Abstract

Aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) and cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) are rare cerebrovascular pathologies. Here, we report the extremely rare coincidental presentation of both entities and discuss the likely relationship in aetiology and their optimal management. A female patient presented with headache and progressive neurological deficits. Cranial computed tomography and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) revealed dural venous sinus thrombosis, left-sided frontal and parietal infarcts, and left middle and anterior cerebral artery stenosis. In addition, left hemispheric subarachnoid haemosiderosis was seen on MRI. Following standard anticoagulation therapy for CVT, she represented with acute SAH. Digital subtraction angiography revealed a ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm and left middle cerebral artery/anterior cerebral artery vasospasms that were responsive to intra-arterial nimodipine. The latter were already present on the previous MRI, and had most likely prevented the detection of the aneurysm initially. The aneurysm was successfully coil embolised, and the patient improved clinically. Despite this case being an extremely rare coincidence, a ruptured aneurysm should be excluded in the presence of CVT and non-sulcal SAH. A careful consideration of treatment of both pathologies is required, since anticoagulation may have a potentially negative impact on aneurysmal bleeding.

Keywords: Aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage, cerebral vasospasm, cerebral venous thrombosis

Introduction

Both cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) and aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) are entities that may cause serious complications. A coincidence of these entities is extremely rare. It requires a careful therapeutic approach, as both entities and their specific therapy may potentially have a negative impact on each other.

We report the case of acute coincidental presentation of both entities with CVT, most likely following SAH from aneurysmal rupture. In addition, we discuss the likely relationship in aetiology and management of both entities.

Case report

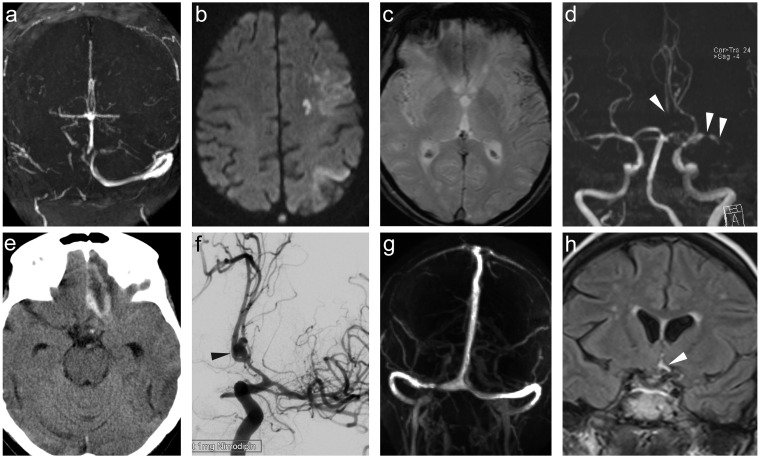

A 63-year-old woman presented with a three-week history of headache, with recent progression, disorientation, reduced consciousness and aphasia. She had a medical history of smoking, arterial hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Computed tomography (CT) and subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed dural venous sinus thrombosis involving the superior sagittal and right lateral dural sinus (Figure 1(a)), and left frontal and parietal cortical infarcts (Figure 1(b)). Further, in MRI, left hemispheric subarachnoid haemosiderosis (Figure 1(c)) and, in magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), high-grade left middle cerebral artery (MCA) and bilateral anterior cerebral artery (ACA) stenoses were disclosed (Figure 1(d)). On contrast-enhanced T1w images, an anterior communicating artery (AcomA) aneurysm was only suspected in the presence of impaired image quality related to movement artefacts, but could not be confirmed on other sequences. At this stage, haemosiderosis, vasospasms and infarcts were interpreted as being secondary to CVT. Screening for other prothrombotic conditions was negative. The patient was heparinised with subsequent oral anticoagulation after a control-CT scan, which ruled out complications.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows superior sagittal and right lateral sinus thrombosis (2D time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography (2D TOF MRA), (a)), left frontal and parietal cortical infarcts (diffusion weighted imaging (DWI), (b)), and left hemispheric subarachnoid haemosiderosis (GRE image, (c)). 3D TOF MRA discloses high-grade left middle cerebral artery (MCA) and anteriori cerebral artery (ACA) stenosis (arrowheads in (d)). Computed tomography shows acute subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) in the left frontobasal region (e). Digital subtraction angiography reveals ruptured AcomA aneurysm and improved MCA and ACA vasospasm following intra-arterial nimodipine application (arrowhead in (f)). Progressive recanalisation of cerebral venous thrombosis is found on follow-up MR venogram (2D TOF MRA, (g)). Minimal subacute SAH in AcomA region is demonstrated on FLAIR image of the initial MRI examination (arrowhead in (h)).

