Abstract

Despite significant biomedical and policy advances, 199,000 infants and young children in sub-Saharan Africa became infected with HIV in 2013, indicating challenges to implementation of these advances. To understand the nature of these challenges, we sought to (1) characterize the barriers and facilitators that health workers encountered delivering prevention of vertical transmission (PVT) services in sub-Saharan Africa and (2) evaluate the use of theory to guide PVT service delivery. The PubMed and CINAHL databases were searched using keywords barriers, facilitators, HIV, prevention of vertical transmission of HIV, health workers, and their synonyms to identify relevant studies. Barriers and facilitators were coded at ecological levels according to the Determinants of Performance framework. Factors in this framework were then classified as affecting motivation, opportunity, or ability, per the Motivation-Opportunity-Ability framework (MOA) in order to evaluate domains of health worker performance within each ecological level. We found that the most frequently reported challenges occurred within the health facility level and spanned all three MOA domains. Barriers reported in 30% or more of studies from most proximal to distal included those affecting health worker motivation (stress, burnout, depression), patient opportunity (stigma), work opportunity (poor referral systems), health facility opportunity (overburdened workload, lack of supplies), and health facility ability (inadequate PVT training, inconsistent breastfeeding messages). Facilitators were reported in lower frequencies than barriers and tended to be resolutions to challenges (e.g. quality supervision, consistent supplies) or responses to an intervention (e.g. record systems and infrastructure improvements). The majority of studies did not use theory to guide study design or implementation. Interventions addressing health workers’ multiple ecological levels of interactions, particularly the health facility, hold promise for far-reaching impact as distal factors influence more proximal factors. Incorporating theory that considers factors beyond the health worker will strengthen endeavors to mitigate barriers to PVT service delivery.

Keywords: prevention of vertical transmission of HIV, health workers, health systems, performance, theory

Introduction

Nearly 35 million people are infected with HIV/AIDS globally, of which 71% live in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (UNAIDS, 2014). There, the collective routes of vertical transmission of HIV in utero, during delivery, or during breastfeeding remain a prevalent mode of HIV transmission (UNAIDS, 2014). Biomedical and policy advances have reduced vertical transmission rates to as low as 1–2% in efficacy studies and under 5% in “real-world” conditions (Chasela et al., 2010; Chi, Stringer, & Moodley, 2013; WHO, 2013). Despite these advances, 199,000 infants and young children in SSA were infected with HIV via vertical transmission in 2013 (UNAIDS, 2014). If the biomedical and policy innovations to prevent vertical transmission of HIV (PVT) were appropriately implemented, incidence would be lower.

There are significant barriers to PVT on both the provider and beneficiary sides. Three recent reviews have revealed that significant barriers to women’s uptake of PVT services span their many “ecological” levels of interactions (Gourlay, Birdthistle, Mburu, Iorpenda, & Wringe, 2013; hIarlaithe, Grede, de Pee, & Bloem, 2014; Tuthill, McGrath, & Young, 2013). However, less attention has been paid to the barriers and facilitators that health workers encounter in delivering PVT services. Yet health workers have been at the center of one of the major solutions to rapidly scale-up PVT services: “task shifting,” or the transfer of specific tasks to less specialized health workers (World Health Organization, 2008). In addition to increasing health system capacity, including the number of community health workers (CHWs), task shifting has created challenges in the health system including how to ensure adequate training, supervision, remuneration, and recognition (Callaghan, Ford, & Schneider, 2010; Mwai et al., 2013). Strikingly, systematic investigation of health workers’ experiences delivering PVT care is lacking.

Furthermore, the use of theoretical frameworks in PVT service delivery has yet to be assessed despite the continued development of health worker-focused theory. Health worker performance literature has progressed from its basis in individual motivational and cognitive theories (Locke & Latham, 2002; Ryan & Deci, 2000) to interpersonal and organizational constructs (Dickin, Dollahite, & Habicht, 2011; Okello & Gilson, 2015). Multi-level frameworks characterizing the complex factors necessary to target facility- and community-based health worker motivation and performance in low- and middle-income countries are increasingly common (Franco, Bennett, & Kanfer, 2002; Kok et al., 2014; Naimoli, Frymus, Wuliji, Franco, & Newsome, 2014). However, the degree to which these frameworks are engaged in the research on PVT service delivery is unclear.

Therefore, the objectives of this literature review were (1) to characterize the barriers and facilitators that health workers encounter in delivering PVT services in SSA and (2) to evaluate the use of theory to guide the design, implementation, and analysis of studies under review.

Methods

Search strategy

The keywords barriers, facilitators, HIV, prevention of vertical transmission of HIV, types of health workers, and their synonyms were searched in the PubMed and CINAHL databases (Supplemental Table 1). The search was limited to studies conducted in SSA and published in English before November 12, 2014. References were imported into Refworks to resolve duplicates and evaluate titles and abstracts.

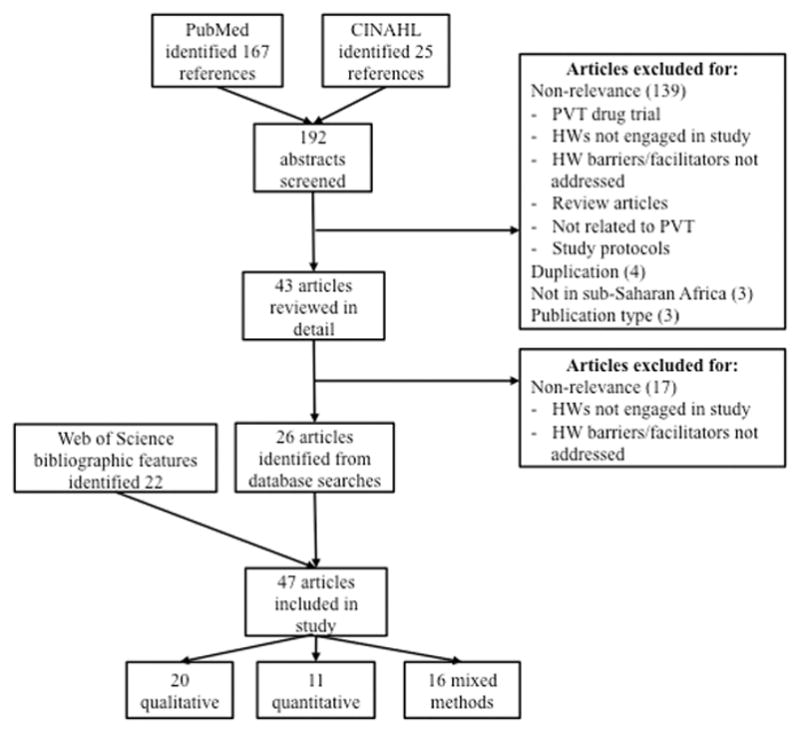

We initially identified 192 references and reduced this to 26 through the review process (Figure 1). Bibliographic features on Web of Science were used to identify additional articles which cited those 26 references. These articles were then reviewed for relevance, yielding an additional 22 articles.

Fig. 1.

Literature search strategy for barriers and facilitators to health workers’ delivery of prevention of vertical transmission of HIV (PVT) services

Data extraction and organization

Two co-authors independently extracted study characteristics, overall study findings, barriers, and facilitators. Differences were resolved through discussion. In cases of unclear study characteristics, the corresponding author was contacted up to two times and the senior author once via email for clarification.

Studies were subdivided by those conducted prior to 2007 and 2007 and later, when the 2006 World Health Organization recommendations for mother-infant dyad treatment and prophylaxis (WHO, 2006) and IYCF practices (WHO, 2007) began to be implemented.

