Significance

It is still unclear why human beings hold higher intelligence than other animals on Earth and which brain properties might explain the differences. The recent studies have demonstrated that biophotons may play a key role in neural information processing and encoding and that biophotons may be involved in quantum brain mechanism; however, the importance of biophotons in relation to animal intelligence, including that of human beings, is not clear. Here, we have provided experimental evidence that glutamate-induced biophotonic activities and transmission in brain slices present a spectral redshift feature from animals (bullfrog, mouse, chicken, pig, and monkey) to humans, which may be a key biophysical basis for explaining why human beings hold higher intelligence than that of other animals.

Keywords: intelligence, ultraweak photon emissions, biophoton imaging, glutamate, brain slices

Abstract

Human beings hold higher intelligence than other animals on Earth; however, it is still unclear which brain properties might explain the underlying mechanisms. The brain is a major energy-consuming organ compared with other organs. Neural signal communications and information processing in neural circuits play an important role in the realization of various neural functions, whereas improvement in cognitive function is driven by the need for more effective communication that requires less energy. Combining the ultraweak biophoton imaging system (UBIS) with the biophoton spectral analysis device (BSAD), we found that glutamate-induced biophotonic activities and transmission in the brain, which has recently been demonstrated as a novel neural signal communication mechanism, present a spectral redshift from animals (in order of bullfrog, mouse, chicken, pig, and monkey) to humans, even up to a near-infrared wavelength (∼865 nm) in the human brain. This brain property may be a key biophysical basis for explaining high intelligence in humans because biophoton spectral redshift could be a more economical and effective measure of biophotonic signal communications and information processing in the human brain.

Despite remarkable advances in our understanding of brain functions, it is still unclear why human beings hold higher intelligence than other animals on Earth and which brain properties might explain the differences (1). Early studies have proposed that brain size and the degree of encephalization [encephalization quotient (EQ)] might be related to the evolution of animal intelligence, including that of human beings (2–4), but, so far, the relationship between relative brain size and intelligence is inconclusive, and EQ is also not the best predictor of intelligence (1, 5–7). Communications and information-processing capacity between neurons in neural circuits play an important role in the realization of various neural functions, such as sensorimotor control, learning and memory, consciousness, and cognition. The neural network studies have indicated that neural signal transmission and encoding is in a nonlinear network mechanism (8–10), in which biophotons, also called ultraweak photon emission (UPE), may be involved (11). A recent study has demonstrated that glutamate, the most abundant neurotransmitter in the brain, could induce biophotonic activities and transmission in neural circuits (12), suggesting that biophotons may play a key role in neural information processing and encoding and may be involved in quantum brain mechanism (11, 13–16); however, the importance of biophotons in relation to animal intelligence is not clear, in particular human high intelligence, such as problem-solving and analytical abilities. We hypothesized that the spectral redshift of biophotonic activities and transmission in the brain may play a key role. Here, we have provided experimental evidence that glutamate-induced biophotonic activities and transmission in brain slices present a spectral redshift feature from animals (bullfrog, mouse, chicken, pig, and monkey) to humans, which may be a key biophysical basis for explaining why human beings hold higher intelligence than that of other animals.

Results

Biophoton Spectral Imaging, Calibration, and Reference.

Because of the ultraweak intensity feature of biophotons, it is usually difficult to analyze biophoton spectral characteristics spatiotemporally, particularly in brain tissues. This paper introduces a method to resolve this problem, allowing analysis of the spectral characteristics of glutamate-induced biophotonic activities and transmission by combining the recently developed ultraweak biophoton imaging system (UBIS) (12) with a new biophoton spectral analysis device (BSAD).

