Significance

Aberrant amino acid metabolism has been reported in Huntington’s disease (HD), but its molecular origins are unknown. We show here that the master regulator of amino acid homeostasis, activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), is dysfunctional in HD, reflecting oxidative stress generated by impaired cysteine biosynthesis and transport. Accordingly, antioxidant supplementation reverses the diminished ATF4 response to nutrient stress. We identify a molecular link between amino acid disposition and oxidative stress that underlies multiple degenerative processes in HD. This disruption may be relevant to cellular dysfunction in other neurodegenerative conditions involving oxidative stress. Agents that restore cysteine balance may provide therapeutic benefit.

Keywords: Huntington’s disease, cysteine, CSE, oxidative stress, ATF4

Abstract

Disturbances in amino acid metabolism, which have been observed in Huntington’s disease (HD), may account for the profound inanition of HD patients. HD is triggered by an expansion of polyglutamine repeats in the protein huntingtin (Htt), impacting diverse cellular processes, ranging from transcriptional regulation to cognitive and motor functions. We show here that the master regulator of amino acid homeostasis, activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), is dysfunctional in HD because of oxidative stress contributed by aberrant cysteine biosynthesis and transport. Consistent with these observations, antioxidant supplementation reverses the disordered ATF4 response to nutrient stress. Our findings establish a molecular link between amino acid disposition and oxidative stress leading to cytotoxicity. This signaling cascade may be relevant to other diseases involving redox imbalance and deficits in amino acid metabolism.

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a lethal autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disease caused by an expansion of glutamine repeats in the protein huntingtin (Htt) (1). Mutant huntingtin (mHtt) elicits toxicity by impacting diverse cellular processes ranging from transcriptional regulation to cognitive and motor functions (2–4). Although several pathways affected by mHtt have been extensively studied, exact mechanisms whereby mHtt disrupts cellular function in HD have been unclear.

Abnormalities in amino acid metabolism have been frequently reported in HD, which may explain the weight loss and inanition observed during disease progression (5–7). We reported a substantial depletion of cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), the primary biosynthetic enzyme for the amino acid cysteine, in HD (8). Depletion of CSE occurs due to the sequestration of SP1, the basal transcription factor for CSE leading to lowered cysteine levels and elevated oxidative stress (9–11). Increased levels of oxidative stress markers have been linked to disease progression in HD, in which the antioxidant defense pathways are compromised (12, 13). The CSE/cysteine deficiency appeared to be pathogenic because treatment with cysteine or its precursor N-acetylcysteine was beneficial (8). Cysteine is a semiessential amino acid with multifaceted cellular functions (14, 15). Cysteine is obtained from both, the diet and by endogenous production via the reverse transsulfuration pathway (16, 17). In addition to serving as a building block for protein synthesis, cysteine is a component of the major antioxidant glutathione and a substrate for the biosynthesis of the gasotransmitter hydrogen sulfide, which itself has substantial antioxidant efficacy (16, 17). Cysteine is also the precursor of sulfur-containing molecules such as taurine and lanthionine, which have cytoprotective functions. In addition to SP1, expression of CSE can also be regulated by the transcription factor, activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) under conditions of stress (18, 19).

ATF4 is the master regulator of amino acid metabolism and is activated by amino acid deprivation (18). Levels of amino acids are finely controlled in cells by a balance between their synthesis, uptake, and utilization. ATF4 regulates the expression and activity of several amino acid biosynthetic genes as well as their transporters to ensure a constant supply of amino acids and maintain metabolic homeostasis (18, 20). In the present study we demonstrate deficits in the ATF4 response to cysteine deficiency, which can explain the defective amino acid disposition, overall metabolic dysfunction, and inanition of HD patients.

Results

Regulation of CSE and Its Transcription Factor ATF4 by Cysteine Levels.

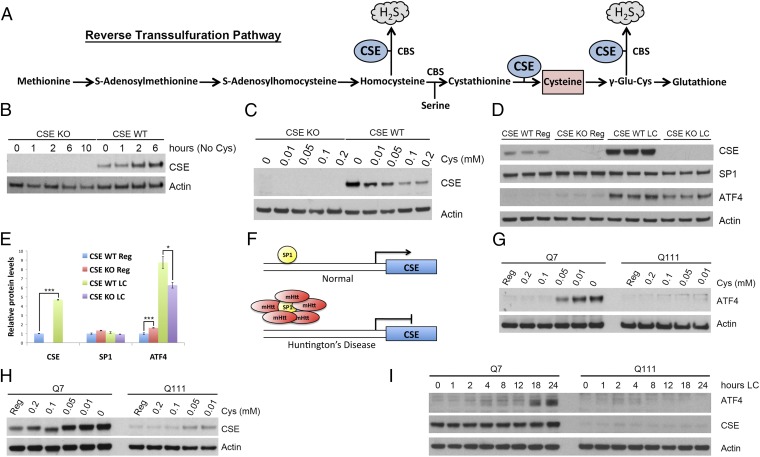

Earlier we reported a deficit of CSE in HD, which could account for neuropathologic and clinical features of the disease (8). We used the reverse transsulfuration pathway via which cysteine is generated as a readout to study ATF4 function in HD (Fig. 1A). Cysteine becomes essential when activity or expression of CSE is low. Thus, mice deleted for CSE lose weight on a cysteine-free diet (Fig. S1A) and die within 2 wk (21, 22) after undergoing massive muscle wastage and associated motor deficits as assessed by the rotarod assay (Fig. S1B). These abnormalities, reminiscent of several mouse models of HD, can be reversed by cysteine supplementation (Fig. S1B and Movie S1). In mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) deprivation of cysteine for as little as 1 h leads to increased CSE protein levels (Fig. 1B). To determine the cysteine concentration at which significant induction of CSE occurs without compromising cell viability, we cultured MEFs in media containing various cysteine levels (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1C). Reducing basal concentrations of cysteine from 0.2 mM (regular medium) to 0.05 mM doubles CSE levels, whereas in cysteine-free medium CSE levels are about six times the value in regular medium (Fig. 1C). We used a 0.05-mM cysteine (low cysteine, LC) concentration to reflect cysteine deficiency without eliciting major pathologic changes.

