Significance

Phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinases (PIPKs) generate two highly important phosphatidylinositol bisphosphates, PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,5)P2, which are central to many signaling and membrane trafficking processes. The three types of PIPKs are homologous in sequence but demonstrate different substrate and catalytic specificities. In this study, we provide crystallographic and biochemical evidence showing that the complex pattern of substrate recognition and phosphorylation results from interplay between two structural elements: the specificity loop and the binding site for the monophosphate moiety of the substrate. This work provides the first complete understanding of how this family of lipid kinases achieves exquisite substrate specificity. The mechanistic insights presented are timely because an increasing number of studies implicate lipid kinases in major human diseases, including cancer and diabetes.

Keywords: lipid kinases, protein engineering, crystallography, substrate specificity

Abstract

The phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase (PIPK) family of enzymes is primarily responsible for converting singly phosphorylated phosphatidylinositol derivatives to phosphatidylinositol bisphosphates. As such, these kinases are central to many signaling and membrane trafficking processes in the eukaryotic cell. The three types of phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinases are homologous in sequence but differ in catalytic activities and biological functions. Type I and type II kinases generate phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate from phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate and phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate, respectively, whereas the type III kinase produces phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate from phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate. Based on crystallographic analysis of the zebrafish type I kinase PIP5Kα, we identified a structural motif unique to the kinase family that serves to recognize the monophosphate on the substrate. Our data indicate that the complex pattern of substrate recognition and phosphorylation results from the interplay between the monophosphate binding site and the specificity loop: the specificity loop functions to recognize different orientations of the inositol ring, whereas residues flanking the phosphate binding Arg244 determine whether phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate is exclusively bound and phosphorylated at the 5-position. This work provides a thorough picture of how PIPKs achieve their exquisite substrate specificity.

Phosphatidylinositol phosphate (PIP) kinases (PIPKs) are key players in the metabolism of phosphoinositides in eukaryotic cells. PIPKs are primarily responsible for the synthesis of doubly phosphorylated phosphatidylinositol (PI) derivatives from singly phosphorylated PIs (1–4). PIPK catalytic activities are important to the cell in part because they produce essential PI bisphosphates such as PI(4,5)P2, which is involved in a wide variety of signaling pathways and membrane trafficking events, and PI(3,5)P2, which has a more specialized role in endosomes (5). In addition, these kinases control the level of certain PI monophosphates such as PI(5)P, which appears to function as a stress signal (6). Mutations in PIPKs have been linked to human diseases (7, 8), and, in cancerous cells, the activities of PIPKs are often up-regulated, usually as a consequence of overexpression (9, 10).

There are three subfamilies of PIPKs that share sequence identity within the kinase domain (2). The type I kinase phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase (PIP5K), localized mainly to the plasma membrane, is responsible for synthesizing the majority of PI(4,5)P2 in the cell and accomplishes this process by phosphorylating the 5-hydroxyl group of PI(4)P (Fig. S1A). In vitro, the type I kinase also has a robust activity against PI(3)P, generating not only PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,5)P2 but also the triply phosphorylated PI(3,4,5)P3 (11, 12). Furthermore, the type I kinase can weakly phosphorylate PI to produce PI(5)P. In contrast, the type II kinase phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinase (PIP4K) is diffusively distributed in the cytoplasm and nucleus. This enzyme prefers PI(5)P as substrate, phosphorylating it at the 4-position (13). In vitro, the type II kinase also phosphorylates PI(3)P, generating PI(3,4)P2, albeit with much lower efficiency. Although both type I and type II kinases produce PI(4,5)P2, their functions are nonredundant. The type II kinase appeared later in evolution than the type I kinase, suggesting that the type II kinase has a more specialized role in higher eukaryotes. The type III kinase (PIKfyve) is a much larger enzyme that has a complex domain structure, including an N-terminal FYVE zinc finger domain, which binds PI(3)P (14, 15). The type III kinase prefers PI(3)P as its substrate and is mainly involved with the synthesis of PI(3,5)P2 in late endosomes (16). In vitro, the type III kinase demonstrates a weak activity toward PI, generating PI(5)P.

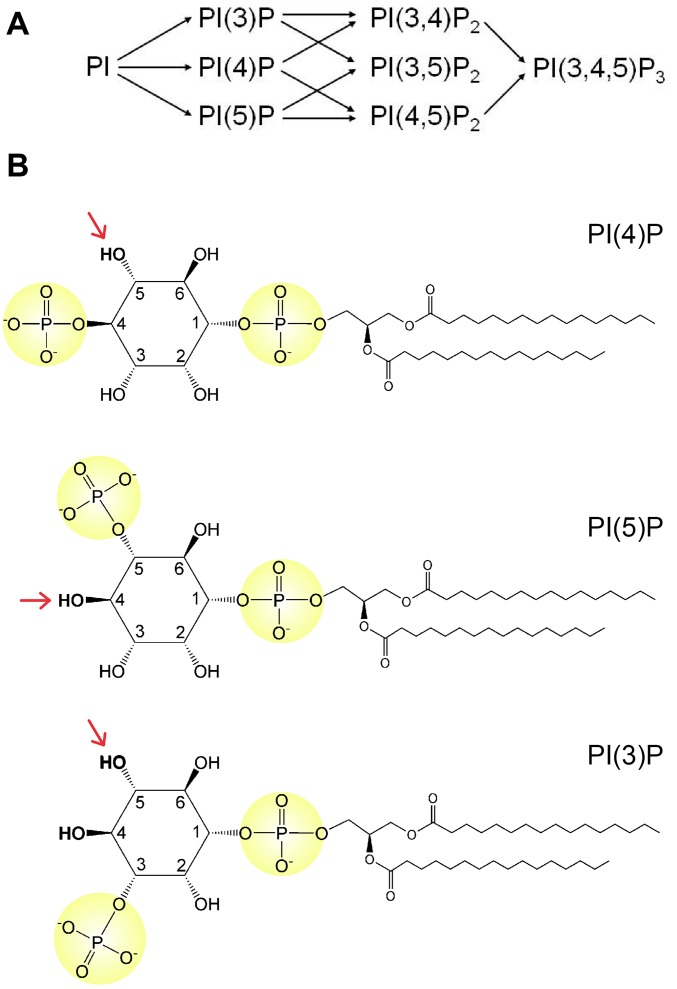

Fig. S1.

Phosphorylation of PI and PIPs. (A) Schematic depicting the synthesis of the seven phosphoinositides. (B) Chemical structures of PI(4)P, PI(5)P, and PI(3)P. The type I kinase, PIP5K, preferentially phosphorylates PI(4)P at the 5-hydroxyl (red arrow). The type II kinase, PIP4K, preferentially phosphorylates PI(5)P at the 4-hydroxyl. The type III kinase, PIKfyve, preferentially phosphorylates PI(3)P at the 5-hydroxyl.

PIPKs do not share sequence homology with protein kinases. Although crystal structures of the apo form of type I and type II kinases have been solved (17, 18), there are, as of yet, no structural data for the kinases’ complexes with substrate, hindering a deeper understanding of the catalytic mechanism. One particularly intriguing question relates to how these kinases achieve signaling specificity; the kinases must distinguish highly similar PIP substrates and phosphorylate the substrates at distinct sites (19) (Fig. S1B). Here, we report the X-ray structure of a type I kinase in complex with adenylyl-imidodiphosphate (AMP-PNP) and discuss the structure’s implications for the kinase mechanism. We also describe the binding site for the singly phosphorylated PI, which cooperates with the specificity loop to influence substrate binding and phosphorylation.

Results and Discussion

The Binding of ATP.

