Abstract

We have measured maximal oxygen consumption (O2,max) of mice lacking one or two of the established mouse red-cell CO2 channels AQP1, AQP9, and Rhag. We intended to study whether these proteins, by acting as channels for O2, determine O2 exchange in the lung and in the periphery. We found that O2,max as determined by the Helox technique is reduced by ~16%, when AQP1 is knocked out, but not when AQP9 or Rhag are lacking. This figure holds for animals respiring normoxic as well as hypoxic gas mixtures. To see whether the reduction of O2,max is due to impaired O2 uptake in the lung, we measured carotid arterial O2 saturation (SO2) by pulse oximetry. Neither under normoxic (inspiratory O2 21%) nor under hypoxic conditions (11% O2) is there a difference in SO2 between AQP1null and WT mice, suggesting that AQP1 is not critical for O2 uptake in the lung. The fact that the % reduction of O2,max is identical in normoxia and hypoxia indicates moreover that the limitation of O2,max is not due to an O2 diffusion problem, neither in the lung nor in the periphery. Instead, it appears likely that AQP1null animals exhibit a reduced O2,max due to the reduced wall thickness and muscle mass of the left ventricles of their hearts, as reported previously. We conclude that very likely the properties of the hearts of AQP1 knockout mice cause a reduced maximal cardiac output and thus cause a reduced O2,max, which constitutes a new phenotype of these mice.

Keywords: aquaporin 1, Rhesus-associated glycoprotein, aquaporin 9, maximal oxygen consumption, knockout mice, arterial oxygen saturation, cardiac function of the heart of aquaporin-1-deficient mice

Introduction

Molecular dynamics simulations have shown that AQP1 and AQP4 may conduct CO2 and O2 through their central pore (Hub and de Groot, 2006; Wang et al., 2007; Wang and Tajkhorshid, 2010). This is likely to be also true for some other aquaporins such as AQP9. Experimental evidence for a physiologically meaningful conduction of CO2 by these three proteins has indeed been repeatedly reported (Endeward et al., 2006a; Musa-Aziz et al., 2009; Itel et al., 2012; Geyer et al., 2013). In addition both, molecular dynamics simulations and experimental evidence, have shown that Rhesus proteins conduct CO2 (Endeward et al., 2006a,b, 2008; Musa-Aziz et al., 2009; Hub et al., 2010). However, in our view clear experimental evidence for a physiologically relevant conduction of O2 does not exist for any of these gas channels.

It was our aim in this paper to study the role of these gas channels in systemic O2 transport by measuring maximal oxygen consumption in mice, which had one or two of these channels knocked out. We wanted to test, whether absence of one or two of these channels results in a diffusion problem that limits oxygen uptake. We chose AQP1null, Rhagnull, and AQP9null animals, because these three proteins occur in the red blood cell membrane of the mouse and because all three of them have been shown to act as CO2 channels either in human red cells (Endeward et al., 2006a,b, 2008) or in artificial expression systems (Musa-Aziz et al., 2009; Geyer et al., 2013). It should be appreciated that the principle of our measurement implies that not only lack of potential O2 channels in the red cell membrane, but also lack of such channels in lung tissue and in the tissues of peripheral organs, especially skeletal muscle, could be involved in a limitation of maximal oxygen consumption.

We propose from our data that lack of the three gas channels does not impair oxygen exchange in lung and tissues. However, lack of AQP1, which is associated with a significant reduction of maximal oxygen consumption, likely causes this effect via a reduced maximal cardiac output of the AQP1 knockout animals. In a preceding paper (Al-Samir et al., 2016) we have reported that the left ventricle of the hearts of AQP1-deficent mice has thinner walls than WT mice along with a reduced capillary density.

Methods

Animals

Breeding pairs of heterozygous AQP1 KO mice were kindly provided by Dr. Alan S. Verkman (San Francisco, USA; Ma et al., 1998). They were intercrossed to obtain homozygous AQP1 KO mice and WT littermate controls. AQP9 KO mice were those described by Rojek et al. (2007), Rhagnull mice were those described in Goossens et al. (2010). AQP1/Rhag double KO mice were obtained by intercrossing the two types of KO mice. All strains were occasionally intercrossed with Bl6 from the central animal facility of Hannover Medical School. For PCR genotyping of AQP1-knockout mice we used the DNA from tail snippets and specific the primers

AQP1 W: AAG TCA ACC TCT GCT CAG CTG GG

AQP1 Neo: CTC TAT GGC TTC TGA GGC GGA AAG

AQP1 KO: ACT CAG TGG CTA ACA ACA AAC AGG

in one single PCR reaction.

For PCR genotyping of AQP9-knockout mice with DNA isolated from tail snippets specific primers were used in one single PCR reaction:

F: 5′-AAC TGG GGA TAG TGG GAT TCA AAG A-3′ for AQP9 WT

R: 5′-GCC ACT AGC CAT GTG TTG GTA TTT C-3′ for AQP9 WT and KO

F: 5′-GTG CTA CTT CCA TTT GTC ACG TCC T-3′ for AQP9 KO.

