Abstract

During 2013, ST278 Klebsiella pneumoniae with blaNDM-7 was isolated from the urine (KpN01) and rectum (KpN02) of a patient in Calgary, Canada. The same strain (KpN04) was subsequently isolated from another patient in the same unit. Interestingly, a carbapenem-susceptible K. pneumoniae ST278 (KpN06) was obtained 1 month later from the blood of the second patient. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) revealed that the loss of carbapenem-resistance in KpN06 was due to a 5-kb deletion on the blaNDM-7-harboring IncX3 plasmid. In addition, an IncFIB plasmid in KpN06 had a 27-kb deletion that removed genes encoding for heavy metal resistance. Phylogenetic analysis showed that the K. pneumoniae ST278 from patient 2 was likely a descendant of KpN02 and that KpN06 was a close progenitor of an environmental ST278. It is unclear whether KpN06 lost the blaNDM-7 gene in vivo. This study detailed the remarkable plasticity and speed of evolutionary changes in multidrug-resistant K. pneumoniae, demonstrating the highly recombinant nature of this species. It also highlights the ability of NGS to clarify molecular microevolutionary events within antibiotic-resistant organisms.

Keywords: K. pneumoniae, ST278, carbapenemases, blaNDM-7, plasmid, microevolution

During the 1970s, Klebsiella pneumoniae emerged as an important cause of nosocomial urinary tract infections, respiratory tract infections, and bloodstream-associated infections [1]. The management of infections due to K. pneumoniae has been recently been complicated by the emergence of resistance to the carbapenems, which are often the last line of effective therapy available for the treatment of infections caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) isolates [2]. Several mechanisms are responsible for resistance to carbapenems in K. pneumoniae, but the production of carbapenemases remains the most clinically relevant [1]. The Ambler class B carbapenemases or metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) identified in K. pneumoniae are most often NDMs, while VIMs and IMP types are relatively rare in this species [1].

Between May 2013 and Dec 2014, 17 NDM-7–producing Enterobacteriaceae were isolated from 6 patients in Calgary, Canada. The resistance gene blaNDM-7 was harbored by an identical approximately 46-kb IncX3 plasmid among these isolates [3]. The index patient (patient 1) was admitted to the hospital in May 2013, and an ST278 carbapenem-resistant (CR) K. pneumoniae (KpN01) was isolated from his urine during June 2013. Subsequently, in August 2013, the same CR ST278 K. pneumoniae (KpN04) was identified from a different patient (patient 2) from the same unit. Interestingly, a carbapenem-susceptible (CS) ST278 K. pneumoniae (KpN06) was then obtained from the blood of patient 2 in September 2013. Molecular analyses showed that blaNDM-7 was absent in KpN06; however, the mechanism underlining the resistance gene loss was unclear. In this study, next-generation sequencing (NGS) was used to characterize 11 isolates (KpN01–11) collected from the 2 patients and their respective rooms, to explore the short-term microevolution of carbapenem resistance and nosocomial transmission of K. pneumoniae ST278.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Rectal and Environmental Screening for CR Enterobacteriaceae

Rectal swabs were placed into Copan M40 Transystem containing Amies gel transport medium, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (Atlanta, Georgia) protocol was used to screen for CR gram-negative bacteria [4]. Specimens collected from different surfaces in patient's rooms by means of sterile rayon swabs were cultured for K. pneumoniae by vortexing the swabs in 5 mL of tryptic soy broth, followed by incubation at 37°C for 24 hours. Samples exhibiting turbidity were plated on blood and MacConkey agars.

Bacterial Identification and Antimicrobial Susceptibilities

Isolates (KpN01–11) were identified using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (Vitek AMS; bioMerieux Vitek Systems, Hazelwood, Missouri). Minimum inhibitory concentrations of drugs (Supplementary Table 1) were determined using the Microscan NEG 38 panel (Siemens, Burlington, Canada) and interpreted by using 2015 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines for broth dilution [5].

β-lactamase Identification

Carbapenemases was detected using the modified Hodge test and the Mastdiscs ID inhibitor combination disks [6] (Mast Group, Merseyside, United Kingdom). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification and sequencing for β-lactamase genes were undertaken by using primers and conditions as previously described [7, 8].

Plasmid Analysis

Plasmid sizes were determined as previously described and assigned to plasmid incompatibility groups by PCR-based replicon typing [9, 10]. Conjugation experiments were performed by mating-out assays with nutrient agar containing meropenem 1 µg/mL and using Escherichia coli J53 (azide 100 µg/mL) as recipient.

Molecular Typing

Molecular typing was performed using standardized pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) [11] and multilocus sequencing typing [12].

NGS

DNA from KpN01 (from patient 1) and KpN06 (from patient 2) were extracted by standard methods (DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit, Qiagen, Toronto, Canada) and sent to the Génome Québec Innovation Centre (Montreal, Canada) for long-read sequencing with Pacific Biosciences RSII platform (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, California) to differentiate the chromosomal from plasmid DNA. Library preparation was optimized to include both long reads (>3 kb) and shorter, circular consensus sequencing reads. Four SMRT cells per isolate were used to ensure a minimum of 75× coverage of each genome.