Synthesis of results

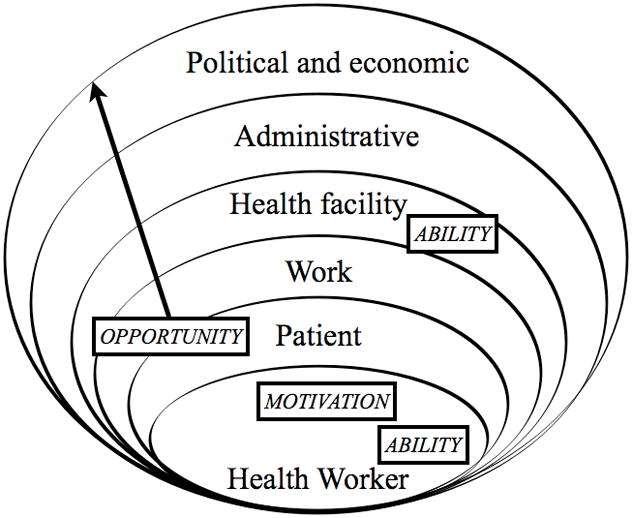

Two complimentary frameworks were integrated to guide this synthesis (Figure 2). The first was the Determinants of Performance research agenda which is embedded within an ecological framework (Rowe, de Savigny, Lanata, & Victora, 2005). The second is the Motivation-Opportunity-Ability framework (MOA), which posits that each of its three domains is necessary for optimal worker performance (Boudreau, Hopp, McClain, & Thomas, 2002; Siemsen, Roth, & Balasubramanian, 2008).

Fig. 2.

Integration of the Determinants of Performance and the Motivation-Opportunity-Ability frameworks

Determinants of Performance was used as the organizing framework because it places the health worker at the center and moves outwards for a total of six ecological “levels”. The health worker level focuses on individual factors (e.g. motivation, knowledge, skills). The patient level includes characteristics pertinent at point of care (e.g. patients’ severity of illness, demands for inappropriate treatments). The work level encompasses factors directly related to the worker’s mandate (e.g. complexity of clinical guidelines), while the health facility environment includes determinants of work environment such as caseload, availability of supplies, and supervision. The administrative environment consists of health system aspects beyond the health facility (e.g. support for supervisors, decentralization). Finally the political and economic environment specifies the educational infrastructure, which we modified to include health worker retention and political commitment.

The MOA was applied to describe health worker performance within each ecological level (Blumberg & Pringle, 1982). Motivation is the health worker’s desire and willingness to act and thus predominantly fits within the health worker level. Ability is the capability to execute the action, and its domain overlaps with health worker and some health facility factors. Finally, the opportunity domain consists of the the contextual factors that facilitate the action, and thus encompasses all levels beyond the individual.

Barriers and facilitators to delivery of PVT care were coded and organized according to the Determinants of Performance framework, to which iterative modifications were made in response to the presence of specific factors. Articles were then reviewed a second time with the modified framework to identify initially overlooked cases. Following this, factors were classified by MOA domains and ordered by percent of studies reporting that factor. A cutoff of 30% was used to describe “frequently reported” barriers or facilitators. We selected this rather low cutoff as appropriate to convey those barriers and facilitators that were most prominent, as not all studies evaluated all barriers and facilitators. (Actual frequencies can be seen in Tables 2 and 3.)

Table 2.

An ecological analysis of frequency of barriers to delivery of prevention of vertical transmission of HIV (PVT) services, by the motivation-opportunity-ability framework (MOA)a

| MOA Domain(s)b | Determinant of health worker performance | Manifestation | Studies conducted pre-2007 (n=20) | Studies conducted 2007-on (n=27) | Total studies (n=47) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Health worker factors | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| M | Intrinsic motivation | |||||||

| Reported stress, burnout, depression | 9 | 45.0% | 9 | 33.3% | 18 | 38.3% | ||

| Emotional burden of work (e.g. frustration of not effecting behavior change, infant HIV infection, patient hostility) | 6 | 30.0% | 6 | 22.2% | 12 | 25.5% | ||

| A | Knowledge | |||||||

| Poor understanding HIV transmission paths | 7 | 35.0% | 1 | 3.7% | 8 | 17.0% | ||

| Low general knowledge of health practices | 2 | 10.0% | 5 | 18.5% | 7 | 14.9% | ||

| A | Health worker approach to patient interactions | |||||||

| Lack of consideration of patient needs and preferences | 4 | 20.0% | 5 | 18.5% | 9 | 19.1% | ||

| Language barriers between health worker and patient | 1 | 5.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.1% | ||

| M | Extrinsic motivation | |||||||

| Inadequate remuneration (incl. late payment) | 3 | 15.0% | 5 | 18.5% | 8 | 17.0% | ||

| Other (e.g. low job security, fear of lawsuits) | 2 | 10.0% | 1 | 3.7% | 3 | 6.4% | ||

| Lack of recognition (incl. few promotion opportunities) | 2 | 10.0% | 1 | 3.7% | 3 | 6.4% | ||

| A | Poor self-efficacy | |||||||

| Low confidence in knowledge, interpretation of protocols | 2 | 10.0% | 2 | 7.4% | 4 | 8.5% | ||

| Discomfort diagnosing or counseling woman with HIV | 4 | 20.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 8.5% | ||

| M | Beliefs | Does not practice exclusive breastfeeding personally | 2 | 10.0% | 1 | 3.7% | 3 | 6.4% |

|

| ||||||||

| Patient factors | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| O | Stigma influenced patient behavior at point of care | |||||||

| Stigma, generally (mechanism unspecificed) | 4 | 20.0% | 10 | 37.0% | 14 | 29.8% | ||

| Patient hid HIV status during ANC or delivery | 1 | 5.0% | 10 | 37.0% | 11 | 23.4% | ||

| Patient refused HIV testing | 3 | 15.0% | 2 | 7.4% | 5 | 10.6% | ||

| O | Patient hid actual (non-adherent) PVT behaviors (e.g. “unsafe” IYCFc) | 1 | 5.0% | 2 | 7.4% | 3 | 6.4% | |

|

| ||||||||

| Work factors | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| O | Poor referral systems | 7 | 35.0% | 15 | 55.6% | 22 | 46.8% | |

| O | Unclear clinical IYCF guidelines (e.g. lack of existence, awareness)c | 3 | 15.0% | 7 | 25.9% | 10 | 21.3% | |

| O | Cumbersome record system (incl. high data volume, poor record-keeping) | 0 | 0.0% | 7 | 25.9% | 7 | 14.9% | |

|

| ||||||||

| Health facility environment | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| O | Over-burdened (e.g. understaffed, high workload, long hours) | 12 | 60.0% | 20 | 74.1% | 32 | 68.1% | |

| A | Inadequate PVT training | 13 | 65.0% | 14 | 51.9% | 27 | 57.4% | |

| O | Lack of supplies (e.g. HIV-specific medicines and tests, other medicines, contraceptives) | 11 | 55.0% | 16 | 59.3% | 27 | 57.4% | |

| A | Incorrect/inconsistent IYCF messagesc | 12 | 60.0% | 8 | 29.6% | 20 | 42.6% | |

| O | Poor infrastructure | |||||||

| Lack of private and appropriately sized spaces for PVT counseling and child delivery | 6 | 30.0% | 8 | 29.6% | 14 | 29.8% | ||

| Inadequate laboratory equipment | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 11.1% | 3 | 6.4% | ||

| Basics (e.g. water, electricity) | 1 | 5.0% | 2 | 7.4% | 3 | 6.4% | ||

| A | Poor supervision (incl. feedback on performance) | 4 | 20.0% | 9 | 33.3% | 13 | 27.7% | |

| O | Inter-cadre issues encountered by lay and community-based health workers | |||||||

| Unclear roles | 2 | 10.0% | 3 | 11.1% | 5 | 10.6% | ||

| Poor relations between clinical and lay/community-based health workers | 2 | 10.0% | 2 | 7.4% | 4 | 8.5% | ||

| A | Professional isolation | 1 | 5.0% | 1 | 3.7% | 2 | 4.3% | |

|

| ||||||||

| Administrative environment | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| O | Poor PVT planning and program coordination | |||||||

| Service fragmentation (e.g. separate of PVT and ANC clinics) and poor coordination between them | 5 | 25.0% | 8 | 29.6% | 13 | 27.7% | ||

| Lack of government funding for PVT | 3 | 15.0% | 4 | 14.8% | 7 | 14.9% | ||

| Poor planning for implementation or scale-up PVT | 2 | 10.0% | 4 | 14.8% | 6 | 12.8% | ||

| Poor allocation of equipment and supplies | 1 | 5.0% | 2 | 7.4% | 3 | 6.4% | ||

| M | Lack of health system recognition for lay and community-based health workers | 2 | 10.0% | 2 | 7.4% | 4 | 8.5% | |

| O | Foreign donors | |||||||

| Donor agenda discordant with country’s needs | 1 | 5.0% | 3 | 11.1% | 4 | 8.5% | ||

| Supplies inconsistent | 1 | 5.0% | 3 | 11.1% | 4 | 8.5% | ||

| A | Managerial issues | |||||||

| Manager did not understand socio-cultural context | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 7.4% | 2 | 4.3% | ||

| Manager unaware of provincial guidelines | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 3.7% | 1 | 2.1% | ||

| Did not address health worker concerns; poor communication | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 7.4% | 2 | 4.3% | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Political and economic environment | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| O | Health worker turnover, emigration to cities and high-income countries | 1 | 5.0% | 5 | 18.5% | 6 | 12.8% | |

Notes:

The ecological analysis expanded by study are available in Supplemental Table 2a for studies conducted prior to 2007 and in Supplemental Table 2b for studies conducted in 2007 and later

MOA Domains: M - motivation; O - opportunity; A - ability

IYCF - infant and young child feeding

Table 3.