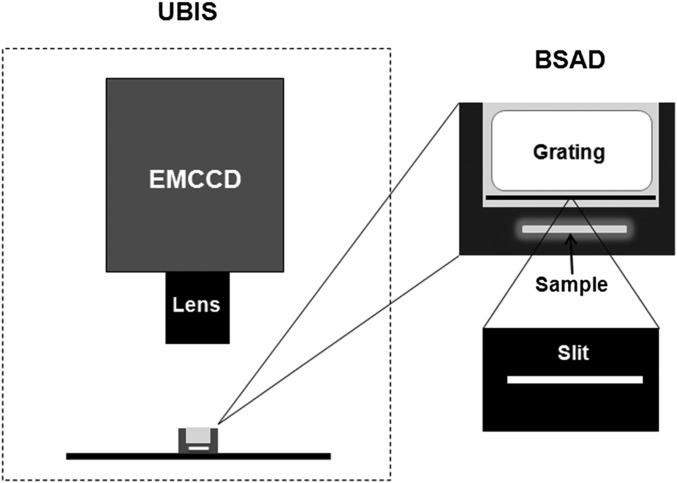

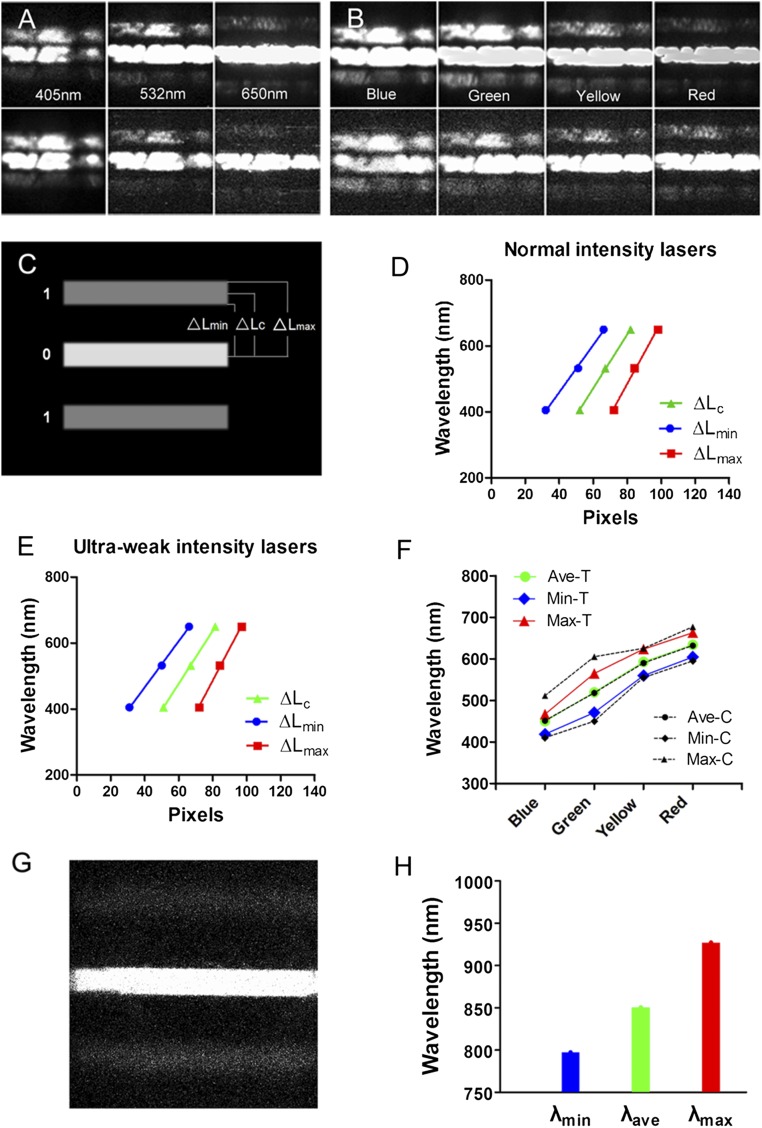

The BSAD consists of a slit and a transmission grating and is placed just above the sample during biophoton imaging such that the biophoton spectral images can be obtained with UBIS when biophotons pass a slit and then a grating (Fig. 1). First, it is necessary to determine the special spectral images for calibration and reference, and such images were captured with UBIS by applying various known-wavelength laser and light-emitting diode (LED) light sources for imaging. Under conditions of normal and ultraweak intensity laser and LED imaging, we obtained two types of photon spectral images: normal photon intensity spectral images (Fig. 2 A and B, Top) and ultraweak photon intensity spectral images (Fig. 2 A and B, Bottom). A light-reducing device was used to produce the ultraweak intensity photons from various laser and LED light sources, and the photon intensities were reduced to these levels (100–400 photons per square centimeter per second), similar to those of glutamate-induced biophotonic emissions in mouse brain slices (12).

Fig. 1.

Schematic drawing of the UBIS and BSAD. UBIS was described in detail in a previous report (12). BSAD consists of a slit (1 mm wide and 1 cm long) and a transmission grating (1,200 per millimeter) and is placed just above the sample during biophoton imaging. The right plane is an enlarged drawing of the BSAD in the left plane. The brain slice is incubated in a chamber containing perfusion solution (also see SI Methods).

Fig. 2.

Photon spectral images for calibration and reliability confirmation. (A and B) Photon spectral images were obtained from three wavelength lasers (405 nm, 532 nm, and 650 nm) (A) and four wavelength LED lights (blue, green, yellow, and red) (B) under conditions of normal intensities (up planes) and ultraweak intensities (down planes) (also see the detailed explanation in SI Methods), showing one zero-order fringe and two first-grade fringes. The two first-grade fringes present a trend away from the zero-order fringe from short to long wavelengths (blue to red). (C) Schematic drawing of a spectral image to analyze the relative central distance (△Lc), minimum (△Lmin), and maximum (△Lmax) edge distances from the first-grade fringe (digit 1) to the center of the zero-order fringe (digit 0) with an image analysis software (also see Fig. S1A ). (D and E) There are linear relations between the wavelengths and △Lc, △Lmin, or △Lmax in three lasers under the conditions of normal (D) and ultraweak (E) intensities. The linear regression coefficients (R2) are 0.9999, 0.9989, and 0.9978 for △Lc, △Lmin, and △Lmax, respectively, in D, and 0.9999, 0.9996, and 0.9990, respectively, in E; P = 0.005–0.042 (also see Table S1). (F) The relations between the calculated wavelengths (λave, λmin, and λmax) of four LED light sources (bigger color symbols) based on the spectral images under the conditions of ultraweak light intensities and the known pick and wavelength ranges [smaller black symbols; 451 nm (410–492 nm; blue), 518 nm (450–586 nm; green), 590 nm (555–625 nm; yellow), and 632 nm (595–669 nm; red)] measured with a spectrometer (also see Fig. S2). The calculated λave is almost same as the known pick wavelength of each LED light. (G) Representative biophoton spectral image obtained from a tree leaf (sweet-scented osmanthus tree), showing the clear zero-order fringe and two first-grade fringes (60-s imaging time). (H) The calculated wavelengths (λave, λmin, and λmax) from five leaves of this type of tree according to regression Eqs. 1–3.

A spectral image presents three clear bands (one zero-order fringe and two first-grade fringes) under the imaging condition of the present study based on the principle of grating imaging (Fig. 2 A and B). We analyzed the distribution of gray values (GVs) of zero-order and first-grade fringes in various laser spectral gray images (SI Methods) and defined the relative central distance (△Lc) and minimum (△Lmin) and maximum (△Lmax) edge distances from one of the two first-grade fringes to the center of the zero-order fringe (Fig. 2C and Fig. S1). We found that the laser wavelength (λ) is highly correlated to the △Lc, △Lmin, and △Lmax under conditions of normal and ultraweak light-intensity imaging (Fig. 2 D and E and Table S1). Therefore, a sample wavelength range can be calculated according to the △Lc, △Lmin, and △Lmax values of the sample and the following three linear regression equations (SI Methods):

| [1] |

| [2] |

| [3] |

where λave, λmin, and λmax are the average, minimum, and maximum wavelength, respectively, under the conditions of ultraweak photon intensity.

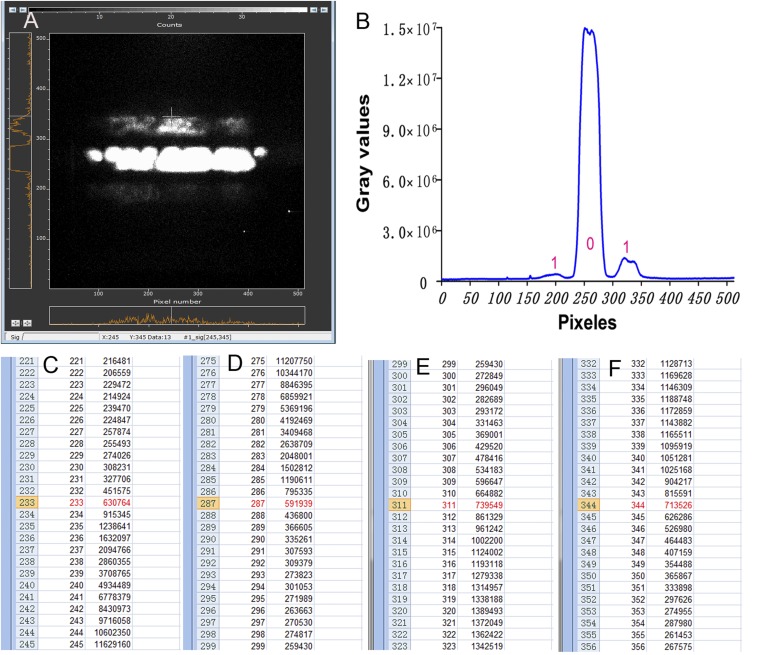

Fig. S1.