KpN01–11 were sequenced with the MiSeq (Illumina, San Diego, California) platform. Libraries were prepared with the Nextera XT kit to produce paired end reads of 250 base pairs for a minimum predicted coverage of 75-fold. The high coverage Illumina reads were mapped to the PacBio assemblies for Kp01 and Kp06 by using Nesoni [13] to ensure high-quality reference genomes.

Assembly and Analysis

The KpN01 and KpN06 PacBio reads were assembled using the Hierarchical Genome Assembly Process, compiled specifically for quality trimming, de novo assembly, and polishing [14]. MiSeq reads were trimmed with TrimGalore (v.0.3.3; available at: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim galore) to remove sequencing adapters and reads with Phred quality scores of <25 and then were merged with FLASH (v.1.2.10) [15]. The merged and trimmed, paired-end fastq data were assembled with SPAdes (v. 3.0) [16] and assessed with QUAST [17]. All assemblies were annotated with Prokka (v.1.7) [18], the plasmids were typed with PlasmidFinder [19], and acquired antimicrobial resistance genes were identified using SRST2 [20]. The plasmids were compared using Mauve [21], and figures were produced with EasyFig [22].

Read Mapping and Variant Calling

The assembled PacBio genome of KpN01 (the index isolate) was used as the reference sequence for read mapping of the other isolates (KpN02–11) by using SMALT (v.0.7.5; available at: http://www.sanger.ac.uk/resources/software/smalt/), and the resultant mapping files were indexed and sorted with SAMtools (v. 1.0) [23] before variant calls were made with Freebayes (v. 0.9.8). Potential single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) were excluded if the mapping quality or the base quality score was <20 or if the minimum alternate fraction was <0.75. Core was defined as positions present in ≥90% of the genomes, and the resultant core SNVs were used to build a phylogeny, using the Core SNV Pipeline (available at: https://github.com/apetkau/core-phylogenomics). Larger insertion and/or deletion events (>1 nucleotide) were visually identified in Integrative Genomics Viewer [24] from the read mapping and were appended to the alignment as the presence or absence of character states. The chromosomal integration site of insertion sequence (IS) elements were examined by ISMapper, using the KpN01 genome as a reference [25].

Ethics Approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Calgary (REB13-0867_REN1).

RESULTS

CR K. pneumoniae Were Transferred From Patient 1 to Patient 2, Notwithstanding Infection Prevention and Control Measures

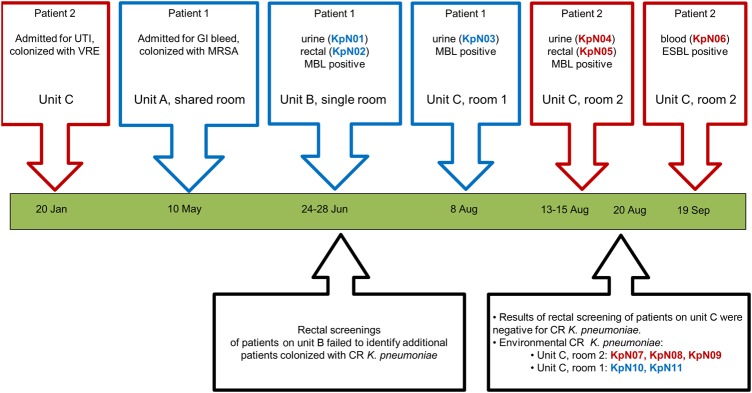

The clinical time line for patients 1 and 2 is summarized in Figure 1. Both patients were elderly and had comorbidities. Neither patient had travelled outside of Alberta, Canada, within 1 year of the hospital admission. Urine and rectal swab specimens positive for CR K. pneumoniae (KpN01 and KpN02) were obtained during June 2013 from patient 1 (he was asymptomatic during this episode) and prompted infection prevention and control protocols (including contact, isolation, and active surveillance procedures). Inner circle rectal swabs from patients in unit B were collected, but no additional positive swabs were found. Patient 1 was subsequently moved to unit C, where another positive urine sample was collected in early August (KpN03) before ciprofloxacin and gentamicin was administered for lower urinary tract infection (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The time line of events for 2 patients infected with multidrug-resistant (MDR) Klebsiella pneumonia within a single hospital. All events occurred within the same regional hospital in Calgary, Canada, between May and September of 2013. The clinical time line highlights the unit transfers and positive culture results from patient 1 (blue boxes). Infection prevention and control surveillance measures on unit 3 after MDR K. pneumoniae was isolated are shown in the black boxes below the dateline. The time line for patient 2 is presented in red boxes. Isolation measures were taken with patient 2 due to vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE) colonization found upon admission in May. Abbreviations: CR, carbapenem resistant; ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamase; GI, gastrointestinal; MBL, metallo-β-lactamase; UTI, urinary tract infection.