An ecological analysis of frequency of facilitators to delivery of prevention of vertical transmission of HIV (PVT) services, by the motivation-opportunity-ability (MOA) frameworka

| MOA Domain(s)b | Determinant of health worker performance | Manifestation | Studies conducted pre-2007 (n=20) | Studies conducted 2007-on (n=27) | Total studies (n=47) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Health worker factors | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| M | Intrinsic motivation | |||||||

| Reward of effecting behavior change, patient health | 7 | 35.0% | 2 | 7.4% | 9 | 19.1% | ||

| Values work | 4 | 20.0% | 1 | 3.7% | 5 | 10.6% | ||

| A | Feels knowledgeable about HIV practices | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 11.1% | 3 | 6.4% | |

| M | Extrinsic motivation | |||||||

| Satisfied with remuneration (salary, incentives) | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 7.4% | 2 | 4.3% | ||

| Others value importance of work | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 3.7% | 1 | 2.1% | ||

| Professional development opportunities | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 3.7% | 1 | 2.1% | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Patient Factors | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| O | Health worker goes out of way to support patient interactions | 4 | 20.0% | 3 | 11.1% | 7 | 14.9% | |

|

| ||||||||

| Work Factors | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| O | Improved record system | 2 | 10.0% | 2 | 7.4% | 4 | 8.5% | |

|

| ||||||||

| Health facility environment | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| A | Quality training and regular refresher trainings | 3 | 15.0% | 3 | 11.1% | 6 | 12.8% | |

| A | Quality supervision (e.g. performance feedback, regular meetings) | 2 | 10.0% | 2 | 7.4% | 4 | 8.5% | |

| O | Consistent supplies | 1 | 5.0% | 3 | 11.1% | 4 | 8.5% | |

| O | Good staff relations, sense of teamwork | 1 | 5.0% | 1 | 3.7% | 2 | 4.3% | |

| O | Improved infrastructure | |||||||

| Updated equipment and facility | 1 | 5.0% | 1 | 3.7% | 2 | 4.3% | ||

| Private counselling rooms | 1 | 5.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.1% | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Administrative environment | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| O | NGO support | |||||||

| Technical | 2 | 10.0% | 3 | 11.1% | 5 | 10.6% | ||

| Financial | 1 | 5.0% | 2 | 7.4% | 3 | 6.4% | ||

| O | Non-clinical cadres delivered PVT services | |||||||

| Community health workers | 1 | 5.0% | 3 | 11.1% | 4 | 8.5% | ||

| Lay counsellors | 2 | 10.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 4.3% | ||

| TBAs referred women for clinical PVT care | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 3.7% | 1 | 2.1% | ||

| O | Quality PVT program coordination | |||||||

| Service integration for PVT | 1 | 5.0% | 2 | 7.4% | 3 | 6.4% | ||

| Group HIV counselling | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 3.7% | 1 | 2.1% | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Political and economic environment | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| O | Political will dedicated to PVT | 1 | 5.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.1% | |

The ecological analysis expanded by study are available in Supplemental Table 2a for studies conducted prior to 2007 and in Supplemental Table 2b for studies conducted in 2007 and later

MOA Domains: M - motivation; O - opportunity; A - ability

Results

Study characteristics

Of the 47 eligible studies, 20 were conducted prior to 2007 and 27 were conducted in 2007 and later (Table 1). Studies took place in 16 different countries, with South Africa (n=16) the most frequently represented country and southern (n=31) and eastern (n=15) Africa the most represented regions. Studies were most frequently conducted in both urban and rural settings (n=20), followed by solely rural (n=14), urban (n=12), and unclear (n=1) settings. The majority of studies were conducted within the public health system (n=26), followed by both public and private (n=8), community-based (n=3), private only (n=2), and unclear (n=8). Eight studies included community-based health workers such as CHWs or traditional birth attendants (TBAs).

Table 1.

Key characteristics of studies included in review of barriers and promoters to delivery of prevention of vertical transmission of HIV (PVT) services in sub-Saharan Africa (n=47)

| No. | Author(s), Year | Year conducted | Country | Settinga | Study methodologiesb | Participantsc | Objective | Theoretical framework |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Studies conducted prior to 2007 (n=20)

| ||||||||

| 1 | Buskens and Jaffe, 2008 | 2003 | Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland | Urban and rural: 11 health centers and hospitals a | FGDs, IDIs, participant observation | 5 PVT physicians or coordinators, 10 nurses, 7 counsellors, 167 mothers, 11 pregnant women, 32 relatives | To explore the perceptions and experiences of mothers and providers on infant feeding counseling in the context of PVT | None |

| 2 | Chopra and Rollins, 2008 | 2003 | Botswana, Kenya, Malawi, Uganda | Urban and rural: 29 health centers | FGDs, participant observation, surveys | 334 HWs, 640 patients in counselling observations, men and women (in 34 FGDs) | To assess provider knowledge and quality of infant feeding counseling of PVT programs | None |

| 3 | Creek et al., 2007 | 2003 | Botswana | Urban and rural: 12 clinics, 1 maternity hospitala | Surveys | 66 midwives, 16 counsellors, 504 pregnant/postpartum women | To characterize the factors influencing women to accept or refuse an HIV test; to describe what constitutes adequate PVT knowledge for HWs | None |

| 4 | de Paoli et al., 2002 | 2000–2001 | Tanzania | Urban: 1 private hospital | IDIs | 2 doctors, 16 nurses, 5 counsellors | To evaluate the quality and perceived influence of infant feeding counseling on HIV-infected pregnant women | None |

| 5 | Delva, 2006 | 2003 | South Africa | Urban: 1 public hospital | SSIs | 3 program coordinators, 3 doctors, 1 pharmacist, 7 midwives | To explore the challenges and potential solutions for use of single-dose Neverapine for PVT | None |

| 6 | Doherty et al., 2005 | 2002 | South Africa | Urban and rural: 18 PVT sitesa | Records review, SSIs | HWs (unspecified) | To evaluate the uptake and performance of South Africa’s national pilot PVT program | None |

| 7 | Fadnes et al., 2010 | 2003–2005 | Uganda | Rural: public hospitals, health centers, and NGO projectsa | FGDs, IDIs, surveys | 18 clinical officers, nurses and midwives, HIV-exposed women (in 7 FGDs), community members (in 8 FGDs), 727 HIV-uninfected and 235 HIV-infected mothers | To assess delivery of infant feeding counselling; to evaluate the experiences of providers and mothers delivering and receiving this counseling | None |

| 8 | Horwood et al., 2010(B) | 2006 | South Africa | Urban and rural: public health centersa | FGDs | Nurses, mothers and family members | To characterize attitudes and experiences of nurses and mothers during HIV testing in the integrated management of childhood illness | None |

| 9 | Ledikwe et al., 2013 | 2002–2010 | Botswana | Urban, peri-urban, and rural: public health centersa | Counselling observations, client exit interviews, FGDs, IDIs | 17 policymakers, 23 district coordinators, 39 HWs (physicians, nurses, midwives, social workers), 400+ lay counsellors, 47 patients | To evaluate the effectiveness and contributions of lay HIV counsellors | None |

