INTRODUCTION

Like most organ systems throughout the body, the brain requires insulin and insulinlike growth factors (IGFs) to maintain energy metabolism, cell survival, and homeostasis. In addition, insulin and IGFs support neuronal plasticity and cholinergic functions, which are needed for learning, memory, and myelin maintenance. Impairments in insulin and IGF signaling, caused by receptor resistance or ligand deficiency, disrupt energy balance and disable networks that support a broad range of brain functions. Over the past several years, evidence that impairment in brain insulin and IGF signaling mediates cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration has grown, particularly in relation to mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease (AD). Although amyloid deposits and phospho-tau–associated neuronal cytoskeletal lesions account for some AD-associated brain abnormalities, they do not explain the prominent and well-documented deficits in brain metabolism that begin very early in the course of the disease. Metabolic derangements in AD are similar to those in both type 1 type and 2 diabetes mellitus. However, the consequences of insulin/IGF receptor resistance and ligand deficiency include cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration caused by deficits in signaling through progrowth, proplasticity, and prosurvival pathways.

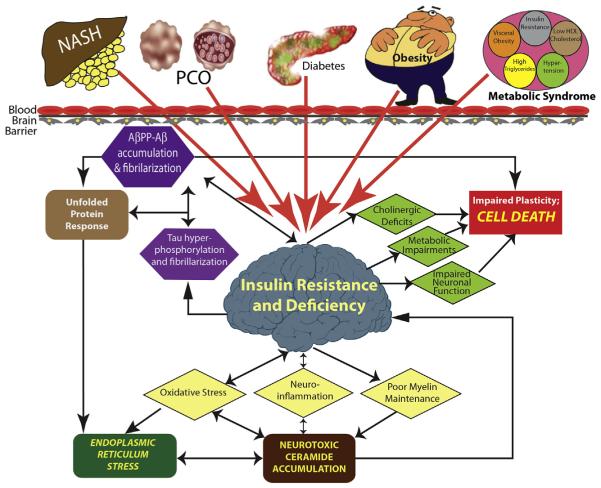

How brain insulin/IGF resistance and deficiency develop is not completely understood. Although a considerable number of studies have linked the recently increased rates of AD to other insulin resistance states, including obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and metabolic syndrome, it is important to realize that most cases of sporadic (nonfamilial) AD arise with no evidence of peripheral insulin-resistance disease. This review focuses on how peripheral insulin-resistance diseases, including diabetes mellitus, contribute to cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration. The working hypothesis is that peripheral insulin resistance promotes or exacerbates cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration by causing brain insulin resistance. Mechanistically, insulin resistance with dysregulated lipid metabolism leads to increased inflammation, cytotoxic lipid production, oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and worsening of insulin resistance. Some investigators are researching the role of cytotoxic ceramides that can promote inflammation, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance. Ceramides generated in liver or visceral fat can leak into peripheral blood because of local cellular injury or death, cross the blood-brain barrier, and initiate or propagate a cascade of neurodegeneration mediated by brain insulin resistance, inflammation, stress, and cell death (Fig. 1). These concepts help delineate the strategies needed to detect, monitor, treat, and prevent AD as well as other major insulin-resistance diseases.

Fig. 1.

Concept: Systemic insulin-resistance diseases mediate brain insulin/IGF resistance and neurodegeneration. In T2DM, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), visceral obesity, and metabolic syndrome, dysregulated lipid metabolism causes oxidative stress and increased levels of toxic lipids, such as ceramides, which can cross the blood-brain barrier to promote brain insulin resistance. The molecular and biochemical consequences of brain insulin resistance are nearly identical to those in non–central nervous system organs and tissues (ie, oxidative stress, inflammation, ER stress, metabolic impairments, and local accumulations of neurotoxic lipids, [eg, ceramides]). However, the structural consequences are that the brain undergoes atrophy with progressive cell loss, white matter fiber and myelin degeneration, and synaptic disconnection, leading to impairments in learning and memory. Ultimately, a self-reinforcing cycle of neurodegeneration gets established, making it impossible to halt neurodegeneration by one mechanism. Instead, multipronged efforts must be used, including treatment of systemic insulin-resistance diseases. AβPP, amyloid-beta precursor protein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; PCO, polycystic ovarian syndrome.

INSULIN SIGNALING

The Master Hormone

Insulin is a 5800 Da, 51 amino acid polypeptide, composed of A (21 residues) and B (30 residues) chains linked by disulfide bonds. Banting, Best and others are credited for discovering insulin in pancreatic secretions,1,2 and later it was shown that it reversed hyperglycemia.3 Nearly 30 years later, methods to stabilize insulin, prolong its actions, and delay its absorption emerged; 50 years after its discovery, 99% pure insulin, free of proinsulin and other islet polypeptides, was produced.4 Genetic engineering and yeast fermentation technology have enabled human insulin to be efficiently produced on a large scale.5 The field continues to evolve, with some of the latest advances directed toward replacing injectable insulin with an oral form6 and optimizing approaches for intranasal delivery of insulin to treat diabetes or cognitive impairment (see later discussion).7–9

Insulin-Stimulated Effects

The main targets of insulin stimulation include skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, and liver, although virtually all organs, tissues, and cell types are responsive to insulin. Insulin regulates glucose uptake and utilization by cells and free fatty acid levels in peripheral blood. Free fatty acids are substrates for generating complex lipids. In skeletal muscle, insulin stimulates glucose uptake by inducing translocation of the glucose transporter protein, GLUT4, from the Golgi to the plasma membrane.10 In liver, insulin stimulates lipogenesis and triglyceride storage and inhibits gluconeogenesis. In adipose tissue, insulin decreases lipolysis and fatty acid efflux.11 These prometabolic effects of insulin on glucose and free fatty acid disposal help to maintain energy balance.

IGFs

Insulin is closely related to IGF-1, which is also referred to as somatomedin C or mechano growth factor.12,13 IGF-1 regulates growth during development and exerts anabolic effects on mature organs and tissues. IGF-1 contains 70 amino acids (7649 Da) in a single chain with 3 intramolecular disulfide bridges.12,13 IGF-1 and IGF-2 are abundantly produced in liver and regulated by IGF-binding proteins.14

Insulin and IGF Signaling in the Brain

Within the last 15 to 20 years, information has steadily emerged about the expression and function of insulin and IGF polypeptides and receptors in the brain. It is now known that insulin and IGF signal to regulate a broad array of neuronal and glial activities, including growth, survival, metabolism, gene expression, protein synthesis, cytoskeletal assembly, synapse formation, neurotransmitter function, and plasticity,15,16 which are needed to support cognitive function. Insulin, IGF-1, and IGF-2 polypeptide and receptor genes are expressed in neurons15 and glial cells17,18 throughout the brain; but their highest levels are within structures targeted by neurodegeneration.15,19,20 Since genes that encode insulin, IGFs, and insulin-like peptides and their receptors have been identified in human, rodent, and drosophila brains,21 related signaling networks allow for local control of diverse functions, including energy metabolism.

Insulin and IGF Signal Transduction

Brain insulin/IGF signaling mechanisms are virtually the same as in other organs. The networks are activated by ligand binding to specific receptors and subsequent activation of receptor tyrosine kinases and downstream signaling through insulin receptor substrate (IRS) proteins. The attendant activation of phosphoinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt and extracellular mitogen-activated protein kinase and the inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3b (GSK-3β) promote growth, survival, metabolism, and plasticity and inhibit apoptosis.20

INSULIN RESISTANCE AND NEURODEGENERATION

Insulin Resistance and its Consequences

Insulin resistance is classically defined as the state in which high levels of circulating insulin (hyperinsulinemia) are associated with hyperglycemia. The concept has broadened to include organand tissue-related impairments in insulin signaling associated with reduced activation of the pathways. As a result, progressively higher levels of ligand are needed to achieve normal insulin actions.10 However, sustained high levels of insulin can cause insulin resistance,22 thereby worsening and possibly broadening tissue involvement. Furthermore, hyperinsulinemia impairs insulin secretion from β cells in pancreatic islets, yielding hybrid states of both insulin resistance and insulin deficiency.22