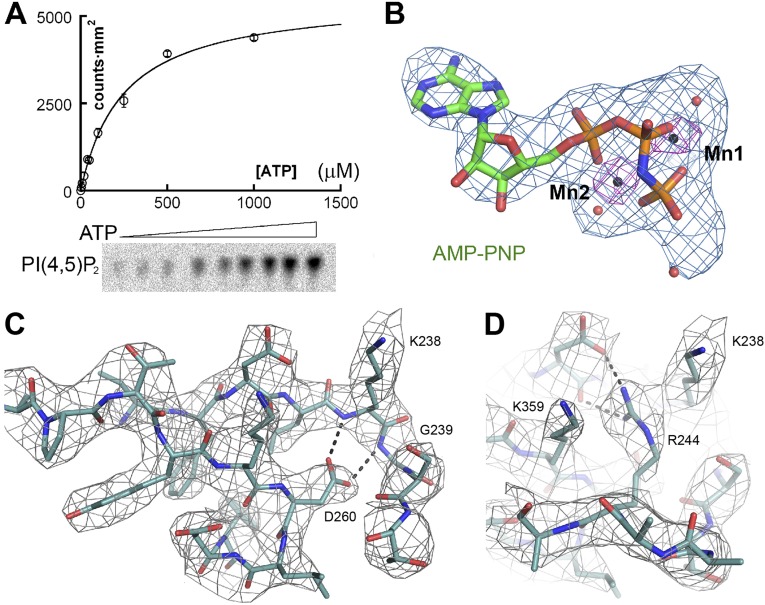

Dimerization of PIP5Kα involves helix α4, which is equivalent to the “C helix” of protein kinases that often plays a role in allosteric regulation (20, 21). We measured the initial rates of PI(4,5)P2 production from PI(4)P at different ATP concentrations and found that the reaction follows simple Michaelis–Menten kinetics, with no cooperativity in ATP binding (Fig. S2A). We solved the X-ray crystal structure of the zebrafish PIP5Kα in complex with the ATP analog AMP-PNP by soaking the analog into preformed crystals. Difference Fourier analysis confirmed the presence of the analog bound at the predicted ATP binding site (Fig. S2B). Two manganese ions (Mn2+), bound by AMP-PNP, were clearly visible as 8σ peaks in the anomalous Fourier map because of the anomalous diffraction of manganese at the wavelength of data collection (1.075 Å). The position of the metal ions facilitated the building of AMP-PNP into the 3.3-Å resolution electron density map. Improved crystallization condition also enabled us to extend the resolution of the apo structure to 3.1 Å, which was used as the starting point for model building and refinement (Table S1 and Fig. S2 C and D).

Fig. S2.

ATP binding and electron density maps. (A) Plot of the initial reaction velocity of PI(4,5)P2 production by PIP5Kα as a function of ATP concentration. (B) The 2Fo-Fc electron density map for AMP-PNP, contoured at a level of 3σ. The anomalous difference Fourier map for the manganese ions, contoured at a level of 5σ, is shown in pink. (C and D) The 2Fo-Fc maps for Asp260, Arg244, and neighboring residues, contoured at a level of 1.2σ.

Table S1.

Crystallographic statistics

| Data collection | Native | AMP-PNP | AMP-PNP/selenate |

| Wavelength, Å | 1.075 | 1.075 | 0.9788 |

| Cell dimensions, Å | a = b = 88.9, c = 154.6 | a = b= 87.9, c = 156.5 | a = b = 88.1, c = 155.8 |

| Resolution,* Å | 40–3.1 (3.2–3.1) | 40–3.3 (3.4–3.3) | 40–3.6 (3.7–3.6) |

| Redundancy,* | 9.3 (9.7) | 9.3 (9.6) | 13.6 (14.0) |

| Completeness,* % | 99.6 (100) | 99.5 (99.3) | 100 (100) |

| <I/σ>* | 11.3 (1.2) | 9.9 (2.8) | 5.5 (5.2) |

| Rmerge*,† | 0.073 (0.678) | 0.078 (0.898) | 0.152 (0.584) |

| Refinement | |||

| Unique reflections | 11,844 | 9,831 | 7,655 |

| No. of atoms | |||

| Protein | 2,327 | 2,268 | 2,268 |

| Ligand | — | 36 | 45 |

| Rwork/Rfree‡ | 0.210/0.273 | 0.204/0.272 | 0.202/0.262 |

| B-factor, Å2 | 83 | 103 | 84 |

| rmsd | |||

| Bond lengths, Å | 0.014 | 0.012 | 0.010 |

| Bond angles, ° | 1.863 | 1.746 | 1.568 |

Space group is P43212.

Highest resolution shell is shown in parentheses.

Rmerge = ∑ | Ii - <I> |/∑ Ii.

Rwork = ∑ | Fo – Fc |/∑ Fo. Rfree is the cross-validation R factor for the test set of reflections (5% of the total) omitted in model refinement.

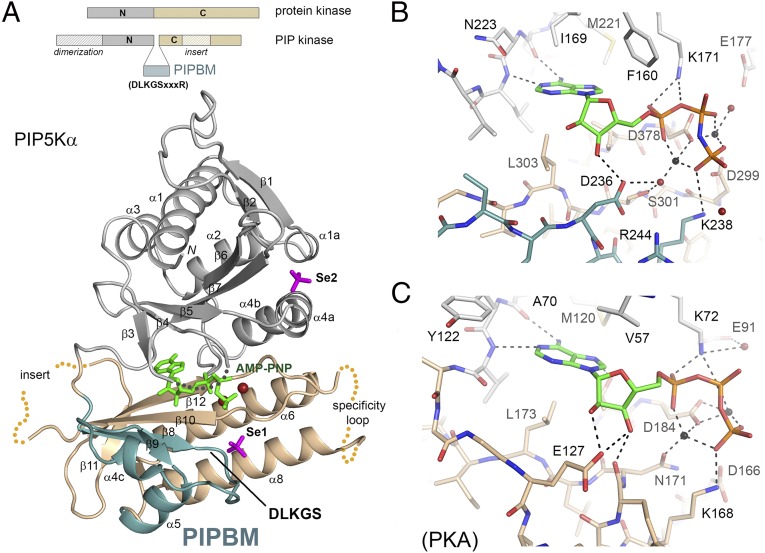

In PIPKs, the ATP binding site is flanked not only by the N- and C-lobes of the kinase but also by a substructure that is unique to the family (blue in Fig. 1A). In the primary sequence, this unique segment is inserted between the two lobes. The segment is composed of two parallel β-strands (β8, β9) and two short helices (α4c, α5). Strands β8 and β9 form a continuous sheet with β10, the counterpart of the “catalytic loop” of protein kinases. The “DLKGS” sequence motif, conserved in all PIPKs, is located at the tip of the substructure between β8 and α4c. The substructure is one of the most conserved regions of the enzyme, because it harbors 5 of the 22 invariant residues in the family: Asp236, Lys238, Gly239, Arg244, and Asp260. Gly239 and Asp260 mainly play a structural role: the flexible glycine is located at the turn between β8 and α4c, whereas Asp260 maintains the shape of the turn by forming hydrogen bonds with two backbone amide groups (Fig. S2C). Asp236, Lys238, and Arg244 contribute directly to substrate binding and catalysis, described below.

Fig. 1.

Overall structure and ATP binding site. (A) Domain organization. The schematic compares PIPKs with protein kinases. The overall structure of the zebrafish PIP5Kα in complex with AMP-PNP is shown below the schematic with the N-lobe (gray), the C-lobe (light tan), and the PIPB domain (blue). Disordered regions of the protein are indicated by dotted curves. Bound AMP-PNP and SeO42− are shown as stick models. (B) Structural details of the ATP-binding site of PIP5Kα. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by dotted lines. Red spheres represent water, and black spheres represent metal ions. (C) ATP-binding site of protein kinase A (PDB ID code 1ATP). Structural illustrations were all generated on PyMOL.

The N1 and N6 atoms of the adenine ring of AMP-PNP are hydrogen-bonded to the linker (Asn222 and Leu224), which has an identical conformation as that of protein kinase A (PKA) (22) (Fig. 1 B and C), although the segment following the linker adopts a different fold in PIPKs to accommodate the unique substructure. Lys171 (the “IIK” motif), Asp299 (“MDYSL”), and Asp378 (“IID”) of PIP5Kα are functional equivalents of Lys72 (the “VAIK” motif of protein kinases), Asp166 (“HRD”), and Asp184 (“DFG”) of PKA (underlined residues identify the amino acid of interest). Lys171 is located within a β-strand (β5) that is structurally equivalent to β3 of PKA, and its side chain points into the active site to bind the α-phosphate of ATP. Asp299, from a segment equivalent to the catalytic loop, is positioned next to the γ-phosphate of ATP and could function as the general base to receive the proton from the attacking 5-hydroxyl of PI(4)P. Asp378 contributes to the coordination of the two Mn2+ ions.

The X-ray structure also reveals features within the ATP binding pocket that are unique to PIPKs. The side chain of Lys238 from the DLKGS motif points up toward the γ-phosphate and interacts with it (Fig. 1B). The position of Lys238 superposes well with that of Lys168 in PKA. We propose that Lys238 provides a positive charge to stabilize the reaction transition state, a role traditionally assigned to Lys168 of PKA (23). Asp236 from the DLKGS motif also plays a role in substrate binding by forming a hydrogen bond with the 2-hydroxyl of the ribose. Furthermore, Asp236, together with Ser301 from the MDYSL motif, appears to contribute to metal coordination through a water molecule, thus substituting the function of Asn171 in PKA.