For PCR genotyping of Rhag-knockout mice with DNA isolated from tail snippets specific primers were used in two separate runs:

RhAG WT-F: 5′-CCA TCT CTC CAG CCT AGC AAT TTT C-3′

RhAG WT-R: 5′-AAG TCA GGA AAG AGT CAT TGC ATG G-3

RhAG KO-F: 5′-TGC TAT GAC CAT TGG AAG CAT TGC-3′

RhAG KO-R: 5′-ATT GCA TCG CAT TGT CTG AGT AGG-3′

The absence of the proteins AQP1, AQP9, and Rhag, respectively, has been demonstrated in the single KO mice by Ma et al. (1998), Rojek et al. (2007), and by Goossens et al. (2010).

The mice used in this study had an average weight of 26–31 g and comprised about equal numbers of males and females. For the measurements of resting and maximal oxygen consumption, the groups were weight-matched. Animal experiments were approved by the Niedersächsisches Landesamt für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit (No. 33.12-42502-04-12/0973).

Measurement of animal oxygen consumption

Measurements of animal oxygen consumption were done on conscious mice. Oxygen consumption O2 was measured under two conditions, firstly under “resting” conditions using air at room temperature as the inspiratory gas (O2, rest), secondly under conditions maximizing O2 by using either a (normoxic) mixture of 79% He with 21% O2 (Helox) cooled down to 4°C, yielding normoxic O2,max, or a (hypoxic) mixture of 79% He with 11% O2 and 10% N2 at 4°C and yielding hypoxic O2,max. While the measurement using air represents the classical open system for O2 determination, which measures gas flow together with inflowing and outflowing O2 concentrations, the measurement using He/O2 follows the same principle but maximizes O2 of the animals by withdrawing heat from their lungs. The increased heat loss is caused by the employed gas mixture of 79% He and O2, which conducts heat 4 times more effectively than air (Rosenmann and Morrison, 1974). This heat loss causes a drastic increase in O2, initiated by the thermoregulatory system aiming to maintain core body temperature. Comparisons with protocols for maximal physical exercise and other techniques have shown that this elevated O2 indeed represents the maximal oxygen consumption achieved by the animals, O2,max, which has a value 5–7 times higher than the basal O2 of mice of ~0.03 ml O2/g body weight/min (Segrem and Hart, 1967; Rosenmann and Morrison, 1974; Chappell, 1984; von Engelhardt et al., 2015).

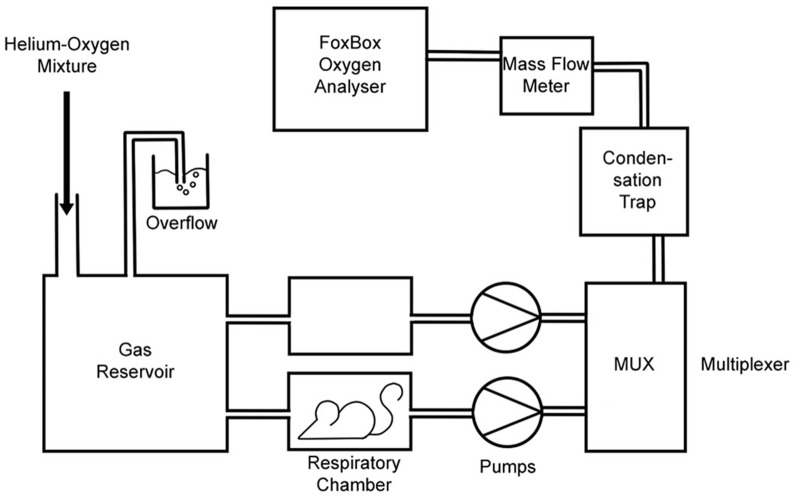

The basic experimental setup for both types of measurement is illustrated in Figure 1. The setup shown allowed us to measure O2 of one mouse that was placed into one of the two respiratory chambers shown. The second chamber was used to obtain a reference gas value. Respiratory chamber dimensions were 15.5 × 8.5 × 10.5 cm. The two pumps drew gas from the gas reservoir at a constant flow rate of 35 l/h through each of the chambers, one with and one without a mouse. The valves of the flow multiplexer (MUX, Sable Systems, North Las Vegas, NV 89032 USA) were controlled by a PC. This provided values of flow rates (MKS Instruments, Munich, Germany; Model: 035CC-01000SVS008) and oxygen concentrations of the outflowing gases (FoxBox; Field Oxygen Analysis System; Sable Systems, North Las Vegas, NV 89032 USA), alternating every 90 s between the two boxes. The gas coming from the empty chamber served as a reference gas for the O2 concentration of air or the He-O2 mixture in the reservoir, respectively, i.e., of the inspiratory gas. The flow meter was calibrated by flushing it at known flow rates either with air or with the suitable helium mixture. O2-values were determined from the difference in O2 concentrations between the gases leaving the two chambers, multiplied by the flow rate of the gas leaving the chamber occupied by the mouse. O2 was normalized for standard (STPD) conditions (0°C, dry).