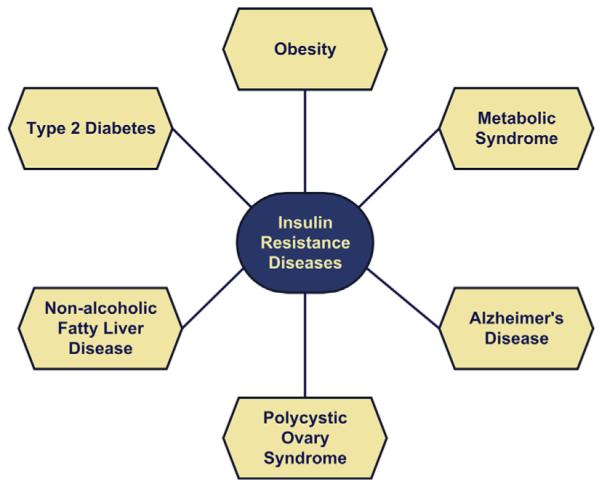

Long-term consequences of insulin resistance include cellular energy failure (lack of fuel), elevated plasma lipids, and hypertension. In addition, chronic hyperinsulinemia vis-á-vis normoglycemia predicts future development of diabetes mellitus.23 Insulin resistance is an independent predictor of serious diseases, including cerebrovascular and cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and malignancy.24–28 Insulin resistance is now front and center stage because of its link to obesity, T2DM, NAFLD, metabolic syndrome, polycystic ovarian disease, age-related macular degeneration, and AD epidemics (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Spectrum of insulin-resistance diseases affecting different primary target organs. Overlap among these diseases occurs frequently, and rates have increased with the obesity epidemic.

AD Occurrence and Clinical Diagnosis

AD is the most common cause of dementia in North America. Sporadic AD has no clear genetic transmission and accounts for more than 90% of the cases. In contrast, familial (heritable) AD accounts for 5% to 10% of all cases. Over the past few decades, sporadic AD has become epidemic, raising questions about environmental and lifestyle mediators of cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration.29 Although the clinical diagnosis of AD is based on criteria set by the National Institute of Neurologic and Communicative Disorders and Stroke, the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association, and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition),30 neuroimaging and a few biomarker panels have facilitated the detection of early brain metabolic derangements in AD.31

AD Neuropathology

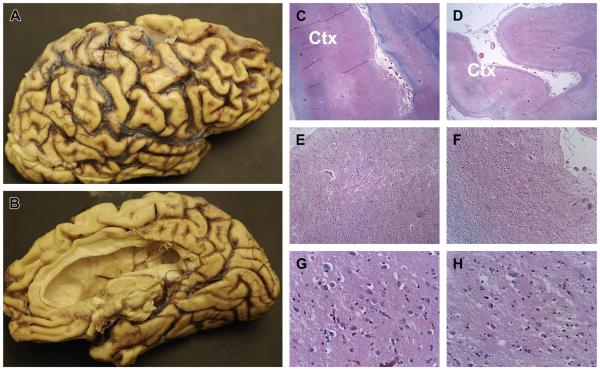

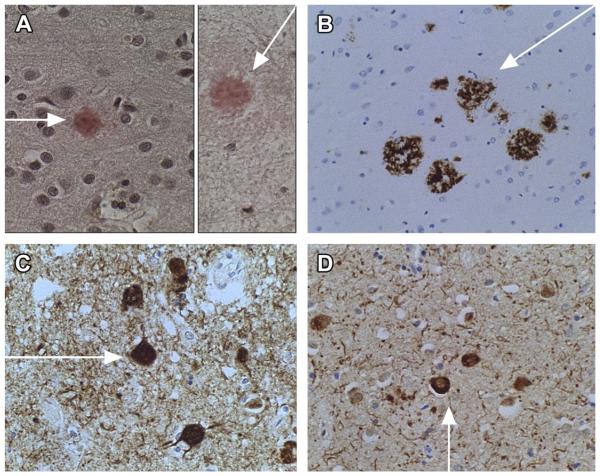

Neuropathologic hallmarks of AD include neuronal loss, abundant accumulations of abnormal, hyperphosphorylated cytoskeletal proteins in neuronal perikarya and dystrophic fibers, and increased expression and abnormal processing of amyloid-beta precursor protein (AβPP), leading to AβPP-Aβ peptide deposition in neurons, plaques, and vessels. A definitive diagnosis of AD requires more-than-normal aging densities of neurofibrillary tangles, neuritic plaques, and AβPP-Aβ deposits in the brain but particularly in corticolimbic structures (Figs. 3–5). The pathognomonic molecular abnormalities that correspond with these dementia-associated structural lesions include accumulations of insoluble aggregates of abnormally phosphorylated and ubiquitinated tau, and neurotoxic AβPP-Aβ as oligomers, fibrillar aggregates, or plaques. Secreted neurotoxic AβPP-Aβ oligomers inhibit synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory via impairments in hippocampal long-term potentiation.32

Fig. 3.

Human brain with severe AD showing extreme atrophy of the cortex with thinning of gyri (tan curvy hill-like structures) and widening of sulci (grooves between gyri). (A) Lateral surface of right hemisphere-frontal lobe to right, parietal is toward the middle, occipital to left, and temporal at the base. (B) Same half-brain as in (A) showing medial surface with frontal pole to the left, occipital on the right. Frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes are markedly atrophic. (C, E, G) Represent histologic images of the left temporal lobe and (D, F, H) represent the right temporal lobe shown at low (C, D), medium (E, F) and high (G, H) magnifications to illustrate more severe atrophy of the cortex (Ctx) with extensive replacement of neurons in the right compared with left temporal lobe. Note absence (loss) of large neuronal cell bodies in (H) compared with (G). Both sides are severely damaged; but asymmetry is not uncommon, meaning that neurodegeneration does not arise in all brain regions or progress in both hemispheres at the same time ([C–H] Luxol fast blue, hematoxylin-eosin, original magnifications: C, D = ×20; E, F = ×100; G, H = ×400).

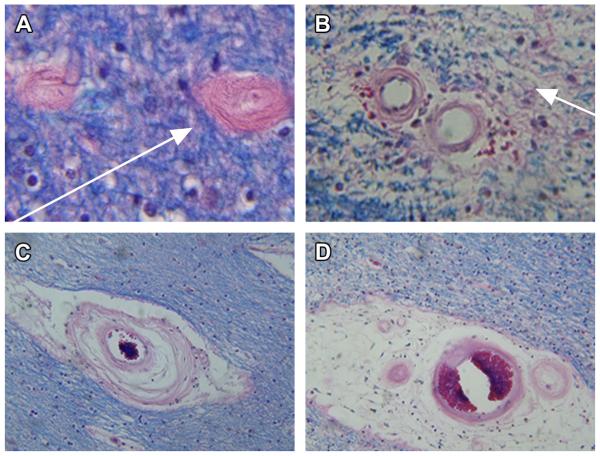

Fig. 5.

Typical histopathologic lesions in AD. Arrows point to the following: (A) dense core plaques in cerebral cortex (Congo red); (B) amyloid precursor protein-amyloid beta (AβPP-Aβ) immunoreactivity in cortical plaques; (C) phospho-tau immunoreactive neurofibrillary tangles accumulated in cortical neurons; and (D) ubiquitin immunostained neurofibrillary tangles in neurons. Fine dotlike and linear structures in the background neutrophil of (C, D) represent dystrophic neuritis. Immunoreactivity was detected with biotinylated secondary antibody, horseradish peroxidase conjugated streptavidin, and diaminobenzidine (brown precipitate). Background structures were stained with hematoxylin (original magnifications: A, C, D = ×200; B = ×100).

AD is a Metabolic Disease with Brain Insulin/IGF Resistance

For the better part of the last 3 decades, AD research was largely focused on the pathogenic roles of hyperphosphorylated tau and AβPP-Aβ, despite hints that insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction were important factors.33,34 With the wealth of data collected over the past 8 to10 years, it is fair to state that AD should be regarded as a metabolic disease that is mediated by brain insulin and IGF resistance.35,36 This concept is supported by the findings that AD shares many features in common with systemic insulin-resistance diseases. For example, reduced insulin-stimulated growth and survival signaling, increased oxidative stress, proinflammatory cytokine activation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and impaired energy metabolism all occur in peripheral insulin-resistance diseases as well as in AD (Table 1).20,37,38 In the early stages of disease, AD is marked by reductions in cerebral glucose utilization39–41; as AD progresses, brain metabolic derangements,42,43 including impairments in insulin signaling, insulin-responsive gene expression, glucose utilization, and energy production, and stress worsen.35,36,44

Table 1.

