the present study, the reduced release probability is seen as a selective depletion of SVss. However, even after 10-Hz conditioning, the EPSC trains shown in Fig. 4C may still contain a small SVs component, which is reduced to approximately one-fifth at steady state for this frequency. Nevertheless, except for the first few EPSCs, any contribution of SVss during 100-Hz stimulation must be minor, because the SVs component is reduced to 4% at that frequency. At steady state, the total consumption of SVs is balanced nearly exclusively by recruitment of new SVns. We therefore can conclude that SVns are primed at a rate of ∼50 SVs per ISI or 5,000/s (assuming an EPSC amplitude of −0.5 nA contributed by SVns and a quantal size of −10 pA in the presence of 1 mM kynurenic acid). Compared with that, a synapse with −2 nA of SVs contribution to EPSC1, depressing to about 4%, superprimes only 8 SVs per ISI. In this sense, one can conclude that superpriming is about sixfold slower than normal priming at 100-Hz stimulation. However, pn, the p of SVns, is substantially lower than that of SVss, as the following consideration shows.

As detailed above, the inverse time constant for the approach of EPSC amplitudes to steady state is the sum of the priming rate constant k+ (in units of ISIs) and p. Unlike the priming rate constant of SVss, that of the SVn pool is large and not negligible, such that pn < 1/τn. Fitting exponentials to the late phases of several sets of 100-Hz EPSC trains conditioned by 10 Hz stimulation, such as those illustrated in Fig. 4C, we obtained an average value for τn of 5.4 ISIs. Thus, we can conclude that pn at steady state is <0.18. This value is considerably lower than the estimated ps of 0.7, as obtained above with the same method. Similar to the estimated ps, the value of 0.18 may represent a facilitated synapse, such that the initial pn may well be in the range of 0.1–0.15. In the case that the pool of SVns is depleted to only 50%, the initial pn may be further decreased by one-half. Unfortunately, more accurate values for pn and k+,n are hard to obtain due to the uncertain residual filling state of the SVn pool. The important finding, however, remains that at rest pn << ps. During high-frequency stimulation SVss are rapidly depleted, such that release is supported mainly by SVns. Due to facilitation, however, p of these remaining SVns will increase as stimulation continues and pn may increase to about 40% of ps’s initial value. For this reason, it is hard to distinguish the two components kinetically, unless a detailed analysis is performed. Furthermore, our results suggest that the superpriming rate is [Ca2+]I dependent and quite low at low stimulation frequencies (Fig. 4B, blue solid line). Due to rapid decay of residual [Ca2+]i after stimulation, [Ca2+]i is near baseline during most of the SVs pool recovery period. Given the basal superpriming rate constant of 0.5 s−1 (see above), the time constant of recovery will therefore be in the seconds range. In contrast, priming of SVns is fast, at least during high-frequency stimulation. Even if it were slower at rest, substantial refilling of the SVn pool might occur while [Ca2+]i is still elevated after stimulus trains.

Discharge rates in the rodent peripheral auditory pathway are quite high in vivo, even in the absence of acoustic stimulation [median = 10–20 Hz (42)]. Given the low rate of superpriming, this may imply that the pool of SVss is mostly in a depleted state under physiological conditions. However, two considerations will qualify such a conclusion: (i) Our estimate of eight SVss being primed per 10 ms (100 Hz) relates to room temperature. Given a strong temperature dependence of the priming process (43), this rate may double at physiological temperatures. (ii) The estimate represents control conditions. Assuming that endogenous modulators have an effect similar to that of PdBu application, the contribution of SVss may be tripled. In combination, these two effects may lead to a superpriming rate of 48 SVss per 10 ms or 120 vesicles per ISI at 25 Hz. Thus, effective modulation of synaptic strength and short-term plasticity by SV superpriming may very well occur also under physiological conditions.

Posttetanic Potentiation Shares Properties with PdBu Potentiation and Intrinsic Variability.

Posttetanic potentiation is a form of medium-term plasticity (44), during which p (27, 45) and, to a lesser extent, also pool size (15, 46) are increased. It is induced by seconds-long high-frequency stimulation after which synaptic strength is transiently elevated and decays back to control values over several minutes. We hypothesized that PTP may be mediated through a transient increase of the SVs pool and asked whether PTP shares properties with PdBu potentiation, as well as with the intrinsic heterogeneity of synaptic strength as described above. To test this hypothesis, we recorded 100-Hz EPSC trains every 15 s in P15–16 synapses, alternatingly with and without preceding conditioning episodes (consisting of 10 APs at 10 Hz). We then induced PTP by applying 8 s of 200-Hz stimulation before resuming 100-Hz stimulation every 15 s, again with and without preceding 10-Hz conditioning. We found that EPSC1 amplitudes were potentiated to various degrees. The EPSC1 of the very first train after PTP induction (7 s after the end of the tetanus) was exceptionally large in some cases and exhibited a slightly increased synaptic delay (Fig. 5A1; also ref. 15). Therefore, we excluded this first train from further analysis. Subsequently, EPSC1 amplitudes decayed exponentially back to control values. We analyzed nine synapses, in which we were able to complete a total of 19 cycles of PTP induction and recovery. For this dataset, EPSC1 was potentiated by 115 ± 10%, measured by means of an exponential fit to the EPSC1 values and back extrapolation of this fit to the end of the PTP-inducing stimulus train.