Figure 1.

Experimental set-up for measurement of maximal oxygen consumption. Pumps draw gas from the gas reservoir through the respiratory chambers and from there via the multiplexer through a water condensation trap and through the flow meter into the oxygen analyzer. For O2, max determination, the gas reservoir contains 21% oxygen/rest He, and the gas reservoir and respiratory chambers are placed into a cold room at 4°C. For resting O2 determination, the gas reservoir contains air, and the entire set-up is placed in room air at 21°C. The empty chamber serves as a control of the inspiratory gas. Usually a third respiratory box was mounted in parallel to the two boxes shown, containing another animal. In this case, the three boxes contained a WT mouse, a KO mouse and no animal, respectively. The gas coming from the empty box was used as a reference gas indicating the O2 concentration in the gas reservoir.

For simultaneous determination of O2 in two mice, a third respiratory box was arranged in parallel to the two boxes indicated in the figure. Then, the flow multiplexer alternated between the three boxes and the gas coming from the empty chamber again served as a reference gas. The same gas flow was sucked continuously from the reservoir through all three chambers. Usually, O2 was measured in parallel for one KO and one WT mouse of similar body weight. Measuring periods for O2 determinations were 45 min, but in the O2,max measurements the maximum was usually reached after a few minutes. It should be noted that the measurements with room air at 21°C were carried out substantially below the thermoneutrality temperature of mice (28°C; Hoevenaars et al., 2014).

In vivo measurement of arterial oxygen saturation and heart and respiratory rate

Carotid artery oxygen (SO2) saturations together with heart rates (HR) and respiratory rates (RR) were measured in vivo with a MouseOX Plus pulse oxymeter (Starr Life Sciences Corp., Oakmont, PA 15139 USA) using ThroatClip sensors size M or S depending on animal size. Data were recorded with the MousOX Plus premium monitoring software. Neck and throat of the animals where shaved to ensure optimal contact of the sensors. The carotid SO2 measurements were performed only on animals respiring 79% He with 21 or 11% O2 at 4°C, using the same setup as employed for O2,max experiments (Figure 1). SO2, HR, and RR were recorded continuously for 20 min for each animal studied. Due to the greater agility of the animals respiring air at 21°C, the sensor did not remain in a stable position, therefore SO2 measurements under resting conditions could not be performed reliably.

Statistical treatment

The results of O2,max and SO2 showed without exception normal distribution when tested according to D'Agostino & Pearson. All pairs of data from WT vs. KO animals were subjected to Student's t-test (unpaired). The software used for both tests was GraphPad Prism 6.01 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, California, USA). Statistical significances were calculated for each pair of WT/KO measurements. N-values given in the tables refer to number of animals studied.

Results

Resting oxygen consumption of conscious mice

Specific resting oxygen consumption of WT mice as measured under exposure of the animals to air at 21°C varies between 0.066 and 0.072 ml O2/g body weight/min for the different mouse strains listed in Table 1 (2nd column). These values, as already discussed above, are about twice the expected basal O2-value for mice of ~0.03 ml/g/min (Segrem and Hart, 1967; Rosenmann and Morrison, 1974; von Engelhardt et al., 2015). The higher O2 may be caused by two factors: (1) the temperature of the measurement, 21°C, is markedly below thermoneutrality, which causes an enhanced metabolism, and (2) the tendency of the animals to exhibit low to moderate physical activity by moving around in their cages (Figure 1). Comparing the resting O2-values of the four mouse strains, it is seen that in two cases, Rhag KO and AQP9 KO, resting O2 is not significantly different between KO and WT, but in the other two cases, AQP1 KO and AQP1-Rhag double KO, O2 is significantly lower in KO mice compared to WT mice. This seems to point to a special property of the AQP1-KO strain.

Table 1.

Results of O2 measurements in KO and WT mice (in ml O2/g/min).