Five weeks later, she presented again with acute severe headache. CT with CT angiography (CTA), as well as a subsequent digital subtraction angiography (DSA), demonstrated acute SAH due to a ruptured AcomA aneurysm and vasospasms in the left MCA/ACA territories (Figure 1(e) and (f)). Successful coil embolisation and spasmolytic therapy with intra-arterial nimodipine were performed. In addition, partial recanalization of CVT was seen in the DSA. Anticoagulation was changed to aspirin. The patient showed clinical improvement. A follow-up MRI after six months disclosed complete aneurysm occlusion and progressive recanalization of CVT (Figure 1(g)).

Discussion

Non-traumatic SAH is caused by the rupture of a cerebral aneurysm in 85% of cases. Still, aneurysmal rupture has an incidence of approximately 10/100,000 persons per year.1 The annual incidence of CVT is estimated to approximately 3–4/1,000,000 persons.2

To our knowledge, there is only one single report of coincidental aneurysmal SAH and CVT, in which cortical venous thrombosis followed aneurysmal rupture and later deteriorated into a fatal thrombosis of major dural sinuses.3 Rarely, non-aneurysmal, sulcal SAH occurs in CVT.4 In these cases, SAH is found relative to localised venous hypertension with secondary rupture of cortical veins.

In our case, CVT was diagnosed first and treated with the standard therapy of anticoagulation. The presence of SAH and infarcts was initially misinterpreted as being related to CVT. Later, the ruptured aneurysm was discovered at its likely second rupture. In retrospect, the distribution of left-hemispheric haemosiderosis, which also involved the basal cisterns, and the left MCA territory infarcts, corresponding to vasospasm on the initial MRI, are both more likely caused by SAH from initially undisclosed aneurysm rupture rather than by CVT. This hypothesis is further supported by the presence of minimal subacute blood in the AcomA region on initial MRI, which was discovered on review of FLAIR (Figure 1(h)) and T1-w images. The MR signal of the venous thrombus also points towards an early subacute stage of the CVT, which is in keeping with a secondary presentation of the latter. However, the exact timing of the CVT relative to the aneurysmal SAH cannot be entirely proven.

Previous studies had shown that SAH results in central sympathetic activation promoting haemostasis and being associated with venous thromboembolic events such as deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolisation.5, 6 Such prothrombotic mechanisms may also account for the CVT being secondarily caused by aneurysmal SAH in our case.

In summary, we report the rare coincidental diagnosis of aneurysmal CVT and SAH secondary to an initially undiscovered aneurysmal rupture. We suggest that a ruptured aneurysm should be excluded by CTA or DSA in the presence of CVT with non-sulcal SAH in particular, as the clinical presentation of both entities may be similar. The presence of a ruptured aneurysm in patients with CVT also has special therapeutic implications due to increased risk from re-bleeding under therapeutic anticoagulation, and the ruptured aneurysm should be treated first.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

This work received no grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms Investigators. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms – risk of rupture and risks of surgical intervention. New Engl J Med 1998; 339: 1725–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stam J. Thrombosis of the cerebral veins and sinuses. New Engl J Med 2005; 352: 1791–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carvi y Nievas M, Haas E, Hollerhage HG, et al. Cerebral vein thrombosis associated with aneurysmal subarachnoid bleeding: implications for treatment. Surg Neurol 2004; 61: 95–98. discussion 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panda S, Prashantha DK, Shankar SR, et al. Localized convexity subarachnoid haemorrhage – a sign of early cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Eur J Neurol 2010; 17: 1249–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moussouttas M, Bhatnager M, Huynh TT, et al. Association between sympathetic response, neurogenic cardiomyopathy, and venous thromboembolization in patients with primary subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2013; 155: 1501–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naredi S, Lambert G, Eden E, et al. Increased sympathetic nervous activity in patients with nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 2000; 31: 901–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]