To analyze other features of PTP, we concentrated on those synapses that showed relatively strong PTP (≥90%). These were seven synapses, with 13 cycles of PTP induction and recovery. The average time course of PTP induction and decay is shown in Fig. 5B. PTP is induced at time 0, causing more than doubling of EPSC1 (average increase = 134 ± 10%, estimated by the procedure described above). After PTP induction, EPSC1 amplitudes decayed back to control values with a time constant of 155 ± 16 s. For comparison, Fig. 5B also illustrates PTP-induced changes in EPSCss, for both 100-Hz and 10-Hz stimulation. Contrary to EPSC1, late EPSCs during 100-Hz trains were hardly changed by PTP induction. This finding is consistent with the assumption that PTP primarily increases the contribution of SVss to the EPSC, which are nearly depleted at steady state during 100-Hz trains. The 10-Hz EPSCss shows only slight potentiation, similar to what was observed for PdBu-induced potentiation of EPSCss at this frequency and compatible with the slope of the 10-Hz regression line in Fig. 3C.

To visualize changes in short-term plasticity within EPSC trains recorded in potentiated synapses, we calculated average EPSC amplitudes for 100-Hz trains at four time points along the cycles of control—PTP–induction–recovery. The traces are denoted as control (before induction of PTP, black), early (2nd and 3rd train after PTP induction, disregarding the very first EPSC1), medium (4–6th train), and late (8–10th train) (Fig. 5C). Results from train stimulation both with (Fig. 5C, blue symbols) and without (Fig. 5C, red symbols) preceding 10-Hz conditioning stimulation are shown. In agreement with ref. 15 we found that differences between the EPSC trains measured before and those measured at various time points after PTP induction vanish after three to five stimuli. These findings are consistent with a rapid depletion of SVss and are similar to those shown in Fig. 3A, where the differences between 200-Hz EPSC trains either were induced by PdBu application or else reflect intrinsic heterogeneity among synapses. Likewise for EPSC trains following conditioning stimulation (Fig. 5C, blue curves) the differences between control and PTP potentiated cases are very much reduced. Also, a sequence of facilitation followed by STD is observed throughout, In contrast, 100-Hz EPSC trains without conditioning stimulation display pronounced STD, when recorded early after PTP induction.

In Fig. 5D we plot EPSCss vs. EPSC1 in analogy to Fig. 3C. Here EPSCss values for the different time points before and after PTP induction (control, early, medium, and late) are plotted against the respective EPSC1 both for 100-Hz trains (green symbols) and for 10-Hz trains (cyan symbols). Despite the narrow dynamic range of PTP-induced EPSC amplitude changes, the data points show a clear trend and converge at low values. They intersect at −0.353 nA (dashed lines), similar to the case of Fig. 3C. For comparison, the linear fits for the 10-Hz and 100-Hz data points of Fig. 3C are included (Fig. 5D, dotted lines). This comparison shows that amplitude changes observed during various degrees of PTP are well compatible with the idea that they represent various degrees of superpriming. The finding that PTP is almost absent from EPSCss even for a stimulus frequency as low as 10 Hz is readily explained by the slow refilling of the SVs pool (Fig. 4B).

Together our data indicate that four dynamic features of EPSCs evoked by train stimulation, such as (i) pronounced STD during high-frequency stimulation, (ii) a conversion of that STD into a sequence of facilitation followed by STD after a few conditioning stimuli at low frequency, (iii) an equalizing effect of such conditioning stimulation, which reduces differences among synapses and reduces potentiation, and (iv) a requirement of long periods of rest for reconstitution of the original STP pattern, are shared by PdBu potentiation and PTP. Together with the finding that PTP is partially occluded in synapses with large EPSC1 (27), our results strongly suggest that both PTP and PdBu potentiation have a common basis.

Heterogeneity Among Individual Active Zones?

Heterogeneity with features very similar to those described here was observed among individual boutons in cultured hippocampal neurons by Waters and Smith (47). Using styryl dyes, these authors reported remarkable heterogeneity in the rate of FM1-43 destaining, when measured during 1-Hz stimulation. When stimulating at 10 Hz, however, much less heterogeneity was observed, except for the initial 10–30 responses. These findings recapitulate our results shown in Fig. 3, albeit at lower stimulus frequencies. Waters and Smith suggested that heterogeneity arises from differential partitioning of SVs between the readily releasable pool (RRP) (measured by sucrose stimulation) and the recycling pool (measured by styryl dyes). We hypothesized that a subdivision of the RRP into primed and superprimed components might offer an alternative explanation for their observations. To test this hypothesis, we expressed the novel glutamate sensor iGluSnFR (48) in cultured hippocampal neurons and applied a 10-Hz field stimulation either with or without 1-Hz preconditioning. This method allowed us to measure simultaneously the release of Glu in response to individual stimuli at up to 186 boutons in a given imaging frame (Fig. 6 A and B). In five experiments, in which the signal-to-noise ratio was large enough to allow quantification of the steady-state response size during 10-Hz stimulation, we observed pronounced heterogeneity among presynaptic boutons [coefficient of variation (CV) = 0.61 ± 0.10, n = 5], when analyzing ratios of the initial responses relative to steady state (Fig. 6C). This heterogeneity diminished for responses measured later during the stimulus trains. In contrast to what we observed during train stimulation of calyx synapses, there was substantial heterogeneity also in the size of steady-state responses (note that traces in Fig. 6C, Lower are normalized with respect to the average of the last five responses). This result probably reflects the well-known size differences of hippocampal boutons and the “scaling” of EPSCs with respect to SV numbers (37). Such differences may be averaged out over the several hundreds of active zones of a given calyx terminal.