In PIP5Kα, AMP-PNP binding causes the ends of β3 and β4 to move down slightly toward the ligand. The turn between the two β-strands corresponds to the glycine-rich loop of PKA, which interacts with the β- and γ-phosphate groups of ATP via its backbone amides (20). In the structure of PIP5Kα in complex with AMP-PNP, however, the β3-β4 turn remains poorly defined in the electron density map and may not contribute to ATP binding. Compared with PKA, the two β-strands in PIP5Kα are also positioned further away from ATP, which generates a more open substrate binding site. This feature is partly attributable to Phe160 from β4, which is conserved in all PIPKs. The side chain of Phe160 packs tightly against the adenine and ribose. In protein kinases, the corresponding residue often has a smaller side chain (e.g., Val57 in PKA), allowing the β-strand to be positioned closer to ATP.

The Phosphate-Binding Site.

Singly phosphorylated PI derivatives are the preferred substrates for the PIPK family of enzymes. This fact suggests that PIPKs possess a structural feature to recognize the monophosphate on the inositol ring and that the binding of the phosphate group must be of sufficient affinity so that the enzyme can distinguish PIP from PI, which is much more abundant in the cell (1). Crystals soaked with soluble forms of PI(4)P with shorter lipid tails did not reveal a convincing density in the active site. To identify the phosphate binding pocket, we soaked selenate (SeO42−), an isostere of the phosphate ion (HPO42−), into PIP5Kα crystals and collected diffraction data at the selenium edge. The anomalous Fourier map revealed four positive peaks. Two correspond to manganese, which also has anomalous signal at the selenium wavelength. The other two correspond to selenate ions (Fig. 1A). One of the selenates (labeled as “Se1”) is bound to Lys238 and Arg244 at the active site, adjacent to the γ-phosphate of AMP-PNP (Fig. 2A).

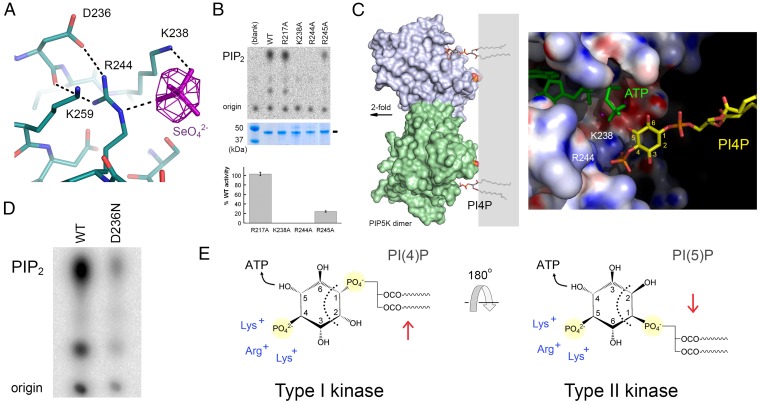

Fig. 2.

The monophosphate binding site. (A) Binding site for SeO42−. The difference Fourier map, shown in purple, is contoured at 5σ. Hydrogen bonds are indicated (dotted black lines). (B) Comparison of wild-type and mutant activities. R217A contains a mutation at the Se2 site, located in the N-lobe of the protein. In the autoradiograph shown (B, Top), spots corresponding to the origin and the radioactive product, PI(4,5)P2, are indicated. (B, Middle)The amount of kinase used for the reaction. (B, Bottom) Quantification of the relative intensities of the PI(4,5)P2 spots, averaged over a triplicate of experiments. (C) Model of the dimeric PIP5Kα bound to PI(4)P embedded in membrane bilayer (gray box). Monomers are colored blue and green. The black oval depicts the twofold axis. (Right) The active site colored according to electrostatic potential. The active site appears open due to the disordered specificity loop. PI(4)P is depicted in stick model, and C1-C6 atoms of the inositol head group are labeled. PI(4)P is modeled into the active site by superimposing the 4-phosphate onto the Se1 bound at the active site. The 5-hydroxyl is near the γ-phosphate of ATP (green) for phosphorylation. The model projects the lipid tails into the membrane bilayer. (D) Autoradiograph comparing the activities of the D236N disease mutant and wild-type PIP5Kα. Approximately 10-fold more of the mutant was used than the wild type in this assay. (E) Model depicting the role of the specificity loop in recognizing different orientations (red arrows) of the lipid substrates.

Lys238 and Arg244, which coordinate Se1 at the active site, are absolutely conserved among PIPKs. They both come from the substructure unique to the PIPK family: Lys238 is part of the DLKGS sequence motif, whereas Arg244 is invariably three residues downstream. The possibility that Lys238 and Arg244 constitute the binding site for the monophosphate on the inositol head group is supported by modeling PI(4)P into the active site of PIP5Kα (Fig. 2C): superposing the 4-phosphate group onto the bound selenate allows the 5-hydroxyl to move into an ideal position to conduct nucleophilic attack on the γ-phosphate of ATP while maintaining the lipid tails in the membrane bilayer.

To experimentally test whether these residues are important for kinase function, we separately mutated them to alanine together with seven other positively charged residues in the vicinity of the active site. Of the four mutants that could be purified, K238A and R244A completely abolished activity (Fig. 2B). The effect of the K238A mutation can be twofold, because the lysine also contributes to ATP binding, in addition to the binding of lipid substrate. The counterpart of Lys238 in protein kinases, Lys168 of PKA, also plays a part in the binding of the non-ATP substrate (23). Arg244, on the other hand, appears to play a dedicated role in binding the 4-phosphate of the lipid substrate. The R244A mutation does not hinder the intrinsic ATPase activity of the kinase (Fig. S3). We named the unique substructure containing the “DLKGSxxxR” sequence as the PIP-binding motif (PIPBM) because of its conservation within the PIPK family and its role in recognizing the monophosphate on PIP.

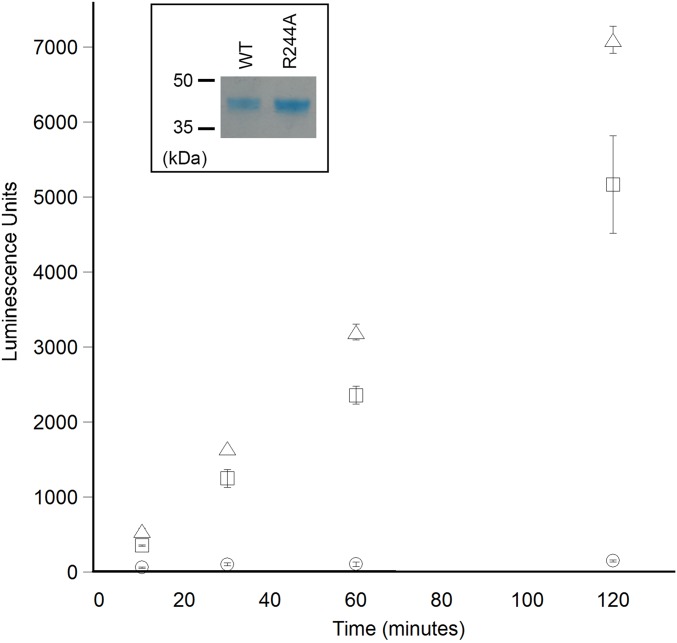

Fig. S3.

ATPase assay comparing wild-type PIP5Kα and R244A. The R244A mutant (triangle) hydrolyzes ATP at a rate similar to that of the wild-type enzyme (square). Assay conducted without kinase (circle) are also shown as a control.

Mutation and Human Disease.

A single mutation (D253N) within the kinase domain of human PIP5Kγ causes a severe form of arthrogryposis called lethal congenital contracture syndrome type 3 (LCCS3) (8). LCCS3 is characterized by atrophy in the patient’s spinal cord and multiple joint contractures. The γ isoform of the type I kinase is highly expressed in the brain and is essential for survival (24, 25). The disease phenotype appears to be related to perturbed phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling, which could result from reduced PI(4,5)P2 production, because LCCS2, a condition similar to LCCS3, is caused by the mutation of a protein involved in PI3K activation (26). Asp253 of human PIP5Kγ corresponds to Asp236 in the zebrafish PIP5Kα, the first residue within the DLKGS sequence motif. We mutated Asp236 to asparagine and found that the mutant, although still capable of converting PI(4)P to PI(4,5)P2 in vitro, has an activity three orders of magnitude lower than that of the wild type (Fig. 2D). The X-ray structure suggests that the mutation disrupts a salt bridge between Asp236 and Arg244, thus possibly affecting the conformation of the latter (Fig. 2A). Arg244 is important for the recognition of PIP substrate. The D236N mutation may also affect hydrogen bonding between Ser301 and the 2-hydroxyl of the ribose ring on ATP (Fig. 1B). Because asparagine retains the hydrogen bonding potential of aspartate, the loss of a negative charge, which should mostly impact the salt bridge with the positively charged arginine, is probably the main reason for the 1,000-fold loss of catalytic activity we observed.

