Abstract

Objectives

We conducted a pilot study of a sleep health promotion program for college students. The aims of the study were to 1) determine the feasibility of the program, and 2) explore changes in sleep knowledge and sleep diary parameters.

Design

Open trial of a sleep health promotion program for college students.

Setting

A small liberal arts university in southwestern Pennsylvania

Participants

University students (primarily female).

Intervention

Active intervention components included individualized email feedback based on each participant’s baseline sleep diary and an in-person, group format presentation on sleep health.

Measurements

Participants completed online questionnaires and sleep diaries before and after the health promotion intervention. Online questionnaires focused on sleep knowledge and attitudes toward sleep, as well as Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) sleep and psychosocial assessments.

Results

Of participants who completed some aspect of the study, 89% completed at least one intervention component (in-person lecture and/or sleep diary). Participants reported significant improvement in sleep knowledge and changes in sleep diary parameters (decreased sleep onset latency and time spent in bed, resulting in greater sleep efficiency). Sleep duration also increased by 30 minutes among short sleepers who obtained <7 hours sleep at baseline.

Conclusions

Preliminary evaluation of a brief program to promote sleep health suggests that it is feasible and acceptable to implement, and that it can favorably alter sleep knowledge and behaviors reported on the sleep diary in college students. Controlled trials are warranted.

Keywords: normative sleep, health promotion, health education, mental health

Introduction

Sleep and circadian functioning are essential to good health (1), and undergo dramatic changes in adolescence and during the transition to college. During adolescence, normative biological changes are accompanied by psychosocial and environmental changes, including increasing autonomy and reduced parental involvement, growing role of peers, increasing academic demands, substance use (including evening intake of alcohol and stimulants such as caffeine), and pervasive use of technology (2–5).The combination of biological and social/environmental influences leads to delayed sleep times, weekend oversleep, and restricted sleep. Bedtimes become further delayed in first year college students as compared to high school seniors (6).

Disturbed and insufficient sleep is prevalent among college students. In one report, college students reported obtaining an average of 7 hours of sleep across the week (6), which is at the lowest end of the 7 or greater hours recommended for young adults (7;8), and 25% obtained less than 6.5 hours of sleep per night (6). Only 34% of students reported good sleep quality (i.e., <5 on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (9)) and 25% reported significant levels of daytime sleepiness (6). In another sample of undergraduates, three-quarters endorsed daytime sleepiness and nearly half reported fatigue, motivation problems, and concentration or memory difficulties (10). In addition, insufficient sleep and sleep disorders among college students have been associated with important functional and health consequences (5), including lower grades (11–13), falling asleep while driving (14), lower mood, and more depressive symptoms (15;16).

Fortunately, increasing total sleep time among college students is associated with reduced sleepiness and fatigue, and improved attention, reaction time, mood, and measures of athletic performance (17;18). Thus, recent efforts have concentrated on developing and testing sleep-health promotion programs for this population, many of which have focused on sleep education. Broad-based sleep education dissemination approaches have the benefit of providing all students a chance to be informed about sleep and its role in learning and physical and mental health, and, for those with sleep disorders, to gather needed information to make appropriate referrals (19).

Recently developed programs aiming to improve sleep health among college students have shown preliminary success in altering sleep knowledge and sleep habits. Various formats include psychology courses supplemented with sleep-specific instruction; an email-based self-help sleep health promotion program; and a sleep education program delivered via classroom lecture, web-based self-learning, and interactive classroom discussion (20–23). While relatively little work in this area has been conducted in college student samples, much more work has examined the impact of sleep education programs among younger adolescents (24–30). Participation in nearly all of these sleep education programs has been associated with an increase in knowledge about sleep, but changes in sleep parameters as a result of the program have been less consistent. Research has suggested that individualized feedback may be effective in promoting health behavior change (such as reducing substance use) because it makes explicit each individual’s behavior and acts as a source of social comparison to motivate reevaluation of the behavior (31–33). Moreover, a unique meta-analysis has shown that tailored health behavior change interventions are effective in stimulating health behavior change (34). Recording sleep habits via daily diary and offering individualized feedback may improve sleep habits because of the enhanced awareness of sleep patterns when compared to other similar individuals. To our knowledge, however, no existing sleep programs have provided individualized feedback to participants based on their self-reported sleep patterns. There have, however, been calls for improving the effectiveness of sleep health promotion programs by including individual tailoring of feedback, use of techniques to increase motivation to change, and program delivery via the internet (35).

We conducted a pilot study of a sleep health promotion program for college students. The program consisted of two core components that we hypothesized would lead to improved sleep health behaviors: (1) packaging current research evidence on a health issue that is relevant and meaningful to the population of interest (delivered via an in-person presentation on sleep health), and (2) tailoring feedback for each participant on his or her actual sleep patterns as reported on the sleep diary to increase participants’ knowledge about their specific sleep behaviors (delivered via individualized email feedback based on sleep diary records). Drawing on Theory of Planned Behavior and Social Cognitive Theory (36–38), the intervention provided opportunities for college students to increase their self-efficacy related to sleep health and to shift their perceived control over sleep-related behaviors, as well as calibrate themselves against their peers. Because the factors that affect sleep are likely to be unique to each individual, we presented information on a range of factors regarding the importance of sleep and the consequences of insufficient sleep that we believed to be relevant to this population. Similarly, we used technology (35) to feasibly deliver personalized information regarding their actual sleep patterns as reported on the sleep diary, as well as to provide the opportunity to compare one’s own behavior to similar individuals (e.g., knowing that one’s peers obtain more sleep at night may motivate modification of sleep behavior). The aims of the study were to 1) determine the feasibility of the program and to 2) examine changes in sleep knowledge and sleep diary parameters.

Methods

Overall Design and Participants

In this pilot sleep health promotion project, we provided a didactic presentation to disseminate the latest research on sleep health to college students, with personalized feedback to participants regarding their own sleep based on a daily sleep diary completed for the week prior to the didactic presentation. Pre-post assessments evaluated sleep knowledge, sleep diary outcomes, and changes in psychosocial function that were associated with completion of the program. A total of 110 participants completed at least one aspect of this study, with completion rates described below.