In mid-August, 2 CR K. pneumoniae isolates were recovered from the nephrostomy tube (KpN04) and rectal swab (KpN05) of an asymptomatic elderly patient (patient 2) in a room immediately adjacent to that of patient 1. Patient 2 previously (in January 2013) received ciprofloxacin for lower urinary tract infection, had early dementia, and reportedly entered the rooms of other patients. One patient on unit C received ertapenem during this time, and rectal screenings of all patients did not identify additional patients colonized with CR K. pneumoniae. Environmental screening revealed 5 additional CR K. pneumoniae isolates: KpN07, KpN08, and KpN09 from the room of patient 2 and KpN10 and KpN11 from the room of patient 1 (Figure 1). In September 2013, CS K. pneumoniae (KpN06) was isolated from a blood specimen from patient 2, and she was treated with intravenous colistin and meropenem but died due to sepsis.

Characterization of the CR K. pneumoniae Isolates Showed Them to Be Indistinguishable by Traditional Typing

Susceptibility, phenotypic, and molecular tests to characterize bacterial isolates (KpN01–11) are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. PCR and sequencing identified blaCTX-M-15, blaTEM-1, and blaSHV-27 in KpN01–11. They were also positive for blaNDM-7, with the exception of KpN06 (Supplementary Table 1). KpN01–11 belonged to ST278 and were indistinguishable by PFGE. Plasmid analysis showed that the isolates obtained from patient 1 and his room contained 3 plasmids (190 kb, 130 kb, and 50 kb), while isolates obtained from patient 2 and her room also contained 3 plasmids (190 kb, 100 kb, and 50 kb). Transconjugants from KpN01–11 (except KpN06) contained the 50-kb plasmid, were positive for blaNDM, and were typed with IncX replicon (Supplementary Table 1).

NGS Revealed That the Loss of Carbapenem Resistance Was Due to a 5-kb Deletion on a blaNDM-7–Harboring IncX3 Plasmid

KpN01 (a blaNDM-7–positive isolate from patient 1) and KpN06 (a blaNDM-7–negative isolate from patient 2) were chosen for in-depth genomics analysis. The genomic features of assemblies are presented in Table 1, and assembly summaries are in Table 2. The average coverage for the PacBio data was >100-fold for both isolates (both the circular consensus sequences and longer reads combined). The MiSeq data coverage was similar (approximately 100-fold coverage), and as a result, no single base call corrections were made.

Table 1.

Genomic Features of KpN01 and KpN06 Determined Using Pacific Biosciences RSII and Illumina MiSeq Platforms

| Feature | KpN01 | KpN06 |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence type | 278 | 278 |

| Date of isolation | 24 June 2013 | 19 September 2013 |

| Source | Urine | Blood |

| β-lactamase genes | blaNDM-7, blaCTX-M-15, blaTEM-1, blaSHV-27 | blaCTX-M-15, blaTEM-1, blaSHV-27 |

| Additional antimicrobial resistance genes | dfrA14, oqxA, oqxB, qnrB1, strA, strB, tetA, sul2 | dfrA14, oqxA, oqxB, qnrB1, strA, strB, tetA, sul2 |

| Size, base pairs | 5 307 114 | 5 309 013 |

| G + C content, % | 57.4 | 57.4 |

| Genes, no. | 5297 | 5302 |

| CDS, no. | 5153 | 5157 |

| Ribosomal RNA genes, no. | ||

| Overall | 25 | 25 |

| 16S | 8 | 8 |

| 23S | 8 | 8 |

| 5S | 9 | 9 |

| Transfer RNA genes, no. | 88 | 88 |

| Plasmids, no. | 4 | 4 |

| Prophages, no. | 7 | 7 |

| ICEs, no. | 3 | 3 |

| IS elements, no. | 10 | 12 |

| IS family (no.) | IS1 (1), IS3 (1), IS903 (2), ISKpn1 (4), ISKpn1400 (2) | IS1 (2), IS3 (1), IS5 (1), IS903 (2), ISKpn1 (4), ISKpn1400 (2) |

Abbreviations: CDS, coding DNA sequences; ICE, integrated conjugative element; IS, insertion sequence.

Table 2.

Chromosomal and Plasmid Variations Between KpN01 and KpN06 Determined Using the Pacific Biosciences RSII and Illumina MiSeq Platforms

| Reference | Start | End | Change | Polymorphism Type | Length (With Gaps) | Amino Acid Change | CDS Codon No. | CDS Position | Gene | Locus_Tag | Product |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KpN01_chromosome | 209 112 | 209 112 | C → A | SNP (transversion) | 1 | D → E | 156 | 468 | … | AQD68_01120 | Malonate decarboxylase subunit α |

| KpN01_chromosome | 1 337 919 | 1 337 919 | G → T | SNP (transversion) | 1 | R → L | 207 | 620 | … | AQD68_06685 | Dihydropteridine reductase |

| KpN01_chromosome | 1 921 164 | 1 921 164 | A → C | SNP (transversion) | 1 | T → P | 813 | 2437 | … | AQD68_09505 | ATP-dependent helicase |