Mutations in other PIPKs also play roles in human disease. For example, in the type II kinase PIP4Kα, there is a polymorphism (N251S) within the kinase domain that is associated with increased risk for schizophrenia (27). The mechanism is unclear because Asn251 is located near the amino terminus of α6, away from the ATP and lipid binding sites. In vitro, the N251S mutation does not affect kinase activity. The type III kinase PIKfyve harbors several mutations that cause fleck corneal dystrophy (7). Most of these induce frameshifts and truncations near the middle of this large protein, completely eliminating the kinase domain that is located at the carboxyl terminus.

Kinase Specificity.

We propose that the phosphate binding site depicted in Fig. 2A is a general feature for the family. In order for the 4-phosphate of PI(4)P, the preferred substrate for the type I kinase, and the 5-phosphate of PI(5)P, preferred by the type II kinase, to interact with the same binding site while maintaining the reactive 5-hydroxyl of PI(4)P and 4-hydroxyl of PI(5)P close to ATP, the inositol ring must flip 180° around a horizontal line passing through the center of the PIP (Fig. 2E). Type I and type II kinases differ in amino sequence at a key position within the specificity loop (28). The function of residue appears to be to distinguish the two lipid orientations by interacting with chemical groups on the substrate that face the membrane, including the 1-phosphate, axial 2-hydroxyl, and diglyceride (located to the right of the dotted lines in Fig. 2E). The chemical structure left of the dotted line for PI(4)P and for PI(5)P is completely identical and is recognized by the structurally similar kinase core for the phosphoryl transfer reaction.

The conformations of Lys238 and Arg244 in the type I kinase PIP5Kα differ from their counterparts in a type II kinase, PIP4Kβ [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 1BO1; Fig. S4 A and B]. This difference appears to be attributable to crystallization instead of difference between subfamilies. In the reported structure of PIP4Kα (PDB ID code 2YBX; Fig. S4C), the conformations of the lysine and arginine are similar to those in PIP5Kα. In this structure, there is also a phosphate ion modeled between Lys238 and Arg244. Compared with the bound SeO42−, the phosphate is shifted slightly to the left and forms an additional interaction with the counterpart of Lys259. Lys259, unlike Lys238 and Arg244, is conserved only in type I and type II kinases. Additional experiments, explained below, indicate that this residue contributes to the preference of type I and type II PIPKs to phosphorylate the hydroxyl adjacent to the monophosphate already present on the substrate.

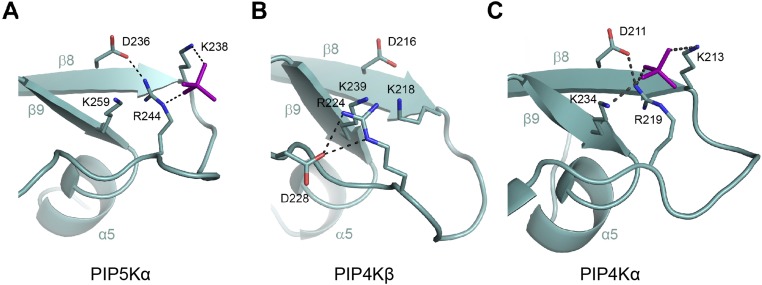

Fig. S4.

Comparison of the monophosphate binding sites. (A) Zebrafish PIP5Kα. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dotted lines. (B) Human PIP4Kβ (PDB ID code 1BO1). (C) Human PIP4Kα (PDB ID code 2YBX). A bound phosphate ion is shown in purple, and this phosphate is coordinated by Arg219, the counterpart to Arg244 in PIP5Kα.

The mechanism proposed above predicts three structural features that determine lipid substrate specificity: (i) The ATP binding site: although ATP is probably bound identically throughout the family, the lipid has to be arranged in such a way that the reactive hydroxyl group is near the γ-phosphate of ATP. (ii) The PIPBM: this motif underlies the preference of the family for singly phosphorylated PIs. The inositol ring has to flip 180° to project the phosphate, attached to hydroxyls at different positions on the inositol head group, into the common binding pocket. In PI3K, it was predicted that the 4- and 5-phosphates on the inositol head groups are recognized by residues on the activation loop (which corresponds to the specificity loop of PIPKs) (29). (iii) The specificity loop: the ATP and phosphate binding sites dictate how the lipid should be oriented for chemical reaction with ATP, whereas the specificity loop functions to recognize the orientation of the lipid instead of directly scrutinizing the lipid’s phosphorylation status. A summary of how various PIP substrates bind to the type I, type II, and type III kinases is provided in Fig. S5.

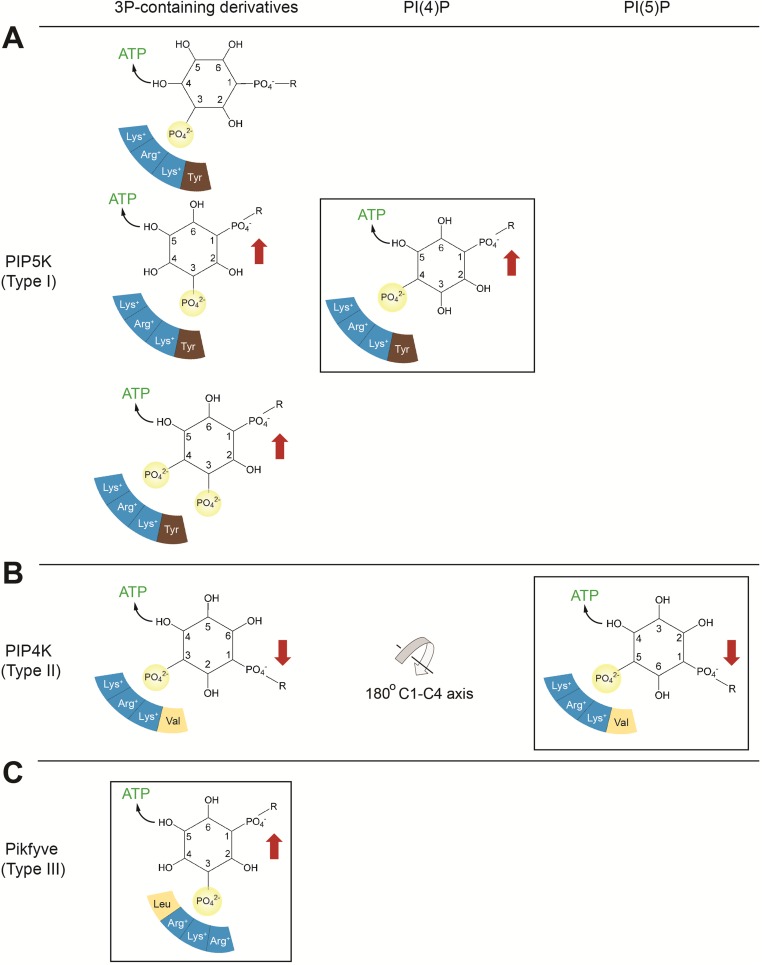

Fig. S5.

Substrate specificity of PIP5K (type I), PIP4K (type II), and PIKfyve (type III). The preferred reaction of each kinase is boxed, and residues of the monophosphate binding site are represented by colored segments, with blue indicating positively charged residues. Red arrows indicate the orientation of the lipid substrate preferred by the specificity loop of each kinase. (A) PIP5K. PIP5K prefers PI(4)P, phosphorylating the 5-hydroxyl, with the 1-phosphate of PI(4)P projecting upward. PIP5K contains a glutamate (Glu382 of PIP5Kα) in the specificity loop, which recognizes the upward orientation of the 1-phosphate. PIP5K cannot phosphorylate the 4-hydroxyl of PI(5)P because this phosphorylation would require the 1-phosphate to project downward. In addition, PIP5K can phosphorylate PI(3)P, generating PI(3,4)P2, PI(3,5)P2, and PI(3,4,5)P3. In the minor reaction that generates PI(3,4)P2, the positions of the 4-hydroxyl and 1-phosphate are not ideal for nucleophilic attack and compatibility with the specificity loop. (B) PIP4K. The alanine (Ala-371 of PIP4Kα) in the specificity loop favors the downward orientation of the 1-phosphate of PI(5)P. A 180° flip around the C1-C4 axis allows the 1-phosphate of PI(3)P to also point downward, compatible with the specificity loop of PIP4K (18). In this orientation, only the 4-hydroxyl can react with ATP. (C) PIKfyve. Compared with PIP5K and PIP4K, PIKfyve features a different arrangement of residues at the phosphate binding site, as shown, causing a slight shift. This shift renders PIKfyve incapable of phosphorylating PI(4)P. The specificity-switch residues of PIKfyve, and thus PIKfyve’s preference for the upward substrate orientation, are identical to those of PIP5K. PIKfyve phosphorylates PI(3)P exclusively at the 5-position.