| Normoxia | Hypoxia | Body weight | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O2, rest(air) | O2, max (Helox) | O2, max (He, 11%O2) | ||

| AQP1 WT | 0.066 ± 0.011 (13) | 0.165 ± 0.016 (13) | 0.100 ± 0.013 (12) | 26.7/27.9 g |

| AQP1 KO | 0.053 ± 0.009p2 (12) | 0.142 ± 0.053p1(12) | 0.087 ± 0.009p3 (12) | 25.6/25.9 g |

| Rhag WT | 0.071 ± 0.025 (8) | 0.132 ± 0.016 (8) | 0.081 ± 0.015 (8) | 28.4/28.6 g |

| Rhag KO | 0.077 ± 0.013ns (7) | 0.142 ± 0.010ns (7) | 0.086 ± 0.020ns (7) | 28.6/28.9 g |

| AQP1-Rhag WT | 0.068 ± 0.012 (15) | 0.151 ± 0.025 (15) | 0.093 ± 0.015 (15) | 26.7/27.4 g |

| AQP1-Rhag DKO | 0.050 ± 0.012p5 (14) | 0.130 ± 0.026p4(14) | 0.082 ± 0.017ns (14) | 26.8/26.2 g |

| AQP9 WT | 0.072 ± 0.018 (13) | 0.137 ± 0.014 (13) | 0.090 ± 0.013(13) | 30.7/30.0 g |

| AQP9 KO | 0.063 ± 0.018ns (14) | 0.133 ± 0.018ns(14) | 0.090 ± 0.014ns (14) | 30.8/31.5 g |

O2, rest are measurements of mice at rest in air at 20–24°C, O2,max are measurements of maximal oxygen consumption in the presence of 79% He in the inspiratory gas. Means are given together with SD. Numbers in brackets are number of animals studied. Body weights give on the left numbers for normoxia, on the right for hypoxia. Levels of significance are given for KO- vs. WT-values: ns = not significantly different, p1 = 0.002, p2 = 0.02, p3 = 0.01, p4 = 0.03, p5 = 0.004. Each comparison is between one set of measurements with WT and the corresponding one with KO (DKO) animals.

Maximal oxygen consumption of conscious mice

As described in Methods, the principle employed here to obtain O2,max is to withdraw heat from the animals via their lung. This is achieved by exposing the animals not only to an environment of 4°C but in addition letting them respire a gas mixture containing 79% Helium (plus either 21 or 11% O2), which is also cooled down to 4°C. The excellent heat conduction by He greatly accelerates heat loss and induces an increase in the animals' O2 to the maximum. For normoxic conditions, the 3rd column of Table 1 shows the results for O2,max as obtained by inspiration of Helox at 4°C. It is apparent that only in the case of AQP1-deficient mice, AQP1-KO and AQP1-Rhag double KO, the O2,max-value is markedly and significantly lower in KO than in WT mice, with differences of 16% in both animal strains. Neither Rhag-KO nor AQP9-KO show a difference to WT. We conclude that lack of AQP1 significantly reduces the maximal oxygen consumption under normoxic conditions. Compared to their basal O2 of ~0.03 ml O2/g/min, the WT animals exhibit a 4.5–5.5 times elevated O2,max, which is in excellent agreement with the literature (Segrem and Hart, 1967; Rosenmann and Morrison, 1974; Lechner, 1978; Chappell, 1984).

Under hypoxic conditions, O2,max is in general drastically reduced to 60–65% of the normoxic values due to the hypoxia induced by 11% O2 in the inspired gas. A significant difference between KO- and WT-values is only seen in the case of the AQP1-KO mouse, where O2,max is 15% lower in KO than in WT mice. A similar difference in AQP1-Rhag double-KO mice does not reach statistical significance. In Rhag-KO and AQP9-KO mice there is no difference compared to the respective WT animals. We conclude that, under hypoxia, lack of AQP1 causes a very similar reduction in O2,max as we see it in normoxia. The two other gas channels are without effect.

Heart rates and carotid artery oxygen saturations of conscious mice under conditions of maximal oxygen consumption

Table 2 gives the results of the pulse oximetric determinations of carotid arterial SO2, HR, and RR. In normoxia (2nd and 3rd columns), SO2 has a normal value of 97% both in WT and KO mice. Heart rates are greater than 700 min−1, indicating a maximally increased cardiac activity under Helox respiration (Hoit and Walsh, 2002, p. 284; Segrem and Hart, 1967; Kramer et al., 1993; Desai et al., 1997; Schuler et al., 2010, and personal communication by Beat Schuler). There is no significant difference between HR of KO and WT mice. The same holds for the RR-values.

Table 2.

Results of pulse oximetry in AQP1-KO and WT mice.

| AQP1-WT Normoxia (N = 8) | AQP1-KO Normoxia (N = 6) | AQP1-WT Hypoxia (N = 9) | AQP1-KO Hypoxia (N = 7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO2,a (%) [at O2,max] | 96.8 ± 1.1 | 96.9 ± 1.1ns | 64.2 ± 3.1 | 65.5 ± 2.2ns |

| HR (min−1) [at O2,max] | 770 ± 7 | 717 ± 28ns | 736 ± 11 | 677 ± 31ns |

| RR (min−1) [at O2, max] | 192 ± 13 | 168 ± 10ns | 197 ± 13 | 183 ± 20ns |

SO2, a arterial oxygen saturation (taken above the carotid artery), HR heart rate, RR respiratory rate. All measurements were obtained in about the same time interval as the O2, max measurements, a few minutes after the start of exposure to a helium mixture (21% O2, 79% He in normoxia, 11% O2, 10% N2, 79% He in hypoxia). Given are means ± SD. Statistical significances refer to comparisons of pairs of sets of KO- vs. WT-values (unpaired t-test). Levels of significance are from top down 0.92, 0.12, and 0.17 (3rd vs. 2nd column) and 0.73, 0.11 and 0.58 (5th vs. 4th column). Mean body weights were between 25 and 31 g.