Fig. 1.

CSE is induced in response to cysteine deprivation and is regulated by ATF4. (A) Schematic representation of the reverse transsulfuration pathway leading to cysteine and glutathione biosynthesis. CSE uses cystathionine to generate cysteine, which in turn is used to produce hydrogen sulfide (H2S). (B) Kinetics of CSE induction in MEFs. MEFs derived from wild-type (WT) and CSE−/− (CSE KO) mice were incubated in cysteine-free medium, and induction of CSE was monitored at various time points by Western blotting using actin as a loading control. (C) CSE levels are inversely proportional to the cysteine content in the growth medium. MEFs were incubated with media containing varying concentrations of cysteine for 24 h and analyzed by Western blotting. (D) CSE and ATF4 are induced in response to low cysteine. Wild-type and CSE KO MEFs were grown in low-cysteine (LC) medium for 24 h. The levels of CSE, ATF4, SP1, and Actin (loading control) were monitored by Western blotting. (E) Quantitation of D. n = 3 (means ± SEM). *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001. (F) Schematic representation of SP1 sequestration by mHtt disrupting CSE expression in Huntington’s disease. (G) ATF4 is induced in response to cysteine depletion in Q7, but not in Q111, cells. Q7 and Q111 striatal cells were grown in medium containing different cysteine concentrations for 24 h, and ATF4 induction was monitored by Western blotting. (H) CSE is up-regulated under low-cysteine conditions in Q7, but not in Q111, striatal cells. Cell lysates used in G were used to monitor CSE induction. (I) Striatal Q7 and Q111 cells were grown in low cysteine (0.05 mM) for different time periods, and induction of CSE and ATF4 levels was monitored by Western blotting.

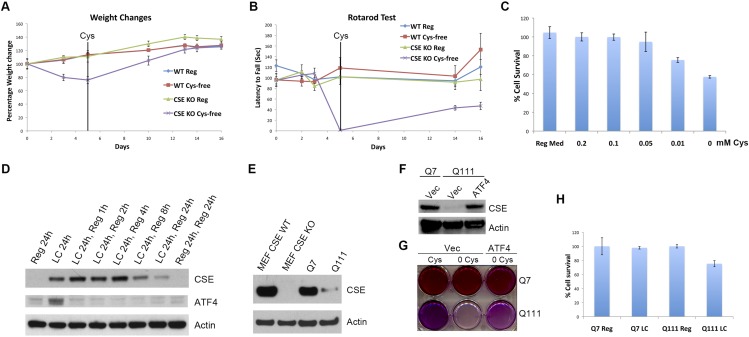

Fig. S1.

Cysteine becomes an essential amino acid in the absence of CSE. (A) CSE−/− (CSE KO) mice lose weight on a cysteine-free (Cys-free) diet. Wild-type (WT) and CSE KO mice were placed on a cysteine-free or regular (0.3% cysteine) diet starting 4 wk of age and weights were recorded. Cysteine was replenished at day 5 post deprivation and changes in weight measured. (B) CSE KO mice exhibited motor deficits on a cysteine-free diet. The motor functions of the wild-type (WT) and CSE KO mice used in A were assessed by the rotarod assay (Movie S1). (C) Cell proliferation of wild-type MEFs in media containing different concentrations of cysteine. Cells were incubated in medium containing varying concentrations of cysteine, and viability was assessed using the MTT assay. (D) ATF4 expression responds rapidly to cysteine concentrations. Wild-type MEFs were incubated in low-cysteine (LC) medium for 24 h. Cysteine was added back to the growth medium, and the levels of ATF4 and CSE were monitored by Western blotting at different time points. (E) CSE levels in striatal cells and MEFs. Q7 and Q111 striatal cells and wild-type (CSE WT) and CSE−/− (CSE KO) MEFs were harvested, and protein levels of CSE were assessed by Western blotting using actin as the loading control. (F) Overexpression of ATF4 rescues CSE expression. Q111 cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding ATF4. CSE levels were compared with that in Q7 cells by Western blotting using actin as a loading control. (G) Overexpression of ATF4 in striatal Q111 cells restores growth in cysteine-free medium. Striatal Q7 and Q111 cells were transfected with either the empty vector or that encoding ATF4, and growth in cysteine-free medium was monitored by MTT assay. Shown is a representative six-well plate showing enhanced growth of Q111 cells harboring ATF4 plasmid. (H) Striatal cell viability was not significantly affected by low cysteine medium growth. Striatal Q7 and Q111 cells were incubated in regular or low-cysteine medium for 24 h, and cell survival was assessed by MTT assay. Data are presented as means ± SE.

Under basal conditions SP1 is the principal transcription factor regulating levels of CSE, whereas in response to stress, especially with lowered amino acid levels, ATF4 is a major determinant of CSE expression. Induction of CSE and ATF4 occurs in response to cysteine deprivation with particularly striking influences upon ATF4 (Fig. 1D). For wild-type MEFs, levels of ATF4 are almost ninefold higher with low-cysteine medium than with regular medium, which is significantly greater than in CSE-deleted cells (Fig. 1 D and E). By contrast, SP1 levels are essentially the same in wild-type and CSE-deleted MEFs with either normal or low-cysteine concentrations (Fig. 1E). ATF4 expression is dynamically and rapidly regulated in response to cysteine (Fig. S1D). Thus, elevated levels of ATF4 elicited by low cysteine are restored to baseline values within 1 h of cysteine supplementation.