In agreement with our findings at calyx synapses, the heterogeneity among boutons of cultured hippocampal neurons regarding their initial responses during stimulation with high-frequency trains is reduced after conditioning with low-frequency trains (CV = 0.37 ± 0.05, n = 4, Fig. 6D, compared with 0.61 ± 0.10, see above), indicating that even at frequencies as low as 1 Hz the putative pool of SVss is partially depleted. These results are consistent with the assumption that heterogeneity among boutons is due to a variably sized SV pool that depletes quickly during the first three stimuli of high-frequency trains or during longer-lasting low-frequency stimulation. This pool cannot represent the entire RRP, because depletion of the latter requires several tens of stimuli. Rather, we propose that—as in the calyx—it consists of a small number of SVss, which represent only a subset of the entire RRP.

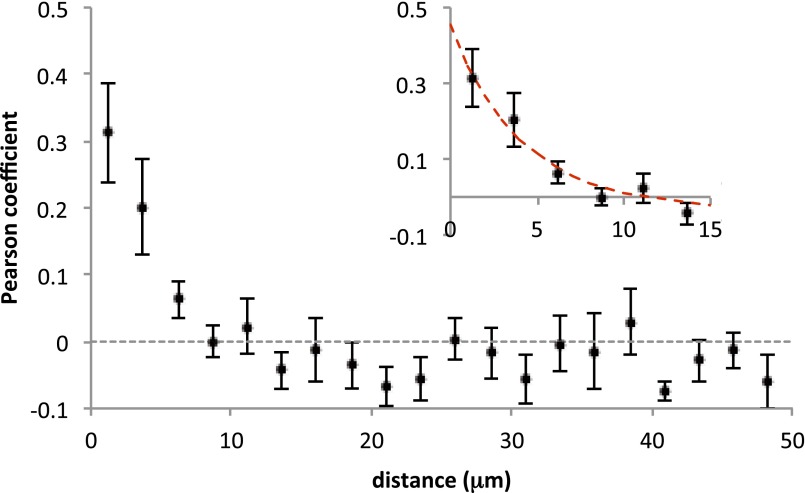

The heterogeneity among individual synaptic boutons is probably averaged out in whole-cell EPSC recordings in hippocampal neurons. Why is heterogeneity nevertheless observed in whole-cell EPSC recordings in MNTB principal neurons? Here, another finding might offer an explanation. As previously reported (38), we observed that p estimates are correlated for neighboring hippocampal boutons. Fig. 6A, Left shows PPRs as color-coded dots, superimposed onto individual synaptic contacts. A clustering of bright spots (high PPR–low p) in certain regions of the dendritic tree is quite obvious. In Fig. S1 we plot the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) of PPRs against distance ri,j. To do so, we averaged PCC over all pairs of boutons, which were located within bins of 2.5-µm widths. A pronounced correlation extends over about 10 µm with a length constant of 4.1 µm (Fig. S1). These dimensions are comparable with the total extent of a calyx terminal. Therefore, it is well possible that the signal determining the degree of SV superpriming is similar for all active zones in a given calyx terminal, but differs among calyces, whereas it is averaged out in a widely branched dendritic tree of a cultured hippocampal neuron.

Fig. S1.

Spatial correlation of PPR between neighboring boutons. Release site pairs were grouped into 2.5-µm bins and cross-correlation of corresponding PPR values was performed. The mean ± SEM of correlation coefficients recovered from all measurements (n = 9) is plotted for pairs up to 50 µm apart. The decay of correlation with increasing distance was fitted with a single exponential (Inset) and a PPR correlation length constant of 4.1 µm (95% confidence interval: 2.6, 5.7) was determined. Error bars indicate SD.

Discussion

Several recent studies described perturbations, either pharmacological or genetic, which change the synaptic release probability in the absence of changes in Ca2+ current, [Ca2+]i dynamics, and SV pool sizes (8, 49–51). Whereas changes in the latter parameters are well understood and have been recognized as strong modulators of transmitter release, the mechanisms underlying differences in “intrinsic” release readiness have received less attention. Here, we study three forms of variation in synaptic strength: intrinsic synapse-to-synapse variability; potentiation by the DAG analog PdBu; and PTP, a form of medium-term synaptic plasticity. We show that these three forms of variation display remarkably similar properties, which can be readily and quantitatively explained by the existence of a relatively small subpool of superprimed SVs (SVss, ∼30%) with high p (∼0.5) that is slowly regenerated upon depletion. Following this notion, differences in the size of this pool generate intrinsic heterogeneity among synapses with respect to the mean p, whereas both PdBu and PTP increase the proportion of SVss and thereby regulate synaptic strength and plasticity. In contrast, the pool of normally primed SVs (SVns) is quite similar in size for individual synapses and remains largely unchanged after PdBu application or PTP induction. SVns have low p and are rapidly regenerated after vesicle fusion. We show that high-frequency activity strongly enhances superpriming, most likely via elevated [Ca2+]i. However, even during 100-Hz trains superpriming is much slower than normal priming. This property, combined with high p of about 0.5, leads to the characteristic kinetic STP features described here, which include rapid depletion of the SVs pool, during both high-frequency stimulation and low-frequency conditioning, leaving behind SVns. The latter have low p, which, however, may increase during high-frequency stimulation due to facilitation. Importantly, the majority of SVs consumed during medium- and high-frequency activity are supplied by the SVns pool, due to its high priming rate. In contrast, the contribution of SVss is dominant only at very low spike rates and at the onset of burst-like activity.