The 4th and 5th columns of Table 2 give the oximetric results under hypoxia. Arterial SO2 is markedly reduced to about 65%, but there is again no difference between KO and WT. Likewise, values of HR and RR are not different between KO and WT; they are also not different from the values under normoxia. In conclusion, AQP1 deficiency does not seem to affect arterial oxygen saturation and heart as well as respiratory rate.

Discussion

Can the hypoxic reduction of O2,max in wildtype animals under hypoxia be fully explained by the reduced arterial SO2?

Since all WT animals can be assumed to have normal cardiac function, it seems likely that the drastically reduced O2,max seen under hypoxia is solely due to the markedly reduced arterial SO2 observed in this condition (Table 2). We discuss in this paragraph, whether this assumption is plausible in view of the existing literature. Judged from the heart rates of the WT animals seen in Table 2, it appears that cardiac activation is close to maximal and identical under normoxia and hypoxia. If indeed cardiac output is identical for WT under normoxia and hypoxia, the reduction of O2 consumption must be exclusively due to a reduced oxygen extraction form arterial blood under hypoxia. On average, WT animals under hypoxia (Table 1) show a O2,max amounting to 63% of O2,max under normoxia. From the arterial O2 saturations given in Table 2 for WT under normoxia and hypoxia, it can be estimated that the diminished O2 consumption under hypoxia is fully explicable by the diminished arterial O2 saturation in hypoxia: if mixed venous SO2 is taken to be about 10% in both normoxic and hypoxic animals, arterio-venous SO2 differences of 87% in normoxia and of 55% in hypoxia are calculated. Indeed, 55 turns out to be 63% of 87, indicating that the difference in O2 extraction fully explains the difference in O2,max. A number of 10% for mixed venous SO2 is realistic in view of measurements performed under maximal aerobic exercise in normoxia and hypoxia in goats, which yielded mixed venous SO2-values between 9 and 4.4% (Crocker and Jones, 2014). Although it cannot be excluded that in the present measurements mixed venous SO2 is somewhat different in normoxia and hypoxia, a deviation of, say, 5% from the assumed venous SO2 would only slightly affect this estimate. We conclude that the reduced O2,max can be satisfactorily explained by the diminished arterial SO2 together with a reasonable value for mixed venous SO2.

Lack of AQP1, but not of Rhag and AQP9, reduces O2,max—possible mechanisms

Table 1 shows that lack of AQP1 reduces O2,max by about 15%, under both normoxia and hypoxia. This constitutes a new phenotype of AQP1-deficient mice, and might be caused by either reduced cardiac output or impaired gas exchange in AQP1-deficient mice. Although in our view there is no clear experimental evidence for a role of AQP1 in O2 transport across membranes, it has been shown by molecular dynamics simulations that AQP1 constitutes a channel for O2 as it does for CO2 (Wang et al., 2007). This fact has been invoked to explain experimental data on the interrelationship between AQP1 and HIF (hypoxia inducible factor) expression (Echevarría et al., 2007).

AQP1 is almost universally present in the capillaries of the body, notably in the lung, the heart and skeletal muscle (Nielsen et al., 1993; Rutkovskiy et al., 2013). It is also present in the red blood cell membrane, where is has been shown to act as a CO2 channel (Endeward et al., 2006a). If AQP1 contributed to O2 exchange in red blood cells, in the lung and in the periphery, it would be conceivable that lack of AQP1 is associated with retarded O2 diffusion in the lung as well as in the periphery. We have shown previously (Al-Samir et al., 2016) that a diffusion problem does not exist in the anesthetized AQP1-deficient mouse under conditions of a low rate of O2 consumption, neither in the lung nor in the periphery. The likelihood that a diffusion problem becomes apparent, however, increases with increasing O2 flow, i.e., O2 consumption, and with decreasing gradients of pO2 across the lung and/or peripheral diffusion barriers. This means, a diffusion limitation is most likely to show up when (a) O2 is maximal and (b) the animal inspires a hypoxic gas mixture. Therefore, we have measured in this study O2 under conditions maximizing the animals' metabolism and under hypoxia.

In view of recent evidence on the morphological and functional properties of the hearts of AQP1-deficient mice (Montiel et al., 2014; Al-Samir et al., 2016), we propose here that the reduced maximal O2 of these mice (Table 1) is due to a reduced maximal cardiac output. In the following, we will discuss the available evidence for impaired gas exchange vs. reduced cardiac output.