| 10 | Leshabari et al., 2007 | 2003–2004 | Tanzania | Urban: 2 public hospitals and 2 public health centers | FGDs, IDIs | 25 nurses | To explore experiences and concerns of nurses providing infant feeding counselling in the context of PVT | None |

| 11 | Levy, 2009 | 2004–2005 | Malawi | Rural: 1 public clinic | FGDs, longitudinal IDIs, participant observation | 21 health personnel (PVT policymakers, aid organizations, medical staff, nurses), 55 HIV-infected women | To characterize women’s expectations and experiences of HIV treatment and care | None |

| 12 | Malema et al., 2010 | 2006 | South Africa | Urban: 15 public health centers | SSIs | 15 lay counsellors | To characterize the experience of lay counselors who provide HIV counseling and testing | None |

| 13 | Mazia et al., 2009 | 2006–2007 | Swaziland | Urban and rural: 3 public and private hospitals and 4 public MCH units | Postnatal care training intervention; HW interviews, patient exit interviews, patient observations, health center assessment | 134 HWs (mostly nurses) trained. 700 patients (HIV-infected and -uninfected) | To evaluate the feasibility of integration of postnatal care with PVT care following intervention (training) | None |

| 14 | Medley et al, 2010 | 2005 | Uganda | Urban and rural: 10 public and private clinicsa | SSIs | 3 center managers, 27 counsellors | To characterize the challenges of provider-initiated testing and counselling | None |

| 15 | Nuwagaba-Biribonwoha et al., 2007 | 2003 | Uganda | Rural: 5 public and private hospitals | IDIs | 5 PVT coordinators, 5 doctors, 5 counsellors | To characterize the experiences of key HWs in early implemention of PVT services | None |

| 16 | Perez et al., 2008 | 2006 | Zimbabwe | Rural: community-based | FGDs, surveys | 72 TBAs (FGDs), 627 women (surveys) | To evaluate the acceptability and feasibility of TBAs’ inclusion in MCH through participation in PVT | None |

| 17 | Piwoz et al., 2006 | 2002 | Malawi | Urban and rural: health centersa | SSIs | 5 clinical officers and medical assistant, 14 nurses and midwives | To characterize health workers’ attitudes and infant feeding counselling messages in the context of PVT | None |

| 18 | Shah et al., 2005 | 2000 | South Africa | Rural: 1 public hospital and 14 public health centers | SSIs, surveys | 14 doctors, 41 nurses, 16 CHWs | To assess HW breastfeeding and PVT knowledge | None |

| 19 | Simba et al., 2008 | 2005 | Tanzania | Urban and rural: 60 predominantly public health centersa | Participant observation, records review | 435 service providers | To assess the impact of integrating and scaling up PVT into routine MCH services on staff workload | None |

| 20 | Wanyu et al., 2007 | 2002–2005 | Cameroon | Rural: community-based | TBA PVT training intervention; SSIs | 30 TBAs | To evaluate the effectiveness of TBAs in delivery of PVT care | None |

|

| ||||||||

|

Studies conducted in 2007 and later

| ||||||||

| 21 | Agadjanian and Hayford, 2009 | 2008 | Mozambique | Urban and rural: 6 public health centers | Participant observation, SSIs | 2 CHW coordinators, 16 nurses, 4 CHWs | To characterize how integration of PVT services in MCH units shapes provider-client interactions and reproductive choices of HIV-infected women | None |

| 22 | Asefa and Mitike, 2014 | 2010 | Ethiopia | Urban: 1 public hospital, 3 public health centers, 2 private hospitals, 2 private health centers | Surveys | 31 nurses, midwives, public health officers, and physicians, 423 women seeking ANC | To characterize maternal satisfaction with PVT services and implementation challenges faced by providers | None |

| 23 | Chinkonde et al., 2010 | 2009 | Malawi | 1 peri-urban and 1 rural public PVT clinic | SSIs, participant observation | 5 policymakers, 2 doctors, 8 nurses, 1 lay counsellor | To assess policymakers’ and HWs’ experiences with adapting and implementing global breastfeeding guidelines to national recommendations | None |

| 24 | Doherty et al., 2009 | 2007 | South Africa | Rural: 18 public health centers | Quality improvement intervention; observation, surveys, workshops | 15 center managers, 35 lay counsellors | To evaluate a participatory intervention seeking to improve quality of care in integrated PVT programs | Expanded health systems approach |

| 25 | Falnes et al., 2010 | 2007–2008 | Tanzania | Urban and rural: 5 public clinics | Counselling observations, FGDs, IDIs, surveys | 5 nurse counsellors (IDIs), mothers (in 4 FGDs, 8 IDIs, 311 surveys) | To characterize experiences of mothers and nurse counsellors during PVT | None |

| 26 | Geelhoed et al., 2013 | 2009–2010 | Mozambique | Rural: 6 public health centers | Integration of PVT services itervention; service delivery statistics, SSIs | 70 MCH providers | To assess the viability of integrated PVT care and follow-up of HIV-exposed infants | None |

| 27 | Hamela et al., 2014 | 2008 | Malawi | Urban: 4 public PVT sites | TBA training intervention, log review, FGDs | 21 TBAs | To evaluate the benefits of incorporating TBAs into HC-based PVT services | None |

| 28 | Horwood et al., 2010(A) | 2007–2008 | South Africa | Peri-urban and rural: 1 public health center and 1 public hospital | Surveys | 25 nurses, 27 lay counsellors, 882 mothers | To evaluate implementation and integration of PVT with MCH. To describe the responsibilities of nurses and counsellors | None |

| 29 | Israel-Ballard et al., 2014 | 2008 | Kenya | 12 public clinicsa | Counselling observations, exit interviews, SSIs | 80 mothers, 11 nurses/nutritionists | To evaluate how infant feeding counselors manage challenges encountered in delivery of care | None |

| 30 | Kim et al., 2013 | 2010 | Zambia | Urban and rural: 8 military clinics | Observations, surveys | 4 medical assistant, 10 clinical officers, 1 pharmacist, 14 nurses, 11 midwives | To evaluate provider performance for PVT and ART care and perception of work environment | None |

| 31 | Kwapong et al., 2014 | 2011 | Ghana | Urban: 5 clinicsa | FGDs, IDIs, surveys | 12 nurses and midwives (IDIs), 40 pregnant women (5 FGDs), 300 pregnant women (surveys) | To characterize heath center factors’ influence on on HIV testing and counseling during ANC to inform implementation | None |

| 32 | Labhardt et al., 2009 | 2007–2008 | Cameroon | Rural: 62 public and private clinics and 8 public hospitals | Supply and equipment intervention; inventory, surveys | 102 nurses | To evaluate effectiveness of intervention on equipment availability and staff PVT knowledge | None |

| 33 | Lippmann et al., 2012 | 2007 | Malawi | Urban: community based | FGDs | 17 TBAs (registered) | To assess the willingness and feasibility of TBAs to provide NVP to infants and mothers | None |

| 34 | Mnyani and McIntyre, 2013 | 2009 | South Africa | Peri-urban: 10 public clinics | Surveys | 44 nurses, 30 lay counsellors, 6 other HWs, 201 HIV-infected women | To assess quality of PVT care via the knowledge and experiences of HIV-infected women and HWs | None |

| 35 | Peltzer et al., 2010 | 2008 | South Africa | Urban and rural: 44 public health centers including 5 hospitals | IDIs, register and records review, SSIs | 31 program coordinators, 11 health center managers, 8 HWs | To assess challenges and proposed solutions to implemention of PVT care; to assess of clinic registers and health records | None |

| 36 | Rispel et al., 2009 | 2007 | South Africa | Urban and rural: 3 hospitals and 20 clinicsa | IDIs, surveys | 20 PVT managers, 9 nurses, 18 lay counsellors, 4 maternity staff, 54 TBAs, 47 TMPs, 296 clinic users, 8 community organizations | To assess missed PVT opportunities to inform evaluation of program implementation | Developed framework (based on Alma Ata Declaration, formative work) |

| 37 | Rujumba et al., 2012 | 2010 | Uganda | Rural and peri-urban: 10 public and private hospitals and health centers | IDIs, observation, SSIs | 2 doctors, 3 clinical officers, 15 nurses, 4 counsellors | To characterize HW experineces in implementation in order to identify necessary steps to strengthen PVT service delivery | None |