As HD is characterized by aberrant cysteine metabolism, with CSE as well as cysteine transporters altered alongside abnormalities in amino acid levels (8, 23, 24), we explored the regulation of ATF4 and its targets in a striatal cell culture model of HD harboring the expanded glutamine repeats characteristic of mHtt (25). In HD, basal CSE expression is diminished due to sequestration of SP1, the basal transcriptional activator for CSE, by mHtt (8) (Fig. 1F and Fig. S1E). This decrease observed in the HD striatal cells resembles that observed in CSE-depleted MEFs (Fig. S1E). High ATF4 levels, as occur in amino acid deprivation, induce CSE expression. Accordingly, overexpressing ATF4 in Q111 cells rescues CSE expression as well as growth in cysteine-free medium, consistent with a role for ATF4 in regulating CSE in striatal cells (Fig. S1 F and G). ATF4 levels are significantly augmented by cysteine depletion at 0.05 mM and progressively increase at lower cysteine concentrations in wild-type Q7 striatal cells, exhibiting a concentration–response relationship (Fig. 1G). However, in Q111 cells, low-cysteine concentrations fail to induce ATF4. The deficient ATF4 induction in Q111 cells is paralleled by a similar lack of CSE inducibility (Fig. 1H). The failure of Q111 cells to respond to low-cysteine levels is not an artifact of altered temporal regulation, as at multiple intervals from 1 to 24 h after low-cysteine exposure, ATF4 and CSE levels in Q111 cells remain negligible (Fig. 1I). ATF4 expression steadily increases with time in Q7 cells in 0.05 mM cysteine, whereas in Q111 cells, this increase is virtually absent (Fig. 1I). These alterations of CSE and ATF4 are not attributable to toxic sequelae of altered cysteine concentrations, as cell survival is not markedly different in Q7 and Q111 cells in regular medium and is only modestly decreased in Q111 cells maintained on low-cysteine medium (Fig. S1H).

Failure of ATF4 Induction Is Specific to Cysteine Deprivation.

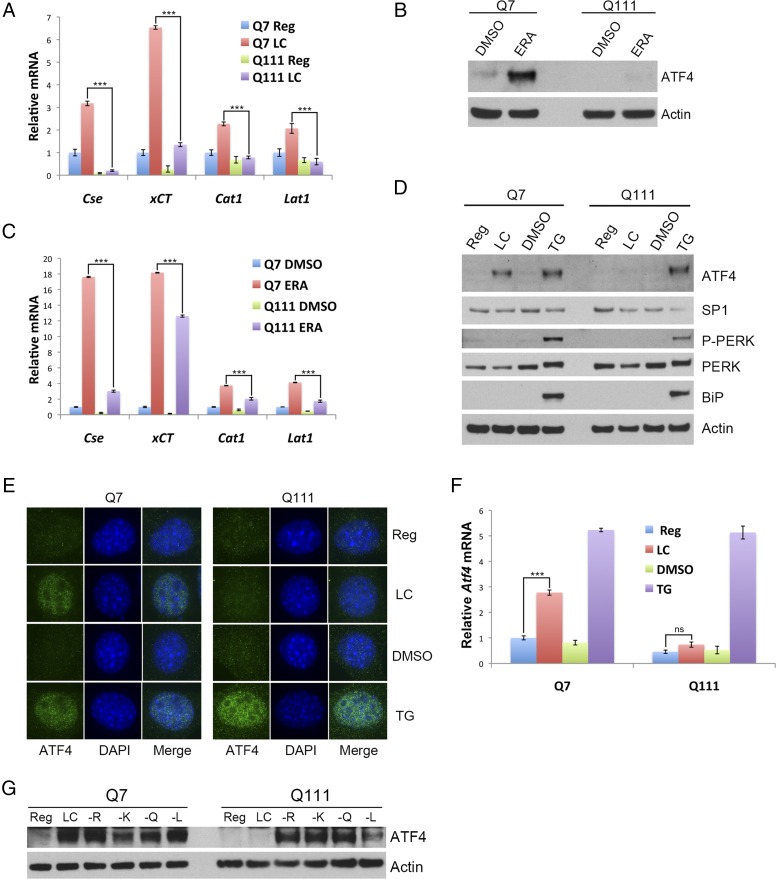

We monitored transcriptional targets of ATF4, such as the genes for xCT, the transporter for cystine; cationic amino acid transporter 1 (CAT1), a transporter for positively charged amino acids; and LAT1, a transporter for large amino acids. Similar to CSE, these genes exhibit a diminished response to cysteine deprivation in Q111 cells (Fig. 2A). As another means of eliciting cysteine deficiency, we treated cells with erastin, which blocks cystine import by inhibiting xCT (26). The induction of ATF4 by erastin in Q7 cells is lost in Q111 cells, confirming that the deficient response in HD due to lack of cysteine is linked to regulatory mechanisms for amino acid deprivation (Fig. 2B). Moreover, erastin treatment fails to activate transcription of the ATF4 targets, Cth (Cse), xCT, Cat1, and Lat1 significantly (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Lack of induction of ATF4 in striatal cells expressing mutant huntingtin is specific to cysteine deprivation. (A) Transcriptional targets of ATF4 are not induced in response to cysteine deprivation in Q111 cells. Striatal Q7 and Q111 cells were grown in regular or low-cysteine media, and transcript levels of Cse, xCT, Cat1, and Lat1, which encode CSE, cystine transporter, cationic amino acid transporter 1, and large amino acid transporter 1, respectively, were monitored by real-time qPCR. n = 4 (means ± SEM). ***P < 0.001. (B) Inhibition of cystine uptake also fails to induce ATF4 in Q111 cells. Striatal Q7 and Q111 cells were treated with 0.5 µM erastin (ERA), an inhibitor of xCT, the cystine transporter, to induce cysteine deprivation for 24 h. ATF4 was monitored by Western blotting. (C) Transcriptional targets of ATF4 were not induced in response to erastin treatment in Q111 cells. Striatal Q7 and Q111 cells were grown in regular medium and treated with 0.5 µM ERA. Transcript levels of Cse, xCT, Cat1, and Lat1 were monitored by real-time qPCR. n = 3 (means ± SEM). ***P < 0.001. (D) ATF4 is induced in response to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in both Q7 and Q111 cells. Striatal cells were incubated in regular or low-cysteine (LC) medium or in regular medium (Reg) containing DMSO (vehicle) or 1 µM thapsigargin (TG) for 24 h. ATF4 and SP1, the markers of ER stress (not induced in LC) phosphorylated PERK, the ER chaperone binding Ig protein (BiP), and actin (loading control) levels were monitored by Western blotting. (E) Immunofluorescence analysis depicting the up-regulation and nuclear localization of ATF4 in response to low cysteine and ER stress. Q7 and Q111 cells were incubated as in D and the cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for ATF4 (green) and DNA (DAPI). (Magnification, 60×.) (F) The up-regulation of ATF4 and CSE occurs at the transcriptional level. Striatal Q7 and Q111 cells were incubated as in D. Cells were scraped and the RNA was isolated and analyzed by real-time qPCR. n = 4 (means ± SEM). ***P < 0.001; ns: not significant. (G) ATF4 is induced in response to deprivation of other amino acids. Striatal cells were grown in media individually deprived of the amino acids arginine (−R), lysine (−K), glutamine (−Q), or leucine (−L) for 24 h. ATF4 induction was assessed by Western blotting.