Students attending a small liberal arts university in southwestern Pennsylvania were recruited for this pilot study during the Spring 2014 semester. They were recruited over a two week period via advertising the study through the student Health Services Center, Resident Assistants, on-campus recruitment by study staff members in high student traffic areas (i.e., near the dining hall), and word of mouth. The sample was nearly entirely female (96.4%), reflecting the gender composition of this formerly all-women’s University. Any student enrolled at the University and who was at least 18 years old was eligible to participate. While the majority of participants (n=108, 98.2%) were full-time undergraduates between the ages of 18–22, the upper age range was 50.5 years, and the sample included a small proportion of part-time undergraduate students (n=2, 1.8%). See Supplemental Table 1 (S1) for further participant characteristics.

Procedures

The study consisted of two main components over a one-month span in the spring semester—a sleep diary and a sleep health presentation—as well as psychosocial assessments completed at baseline and after completion of the second sleep diary.

During a two-week recruitment period, interested students were directed to a study website, where the study was explained in detail and electronic informed consent was obtained. During Week 1 of the actual study, consented participants were invited to complete a demographic survey and other baseline questionnaires.

During Week 2, participants completed an on-line daily sleep diary. Each evening and morning for one week, participants answered questions related to sleep timing, sleep continuity, the occurrence of naps, and the number of text messages received and read before sleep. Daily reminders to complete the diary were sent via email.

During the first half of Week 3, participants attended an hour-long presentation on sleep health, which was followed by discussion and questions. The presentation was offered in a large group format on four separate occasions during the first half of this week, and it was given by one of the study investigators (P.L. Franzen). Besides conceptualizing sleep health and providing recommendations to improve sleep health (see Table 1), the presentation was intended to provide evidence for the role of sleep in promoting health from experimental and epidemiological studies. Some of this content was specifically selected to be relevant to college students (e.g., impact of sleep on academic performance, weight, and social interactions) to target motivation to change sleep behaviors.

Table 1.

Components reviewed in the in-person sleep education presentation on sleep health.

| Presentation Components |

|---|

|

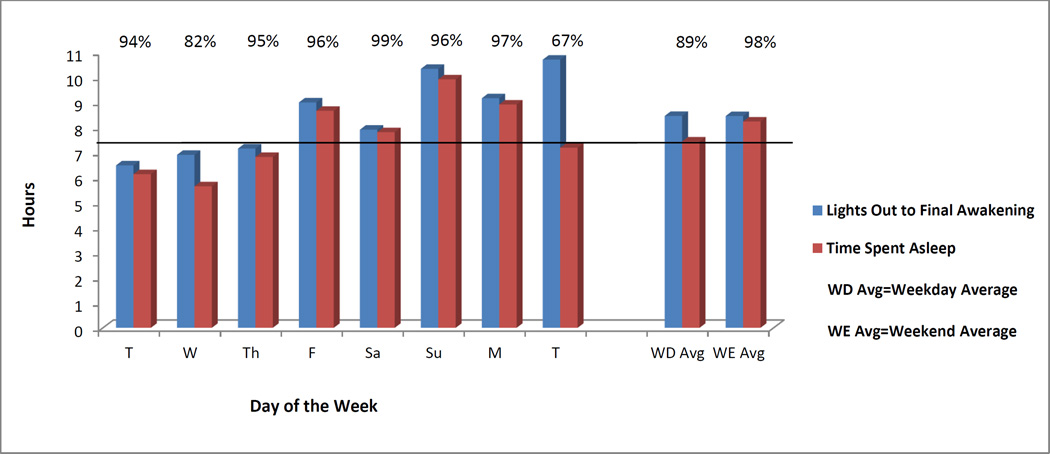

Individualized feedback was provided to each participant via email within one day of attending the lecture, and contained a summary of each participant’s sleep diary data collected over the baseline week. The email contained a graphical display (Figure 1) of daily total time spent in bed and spent asleep, as well as sleep efficiency (the ratio of total sleep time to total time in bed), and also included weekday and weekend averages of these variables for each participant. All participants also received several paragraphs of text outlining best sleep practices that followed the RU SATED framework (1) and reinforced the material covered in the in-person presentation on sleep health (e.g., that most people feel best sleeping between 7 and 9 hours each night, while also achieving a sleep efficiency > 90%; the importance of consistency of sleep schedules, especially wake up time, and avoiding long oversleep on weekends). To help participants compare their sleep to others, we provided histograms of individuals’ average sleep duration and sleep efficiency from 18 to 25 year olds who participated in other sleep research studies at the University of Pittsburgh who had at least 7 days of sleep diary data.

Figure 1.

An example of the graphical display of weekly individualized sleep diary feedback reports that were emailed to participants during the week they attended the sleep health lecture, as well as at the end of their participation in the study. The graphs depicted a participant’s reported daily hours spent in bed, time spent asleep, and sleep efficiency (% provided on the bottom of the bars), as well as averages of these variables on weekdays (WD) and weekends (WE).

Beginning on Thursday of Week 3, participants had a short break from school through the following Monday (Easter Break, a span of 5 calendar days). Beginning Monday evening, participants completed another week-long sleep diary (i.e., the Tuesday morning diary reflected night before, which was the first night of sleep since returning after break and the first night of our post-intervention sleep diary). Classes resumed Tuesday morning. After completing this second week-long diary, participants then repeated the online questionnaire battery and program evaluation questions, which assessed the first full week after the Easter Break. Completion of the online questionnaire battery occurred during the penultimate week before end-of-the-semester finals. At this point, no further data was collected from participants. We did, however, have two further contacts via email with participants after this period. One email included graphical feedback on their sleep diary, with separate graphs depicting the participant’s pre- and post-intervention sleep diaries (as detailed above), as well as the total sleep time and sleep efficiency histograms from the study population to enable them to compare themselves to peers who were also in the study; accompanying text reiterated the principles regarding healthy sleep (as described above). A final email was then sent to participants that included a report of their baseline Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) scores for various sleep and psychosocial assessments (generated via Assessment Center). The report consists of the participant’s standard score on each domain along with how that compares to the general population, individuals in the same age range, and individuals of the same gender, along with a graph of the participants’ standardized scores (see (39) for an example of this report). The email also included phone numbers to call if they had any questions or concerns and the reports or the study, and also included referral information if they had concerns about any symptoms they may be experiencing.