| KpN01_chromosome | 3 974 440 | 3 974 440 | G → T | SNP (transversion) | 1 | R → L | 56 | 167 | … | AQD68_19845 | AraC family transcriptional regulator |

| KpN01_chromosome | 4 391 829 | 4 391 829 | G → T | SNP (transversion) | 1 | T → K | 60 | 179 | spr | AQD68_21945 | Lipoprotein Spr |

| KpN01_chromosome | 4 529 258 | 4 529 258 | A → C | SNP (transversion) | 1 | E → A | 106 | 317 | … | AQD68_22510 | Hypothetical protein |

| KpN01_chromosome | 4 623 276 | 4 623 276 | C → T | SNP (transition) | 1 | P → S | 88 | 262 | sirA | AQD68_22995 | 2-component system response regulator |

| KpN01_chromosome | 3 873 994 | 3 874 070 | … | Deletion | 77 | … | 81 | 241 | fhlA | AQD68_19305 | Formate hydrogen lyase activator |

| KpN01_chromosome | 3 969 188 | 3 969 187 | … | Insertion | 1199 | … | 49 | 145 | … | AQD68_19830 | Transposase |

| KpN01_chromosome | 5 189 933 | 5 189 932 | … | Insertion | 777 | … | 167 | 500 | … | AQD68_25885 | Transposase |

| pKpN01-SIL | 82 330 | 109 275 | … | Deletion | 26 945 | … | … | … | … | AQD68_28045–AQD68_28145 | … |

| pKpN01-NDM7 | 12 315 | 17 395 | … | Deletion | 5080 | … | … | … | … | AQD68_28350–AQD68_28390 | … |

Abbreviations: ATP adenosine triphosphate; CDS, coding DNA sequence; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

The chromosome lengths of KpN01 and KpN06 were 5.307 Mb and 5.309 Mb, respectively, similar in length to other K. pneumoniae genomes in public databases (range, 5.3–5.6 Mbp). They had an average G + C content of 57.4%, carried 25 ribosomal RNA genes, 88 transfer RNA genes, 7 putative prophages, and 3 integrated conjugative elements (ICEs). KpN01 had 10 IS elements, and KpN06 had 12 (Table 1). Table 2 details the variation in KpN06 with reference to KpN01, including 7 chromosomal SNVs that were intragenic, nonsynonymous mutations. KpN06 had a 77–base pair deletion within a formate hydrogen lyase activator (fhlA) transcription factor gene (locus no. AQD68_19305) and 2 transposase insertions: an IS5 (1.2 kb) was inserted into a transcriptional regulator gene (AQD68_19830), and an IS1 (777 base pairs) was inserted into a TetR family transcriptional regulator gene (AQD68_25885). The deletion and IS insertion mapping predicts that these genes were inactive in KpN06.

The long read sequencing led to parsing of 4 similar plasmids (that belonged to IncFII, IncFIB, IncX3, and ColE incompatibility groups) in KpN01 and KpN06.

The IncFII plasmids, pKpN01-CTX15 and pKpN06-CTX15, were highly similar (>99.9% nucleotide identities) and 190 072 base pairs in length, with 212 putative open reading frame sequences and a 57.1% G + C content. They harbored the following antimicrobial resistance genes: blaCTX-M-15, blaTEM-1, qnrB1, strAB, tetA, sul2, and dfrA14.

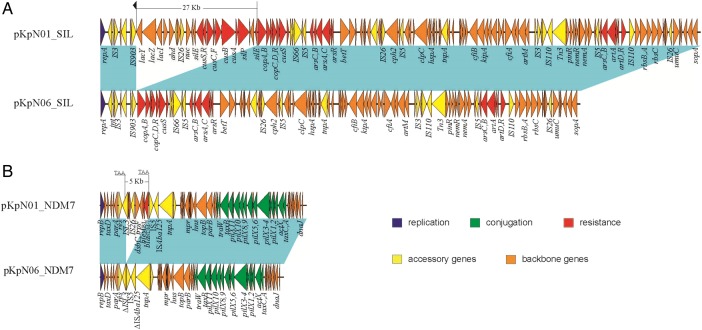

The IncFIB plasmids, pKpN01-SIL and pKPN06-SIL, were 134 064 and 107 110 base pairs in length, respectively (Figure 2). Interestingly, pKpN06-SIL from KpN06 had a 27-kb deletion (when compared to pKpN01-SIL) that contained the lac, sil, and partial cus operons, encompassing lacY-lacZ-lacI- ahd- nuc-silE- cusRS-cusCFBA -silP- silE genes. Of note is that the 27-kb deletion region was located immediately downstream of IS903 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

IncFIB and IncX plasmid structures from KpN01 and KpN06. Light blue shading denotes shared regions of homology, and open reading frames (ORFs) are portrayed by arrows and colored on the basis of predicted gene function. The small black arrow above pKpN01_SIL denotes the downstream invert repeat of IS903, while the 3–base pair putative direct repeats (TAA) of the 5-kb deletion on pKpN01_NDM7 are underlined.