Photon spectral images for calibration and reliability confirmation. (A) Visual judgment of the spectral image with an image analysis software program (Andor Solis for Imaging Version 4.27.30001.0; Andor) for evaluating preliminarily the range of the edges; the “cross-sign” indicates the position of the far edge of one first-grade fringe. The position pixel values are shown at the bottom of the spectral image. (B) A representative distribution curve of the sum of GVs of a 1D matrix (512 pixels) parallel to the first-grade fringe (digit 1) and zero-order fringe (digit 0). (C–F) The sectioned range of numerical values of the sum of GVs near the two edges of the zero-order fringe (C and D) and first-grade fringe (E and F). The four numerical values (a–d) are marked by red color and are defined as the pixel number for calculating △Lc, △Lmin, and △Lmax. If, F0 = (a + b)/2 and F1 = (c + d)/2, then △Lc = F1 − F0, △Lmin = c − F0, and △Lmax = d – F0.

Table S1.

Correlation between spectra of lasers and △Lc, △Lmin, and △Lmax

| Spectra | △Lc, pixels | △Lmin, pixels | △Lmax, pixels |

| Spectra (n) | |||

| 405 nm | 52 | 32 | 72 |

| 532 nm | 67.5 | 51 | 84 |

| 650 nm | 82 | 66 | 98 |

| Correlation analysis | |||

| R2 | 0.9999 | 0.9989 | 0.9978 |

| P | 0.014 | 0.030 | 0.042 |

| Spectra (u) | |||

| 405 nm | 51.5 | 31 | 72 |

| 532 nm | 67 | 50 | 84 |

| 650 nm | 81.5 | 66 | 97 |

| Correlation analysis | |||

| R2 | 0.9999 | 0.9996 | 0.9990 |

| P | 0.005 | 0.018 | 0.028 |

n, under the conditions of normal light intensity; u, under the conditions of ultraweak light intensity.

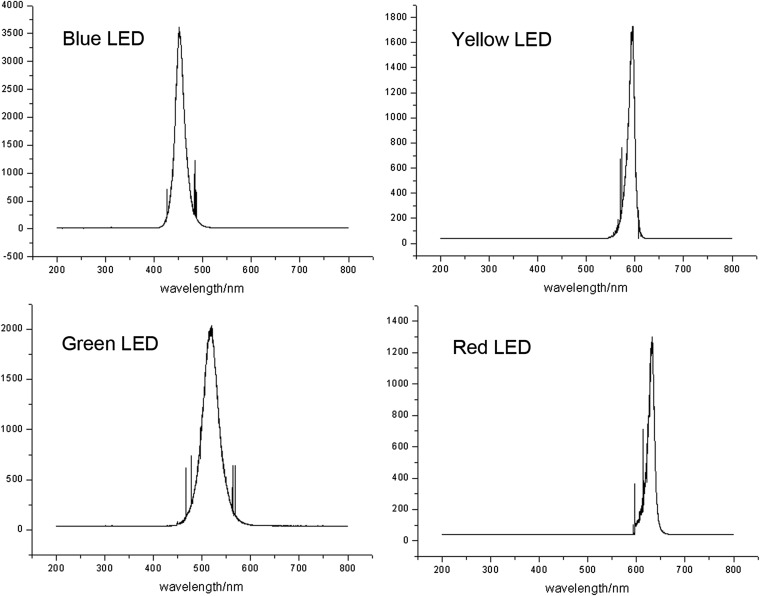

We have verified the reliability using data from various LED spectral images (Fig. 2B), and the results show that the calculated wavelength ranges (λave, λmin, and λmax) of four LED light sources according to the regression equations above and the measured values of △Lc, △Lmin, and △Lmax under the conditions of ultraweak light intensities are approximately equal to or within the known-wavelength ranges (Fig. 2F) measured by a spectrometer (Fig. S2).

Fig. S2.

The spectral curves of four LED lights. The spectra were obtained for each LED light source by a spectrometer. The start, pick, and stop wavelengths (nm) of blue (410, 451, and 492 nm), green (450, 518, and 586 nm), yellow (555, 590, and 625 nm), and red (595, 632, and 677 nm) are used to evaluate the references.

Then, we tested the emission spectra from a small piece of green leaves of sweet-scented osmanthus tree under the excitation condition of ambient light before imaging and found that they are 797 nm (λmin), 850 nm (λave), and 927 nm (λmax) (Fig. 2 G and H), indicating that the detected spectra belong to the range of the phosphorescence and fluorescence emission spectra attributable to photosynthesis (17, 18).

Glutamate-Induced Biophotonic Activities and Spectral Redshift from Animals to Humans.