| 38 | Sarker et al., 2009 | 2007 | Burkina Faso | Rural: 4 public health centers | Counselling observations, IDIs | 1 health officer, 1 PVT coordinator, 1 midwife, 6 counsellors, 16 pregnant women | To evaluate implementation of opt-in HIV testing services in the context of scaling-up PVT programming | None |

| 39 | Shayo et al., 2013 | 2011 | Tanzania | Urban and rural: public and faith baseda | FGDs, IDIs | 22 HWs delivering PVT services, 11 district and regional managers, 10 health center PVT in-charges | To assess the priority setting process in planning the PVT program at district level | None |

| 40 | Sprague et al., 2011 | 2008–2009 | South Africa | 1 urban public hospital, 3 peri-urban public health centers | Health records review, IDIs | 38 HWs (public health specialists, doctors, nurses, lay counsellors), 83 HIV-infected women, 32 caregivers of HIV-infected children | To characterize the barriers for patients and providers in the continuum of PVT care | None |

| 41 | Stinson and Myer, 2012 | 2007–2008 | South Africa | Urban: 4 public primary health centers, 2 public hospitals | SSIs | 3 service managers, 9 doctors, 1 nurse, 1 counsellor, 28 HIV-infected pregnant and postpartum women | To characterize barriers to initiating life-long ART during pregnancy and challenges to postpartum retention in HIV care | None |

| 42 | Turan et al., 2012 | 2009–2011 | Kenya | Rural: 4 hospitals, 8 health centersa | Prospective cluster randomized controlled trial for service integration (HW training) | 1,172 HIV-infected pregnant women | To evaluate the effects of integrating HIV treatment into ANC clinics | None |

| 43 | Uwimana et al., 2012(A) | 2008 | South Africa | Rural: public and private, 4 hospitals, 7 clinics, 5 NGOs | FGDs, IDIs | 29 managers, 36 counsellors | To characterize managers’ and CHWs’ perceptions of barriers related to collaboratively implementing TB/HIV/PVT services | None |

| 44 | Uwimana et al., 2012(B) | 2008–2009 | South Africa | Rural: public and private, 42 hospitals, 5 clinics, 33 NGOs | FGDs, household surveys, IDIs, NGO and health center audits | Health managers, 36 counsellors, 3,867 households | To characterize NGO and CHW engagement in and barriers to collaborative implementation of integrated TB/HIV/PVT services | None |

| 45 | Vernooij and Hardon, 2013 | 2008 | Uganda | Rural: 1 public clinic | SSIs, observations | 2 PVT managers, 2 clinical officers, 2 midwives, 2 counsellors, 2 lab techs, 2 CHWs | To elucidate different HW cadres’ perceptions and experiences in obtaining informed consent and conducting opt-out HIV testing in the context of PVT | Foucalt’s theory of governmentality |

| 46 | Watson-Jones et al., 2012 | 2008–2009 | Tanzania | Urban: 3 public health centers, 2 public hospitals | Intervention for referrals; ANC observations, prospective cohort of HIV-infected women, surveys | 30 HWs, 9 observations, 403 HIV-infected women | To evaluate the drop-out of care of HIV-infected women from the cascade of PVT services; to identify and characterize potential barriers to PVT service effectiveness | None |

| 47 | Yeap et al., 2010 | 2008 | South Africa | Urban and rural: 6 private heath centers | IDIs | 7 doctors, 5 nurses, 9 counsellors, 3 care center staff, 21 caregivers | To describe the barriers and facilitators to uptake of HIV care among children | None |

Notes:

Unclear breakdown of urban/rural and/or public/private facility numbers

Cross sectional unless otherwise noted

Some specialized health workers were grouped into general cadres to streamline categorization; e.g. “doctors” included specialists (e.g. pediatricians and obstetricians) and “nurses” included professional and auxiliary nurses

Technical abbreviations: ART - anti-retroviral therapy; CHW - community health worker; HW - health worker; MCH - maternal and child health; NGO - non-governmental organization; NVP - nevirapine; PVT prevention of vertical transmission; TB - tuberculosis; TBA - traditional birth attendant; TMP - traditional medical practitioner Method abbreviations: FGD - focus group discussion; IDI - in-depth interview; SSI - semi-structured interview

Use of theory

The vast majority of authors did not substantively report using non-methodological theory to guide the design, implementation, or analysis of their study. Exceptions included the expanded health systems approach [Study #24, Table 1], a self-developed framework [#36], and Foucault’s theory of governmentality [#45]. Nine of the 36 studies that collected qualitative data reported using analytic theories to guide qualitative analysis [#7,9,10,14,15,37,40,44,45].

Barriers to delivery of PVT services

Motivation

At the health worker level, intrinsic motivation was frequently challenged by stress, burnout, and depression [#1,4,5,8–12,14,21,30,34,35,37,39,40,45,47], as well as the emotional burden that accompanied caring for patients living with HIV [#1,4,8,10,14,15,21,34,37,40,45,47] (Table 2). For example, health workers interviewed in Uganda reported high stress from repeatedly counseling young pregnant women following an HIV-positive diagnoses [#14]. Barriers to extrinsic sources of motivation (e.g. dissatisfaction with remuneration [#5,9,10,21,22,34,44], late payment [#40], lack of recognition [#9,12,33]) were reported in comparatively lower frequencies. At the administrative level, four of the 15 studies including lay and community-based workers found these cadres were not formally recognized [#12,16,33,44].

Opportunity

Health workers feeling chronically overburdened was the most frequently reported challenge overall and occurred at the health facility level [#1,4–7,9–11,14,15,19,20–23,25,26,29–31,34–40,42,43,45–47]. For example, providing PVT services within antenatal care (ANC) increased workload, often without a commensurate increase in staffing [#34], resulting in counselors feeling rushed by long lines and inability to take breaks [#14]. In early roll-out of PVT services, counseling was often provided by nurses moonlighting as counselors, contributing to their overburdened feeling [#4,10]. Other frequently reported health facility challenges included lack of supplies (e.g. PVT-specific medicines [#7,11,16,20,24–26,32,33,36,40], rapid HIV tests [#6,9,26,31,35,36,40,42]), and private spaces for PVT counseling and delivery [#5–7,9,14,15,24,25,31,32,35,37,38,47].

Challenges at the patient and work levels emerged as more problematic in studies conducted in 2007 onwards. Patients reportedly hid their HIV-infected status, e.g. removing identifying stickers from their health card [#6]. Other behaviors at point of care attributed in part to stigma included women’s refusal of HIV testing [#14,15,26], skipping counseling sessions [#1,12], and delivering with a TBA [#16,27,33,43,44], although these overlap with sociocultural factors. Poor referral systems resulting in patients lost to follow-up [#1,4,10,11,14,15,20,23,27–31,35–38,40,41,43,44,46], cumbersome record systems [#21,24,26,27,35,36,40], and confusion around clinical IYCF guidelines [#1,17,20,23,24,35,36,38,39,46] were work level factors reported more frequently in studies conducted 2007 onwards.

Administrative challenges were reported slightly more frequently in studies conducted 2007 onwards but less frequently than other ecological levels overall. The most frequently reported barriers were the fragmentation of PVT services [#1,8,10,11,13,21,23,37,38,40,41,43,46], implications of which include the “de facto segregation” of HIV-infected women that could potentiate stigma [#21], missed opportunities for delivery of PVT services [#40] including IYCF counseling [#23] and family planning and condom usage [#36]. Lack of government funding [#11,14,15,33,37,39,43], poor planning for launch or scale-up of PVT services [#5,10,32,37,38,43], and discordant foreign donor agendas [#7,37,39,44] were reported in lower frequencies and without obvious time trends.

Ambiguity around work roles appeared to be unique to lay and community-based health workers in this review. For example, these cadres reported not feeling respected by clinical health workers [#12,44], and less than one-third of lay health workers had received a written job description in one study [#9]. TBAs were considered an asset to PVT when providing referrals [#20,33,36] but a barrier when conducting unsanctioned home births [#16,27]. TBAs were found to be effective when training, supervision, and referral systems were in place [#20,27].