The IncX3 plasmid from KpN01, pKpN01-NDM7, was 46 161 base pairs in length and harbored blaNDM-7 with no additional antibiotic resistance determinants. The detailed plasmid structure was reported in our previous study [3]. Interestingly, the InX3 plasmid from KpN06, pKpN06-NDM7, had a 5-kb deletion (when compared to pKpN01-NDM7) that included the region of ΔISL3-umuD-IS26-dsbC-trpF-bleMBL- blaNDM-7-ΔISAba125, which was consistent with the loss of carbapenem resistance. Further inspection indicated that the deleted region was bracketed by two 3-base pair direct repeats (TAA; Figure 2).

The smallest plasmids from KpN01 (pKpN01-COL) and KpN06 (pKpN06-COL) were 3223 base pairs in length, belonged to the ColE family and were nearly identical (>99.9% identity) to other ColE plasmids (ie, pKP13b [CP003994] [26], pCAV1321-3223 [CP011604], pCAV1492-3223 [CP011637], pCAV1311-3223 [CP011569], and pCAV1741-3223 [CP011652]).

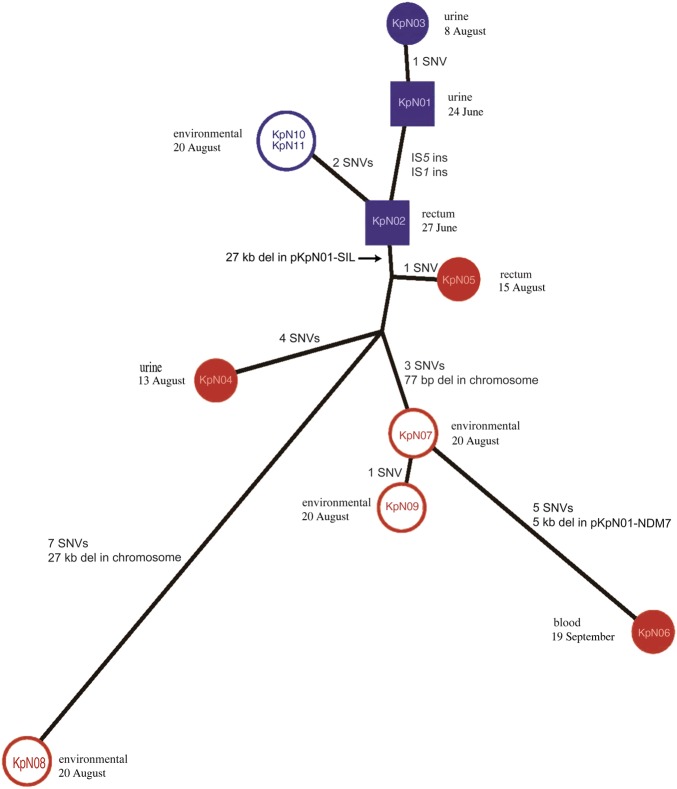

NGS Unveiled That the K. pneumoniae ST278 Strains Belonged to Different Clusters

In addition to the 2 completely closed ST278 genomes described above (KpN01 and KpN06), 9 more isolates were sequenced using the Miseq Illumina platform (Table 3). The sequencing reads were mapped to the KpN01 genome to identify SNVs and de novo assembled to examine large insertions and deletions. Figure 3 outlines the genetic changes observed between the clinical isolates recovered from patients 1 and 2 and their rooms. A maximum likelihood tree was produced by combining core SNVs with the larger insertion and deletion events as character states (presence/absence) appended to the alignment. The core SNV positions are presented in Supplementary Table 2 and summarized in a distance matrix in Supplementary Figure 1B, with the insertion/deletion events summarized in Supplementary Figure 1A. No short Indels (<10 base pairs) were identified in the 11 genomes.

Table 3.

Molecular Characterization of Klebsiella pneumoniae ST278 Isolates, Using Pacific Biosciences RSII and Illumina MiSeq Platforms

| Isolate and Platform(s), No. of Contigs (≥0 Base Pairs) | Total Length (≥0 Base Pairs) | N50 | Plasmid (Inc) | Genome Accessions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KpN01, Pacific Biosciences, Illumina | ||||