Participants were compensated up to $50 for completing the entire study ($10 for each: baseline questionnaires, baseline sleep diary, attending the presentation, post-intervention questionnaires, and follow-up sleep diary). Compensation for the sleep diaries required completing at least 75% of the morning and evening entries. An additional $50 and $100 gift cards were raffled off to each group who attended one of the in-person sleep health presentations.

All study procedures received Institutional Review Board approval.

Measures

Feasibility was measured by enrollment and completion rates. Our initial goal was to enroll at least 80 participants, which was exceeded. We expected that at least 80% of the enrolled participants would complete at least one intervention component (attend lecture and/or complete sleep diary).

Participants completed the following self-report measures via a secured online assessment website.

A brief demographic survey included age, sex, race, marital status, education level, GPA, Quality Point Average (QPA), income, height, weight, student status, and employment status.

The 20-item Sleep Beliefs Scale (SBS) assessed sleep knowledge by asking participants to rate whether specific behaviors have a positive, negative, or neutral effect on sleep (40). Each answer records the participant’s belief about the effect of each behavior on sleep in general (rather than the participant’s specific experience). For example, one question asks about the effect of drinking coffee after dinner on sleep, asking participants whether this behavior has a positive, negative, or neutral effect. Participants answer each item correctly if they choose a negative effect for all but 4 items, which have a positive effect. This scale was highly relevant to the didactic material presented in the lecture. Selected items of the Sleep Practices and Attitudes Questionnaire (SPAQ; 41) were used to measure attitudes and beliefs about sleep (see Appendix A), and included items focused on: (1) importance of sleep in various age groups; (2) importance of sleep to overall health; and (3) sleep-related knowledge. The importance of sleep to various age groups and the importance of sleep to health subscales both have ranges of 1–4, with lower scores indicate greater importance. The sleep knowledge subscale has a range of 1–5, with lower scores indicating greater sleep-related knowledge. Because participants completed a subset of items from the original version of the SPAQ, we conducted reliability analyses to examine the internal consistency of the items in each of these three domains at both pre- and post-lecture (Cronbach’s alpha between 0.67–0.87).

A web-based version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Diary (42) consisted of items completed in the evening and in the morning pertaining to daytime and nighttime sleep behaviors.

Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) scales included sleep disturbance, sleep-related impairments, fatigue, anxiety, depression, anger, emotional support, social isolation, satisfaction in social roles, and satisfaction in discretionary social activities, using a 7 day recall period. The Computerized Adaptive Testing (CAT) format uses individual responses to guide selection of subsequent questions, until the individual’s score can be estimated with a specified level of precision (43;44). CAT requires fewer overall questions to determine an individual’s score on a given scale. Raw scores on these measures are standardized into T-scores, with a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10 on each measure, with higher numbers reflecting higher amounts of the scale. Previous work has described the development and psychometric testing of each PROMIS measure we utilized among individuals age 18 and older (45–50). CAT PROMIS assessments were completed on-line via the Assessment Center (https://www.assessmentcenter.net/).

Following all program activities, participants evaluated the program using a 10-item questionnaire (see Table 2), with items rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). We also collected anonymous feedback from participants attending the lecture on their satisfaction with the presentation on sleep health using a 5-item questionnaire (see Table 2), using the same 5-point Likert scale.

Table 2.

Evaluation of participant satisfaction with the program and the sleep health lecture, by items rated on a 5-point Likert Scale (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree).

| Program Satisfaction Evaluation Item | Mean (S.D.) n=88 |

|---|---|

| I was satisfied overall with the program | 4.06 (0.67) |

| I would recommend participating in this program to a friend | 4.33 (0.72) |

| The program has helped me to improve my sleep health | 3.16 (0.81) |

| The program has helped me to improve my overall health | 3.02 (0.80) |

| The online sleep diary was easy to use | 4.08 (0.93) |

| The online diary was user-friendly | 4.15 (0.84) |

| The report about my sleep patterns was useful | 3.74 (0.97) |

| The presentation on sleep was informative | 4.16 (0.84) |

| The presentation on sleep was relevant to my life | 4.06 (0.88) |

| The study web site was easy to use | 4.23 (0.85) |

| Lecture Satisfaction Evaluation Item | n=87 |

| I enjoyed the educational session | 3.90 (0.76) |

| I am likely to make some changes around sleep based on this presentation | 3.83 (0.90) |

| The presentation speaker was interesting | 4.21 (0.82) |

| The presentation content was useful | 4.33 (0.69) |

Data Analysis

Among participants who completed the active intervention components (baseline sleep diary and attending the lecture), we examined baseline to post-intervention changes in sleep knowledge (i.e. their knowledge of the importance of sleep health and the consequences of insufficient sleep) and sleep diary parameters using paired t-tests and Wilcoxon Signed Rank tests (for variables that remained skewed after attempting transformation to achieve a normal distribution). We conducted exploratory analyses to determine whether participating in the active intervention components was associated with changes in PROMIS scores, and correlated changes in sleep parameters that changed significantly with changes in PROMIS scores. We calculated Cohen’s d values for each significant analysis to determine the size of the effect. Due to expert consensus that adults should have more than 7 hours of sleep (7;8), and because individuals already obtaining a healthy amount of sleep would not be expected to increase their sleep at follow up, we also examined how participation in the program impacted the short sleepers (i.e., <7 hours of total sleep time at baseline).

Results

Feasibility

Participants were encouraged to participate in all parts of the study; however, some were skipped by some participants (the number of participants completing each section of the program is listed in Table 3). Eighty-eight (80%) of 110 attended the sleep health lecture. Ninety-eight of the 110 (89%) completed at least one active intervention component, and 77 (70%) participated in both active intervention components.