Molecular Mechanisms Regulating Superpriming of SVs.

So far, we have interpreted our results in terms of a parallel model that comprises two pools of SVs that are consumed independently with different p and are replenished at different rates. One of the pools is modulated in its size and rate of priming, whereas the other one is static. Alternatively one may assume that SVs undergo a sequential process of initial priming to a state of low p, followed by a slow step of maturation to a state of higher p, as suggested in ref. 52 for cerebellar mossy fiber terminals. If the two states are in a dynamic equilibrium with each other, heterogeneity will arise by different proportions of SVs residing in the superprimed state at rest. This view further suggests that PdBu and PTP shift the population of vesicles toward the state of high p. Such a sequential kinetic scheme is hard to distinguish experimentally from a parallel one, if the first step in the sequence is fast compared with the second one, as is the case at the calyx synapse. However, irrespective of whether superpriming converts normally primed SVs into superprimed ones or else acts on unprimed SVs directly, it is interesting to explore molecular mechanisms under the assumed constraint that PTP, PdBu-induced potentiation, and Rab3 superpriming (32) are mediated by the same or by similar processes. Basu et al. (26) found that interfering with the C1 domain of Munc13 (a target for DAG action) abolished all PdBu-mediated effects and shifted the synapse into a high p state, similar to a PdBu-potentiated synapse. The authors discussed this effect in terms of two conformational states of Munc13, regulated by binding of PdBu (or DAG) to its C1 domain—one state resulting in high p and the other one in low p. Given the fact that Munc13 is a protein with several regulatory domains responsive to DAG, [Ca2+]I, and calmodulin/Ca2+ (53), this protein appears as a central hub for modulatory influences on p and superpriming. This view is corroborated by early work on superpriming (32), which implicates the Munc13–Rim–Rab3 interaction as another requirement for this SV maturation process. On the other hand, recent evidence assigns decisive roles to specific isoforms of PKC (6, 28) and PKC-mediated phosphorylation of Munc18 (29) to the induction of PTP. However, assuming that PTP and PdBu-induced potentiation act through the same mechanism (evidence provided here) and given the finding that all effects of PdBu are eliminated by disrupting its interaction with Munc13 (26), we may conclude that Munc13 executes both forms of potentiation by regulating the energy barrier for SV fusion (54). PKC, on the other hand, may enable such regulation through targets, which are part of the release machinery. An example for such enabling reactions is the phosphorylation of Munc18 by PKC (24).

Previous studies at the calyx of Held separated the entire SV population releasable by long-lasting step depolarizations under voltage clamp into two kinetically distinct pools: (i) a slowly releasable pool (SRP) of about 1,500 vesicles, which can be released by such strong stimulation only (34, 55) and contributes little to AP-evoked EPSCs, and (ii) a fast releasable pool (FRP) of similar magnitude, which contributes the vast majority of SVs released during APs. Evidence provided here suggests that SVs of the FRP need to be further subdivided into normally primed and superprimed ones. The SRP likely represents SVs, which have a perfectly assembled release apparatus, but are localized somewhat less favorably with respect to Ca2+ channel clusters than FRP vesicles (ref. 56; but see ref. 57). This, together with the considerations above regarding the molecules involved, suggests an attractive scenario for the case that a sequential reaction scheme applies (51): Release-competent SRP vesicles with a fully functional release apparatus undergo a process of positional priming, which moves them closer to Ca2+ channels by interaction with the active zone through Rim, Rab3, and Rim binding protein (58, 59), turning them into FRP vesicles. This process depends on an intact cytoskeleton (33) and happens on the 100-ms timescale. It results in primed SVs with an initial p of 0.1–0.2. Their fast generation and low release probability characterizes them as SVns. Once interacting with the active zone, the conformational state of Munc13 may slowly shift, which converts SVns into SVss with a p of ∼0.5. The partitioning between primed and superprimed SVs is controlled by DAG and [Ca2+]i and by interactions of Munc13 with the abovementioned active zone proteins, possibly including GIT (49). In the scenario of a parallel model, these interactions would provide a dynamically changing number of sites for superpriming. Augmentation, a form of synaptic plasticity temporally in between STP and PTP (44, 60), might be represented by the Ca2+-dependent superpriming rate (changing the size of the SVs pool in synchrony with global [Ca2+]i). PTP, on the other hand, would be brought about by a change in the set point of the SVn–SVs partitioning or else by the establishment and disappearance of SVs sites under the influence of more slowly changing second messengers and by phosphorylation reactions.