We tested this model of substrate specificity by trying to engineer the specificity of the type III kinase into the type I kinase PIP5Kα. Unlike type I or type II kinases, the type III kinase (PIKfyve) prefers PI(3)P as its substrate and phosphorylates the 5-hydroxyl, skipping the 4-hydroxyl. Our proposed model predicts that residues responsible for a type III-like specificity must lie adjacent to the phosphate binding site because the specificity loop of type III kinase has the same “specificity switch” (Glu382 in PIP5Kα) as the type I kinase, suggesting that the orientation of PI(3)P bound to the type I kinase is similar to that of PI(4)P (Fig. 3A). After studying the aligned PIPBM sequences, we identified two sequence motifs that are conserved in type III kinases and adjacent to Arg244 in the 3D structure (Fig. 3A). In type III kinases, the “RxR” sequence motif introduces an arginine (which would be Arg242, according to PIP5Kα numbering) upstream of the universally conserved Arg244. This Arg242 replaces a mostly hydrophobic residue in type I and type II kinases. The second sequence motif we identified in type III PIPKs, the “LD” motif, replaces Lys259 of PIP5Kα, a conserved residue in type I and type II kinases, with a leucine. The net consequence of these substitutions is to shift the positively charged binding pocket to the right, subtly altering the position of the phosphate binding site relative to ATP.

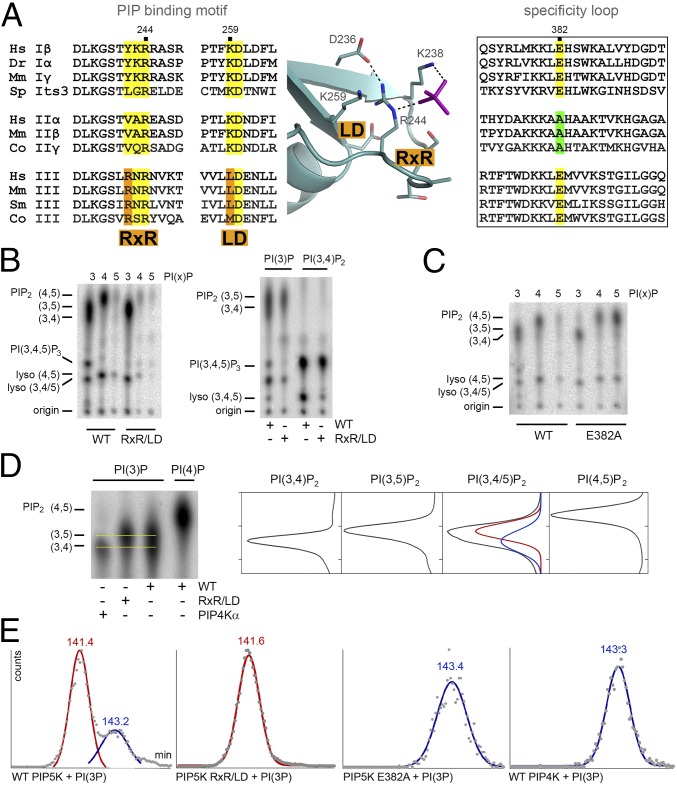

Fig. 3.

Substrate specificity. (A) Sequence alignment of the monophosphate binding sites and the specificity loops (boxed) of type I, II, and III PIPKs, with the RxR and LD motifs as well as the specificity-switch residues highlighted. The names of organisms are abbreviated as follows: Co, Capsaspora owczarzaki (XP_004364933.1 and KJE93967.1); Dr, Danio rerio (AAH95318.1); Hs, Homo sapiens (AAH30587.1 and AAH18034.1 and Q9Y2I7.3); Mm, Mus musculus (NP_032870.2 and AAH47282.1 and NP_001297553.1); Sm, Stegodyphus mimosarum (KFM78861.1); and Sp, Schizosaccharomyces pombe (CAB10125.1). Residues are numbered according to the zebrafish PIP5Kα, and the locations of the RxR and LD motifs are shown in the context of the PIP5Kα structure. (B) Assay of wild-type PIP5K and the RxR/LD mutant. PI(3)P, PI(4)P, or PI(5)P was used as substrate (Left), and the lanes on the TLC plate are arranged in this order. To obtain greater resolution, the TLC plates were run for 3 h. The locations of PI(4,5)P2, PI(3,5)P2, PI(3,4)P2, PI(3,4,5)P3, lyso-PI(4,5)P2, and lyso-PI(3,4)P2 or lyso-PI(3,5)P2 are indicated. The assay using PI(3)P or PI(3,4)P2 as substrate (Right) shows that the RxR/LD mutant is fully capable of phosphorylating PI(3,4)P2, generating PI(3,4,5)P3. (C) Assay of wild-type PIP5K and the E382A mutant with PI(3)P, PI(4)P, or PI(5)P as substrate. PIP5Kα E382A harbors the specificity switch mutation. (D) Detailed view of the migration of PI(3,4)P2, PI(3,5)P2, and PI(4,5)P2 by TLC, as generated by wild-type PIP5Kα, the PIP5Kα RxR/LD mutant, or wild-type PIP4Kα. The yellow lines indicate the centroids of the spots for PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,5)P2. The intensity of each spot as a function of the migration along the TLC plate (y axis) is shown on the right. The curve corresponding to the sample of PI(3)P phosphorylated by wild-type PIP5Kα was deconvoluted by calculating two Gaussian curves using the peak locations for PI(3,4)P2 (blue) and PI(3,5)P2 (red). (E) HPLC elution profiles of phosphorylation products generated by wild-type PIP5Kα, RxR/LD, E382A, and wild-type PIP4Kα. The measured radioactivity (gray dots) and the calculated Gaussian curves are shown. The internal standard of PI(3,4)P2 runs at 143.5 min (blue) and that of PI(3,5)P2 runs at 141.5 min (red). The run times of the peaks in each sample are indicated.

