Abstract

A3C60 molecular superconductors share a common electronic phase diagram with unconventional high-temperature superconductors such as the cuprates: superconductivity emerges from an antiferromagnetic strongly correlated Mott-insulating state upon tuning a parameter such as pressure (bandwidth control) accompanied by a dome-shaped dependence of the critical temperature, Tc. However, unlike atom-based superconductors, the parent state from which superconductivity emerges solely by changing an electronic parameter—the overlap between the outer wave functions of the constituent molecules—is controlled by the C603− molecular electronic structure via the on-molecule Jahn–Teller effect influence of molecular geometry and spin state. Destruction of the parent Mott–Jahn–Teller state through chemical or physical pressurization yields an unconventional Jahn–Teller metal, where quasi-localized and itinerant electron behaviours coexist. Localized features gradually disappear with lattice contraction and conventional Fermi liquid behaviour is recovered. The nature of the underlying (correlated versus weak-coupling Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer theory) s-wave superconducting states mirrors the unconventional/conventional metal dichotomy: the highest superconducting critical temperature occurs at the crossover between Jahn–Teller and Fermi liquid metal when the Jahn–Teller distortion melts.

This article is part of the themed issue ‘Fullerenes: past, present and future, celebrating the 30th anniversary of Buckminster Fullerene’.

Keywords: fullerenes, superconductivity, electron correlation, Mott insulator, antiferromagnetism, Jahn–Teller effect

1. Introduction

Notwithstanding its stability, which led to its original detection [1], C60 readily participates in many chemical reactions, primarily acting as a soft electrophile (electron-deficient alkene) or a ‘radical sponge’. Its high electron affinity and the weak intermolecular van der Waals forces between the molecules in the cubic-structured crystal [2] also make it an excellent potential host for solid-state reductive intercalation chemistry. This has important consequences for the properties of the resulting materials. Although solid C60 is, unlike semimetallic graphite, a very poor conductor, with a bandgap of 1.9 eV, reaction with good electron donors, like the alkali metals, can lead to an increase in electrical conductivity of several orders of magnitude [3]. This has generated considerable interest and resulted in the subsequent isolation of a wealth of intercalated alkali fulleride salts with stoichiometries AxC60, where x can be as low as 1 (e.g. RbC60) or as high as 12 (e.g. Li12C60) depending on the size of the dopant ion; the broad compositional range also reflects the ease of reduction of C60, especially to oxidation states ranging from −1 to −6. Some of the members of the alkali fulleride family with stoichiometry A3C60 (A = alkali metal) were found to become superconducting [4,5], with their critical temperature Tc being sensitively affected by the nature and size of the dopants [6]. At ambient pressure, their Tc reaches values as high as 33 K (for the RbCs2C60 composition [7]).

The superconducting A3C60 compositions adopt either merohedrally disordered face-centred cubic (fcc) structures in fullerides containing large alkali ions (K, Rb, Cs) [8] or orientationally ordered primitive cubic structures in those containing the smaller Na+ ion [9]. In both cases, the three cations occupy the available octahedral and tetrahedral interstitial sites in the cubic close-packed structure of solid C60 (figure 1a,b). Charge transfer between the alkali metals and the C60 molecules is essentially complete, and the conduction band of C60, which arises from its lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of t1u symmetry, is half-filled (figure 2a). In both A3C60 structural types, there are octahedral (one per C60 unit with a radius of 2.06 Å) and tetrahedral (two per C60 unit with a radius of 1.12 Å) interstices, which are occupied by the alkali cations. The C60–C60 distance is directly controlled principally by the ionic size of the metal ion residing in the tetrahedral holes. As the dopant size increases, the interfullerene separation and lattice constant increase, and Tc of the fcc A3C60 fullerides is found to increase monotonically (figure 2b) [6]. Notably, the rate of change of Tc with interfullerene spacing is much steeper in the primitive cubic family (figure 2b) [9,10]. The experimental observations appear consistent with a conventional electron–phonon coupling model where pair-binding is dominated by intramolecular properties and Tc is modulated by the density of states at the Fermi level, N(εF) [6,11]. As the interfullerene spacing increases, the overlap between the molecules decreases; this leads to a reduced bandwidth, and, for a fixed band filling, to an increased N(εF). This in turn leads to an increased Tc through a (Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer) BCS-type relationship:

]. Here,

]. Here,  is the average intramolecular phonon energy and v is the electron–phonon coupling strength. The observed Tc and the Tc(a0) dependence could be understood within a BCS-like phenomenology, in terms of (i) a high average phonon frequency ωph (of comparable magnitude to the Fermi energy) resulting from the light carbon mass and the large force constants associated with the intramolecular modes, (ii) a moderately large electron–phonon coupling constant v with contributions from both radial and tangential C60 vibrational modes [12] and (iii) a high N(εF) arising from the weak intermolecular interactions and narrow t1u-derived conduction bandwidth (figure 2a).

is the average intramolecular phonon energy and v is the electron–phonon coupling strength. The observed Tc and the Tc(a0) dependence could be understood within a BCS-like phenomenology, in terms of (i) a high average phonon frequency ωph (of comparable magnitude to the Fermi energy) resulting from the light carbon mass and the large force constants associated with the intramolecular modes, (ii) a moderately large electron–phonon coupling constant v with contributions from both radial and tangential C60 vibrational modes [12] and (iii) a high N(εF) arising from the weak intermolecular interactions and narrow t1u-derived conduction bandwidth (figure 2a).