| 5 | Chromosome, 5 307 114 | … | … | CP012987 |

| 5 | pKpN01-CTX15, 189 853 | … | FII | CP012988 |

| 5 | pKpN01-SIL, 134 064 | … | FIB | CP012989 |

| 5 | pKpN01-NDM7, 46 161 | … | X3 | CP012990 |

| 5 | pKpN01-COL, 3223 | … | colE | CP012991 |

| KpN02, Illumina | ||||

| 167 | 5 634 950 | 193 867 | … | LLWT00000000 |

| KpN03, Illumina | ||||

| 219 | 5 628 465 | 94 505 | … | LLWU00000000 |

| KpN04, Illumina | ||||

| 279 | 5 576 435 | 52 252 | … | LLWV00000000 |

| KpN05, Illumina | ||||

| 125 | 5 603 554 | 310 445 | … | LLWW00000000 |

| KpN06, Pacific Biosciences, Illumina | ||||

| 5 | Chromosome, 5 309 013 | … | … | CP012992 |

| 5 | pKpN06-CTX15, 190 071 | … | FII | CP012993 |

| 5 | pKpN06-SIL, 107 110 | … | FIB | CP012994 |

| 5 | pKpN06-NDM7, 41 072 | … | X3 | CP012995 |

| 5 | pKpN06-COL, 3121a | … | colE | CP014305 |

| KpN07, Illumina | ||||

| 128 | 5 604 347 | 299 134 | … | LLWX00000000 |

| KpN08, Illumina | ||||

| 117 | 5 575 333 | 343 007 | … | LLWY00000000 |

| KpN09, Illumina | ||||

| 122 | 5 604 080 | 343 007 | … | LLWZ00000000 |

| KpN10, Illumina | ||||

| 159 | 5 634 927 | 230 303 | … | LLXA00000000 |

| KpN11, Illumina | ||||

| 154 | 5 643 345 | 276 468 | … | LLXB00000000 |

Abbreviation: N50, the length for which half of the bases of a draft genome are situated in contigs of that length or longer.

a This contig was added from the Illumina MiSeq assembly, matching the same plasmid in pKpN01-COL. It may not have been in the Pacific Biosciences assembly, owing to lower coverage.

Figure 3.

Maximum likelihood tree of all adaptive genetic changes from multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates associated with patients 1 and 2 over a 3-month period. Isolates from the biological specimens of each patient are solid colors, while isolates from environmental samples from each patient's room are open (blue, patient 1; red, patient 2). KpN01 and KpN02 are presented as squares to differentiate that these were collected while patient 1 was in unit 2 while all other isolates were collected from unit 3 (circles). All genetic events including core single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and insertion/deletions were included in the analysis, with the latter being added as presence/absence character states to the alignment to capture all of the genetic adaptations that occurred.

All genomes were closely related, with the core SNVs ranging from 0–14 (Supplementary Figure 1B). The addition of the larger insertion/deletion events to the phylogeny produced a tree that illustrates the genetic adaptations of K. pneumoniae within a short time scale. The 3 isolates from patient 1 (KpN01, KpN02, and KpN03) differed by 1 SNV, while the 2 environmental isolates from the room of patient 1 were identical. The 2 urinary isolates (KpN01 and KpN03), collected 45 days apart, differed by a single SNV (Table 2), while the rectal isolate (KpN02), collected 3 days after KpN01, acquired 2 IS insertions (at AQD68_19830 and _25885), resulting in the gene disruption of 2 putative regulators. These gene deletions could be associated with selection pressure change from the urinary to gastrointestinal tracts.

The 3 isolates from patient 2 (urine [KpN04], rectum [KpN05], and blood [KpN06]) differed by an average of 7 SNVs (Table 2). In addition to SNVs, KpN06 had a 77-base pair deletion in gene fhlA that truncated the gene and a 5-kb deletion in the IncX3 plasmid, encompassing the carbapenem resistance gene blaNDM-7. Interestingly, KpN06 was not a direct descent from KpN04 (the first K. pneumoniae isolate from patient 2) but was closer to 2 environmental isolates (KpN07 and KpN09) collected from the room of patient 2 (Figure 3). Moreover, the 27-kb deletion in pKpN01-SIL was only present in the strains obtained from patient 2 (KpN04, KpN05, and KpN06) or the environment within her room (KpN07, KpN08, and KpN09).

KpN01 (collected on 24 June) was the index isolate from patient 1; KpN02 (recovered from a rectal specimen from patient 1) was collected on 27 June, while KpN03 (recovered from a urine specimen from patient 1) was collected on 8 August. This time line would suggest that isolates from patient 2 would have evolved from KpN03. However, KpN02 acquired 2 IS insertions (at AQD68_19830 and _25885) that were absent in KpN01 and KpN03 but present in all of the isolates from patient 2 (ie, KpN04, KpN05, and KpN06), samples from her room (KpN07, KpN08, KpN09), and samples from the room of patient 1 (KpN10 and KpN11). This suggests that KpN04–11 were likely descendants from the rectal isolate from patient 1 (KpN02; Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

This report documented the transmission of highly similar blaNDM-7–harboring K. pneumoniae ST278 isolates (with 0–14 core SNVs differences) between 2 patients admitted to adjacent rooms on the same unit, despite infection prevention and control protocols. The case involving patient 1 had significant public health ramifications in Alberta as it suggested that NDM K. pneumoniae infections may have been acquired locally, independent of international travel [3]. Autochthonous acquisition of NDM-producing K. pneumoniae had previously been described in areas of nonendemicity, including Canada [27]; however, on his initial admission to unit 1 during May 2013, patient 1 shared a semiprivate room with 3 other patients. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that he contracted K. pneumoniae with blaNDM-7 from a patient who had traveled to an area of endemicity.