Is the deficient response of ATF4 in Q111 cells specific to cysteine deprivation? We monitored the induction of ATF4 by other stress stimuli in striatal cells. We evaluated thapsigargin, a known inducer of ATF4, which elicits endoplasmic reticulum stress by depleting intracellular calcium stores. Thapsigargin markedly induces ATF4 to a similar extent in Q7 and Q111 cells in addition to the ER stress markers, phosphorylated PERK, and binding Ig protein BiP (Fig. 2D). The subcellular localization of the transcription factor ATF4 was also monitored. Immunofluorescence analysis reveals selective concentration of ATF4 in nuclei with no notable differences in Q7 and Q111 cells in response to thapsigargin and in Q7 cells in response to low cysteine. No induction of ATF4 is observed in Q111 cells under low cysteine (Fig. 2E). The deficient response of Q111 cells to low cysteine occurs at the transcriptional level as Atf4 mRNA fails to increase in Q111 cells cultured in low cysteine (Fig. 2F). The disrupted ATF4 response is unique to cysteine deprivation as in Q111 cells induction of ATF4 by arginine, lysine, glutamine, and leucine deprivation appears normal (Fig. 2G).

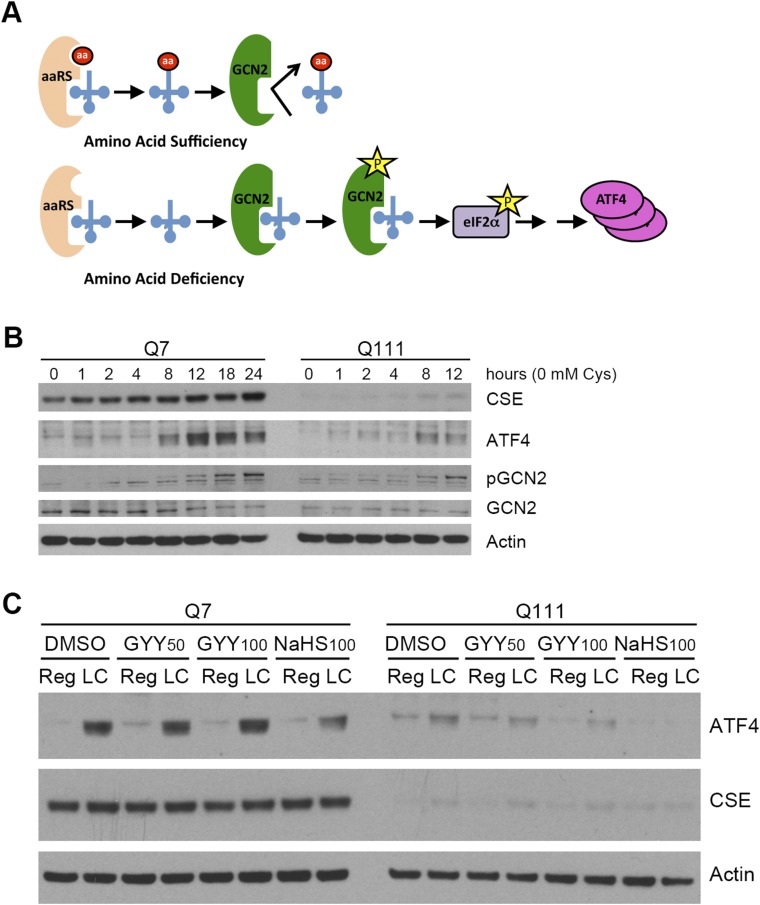

We wondered whether the deficient ATF4 response in HD might stem from abnormalities in amino acid sensing, a process that is reflected by levels of phosphoGCN2 (20) that serve as a marker for amino acid deprivation (Fig. S2A). Cysteine deprivation elicits a similar augmentation of phosphoGCN2 in Q111 as in Q7 cells, indicating that amino acid sensing is intact in HD (Fig. S2B). As cysteine is metabolized by CSE to H2S, the diminution of which in HD might be pathogenic, we considered whether a decrease in H2S might be responsible for the aberrant ATF4 induction. However, the H2S donors, GYY4137 and NaHS, fail to rescue the deficient ATF4 responses to low cysteine in Q111 cells (Fig. S2C).

Fig. S2.