Ability

Ability challenges occurred at the health worker and health facility levels and tended to be less frequently reported in studies conducted in 2007 and later. The most frequently reported challenges occurred at the health facility and were PVT training identified as inadequate due to its incompatibility with training needs or irregular delivery [#3–5,7–10,12,14–18,21–25,29,32,33,35–37,43,44,47] followed by delivery of inconsistent IYCF messages [#1,2,4,6,7,9,10,14,15,17,18,20,21,23,25,28,35–37,40]. Poor supervision [#5,8,9,12,22,24,30,35–38,43,44], including lack of feedback on performance, was a health facility barrier that was reported slightly more frequently among later studies.

At the health worker level, low knowledge of HIV transmission paths [#2–4,9,14,17,18,36] and poor self-efficacy in diagnosing or counseling patients on HIV [#3,8,9,14] decreased in reported frequency in studies conducted 2007 and after.

Facilitators to delivery of PVT services

Facilitators were reported in lower frequencies than barriers and tended to be resolutions (Table 3). Health workers were frequently intrinsically motivated by effecting behavior change and saving lives [#1,4,7–9,12,15,25,45] and less frequently motivated by salary [#30,38], others valuing their work [#21], or professional opportunities [#30].

Facilitators to health workers’ ability to provide care included confidence regarding HIV transmission knowledge (health worker level [#34,36,37]) and appropriate training (health facility level [#5,13,15,22,38,45]). Opportunity facilitators at the work level included improvements to record systems [#5,8,24,26], and those at the health facility included consistent supplies [#13,24,36,45] and facility updates [#13,15,26] as well as quality supervision [#5,13,26,30]. Integration of PVT services [#15,23,38] and NGO’s technical [#2,15,21,23,44] and financial support [#14,21,45] were facilitators at the administrative level.

Lay and community-based health worker cadres were found to contribute to improved quality and quantity of PVT services [#6,8,9,21,33,38,44]. For example, lay health workers contributed to decreased drop-off of women in the beginning of the PVT cascade [#6], workload for skilled health workers, and HIV stigmatization in the community [#9]. CHWs facilitated PVT through conducting community HIV education [#6,8], leading support groups for HIV-infected women [#8,21,23], and recovering patients considered lost to follow-up [#21].

Discussion

This theoretically-driven synthesis of 47 studies evaluating PVT service delivery has made it clear that focusing predominantly on the individual-level factors of motivation, knowledge, and self-efficacy, while necessary, is not sufficient to improve delivery of PVT services. The more frequent reporting of barriers and facilitators to intrinsic motivation compared to extrinsic suggests the relative importance of intrinsic motivation to health workers in low-resource settings. Challenges to knowledge and self-efficacy were generally reported less frequently in 2007 and later, potentially reflecting the increased experience of workers in delivering PVT services, effectiveness of early ability-focused interventions, or changes in study objectives over time. Conversely, challenges in the patient, work, and administrative levels were reported slightly more frequently in studies conducted 2007 onwards.

Systematic inquiry is grounded in robust theory, which leads to advancement of knowledge and practice (Friedman, 2003). The absence of theoretical guidance in the majority of studies under review suggests a gap in the regular application of recognized theoretical perspectives in studies focusing on health workers in context of PVT.

The novel integration of the MOA with the Determinants of Performance framework identified the domains affecting performance within each ecological level of a health worker’s delivery of PVT services. The most frequently reported challenges coalesced in the health facility and spanned all three MOA domains. Seven barriers were reported in over 30% of studies; one each at the health worker (motivation), patient (opportunity), and work level (opportunity), and four at the health facility (two opportunity, two ability).

The majority of challenges occurred within the opportunity domain. Although addressing these numerous and complex contextual challenges is difficult in the face of severe resource constraints, this strategy has potential to mitigate challenges in other domains. For example, motivation is a complex construct influenced by health workers’ own abilities as well as organizational, patient, community, and cultural contexts (Franco et al., 2002). Thus, an approach that incorporates the facility, administrative, and political-economic environments will impact motivation and ability as well.

Implementation science is one such approach that holds promise to close the gaps that result in infant and young child HIV infection. Implementation science systematically incorporates contextual factors across ecological levels into study design and evaluation (Sturke et al., 2014). This has already provided insights into the need for increased focus on administrative factors of leadership, management, and funding (Edwards & Barker, 2014), and interventions using iterative, systems-view approaches have potential to reduce patient drop-off along the PVT cascade (Sherr et al., 2014). Thus, we suggest incorporating implementation science principles into research on delivery of PVT services to more effectively identify and address opportunity challenges.

This review characterized serious bi-directional challenges at the point of care that are influenced by sociocultural trends. Respectful consideration of patients’ needs was lacking in one-fifth of studies [#1,8,10,16,21,27,31,40,47]. Documented in maternal healthcare generally (Silal, Penn-Kekana, Harris, Birch, & McIntyre, 2012), this is even more problematic considering the stigma, gender, and socioeconomic vulnerabilities associated with HIV (Ramjee & Daniels, 2013). Furthermore, two studies reported maternal compliance within the PVT cascade was portrayed as a means for preservation of her child’s health [#1,45], contrary to the known benefits of treating a woman for her own sake (Marazzi et al., 2011; UNAIDS, 2014).

These factors may influence patients’ hiding of noncompliant behaviors, which could circumvent women’s opportunity to receive appropriate care. For example, fear and psychological distress following an HIV-positive diagnosis influenced women’s refusal of HIV testing [#10,14,15,41,46] and the hiding of HIV-infected status later in care [#1,27,33–36,38,43–45,47]. Stigma alone has been shown to impact women’s drop-off at every step of the PVT cascade (Turan & Nyblade, 2013). Thus, we propose that practices to mitigate stigma and respectfully approach women should be incorporated into PVT delivery interventions.

Engaging community-based health workers in delivery of PVT was one such strategy found to be effective in this review. Early community health worker engagement increases enrollment of HIV-exposed and -infected infants and young children in care (Ahmed et al., 2015) and positively influences exclusive breastfeeding and child growth (Tomlinson et al., 2014). However, this review found lay and community-based health workers’ to have unclear status and roles, which can lead to health workers performing tasks outside their training or not living up to expectations. Thus, clear job descriptions, supportive supervisory structures, and formal recognition in the health system are necessary in order to capitalize on these benefits of community-based and lay health workers.

Lessons learned

This comprehensive literature review used two popular databases and generated a strong number of studies for inclusion. While this review has captured published reports likely reflective of non-peer-reviewed material, there is potential for missed information in organizational reports and documents.

The Determinants of Performance framework was proposed as a research agenda for interventions. Thus, it includes most but perhaps not all potential ecological levels (e.g. sociocultural factors).

Differences in study objectives and methodologies across our 47 articles may have limited the factors reported. For example, the low reported frequency of administrative and political-economic factors may be reflective, in part, of study objectives focusing on more proximal factors. However, this does not mean those factors were not salient, rather perhaps they were not probed (Gourlay et al., 2013). Similar caution should be applied to interpretation of our findings across time groupings.

Finally, community-based health workers were under-represented in our review, which was surprising given their widespread involvement in the PVT cascade. This may reflect their more recent integration into health systems or a gap in research about their experiences. With current global focus on their potential, continued evaluation of community-based health workers is necessary.

Conclusions

To eliminate vertical transmission of HIV, interventions need to address the multiple ecological levels and contextual factors involved in delivery of PVT services. Individual health worker level barriers may be decreasing. Thus, a focus shift to factors at the health facility and administrative environments holds promise for far-reaching impact, as does meaningful integration of community-based health workers into the health system. Both facility- and community-based health workers have a role to play in respectfully engaging and retaining women in PVT care and reducing surrounding stigma. Incorporation of implementation science principles into research on delivery of PVT services can illuminate structural opportunity challenges and pathways through which to address them. Research seeking to strengthen the delivery of PVT services should incorporate theory to address factors beyond the individual’s motivation and ability when assessing health workers’ barriers and facilitators.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Sarah Young, the Health Science and Policy Librarian at Cornell University’s Mann Library, for her guidance in comprehensive review methodology. We recognize Yeri Son and Jacquelyn Rivera for their work in conducting a preliminary literature review. Finally, we appreciate the insightful comments from the anonymous reviewers of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Rawlings Cornell Presidential Research Scholarship (DEM) and the National Institute of Mental Health under K01 MH098902 (SLY).