Superpriming May Be a Widely Spread Phenomenon Among Excitatory Synapses.

The characteristic features of superpriming, as described here, have been observed at glutamatergic synapses in a variety of contexts. Heterogeneity among individual hippocampal synapses has been described both for slice preparations (37, 61) and for cultured hippocampal neurons (38, 62). Hanse and Gustafsson analyzed this heterogeneity at single release sites in the CA1 area of the hippocampus (63, 64). Their findings are reminiscent of the features reported here for calyx synapses. These features include large variability and rapid depletion of a small “preprimed pool” during stimulation, lack of correlation of first response amplitudes with the average release during trains, and accelerated priming during trains. Using styryl dyes and cultured hippocampal neurons, strong heterogeneity of release was observed among individual boutons, when stimulating at 1 Hz, whereas synaptic strength was more uniform, with some of the remaining heterogeneity disappearing after a few stimuli, when stimulating at 10 Hz (47). Ishiyama et al. (65) describe a decrease in p in granule cell to basket cell synapses of the cerebellum of Munc13-3−/− mice. They interpret their observations as a loss of a superpriming action of Munc13-3. A small number of release sites with especially high release probability were postulated to mediate release during low-frequency stimulation at the neuromuscular junction (66). Taken together, these results suggest that superpriming is a widely spread mechanism among excitatory synapses. It provides enhanced synaptic strength for a few initial APs during a burst of activity. This enhancement happens only when AP bursts have been preceded by periods of quiescence of a few hundred milliseconds. Its impact on network properties can be modulated by slow neurotransmitter systems.

Materials and Methods

Slice Preparation and Electrophysiology.

Juvenile, posthearing (P13–16) Wistar rats of either sex were used. All experiments complied with the German Protection of Animals Act and with the guidelines for the welfare of experimental animals issued by the European Communities Council Directive. Brainstem slices were prepared as previously described (35). Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made from principal neurons of the MNTB, using an EPC-10 amplifier controlled by “Pulse” software (HEKA Elektronik). Action potentials were elicited by afferent fiber stimulation. All experiments were carried out at room temperature in the presence of 1 mM kynurenic acid to minimize AMPAR saturation and desensitization (SI Materials and Methods).

Statistical Analysis and Model Calculations.

Offline analysis was performed using “Igor Pro” (Wavemetrics). Original data are presented as mean ± SEM. SDs of parameters are given as provided by Igor Pro curve-fitting programs. For derived quantities (products, ratios, etc.) SEM was calculated assuming Gaussian error propagation.

Optical Measurements.

Primary hippocampal neuron cultures were prepared from 1-d-old Wistar rats according to the regulations of the Max Planck Society. Calcium phosphate-mediated transfection of neurons with iGLuSnFR (Addgene plasmid 41732) was performed at 3 d in vitro (DIV) and experiments were performed at DIV 14–21. Images were acquired at 100 Hz with a Zyla 5.5 sCMOS camera (Andor Technology). Action potentials were elicited by field stimulation. All experiments were performed at room temperature (SI Materials and Methods).

SI Text

The Parallel Two-Pool Model.

For a simple quantitative description of our results we assume that resting synapses have a pool of SVns, which is similar in size among synapses. SVns are released during an AP with release probability pn. The SVn pool, when fully loaded, has the size Nn. In addition, individual synapses have a pool of SVss of variable size, which has a size α × Nn. Here, α is a constant for a given synapse, representing the abundance of sites for SVss. α increases in response to PdBu application or during induction of PTP. SVss are released with higher release probability, which is β × pn. Thus, the total quantal content m1 of the first EPSC in response to a stimulus train is

| [S1] |

where α′ was substituted for α × β. During stimulus trains release probability may change and pools get partially depleted. For simplicity, we assume that relative changes in release probability are the same for SVns and SVss. They are characterized by the factor ε(f), which is defined as the ratio of pn of the first stimulus over that at steady state. ε(f) is a function of stimulation frequency f, which most likely is close to 1, except for the highest frequencies (100 Hz and 200 Hz). We include ε(f) in the equations here for completeness, but make the simplifying assumption ε(f) = 1 in most instances, except when discussing the time course of the SVs and SVn components of EPSCs. Steady-state depletion of pools is also a function of frequency, which we denote with γ(f) for SVns and δ(f) for SVss. The functions ε(f), γ(f), and δ(f) thus represent facilitation and short-term depression of SVs. With these definitions the steady-state quantal content mss is

| [S2] |

In plots like that of Fig. 3C different synapses are assumed to differ only in α′. For the discussion of such plots it is convenient to introduce their y and x coordinates as xi = q × m1,i and yi = q × mss,i, where q is the quantal size, the subscript i denotes a given synapse, and ss refers to steady state. Also, we define the coordinates xn and yn for (hypothetical!) synapses with α′ = 0 as

| [S3] |

| [S4] |

With these definitions, using [S1] and [S2] we obtain

| [S5] |

For a given frequency this is a straight line, passing through (yn, xn), with slope ε(f) × δ(f). Thus, the slopes of line fits in Fig. 3C provide the pool depletion factors of SVss, multiplied by a facilitation factor. Likewise, considering [S3] and [S4], the ratio yn/xn is the product ε(f) × γ(f), providing the pool depletion factors of SVns, again multiplied by possible influence of facilitation. In the main text we assumed ε(f) = 1 for simplicity, which should be valid for low frequencies. However, for frequencies ≥50 Hz, there are clear indications for ε(f) > 1. (see Results for the time course of the SVs component.) The y-axis intercept, y0, of the line fit according to Eqs. S3–S5 is