Amino acid sensing and H2S involvement in HD. (A) Schematic representation of the sensing of amino acid deprivation by the general control nonderepressible2 kinase (GCN2). When amino acid levels are sufficient, charging of tRNAs by the aminoacyl tRNA synthetase (aaRS) occurs. When cells are starved for any amino acid, its cognate tRNA remains uncharged and binds to GCN2, the amino acid sensor, inducing its autophosphorylation. Activated GCN2 phosphorylates the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) and inhibits its activity, leading to a global translational arrest. Under these conditions, translation of a few select mRNAs such as the ATF4 mRNA occurs, which orchestrates the response of cell survival pathways. (B) Amino acid deprivation sensing is not affected in Q111 cells. Q7 and Q111 striatal cells were incubated in medium deprived of cysteine for different time periods. CSE, ATF4, phosphorylated GCN2, and total GCN2 were monitored by Western blotting with actin as a loading control. (C) H2S does not restore ATF4 induction. Q7 and Q111 cells were incubated with DMSO (vehicle) or the H2S donors GYY4137 (50 and 100 µM) and NaHS (100 µM) in low- or regular-cysteine media. ATF4 and CSE were monitored by Western blotting.

Low Cysteine Promotes Oxidative Stress in HD.

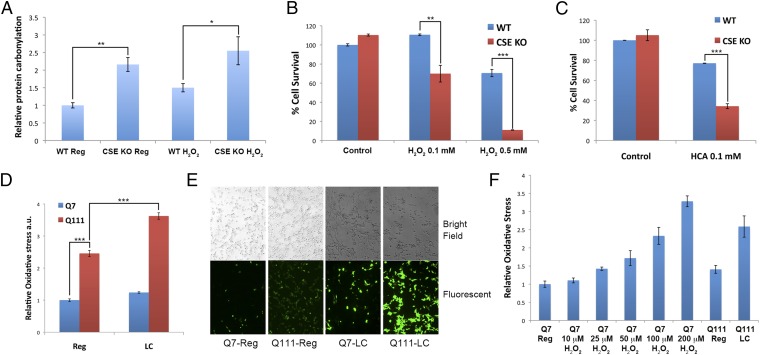

What distinguishes cysteine from other amino acids? Cysteine is unique among amino acids in displaying antioxidant properties so that its depletion might elicit oxidative stress. MEFs from CSE knockout cells display a doubling of basal protein carbonylation as well as enhanced sensitivity to the oxidant H2O2 (Fig. 3A). Moreover, toxic effects of H2O2 and homocysteic acid, an oxidant and analog of glutamate, are increased in neurons of CSE-deleted mice (Fig. 3 B and C). The depletion of CSE in HD cells appears to influence oxidative stress responses, as oxidative stress is doubled in Q111 cells in normal medium and increased 3.5-fold in cells on low cysteine (Fig. 3D). Microscopic examination reveals augmented reactive oxygen species (ROS) throughout the cells of Q111 preparations compared with Q7 cells, which is accentuated in response to cysteine deprivation. (Fig. 3E). We compared the extent of oxidative stress elicited by H2O2 in Q7 cells and Q111 cells cultured in low cysteine (Fig. 3F). Stress levels in Q111 cells are almost doubled by low cysteine, reaching levels similar to that generated by 100 µM H2O2 in Q7 cells.

Fig. 3.

Elevated ROS is the causative factor for diminished ATF4 response in Q111 striatal cells. (A) CSE−/− (CSE KO) MEFs exhibit elevated oxidative stress. Wild-type (WT) and CSE KO MEFs were incubated in regular medium or in regular medium containing 100 µM H2O2 for 24 h. Oxidation was assessed by measuring protein carbonylation. n = 3 (means ± SEM). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. (B) Primary cortical neurons from CSE KO mice are more vulnerable to oxidative stress. Primary cortical neurons from wild-type or CSE KO mice were incubated in medium with or without H2O2 for 18 h. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay. n = 3 (means ± SEM). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (C) Primary cortical neurons from CSE KO mice are more susceptible to the oxidant homocysteic acid (HCA). Primary cortical neurons from wild-type or CSE KO mice were treated with or without HCA for 18 h. Cell viability was assessed by MTT assay. n = 3 (means ± SEM). ***P < 0.001. (D) Striatal Q111 cells have elevated reactive oxygen species. Striatal Q7 and Q111 cells were grown in regular or low-cysteine medium for 24 h. Cells were treated with the fluorescent indicator CellROX green to assay levels of ROS. n = 3 (means ± SEM). ***P < 0.001. (E) Striatal Q7 and Q111 cells were grown in low-cysteine (LC) medium for 24 h and incubated with the redox-sensitive fluorescent indicator CM-H2DCFDA and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. (Magnification, 10×.) (F) Relative oxidative stress in striatal Q7 and Q111 cells. Q7 cells were incubated with different concentrations of H2O2 for 24 h and compared with Q111 cells incubated in regular or low-cysteine medium for 24 h. Oxidative stress was measured as in D. n = 3 (means ± SEM).

Antioxidant Supplementation Restores the ATF4 Response to Cysteine Deprivation.