Mechanisms and consequences of cellular injury and degeneration in insulin-resistance diseases

| Mediator of Injury | Mechanisms and Consequences of Injury |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Inflammation | Activation of proinflammatory cytokines |

|

| |

| Stress | ER, oxidative, and nitrosative stress; DNA, RNA, protein damage and adduct formation |

|

| |

| Cell injury/death | Activation of proapoptosis pathways |

|

| |

| Metabolic deficiencies | Dysregulated lipid metabolism, lipid peroxidation |

|

| |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction | Reduced ATP production, increased reactive oxygen species |

|

| |

| Vascular | Stress and mechanical injuy, ischemic tissue damage, end-organ hypertensive injury with microhemorrhages and toxin exposure |

Brain Insulin and IGF Resistance and Deficiency in AD-Human Studies

Human postmortem studies have convincingly shown that brain insulin resistance with reduced activation of receptors and downstream neuronal survival and plasticity mechanisms are consistent and fundamental abnormalities in AD.35,36,44 Importantly, IGF-1 and IGF-2 networks were also found to be impaired,35,36 meaning that their crosstalk functions were also deficient. Deficits in brain insulin and IGF signaling worsen as AD progresses,35 along with declines in brain energy production, gene expression, and plasticity.33 One of the most important realizations from these studies was that nearly all of the critical features of AD, including the activation of the kinases responsible for aberrant phosphorylation of tau and formation of neurofibrillary tangles, dystrophic neuritic plaques and neutrophil threads, AβPP and accumulation and toxicity, oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cholinergic dyshomeostasis, can be explained by brain insulin/IGF resistance.

Does AD = Type 3 Diabetes?

Although the term type 3 diabetes is controversial, it serves to inform that the fundamental abnormalities in AD are quite similar to those present in type 1 and type 2 diabetes, except the primary target is the brain.35,36 Like type 1 diabetes (T1DM) in which insulin deficiency is the underlying problem, in AD, neuronal expression of insulin polypeptide gene and insulin levels in brain and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) are reduced.34–36 As in T2DM, which has insulin resistance at its core, early AD is marked by insulin resistance and desensitization of insulin receptors in the brain; as AD progresses, these deficits worsen. In essence, AD can be regarded as a brain form of diabetes that has elements of both insulin resistance (T2DM) and insulin deficiency (T1DM). Although T1DM and T2DM can be associated with cognitive impairment and drive the onset or worsen the clinical course of AD, it is important to know that AD often occurs in people who do not have diabetes mellitus (Table 2). The notion that AD is a diabetes-type metabolic disease that is mediated by brain insulin and IGF resistance is further supported by human and experimental studies showing neuroprotective effects of glucagonlike peptide-1,45 IGF-1,46 and caloric restriction47 with respect to brain aging and insulin resistance.

Table 2.

Comparison of T1DM, T2DM, and type 3 diabetes

| Target Effects | T1DM | T2DM | Type 3 Diabetes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Insulin ligand | Reduced | Increased | Reduced |

|

| |||

| Insulin receptor | Unaffected or increased | Reduced activation | Reduced activation and expression |

|

| |||

| Glucose utilization |

Decreased | Decreased | Decreased |

|

| |||

| Primary targets | Pancreas, (brain) | Skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, vessels |

Brain: neurons, white matter |

|

| |||

| Secondary targets |

Brain, retina, blood vessels, kidneys, skin, peripheral and autonomic nerves |

Brain, blood vessels, kidneys, peripheral and autonomic nerves, retina, skin |

Brain satiety centers with increased proneness to obesity |

The inclusion of AD within the spectrum of insulin-resistance diseases opens doors for endocrinologists and specifically diabetologists to detect disease earlier in patients with overlapping organ-system involvement and also helps design and monitor the effects of treatment. The wealth of clinical, translational, and basic science data accrued by experts in the field could be extended to AD to accelerate the development of programs to better control and possibly cure AD. Similarly, the clustering of other insulin-resistance diseases, such as metabolic syndrome, NAFLD, and polycystic ovarian disease, under one analytical roof could lead to better management of these diseases and also increase the likelihood that their causes could be found.

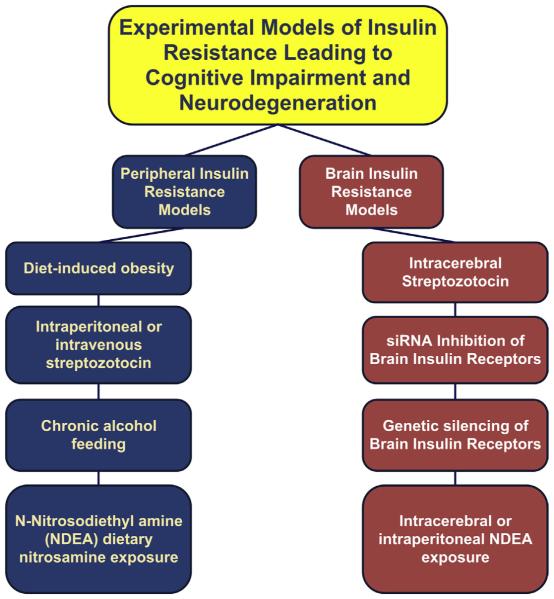

Experimental Evidence that Type 3 Diabetes = Sporadic AD

Experimental intracerebroventricular injections of streptozotocin, a prodiabetes drug, produce deficits in brain energy metabolism,48 impairments in spatial learning and memory, brain insulin resistance, brain insulin deficiency, and AD-type neurodegeneration but not diabetes mellitus.48,49 In contrast, intraperitoneal or intravenous administration of streptozotocin causes diabetes mellitus with mild hepatic steatosis and modest degrees of neurodegeneration.50,51 Therefore, these experiments unequivocally demonstrate that brain diabetes (type 3) can occur independent of T1DM and T2DM and vice versa (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Experimental models of peripheral and brain insulin resistance that lead to neurodegeneration. siRNA, small interfering RNA.

Because streptozotocin is a nitrosamine-related toxin, which may be highly relevant to its overall effects, the specific consequences of brain insulin and IGF resistance are not tested by models generated with this and related compounds. To address this point, further studies were performed using small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplex molecules to silence insulin or IGF receptor expression in the brain.52 This approach avoided the genotoxic and nitrosative damage produced by streptozotocin.50 The inhibition of brain insulin and IGF receptor expression with siRNA molecules was found to be sufficient to cause cognitive impairment and hippocampal degeneration with AD-type impairments in protein and gene expression.52 However, the phenotype was mild compared with the effects of streptozotocin. Therefore, oxidative and nitrosative damage may also be needed to produce a model that is entirely reflective of sporadic AD in humans.

Metabolic Deficits in AD: the Starving Brain

Insulin and IGF signaling regulate glucose utilization and ATP production in the brain. In AD, deficits in cerebral glucose utilization and metabolism occur early and before cognitive decline.53 Therefore, impairments in brain insulin signaling are probably pivotal to AD pathogenesis.36 Oxidative stress stemming from insulin resistance or other superimposed diseases can damage mitochondria, further impairing electron transport and ATP production. In addition, oxidative stress activates proinflammatory networks that cause organelle dysfunction; disinhibits proapoptosis mechanisms; stimulates AβPP expression54 and cleavage to neurotoxic fibrils55; and activates GSK-3β, which promotes tau phosphorylation (Table 3).15,35,56

Table 3.