Table 3.

Sleep diary values and self-reported sleep questionnaires at pre- and post-lecture among participants who completed all intervention components.

| Variable | Mean Baseline (S.D.) |

Mean Post- Intervention (S.D.) |

Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test p- value or paired samples t-test‡ |

Cohen’s d effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep Knowledge (n=68) | ||||

| Sleep Beliefs Scalea | 13.06 (3.37) | 14.53 (3.00) | p<0.01 | 0.05 |

| SPAQ Importance of sleep by ageb |

1.22 (0.36) | 1.14 (0.33) | p=0.16 | |

| SPAQ Importance of sleep to healthb |

1.89 (0.77) | 1.81 (0.68) | p=0.40 | |

| SPAQ Sleep knowledgec | 2.25 (0.40) | 1.74 (0.46) | t=9.05, p<0.001 | 1.18 |

| Sleep Diary (n=77) | ||||

| In bed time | 12:07AM (1:06h) |

12:22AM (1:11h) |

p=0.01 | 0.22 |

| Lights out time | 12:53AM (1:09h) |

12:56AM (1:16h) |

t=−0.55, p=0.59 | |

| Sleep onset latency (mins) | 23.16 (19.82) | 14.96 (12.14) | p<0.0001 | 0.50 |

| Wake after sleep onset (mins) |

10.67 (11.53) | 9.62 (13.83) | p=0.13 | |

| Wake up time | 8:40AM (1:05h) |

8:37AM (1:01h) |

p=0.47 | |

| Out of bed time | 8:59AM (1:08h) | 8:44AM (1:05h) |

t=0.28, p=0.78 | |

| Time in bed (hrs) | 8:52h (1:02h) | 8:38h (1:04h) | t=2.35, p=0.02 | 0.23 |

| Total sleep time (hrs) | 7:12h (00:56h) | 7:17h (00:57h) |

t=−0.925, p=0.36 | |

| Sleep efficiency (%) | 92.34 (5.98) | 94.45 (5.40) | p<0.0001 | 0.37 |

| Texts received | 1.91 (2.04) | 0.96 (1.69) | p<0.0001 | 0.51 |

| Texts read | 1.05 (1.72) | 0.39 (1.17) | p<0.0001 | 0.45 |

| PROMIS Scalesd (n=62) | ||||

| Fatiguee | 56.24 (8.39) | 55.21 (10.00) | p=0.41 | |

| Sleep Disturbance | 54.44 (9.18) | 51.13 (9.12) | t=4.22, p<0.0001 | 0.36 |

| Sleep-Related Impairment | 59.98 (8.57) | 58.51 (10.13) | t=1.69, p=0.10 | |

| Anxiety | 58.75 (8.63) | 57.09 (8.43) | t=2.00, p=0.05 | |

| Depression | 55.35 (9.22) | 53.62 (8.92) | t=2.03, p=0.047 | 0.19 |

| Anger | 56.32 (9.77) | 54.46 (9.98) | t=1.73, p=0.09 | |

| Satisfaction in Discretionary Activitiese |

48.92 (7.04) | 50.18 (8.05) | p=0.35 | |

| Satisfaction in Social Roles |

47.20 (6.69) | 48.73 (8.16) | t=−1.74,p=0.09 | |

| Emotional Support | 52.03 (8.32) | 53.05 (8.60) | p=0.34 | |

| Social Isolation | 49.73 (9.36) | 47.43 (10.59) | t=2.35, p=0.02 | 0.23 |

n=62 lecture only; arange=0–20, higher scores indicate more accurate beliefs;

range=1–4, lower scores indicate greater importance;

range=1–5, lower scores indicate greater knowledge;

range=1–100, higher scores indicate greater level of that scale;

n=62;

p-value listed alone indicates that it is associated with Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test

Comparison of Lecture Attenders and Non-Attenders

A total of 117 eligible participants provided online consent for the study; seven did not participate further, 110 completed some aspect of the study, and 88 attended the sleep lecture. Because participants who attended the lecture may represent a biased sample, we conducted analyses comparing those who did (n=88) and did not (n=22) attend on demographic characteristics, sleep knowledge and patterns, and functional outcomes. The groups differed significantly on GPA, QPA, and SPAQ rating of the importance of sleep to each age group (see Table S1). Participants attending the lecture reported significantly higher GPA and QPA scores than those who did not attend the lecture. Those who attended the lecture had significantly lower scores on the SPAQ subscale, indicating they believed sleep was more important to each age group than those who did not attend.

Change from Pre- to Post-Intervention among Intervention Completers

The following analyses reflect changes among participants who completed the active intervention components.

Sleep knowledge. Participants who completed the SBS at baseline and post-lecture (n=62) demonstrated a significant increase in correct beliefs about sleep (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test p=0.001; see Table 3). We re-ran our analyses after include only those scoring below the median baseline score (n=31). These participants also showed a significant improvement from pre- to post-intervention (change of 2.48 points, p=0.001).Those who completed the SPAQ at baseline and post-lecture (n=68) demonstrated significantly more accurate sleep-related beliefs at post-lecture as compared to baseline (t=9.05, p<0.001; Table 3). Scores on the other SPAQ subscales did not change significantly.

Sleep diary parameters. Significant changes were seen among several sleep diary parameters post-lecture as compared to baseline (n=77; see Table 3), including delayed bed time (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test p<0.001), reduced time to fall asleep (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test p<0.001), reduced time in bed (t=2.35, p=0.021), and increased sleep efficiency (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test p<0.001). Additionally, the number of incoming text messages received and read after lights out significantly decreased from baseline to post-lecture, with received messages decreasing by an average of 0.95 messages (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test p<0.001), and read messages decreasing by an average of 0.65 messages (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test p<0.001; see Table 3). Effect sizes for these significant changes are shown in Table 3. We re-ran our analyses utilizing only the 5 weekdays from the sleep diary. When testing for changes in sleep diary parameters from pre- to post-intervention among those who completed all intervention components, we replicated our original findings of significant changes in bed time, time to fall asleep, time in bed, and sleep efficiency. We also found that wake time after sleep onset also significantly changed (all p<0.05).