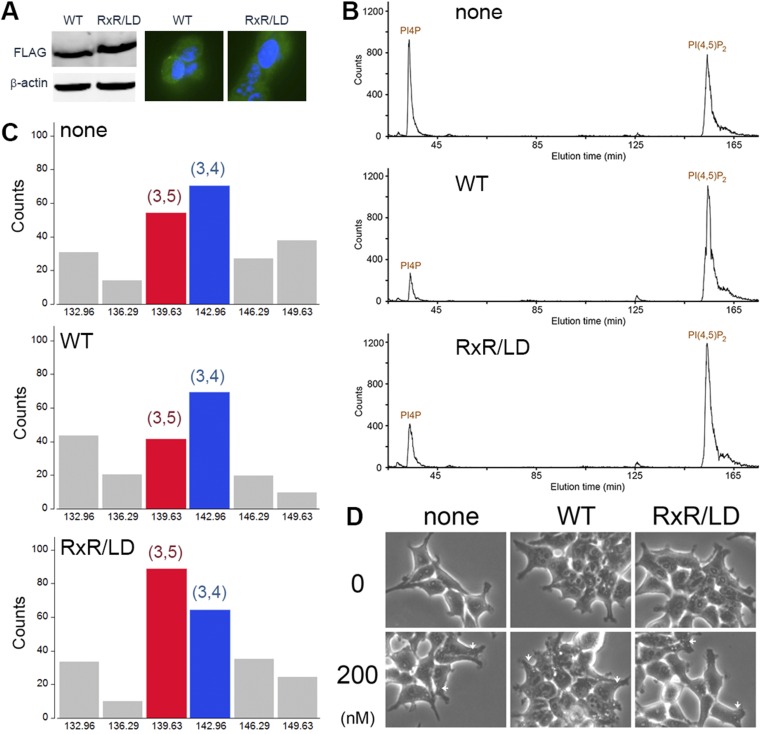

We prepared a PIP5Kα mutant (RxR/LD) that incorporates these two type III-specific motifs and flanking residues: T241L/Y242R/K243N/R245N/K259L/L261E. This mutant retains much of the catalytic activity toward PI(3)P of the wild-type enzyme but becomes much less efficient in phosphorylating PI(4)P (Fig. 3B). In agreement with previous studies of the human enzyme (11, 12, 30), the zebrafish PIP5Kα generates PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,5)P2 from PI(3)P, which comigrate on thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate as an elongated spot just below PI(4,5)P2. PI(3,4)P2 is further phosphorylated by the type I kinase to triply phosphorylated PI(3,4,5)P3, which migrates close to lyso-PI(4,5)P2. The phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate (PIP2) product generated by the type III-like RxR/LD mutant does not have the elongated shape, and the PI(3,4,5)P3 spot is also missing. Because the mutant is fully capable of phosphorylating PI(3,4)P2 (Fig. 3B), the missing PI(3,4,5)P3 indicates that PI(3,4)P2 is not produced in the first phosphorylation reaction. This finding is confirmed by running the TLC for a longer time, which shows that the PIP2 product generated by the mutant migrates between PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4)P2. PI(3,4)2 is generated from PI(3)P by the type II kinase PIP4Kα (Fig. 3D). Deacylation of the phosphorylated lipids and HPLC analysis of the soluble head groups confirmed the conclusion of the TLC experiment (Fig. 3E). Taken together, these results indicate that, after introducing the type III-specific RxR and LD motifs, the kinase becomes type III-like, switching substrate specificity from PI(4)P to PI(3)P and phosphorylating the inositol ring exclusively at the 5-position. In cultured HEK 293T cells expressing mutant zebrafish PIP5Kα, we also observed a consistent increase in the ratio of PI(3,5)P2 over PI(3,4)P2 compared with cells expressing the wild-type kinase (Fig. S6).

Fig. S6.

The activity of wild-type PIP5Kα and RxR/LD mutant in infected HEK 293T cells. (A) Western blot detecting the Flag tag fused to the C terminus of zebrafish PIP5Kα confirms that wild-type and mutant proteins had similar expression levels. Immunofluorescence staining confirms that most cells expressed PIP5Kα: DAPI staining (blue); Flag staining (green). (B) Intracellular phosphoinositide levels were determined by [3H]inositol labeling and HPLC analysis of deacylated membrane samples. Data were normalized to the PI level, which is about 25-fold higher than that of PI(4)P and is not affected by PIP5Kα expression. The label of “none” identifies cells not infected by retrovirus. Wild-type PIP5Kα reduces PI(4)P and increases PI(4,5)P2. The mutant also causes a reduction of PI(4)P but to a smaller extent. It is intriguing that PI(4,5)P2 levels in wild-type and mutant-expressing cells are similar. It is possible that, once reaching a certain threshold, the steady state PI(4,5)P2 level becomes less sensitive to PI(4,5)P2 synthesis by the kinase: cells expressing the wild-type kinase had an almost threefold reduction of PI(4)P but only a modest 40% increase of PI(4,5)P2. (C) The RxR/LD mutant increases PI(3,5)P2 levels. Owing to low signal from PI(3)P and, consequently, from PI(3,5)P2 and PI(3,4)P2, the data were binned according to the locations of peaks corresponding to standards of PI(3,5)P2 and PI(3,4)P2 on HPLC. Time points depicted represent the midpoint of the time over which each bin was calculated, and the bins corresponding to PI(3,5)P2 and PI(3,4)P2 are labeled and colored in red and blue, respectively. (D) Treating HEK 293T cells (0, 200 nM) with YM-201636, a PIKfyve inhibitor, induces vacuole formation (white arrow). YM-201636 does not affect the in vitro activity of wild-type PIP5Kα or the RxR/LD mutant. Wild-type and mutant-infected cells also develop vacuoles upon treatment, suggesting that PI(3,5)P2 generated by the mutant either is not of sufficient amount or is not produced at the correct membrane location to prevent vacuole formation.

The specificity of PIP5Kα toward PI(3)P can be modified also by the E382A mutation within the specificity loop (Fig. 3A). In agreement with the literature (28), PIP5Kα E382A prefers PI(5)P over PI(4)P as its substrate (Fig. 3C). It should be noted that PIP5Kα E382A corresponds to the PIP5Kβ E362A mutant of the referenced study. The model proposed here predicts that the E382A mutation causes the specificity loop to prefer a different lipid orientation, which would render the kinase incapable of phosphorylating the 5-hydroxyl group because it no longer points toward ATP (Fig. S5). Therefore, in contrast with the RxR/LD mutation, E382A exclusively produces PI(3,4)P2 from PI(3)P (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, E382A is unable to generate the triply phosphorylated PI(3,4,5)P3. These data illustrate again that the complex pattern of substrate selection and phosphorylation is the result of the interplay between the PIPBM and the specificity loop (Fig. S5).

The phylogenetic relationship among type I, type II, and type III kinases is complex (31). Based on in vitro activities and the model proposed here, however, it is tempting to speculate that the evolution took two paths where a promiscuous ancestral enzyme, which probably resembles the modern day type I kinase, developed more stringent and different catalytic activities by separately acquiring mutations within the specificity loop, giving way to the type II kinase and, within the PIPBM, giving way to the type III kinase. The activities gained were then selected for specialized signaling functions in the cell.

The Specificity Loop.

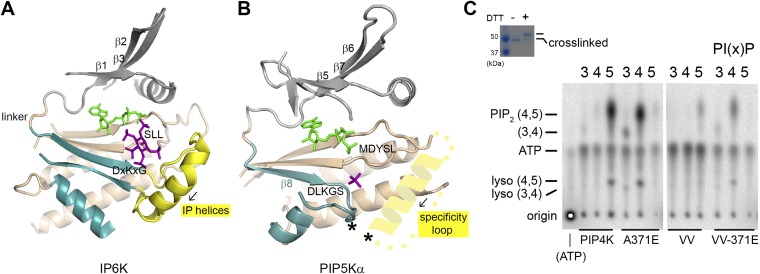

The possibility that the specificity loop interacts with the inositol from the side opposite of the monophosphate is supported by a comparison of PIPKs with inositol polyphosphate kinases (IPKs) (32, 33) (Fig. S7 A and B). IPKs are the closest structural homologs to PIPKs. Both families have a hybrid structural arrangement, with an N-lobe resembling protein kinases and a C-lobe resembling ATP-grasp enzymes (34). Although this feature alone is not unique, in that α-kinase ChaK and SAICAR synthase are also hybrids (35, 36), PIPKs and IPKs share several unusual features that distinguish them from other members of the protein kinase and ATP-grasp superfamilies. Within the N-lobe, PIP5Kα lacks the equivalent of protein kinase’s “P-loop,” which binds ATP through backbone amide groups. IPKs lack not only the P-loop, but also the preceding β-strand, and sometimes the strand that follows the loop, as well (37). Within the C-lobe, the DLKGS and MDYSL sequence motifs of PIPKs are structurally similar to the “DxKxG” and “S(L/I)L” motifs found in IPKs and play identical roles in ATP binding and catalysis. PIPKs and IPKs more closely resemble protein kinases in the “crossing loops” than ATP-grasp enzymes. In PIPKs and IPKs, the linker between the N- and C-lobes is longer and forms a protruding loop. The loop has no clear function and may be a vestigial feature from a common ancestor.

Fig. S7.

The specificity loop. (A) Structure of inositol hexakisphosphate kinase EhIP6KA in complex with ATP (green) and inositol(1,3,4,5,6)pentakisphosphate (purple) (PDB ID code 4O4E). Parts of the protein were omitted for clarity. The N- and C-lobes are colored gray and tan, respectively. Structural elements corresponding to the PIPB domain of PIPKs are colored blue. The IP helices are highlighted in yellow. (B) Structure of the zebrafish PIP5Kα with a schematic of the specificity loop capping the active site from the side of the membrane. The predicted helical segment within the specificity loop has the same directionality as the IP helices (black arrow). The asterisks indicate the engineered cross-linking sites in the VV mutant of PIP4Kα. (C) Substrate specificity of the cross-linked PIP4Kα VV mutant (V217C/V377C). The inserted gel confirms the complete cross-linking of the VV mutant used in the assay. Assay of wild-type PIP4Kα, A371E, VV, and VV-A371E with PI(3)P, PI(4)P, and PI(5)P as substrates. Given the lower in vitro catalytic efficiency of PIP4Kα compared with PIP5Kα, unused radioactive ATP migrates below the PI(3,4)P2 spot.