Role of insulin resistance or insulin deficiency in the molecular and pathologic features of AD

| Alzheimer Pathology | Role of Insulin Resistance/Deficiency |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Phospho-tau neuronal cytoskeletal lesions |

Increased activation of GSK-3b caused by inhibition of insulin signaling and increased oxidative stress |

|

| |

| Amyloid pathology | Formation of toxic amyloid-beta soluble oligomeric fibrils |

|

| |

| Cell injury/death | Activation of proapoptosis pathways; inhibition of prosurvival mechanisms; increased endoplasmic reticulum, oxidative, and nitrosative stress; macromolecular adducts |

|

| |

| Impaired glucose utilization | Reduced glucose uptake, impaired GLUT4 function, reduced signaling downstream of the insulin receptor through IRS, PI3K, and Akt |

|

| |

| Impaired learning and memory | Inhibition of growth pathways needed for synapse formation and remodeling, reduced cholinergic and other neurotransmitter functions, impaired neurogenesis |

|

| |

| Microvascular disease | Hyperinsulinemia in T2DM, possibly local insulin resistance |

|

| |

| White matter atrophy | Cerebral microvascular disease, inhibition of myelin maintenance by oligodendrocytes |

|

| |

| Cholinergic functional deficits | Inhibition of choline acetyltransferase expression, which is regulated by insulin/IGF-1 |

|

| |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction | Oxidative stress-induced DNA damage leading to reduced ATP production and increased levels of reactive oxygen species |

|

| |

| Neuroinflammation | Activation of proinflammatory cytokines |

The glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) mediates glucose uptake in the brain,57 which is abundantly expressed along with insulin receptors in the medial temporal lobe and other targets of AD.15,20 Insulin stimulates GLUT4 mRNA expression and GLUT4 protein trafficking from the Golgi to the plasma membrane where it engages in glucose uptake. In AD, because GLUT4 expression is preserved,36 deficits in brain glucose utilization and energy metabolism vis-á-vis brain insulin/IGF resistance could be mediated in part by functional impairments in GLUT4 (ie, posttranslational mechanisms responsible for GLUT4 trafficking to the plasma membrane).

Chronic Ischemic Cerebral Microvascular Disease

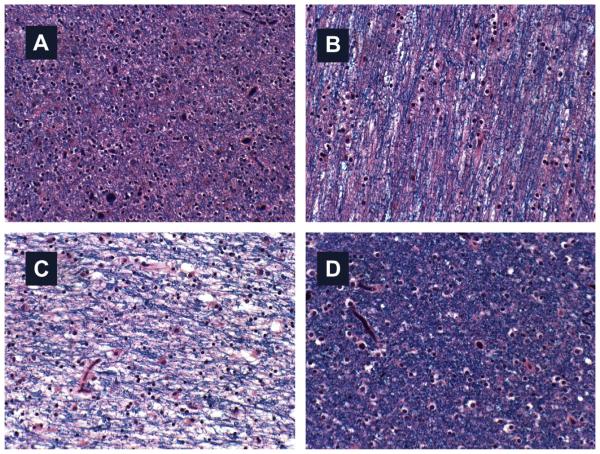

Cerebral microvascular disease is a consistent feature of AD, and recognized mediator of cognitive impairment (Fig. 7). Postmortem studies demonstrated similar degrees of dementia in people with severe classical AD and those with moderate AD plus chronic ischemic encephalopathy. The ischemic injury mainly consists of multifocal small infarcts and leukoaraiosis (ie, extensive white matter fiber attrition with pallor of myelin staining) and prominent cerebral microvascular disease (see Fig. 7; Fig. 8).58 T2DM and hypertension cause microvascular disease throughout the body, including the brain. Evidence that microvascular disease contributes to neurodegeneration was suggested by the finding that the medial temporal lobe, which houses the hippocampus, undergoes progressive atrophy with advancing stages of T2DM.59 Perhaps the regular finding of chronic ischemic leukoencephalopathy (white matter atrophy and fiber degeneration) with microvascular disease in AD is just another manifestation of brain diabetes. It is noteworthy that besides the impairments in brain glucose metabolism, white matter atrophy is one of the earliest abnormalities in AD.60

Fig. 7.

Microvascular disease contributes to cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration in AD. (A) Arteriolosclerosis and capillary sclerosis are associated with fibrotic thickening of vessel walls and extreme narrowing of the lumens (arrow). (B) Arteriosclerosis results in chronic ischemic injury with rarefaction of white matter fibers (loss of dense Luxol fast blue myelin staining in vicinity of blood vessels [arrow]). Note fibrosis of vessel walls and perivascular microhemorrhages in center. These abnormalities reflect increased stiffness and reduce vascular compliance, together with weakness and leakiness of vascular walls. (C) Marked fibrotic thickening and damage to vessel wall caused by destruction (clearing) of the media. Tissue surrounding vessel in center is lost. Adjacent myelin is stained blue (Luxol fast blue). (D) Large area of perivascular tissue loss and further pallor adjacent to lacunar infarct. Note small vessels with tiny lumens and rigid fibrotic vessels in the middle of the perivascular lacunar infarct ([A–D] Luxol fast blue, hematoxylin-eosin).

Fig. 8.

White matter fiber loss in AD. Myelin is produced by oligodendrocytes, which are insulin and IGF-1 responsive. Insulin resistance impairs oligodendrocyte function. In AD, brain insulin/IGF-1 resistance develop early in the course of neurodegeneration, and the earliest abnormalities include impairments in glucose metabolism and white matter atrophy. White matter from the (A) anterior frontal, (B) posterior frontal, (C) parietal, and (D) occipital lobes (Luxol fast blue). The normal appearance of staining is depicted in (D), an area least affected by AD. The pink coloration in (A, B) reflect loss of myelin and myelinated fibers. The extreme pallor of myelin staining in (C) corresponds to the severity of neurodegeneration and extensive fiber loss.

Hyperinsulinemia causes progressive injury to microvessels. Chronic microvascular injury is characterized by reactive proliferation of endothelial cells, thickening of the intima, fibrosis of the media, and narrowing of the lumens. Mural scarring reduces vascular compliance and compromises blood flow and nutrient delivery, particularly in periods of high metabolic demand. Moreover, weakened and damaged blood vessels are leaky and permeable to toxins,61,62 which together could contribute to increased frequencies of microhemorrhage and perivascular white matter tissue loss in T2DM and AD. Therefore, hyperinsulinemia ultimately produces a state of chronic hypoperfusion with toxic/metabolic/ischemic tissue degeneration in the brain. These pathologic processes have not received adequate attention, and their mechanistic links to cognitive impairment in diabetes and AD are only in the rudimentary stages of investigation.

BRAIN METABOLIC DERANGEMENTS IN OTHER NEURODEGENERATIVE DISEASES

Advances in neuroimaging, including positron emission tomography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), functional MRI, and magnetic spectroscopy, together with molecular and biochemical biomarkers have helped demonstrate the common themes surrounding disease mechanisms among clinically and pathologically diverse sets of neurodegenerative diseases.63–65 For example, like AD, other major neurodegenerative diseases are associated with deficits in brain metabolism. Parkinson-dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), frontotemporal lobar dementia, motor neuron disease, and multiple systems atrophy are all associated with brain accumulations of misfolded ubiquitinated proteins (often cytoskeletal) and increased levels of oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, autophagy, mitochondrial dysfunction, apoptosis, and necrosis.66–70 Parkinson disease (PD) has epidemiologic links to diabetes mellitus,45 and experimental PD is associated with insulin resistance in the basal ganglia.71 Finally, impairments in insulin and IGF signaling exist in human brains with PD or DLB, although the nature and distribution of abnormalities differ from those in AD.72 Therefore, many sporadic human neurodegenerative diseases could potentially be approached from diagnostic and therapeutic perspectives through knowledge gained in endocrinology and specifically diabetology.

UNDERLYING CAUSES OF BRAIN INSULIN RESISTANCE IN AD

Aging

Insulin and IGF resistance increase with aging, whereas longevity is associated with the preservation of insulin/IGF responsiveness.73–75 Furthermore, evidence suggests that chronic stress over a lifespan damages cells because of excessive signaling through insulin/IGF-1 receptors.76 Correspondingly, neuronal overexpression of IRS2 leads to increased fat mass, insulin resistance, and glucose intolerance with aging.77 These findings suggest that chronic overuse of insulin/IGF signaling networks, which occurs with hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance, accelerates aging.

Declines in growth hormone levels and metabolism also promote aging because of the anabolic deficiencies that accelerate metabolic dysfunction.78 Because growth hormone deficiency promotes obesity79 and obesity promotes insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, aging-associated declines in growth hormone could be a cause of insulin resistance.80 Because this concept is broadly applicable to insulin resistance–related degenerative diseases, efforts should be made to improve our understanding of cellular aging, with the goal of preventing or delaying the onset of neurodegeneration.