Effect of hypoxia on O2,max argues against a diffusion problem

It is characteristic for a limitation by diffusion that the limitation is aggravated when the O2 partial pressure (pO2) gradient that drives the diffusion process is reduced. This happens in the lung as well as in the periphery when the animals are exposed to hypoxia. Our results do not show such a limitation. Under hypoxia, when alveolar pO2 is cut down to roughly one half, the relative reductions of O2,max (Table 1) caused by the lack of AQP1 (15%, 13%) are identical to those observed under normoxia (16%, 16%). This clearly argues against an O2 diffusion problem due to the lack of AQP1. This argument applies to pulmonary as well as peripheral gas exchange.

No limitation of pulmonary O2 exchange apparent from arterial O2 saturation

For pulmonary gas exchange, this conclusion is supported most directly by the data of Table 2. The arterial oxygen saturations obtained by pulse oximetry during conditions of O2,max show no difference between WT and KO animals, both in normoxia and hypoxia. Thus, even under conditions of maximal challenge of O2 diffusion by O2,max in combination with hypoxia, the blood passing though the lung is equally (and fully) equilibrated with alveolar pO2 in KO as well as in WT mice. These data rule out a limiting role of O2 diffusion in the lung. It will be desirable to confirm in the future the normal diffusion properties of the lungs of AQP1-KO mice by directly measuring their diffusion capacities (Fallica et al., 2011). As just discussed, our data also argue against a diffusion limitation of peripheral O2 supply, although direct evidence for this would have required knowledge of venous O2 saturation.

The conclusion regarding the absence of diffusion limitation in the periphery is in line with the distribution of AQP1 in the lung and the periphery. Both in the lung and in skeletal muscle, the exclusive or dominant site of expression is the capillary endothelium. Thus, if lack of AQP1 causes no diffusion problem in the lung, where AQP1 normally is most prominently expressed (Nielsen et al., 1993), it is not likely that it will cause a problem in heart and skeletal muscle.

Comparison of resting vs. maximal O2

As explained above, increasing O2 can—like exposure to hypoxia—uncover a diffusion limitation. Thus, we ask, whether in AQP1-deficient mice a reduction in O2,max is seen (Table 1, 3rd column, lines 1 and 2, and lines 5 and 6) that is not seen in O2, rest (Table 1, 2nd column, lines 1 and 2, and lines 5 and 6). The data given here suggest that a reduction of O2 is present under resting conditions as well as under conditions of maximal O2 consumption. Thus, no diffusion limitation would become apparent here. However, the finding just described is in clear contradiction to own previous observations obtained with the same mice under anesthesia (Al-Samir et al., 2016). The O2-values of WT mice observed in this preceding study were identical to those given in Table 2 for resting conditions. However, there was no difference in O2, rest between WT and KO mice in this study. We believe it likely therefore that the conscious AQP1-deficient mice of the present study exhibit a lower O2, rest than WT animals because of the known reduced spontaneous physical activity of AQP1-deficient mice (Boron, 2010). Accordingly, basal O2 of AQP-KO animals is likely to be equal to that of WT animals, but O2,max is reduced in KO compared to WT animals. We consider it likely, nevertheless, that this does not reflect a diffusion limitation but is caused by the properties of the hearts of WT and KO animals, as explained below.

Role of red cell membranes as barriers to O2 diffusion

If AQP1, which is present in mouse as well as in human red cells, would contribute to O2 transfer across the membrane, the presence or absence of AQP1 could make a difference in pulmonary as well as peripheral gas exchange. As discussed above, the present results suggest that this is not the case. While no measurements of the O2 permeability of mouse or human red cells are available, such measurements have been reported for CO2. Under the assumption that AQP1 is a channel for O2 as it is for CO2 (Wang et al., 2007), the permeabilities measured for CO2 might be similar for O2. While AQP1 makes a major difference for the CO2 permeability of human red cells (Endeward et al., 2006a,b) as does RhAG (Endeward et al., 2008), this is not so clear for mouse red cells. Yang et al. (2000) and Ripoche et al. (2006) found no difference in CO2 permeability of the red cells of mice either lacking AQP1 or Rhag. Own unpublished measurements support this (T. Meine, S. Al-Samir, V. Endeward, G. Gros). Thus, it seems possible that the red cell membranes of the knockout mice have identical properties to those of WT, and thus a differential contribution of KO and WT red cells to peripheral and pulmonary gas exchange would indeed not be expected.

Can the heart of the AQP1-deficient mouse be responsible for reduced O2,max?

If we reject an interpretation of the present data in terms of a diffusion problem, we are left with the known reduced left ventricular weight and wall thickness of the KO animals (Montiel et al., 2014; Al-Samir et al., 2016). This must be expected to be associated with a reduced maximal cardiac output and thus reduced O2,max. Since in the preceding study we have shown that cardiac function of AQP1-deficient animals under resting conditions is entirely normal including stroke volume and heart rate, this interpretation nicely explains why (normoxic) resting O2 under anesthesia is not reduced (cf. Al-Samir et al., 2016), but (normoxic) O2,max is impaired (Table 1, 3rd column), as just discussed. It likewise explains satisfactorily why O2,max is reduced to the same extent in normoxia and hypoxia, as discussed above.