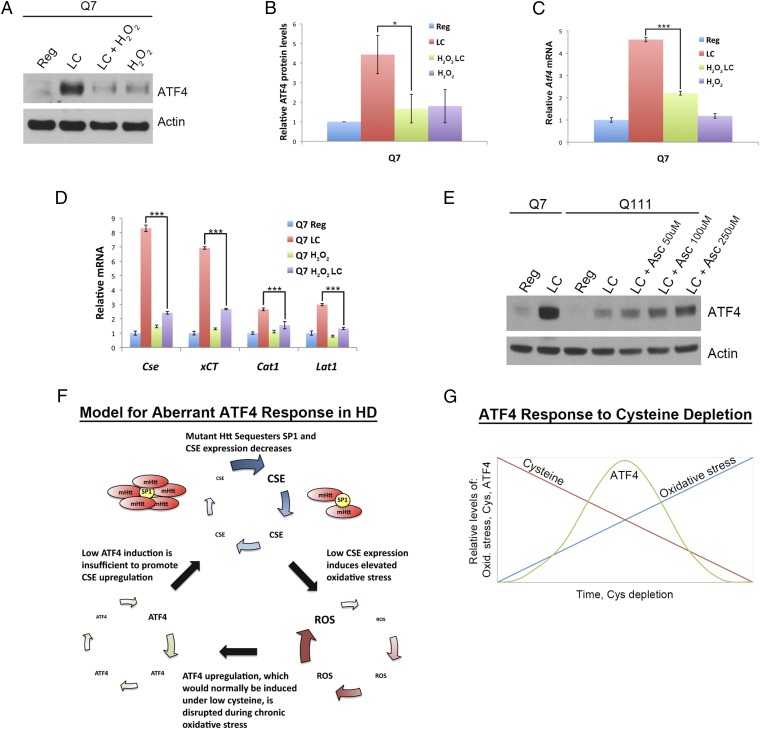

If oxidative stress underlies the abnormal response to low cysteine in HD, then these aberrations might be mimicked by treating normal cells with oxidants. We incubated Q7 cells with 100 µM H2O2 to induce oxidative stress equivalent to that observed in Q111 cells under low cysteine. Oxidative stress appears to blunt induction of ATF4 by low cysteine. In Q7 cells low cysteine elicits increased ATF4 levels, whereas this increase is diminished in cells exposed to low cysteine in the presence of H2O2 (Fig. 4 A and B). Responses of Atf4 mRNA are similar to the increases elicited in protein levels with low cysteine quadrupling Atf4 mRNA levels in Q7 cells, whereas H2O2 substantially diminishes this response (Fig. 4C). Similarly, target genes for ATF4, such as Cse, xCT, Cat1, and Lat1, are up-regulated by low cysteine, an effect prevented by H2O2 treatment (Fig. 4D). The importance of redox balance in regulating the ATF4 inducibility during low-cysteine conditions is evident in experiments using the antioxidant ascorbate (Fig. 4E). In a concentration-dependent fashion, ascorbate increases the diminished ATF4 levels of Q111 cells. Thus, elevated oxidative stress in Q111 cells appears to be responsible for the lack of induction of ATF4 in HD (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Diminished ATF4 induction caused by oxidative stress is reversed by antioxidant supplementation. (A) Oxidative stress suppresses ATF4 response to cysteine deprivation in Q7 cells. Q7 striatal cells were grown in regular and low-cysteine (LC) medium with or without 100 µM H2O2 for 24 h. ATF4 levels were monitored by Western blotting using actin as a control. (B) Quantitation of A. n = 4 (means ± SEM). *P < 0.05. (C) Q7 striatal cells were treated as in A and harvested, and Atf4 mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time qPCR. n = 3 (means ± SEM). ***P < 0.001. (D) Transcriptional targets of ATF4 are diminished in wild-type striatal Q7 cells under oxidative stress. Striatal Q7 cells were treated with 100 µM H2O2 to induce oxidative stress and grown in low-cysteine medium, and targets of ATF4, Cse, xCT, Cat1, and Lat1 were analyzed at the transcript level. n = 3 (means ± SEM). ***P < 0.001. The induction of these transcripts was decreased under oxidative stress in Q7 cells. (E) Reducing oxidative stress by antioxidant supplementation rescues ATF4 response to cysteine deprivation. Striatal Q7 and Q111 cells were incubated in regular or low-cysteine medium for 24 h. Q111 cells were also grown in low-cysteine medium containing different concentrations of ascorbate for 24 h, and ATF4 levels were monitored by Western blotting. (F) Model for aberrant ATF4 response in HD. Schematic representation of the model for lack of ATF4 response in HD. Early in the disease, levels of CSE, the biosynthetic enzyme for cysteine, an amino acid with major antioxidant properties, are normal. With disease progression, CSE levels decrease due to sequestration of SP1, the basal transcription factor for CSE, by mHtt. Low levels of CSE and low levels of cysteine transporters observed in HD result in decreased cysteine levels in cells and consequent oxidative stress. The progressive increase in oxidative stress elicited by cysteine deficit would normally be ameliorated by induction and activity of the transcription factor ATF4. Under these stress conditions, ATF4 regulates CSE and other target genes. However, chronic oxidative imbalance, such as that in HD, disrupts the up-regulation of ATF4 in response to stress. Poor induction of ATF4 thus results in further elevation of oxidative stress, which leads to a further inhibition of ATF4 up-regulation and disruption of amino acid homeostasis. This vicious cycle culminates in reduced viability of cells. (G) Schematic representation of diminished ATF4 response as a function of oxidative stress caused by cysteine deprivation. When cysteine is depleted, ATF4 is induced (depicted by green line). In addition, cysteine deprivation (red line) also results in increased oxidative stress (blue line). The induction of ATF4, which is optimal during low-grade oxidative stress, starts declining with greater accumulation of reactive oxygen species, suggesting a “threshold” beyond which ATF4 induction is compromised.

Discussion

The principal finding of our study is that disordered amino acid homeostasis in HD reflects dysfunctions of the transcription factor ATF4, a master regulator of amino acid disposition. The perturbation stems from the oxidative stress generated by cysteine deficits associated with the disease. In addition to depletion of CSE, the biosynthetic enzyme for cysteine, levels of two cysteine/cystine transporters, the excitatory amino acid transporter 3 (EAAT3/EAAC1), and the solute carrier family 7, member 11 (SLC7A11/xCT), are also diminished in HD (23, 24). ATF4 regulates transcription of SLC7A11/xCT as well as CSE. These findings may reflect a vicious cycle in HD, which commences with the sequestration of SP1 by mHtt. This leads to decreased CSE expression, depressed levels of cysteine, and diminished antioxidant defenses. As cysteine has antioxidant properties and is a component of the major antioxidant glutathione, depletion of cysteine augments oxidative stress. Low levels of oxidative stress physiologically enhance ATF4 and CSE expression, responses that are disrupted during the chronic oxidative stress of HD. Lack of CSE induction leads to further oxidative stress that, in turn, further exacerbates redox imbalance. This cycle thereby maintains diminished CSE along with heightened oxidative stress and blunted ATF4 response (Fig. 4F). Thus, oxidative stress within a physiological range can be mitigated by the ATF4 pathway. However, when the oxidative stress persists or exceeds a certain level, restorative responses of ATF4 decline. Thus, our results suggest a threshold for oxidative stress beyond which induction of ATF4 is diminished (Fig. 4G).