Among the 27 short sleepers (< 7 hours at baseline) who completed both active intervention components, total sleep time increased by an average of 30.2 minutes (t=−2.98, p=0.01; Cohen’s d=0.60) and time to fall asleep decreased by 10.5 minutes on average (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test p=0.01; Cohen’s d=0.47) post-intervention. Sleep efficiency increased by an average of 3% (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test p=0.01; Cohen’s d=0.39), the average number of text messages received decreased significantly (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test p=0.01; Cohen’s d=0.35; decrease of 0.85 messages received) and the number of text messages read decreased significantly (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test p=0.04; Cohen’s d=0.30; decrease of 0.65 messages read). We re-ran our analyses in participants who slept < 7 hours when including only the 5 weekdays from the sleep diary (now n=37), which replicated our findings of significant changes in total sleep time, time to fall asleep, and sleep efficiency (all p<0.05). Additionally, we found that wake time after sleep onset also significantly reduced (p<0.05).

Because greater lifestyle regularity is associated with fewer sleep problems (51), examining day-to-day variability in sleep diary parameters may provide another index of sleep health. Wilcoxon signed rank tests showed that the day-to-day variability (standard deviation) was significantly reduced (all p<0.001) from baseline to post-lecture for sleep onset latency (20.85 to 11.35 minutes; Cohen’s d=0.46), sleep efficiency (7.56% to 4.77%; Cohen’s d=0.43), texts received (2.19 to 1.30 texts; Cohen’s d=0.51), and texts read (1.47 to 0.59 texts; Cohen’s d=0.57).

Psychosocial functioning. Among the intervention completers who also completed the PROMIS measures at both baseline and post-lecture (n=62), participants reported significant improvements in sleep disturbance (t=4.22, p<0.0001), depression (t=2.03, p=0.047), and social isolation (t=2.35, p=0.02; see Table 3 for effect sizes). Sleep disturbance scores demonstrated the greatest improvement of 3.25 points on average, roughly one-third of one standard deviation on this scale. Scores on the anxiety scale improved by 1.66 points (t=2.00, p=0.05), falling just below conventional levels of statistical significance.

We correlated pre-post measures of sleep variables that showed significant improvement from pre- to post-intervention with all psychosocial functioning scales to determine whether significant changes in sleep were associated with changes in psychosocial functioning. We found that a decrease in sleep onset latency (r=0.29, p=0.02) and a decrease in time in bed (r=0.34, p=0.01) were associated with a decrease in social isolation. We also found that improved sleep efficiency was associated with an increase in emotional support (r=0.33, p=0.01) and a decrease in social isolation (r=−0.26, p=0.04).

Participant Satisfaction

Participants were highly satisfied with the program. Program evaluation and sleep health lecture ratings (see Table 2) ranged from 3.07–4.33 (out of a maximum of 5), with 10 of the 15 items rated at 4.0 or higher. These scores indicate relatively high level of program acceptability in this college population.

Discussion

We found that it is feasible and acceptable to implement this sleep health promotion program, which consisted of disseminating the latest research on sleep health to college students via an in-person lecture and personalized feedback on participants’ sleep diary data; a total of 80% of enrolled participants attended the in-person lecture and 70% completed all active intervention components. In this open-label trial, we also found improvements in both knowledge about sleep as well as sleep diary parameters including sleep efficiency, and in the shortest sleepers, total sleep time. Specifically, among participants who completed all active intervention components, we observed significantly improved sleep knowledge as well as delayed time getting into bed, reduced time it takes to fall asleep, reduced time in bed, and increased sleep efficiency at the conclusion of the study. While the intervention did not focus on sleep restriction as an intervention, it did emphasize limiting ‘sleep stealers’ in the bed (similar to stimulus control (52)). Thus, the reduced time in bed may have been the result of reducing time in bed doing activities like reading and watching TV, although this was not specifically assessed. Similarly, the fact that participants delayed their time of getting into bed by 15 minutes may be related to our instructions to engage in fewer sleep-incompatible behaviors in bed. Variability in sleep onset latency and sleep efficiency also decreased, suggesting increased day-to-day regularity in some aspects of sleep. While we did not observe increases in sleep duration among the entire sample, we saw sleep duration improvements in the short sleepers, the portion of the sample most in need of additional sleep. Finally, we also observed improvements in the PROMIS measures of depression and social isolation. Short sleep duration and sleep disturbances have been repeatedly shown to heighten risk for depression, and sleep complaints are nearly universal in individuals with mood disorders (53–55). Thus, improving sleep in college students may also have a positive influence on depression symptoms and other psychosocial outcomes. Overall, the changes in knowledge and behaviors related to sleep suggest that this tailored approach for conveying the relevance of sleep-health to college students is promising. While the sizes of most of these effects were small to medium, we observed large effects for improvement in SPAQ sleep knowledge among the entire sample (Cohen’s d=1.18) and improvement in sleep duration among the shortest sleepers (Cohen’s d=0.60), suggesting that our intervention had large impacts on these particular areas. Moreover, we found preliminary evidence that significant changes in sleep are associated with subsequent changes in perceived emotional support and social isolation.

Knowledge-based interventions have the advantage of being scalable, accessible, and cost-effective, which is particularly well-suited for college students (19). In addition to providing psychoeducation pertaining to sleep, to our knowledge, our program is the first sleep health program for college students to provide tailored feedback to each individual. Because the combination of factors that influence sleep practices is unique to each individual, tailored health promotion programs are advantageous because they pay attention to inter-individual differences, as well as differences in desired sleep outcomes (35). Our feedback was relatively simple, but could be further tailored by making more specific recommendations based on an individual’s data. Personalized feedback interventions (PFIs) have been shown to be effective for improving other health behaviors among college samples, such as alcohol use. One recent review (56) found that PFIs are effective at reducing short-term alcohol consumption and that incorporating personally-relevant information about the consequences of drinking may be one way to enhance short-term effectiveness. Our efforts to tailor feedback to each participant are consistent with this strategy.