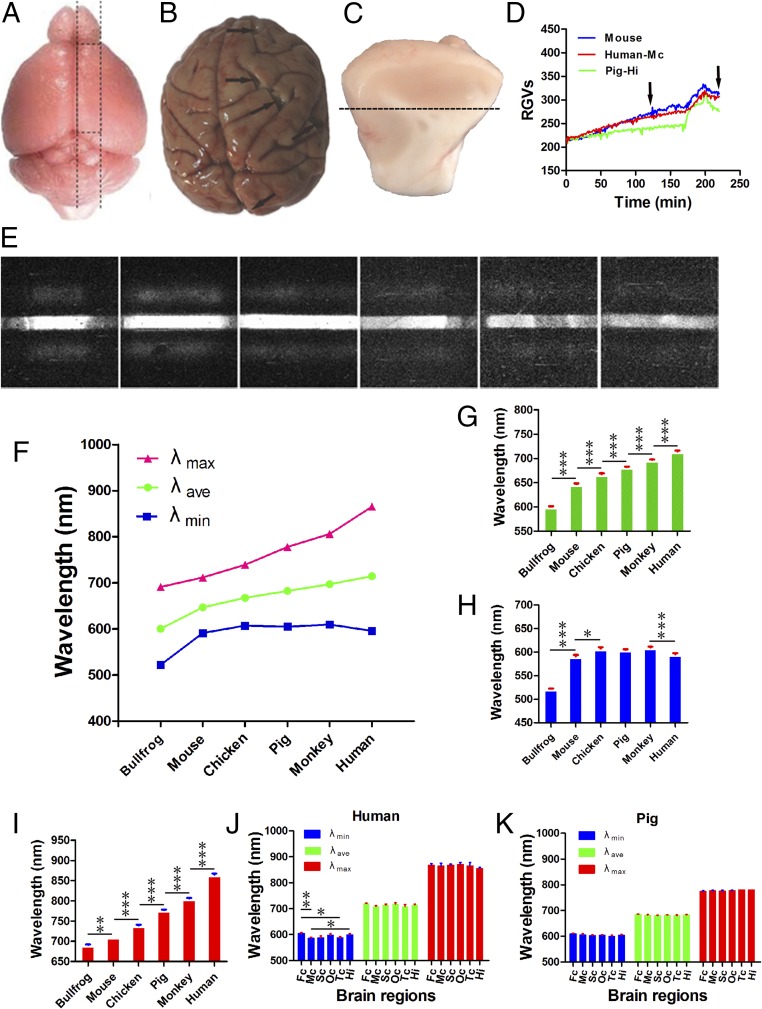

Biophotonic emissions in mouse brain slice present four typical periods or stages (initiation, maintenance, washing, and reapplication, respectively) after the application of 50 mM glutamate, and the origin of these stages is mainly attributable to the biophotonic activities and transmission along axons (12), suggesting that the analysis of the spectral characteristics of these biophotons may provide a new way to explore their importance in neural functions. In addition, the reasons for the application of such a concentration of glutamate to activate and maintain the biophotonic activities and transmission along neuronal axons or in neural circuits in mouse brain slices have been emphatically discussed in a previous study (12). In the present study, we investigated the spectral characteristics of glutamate-induced biophotonic emissions in bullfrog, mouse, chicken, pig, rhesus monkey, and human brain slices. The preparations of sagittal brain slices from bullfrogs, mice, and chickens and the particular brain slices from six different brain regions (five cortical areas and the hippocampus) in pigs, rhesus monkeys, and humans are detailed in Fig. 3 A–C and SI Methods. Seven postmortem human brains obtained from the Chinese Brain Bank Center (CBBC) were used for this study (Table S2). The recovery of neural cells from postmortem brain materials with suitable in vitro treatment is a key method to achieve glutamate-induced biophotonic emissions in human and pig brain slices, which is described specifically in SI Methods. Four typical stages of biophotonic emissions after the application of 50 mM glutamate to a mouse brain slice, a postmortem pig hippocampus slice, and a human motor cortical slice present a similar pattern, as shown in Fig. 3D. Biophoton spectral images were obtained by imaging biophotonic emissions across the maintenance, washing, and reapplication periods (Fig. 3D and SI Methods), and the first-grade fringe presents a trend away from the zero-order and becomes broader from bullfrog to human (in the order of bullfrog, mouse, chicken, pig, monkey, and human; Fig. 3E). A spectral redshift trend was significantly obvious for λave and λmax from animals to humans (Fig. 3 F–I), and the λmax is even up to a near-infrared wavelength (∼865 nm) in humans (Table 1). The individual differences of spectral values within the same species are very small, with nearly identical values in five bullfrogs, chickens, and mice. In addition, there were no significant differences in λave, λmin, or λmax between the different brain areas in the pig and human (Fig. 3 J and K and Table S3), with the exception of λmin between the certain areas (frontal cortex vs. motor cortex or temporal cortex, and motor cortex vs. hippocampus) in the human brain (Table S3). Although statistical analysis could not be carried out for the monkey because only three brains were tested due to strict restrictions of the number of rhesus monkeys for experimental research, the values of λave, λmin, or λmax obtained from different brain regions in three monkeys were nearly identical, suggesting that the conclusion from the pig might apply to the monkey.

Fig. 3.

Spectral redshift of glutamate-induced biophotonic emissions in brain slices presents an evolutional trend from animals to human. (A) Schematic drawing of the preparation of a particular sagittal brain slice (∼2 mm thickness) from a hemisphere of the mouse brain, which is identical in bullfrog and chicken brains. (B) The detailed regions of brain gyri dissected from primary occipital, motor, and sensory cortexes, the medial frontal cortex, and superior temporal cortex in a representative monkey brain (arrows), which are also similar in pig and human brains. (C) The preparation of a cortical slice (∼3 mm thickness) from a block of cortical gyrus of pig, monkey, and human; the dotted line indicates the cut position. This cortical slice contains all of the cortical layers and could ensure that the cut ends of the projection fibers originating from cortical neurons are directed toward the lens of the UBIS during imaging. (D) The representative dynamic change of biophotonic activities was demonstrated by relative GVs (RGVs) after the application of 50 mM glutamate in a mouse brain slice (blue curved line), a pig hippocampus slice (Pig-Hi) (green curved line), and a human motor cortical slice (human-Mc) [red curved line; CBBC no. 20160107; Table S2], presenting the four typical stages (initiation, maintenance, washing, and reapplication). These two human and pig brain slices were stored in modified ACSF (M-ACSF) at 0–4 °C for 12 and 24 h, respectively, before imaging. Real-time imaging is 120 min for regular biophoton images (an image every 1 min without BSAD) and 100 min for biophoton spectral images (an image every 25 min with BSAD) through the periods of maintenance (0–170 min), washing (171–195 min), and reapplication (196–220 min). The arrows indicate the start and stop time points for capturing biophoton spectral images. (E) Representative biophoton spectral images in animal and human brain slices. The first-order fringes present a trend away from the zero-order fringes in the order of bullfrog, mouse, chicken, pig, monkey, and human, indicating a spectral redshift from animals to humans. (F) Change trends of glutamate-induced biophoton spectral ranges (λave, λmin, or λmax) in the bullfrog, mouse, chicken, pig, monkey, and human. (G–I) Comparison of the spectral differences in λave (F = 399; P < 0.0001) (G), λmin (F = 82; P < 0.0001) (H), or λmax (F = 569; P < 0.0001) (I) in the bullfrog, mouse, chicken, pig, monkey, and human. (J and K) Comparison of the spectral differences in λave, λmin, or λmax in different brain regions in the pig (J) and human (K). Data show the means ± SEM. The number of brain slices in F–I: bullfrog (n = 5), mouse (n = 5), chicken (n = 5), pig (n = 34), monkey (n = 11), and human (n = 31). The number of brain slices in different brain regions (N): 6, 6, 5, 7, 4, and 6 for frontal cortex (Fc), motor cortex (Mc), sensory cortex (Sc), primary occipital cortex (Oc), temporal cortex (Tc), and hippocampus (Hi), respectively, in the pig and 6, 5, 4, 6, 3, and 7 for Fc, Mc, Sc, Oc, Tc, and Hi, respectively, in the human. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between the neighboring two groups in G–I: *P < 0.01; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.0001. Asterisks indicate a significant difference in different areas in J: Fc vs. Mc (**); Fc vs. Tc (*); Mc vs. Hi (*). *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01.

Table S2.