The K. pneumoniae from this study belonged to ST278, which was first reported in a neonatal unit from a university hospital in Turkey [28] and more recently in Syrian patients admitted to 2 different hospitals in northern Israel [29]. The Turkish ST278 harbored blaNDM-1, blaOXA-1, and blaSHV-27 and was isolated in 2013 from a newborn's rectal swab [28]. The ST278 from Israel was also present in rectal swabs and the most common ST associated with blaNDMs in that study [29]. However, complete genome sequencing of ST278 isolates were not conducted in these studies, and here we reported the first 2 completely sequenced ST278 genomes.

Genomic and phenotypic analyses demonstrated that ST278 KpN06 was CS and negative for blaNDM-7. The acquisition of carbapenem resistance in clinical K. pneumoniae had previously been reported, but the loss of carbapenem resistance is rare in published literature [1]. The in-vitro loss of blaNDM-1 by K. pneumoniae KPX was recently described from Taiwan; blaNDM-1 plasmid was maintained in high copy numbers when exposed to carbapenems, but carbapenem resistance was lost with the removal of selection pressure [30]. This was due to either reduced copy numbers of pKPX-1 or the loss of the blaNDM-1 via directed repeat mediated slippage.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to document the possible in vivo loss of blaNDM in K. pneumoniae. The deletion was due to the loss of a 5-kb blaNDM-7–harboring fragment on pKpN06-NDM7 (Figure 2). Detailed analysis of this 5-kb region identified a 3–base pair putative directed repeat sequence (TAA), and it is likely that this deletion is due to directed repeat mediated slippage, a scenario similar to the excision of 5.3-kb blaKPC-harboring element reported during Tn4401 truncation [31].

The 114-kb IncFIB plasmid pKpN06-SIL from KpN06 had 27-kb deletion that included the lac, sil, and cus operons (Figure 2). The lac operon is responsible for the transport and metabolism of lactose in Enterobacteriaceae and allows for the effective digestion of lactose when glucose is not available [32]. The proteins encoded by the sil operon mediate silver resistance by restricting the accumulation of silver in the cell through a combination of silver sequestration in the periplasm and active efflux [33]. The cus determinant consists of 2 operons, cusRS and cusCFBA, and confers copper and silver resistance [34]. Further examination the 27-kb deletion region revealed that it is located directly downstream of IS903, and it is likely that the 27-kb deletion was due to IS903-mediated adjacent deletion as described previously [35].

The use of reference mapping and inclusion of high-quality core genome SNVs to investigate the phylogenetic relationship between genomes is common practice [36–38]. However, the phylogenetic tree using only core SNVs did not accurately describe the short-term genetic adaptations that had occurred in our study. K. pneumoniae strains have large accessory genomes [37] in which nonvertical transmissions are a major source of short-term adaptive evolution in rapidly changing environmental conditions [39]. Thus the larger insertions/deletions (Supplementary Figure 1B) were appended to the core SNV alignment for phylogenetic analysis to accurately describe the genetic changes that transpired over a 3-month period (Figure 3). The variations, labeled on the tree branches, illustrated how the clinical epidemiology aligned with the genomic adaptations of bacteria. This phylogenetic analysis revealed fascinating microevolution aspects pertaining to mobile elements in K. pneumoniae over a short time frame (Figure 3). Our data suggest that the isolates from patient 2 were likely descendants from the rectal isolate from patient 1 (KpN02) and not from the urine isolates (KpN01 and KpN03). The 27-kb deletion in the pKpN01-SIL plasmid was the differentiating feature between patient 1–related isolates and patient 2–related isolates. On the basis of a 77–base pair chromosomal deletion, the CS blood isolate (KpN06) was more closely related to the environmental isolate (KpN07) collected from the room of patient 2 than clinical isolates obtained earlier (KpN04 and KpN05). It is unclear whether KpN06 lost the blaNDM-7 gene in vivo or whether patient 2 became infected with a strain found on an inanimate surface of the hospital room. The inclusion of insertion/deletion events outside core genome analysis can be useful for unveiling mechanisms underlying nosocomial spread of pathogens.

In summary, this study detailed the remarkable plasticity and speed of evolutionary changes in MDR K. pneumoniae, demonstrating the highly recombinant nature of this species, which included 3 deletion events, 2 chromosomal insertion events, and 7 SNVs that transpired over a 3-month period. Such rapid genetic fluctuation likely allows for the selection of strains with the ability to swiftly adapt to new environments. This study highlights the ability of NGS to clarify molecular microevolutionary event within antibiotic-resistant organisms.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at http://jid.oxfordjournals.org. Consisting of data provided by the author to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the author, so questions or comments should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by the Calgary Laboratory Services (grant 10009392) and the National Institutes of Health (grant 1R01AI090155 to B. N. K. and grant R21AI117338 to L. C.).