Results from this study are also consistent with previous findings on sleep among college students. At baseline, average sleep duration in our sample was 7:08 hours of sleep across the week, similar to a recent report of 7:01 hours of sleep across the week (6), and similar to the 7:10 hours reported in a sample of young adults from the United States.(57) In our sample, 21.4% reported less than 6.5 hours of sleep on average, similar to the 25% of another college sample who reported less than 6.5 hours of sleep per night (6), and the 21% of a young adult sample from 24 countries who slept less than 7 hours (6% at <6 hours, 15% 6–7 hours) (57). Our findings are also consistent with those of previous sleep education program trials among college students, which showed improvements in sleep knowledge and aspects of sleep habits (20;21). Those studies specifically demonstrated improvements in sleep knowledge, sleep quality, depressive symptoms, and wake time. However, to our knowledge, ours is the first to show reduced sleep onset latency and total time spent in bed, and to demonstrate correlations among changes in sleep parameters and changes in psychosocial outcomes of interest. Sleep efficiency was also found to increase, though this is not surprising given that sleep efficiency is determined by some of the sleep variables that showed improvement.

As an exploratory, open trial, we primarily aimed to assess the feasibility of implementing and evaluating a tailored sleep health promotion program to college students. We met our completion goal of 80% of participants completing at least one intervention component. However, as an exploratory, open trial, our findings are limited due to lack of a control group. We therefore cannot say that improvements in any of our outcomes were due to our program, as opposed to a re-testing or expectation effect. It will be particularly important for future work to include a control group since the control groups of some previous randomized controlled trials of sleep education programs have demonstrated improvements in sleep knowledge and quality (20;21;28). Also, tracking sleep with a sleep diary may itself constitute an intervention on its own, perhaps because monitoring leads to changes in the perception of a sleep complaint(58), or because patients obtain insight by linking sleep habits with sleep quality and quantity, particularly among individuals with insomnia (59). Additionally, it is possible that the changes in sleep patterns, particularly among the shortest sleepers, may be explained by a ‘regression to the mean’ effect. In this case, short sleepers may have been sleeping less than usual before the intervention, and the improvement in their sleep may be due to ‘catching up’ on sleep. However, our findings do provide promising preliminary evidence that promoting sleep health in college students is possible, and may be associated with improvements in sleep and other aspects of functioning. Subsequent evaluation including a control group is needed to test this approach.

Limitations

We were unable to follow participants longitudinally to determine whether any changes in sleep were stable or changed over time (e.g., 3 or 6 months later). Future work should include a follow-up assessment to determine the longer-term impact of our program. Additionally, the specific timing of our intervention in relation to the students’ semester schedule may constitute a limitation. The active parts of the program occurred prior to a brief school holiday, while the post-intervention sleep diary assessment began after this break and the other questionnaires completed one week later, which was the penultimate week before end-of-the-semester finals. On the one hand, individuals may have returned rested (or not) from the break, and were also heading into the end of the semester. It’s plausible that both of these environmental factors could have impacted student’s sleep. Actigraphy, a measure of rest-activity rhythms that is used as a proxy for sleep, could provide objective data on sleep parameters, although the expense and data cleaning procedures involved may limit the feasibility of using actigraphy in sleep-health dissemination programs in larger samples. Several recent studies, however, have demonstrated that it is possible to utilize this type of equipment to collect data in large samples (60;61). Nevertheless, strategies using personal consumer electronics, such as online sleep coaches, fitness trackers, and/or web-based lectures, may further increase feasibility in collecting data and providing tailored feedback to participants.

It is possible that our emphasis on increasing motivation to change behavior by enhancing program relevance, providing tailored feedback, and enabling comparison to other similar individuals contributed to the changes in sleep as a result of improvements in sleep knowledge. However, we were not able to determine which component(s) of our program may have contributed to improvements in sleep-related knowledge and sleep diary parameters; doing so could lead to a simpler, more efficient intervention. Participants were reimbursed up to $50 for their participation, which may have had an effect on their motivation to complete the study program. Thus, while participants generally appeared to be satisfied with the program, we do not know to what extent participant study reimbursements contributed to interest and participation rates. Last, our study included primarily females as this reflected the gender composition of the University from which participants were recruited. Because college-aged women tend to have poorer sleep continuity, poorer sleep quality, and decreased total sleep time than men (62;63), we do not know how these findings would generalize to men. Replicating these findings with a control group, and also with a more balanced group of males and female college students are important next steps.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that it is feasible and acceptable to disseminate information on sleep health to college students via individually tailored reports of sleep diary data and attending an in-person, hour-long presentation on sleep health. Our program was associated with significant changes in sleep-related knowledge and several diary-based sleep outcomes. Students most in need of improvements in their sleep health in terms of obtaining sufficient sleep reported longer sleep durations after participating in the program, suggesting that such a program can be targeted to those individuals in greatest need for this information. Future work should aim to test the efficacy of this program in a fully-powered randomized clinical trial, and to determine the most effective, scalable approach to disseminating relevant sleep health information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part from the University of Pittsburgh Clinical Translational Science Institute UL1 RR024153 and UL1TR000005 and by NIH grant T32 HL082610 (Program Director: Buysse).

Appendix A

Selected items of the Sleep Practices and Attitudes Questionnaire(41) with associated domains.

Importance of Sleep by Age

How important is getting healthy sleep for… (Rated from 1, Very Important to 4, Not Important) Children growing up?

Adults?

Older adults/seniors?