ATF4 is a prominent regulator for diverse aspects of amino acid disposition, which include metabolism of cysteine and branched chain amino acids (18). Depletion of branched chain amino acids has been implicated in muscle shrinkage observed in HD (5). Similarly, a pathogenic role for cysteine deficiency in HD is supported by the beneficial effects of N-acetylcysteine (8, 27) and couples with evidence for cysteine disturbances in other conditions of oxidative stress including aging, neurodegeneration, AIDS, and insulin resistance syndrome (28–32). Disturbances of cysteine disposition in multiple diseases may reflect a form of “cysteine stress” with widespread impact. Thus, stimulating the reverse transsulfuration pathway offers therapeutic avenues for mitigating symptoms associated with diseases involving oxidative stress.

Materials and Methods

Materials and reagents used as well as details of experimental procedures are available in SI Materials and Methods and Table S1. All animals were treated in compliance with the recommendations of the National Institutes of Health and approved by The Johns Hopkins University Committee on Animal Care.

Table S1.

Probes used in qPCR assays

| Gene | Taqman gene expression assay ID |

| Actb/Actin | Mm02619580_g1 (ThermoFisher Scientific) |

| Creb2/Atf4 | Mm00515325_g1 (ThermoFisher Scientific) |

| Cth/Cse | Mm00461247_m1 (ThermoFisher Scientific) |

| Slc7a11/xCT | Mm00442530_m1 (ThermoFisher Scientific) |

| Slc7a1/Cat1 | Mm01219063_m1 (ThermoFisher Scientific) |

| Slc7a5/Lat1 | Mm00441516_m1 (ThermoFisher Scientific) |

SI Materials and Methods

Cell Lines.

The striatal progenitor cell line STHdhQ7/Q7, expressing wild-type huntingtin, and STHdhQ111/Q111, expressing mutant huntingtin harboring 111 glutamine repeats (referred to as Q7 and Q111 cells, respectively), were from M. MacDonald (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA). The CSE−/− MEFs were generated from CSE−/− mice and immortalized using SV40T antigen.

Chemicals.

Unless otherwise mentioned, all chemicals were from Sigma. Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was used for all transfection studies.

Western Blotting.

Cells were lysed on ice for 15 min in buffer composed of 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitors, followed by centrifugation and recovery of the supernatant. Protein concentrations were estimated with the bicinchoninic acid assay (Thermo Scientific). Anti-CSE antibodies were described previously (33). Anti-ATF4 antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technologies or Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-BiP, GCN2, PERK, and phospho-PERK antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-SP1 and actin-HRP antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti–phospho-GCN2 antibodies were from Abcam.

RNA Isolation and RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from cells and tissues using TRIzol reagent followed by the RNEasy Lipid Tissue kit (Qiagen). Conventional RT-PCR was performed with the SuperScript One-Step RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen). Real-time qPCR was performed with the TaqMan RNA-to-Ct One-Step Kit and the Step One Plus instrument (Life Technologies). The qPCR probes are listed in Table S1.

Indirect Immunofluorescence Microscopy.

Striatal cells were cultured on coverslips, transfected, and processed as previously described (34).

Protein Assays.

Protein oxidation was assessed as a function of protein carbonylation using the OxyBlot Protein Oxidation Detection Kit (Millipore) that uses 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) to derivatize oxidize proteins, which can be detected by anti-DNPH antibody. Cells were lysed and 5 μg of protein was used in the reaction, followed by Western blotting.

Cell Viability Assays.

Cells were treated according to the experimental protocol and incubated for the designated times, and cell viability was calculated using 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT). MTT was added to cell cultures at 125 μg/mL for 60 min. The media was removed and cells were lysed in dimethyl sulfoxide, using an empty well as a blank. Absorbance was read at 570 nm, using 630 nm as the reference for cell debris.

Detection of ROS.

ROS were visualized using CM-H2DCFDA or CellRox Green reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Animals and Treatments.

Animals were housed on a 12-h light–dark schedule and received food and water ad libitum. The CSE−/− mice were previously described (33) and backcrossed for 11 generations on a C57BL6J background. All animals were treated in compliance with the recommendations of the National Institutes of Health and approved by the Johns Hopkins University Committee on Animal Care.

Cysteine Deprivation Studies in Mice.

All wild-type and CSE−/− mice offspring were placed either on an AIN93 mineral diet with 0.3% cystine or on an AIN93 diet containing no cystine (Teklad Lab Animal Diets; Harlan Laboratories) starting at 4 wk of age. For the rescue experiments, mice deprived of cysteine were placed back on the regular diet after cystine deprivation. Survival and motor phenotypes of the mice were recorded.

Motor Tests.

The accelerating rotarod was performed on a Rotamex V (Columbus Instruments) with speeds that varied from 4 to 40 rpm for a maximum of 5 min with an acceleration interval of 30 s.

Statistical Analysis.