Clinical data of body donation subjects

| CBBC no. | Age, y | Sex | Bw, g | Pmd, h:min | Clinical diagnosis and cause of death |

| 20151207 | 62 | M | 1,150 | 4:00 | Respiratory and circulatory failure |

| 20151210 | 55 | F | 1,130 | 5:40 | Pulmonary heart disease, respiratory and circulatory failure |

| 20151227 | 54 | M | 1,541 | 9:00 | Respiratory and circulatory failure |

| 20151230 | 1.5 | M | 866 | 6:30 | Aromatic amino acid decarboxylase deficiency, multiple organ failure |

| 20160107 | 39 | M | 1,337 | 6:30 | Hydrocephalus and cerebral arteriosclerosis |

| 20160116 | 85 | M | 1,278 | 7:35 | Atherosclerosis, cardiac arrest, dementia |

| 20160117 | 47 | M | 1,331 | 7:00 | Dilated cardiomyopathy, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, schizophrenia, cardiac arrest |

Bw, brain weight; F, female; M, male; Pmd, postmortem delay.

Table 1.

Spectra in various species

| Species (N) | Spectra | ||

| λave, nm | λmin, nm | λmax, nm | |

| Bullfrog (5) | 600.3 ± 0.82 | 522.1 ± 0.74 | 691.2 ± 0.98 |

| Mouse (5) | 646.9 ± 1.53*** | 591.1 ± 2.78*** | 711.8 ± 0.0** |

| Chicken (5) | 667.3 ± 2.00*** | 607.4 ± 2.97* | 739.2 ± 1.96*** |

| Pig (34) | 682.3 ± 0.68*** | 604.9 ± 1.29 | 777.7 ± 0.75*** |

| Monkey (11) | 696.9 ± 0.85*** | 609.8 ± 1.76 | 806.1 ± 1.49*** |

| Human (31) | 714.6 ± 1.59*** | 595.6 ± 2.13*** | 865.3 ± 2.74*** |

| F value; P value | F = 399; P < 0.0001 | F = 82; P < 0.0001 | F = 569; P < 0.0001 |

λave, λmin, and λmax are the average, minimum, and maximum wavelength, respectively; N, the number of brain slices. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between the neighboring two groups: *P < 0.01; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.0001.

Table S3.

Spectra in different brain areas in pig and human

| BA (n, n) | Pig | Human | ||||

| λave, nm | λmin, nm | λmax, nm | λave, nm | λmin, nm | λmax, nm | |

| Fc (6, 6) | 684.9 ± 1.40 | 609.4 ± 3.13 | 775.4 ± 2.19 | 719.6 ± 2.11 | 604.4 ± 3.83 | 868.4 ± 5.06 |

| Mc (6, 5) | 682.1 ± 2.22 | 605.7 ± 4.46 | 777.0 ± 2.06 | 708.1 ± 4.16 | 586.6 ± 3.78 | 864.5 ± 11.00 |

| Sc (5, 4) | 680.4 ± 1.63 | 602.9 ± 2.78 | 776.4 ± 2.40 | 713.4 ± 3.91 | 587.7 ± 7.02 | 868.4 ± 4.00 |

| Oc (7, 6) | 682.2 ± 1.39 | 604.4 ± 2.29 | 777.5 ± 1.81 | 718.2 ± 4.43 | 598.2 ± 4.85 | 871.7 ± 6.02 |

| Tc (4, 3) | 680.8 ± 2.04 | 600.7 ± 3.71 | 780.3 ± 0.00 | 708.7 ± 7.20 | 587.1 ± 4.95 | 865.1 ± 13.05 |

| Hi (6, 7) | 682.8 ± 1.49 | 604.4 ± 2.71 | 780.3 ± 0.00 | 714.9 ± 2.43 | 600.2 ± 3.57 | 855.8 ± 3.52 |

| F value | 0.85 | 0.73 | 1.19 | 1.51 | 2.81† | 0.81 |

λave, λmin, and λmax are the average, minimum, and maximum wavelength, respectively. n is the number of slices in pig and human, respectively. A dagger (†) indicates a significant difference in different areas: Fc vs. Mc (**); Fc vs. Tc (*); Mc vs. Hi (*). *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. BA, Brain area; Fc, frontal cortex; Hi, hippocampus; Mc, motor cortex; Oc, primary occipital cortex; Sc, sensory cortex; Tc, temporal cortex.

Discussion

In the present study, the special prepared brain slices were allowed to analyze the spectra of glutamate-induced biophotons, which has been proven to be the active biophotons (12), but not the background biophotons that are generally believed to be a result of oxidative metabolism and oxidative stress (19–21) because the increase of biophotonic emissions by the application of glutamate is not correlated to the change in aerobic metabolism because the initiation and maintenance of glutamate-induced biophotonic emissions cannot completely blocked by cytochrome c oxidase inhibitor but could be significantly decreased by the application of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) inhibitor (okadaic acid potassium salt), which can induce the hyperphosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein tau and interferer with the function of microtubules (22).

The tendency of the spectral redshift of glutamate-induced biophotonic emissions in this study is in the order of frog, mouse, chicken, pig, monkey, and human, which is almost consistent with the phylogenetic tree. Although the present imaging technique could not distinguish and determine what types of neurons emit what types of spectral biophotons or whether a neuron or type of neurons emit different spectral biophotons, we indeed observed the evolutionary conservation in glutamate-induced biophotonic emissions in the near-blue spectra (λmin) from chicken to pig to monkey to human (Fig. 3 F and H).

There is no universally accepted definition of animal intelligence and no procedure to measure and compare the differences in different species; however, using mental and behavioral flexibility as a criterion for intelligence, it is generally accepted that, at least in problem-solving and language abilities rather than the specialized behaviors, to survive in their natural and social environments, human beings are assumed to be more intelligent than monkeys and that intelligence is decreasingly ordered as monkey > pig > (chicken and mouse) > bullfrog. Such a trend is consistent with our finding of a spectral redshift. Interestingly, we found that the chicken exhibits more redshift than the mouse, raising the question whether chickens hold higher cognitive abilities than those of mice. It has been suggested that birds might have evolved from a certain type of dinosaur (23) and that dinosaurs, which dominated on Earth for a long time, should hold certain advanced cognitive abilities over other animals. Based on this theory, it may be true that poultry have higher cognitive abilities than rodents, at least in language abilities, because certain birds, such as parrots, are able to imitate human words.

The neocortex in the brain is organized into columnar modules, which seem to be units of information processing (24), analogous to chips in a computer. The work of the brain involves neural information processing that is mainly transmitted along axons and dendrites, which are analogous to optic fibers. The neural information-processing capacity is an expensive adaptation for the economy of brain, and the improvement of cognitive functions such as language is driven by the need for more effective communication that requires less energy (25). We found obvious spectral redshift of glutamate-induced biophotonic emissions in the human brain cortex and hippocampus. Based on recent knowledge of the level of intelligence, which is related anatomically to the number of cortical neurons and physiologically to the speed of conductivity of neural pathways, the spectral redshift means that the human brain may use lower energy biophotons (longer spectra) to carry out neural signal communications between neurons to be more effective and economical.