| [S6] |

In this equation ε(f) × δ(f) and y0 are known, such that it establishes a relationship between ε(f) × γ(f) and xn. Thus, we cannot determine any of the two quantities individually. If, however, an assumption is made for one of them, for instance 0.8 < ε(f) × γ(f) < 1, we can determine upper and lower bounds for xn. Using a 1-Hz line fit to control data [y0 = −0.152 nA; δ(1) = 0.489] and assuming ε(f) = 1, we obtain

| [S7] |

This result confirms the qualitative conclusions in the main text about the size of the SVn pool under the likely assumption, that for all frequencies ≤1 Hz there is neither appreciable facilitation nor depletion of the SVn pool, unless there are compensatory changes.

Kinetics of Priming.

For a quantitative analysis of priming processes (normal priming and superpriming) we make the simplest possible assumption, namely that both SV pools are consumed and refilled independently according to a first-order reaction scheme

| [S8] |

Here, k+,i are the rate constants of refilling of the respective pool and pi × f is the product of frequency and release probability (i refers to either the superprimed or the nonsuperprimed pool). This leads to the equation

| [S9] |

where the subscript ss refers to steady state. Writing this equation for the two pools considered here, with the definition of pn, including its frequency dependence ε(f) (Eq. S1), and introducing the definitions

| [S10] |

we obtain from [S3], [S4], [S9], and [S10]

| [S11] |

and for the slope s(f) of Fig. 3C

| [S12] |

The fit of Fig. 4B was calculated according to Eqs. S10 and S12, once for a fixed value of k+,s of 0.8 s−1 and once for a frequency-dependent one:

ε(f) was assumed to be 1, which is expected to hold, except for the highest frequencies of 100 Hz and 200 Hz.

SI Materials and Methods

Slice Preparation.

Juvenile, posthearing (P13–16) Wistar rats of either sex were used for most experiments. Brainstem slices were prepared as previously described (35). In short, after decapitation, the whole brain was immediately immersed into ice-cold low Ca2+ artificial CSF (aCSF) containing 125 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, 25 mM NaHCO3, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 0.4 mM ascorbic acid, 3 mM myo-inositol, and 2 mM Na-pyruvate, pH 7.3, when bubbled with carbogen (95% O2, 5% CO2). The brainstem was glued onto the stage of a VT1000S vibratome (Leica) and 200-μm thick coronal slices containing the MNTB were cut. Slices were incubated for 30–40 min at 35 °C in an incubation chamber containing normal aCSF and kept at room temperature (22–24 °C) for up to 4 h thereafter. The composition of normal aCSF was identical to that of low Ca2+ aCSF except that 1.0 mM MgCl2 and 2.0 mM CaCl2 were used.

Electrophysiology.

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made from calyx of Held terminals and principal neurons of the MNTB, using an EPC-10 amplifier controlled by Pulse software (HEKA Elektronik). Sampling intervals and filter settings were 20 μs and 5.0 kHz, respectively. Cells were visualized by infrared-differential interference contrast microscopy through a 40× water-immersion objective, using an upright microscope (Olympus BX51WI). During experiments, slices were continuously perfused with normal aCSF solution. All experiments were carried out at room temperature (22–24 °C). For postsynaptic recordings, patch pipettes were pulled from thin-walled glass (World Precision Instruments) on a PIP-5 puller (HEKA Elektronik). Open tip resistance was 2.5–3.5 MΩ. Rs ranged from 4 MΩ to 7 MΩ. Rs compensation was set to ≥84% (2 μs delay). The holding potential was −70 mV. Pipettes were filled with a solution consisting of the following: 140 mM Cs-gluconate, 20 mM TEA-Cl, 10 mM Hepes, 5 mM EGTA, 5 mM Na2-phosphocreatine, 5 mM ATP-Mg, 0.3 mM GTP, pH 7.3, with CsOH. No corrections were made for liquid junction potentials.

EPSCs were elicited by afferent fiber stimulation via a bipolar stimulation electrode placed halfway between the brainstem midline and the MNTB. Stimulation pulses (100 μs duration) were applied using a stimulus isolator unit (AMPI), with the output voltage set to 1–2 V above threshold for AP generation (≤25 V) to exclude stimulation failures at higher frequencies. For each AP-evoked EPSC the series resistance (Rs) value was updated and stored with the data, using the automated Rs compensation routine implemented in Pulse. Postsynaptic recordings with a leak current >300 pA were excluded from the analysis. For clarity, stimulation artifacts were blanked for the EPSCs displayed in Figs. 1 and 5.

A total of 1 mM kynurenic acid was added to the bath solution to minimize AMPAR desensitization and saturation in the experiments illustrated in Figs. 1–5. Nevertheless, indications of residual desensitization were apparent in some recordings, particularly in those with large EPSCs. For instance, in Fig. 5D the line fits to data from PTP experiments intersect at smaller initial EPSC amplitudes than those in Fig. 3C. This result is most likely due to differences in slope of the line fits to the 100-Hz scatter plots. Desensitization in strongly potentiated synapses may be the cause for a negative slope of the plot in Fig. 5D. (For another indication of desensitization see Fig. 4A legend.)