Results are presented as means ± SEM for at least three independent experiments. The sample sizes used were based on the magnitude of changes and consistency expected. Statistical significance was reported as appropriate. In experiments involving animals, no exclusions were done. Sample sizes were chosen on the basis of the magnitude of changes expected. In behavioral analyses, the experimenter conducting the test was blinded to the genotype or treatment of the animals under study. P values were calculated with Student’s t test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Adele Snowman, Lynda Hester, and Lauren Albacarys for technical assistance. This work was supported by US Public Health Service Grant MH18501 (to S.H.S.) and by a grant from the CHDI Foundation (to S.H.S. and B.D.P.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1608264113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.The Huntington’s Disease Collaborative Research Group A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington’s disease chromosomes. Cell. 1993;72(6):971–983. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90585-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies SW, et al. Formation of neuronal intranuclear inclusions underlies the neurological dysfunction in mice transgenic for the HD mutation. Cell. 1997;90(3):537–548. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80513-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sugars KL, Rubinsztein DC. Transcriptional abnormalities in Huntington disease. Trends Genet. 2003;19(5):233–238. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00074-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhai W, Jeong H, Cui L, Krainc D, Tjian R. In vitro analysis of huntingtin-mediated transcriptional repression reveals multiple transcription factor targets. Cell. 2005;123(7):1241–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mochel F, Benaich S, Rabier D, Durr A. Validation of plasma branched chain amino acids as biomarkers in Huntington disease. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(2):265–267. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perry TL, Diamond S, Hansen S, Stedman D. Plasma-aminoacid levels in Huntington’s chorea. Lancet. 1969;1(7599):806–808. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)92068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phillipson OT, Bird ED. Plasma glucose, non-esterified fatty acids and amino acids in Huntington’s chorea. Clin Sci Mol Med. 1977;52(3):311–318. doi: 10.1042/cs0520311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paul BD, et al. Cystathionine γ-lyase deficiency mediates neurodegeneration in Huntington’s disease. Nature. 2014;509(7498):96–100. doi: 10.1038/nature13136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunah AW, et al. Sp1 and TAFII130 transcriptional activity disrupted in early Huntington’s disease. Science. 2002;296(5576):2238–2243. doi: 10.1126/science.1072613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishii I, et al. Murine cystathionine gamma-lyase: Complete cDNA and genomic sequences, promoter activity, tissue distribution and developmental expression. Biochem J. 2004;381(Pt 1):113–123. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang G, Pei Y, Teng H, Cao Q, Wang R. Specificity protein-1 as a critical regulator of human cystathionine gamma-lyase in smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(30):26450–26460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.266643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Browne SE, Beal MF. Oxidative damage in Huntington’s disease pathogenesis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8(11-12):2061–2073. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayala-Peña S. Role of oxidative DNA damage in mitochondrial dysfunction and Huntington’s disease pathogenesis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;62:102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pohlandt F. Cystine: A semi-essential amino acid in the newborn infant. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1974;63(6):801–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1974.tb04866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sturman JA, Gaull G, Raiha NC. Absence of cystathionase in human fetal liver: Is cystine essential? Science. 1970;169(3940):74–76. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3940.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paul BD, Snyder SH. H2S signalling through protein sulfhydration and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(8):499–507. doi: 10.1038/nrm3391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paul BD, Snyder SH. H2S: A Novel gasotransmitter that signals by sulfhydration. Trends Biochem Sci. 2015;40(11):687–700. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harding HP, et al. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol Cell. 2003;11(3):619–633. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickhout JG, et al. Integrated stress response modulates cellular redox state via induction of cystathionine γ-lyase: Cross-talk between integrated stress response and thiol metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(10):7603–7614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.304576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kilberg MS, Shan J, Su N. ATF4-dependent transcription mediates signaling of amino acid limitation. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20(9):436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mani S, Yang G, Wang R. A critical life-supporting role for cystathionine γ-lyase in the absence of dietary cysteine supply. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50(10):1280–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishii I, et al. Cystathionine gamma-lyase-deficient mice require dietary cysteine to protect against acute lethal myopathy and oxidative injury. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(34):26358–26368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.147439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X, et al. Aberrant Rab11-dependent trafficking of the neuronal glutamate transporter EAAC1 causes oxidative stress and cell death in Huntington’s disease. J Neurosci. 2010;30(13):4552–4561. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5865-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frederick NM, et al. Dysregulation of system xc(-) expression induced by mutant huntingtin in a striatal neuronal cell line and in R6/2 mice. Neurochem Int. 2014;76:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trettel F, et al. Dominant phenotypes produced by the HD mutation in STHdh(Q111) striatal cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9(19):2799–2809. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.19.2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dixon SJ, et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149(5):1060–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wright DJ, et al. N-acetylcysteine improves mitochondrial function and ameliorates behavioral deficits in the R6/1 mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e492. doi: 10.1038/tp.2014.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hildebrandt W, Kinscherf R, Hauer K, Holm E, Dröge W. Plasma cystine concentration and redox state in aging and physical exercise. Mech Ageing Dev. 2002;123(9):1269–1281. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(02)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hack V, et al. Cystine levels, cystine flux, and protein catabolism in cancer cachexia, HIV/SIV infection, and senescence. FASEB J. 1997;11(1):84–92. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.1.9034170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dröge W. Cysteine and glutathione deficiency in AIDS patients: A rationale for the treatment with N-acetyl-cysteine. Pharmacology. 1993;46(2):61–65. doi: 10.1159/000139029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carter RN, Morton NM. Cysteine and hydrogen sulfide in the regulation of metabolism: Insights from genetics and pharmacology. J Pathol. 2016;238(2):321–332. doi: 10.1002/path.4659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han Y, et al. Abnormal transsulfuration metabolism and reduced antioxidant capacity in Chinese children with autism spectrum disorders. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2015;46:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang G, et al. H2S as a physiologic vasorelaxant: Hypertension in mice with deletion of cystathionine gamma-lyase. Science. 2008;322(5901):587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1162667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sbodio JI, Paul BD, Machamer CE, Snyder SH. Golgi protein ACBD3 mediates neurotoxicity associated with Huntington’s disease. Cell Reports. 2013;4(5):890–897. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.