It should be emphasized that despite the use of entangled photons has realized quantum teleportation (transmission) (26), however, it is still not clear how the brain carry out neural information transfer, coding and storage via biophotons. Recent experimental results have shown that biophotons may transmit along neural fibers and in neural circuits (12), and theoretical analyses have proposed that it is possible to realize the intensity and spectral coding and quantum computation via microtubules based on the physical features of biophotons (27, 28). In addition, although the biophotonic intensity is very weak, this may not affect them as a quantum information carrier because, according to the assumption and current experiential findings of the quantum teleportation (transmission), the change of quantum state would likely lead to information transfer if such a state is in quantum entanglement (26).

We hope that these findings can bring a new viewpoint to understand the mechanisms of brain information transmission and information processing and provide an explanation for why human brains are better than those of other animals in some advanced cognitive functions, such as language, planning, problem-solving, and analytical abilities.

Overall, if biophotonic activities and transmission dominate the information neural processing and encoding mechanism in the brain, then biophoton spectral redshift could improve and strengthen cognitive abilities, which may not only provide an important theoretical basis for understanding why human beings could hold such a high degree in our intelligence but also provide new ideas for the development of artificial intelligence products and models of a functioning brain.

Methods

This study was carried out under strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the NIH (29). The protocol was approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of South-Central University for Nationalities. Detailed information regarding materials and methods is described in SI Methods. Human brain materials were obtained from the CBBC by autopsy through the human body donation program, which is organized and implemented by the Wuhan Red Cross Society. According to the protocol of CBBC and the human body donation program, specific permission for brain autopsy and use of the brain material and medical records for research purposes were obtained either from the donors themselves or from relatives, and also approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of South-Central University for Nationalities. When a body donor was deceased, the donation program office at Wuhan Red Cross Society was first informed by either from doctors or from relatives usually by telephone. Then donation program coordinators would arrange the transport of donated body to an approved autopsy center, where the brain was carefully removed according to a standard procedure and collected by CBBC.

SI Methods

Bullfrog, Mouse, Chicken, Pig, Monkey, and Human Brain Materials.

Adult bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana) were obtained from a commercial supplier and kept in a tank in which they were permitted free access to a pool of running water, a dry platform, and food. Bullfrogs were pithed, and the brain was quickly removed and placed in ice-cold (0–4 °C) Ringer’s solution. Ringer’s solution contained (in mM) 111 NaCl, 1.6 MgCl2, 2.5 KCl, 1.0 CaCl2, 10 d-glucose, and 3 Hepes (pH 7.8).

Adult female chickens (1.5–1.8 kg) were obtained from a commercial supplier. Adult male Kunming mice (2–3 mo) were purchased from the Hubei Provincial Laboratory Animal Public Service Center (Wuhan, China) and housed in a room with a 12-h-light/12-h-dark cycle (lights on at 0700 hours) with access to food and water ad libitum. Chickens and mice were decapitated and the brain was quickly removed and placed in ice-cold (0–4 °C) artificial cerebral spinal fluid (ACSF). ACSF contained (in mM) 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 20 d-glucose (pH 7.4).

Seven pig brains were obtained from a slaughterhouse in Wuhan City, China. The pigs were killed through a standard procedure carried out by the slaughterhouse. The brains were removed from the skulls with an ∼1.5- to 3-h postmortem delay.

Three rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta; two females and one male), ages 4–6 y old, were obtained from the Huayu Breeding Base of the Rhesus Monkey in Nanyang City, Henan province, China. Specific permission for the use of rhesus monkeys for research purposes was approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of South-Central University for Nationalities. The monkeys were slightly anesthetized with a combined animal anesthetic and decapitated. The brains were quickly removed from the skulls. It should be emphasized that these three monkeys were allowed to be killed for research purposes because they were unable to feed because of fractures of the hands or legs but did not show any obvious brain damage.

Human brain materials were obtained from the CBBC by autopsy through the human body donation program, which is organized and implemented by the Wuhan Red Cross Society. According to the protocol of CBBC and the human body donation program, specific permission for brain autopsy and use of the brain material and medical records for research purposes were obtained either from the donors themselves or from relatives and were also approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of South-Central University for Nationalities. When a body donor was deceased, the donation program office at Wuhan Red Cross Society was first informed by either from doctors or from relatives usually by telephone. Then, donation program coordinators would arrange the transport of donated body to an approved autopsy center, where the brain was carefully removed according to a standard procedure and collected by CBBC. A total of seven postmortem human brains were collected for the present study (Table S2). The average age and postmortem delay were 49 y (1.5–85 y old) and 6 h:36 min.

Following removal of the brain from the skulls of pigs, monkeys, and humans, standardized pieces of gyrus from the medial frontal cortex, the primary occipital, motor and sensory cortexes, superior temporal cortex, and hippocampus were dissected. The detailed regions of dissected brain gyri in a representative monkey brain are indicated in Fig. 2B. The brain blocks were immediately placed into a container with modified ACSF (M-ACSF). M-ACSF contained (in mM) 252 sucrose, 3 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.4 NaH2PO4, and 10 d-glucose (pH 7.4) at 0–4 °C.

Preparation of Brain Slices.

For the preparation of a particular sagittal brain slice from a hemisphere of bullfrog, chicken or mouse brain, the whole brain was carefully separated into two hemispheres, and the sagittal brain slice (∼2 mm thickness) with the medial surface of the corpus callosum was prepared from one hemisphere with a vibratome (Fig. 2A).

For the pig, monkey, and human brain materials, the cortical gyrus blocks were cut into slices (∼3 mm thickness) containing all of the cortical layers (Fig. 2C), and the hippocampus was cut into coronal slices (∼3 mm thickness) containing the dentate gyrus, the C1–C4 regions, and part of the entorhinal cortex. The prepared brain slices were kept in M-ACSF at 0–4 °C for further experiments.

Recovery of Neural Cells from Postmortem Brain Materials.

With suitable in vitro treatment, the survival of human brain cells is possible even up to 10 h of postmortem delay (30). In addition, the successful culture of neuronal and glial cells and neural stem cells from postmortem human brain materials has been reported previously (31–33).

In the present study, we used previously reported methods to recover neural cells from postmortem pig and human brain materials. The prepared brain slices were incubated in M-ACSF at 0–4 °C for 1–2 h, and this treatment could recover glutamate-induced biophotonic emissions.

Preservation of Postmortem and Nonpostmortem Brain Slices.

Brain slices incubated with M-ACSF at 0–4 °C from postmortem human and pig brain materials or nonpostmortem monkey brain materials could preserve the tissue for a relatively long time, even up to 36 h, to the extent that biophotonic emissions can still be induced after the application of 50 mM glutamate.