We conclude that several lines of evidence argue against the existence of an O2 diffusion problem in mice lacking AQP1. This does not rule out that AQP1 acts as a pore for O2, but can be due to a rather high background permeability of biological membranes without AQP1. This would be in agreement with the very high O2 permeabilities observed by Subczynski et al. (1989, 1992) in artificial phospholipid and in biological membranes. If the basal O2 permeability of these membranes is so high, O2 transfer across AQP1 would not noticeably increase O2 permeation across the membrane. This is quite in contrast to what we and others have shown for the case of CO2 (Endeward et al., 2006a, 2008; Musa-Aziz et al., 2009; Itel et al., 2012), where AQP1 generates a significant increase in CO2 permeability of membranes containing a major fraction of cholesterol. Instead, AQP1 deficiency obviously limits maximal oxygen consumption by being associated with a reduced cardiac muscle mass and wall thickness, which must be postulated to go along with a reduced maximal cardiac output.

Author contributions

Concept of study: SA, SS, GG, VE. Experiments: SA, FS, VE. Interpretation of data: SA, SS, GG, VE. Contribution of materials and animals: DG, JPC, SN. Writing the draft of the paper: GG. Contribution to final version of the paper: SA, DG, JPC, SN, FS, SS, GG, VE.

Funding

We thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for funding this work with grant No. EN 908/2-1.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sabine Klebba-Färber for excellent technical assistence.