Contributor Information

Roseanne C. Schuster, Email: rcs346@cornell.edu, Program in International Nutrition, Division of Nutritional Sciences, Cornell University, 116 Savage Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853, 716-861-3947.

Devon E. McMahon, Email: dem287@cornell.edu, Division of Nutritional Sciences, Cornell University, 116 Savage Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853, 646-942-3429.

Sera L. Young, Email: sera.young@cornell.edu, Program in International Nutrition, Division of Nutritional Sciences, Cornell University, 113 Savage Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853, 607-255-4647.

References

- Agadjanian V, Hayford SR. PMTCT, HAART, and childbearing in Mozambique: an institutional perspective. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(S1):103–112. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9535-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S, Kim MH, Dave AC, Sabelli R, Kanjelo K, Preidis GA, et al. Improved identification and enrolment into care of HIV-exposed and -infected infants and children following a community health worker intervention in Lilongwe, Malawi. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2015;18(1) doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.1.19305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asefa A, Mitike G. Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission (PMTCT) of HIV services in Adama town, Ethiopia: clients’ satisfaction and challenges experienced by service providers. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2014;14:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg M, Pringle CD. The Missing Opportunity in Organizational Research: Some Implications for a Theory of Work Performance. Academy of Management Review. 1982;7(4):560–569. doi: 10.5465/AMR.1982.4285240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau JW, Hopp W, McClain JO, Thomas LJ. On the interface between operations and human resources management. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University, School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Center for Advanced Human Resource Studies; 2002. pp. 1–41. (No. CAHRS Working Paper #02-22) [Google Scholar]