In Vitro Biophoton Imaging System and Biophoton Imaging.

The in vitro UBIS was described in our recent study (12, 34). The prepared brain slices at 0–4 °C were transferred into a container with ACSF or Ringer’s solution at room temperature (∼23 °C) for a minimum of 1 h before imaging. Then, the brain slices were transferred to a chamber in which they were submerged in a perfusion bath of ACSF or Ringer’s solution (200 mL) that was contained in a glass bottle. A mixture of 95% O2 + 5% CO2 was constantly supplied with a membrane oxygenator placed in the ACSF or Ringer’s solution during the perfusion period. The perfusion was maintained through an input micropump and an output micropump (5 mL/min) outside the UBIS. The temperature (∼37 °C) of the medium in the perfusion chamber was maintained with an electrical heater. Biophotonic activities (emissions) were detected and imaged with the UBIS using an electron multiplier CCD camera (EM-CCD)(Andor) in water-cool mode (in this situation, the working temperature at the EM-CCD camera can be maintained as low as −95 °C) controlled by an image analysis software program (Andor Solis for Imaging Version 4.27.30001.0; Andor). The specific steps for biophoton detection and imaging were as follows: (i) the brain slices were transferred to a chamber in complete darkness for ∼30 min before imaging to exclude the effects of ambient light; (ii) real-time imaging was performed by automatically taking an image every 1 min for typical detection of glutamate-induced biophotonic emissions during four main periods or stages (initiation, maintenance, washing, and reapplication) after the application of 50 mM glutamate, and the imaging duration was 170 min for initiation and maintenance and 25 min for washing and reapplication; and (iii) a regular photograph of each brain slice was taken under the normal CCD model before and after the imaging processes were completed to locate the slice’s position under the imaging field of view.

Biophoton Spectral Imaging for Brain Slices.

Biophoton spectral images were obtained by combing the UBIS with a BSAD (Fig. 1B). The specific steps for obtaining biophotonic spectral images were as follows: (i) the BSAD was placed just above the perfusion chamber after regular biophoton imaging (an image every 1 min) for 120 min; (ii) the imaging focus was adjusted to the level of the slit; (iii) real-time imaging was performed by automatically taking an image every 25 min through the periods of maintenance (50 min), washing (25 min), and reapplication (25 min); and (iv) the last two spectral images were merged into an image for image processing, data extraction, and spectral analysis.

Calibration and Reference Spectral Imaging.

We applied various laser and LED light sources under the conditions of normal and ultraweak photon intensities to obtain calibration and reference spectral images, respectively. The light sources included violet (405 nm), green (532 nm), and red (650 nm) lasers, as well as blue (410–511 nm), green (450–605 nm), yellow (555–625 nm), and red (595–677 nm) LED lights. An optic fiber cable was used to conduct light sources into the UBIS for spectral imaging. The ultraweak intensity of various laser and LED lights were obtained with a light-reducing device to reach intensities similar to those of glutamate-induced biophotonic emissions in the mouse brain slices (100–400 photons per square centimeter per second). The specific steps for obtaining calibration and reference spectral images were as follows: (i) the BSAD was placed just on the top of one end of optic fiber; (ii) the imaging focus was adjusted at the level of a slit; and (iii) the spectral images were taken for various laser and LED light sources with an imaging time lasting for 30–60 s under the normal light intensities and 25 min under the ultraweak intensities. Five small pieces of green leaves of sweet-scented osmanthus tree under the excitation condition of ambient light before imaging were also used to obtain their phosphorescence and fluorescence emission spectral images as another reference.

Image Processing, Data Extraction, and Analysis.

The specific processes for image processing and data analysis were as follows: (i) all original gray images in TIF format were first processed with a program running on the MATLAB platform to eliminate the effect of cosmic rays (white spots) as described before (12, 34), resulting in the processed photon (or biophoton) gray images or photon (or biophoton) spectral gray images; (ii) the average GVs of the processed biophoton gray images were extracted in the area of the brain slice with an image analysis software program (Andor Solis for Imaging Version 4.27.30001.0; Andor), and the data were exported to Microsoft Excel for further analysis; (iii) the relative GVs were obtained at the different time points (four stages: initiation, maintenance, washing, and reapplication) according to a method described in a previous study (12); (iv) the GVs of each pixel from each processed photon (or biophoton) spectral gray image were extracted with same image analysis software program, and the data in 2D matrices (512 × 512 pixels for each image) were exported to Microsoft Excel for the further analysis of distribution of GVs in the zero-order fringe and the two first-grade fringes; and (v) the sum of GVs of a 1D matrix (512 pixels) parallel to the first-grade and zero-order fringes was obtained, and the distribution curve of the sum of GVs for each image can be plotted (Fig. S1B).

Definition of the Center and Edge of the First-Grade and Zero-Order Fringes.

The two edges of the zero-order fringe and one of the two first-grade fringes were defined for each spectral image by combining visual judgment of the spectral image with the image analysis software program mentioned above and the distribution of the sum of GVs. Visual judgment is quite useful to determine the range of an edge (Fig. S1A), and its detailed position (pixel number) can be then defined with the distribution of the sum of GVs according to the special change in the sum of GVs over the target range (Fig. S1B), which usually shows the biggest difference value between the two adjacent numerical values of the sum of GVs (Figs. S1 C–F). The smaller (or larger) numerical value is finally defined. If necessary, a pixel edge and ridge detection method focusing on the target range was also used based on a Sobel operator with a program running on the MATLAB platform when the definition is not quite clear with the methods mentioned above (34). The middle position of the two edges of a strip was defined as the center of the first-grade or zero-order fringe. The relatively distance (△L) from the center and the near and far edge of one of the two first-grade fringes to the center of the zero-order fringe were calculated and represented by pixel values. △L is set to three values including the relative central distance (△Lc) and minimum (△Lmin) and maximum (△Lmax) edge distances of the first-grade fringe to the center of the zero-order fringe (Fig. 2C).

Analysis and Calculation of Biophotonic Spectra.

We analyzed and calculated the biophotonic spectra of brain samples based on the △L values using lasers as calibration and LED lights as verification references.

The imaging characteristics of the transmission gratings can be described by the grating equation as follows:

| [S1] |

where d (1/1200 mm) is the distance between two grating slits (grating constant), θ is the angle of diffraction, k is a diffractive series, and λ is the wave length.

Here, only the zero-order fringe and first-grade fringe were considered; then K = 1. Therefore,

| [S2] |

Because

| [S3] |

where △L is the distance from the first-grade fringe to the zero-order fringe and S is the focal length of the lens (lens constant); then

| [S4] |

Because both d and S are constants, if

| [S5] |

then

| [S6] |

When the other conditions are consistent, the wavelength of light (λ) is linearly related to △L.