Arguments could be made that insulin resistance, cognitive impairment, and AD are inevitable consequences of aging81 because aging-associated chronic low-grade inflammation82,83 causes insulin resistance.83,84 Because inflammation and insulin resistance increase oxidative stress, over time, reactive oxygen species and advanced glycation end-products accumulate, driving mitochondrial dysfunction, DNA damage, and cell death cascades,80 which are pivotal to aging-associated cognitive impairment and brain atrophy.

On the other hand, opposing arguments offer an alternative perspective and suggest that other intrinsic host factors, lifetime exposures, and lifestyle choices dictate the quality of aging and propensity to develop insulin-resistance diseases. An excellent example of this phenomenon exists with respect to postpolio syndrome, in which people who recovered from childhood poliomyelitis exhibit high rates of motor neuron disease as middle-aged adults.85,86 During childhood, recovery from poliomyelitis was enabled by the vigorous regenerative and reparative activities of the youthful plastic central nervous system (CNS). However, with aging, the regenerative capacity of the CNS declines. Individuals develop postpolio motor neuron disease because the underlying previously damaged motor neuron system gets exposed, resulting in significant weakness caused by denervation myopathy.87,88 In contrast, aging of the previously undamaged CNS results in mild weakness and reduced mobility; this suggests that chronic enrichment and protection of neuronal circuitry may be required to maintain excellent brain function throughout the normal human lifespan.

Lifestyle Choices and Aging

Obesity, T2DM, NAFLD/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), metabolic syndrome, and AD have grown in prevalence to epidemic proportions in many societies.29,89,90 In recent years, countries throughout the world have witnessed rapid increases in the prevalence rates of insulin-resistance diseases and their consequences in nonaged individuals, including adolescents and children.81 These trends have been linked to obesity and sedentary lifestyles. Because the spectra of insulin resistance–related diseases are nearly identical across different age groups, it could be argued that certain lifestyles, habits, and behaviors cause disease by accelerating aging. By the same token, lifestyle modifications could potentially retard aging and defer or prevent aging-associated insulin-resistance diseases, including neurodegeneration.

Obesity and Cognitive Impairment

Obesity significantly increases the risk for cognitive impairment and leads to brain insulin resistance because of the disruption of homeostatic mechanisms.11,91–93 Concerns about obesity’s effects on the brain arose from studies showing an increased risk for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or AD-type dementia in individuals with glucose intolerance, deficits in insulin secretion, T2DM, obesity/dyslipidemic disorders, or NASH.20,94–96 Other studies correlated obesity with deficits in executive function96,97 and eventual development of AD.98 These concepts were confirmed in experimental animal models of diet-induced obesity with T2DM.47,91,99,100 Perhaps the most convincing evidence that obesity contributes to cognitive impairment was provided by studies showing that weight-loss reversal of insulin resistance improves cognitive performance101,102 and neuropsychiatric function103 and that adherence to Mediterranean diets reduces metabolic risk for AD.104

T2DM

The molecular and biochemical abnormalities in AD mimic the effects of T2DM on skeletal muscle and NASH on liver. Epidemiologic and longitudinal studies demonstrated increased risks for MCI or AD in people with glucose intolerance, T2DM, obesity/dyslipidemic disorders, or deficits in insulin secretion.105–107 More recently, investigators linked increased rates of cognitive impairment to chronic hyperglycemia,108 which precedes the diagnosis of T2DM. Similarly, postmortem studies revealed that peripheral insulin resistance contributes to cognitive impairment and AD progression,109,110 whereas experimental studies showed that diet-induced obesity with T2DM leads to deficits in spatial learning and memory,99 brain atrophy with brain insulin resistance, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and deficits in cholinergic function.91,111

NAFLD/NASH

Several studies have shown that cognitive impairment and neuropsychiatric dysfunction occur with steatohepatitis caused by obesity, alcohol abuse, chronic hepatitis C virus infection, Reyes syndrome, or nitrosamine exposure.111–114 Mechanistically, steatohepatitis (ie, inflammation with fatty liver disease) increases ER stress, oxidative damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and lipid peroxidation, which together drive hepatic insulin resistance.93 Hepatic insulin resistance dysregulates lipid metabolism and promotes lipolysis,115 which increases the production of toxic lipids, including ceramides, which further impair insulin signaling, mitochondrial function, and cell viability.93,116,117 Liver disease worsens as ER stress and mitochondrial dysfunction exacerbate insulin resistance,11 lipolysis, and ceramide accumulation.118–120

Experimental models of NAFLD with T2DM and visceral obesity are associated with brain atrophy, neurodegeneration, and cognitive impairment.56,91,100,111,114 In humans with NASH, the rates of neuropsychiatric disease, including depression and anxiety,121 and the risks for developing cognitive impairment122 are increased. In fact, cognitive impairment and neuropsychiatric dysfunction correlate more with steatohepatitis and insulin resistance than obesity or T2DM.123,124 Therefore, the potential roles of steatohepatitis and hepatic insulin resistance in relation to neurodegeneration must be considered. To this end, the author and colleagues hypothesized that increased levels of cytotoxic ceramides generated in liver (or visceral adipose tissue) could cause neurodegeneration.56,100,111,114 In humans and experimental models with steatohepatitis, ceramide gene expression and ceramide levels are increased regardless of the cause.19,20,91,125–128 Correspondingly, CNS exposures to cytotoxic ceramides cause AD-type molecular and biochemical abnormalities in vitro129,130 and cognitive-motor deficits, brain insulin resistance, oxidative stress, metabolic dysfunction, and neurodegeneration with features similar to AD in vivo.128 Ex vivo treatment of frontal lobe slice cultures with long-chain ceramide-containing plasma from obese rats with steatohepatitis produces neurotoxic responses with impairments in viability and mitochondrial function.125 This concept illustrates how peripheral insulin-resistance diseases might cause or contribute to cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration.

Metabolic Syndrome

Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of disease processes that pivots around insulin resistance, visceral obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.131 Metabolic syndrome increases the risk for coronary artery disease, atherosclerosis, and T2DM and is frequently associated with NAFLD/NASH, proinflammatory and prothrombotic states, and sleep apnea.131 Studies have linked peripheral insulin resistance,132 visceral obesity,133 and metabolic syndrome134–136 to brain atrophy, cognitive impairment, and declines in executive function. These associations sound an alarm in light of the recent increases in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome among adults and children.137 If T2DM, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and NAFLD/NASH could actually be demonstrated to serve as cofactors in the pathogenesis and progression of neurodegeneration, then aggressive efforts would be needed to treat and prevent the full spectrum of systemic insulin-resistance diseases. Accordingly, antihyperglycemic or insulin sensitizer agents have already been shown to reduce AD clinical manifestations and pathology.56,138–143

SUMMARY

Brain insulin/IGF resistance initiates a cascade of progressive oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, impaired cell survival, mitochondrial dysfunction, dysregulated lipid metabolism, and ER stress. Continued compromise of neuronal and glial functions causes cognitive impairment and the eventual development of neurodegeneration. Because many of the molecular and cellular abnormalities in AD exist in systemic/peripheral insulin resistance, such as in obesity, T2DM, and NAFLD/NASH, common mechanisms of insulin and IGF resistance should be investigated. By regarding these clinically diverse diseases as fundamentally related on molecular, biochemical, and perhaps etiologic bases, their clustering beneath an umbrella term of insulin resistance spectrum disorders could accelerate the discovery of new treatments and improve the understanding of disease pathogenesis and progression.

Fig. 4.

Left: Coronal section through the right cerebral hemisphere showing extreme atrophy of the hippocampus, thalamus, and white matter, with compensatory enlargement of the ventricles. Right: Histologic section through the hippocampus stained to illustrate abundant senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles replacing the normal architecture (Bielschowsky silver impregnation) (original magnification ×100).

KEY POINTS.

Alzheimer disease is a neurodegenerative disease associated with impairments in glucose metabolism and insulin resistance in the brain.

Many of the molecular and biochemical defects in Alzheimer disease are identical to those in either type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus as well as other insulin-resistance disease states.