All IPKs have a helical segment called the “IP helices” that folds over the inositol substrate from the side of the kinase that corresponds to the membrane binding surface of PIPKs (Fig. S7A). The helical segment is downstream of the β-strand that harbors the DxKxG sequence motif. The corresponding segment in PIPKs, the β8-α4c loop, is too short to play a similar role. The specificity loop of PIPKs, disordered in the crystal structures, is near the β8-α4c loop (Fig. S7B). Like the IP helices, the specificity loop harbors multiple positively charged residues, including a pair of highly conserved lysines. The N-terminal half of the loop is likely α-helical (19). To demonstrate that the specificity loop can fold back toward the β8-α4c loop to provide a similar side wall for the active site, we introduced two cysteines into a cysteine-less PIP4Kα: one within the β8-α4c loop and one within the specificity loop near the end of the predicted α-helix (Fig. S7B). The cysteines are readily cross-linkable by a disulfide bond, suggesting that their Cα atoms are less than 7.5 Å apart. Importantly, cross-linking did not hinder the ability of the loop to recognize the correct lipid substrate (Fig. S7C): the cross-linked kinase prefers PI(5)P over PI(4)P as its substrate, whereas the cross-linked A371E mutant, the opposite of the E382A mutation for PIP5Kα, lost its ability to phosphorylate PI(5)P but gained activity toward PI(4)P (28). The location of the specificity loop relative to other elements within the active site of the kinase makes it an ideal candidate to distinguish the orientation of the PIP substrate. It is interesting that some members of the IPK family, with simpler structures flanking the IP helices, can also phosphorylate lipid substrates (38).

Experimental Procedures

Protein Purification.

Mutants of PIP5Kα were generated from a construct containing residues 49–431 of zebrafish PIP5Kα (17) using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies). For crystallization, wild-type PIP5Kα was purified as described (17), with 1mM DTT added to the chromatography running buffer during the gel-filtration step. Only freshly prepared protein (25 mg/mL) was used to set up crystallization drops. For the radioactive kinase assay, protein preparations followed the same protocol without the final step of gel filtration. All purified proteins (from 0.25 mg/mL up to 2 mg/mL) were aliquoted, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, stored at −80 °C, and thawed on ice before assay. Wild-type human PIP4Kα was generated from a construct containing residues 33–406 of human PIP4Kα (pet28a). An His-tag and linker containing a thrombin cleavage site were cloned into the N terminus (MGSSHHHHHHSSGLVPRGSHM). To express this protein, BL21 de3 Gold cells were grown to an optical density of 0.600, protein expression was induced with 500 μM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG), and the cultures were left shaking overnight at room temperature. Pellet was resuspended in 25 mL of buffer [10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8)] per liter of culture and subjected to two freeze–thaw cycles. Lysozyme (25 mg per liter of culture), DNaseI (4 mg per liter of culture), and MgCl2 (200 μL of 1 M per liter of culture) were added to the resuspension, which was allowed to stir (30 min at room temperature). After a third freeze–thaw cycle, keeping the resuspension on ice, NaCl (1.5 g per liter of culture) was added to stir the resuspension (30 min at 4 °C). After spinning down the resuspension [19,500 rpm using a J-20 rotor (Beckman Coulter) for 1 h at 4 °C], the supernatant was incubated with cobalt resin (Talon Metal Affinity Resin; Clontech) for 1–4 h at 4 °C. Wash [20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8), 0.5M NaCl, 5 mM imidazole] and elution [20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8), 0.5 M NaCl, 200 mM imidazole] were performed at 4 °C, and aliquots were generated as stated above.

Crystal Structure Determination.

Crystallization sitting drops were set up at 4 °C in 0.1 M Mes monohydrate (pH 6.5) and 12% wt/vol polyethylene glycol 20,000. The crystallization trays were stored at 4 °C, and crystal growth occurred 3 d to 3 wk later. Soaking was accomplished in a stepwise manner, adding 100 mM sodium selenate, 100 mM pH-adjusted sodium phosphate, or 1 mM AMP-PNP with 2 mM MnCl2 to the crystallization solution. Cryoprotection was also accomplished stepwise, using 25% glycerol. The crystals were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen following the soaking steps. Diffraction data were collected at Beamline X29A at the National Synchrotron Light Source. Data were indexed and scaled using HKL2000 (39), refinement was conducted using CCP4i (40), and model building was performed using Coot (41).

SI Experimental Procedures

Radioactive Kinase Assay.

To prepare lipid substrate vesicles, PIPs (Echelon Biosciences) were resuspended in vesicle buffer (50 mM Tris at pH 8.0) at 1 mg/mL and sonicated in a water bath for 15 min. In 50 μL, PIPKs (5–50 ng for PIP5Ks and ∼1 μg for PIP4Ks) were incubated in kinase buffer [100 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4), 50 mM EGTA, and 100 mM MgCl2] with 20 μg of PIP vesicles, 10 μCi 32P-ATP, and 50 μM nonradioactive ATP for 15–25 min at room temperature. Reactions were terminated with 375 μL of chilled lipid extraction solution [chloroform, methanol, and HCl in a volume ratio of 3.3:3.7:0.1 with 10 μg/mL brain extract from bovine brain (type I; Folch Fraction I; Sigma Aldrich)] followed by 175 μL of PBS (Gibco, Life Technologies). Samples were vigorously vortexed for 30 s before centrifugation [2 min at 6,000 rpm (J-20 rotor; Beckman Coulter)]. The lower organic phase was collected, dried under vacuum, and solubilized in 40 μL of resuspension solution (chloroform and methanol in a volume ratio of 2:1). Analysis by TLC followed, using TLC silica gel plates (EMD Chemicals, Fisher Scientific) that had been heat-activated after soaking in treatment solution (1% potassium oxalate in methanol and water in a 1:1 volume ratio). TLC solvent phase (water, acetic acid, methanol, acetone, and chloroform in a 3:32:24:30:64 volume ratio) was used to separate the lipid species. The plates were allowed to run 1–3 h, with a longer run time giving better resolution of the spots, and signals were quantified by phosphorimaging (Bio-Rad Molecular Imager FX).

HPLC Analysis.

Samples of the radioactive kinase assay were dried as described above, deacylated (1 h at 50 °C) using methylamine (methylamine, water, l-butanol, and methanol in a volume ratio of 36:8:9:47), dried, thrice washed with water and dried, and resuspended (10 mM ammonium phosphate, pH 3.8). The head groups were extracted (l-butanol, petroleum ether, and ethyl formate in a volume ratio of 20:40:1) into the lower aqueous layer by vortexing, incubation (5 min at room temperature), and centrifugation [2 min at 10,000 rpm (J-20 rotor; Beckman Coulter)]. One more round of extraction on the organic phase was performed with water, and the combined aqueous layer was dried and resuspended (10 mM ammonium phosphate, pH 3.8). These deacylated samples, as well as internal standards, were filtered using Ultra-MC spin columns (Millipore) and then run on HPLC as described (42). Internal standards of PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,5)P2 were generated using p110γ PI3K (Sigma), which places a phosphate at the 3-position of PI(4)P or PI(5)P, in buffer [25 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM EGTA]. Deconvolution and curve fitting were accomplished using IGOR Pro by WaveMetrics.

ATPase Assay.

The ADP-Glo Kinase Assay was used (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s specifications at room temperature with 1 μg of purified protein in 25-μL sample reactions in a white 96-well plate. Luminescence readings from each sample were obtained with a SpectraMax M5 Multimode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices). Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Cell Culture, Viral Infection, and 3H Labeling.

HEK 293T cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 50 units/mL penicillin, and 50 mg/mL streptomycin sulfate. Zebrafish wild-type PIP5Kα and RxR/LD mutant were cloned into the pLPCX retroviral vector with a 3× Flag tag at the C terminus using in-fusion cloning reagents (Clontech). The expression plasmid, along with pMLV-Gag Pol plasmid and pVSV-G plasmid, were transfected into HEK 293T cells to produce PIP5Kα or RxR/LD retrovirus. A new batch of HEK 293T cells was infected by the retrovirus and selected with 1 mg/mL puromycin for 2 wk to obtain stable cell lines. Protein expression was confirmed by Western blot and immunofluorescence with Flag antibody (Cell Signaling). Cells were labeled for 3 d using 200 μCi per 10-cm plate of myo-[2-3H(N)]-inositol (Perkin-Elmer), lysed, and harvested; lipids were deacylated as described (43), and peaks were identified with the help of standards.

Western Blot.

Cells were washed with cold PBS and lysed with a buffer containing 20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100 in the presence of protease inhibitors. Total protein concentration was measured using the BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific). Typically 40 μg of total protein was used for SDS/PAGE, blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane, probed with Flag antibody and β-actin antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) at 4 °C overnight and detected with goat anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG (LI-COR) using an Odyssey CLx imaging system.

Immunofluorescence Staining.