- Buskens I, Jaffe A. Demotivating infant feeding counselling encounters in southern Africa: do counsellors need more or different training? AIDS Care. 2008;20(3):337–345. doi: 10.1080/09540120701660346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan M, Ford N, Schneider H. A systematic review of task-shifting for HIV treatment and care in Africa. Human Resources for Health. 2010;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasela CS, Hudgens MG, Jamieson DJ, Kayira D, Hosseinipour MC, Kourtis AP, et al. Maternal or infant antiretroviral drugs to reduce HIV-1 transmission. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362(24):2271–2281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0911486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi BH, Stringer JSA, Moodley D. Antiretroviral drug regimens to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV: a review of scientific, program, and policy advances for Sub-Saharan Africa. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2013;10(2):124–133. doi: 10.1007/s11904-013-0154-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinkonde JR, Sundby J, de Paoli M, Thorsen VC. The difficulty with responding to policy changes for HIV and infant feeding in Malawi. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2010;5(1):11. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra M, Rollins N. Infant feeding in the time of HIV: rapid assessment of infant feeding policy and programmes in four African countries scaling up prevention of mother to child transmission programmes. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2008;93(4):288–291. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.096321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creek T, Ntumy R, Mazhani L, Moore J, Smith M, Han G, et al. Factors associated with low early uptake of a national program to prevent mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT): results of a survey of mothers and providers, Botswana, 2003. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;13(2):356–364. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Paoli MM, Manongi R, Klepp KI. Counsellors’ perspectives on antenatal HIV testing and infant feeding dilemmas facing women with HIV in northern Tanzania. Reproductive Health Matters. 2002;10(20):144–156. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(02)00088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delva W, Draper B, Temmerman M. Implementation of single-dose nevirapine for prevention of MTCT of HIV -lessons from Cape Town. Southern African Medical Journal. 2006;96(8):706, 708–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickin KL, Dollahite JS, Habicht JP. Enhancing the intrinsic work motivation of community nutrition educators: how supportive supervision and job design foster autonomy. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2011;34(3):260–273. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e31821dc63b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty TM, McCoy D, Donohue S. Health system constraints to optimal coverage of the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission programme in South Africa: lessons from the implementation of the national pilot programme. African Health Sciences. 2005;5(3):213–218. doi: 10.5555/afhs.2005.5.3.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty T, Chopra M, Nsibande D, Mngoma D. Improving the coverage of the PMTCT programme through a participatory quality improvement intervention in South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):406. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards N, Barker PM. The importance of context in implementation research. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2014;67(Suppl 2):S157–62. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadnes LT, Engebretsen I, Moland K, Nankunda J, Tumwine JK, Tylleskär T. Infant feeding counselling in Uganda in a changing environment with focus on the general population and HIV-positive mothers - a mixed method approach. BMC Health Services Research. 2010;10:260. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falnes EF, Moland KM, Tylleskär T, de Paoli MM, Msuya SE, Engebretsen IM. “It is her responsibility”: partner involvement in prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV programmes, northern Tanzania. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2011;14:21. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-14-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco LM, Bennett S, Kanfer R. Health sector reform and public sector health worker motivation: a conceptual framework. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 2002;54(8):1255–1266. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman K. Theory construction in design research: criteria: approaches, and methods. Design Studies. 2003;24(6):507–522. doi: 10.1016/S0142-694X(03)00039-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geelhoed D, Lafort Y, Chissale L, Candrinho B, Degomme O. Integrated maternal and child health services in Mozambique: structural health system limitations overshadow its effect on follow-up of HIV-exposed infants. BMC Health Services Research. 2013;13:207. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourlay A, Birdthistle I, Mburu G, Iorpenda K, Wringe A. Barriers and facilitating factors to the uptake of antiretroviral drugs for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2013;16(1) doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamela G, Kabondo C, Tembo T, Zimba C, Kamanga E, Mofolo I, et al. Evaluating the benefits of incorporating traditional birth attendants in HIV prevention of mother to child transmission service delivery in Lilongwe, Malawi. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2014;18(1):27–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- hIarlaithe MO, Grede N, de Pee S, Bloem M. Economic and social factors are some of the most common barriers preventing women from accessing maternal and newborn child health (MNCH) and prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) services: a literature review. AIDS and Behavior. 2014;18(Suppl 5):S516–30. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0756-5. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0756-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwood C, Haskins L, Vermaak K. Prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) programme in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: an evaluation of PMTCT implementation and integration into routine maternal, child and women’s health services. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2010a:992–999. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwood C, Voce A, Vermaak K, Rollins N, Qazi S. Routine checks for hiv in children attending primary health care facilities in South Africa: attitudes of nurses and child caregivers. Social Science & Medicine. 2010b;70(2):313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel-Ballard K, Waithaka M, Greiner T. Infant feeding counselling of HIV-infected women in two areas in Kenya in 2008. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2014;25(13):921–928. doi: 10.1177/0956462414526574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YM, Banda J, Hiner C, Tholandi M, Bazant E, Sarkar S, et al. Assessing the quality of HIV/AIDS services at military health facilities in Zambia. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2013;24(5):365–370. doi: 10.1177/0956462412472811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok MC, Dieleman M, Taegtmeyer M, Broerse JE, Kane SS, Ormel H, et al. Which intervention design factors influence performance of community health workers in low- and middle-income countries? A systematic review. Health Policy and Planning. 2014 doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu126. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwapong GD, Boateng D, Agyei-Baffour P, Addy EA. Health service barriers to HIV testing and counseling among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic; a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Services Research. 2014;14:267. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labhardt ND, Manga E, Ndam M, Balo JR, Bischoff A, Stoll B. Early assessment of the implementation of a national programme for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Cameroon and the effects of staff training: a survey in 70 rural health care facilities. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2009;14(3):288–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledikwe JH, Kejelepula M, Maupo K, Sebetso S, Thekiso M, Smith M, et al. Evaluation of a well-established task-shifting initiative: the lay counselor cadre in Botswana. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e61601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshabari SC, Blystad A, de Paoli M, Moland KM. HIV and infant feeding counselling: challenges faced by nurse-counsellors in northern Tanzania. Human Resources for Health. 2007;5(1):18. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-5-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy JM. Women’s expectations of treatment and care after an antenatal HIV diagnosis in Lilongwe, Malawi. Reproductive Health Matters. 2009;17(33):152–161. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(09)33436-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann QK, Mofolo I, Bobrow E, Maida A, Kamanga E, Pagadala N, et al. Exploring the feasibility of engaging traditional birth attendants in a prevention of mother to child HIV transmission program in Lilongwe, Malawi. Malawi Medical Journal. 2012;24(4):79–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke EA, Latham GP. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: a 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist. 2002;57(9):705–717. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.57.9.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malema RN, Malaka DW, Mothiba TM. Experiences of lay counsellors who provide VCT for PMTCT of HIV and AIDS in the Capricorn District, Limpopo Province. Curationis. 2010;33(3):15–23. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v33i3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marazzi MC, Palombi L, Nielsen-Saines K, Haswell J, Zimba I, Magid NA, et al. Extended antenatal use of triple antiretroviral therapy for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 correlates with favorable pregnancy outcomes. Aids. 2011;25(13):1611–1618. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283493ed0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazia G, Narayanan I, Warren C, Mahdi M, Chibuye P, Walligo A, et al. Integrating quality postnatal care into PMTCT in Swaziland. Global Public Health. 2009;4(3):253–270. doi: 10.1080/17441690902769669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medley AM, Kennedy CE. Provider challenges in implementing antenatal provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling programs in Uganda. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2010;22(2):87–99. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.2.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mnyani CN, McIntyre JA. Challenges to delivering quality care in a prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV programme in Soweto. Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine. 2013;14(2):64–69. doi: 10.4102/hivmed.v14i2.80. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mwai GW, Mburu G, Torpey K, Frost P, Ford N, Seeley J. Role and outcomes of community health workers in HIV care in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2013;16(1) doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimoli JF, Frymus DE, Wuliji T, Franco LM, Newsome MH. A Community Health Worker “logic model”: towards a theory of enhanced performance in low- and middle-income countries. 2014;12:56. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-12-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuwagaba-Biribonwoha H, Mayon-White RT, Okong P, Carpenter LM. Challenges faced by health workers in implementing the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT) programme in Uganda. Journal of Public Health. 2007;29(3):269–274. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdm025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okello DRO, Gilson L. Exploring the influence of trust relationships on motivation in the health sector: a systematic review. Human Resources for Health. 2015;13:16. doi: 10.1186/s12960-015-0007-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Phaswana-Mafuya N, Ladzani R. Implementation of the national programme for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: a rapid assessment in Cacadu district, South Africa. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2010;9(1):95–106. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2010.484594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez F, Aung K, Ndoro T, Engelsmann B, Dabis F. Participation of traditional birth attendants in prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV services in two rural districts in Zimbabwe: a feasibility study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):401. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piwoz EG, Ferguson Y, Bentley ME, Corneli AL, Moses A, Nkhoma J, et al. Differences between international recommendations on breastfeeding in the presence of HIV and the attitudes and counselling messages of health workers in Lilongwe, Malawi. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2006;1:2. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramjee G, Daniels B. Women and HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Research and Therapy. 2013;10:30. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-10-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rispel LC, Peltzer K, Phaswana-Mafuya N, Metcalf CA, Treger L. Assessing missed opportunities for the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission in an Eastern Cape local service area. South African M=Medical Journal. 2009;99(3):174–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe AK, de Savigny D, Lanata CF, Victora CG. How can we achieve and maintain high-quality performance of health workers in low-resource settings? The Lancet. 2005;366(9490):1026–1035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rujumba J, Tumwine JK, Tylleskär T, Neema S, Heggenhougen HK. Listening to health workers: lessons from eastern Uganda for strengthening the programme for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. BMC Health Services Research. 2012;12:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist. 2000;55(1):68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarker M, Papy J, Traore S, Neuhann F. Insights on HIV pre-test counseling following scaling-up of PMTCT program in rural health posts, Burkina Faso. East African Journal of Public Health. 2009;6(3):283–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S. Breastfeeding knowledge among health workers in rural South Africa. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 2005;51(1):33–38. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmh071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shayo EH, Mboera LE, Blystad A. Stakeholders’ participation in planning and priority setting in the context of a decentralised health care system: the case of prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV programme in Tanzania. BMC Health Services Research. 2013;13:273. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr K, Gimbel S, Rustagi A, Nduati R, Cuembelo F, Farquhar C, et al. Systems analysis and improvement to optimize pMTCT (SAIA): a cluster randomized trial. 2014;9:55. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemsen E, Roth A, Balasubramanian S. How motivation, opportunity, and ability drive knowledge sharing: The constraining-factor model. Journal of Operations Management. 2008;26(3):426–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jom.2007.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silal SP, Penn-Kekana L, Harris B, Birch S, McIntyre D. Exploring inequalities in access to and use of maternal health services in South Africa. BMC Health Services Research. 2012;12:120. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simba D, Kamwela J, Mpembeni R, Msamanga G. The impact of scaling-up prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV infection on the human resource requirement: the need to go beyond numbers. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2008;25:17–29. doi: 10.1002/hpm.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague C, Chersich MF, Black V. Health system weaknesses constrain access to PMTCT and maternal HIV services in South Africa: a qualitative enquiry. AIDS Research and Therapy. 2011;8:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson K, Myer L. Barriers to initiating antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy: a qualitative study of women attending services in Cape Town, South Africa. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2012;11(1):65–73. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2012.671263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturke R, Harmston C, Simonds RJ, Mofenson LM, Siberry GK, Watts H, et al. A Multi-Disciplinary Approach to Implementation Science: The NIH-PEPFAR PMTCT Implementation Science Alliance. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2014;67(Suppl2):S163–67. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson M, Doherty T, Ijumba P, Jackson D, Lawn J, Persson LA, et al. Goodstart: a cluster randomised effectiveness trial of an integrated, community-based package for maternal and newborn care, with prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in a South African township. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2014;19(3):256–266. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan JM, Nyblade L. HIV-related Stigma as a Barrier to Achievement of Global PMTCT and Maternal Health Goals: A Review of the Evidence. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(7):2528–2539. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0446-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan JM, Hatcher AH, Medema-Wijnveen J, Onono M, Miller S, Bukusi EA, et al. The role of HIV-related stigma in utilization of skilled childbirth services in rural Kenya: a prospective mixed-methods study. PLos Medicine. 2012;9(8):e1001295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuthill E, McGrath J, Young SL. Commonalities and differences in infant feeding attitudes and practices in the context of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a metasynthesis. AIDS Care. 2013;26(2):214–225. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.813625. http://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2013.813625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. THE GAP REPORT. Geneva: 2014. pp. 1–422. [Google Scholar]

- Uwimana J, Jackson D, Hausler H, Zarowsky C. Health system barriers to implementation of collaborative TB and HIV activities including prevention of mother to child transmission in South Africa. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2012a;17(5):658–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.02956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uwimana J, Zarowsky C, Hausler H, Jackson D. Engagement of non-government organisations and community care workers in collaborative TB/HIV activities including prevention of mother to child transmission in South Africa: opportunities and challenges. BMC Health Services Research. 2012b;12:233. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernooij E, Hardon A. What mother wouldn’t want to save her baby?” HIV testing and counselling practices in a rural Ugandan antenatal clinic. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2013;15(sup4):S553–S566. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.758314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanyu B, Diom E, Mitchell P, Tih P, Meyer D. Birth attendants trained in “prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission” provide care in rural Cameroon, Africa. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2007;52(4):334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson-Jones D, Balira R, Ross DA, Weiss HA, Mabey D. Missed opportunities: poor linkage into ongoing care for HIV-positive pregnant women in Mwanza, Tanzania. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e40091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040091.t003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants in resource-limited settings: towards universal access. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. pp. 1–89. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. HIV and infant feeding. Geneva: 2007. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Consolidated guidelines on general HIV care and the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach. 2013:269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Task shifting: rational redistribution of tasks among health workforce teams. Geneva: 2008. pp. 1–96. [Google Scholar]

- Yeap AD, Hamilton R, Charalambous S, Dwadwa T, Churchyard GJ, Geissler PW, Grant AD. Factors influencing uptake of HIV care and treatment among children in South Africa – a qualitative study of caregivers and clinic staff. AIDS Care. 2010;22(9):1101–1107. doi: 10.1080/0954012100360221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.