Potential conflicts of interests. J. D. P. previously received research funds from Merck and Astra Zeneca. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Pitout JD, Nordmann P, Poirel L. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, a key pathogen set for global nosocomial dominance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59:5873–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathers AJ, Peirano G, Pitout JD. The role of epidemic resistance plasmids and international high-risk clones in the spread of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Microbiol Rev 2015; 28:565–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen L, Peirano G, Lynch T et al. Molecular characterization by using next-generation sequencing of plasmids containing blaNDM-7 in Enterobacteriaceae from Calgary, Canada. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 60:1258–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Center for Disease Control. Guidance for the control of carbapenem-resitant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), 2012. Toolkit; http://www.cdc.gov/hai/organisms/cre/cre-toolkit/. Accessed August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: twenty fifth informational supplement, 2015. M100-S25 Wayne: CLSI. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doyle D, Peirano G, Lascols C, Lloyd T, Church DL, Pitout JD. Laboratory detection of Enterobacteriaceae that produce carbapenemases. J Clin Microbiol 2012; 50:3877–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pitout JD, Church DL, Gregson DB et al. Molecular epidemiology of CTX-M-producing Escherichia coli in the Calgary Health Region: emergence of CTX-M-15-producing isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007; 51:1281–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peirano G, Ahmed-Bentley J, Fuller J, Rubin JE, Pitout JD. Travel-related carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacteria in Alberta, Canada: the first 3 years. J Clin Microbiol 2014; 52:1575–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carattoli A, Bertini A, Villa L, Falbo V, Hopkins KL, Threlfall EJ. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J Microbiol Methods 2005; 63:219–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villa L, Garcia-Fernandez A, Fortini D, Carattoli A. Replicon sequence typing of IncF plasmids carrying virulence and resistance determinants. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010; 65:2518–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunter SB, Vauterin P, Lambert-Fair MA et al. Establishment of a universal size standard strain for use with the PulseNet standardized pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols: converting the national databases to the new size standard. J Clin Microbiol 2005; 43:1045–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diancourt L, Passet V, Verhoef J, Grimont PA, Brisse S. Multilocus sequence typing of Klebsiella pneumoniae nosocomial isolates. J Clin Microbiol 2005; 43:4178–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrison PaS, T. NESONI (0.1.2.8), 2014.

- 14.Chin CS, Alexander DH, Marks P et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat Methods 2013; 10:563–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magoc T, Salzberg SL. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011; 27:2957–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 2012; 19:455–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2013; 29:1072–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014; 30:2068–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carattoli A, Zankari E, Garcia-Fernandez A et al. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:3895–03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inouye M, Dashnow H, Raven LA et al. SRST2: rapid genomic surveillance for public health and hospital microbiology labs. Genome Med 2014; 6:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darling AE, Mau B, Perna NT. progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS One 2010; 5:e11147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sullivan MJ, Petty NK, Beatson SA. Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics 2011; 27:1009–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2078–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorvaldsdottir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform 2013; 14:178–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawkey J, Hamidian M, Wick RR et al. ISMapper: identifying transposase insertion sites in bacterial genomes from short read sequence data. BMC Genomics 2015; 16:667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramos PI, Picao RC, Almeida LG et al. Comparative analysis of the complete genome of KPC-2-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Kp13 reveals remarkable genome plasticity and a wide repertoire of virulence and resistance mechanisms. BMC Genomics 2014; 15:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kus JV, Tadros M, Simor A et al. New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase-1: local acquisition in Ontario, Canada, and challenges in detection. CMAJ 2011; 183:1257–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poirel L, Yilmaz M, Istanbullu A et al. Spread of NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae in a neonatal intensive care unit in Istanbul, Turkey. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:2929–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lerner A, Solter E, Rachi E et al. Detection and characterization of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in wounded Syrian patients admitted to hospitals in northern Israel. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2016; 35:149–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang TW, Chen TL, Chen YT et al. Copy Number Change of the NDM-1 sequence in a multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolate. PLoS One 2013; 8:e62774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen L, Chavda KD, Mediavilla JR et al. Partial excision of blaKPC from Tn4401 in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56:1635–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buvinger WE, Riley M. Nucleotide sequence of Klebsiella pneumoniae lac genes. J Bacteriol 1985; 163:850–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Randall CP, Gupta A, Jackson N, Busse D, O'Neill AJ. Silver resistance in Gram-negative bacteria: a dissection of endogenous and exogenous mechanisms. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015; 70:1037–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grass G, Rensing C. Genes involved in copper homeostasis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 2001; 183:2145–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weinert TA, Schaus NA, Grindley ND. Insertion sequence duplication in transpositional recombination. Science 1983; 222:755–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cairns MD, Preston MD, Lawley TD, Clark TG, Stabler RA, Wren BW. Genomic epidemiology of a protracted hospital outbreak caused by a toxin A-negative Clostridium difficile sublineage PCR Ribotype 017 strain in london, england. J Clin Microbiol 2015; 53:3141–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holt KE, Wertheim H, Zadoks RN et al. Genomic analysis of diversity, population structure, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae, an urgent threat to public health. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015; 112:E3574–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sahl JW, Del Franco M, Pournaras S et al. Phylogenetic and genomic diversity in isolates from the globally distributed Acinetobacter baumannii ST25 lineage. Sci Rep 2015; 5:15188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bergstrom CT, Lipsitch M, Levin BR. Natural selection, infectious transfer and the existence conditions for bacterial plasmids. Genetics 2000; 155:1505–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.