Importance of Sleep to Overall Health

How much do you agree/disagree with the following statements? (Rated from 1, Strongly Agree to 5, Strongly Disagree)

I care about making sure that I have enough time to sleep

Getting enough sleep is important for me to be able to enjoy the day

My sleep is important to my health

Sleep-Related Knowledge

How much do you agree/disagree with the following statements? (Rated from 1, Strongly Agree to 5, Strongly Disagree)

Not enough sleep can lead to serious consequences

Dozing while driving a vehicle is serious

Lying in bed with your eyes shut is as good as sleeping

Opening the car window is a good way to wake me up if I am drowsy while driving

Turning up the volume of the radio or music is a good way to wake me up if I am drowsy while driving

If I don’t get enough sleep, it can cause me to: (Rated from 1, Strongly Agree to 5, Strongly Disagree)

Feel sleepy during the day

Fall asleep while driving

Gain weight

Develop heart disease

Raise cholesterol

Develop hypertension (high blood pressure)

Be more moody

Have less energy

Have a lower sex drive

Miss more days of work or school

Perform worse at work or school

Have problems remembering things or concentrating

Develop diabetes

Feel tired

Reference List

- 1.Buysse DJ. Sleep health: Can we define it? Does it matter? Sleep. 2014;37(1):9–17. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore M, Meltzer LJ. The sleepy adolescent: causes and consequences of sleepiness in teens. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2008 Jun;9(2):114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carskadon MA, Acebo C, Jenni OG. Regulation of adolescent sleep: implications for behavior. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004 Jun;1021:276–291. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Millman RP. Excessive sleepiness in adolescents and young adults: causes, consequences, and treatment strategies. Pediatrics. 2005 Jun;115(6):1774–1786. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hershner SD, Chervin RD. Causes and consequences of sleepiness among college students. Nat Sci Sleep. 2014;6:73–84. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S62907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lund HG, Reider BD, Whiting AB, Prichard JR. Sleep patterns and predictors of disturbed sleep in a large population of college students. J Adolesc Health. 2010 Feb;46(2):124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, Alessi C, Bruni O, DonCarlos L, et al. National Sleep Foundations' sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health. 2015;1(1):40–43. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G, Bliwise DL, Buxton OM, Buysse D, et al. Recommended Amount of Sleep for a Healthy Adult: A Joint Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Sleep. 2015;38(6):843–844. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petrov ME, Lichstein KL, Baldwin CM. Prevalence of sleep disorders by sex and ethnicity among older adolescents and emerging adults: relations to daytime functioning, working memory and mental health. J Adolesc. 2014 Jul;37(5):587–597. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trockel MT, Barnes MD, Egget DL. Health-related variables and academic performance among first-year college students: implications for sleep and other behaviors. J Am Coll Health. 2000 Nov;49(3):125–131. doi: 10.1080/07448480009596294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly WE, Kelly KE, Clanton RC. The relationship between sleep length and grade-point average among college students. College Student Journal. 2001;35(1):84–86. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eliasson AH, Lettieri CJ, Eliasson AH. Early to bed, early to rise! Sleep habits and academic performance in college students. Sleep Breath. 2010 Feb;14(1):71–75. doi: 10.1007/s11325-009-0282-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor DJ, Bramoweth AD. Patterns and consequences of inadequate sleep in college students: substance use and motor vehicle accidents. J Adolesc Health. 2010 Jun;46(6):610–612. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Regestein Q, Natarajan V, Pavlova M, Kawasaki S, Gleason R, Koff E. Sleep debt and depression in female college students. Psychiatry Res. 2010 Mar 30;176(1):34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brooks PR, Giigenti AA, Milles MJ. Sleep patterns and symptoms of depression in college students. College Student Journal. 2009;43(2):464–472. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamdar BB, Kaplan KA, Kezirian EJ, Dement WC. The impact of extended sleep on daytime alertness, vigilance, and mood. Sleep Med. 2004 Sep;5(5):441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mah CD, Mah KE, Kezirian EJ, Dement WC. The effects of sleep extension on the athletic performance of collegiate basketball players. Sleep. 2011 Jul;34(7):943–950. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kloss JD, Nash CO, Horsey SE, Taylor DJ. The delivery of behavioral sleep medicine to college students. J Adolesc Health. 2011 Jun;48(6):553–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quan SF, Anderson JL, Hodge GK. Use of a supplementary internet based education program improves sleep literacy in college psychology students. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013 Feb 1;9(2):155–160. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trockel M, Manber R, Chang V, Thurston A, Taylor CB. An e-mail delivered CBT for sleep-health program for college students: effects on sleep quality and depression symptoms. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011 Jun 15;7(3):276–281. doi: 10.5664/JCSM.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown FC, Buboltz WC, Jr, Soper B. Development and evaluation of the Sleep Treatment and Education Program for Students (STEPS) J Am Coll Health. 2006 Jan;54(4):231–237. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.4.231-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ye L, Smith A. Developing and Testing a Sleep Education Program for College Nursing Students. J Nurs Educ. 2015 Sep 1;54(9):532–535. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20150814-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cortesi F, Giannotti F, Sebastiani T, Bruni O, Ottaviano S. Knowledge of sleep in Italian high school students: pilot-test of a school-based sleep educational program. J Adolesc Health. 2004 Apr;34(4):344–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moseley L, Gradisar M. Evaluation of a school-based intervention for adolescent sleep problems. Sleep. 2009 Mar;32(3):334–341. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.3.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kira G, Maddison R, Hull M, Blunden S, Olds T. Sleep education improves the sleep duration of adolescents: a randomized controlled pilot study. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2014;10(7):787–792. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cain N, Gradisar M, Moseley L. A motivational school-based intervention for adolescent sleep problems. Sleep Med. 2011 Mar;12(3):246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wing YK, Chan NY, Man Yu MW, Lam SP, Zhang J, Li SX, et al. A school-based sleep education program for adolescents: a cluster randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015 Mar;135(3):e635–e643. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan E, Healey D, Gray AR, Galland BC. Sleep hygiene intervention for youth aged 10 to 18 years with problematic sleep: a before-after pilot study. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:189. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Sousa IC, Araujo JF, De Azevedo CVM. The effect of a sleep hygiene education program on the sleep–wake cycle of Brazilian adolescent students. Sleep and Biological Rhythms. 2007;5(4):251–258. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spivak K, Sanchez-Craig M, Davila R. Assisting problem drinkers to change on their own: effect of specific and non-specific advice. Addiction. 1994 Sep;89(9):1135–1142. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb02790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanchez-Craig M, Davila R, Cooper G. A self-help approach for high-risk drinking: effect of an initial assessment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996 Aug;64(4):694–700. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.4.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agostinelli G, Miller WR. Drinking and thinking: how does personal drinking affect judgments of prevalence and risk? J Stud Alcohol. 1994 May;55(3):327–337. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol Bull. 2007 Jul;133(4):673–693. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cassoff J, Knauper B, Michaelsen S, Gruber R. School-based sleep promotion programs: effectiveness, feasibility and insights for future research. Sleep Med Rev. 2013 Jun;17(3):207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ajzen I, Madden TJ. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1986;22:453–474. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Cancer Institute. Theory at a glance: A guide for health promotion practice. Bethesda, MD: Naitonal Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gershon RC, Rothrock N, Hanrahan R, Bass M, Cella D. The use of PROMIS and assessment center to deliver patient-reported outcome measures in clinical research. J Appl Meas. 2010;11(3):304–314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adan A, Fabbri M, Natale V, Prat G. Sleep Beliefs Scale (SBS) and circadian typology. J Sleep Res. 2006 Jun;15(2):125–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2006.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grandner MA, Jackson N, Gooneratne NS, Patel NP. The development of a questionnaire to assess sleep-related practices, beliefs, and attitudes. Behav Sleep Med. 2014 Mar 4;12(2):123–142. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2013.764530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Monk TH, Reynolds CF, Kupfer DJ, Buysse DJ, Coble PA, Hayes AJ, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Diary. J Sleep Res. 1994;3(2):111–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Cook KF, Crane PK, Teresi JA, et al. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Med Care. 2007 May;45(5 Suppl 1):S22–S31. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250483.85507.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fries JF, Bruce B, Cella D. The promise of PROMIS: using item response theory to improve assessment of patient-reported outcomes. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005 Sep;23(5 Suppl 39):S53–S57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buysse DJ, Yu L, Moul DE, Germain A, Stover A, Dodds NE, et al. Development and validation of patient-reported outcome measures for sleep disturbance and sleep-related impairments. Sleep. 2010 Jun 1;33(6):781–792. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.6.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu L, Buysse DJ, Germain A, Moul DE, Stover A, Dodds NE, et al. Development of short forms from the PROMIS Sleep Disturbance and Sleep-Related Impairment item banks. Behav Sleep Med. 2012;10(1):6–24. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2012.636266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hahn EA, Devellis RF, Bode RK, Garcia SF, Castel LD, Eisen SV, et al. Measuring social health in the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS): item bank development and testing. Qual Life Res. 2010 Sep;19(7):1035–1044. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9654-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hahn EA, DeWalt DA, Bode RK, Garcia SF, Devellis RF, Correia H, et al. New English and Spanish social health measures will facilitate evaluating health determinants. Health Psychol. 2014 May;33(5):490–499. doi: 10.1037/hea0000055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lai JS, Cella D, Choi S, Junghaenel DU, Christodoulou C, Gershon R, et al. How item banks and their application can influence measurement practice in rehabilitation medicine: a PROMIS fatigue item bank example. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011 Oct;92(10 Suppl):S20–S27. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, Stover AM, Riley WT, Cella D. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS(R)): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment. 2011 Sep;18(3):263–283. doi: 10.1177/1073191111411667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Monk TH, Reynolds CF, Buysse DJ, DeGrazia JM, Kupfer DJ. The relationship between lifestyle regularity and subjective sleep quality. Chronobiol Int. 2003;20(1):97–107. doi: 10.1081/cbi-120017812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bootzin RR, Smith LJ, Franzen PL, Shapiro SL. Stimulus control therapy. In: Sateia MJ, Buysse DJ, editors. Insomnia: Diagnosis and Treatment. London: Informa Healthcare; 2010. pp. 268–276. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Franzen PL, Buysse DJ. Sleep disturbances and depression: risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2008;10(4):473–481. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.4/plfranzen. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, Spiegelhalder K, Nissen C, Voderholzer U, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2011 Dec;135(1–3):10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhai L, Zhang H, Zhang D. SLEEP DURATION AND DEPRESSION AMONG ADULTS: A META-ANALYSIS OF PROSPECTIVE STUDIES. Depress Anxiety. 2015 Jun 5; doi: 10.1002/da.22386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miller MB, Leffingwell T, Claborn K, Meier E, Walters S, Neighbors C. Personalized feedback interventions for college alcohol misuse: an update of Walters & Neighbors (2005) Psychol Addict Behav. 2013 Dec;27(4):909–920. doi: 10.1037/a0031174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Steptoe A, Peacey V, Wardle J. Sleep duration and health in young adults. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Sep 18;166(16):1689–1692. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.16.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Perlis ML, McCall WV, Jungquist CR, Pigeon WR, Matteson SE. Placebo effects in primary insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2005 Oct;9(5):381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Currie SR. Sleep Disorders. In: Hunsley J, Mash EJ, editors. A Guide to Assessments That Work. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 535–551. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bonnar D, Gradisar M, Moseley L, Coughlin AM, Cain N, Short MA. Evaluation of novel school-based interventions for adolescent sleep problems: does parental involvement and bright light improve outcomes? Sleep Health. 2015;1:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rigney G, Blunden S, Maher C, Dollman J, Parvazian S, Matricciani L, et al. Can a school-based sleep education programme improve sleep knowledge, hygiene and behaviours using a randomised controlled trial. Sleep Med. 2015 Jun;16(6):736–745. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.02.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Buboltz WC, Jr, Brown F, Soper B. Sleep habits and patterns of college students: a preliminary study. J Am Coll Health. 2001 Nov;50(3):131–135. doi: 10.1080/07448480109596017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tsai LL, Li SP. Sleep patterns in college students: gender and grade differences. J Psychosom Res. 2004 Feb;56(2):231–237. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00507-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.