In Fig. 5 A and C data are presented for four time intervals, relative to the induction of PTP. For EPSC trains without preconditioning these time intervals were selected as follows: before, average of five trains immediately before induction of PTP; early, average of two trains at 45 s and 75 s after tetanus onset; medium, average of three trains at 105 s, 135 s, and 165 s after tetanus onset; and late, average of three trains at 255 s, 285 s, and 315 s after tetanus onset.

Preconditioned 100-Hz trains were acquired 15 s earlier than the respective values given above.

Offline analysis was performed using Igor Pro (Wavemetrics). Remaining series-resistance errors were corrected (67) using the Rs values stored in the data files (assuming a linear IV relationship with a reversal potential of +10 mV). EPSCs were subsequently offset corrected and low-pass filtered (fcutoff = 5 kHz), using a 10-pole software Bessel filter. Original data are presented as mean ± SEM. SDs of fitting parameters are given, as supplied by Igor Pro curve-fitting algorithms. For derived quantities (products, ratios, etc.) SEM was calculated assuming Gaussian error propagation.

Glutamate Sensor and Optical Recordings.

Primary hippocampal cultures were prepared from 1-d-old Wistar rats according to the regulations of the Max Planck Society and plated on poly-d-lysine–coated coverslips. Calcium phosphate-mediated transfection of neurons with iGLuSnFR (Addgene plasmid 41732) was performed at 3 DIV. All imaging experiments were performed at DIV 14–21 at room temperature (22–24 °C). During measurements neurons were perfused with modified Tyrode’s solution (140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 3 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose, 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4). A total of 10 µM 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2, 3-dione (CNQX) and 50 µM d, l-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (AP5) were added to prevent recurrent activity.

Coverslips were mounted in a custom imaging chamber on the stage of a Nikon TE2000 inverted microscope. iGluSnFR fluorescence was excited with a 488-nm diode laser (Coherent) and emission was imaged with a Zyla 5.5 sCMOS camera (Andor Technology) at 100 Hz through a 60×, 1.2 NA Plan Apo objective, using a 510-nm dichroic and 515–560-nm emission filter. Action potentials were evoked by 1-ms current pulses (WPI A 385; World Precision Instruments), yielding a 10 V/cm field between two platinum electrodes. Timing of stimuli was controlled by a Master 8 pulse generator and triggered by computer-controlled TTL output. Image acquisition and hardware synchronization were controlled by Andor IQ2. Image analysis was performed in Matlab.