According to data obtained from our observations (Fig. 2 and Table S2), it was found that the wavelength of the laser (λ) is highly correlated to △Lc, △Lmin, and △Lmax under the conditions of normal (n) and ultraweak (u) light intensities, and therefore three regression equations for each condition were obtained as follows:

| [S7] |

| [S8] |

| [S9] |

| [S10] |

| [S11] |

| [S12] |

We have verified the reliability using data obtained from various LED light sources (also see Results), and, therefore, the biophoton wavelength can be calculated based on △Lc, △Lmin, and △Lmax values from samples and the regression equations (Eqs. S10–S12) under the ultraweak light intensities. The results were described as the average biophoton wavelength (λave), minimum biophoton wavelength (λmin), and maximum biophoton wavelength (λmax).

Statistical Analysis.

One-way ANOVA was used to compare the differences in biophoton wavelength (λave, λmin, and λmax) of brain slices among the various species and in different brain regions in the pig and human. Student–Newman–Keuls was used to compare the differences between species, as well as the differences between brain regions in pig and human brains. Student t test was also used to compare the differences between brain regions in pig and human brains.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 31070961, Sci-Tech Support Plan of Hubei Province Grant 2014BEC086, and the research team fund of the South-Central University for Nationalities (Grant XTZ15014).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. M.A.P. is a Guest Editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1604855113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Roth G, Dicke U. Evolution of the brain and intelligence. Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;9(5):250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jerison HJ. Animal intelligence as encephalization. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1985;308(1135):21–35. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1985.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrne R. The Thinking Ape: Evolutionary Origins of Intelligence. Oxford Univ Press; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibson KR. Evolution of human intelligence: The roles of brain size and mental construction. Brain Behav Evol. 2002;59(1-2):10–20. doi: 10.1159/000063730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouchard TJ., Jr Genes, evolution and intelligence. Behav Genet. 2014;44(6):549–577. doi: 10.1007/s10519-014-9646-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hofman MA. Evolution of the human brain: When bigger is better. Front Neuroanat. 2014;8:15. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dicke U, Roth G. Neuronal factors determining high intelligence. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2016;371(1685):20150180. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lefebvre J, Hutt A, Knebel JF, Whittingstall K, Murray MM. Stimulus statistics shape oscillations in nonlinear recurrent neural networks. J Neurosci. 2015;35(7):2895–2903. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3609-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teramae JN, Tsubo Y, Fukai T. Optimal spike-based communication in excitable networks with strong-sparse and weak-dense links. Sci Rep. 2012;2:485. doi: 10.1038/srep00485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gollisch T, Meister M. Rapid neural coding in the retina with relative spike latencies. Science. 2008;319(5866):1108–1111. doi: 10.1126/science.1149639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang R, Dai J. Biophoton signal transmission and processing in the brain. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2014;139:71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang R, Dai J. Spatiotemporal imaging of glutamate-induced biophotonic activities and transmission in neural circuits. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz JM, Stapp HP, Beauregard M. Quantum physics in neuroscience and psychology: A neurophysical model of mind-brain interaction. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360(1458):1309–1327. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plankar M, Brežan S, Jerman I. The principle of coherence in multi-level brain information processing. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2013;111(1):8–29. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koch C, Hepp K. Quantum mechanics in the brain. Nature. 2006;440(7084):611–612. doi: 10.1038/440611a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costa JN, Dotta BT, Persinge MA. Lagged coherence of photon emissions and spectral power densities between the cerebral hemispheres of human subjects during rest conditions: Phase shift and quantum possibilities. World J Neurosci. 2016;6(2):119–125. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ndao AS, et al. Analysis of chlorophyll fluorescence spectra in some tropical plants. J Fluoresc. 2005;15(2):123–129. doi: 10.1007/s10895-005-2519-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krasnovsky AA, Jr, Kovalev YV. Spectral and kinetic parameters of phosphorescence of triplet chlorophyll a in the photosynthetic apparatus of plants. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2014;79(4):349–361. doi: 10.1134/S000629791404004X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kataoka Y, et al. Activity-dependent neural tissue oxidation emits intrinsic ultraweak photons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;285(4):1007–1011. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakano M. Low-level chemiluminescence during lipid peroxidations and enzymatic reactions. J Biolumin Chemilumin. 1989;4(1):231–240. doi: 10.1002/bio.1170040133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cifra M, Pospíšil P. Ultra-weak photon emission from biological samples: Definition, mechanisms, properties, detection and applications. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2014;139:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arias C, Sharma N, Davies P, Shafit-Zagardo B. Okadaic acid induces early changes in microtubule-associated protein 2 and tau phosphorylation prior to neurodegeneration in cultured cortical neurons. J Neurochem. 1993;61(2):673–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb02172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brusatte SL, O’Connor JK, Jarvis ED. The origin and diversification of birds. Curr Biol. 2015;25(19):R888–R898. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mountcastle VB. The columnar organization of the neocortex. Brain. 1997;120(Pt 4):701–722. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.4.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Armstrong E. Brains, bodies and metabolism. Brain Behav Evol. 1990;36(2-3):166–176. doi: 10.1159/000115305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao Z, et al. Experimental demonstration of five-photon entanglement and open-destination teleportation. Nature. 2004;430(6995):54–58. doi: 10.1038/nature02643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayburov SN. Photonic communications in biological systems. Vestn Samar Gos Tekhn Univ Ser Fiz-Mat Nauki. 2011;2(23):260–265. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Craddock TJ, Friesen D, Mane J, Hameroff S, Tuszynski JA. The feasibility of coherent energy transfer in microtubules. J R Soc Interface. 2014;11(100):20140677. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2014.0677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Institutes of Health . Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th Ed Natl Acad Press; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dai J, Swaab DF, Buijs RM. Recovery of axonal transport in “dead neurons”. Lancet. 1998;351(9101):499–500. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78689-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palmer TD, et al. Cell culture. Progenitor cells from human brain after death. Nature. 2001;411(6833):42–43. doi: 10.1038/35075141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verwer RW, et al. Cells in human postmortem brain tissue slices remain alive for several weeks in culture. FASEB J. 2002;16(1):54–60. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0504com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verwer RW, Dubelaar EJ, Hermens WT, Swaab DF. Tissue cultures from adult human postmortem subcortical brain areas. J Cell Mol Med. 2002;6(3):429–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2002.tb00522.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Z, Dai J. Biophotons contribute to retinal dark noise. Neurosci Bull. 2016;32(3):246–252. doi: 10.1007/s12264-016-0029-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindeberg T. Edge detection and ridge detection with automatic scale selection. Int J Comput Vis. 1998;30(2):117–154. [Google Scholar]