References

- Al-Samir S., Wang Y., Meißner J. D., Gros G., Endeward V. (2016). Cardiac morphology and function, and blood gas transport in aquaporin-1 knockout mice. Front. Physiol. 7:181. 10.3389/fphys.2016.00181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boron W. F. (2010). Sharpey-Schafer lecture: gas channels. Exp. Physiol. 95, 1107–2230. 10.1113/expphysiol.2010.055244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell M. A. (1984). Maximum oxygen consumption during exercise and cold exposure in deer mice, Peromyscus maniculatus. Respir. Physiol. 55, 367–377. 10.1016/0034-5687(84)90058-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker G. H., Jones J. H. (2014). Hypoxia and CO alter O2 extraction but not peripheral diffusing capacity during maximal aerobic exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 114, 837–845. 10.1007/s00421-013-2799-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai K. H., Sato R., Schauble E., Barsh G. S., Kobilka B. K., Bernstein D. (1997). Cardiovascular indexes in the mouse at rest and with exercise: new tools to study models of cardiac disease. Am. J. Physiol. 272, H1053–H1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echevarría M., Muñoz-Cabello A. M., Sánchez-Silva R., Toledo-Aral J. J., López-Barneo J. (2007). Development of cytosolic hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factor stabilization are facilitated by aquaporin-1 expression. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 30207–30215. 10.1074/jbc.M702639200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endeward V., Cartron J. P., Ripoche P., Gros G. (2006b). Red cell membrane CO2 permeability in normal human blood and in blood deficient in various blood groups, and effect of DIDS. Transfus. Clin. Biol. 13, 123–127. 10.1016/j.tracli.2006.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endeward V., Cartron J. P., Ripoche P., Gros G. (2008). RhAG protein of the Rhesus complex is a CO2 channel in the human red cell membrane. FASEB J. 22, 64–73. 10.1096/fj.07-9097com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endeward V., Musa-Aziz R., Cooper G. J., Chen L. M., Pelletier M. F., Virkki L. V., et al. (2006a). Evidence that aquaporin 1 is a major pathway for CO2 transport across the human erythrocyte membrane. FASEB J. 20, 1974–1981. 10.1096/fj.04-3300com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallica J., Das S., Horton M., Mitzner W. (2011). Application of carbon monoxide diffusing capacity in the mouse lung. J. Appl. Physiol. 110, 1455–1459. 10.1152/japplphysiol.01347.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer R. R., Musa-Aziz R., Qin X., Boron W. F. (2013). Relative CO2/NH3 selectivities of mammalian aquaporins 0-9. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 304, C985–C994. 10.1152/ajpcell.00033.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens D., Trinh-Trang-Tan M. M., Debbia M., Ripoche P., Vilela-Lamego C., Louache F., et al. (2010). Generation and characterisation of Rhd and Rhag null mice. Br. J. Haematol. 148, 161–172. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07928.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoevenaars F. P., Bekkenkamp-Grovenstein M., Janssen R. J., Heil S. G., Bunschoten A., Hoek-van den Hil E. F., et al. (2014). Thermoneutrality results in prominent diet-induced body weight differences in C57BL/6J mice, not paralleled by diet-induced metabolic differences. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 58, 799–807. 10.1002/mnfr.201300285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoit B. D., Walsh R. A. (2002). Cardiovascular Physiology in the Genetically Engineered Mouse, 2nd Edn. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Hub J. S., de Groot B. L. (2006). Does CO2 permeate through aquaporin-1? Biophys. J. 91, 842–848. 10.1529/biophysj.106.081406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hub J. S., Winkler F. K., Merrick M., de Groot B. L. (2010). Potentials of mean force and permeabilities for carbon dioxide, ammonia, and water flux across a Rhesus protein channel and lipid membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 13251–13263. 10.1021/ja102133x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itel F., Al-Samir S., Öberg F., Chami M., Kumar M., Supuran C. T., et al. (2012). CO2 permeability of cell membranes is regulated by membrane cholesterol and protein gas channels. FASEB J. 26, 5182–5191. 10.1096/fj.12-209916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer K., van Acker S. A., Voss H.-P., Grimbergen J. A., van der Vijgh W. J., Bast A. (1993). Use of telemetry to record electrocardiogram and heart rate in freely moving mice. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 30, 209–215 10.1016/1056-8719(93)90019-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner A. J. (1978). The scaling of maximal oxygen consumption and pulmonary dimensions in small mammals. Respir. Physiol. 34, 29–44. 10.1016/0034-5687(78)90047-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T., Yang B., Gillespie A., Carlson E. J., Epstein C. J., Verkman A. S. (1998). Severely impaired urinary concentrating ability in transgenic mice lacking aquaporin-1 water channels. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 4296–4299. 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montiel V., Leon Gomez E., Bouzin C., Esfahani H., Romero Perez M., Lobysheva I., et al. (2014). Genetic deletion of aquaporin-1 results in microcardia and low blood pressure in mouse with intact nitric oxide-dependent relaxation, but enhanced prostanoids-dependent relaxation. Pflügers Arch. 466, 237–251. 10.1007/s00424-013-1325-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musa-Aziz R., Chen L. M., Pelletier M. F., Boron W. F. (2009). Relative CO2/NH3 selectivities of AQP1, AQP4, AQP5, AmtB, and RhAG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 5406–5411. 10.1073/pnas.0813231106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen S., Smith B. L., Christensen E. I., Agre P. (1993). Distribution of the aquaporin CHIP in secretory and resorptive epithelia and capillary endothelia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 7275–7279. 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripoche P., Goossens D., Devuyst O., Gane P., Colin Y., Verkman A. S., et al. (2006). Role of RhAG and AQP1 in NH3 and CO2 gas transport in red cell ghosts: a stopped-flow analysis. Transfus. Clin. Biol. 13, 117–122. 10.1016/j.tracli.2006.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojek A. M., Skowronski M. T., Füchtbauer E. M., Füchtbauer A. C., Fenton R. A., Agre P., et al. (2007). Defective glycerol metabolism in aquaporin 9 (AQP9) knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 3609–3614. 10.1073/pnas.0610894104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenmann M., Morrison P. (1974). Maximum oxygen consumption and heat loss facilitation in small homeotherms by He-O2. Am. J. Physiol. 226, 490–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkovskiy A., Valen G., Vaage J. (2013). Cardiac aquaporins. Basic Res. Cardiol. 108, 393. 10.1007/s00395-013-0393-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler B., Arras M., Keller S., Rettich A., Lundby C., Vogel J., et al. (2010). Optimal hematocrit for maximal exercise performance in acute and chronic erythropoietin-treated mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 419–423. 10.1073/pnas.0912924107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segrem N. P., Hart J. S. (1967). Oxygen supply and performance in Peromyscus. Comparison of exercise with cold exposure. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 45, 543–549. 10.1139/y67-063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subczynski W. K., Hopwood L. E., Hyde J. S. (1992). Is the mammalian cell plasma membrane a barrier to oxygen transport? J. Gen. Physiol. 100, 69–87. 10.1085/jgp.100.1.69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subczynski W. K., Hyde J. S., Kusumi A. (1989). Oxygen permeability of phosphatidylcholine–cholesterol membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 4474–4478. 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Engelhardt W., Breves G., Diener M., Gäbel G. (2015). Physiologie der Haustiere. Stuttgart: Enke-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Cohen J., Boron W. F., Schulten K., Tajkhorshid E. (2007). Exploring gas permeability of cellular membranes and membrane channels with molecular dynamics. J. Struct. Biol. 157, 534–544. 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Tajkhorshid E. (2010). Nitric oxide conduction by the brain aquaporin AQP4. Proteins 78, 661–670. 10.1002/prot.22595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B., Fukuda N., van Hoek A., Matthay M. A., Ma T., Verkman A. S. (2000). Carbon dioxide permeability of aquaporin-1 measured in erythrocytes and lung of aquaporin-1 null mice and in reconstituted proteoliposomes. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 2686–2692. 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]