Cells stably expressing wild-type or mutant PIP5Kα were seeded into six-well plates with coverslips. After 24 h, the cells were fixed with methanol for 15 min, twice washed with PBS, blocked and perforated with a PBS buffer containing 2.5% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100 for 1 h, and incubated with Flag antibody at 4 °C overnight. The cells were again washed twice with PBS, incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG (Alexa Fluor 488) for 2 h, and again washed twice with PBS before coverslips were mounted on slides using the Slow Fade Antifade Kit (Molecular Probes). Images were acquired with an inverted Nikon microscope (Eclipse TE2000-U) equipped with a CCD camera (MicroMAX RTE/CCD-1300Y).

PIKfyve Inhibition and Vacuole Formation.

Noninfected HEK 293T cells and infected cells stably expressing wild-type or mutant PIP5Kα were seeded into a six-well plate. After 24 h, cells were treated with various concentrations of YM-201636 for 2 h and examined by an Olympus phase-contrast microscope.

Acknowledgments

We thank Howard Robinson for assistance during X-ray diffraction data collection at Beamline X29A at the National Synchrotron Light Source. We thank Louise Lucast and Pietro De Camilli for help with HPLC, as well as Karen Anderson, David Calderwood, Anton Bennett, and Gary Rudnick for sharing their phosphorimager, fluorescent microscope, phase-contrast microscope, and imager. We also thank Benjamin Turk and Qianying Yuan for helpful discussions. This work was supported by Yale University (Y.H.), National Institutes of Health Grant GM112182 (to D.W. and Y.H.), and predoctoral fellowships from the Yale Gruber Foundation and the National Science Foundation (to Y.M.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 5E3S, 5E3T, and 5E3U).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1522112113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Di Paolo G, De Camilli P. Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature. 2006;443(7112):651–657. doi: 10.1038/nature05185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heck JN, et al. A conspicuous connection: Structure defines function for the phosphatidylinositol-phosphate kinase family. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;42(1):15–39. doi: 10.1080/10409230601162752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tolias KF, Cantley LC. Pathways for phosphoinositide synthesis. Chem Phys Lipids. 1999;98(1-2):69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(99)00019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van den Bout I, Divecha N. PIP5K-driven PtdIns(4,5)P2 synthesis: Regulation and cellular functions. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(Pt 21):3837–3850. doi: 10.1242/jcs.056127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shisheva A. PIKfyve: Partners, significance, debates and paradoxes. Cell Biol Int. 2008;32(6):591–604. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones DR, et al. Nuclear PtdIns5P as a transducer of stress signaling: An in vivo role for PIP4Kbeta. Mol Cell. 2006;23(5):685–695. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li S, et al. Mutations in PIP5K3 are associated with François-Neetens mouchetée fleck corneal dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77(1):54–63. doi: 10.1086/431346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Narkis G, et al. Lethal contractural syndrome type 3 (LCCS3) is caused by a mutation in PIP5K1C, which encodes PIPKI gamma of the phophatidylinsitol pathway. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):530–539. doi: 10.1086/520771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emerling BM, et al. Depletion of a putatively druggable class of phosphatidylinositol kinases inhibits growth of p53-null tumors. Cell. 2013;155(4):844–857. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun Y, et al. Type I gamma phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase modulates invasion and proliferation and its expression correlates with poor prognosis in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(1):R6. doi: 10.1186/bcr2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tolias KF, et al. Type I phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinases synthesize the novel lipids phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate and phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(29):18040–18046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X, et al. Phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase isozymes catalyze the synthesis of 3-phosphate-containing phosphatidylinositol signaling molecules. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(28):17756–17761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rameh LE, Tolias KF, Duckworth BC, Cantley LC. A new pathway for synthesis of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate. Nature. 1997;390(6656):192–196. doi: 10.1038/36621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McEwen RK, et al. Complementation analysis in PtdInsP kinase-deficient yeast mutants demonstrates that Schizosaccharomyces pombe and murine Fab1p homologues are phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate 5-kinases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(48):33905–33912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.33905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sbrissa D, Ikonomov OC, Shisheva A. PIKfyve, a mammalian ortholog of yeast Fab1p lipid kinase, synthesizes 5-phosphoinositides. Effect of insulin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(31):21589–21597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dove SK, et al. Osmotic stress activates phosphatidylinositol-3,5-bisphosphate synthesis. Nature. 1997;390(6656):187–192. doi: 10.1038/36613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu J, et al. Resolution of structure of PIP5K1A reveals molecular mechanism for its regulation by dimerization and disheveled. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8205. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao VD, Misra S, Boronenkov IV, Anderson RA, Hurley JH. Structure of type IIbeta phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase: A protein kinase fold flattened for interfacial phosphorylation. Cell. 1998;94(6):829–839. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81741-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kunz J, et al. The activation loop of phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinases determines signaling specificity. Mol Cell. 2000;5(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80398-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Endicott JA, Noble ME, Johnson LN. The structural basis for control of eukaryotic protein kinases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:587–613. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-052410-090317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rajakulendran T, Sahmi M, Lefrançois M, Sicheri F, Therrien M. A dimerization-dependent mechanism drives RAF catalytic activation. Nature. 2009;461(7263):542–545. doi: 10.1038/nature08314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng J, et al. 2.2 A refined crystal structure of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase complexed with MnATP and a peptide inhibitor. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1993;49(Pt 3):362–365. doi: 10.1107/S0907444993000423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams JA. Kinetic and catalytic mechanisms of protein kinases. Chem Rev. 2001;101(8):2271–2290. doi: 10.1021/cr000230w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Paolo G, et al. Impaired PtdIns(4,5)P2 synthesis in nerve terminals produces defects in synaptic vesicle trafficking. Nature. 2004;431(7007):415–422. doi: 10.1038/nature02896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Lian L, Golden JA, Morrisey EE, Abrams CS. PIP5KI gamma is required for cardiovascular and neuronal development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(28):11748–11753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700019104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Narkis G, et al. Lethal congenital contractural syndrome type 2 (LCCS2) is caused by a mutation in ERBB3 (Her3), a modulator of the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/Akt pathway. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):589–595. doi: 10.1086/520770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clarke JH, Irvine RF. Enzyme activity of the PIP4K2A gene product polymorphism that is implicated in schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2013;230(2):329–331. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3299-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kunz J, Fuelling A, Kolbe L, Anderson RA. Stereo-specific substrate recognition by phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinases is swapped by changing a single amino acid residue. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(7):5611–5619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110775200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker EH, Perisic O, Ried C, Stephens L, Williams RL. Structural insights into phosphoinositide 3-kinase catalysis and signalling. Nature. 1999;402(6759):313–320. doi: 10.1038/46319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wenk MR, et al. PIP kinase Igamma is the major PI(4,5)P(2) synthesizing enzyme at the synapse. Neuron. 2001;32(1):79–88. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown JR, Auger KR. Phylogenomics of phosphoinositide lipid kinases: Perspectives on the evolution of second messenger signaling and drug discovery. BMC Evol Biol. 2011;11:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.González B, et al. Structure of a human inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate 3-kinase: Substrate binding reveals why it is not a phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Mol Cell. 2004;15(5):689–701. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller GJ, Hurley JH. Crystal structure of the catalytic core of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate 3-kinase. Mol Cell. 2004;15(5):703–711. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grishin NV. Phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase: A link between protein kinase and glutathione synthase folds. J Mol Biol. 1999;291(2):239–247. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levdikov VM, et al. The structure of SAICAR synthase: An enzyme in the de novo pathway of purine nucleotide biosynthesis. Structure. 1998;6(3):363–376. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamaguchi H, Matsushita M, Nairn AC, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the atypical protein kinase domain of a TRP channel with phosphotransferase activity. Mol Cell. 2001;7(5):1047–1057. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00256-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang H, DeRose EF, London RE, Shears SB. IP6K structure and the molecular determinants of catalytic specificity in an inositol phosphate kinase family. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4178. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Resnick AC, et al. Inositol polyphosphate multikinase is a nuclear PI3-kinase with transcriptional regulatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(36):12783–12788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506184102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. In: Carter CW Jr, Sweet RM, editors. Methods in Enzymology. Vol 276. Academic; New York: 1997. pp. 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67(Pt 4):235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 4):486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakatsu F, et al. Sac2/INPP5F is an inositol 4-phosphatase that functions in the endocytic pathway. J Cell Biol. 2015;209(1):85–95. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201409064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakatsu F, et al. PtdIns4P synthesis by PI4KIIIα at the plasma membrane and its impact on plasma membrane identity. J Cell Biol. 2012;199(6):1003–1016. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201206095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]