Peripheral insulin-resistance disease states, including diabetes, obesity, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, are associated with cognitive impairment and can exacerbate Alzheimer disease, (ie, cause it to progress).

Therapeutic measures used for diabetes show efficacy in the early and moderate stages of Alzheimer disease.

Endocrinologists and diabetologists should play a larger role in the early detection and monitoring of cognitive impairment in obese and/or diabetic patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources are grants AA-11431 and AA-12908 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The author has no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Best CH, Scott DA. The preparation of insulin. J Biol Chem. 1923;57:709–23. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth J, Qureshi S, Whitford I, et al. Insulin’s discovery: new insights on its ninetieth birthday. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28(4):293–304. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilchrist JA, Best CH, Banting FG. Observations with insulin on Department of Soldiers’ Civil Re-Establishment Diabetics. Can Med Assoc J. 1923;13(8):565–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gualandi-Signorini AM, Giorgi G. Insulin formulations–a review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2001;5(3):73–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heinemann L, Richter B. Clinical pharmacology of human insulin. Diabetes Care. 1993;16(Suppl 3):90–100. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.3.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dave N, Hazra P, Khedkar A, et al. Process and purification for manufacture of a modified insulin intended for oral delivery. J Chromatogr A. 2008;1177(2):282–6. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freiherr J, Hallschmid M, Frey WH, 2nd, et al. Intranasal insulin as a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease: a review of basic research and clinical evidence. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(7):505–14. doi: 10.1007/s40263-013-0076-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ott V, Benedict C, Schultes B, et al. Intranasal administration of insulin to the brain impacts cognitive function and peripheral metabolism. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(3):214–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plum MB, Sicat BL, Brokaw DK. Newer insulin therapies for management of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Consult Pharm. 2003;18(5):454–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeyda M, Stulnig TM. Obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance–a mini-review. Gerontology. 2009;55(4):379–86. doi: 10.1159/000212758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Capeau J. Insulin resistance and steatosis in humans. Diabetes Metab. 2008;34(6):649–57. doi: 10.1016/S1262-3636(08)74600-7. Pt 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dai Z, Wu F, Yeung EW, et al. IGF-IEc expression, regulation and biological function in different tissues. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2010;20(4):275–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matheny RW, Jr, Nindl BC, Adamo ML. Minireview: mechano-growth factor: a putative product of IGF-I gene expression involved in tissue repair and regeneration. Endocrinology. 2010;151(3):865–75. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuemmerle JF. Insulin-like growth factors in the gastrointestinal tract and liver. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2012;41(2):409–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2012.04.018. vii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de la Monte SM, Wands JR. Review of insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression, signaling, and malfunction in the central nervous system: relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;7(1):45–61. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-7106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D’Ercole AJ, Ye P. Expanding the mind: insulin-like growth factor I and brain development. Endocrinology. 2008;149(12):5958–62. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freude S, Schilbach K, Schubert M. The role of IGF-1 receptor and insulin receptor signaling for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: from model organisms to human disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2009;6(3):213–23. doi: 10.2174/156720509788486527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeger M, Popken G, Zhang J, et al. Insulin-like growth factor type 1 receptor signaling in the cells of oligodendrocyte lineage is required for normal in vivo oligodendrocyte development and myelination. Glia. 2007;55(4):400–11. doi: 10.1002/glia.20469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de la Monte SM, Longato L, Tong M, et al. The liver-brain axis of alcohol-mediated neurodegeneration: role of toxic lipids. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6(7):2055–75. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6072055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de la Monte SM, Longato L, Tong M, et al. Insulin resistance and neurodegeneration: roles of obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10(10):1049–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gronke S, Clarke DF, Broughton S, et al. Molecular evolution and functional characterization of Drosophila insulin-like peptides. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(2):e1000857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shanik MH, Xu Y, Skrha J, et al. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia: is hyperinsulinemia the cart or the horse? Diabetes Care. 2008;31(Suppl 2):S262–8. doi: 10.2337/dc08-s264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dankner R, Chetrit A, Shanik MH, et al. Basal-state hyperinsulinemia in healthy normoglycemic adults is predictive of type 2 diabetes over a 24-year follow-up: a preliminary report. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(8):1464–6. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia RG, Rincon MY, Arenas WD, et al. Hyperinsulinemia is a predictor of new cardiovascular events in Colombian patients with a first myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2011;148(1):85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kasai T, Miyauchi K, Kajimoto K, et al. The adverse prognostic significance of the metabolic syndrome with and without hypertension in patients who underwent complete coronary revascularization. J Hypertens. 2009;27(5):1017–24. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32832961cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agnoli C, Berrino F, Abagnato CA, et al. Metabolic syndrome and postmenopausal breast cancer in the ORDET cohort: a nested case-control study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;20(1):41–8. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faulds MH, Dahlman-Wright K. Metabolic diseases and cancer risk. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24(1):58–61. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32834e0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colonna SV, Douglas Case L, Lawrence JA. A retrospective review of the metabolic syndrome in women diagnosed with breast cancer and correlation with estrogen receptor. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131(1):325–31. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1790-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de la Monte SM, Neusner A, Chu J, et al. Epidemiological trends strongly suggest exposures as etiologic agents in the pathogenesis of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes mellitus, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17(3):519–29. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cummings JL. Definitions and diagnostic criteria. 3rd Informa UK Limited; London: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gustaw-Rothenberg K, Lerner A, Bonda DJ, et al. Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease: past, present and future. Biomark Med. 2010;4(1):15–26. doi: 10.2217/bmm.09.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, et al. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416(6880):535–9. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frolich L, Blum-Degen D, Bernstein HG, et al. Brain insulin and insulin receptors in aging and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm. 1998;105(4–5):423–38. doi: 10.1007/s007020050068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoyer S. Glucose metabolism and insulin receptor signal transduction in Alzheimer disease. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;490(1–3):115–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rivera EJ, Goldin A, Fulmer N, et al. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and function deteriorate with progression of Alzheimer’s disease: link to brain reductions in acetylcholine. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;8(3):247–68. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-8304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steen E, Terry BM, Rivera EJ, et al. Impaired insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and signaling mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease–is this type 3 diabetes? J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;7(1):63–80. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-7107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de la Monte SM. Therapeutic targets of brain insulin resistance in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2012;E4:1582–605. doi: 10.2741/482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de la Monte SM, Re E, Longato L, et al. Dysfunctional pro-ceramide, ER stress, and insulin/IGF signaling networks with progression of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;30(0):S217–29. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caselli RJ, Chen K, Lee W, et al. Correlating cerebral hypometabolism with future memory decline in subsequent converters to amnestic pre-mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(9):1231–6. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mosconi L, Pupi A, De Leon MJ. Brain glucose hypometabolism and oxidative stress in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1147:180–95. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Langbaum JB, Chen K, Caselli RJ, et al. Hypometabolism in Alzheimer-affected brain regions in cognitively healthy Latino individuals carrying the apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(4):462–8. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoyer S, Nitsch R. Cerebral excess release of neurotransmitter amino acids subsequent to reduced cerebral glucose metabolism in early-onset dementia of Alzheimer type. J Neural Transm. 1989;75(3):227–32. doi: 10.1007/BF01258634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoyer S, Nitsch R, Oesterreich K. Predominant abnormality in cerebral glucose utilization in late-onset dementia of the Alzheimer type: a cross-sectional comparison against advanced late-onset and incipient early-onset cases. J Neural Transm Park Dis Dement Sect. 1991;3(1):1–14. doi: 10.1007/BF02251132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Talbot K, Wang HY, Kazi H, et al. Demonstrated brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease patients is associated with IGF-1 resistance, IRS-1 dysregulation, and cognitive decline. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(4):1316–38. doi: 10.1172/JCI59903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salcedo I, Tweedie D, Li Y, et al. Neuroprotective and neurotrophic actions of glucagon-like peptide-1: an emerging opportunity to treat neurodegenerative and cerebrovascular disorders. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166(5):1586–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01971.