Acknowledgments

We thank Manfred Lindau for valuable discussions and comments on the manuscript, F. Würriehausen for expert advice on programming, and I. Herfort for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by the Cluster of Excellence and Center for Nanoscale Microscopy and Molecular Physiology of the Brain (E.N., A.W., and H.T.), the European Commission (EUROSPIN, FP7HEALTHF22009241498; to E.N.), and the Max Planck Society (E.N.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1606383113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:355–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.092501.114547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chanda S, Xu-Friedman MA. Excitatory modulation in the cochlear nucleus through group I metabotropic glutamate receptor activation. J Neurosci. 2011;31(20):7450–7455. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1193-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Billups B, Graham BP, Wong AY, Forsythe ID. Unmasking group III metabotropic glutamate autoreceptor function at excitatory synapses in the rat CNS. J Physiol. 2005;565(Pt 3):885–896. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.086736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenowitz S, Trussell LO. Minimizing synaptic depression by control of release probability. J Neurosci. 2001;21(6):1857–1867. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-01857.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang T, Rusu SI, Hruskova B, Turecek R, Borst JG. Modulation of synaptic depression of the calyx of Held synapse by GABA(B) receptors and spontaneous activity. J Physiol. 2013;591(19):4877–4894. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.256875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Jong AP, Fioravante D. Translating neuronal activity at the synapse: Presynaptic calcium sensors in short-term plasticity. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:356. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Junge HJ, et al. Calmodulin and Munc13 form a Ca2+ sensor/effector complex that controls short-term synaptic plasticity. Cell. 2004;118(3):389–401. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang S, et al. Complexin stabilizes newly primed synaptic vesicles and prevents their premature fusion at the mouse calyx of held synapse. J Neurosci. 2015;35(21):8272–8290. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4841-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Südhof TC. The presynaptic active zone. Neuron. 2012;75(1):11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abbott LF, Varela JA, Sen K, Nelson SB. Synaptic depression and cortical gain control. Science. 1997;275(5297):220–224. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook DL, Schwindt PC, Grande LA, Spain WJ. Synaptic depression in the localization of sound. Nature. 2003;421(6918):66–70. doi: 10.1038/nature01248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banitt Y, Martin KA, Segev I. A biologically realistic model of contrast invariant orientation tuning by thalamocortical synaptic depression. J Neurosci. 2007;27(38):10230–10239. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1640-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mongillo G, Barak O, Tsodyks M. Synaptic theory of working memory. Science. 2008;319(5869):1543–1546. doi: 10.1126/science.1150769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von der Malsburg C, Bienenstock E. Statistical coding and short-term synaptic plasticity: A scheme for knowledge representation in the brain. In: Bienenstock E, Fogelman-Soulié F, Weisbuch G, editors. Disordered Systems and Biological Organization. Springer; Berlin: 1986. pp. 247–272. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Habets RL, Borst JG. Dynamics of the readily releasable pool during post-tetanic potentiation in the rat calyx of Held synapse. J Physiol. 2007;581(Pt 2):467–478. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.127365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castro-Alamancos MA, Connors BW. Short-term plasticity of a thalamocortical pathway dynamically modulated by behavioral state. Science. 1996;272(5259):274–277. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Jong AP, Verhage M. Presynaptic signal transduction pathways that modulate synaptic transmission. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19(3):245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee SH, Dan Y. Neuromodulation of brain states. Neuron. 2012;76(1):209–222. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takahashi T, Forsythe ID, Tsujimoto T, Barnes-Davies M, Onodera K. Presynaptic calcium current modulation by a metabotropic glutamate receptor. Science. 1996;274(5287):594–597. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi T. Dynamic aspects of presynaptic calcium currents mediating synaptic transmission. Cell Calcium. 2005;37(5):507–511. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isaacson JS. GABAB receptor-mediated modulation of presynaptic currents and excitatory transmission at a fast central synapse. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80(3):1571–1576. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.3.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hori T, Takai Y, Takahashi T. Presynaptic mechanism for phorbol ester-induced synaptic potentiation. J Neurosci. 1999;19(17):7262–7267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07262.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lou X, Korogod N, Brose N, Schneggenburger R. Phorbol esters modulate spontaneous and Ca2+-evoked transmitter release via acting on both Munc13 and protein kinase C. J Neurosci. 2008;28(33):8257–8267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0550-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wierda KD, Toonen RF, de Wit H, Brussaard AB, Verhage M. Interdependence of PKC-dependent and PKC-independent pathways for presynaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2007;54(2):275–290. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu XS, Wu LG. Protein kinase c increases the apparent affinity of the release machinery to Ca2+ by enhancing the release machinery downstream of the Ca2+ sensor. J Neurosci. 2001;21(20):7928–7936. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-07928.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basu J, Betz A, Brose N, Rosenmund C. Munc13-1 C1 domain activation lowers the energy barrier for synaptic vesicle fusion. J Neurosci. 2007;27(5):1200–1210. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4908-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korogod N, Lou X, Schneggenburger R. Presynaptic Ca2+ requirements and developmental regulation of posttetanic potentiation at the calyx of Held. J Neurosci. 2005;25(21):5127–5137. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1295-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fioravante D, et al. Protein kinase C is a calcium sensor for presynaptic short-term plasticity. eLife. 2014;3:e03011. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 29.Genc O, Kochubey O, Toonen RF, Verhage M, Schneggenburger R. Munc18-1 is a dynamically regulated PKC target during short-term enhancement of transmitter release. eLife. 2014;3:e01715. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fioravante D, Regehr WG. Short-term forms of presynaptic plasticity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2011;21(2):269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grande G, Wang LY. Morphological and functional continuum underlying heterogeneity in the spiking fidelity at the calyx of Held synapse in vitro. J Neurosci. 2011;31(38):13386–13399. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0400-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlüter OM, Basu J, Südhof TC, Rosenmund C. Rab3 superprimes synaptic vesicles for release: Implications for short-term synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2006;26(4):1239–1246. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3553-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JS, Ho WK, Neher E, Lee SH. Superpriming of synaptic vesicles after their recruitment to the readily releasable pool. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(37):15079–15084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314427110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakaba T, Neher E. Calmodulin mediates rapid recruitment of fast-releasing synaptic vesicles at a calyx-type synapse. Neuron. 2001;32(6):1119–1131. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00543-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taschenberger H, von Gersdorff H. Fine-tuning an auditory synapse for speed and fidelity: Developmental changes in presynaptic waveform, EPSC kinetics, and synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2000;20(24):9162–9173. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09162.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Debanne D, Guérineau NC, Gähwiler BH, Thompson SM. Paired-pulse facilitation and depression at unitary synapses in rat hippocampus: Quantal fluctuation affects subsequent release. J Physiol. 1996;491(Pt 1):163–176. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dobrunz LE, Stevens CF. Heterogeneity of release probability, facilitation, and depletion at central synapses. Neuron. 1997;18(6):995–1008. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murthy VN, Sejnowski TJ, Stevens CF. Heterogeneous release properties of visualized individual hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 1997;18(4):599–612. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schneggenburger R, Meyer AC, Neher E. Released fraction and total size of a pool of immediately available transmitter quanta at a calyx synapse. Neuron. 1999;23(2):399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80789-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neher E. Merits and limitations of vesicle pool models in view of heterogeneous populations of synaptic vesicles. Neuron. 2015;87(6):1131–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Müller M, Goutman JD, Kochubey O, Schneggenburger R. Interaction between facilitation and depression at a large CNS synapse reveals mechanisms of short-term plasticity. J Neurosci. 2010;30(6):2007–2016. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4378-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kopp-Scheinpflug C, Tolnai S, Malmierca MS, Rübsamen R. The medial nucleus of the trapezoid body: Comparative physiology. Neuroscience. 2008;154(1):160–170. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]