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piriz J, Muller A, Trejo JL, et al. IGF-I and the aging mammalian brain. Exp Gerontol. 2011;46(2–3):96–9. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mattson MP. The impact of dietary energy intake on cognitive aging. Front Aging Neurosci. 2010;2:5. doi: 10.3389/neuro.24.005.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weinstock M, Shoham S. Rat models of dementia based on reductions in regional glucose metabolism, cerebral blood flow and cytochrome oxidase activity. J Neural Transm. 2004;111(3):347–66. doi: 10.1007/s00702-003-0058-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lester-Coll N, Rivera EJ, Soscia SJ, et al. Intracerebral streptozotocin model of type 3 diabetes: relevance to sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9(1):13–33. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bolzan AD, Bianchi MS. Genotoxicity of streptozotocin. Mutat Res. 2002;512(2–3):121–34. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(02)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koulmanda M, Qipo A, Chebrolu S, et al. The effect of low versus high dose of streptozotocin in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascilularis) Am J Transplant. 2003;3(3):267–72. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de la Monte SM, Tong M, Bowling N, et al. si-RNA inhibition of brain insulin or insulin-like growth factor receptors causes developmental cerebellar abnormalities: relevance to fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Mol Brain. 2011;4:13. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-4-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoyer S. Causes and consequences of disturbances of cerebral glucose metabolism in sporadic Alzheimer disease: therapeutic implications. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2004;541:135–52. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8969-7_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen GJ, Xu J, Lahousse SA, et al. Transient hypoxia causes Alzheimer-type molecular and biochemical abnormalities in cortical neurons: potential strategies for neuroprotection. J Alzheimers Dis. 2003;5(3):209–28. doi: 10.3233/jad-2003-5305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsukamoto E, Hashimoto Y, Kanekura K, et al. Characterization of the toxic mechanism triggered by Alzheimer’s amyloid-beta peptides via p75 neurotrophin receptor in neuronal hybrid cells. J Neurosci Res. 2003;73(5):627–36. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de la Monte SM, Tong M, Lester-Coll N, et al. Therapeutic rescue of neurodegeneration in experimental type 3 diabetes: relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;10(1):89–109. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gonzalez-Sanchez JL, Serrano-Rios M. Molecular basis of insulin action. Drug News Perspect. 2007;20(8):527–31. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2007.20.8.1157615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Etiene D, Kraft J, Ganju N, et al. Cerebrovascular pathology contributes to the heterogeneity of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 1998;1(2):119–34. doi: 10.3233/jad-1998-1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Korf ES, White LR, Scheltens P, et al. Brain aging in very old men with type 2 diabetes: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(10):2268–74. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.de la Monte SM. Quantitation of cerebral atrophy in preclinical and end-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1989;25(5):450–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.410250506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kincaid-Smith P. Hypothesis: obesity and the insulin resistance syndrome play a major role in end-stage renal failure attributed to hypertension and labelled ’hypertensive nephrosclerosis’. J Hypertens. 2004;22(6):1051–5. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200406000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matsumoto H, Nakao T, Okada T, et al. Insulin resistance contributes to obesity-related proteinuria. Intern Med. 2005;44(6):548–53. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.44.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.O’Brien JT. Role of imaging techniques in the diagnosis of dementia. Br J Radiol. 2007;80:S71–7. doi: 10.1259/bjr/33117326. Spec No 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Poljansky S, Ibach B, Hirschberger B, et al. A visual [18F]FDG-PET rating scale for the differential diagnosis of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;261(6):433–46. doi: 10.1007/s00406-010-0184-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Teune LK, Bartels AL, de Jong BM, et al. Typical cerebral metabolic patterns in neurodegenerative brain diseases. Mov Disord. 2010;25(14):2395–404. doi: 10.1002/mds.23291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nijholt DA, De Kimpe L, Elfrink HL, et al. Removing protein aggregates: the role of proteolysis in neurodegeneration. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18(16):2459–76. doi: 10.2174/092986711795843236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Uehara T. Accumulation of misfolded protein through nitrosative stress linked to neurodegenerative disorders. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9(5):597–601. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hol EM, Fischer DF, Ovaa H, et al. Ubiquitin proteasome system as a pharmacological target in neurodegeneration. Expert Rev Neurother. 2006;6(9):1337–47. doi: 10.1586/14737175.6.9.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kahle PJ, Haass C. How does parkin ligate ubiquitin to Parkinson’s disease? EMBO Rep. 2004;5(7):681–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Turner BJ, Atkin JD. ER stress and UPR in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6(1):79–86. doi: 10.2174/156652406775574550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Morris JK, Seim NB, Bomhoff GL, et al. Effects of unilateral nigrostriatal dopamine depletion on peripheral glucose tolerance and insulin signaling in middle aged rats. Neurosci Lett. 2011;504(3):219–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tong M, Dong M, de la Monte SM. Brain insulin-like growth factor and neurotrophin resistance in Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies: potential role of manganese neurotoxicity. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16(3):585–99. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sato N, Takeda S, Uchio-Yamada K, et al. Role of insulin signaling in the interaction between Alzheimer disease and diabetes mellitus: a missing link to therapeutic potential. Curr Aging Sci. 2011;4(2):118–27. doi: 10.2174/1874609811104020118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Holzenberger M. Igf-I signaling and effects on longevity. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Pediatr Program. 2011;68:237–45. doi: 10.1159/000325914. [discussion: 246–9] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schuh AF, Rieder CM, Rizzi L, et al. Mechanisms of brain aging regulation by insulin: implications for neurodegeneration in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. ISRN Neurol. 2011;2011:306905. doi: 10.5402/2011/306905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Valentini S, Cabreiro F, Ackerman D, et al. Manipulation of in vivo iron levels can alter resistance to oxidative stress without affecting ageing in the nematode C. elegans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2012;133(5):282–90. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zemva J, Udelhoven M, Moll L, et al. Neuronal overexpression of insulin receptor substrate 2 leads to increased fat mass, insulin resistance, and glucose intolerance during aging. Age (Dordr) 2012;35(5):1881–97. doi: 10.1007/s11357-012-9491-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Castilla-Cortazar I, Garcia-Fernandez M, Delgado G, et al. Hepatoprotection and neuroprotection induced by low doses of IGF-II in aging rats. J Transl Med. 2011;9:103. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Luque RM, Lin Q, Cordoba-Chacon J, et al. Metabolic impact of adult-onset, iso-lated, growth hormone deficiency (AOiGHD) due to destruction of pituitary somatotropes. PloS One. 2011;6(1):e15767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Srikanth V, Westcott B, Forbes J, et al. Methylglyoxal, cognitive function and cerebral atrophy in older people. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;68(1):68–73. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Williamson R, McNeilly A, Sutherland C. Insulin resistance in the brain: an old-age or new-age problem? Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;84(6):737–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Oxenkrug G. Interferon-gamma - inducible inflammation: contribution to aging and aging-associated psychiatric disorders. Aging Dis. 2011;2(6):474–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Horrillo D, Sierra J, Arribas C, et al. Age-associated development of inflammation in Wistar rats: effects of caloric restriction. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2011;117(3):140–50. doi: 10.3109/13813455.2011.577435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cai D, Liu T. Inflammatory cause of metabolic syndrome via brain stress and NF-kappaB. Aging (Albany NY) 2012;4(2):98–115. doi: 10.18632/aging.100431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Birk TJ. Poliomyelitis and the post-polio syndrome: exercise capacities and adaptation–current research, future directions, and widespread applicability. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25(4):466–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jubelt B, Cashman NR. Neurological manifestations of the post-polio syndrome. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1987;3(3):199–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gordon T, Hegedus J, Tam SL. Adaptive and maladaptive motor axonal sprouting in aging and motoneuron disease. Neurol Res. 2004;26(2):174–85. doi: 10.1179/016164104225013806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dalakas MC. Pathogenetic mechanisms of post-polio syndrome: morphological, electrophysiological, virological, and immunological correlations. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;753:167–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb27543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chiang DJ, Pritchard MT, Nagy LE. Obesity, diabetes mellitus, and liver fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;300(5):G697–702. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00426.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM. Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(3):274–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lyn-Cook LE, Jr, Lawton M, Tong M, et al. Hepatic ceramide may mediate brain insulin resistance and neurodegeneration in type 2 diabetes and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16(4):715–29. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.de la Monte SM, Wands JR. Alzheimer’s disease is type 3 diabetes: evidence reviewed. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2008;2(6):1101–13. doi: 10.1177/193229680800200619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kraegen EW, Cooney GJ. Free fatty acids and skeletal muscle insulin resistance. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2008;19(3):235–41. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000319118.44995.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Luchsinger JA, Reitz C, Patel B, et al. Relation of diabetes to mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(4):570–5. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.4.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Craft S. Insulin resistance and Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis: potential mechanisms and implications for treatment. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007;4(2):147–52. doi: 10.2174/156720507780362137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lokken KL, Boeka AG, Austin HM, et al. Evidence of executive dysfunction in extremely obese adolescents: a pilot study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2009;5(5):547–52. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gunstad J, Paul RH, Cohen RA, et al. Elevated body mass index is associated with executive dysfunction in otherwise healthy adults. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48(1):57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yaffe K. Metabolic syndrome and cognitive decline. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007;4(2):123–6. doi: 10.2174/156720507780362191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Winocur G, Greenwood CE. Studies of the effects of high fat diets on cognitive function in a rat model. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26(Suppl 1):46–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Moroz N, Tong M, Longato L, et al. Limited Alzheimer-type neurodegeneration in experimental obesity and Type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;15(1):29–44. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-15103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Baker LD, Frank LL, Foster-Schubert K, et al. Aerobic exercise improves cognition for older adults with glucose intolerance, a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22(2):569–79. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Baker LD, Frank LL, Foster-Schubert K, et al. Effects of aerobic exercise on mild cognitive impairment: a controlled trial. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(1):71–9. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bryan J, Tiggemann M. The effect of weight-loss dieting on cognitive performance and psychological well-being in overweight women. Appetite. 2001;36(2):147–56. doi: 10.1006/appe.2000.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gu Y, Luchsinger JA, Stern Y, et al. Mediterranean diet, inflammatory and metabolic biomarkers, and risk of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22(2):483–92. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Martins IJ, Hone E, Foster JK, et al. Apolipoprotein E, cholesterol metabolism, diabetes, and the convergence of risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease and cardiovascular disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11(8):721–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pasquier F, Boulogne A, Leys D, et al. Diabetes mellitus and dementia. Diabetes Metab. 2006;32(5):403–14. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70298-7. Pt 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Whitmer RA. Type 2 diabetes and risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2007;7(5):373–80. doi: 10.1007/s11910-007-0058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Crane PK, Walker R, Hubbard RA, et al. Glucose levels and risk of dementia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(6):540–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nelson PT, Smith CD, Abner EA, et al. Human cerebral neuropathology of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1792(5):454–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Janson J, Laedtke T, Parisi JE, et al. Increased risk of type 2 diabetes in Alzheimer disease. Diabetes. 2004;53(2):474–81. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tong M, Longato L, de la Monte SM. Early limited nitrosamine exposures exacerbate high fat diet-mediated type2 diabetes and neurodegeneration. BMC Endocr Disord. 2010;10(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-10-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Perry W, Hilsabeck RC, Hassanein TI. Cognitive dysfunction in chronic hepatitis C: a review. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(2):307–21. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9896-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Weiss JJ, Gorman JM. Psychiatric behavioral aspects of comanagement of hepatitis C virus and HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2006;3(4):176–81. doi: 10.1007/s11904-006-0013-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Tong M, Neusner A, Longato L, et al. Nitrosamine exposure causes insulin resistance diseases: relevance to type 2 diabetes mellitus, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17(4):827–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kao Y, Youson JH, Holmes JA, et al. Effects of insulin on lipid metabolism of larvae and metamorphosing landlocked sea lamprey, Petromyzon marinus. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1999;114(3):405–14. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1999.7265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Holland WL, Summers SA. Sphingolipids, insulin resistance, and metabolic disease: new insights from in vivo manipulation of sphingolipid metabolism. Endocr Rev. 2008;29(4):381–402. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Langeveld M, Aerts JM. Glycosphingolipids and insulin resistance. Prog Lipid Res. 2009;48(3–4):196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kaplowitz N, Than TA, Shinohara M, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and liver injury. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27(4):367–77. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-991513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Malhi H, Gores GJ. Molecular mechanisms of lipotoxicity in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28(4):360–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1091980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sundar-Rajan S, Srinivasan V, Balasubramanyam M, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress & diabetes. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125(3):411–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Elwing JE, Lustman PJ, Wang HL, et al. Depression, anxiety, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(4):563–9. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221276.17823.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Felipo V, Urios A, Montesinos E, et al. Contribution of hyperammonemia and inflammatory factors to cognitive impairment in minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis. 2011;27(1):51–8. doi: 10.1007/s11011-011-9269-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Schmidt KS, Gallo JL, Ferri C, et al. The neuropsychological profile of alcohol-related dementia suggests cortical and subcortical pathology. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;20(5):286–91. doi: 10.1159/000088306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kopelman MD, Thomson AD, Guerrini I, et al. The Korsakoff syndrome: clinical aspects, psychology and treatment. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44(2):148–54. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.de la Monte SM. Triangulated mal-signaling in Alzheimer’s disease: roles of neurotoxic ceramides, ER stress, and insulin resistance reviewed. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;30:S231–49. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.de la Monte SM, Tong M, Lawton M, et al. Nitrosamine exposure exacerbates high fat diet-mediated type 2 diabetes mellitus, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, and neurodegeneration with cognitive impairment. Mol Neurodegener. 2009;4:54. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.de la Monte SM, Tong M, Nguyen V, et al. Ceramide-mediated insulin resistance and impairment of cognitive-motor functions. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;21(3):967–84. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-091726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Tong M, de la Monte SM. Mechanisms of ceramide-mediated neurodegeneration. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16(4):705–14. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Alessenko AV, Bugrova AE, Dudnik LB. Connection of lipid peroxide oxidation with the sphingomyelin pathway in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:144–6. doi: 10.1042/bst0320144. Pt 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF. Altered lipid metabolism in brain injury and disorders. Subcell Biochem. 2008;49:241–68. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-8831-5_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kassi E, Pervanidou P, Kaltsas G, et al. Metabolic syndrome: definitions and controversies. BMC Med. 2011;9:48. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Tan ZS, Beiser AS, Fox CS, et al. Association of metabolic dysregulation with volumetric brain magnetic resonance imaging and cognitive markers of subclinical brain aging in middle-aged adults: the Framingham Offspring Study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(8):1766–70. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Debette S, Beiser A, Hoffmann U, et al. Visceral fat is associated with lower brain volume in healthy middle-aged adults. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(2):136–44. doi: 10.1002/ana.22062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Hassenstab JJ, Sweat V, Bruehl H, et al. Metabolic syndrome is associated with learning and recall impairment in middle age. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;29(4):356–62. doi: 10.1159/000296071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Frisardi V, Solfrizzi V, Capurso C, et al. Is insulin resistant brain state a central feature of the metabolic-cognitive syndrome? J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;21(1):57–63. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Yates KF, Sweat V, Yau PL, et al. Impact of metabolic syndrome on cognition and brain: a selected review of the literature. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(9):2060–7. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.252759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Burns JM, Honea RA, Vidoni ED, et al. Insulin is differentially related to cognitive decline and atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease and aging. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822(3):333–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Benedict C, Hallschmid M, Schmitz K, et al. Intranasal insulin improves memory in humans: superiority of insulin aspart. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32(1):239–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Craft S, Baker LD, Montine TJ, et al. Intranasal insulin therapy for Alzheimer disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment: a pilot clinical trial. Arch Neurol. 2011;69(1):29–38. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Holscher C. Incretin analogues that have been developed to treat type 2 diabetes hold promise as a novel treatment strategy for Alzheimer’s disease. Recent Pat CNS Drug Discov. 2010;5(2):109–17. doi: 10.2174/157488910791213130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Krikorian R, Eliassen JC, Boespflug EL, et al. Improved cognitive-cerebral function in older adults with chromium supplementation. Nutr Neurosci. 2010;13(3):116–22. doi: 10.1179/147683010X12611460764084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Reger MA, Watson GS, Green PS, et al. Intranasal insulin improves cognition and modulates {beta}-amyloid in early AD. Neurology. 2008;70(6):440–8. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000265401.62434.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Luchsinger JA. Type 2 diabetes, related conditions, in relation and dementia: an opportunity for prevention? J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(3):723–36. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-091687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]