Figure 1.

Crystalstructures of superconducting A3C60 (A = alkali metal) compositions. (a) Face-centred cubic (fcc) unit cell (space group  ). Two orientations related by 44°23′ rotation about the [111] crystal axis exist in a disordered manner—only one of these is shown at each site for clarity. The A+ ions are depicted as red and green spheres to signify symmetry-inequivalent positions in the unit cell—octahedral and tetrahedral sites, respectively. (b) Primitive cubic unit cell (space group

). Two orientations related by 44°23′ rotation about the [111] crystal axis exist in a disordered manner—only one of these is shown at each site for clarity. The A+ ions are depicted as red and green spheres to signify symmetry-inequivalent positions in the unit cell—octahedral and tetrahedral sites, respectively. (b) Primitive cubic unit cell (space group  ). The C603− anions are orientationally ordered and their orientations are optimized for an anticlockwise rotation about [111] of approximately 98°. Two crystallographically distinct A+ sites are present as in the fcc analogues. (c) A15 unit cell (space group

). The C603− anions are orientationally ordered and their orientations are optimized for an anticlockwise rotation about [111] of approximately 98°. Two crystallographically distinct A+ sites are present as in the fcc analogues. (c) A15 unit cell (space group  ) based on body-centred cubic (bcc) anion packing. One unique orientation of the C603− anions and a single crystallographically distinct A+ (tetrahedral) site are present.

) based on body-centred cubic (bcc) anion packing. One unique orientation of the C603− anions and a single crystallographically distinct A+ (tetrahedral) site are present.

Figure 2.

(a) Molecular orbital energy scheme for the C603− anion and the corresponding valence and conduction bands for solid A3C60. (b) Variation of the superconducting transition temperature Tc with cubic lattice parameter a0 for various compositions of fcc A3C60 and primitive cubic Na2A′C60 (A′=Rb, Cs). The dotted line is the Tc−a0 relationship expected from BCS theory using N(εF) values obtained by LDA calculations, while the straight line is a guide to the eye. (Online version in colour.)

Although such a BCS-type approach can nicely rationalize the observed Tc of A3C60 alkali fullerides, there are certain features of their electronic structures that do not fit into the phenomenology developed and necessitate consideration of alternative pair-binding scenarios such as those proposed by purely electronic models [13]. These were related to the relative magnitude of the t1u-derived conduction bandwidth W and the on-site Coulomb repulsion U. In common with strongly correlated electron systems like high-Tc cuprate [14], heavy-fermion [15] and organic [16] superconductors, the on-site Coulomb repulsion, U, in A3C60 fullerides is comparable to or greater than the t1u bandwidth, W. Estimates of U for the C60 molecule are of the order of 3 eV. This value is significantly reduced in the solid to approximately 1 eV [17]. As typical values of W for all cubic A3C60, which also retain the LUMO triple orbital degeneracy, are of the order of 0.5 eV, the ratio (U/W) is much larger than 1. Therefore, it should be expected that the t1u band splits into two—a lower Hubbard sub-band that is fully occupied and an upper Hubbard sub-band that is empty—and, as a result, a Mott–Hubbard insulator should be observed experimentally. For this reason, it was suggested that the metallic and superconducting behaviour in A3C60 arises through the effect of non-stoichiometry, namely the true composition of these fullerides is A3−δC60 [17]. However, when the triple orbital degeneracy of the LUMO states and the geometric frustration associated with the fcc packing topology are taken into account, the boundary of the metal–insulator transition shifts to a critical value of (U/W)c∼2.3 [18]; such considerations naturally allow the highly correlated nature of the metallic and superconducting states of stoichiometric fcc-structured A3C60 to emerge [19]. Many early accounts exist of the electronic and superconducting properties of intercalated alkali fullerides as a function of interfullerene separation, orientational order/disorder, valence state, band filling, orbital degeneracy, low-symmetry distortions and metal–C60 interactions [20–30].

2. Expanded fullerides: small-molecule co-intercalation

An immediate issue arising from the correlation between Tc and interfullerene separation, depicted in figure 2b, is that, if one were to be successful in synthesizing new fulleride phases with even larger lattice parameters, would these be superconducting with increased Tc or would the expected band narrowing at hyperexpansion lead to electron localization and a transition to a Mott-insulating state? While the on-site interelectronic repulsion, U, is a molecular quantity and should vary little across the A3C60 series, the width of the t1u conduction band, W, depends sensitively on the interfullerene separation, and the ratio (U/W) increases with increasing lattice constant. As a result, for large enough interball separations, (U/W) may exceed the critical value of 2.3 predicted by theory [18] for the transition to an insulating state. This idea was addressed experimentally by using as structural spacers alkali ions solvated with neutral molecules, such as ammonia and methylamine (figure 3a). The NH3 or CH3NH2 molecules coordinate to the alkali metal ions, leading to large effective radii for the resulting species, which reside in the octahedral interstitial sites of the fullerene structure, while the extent of charge transfer is maintained. This synthetic strategy led to the isolation not of superconducting fullerides but rather of insulating compositions such as (NH3)K3C60 [31–33] and (CH3NH2)K3C60 [34] with interfullerene separations (10.57 and 10.74 Å, respectively) significantly exceeding that of the 33 K RbCs2C60 superconductor (SC; 10.29 Å; figure 3b). The key issue here is that lattice expansion is anisotropic and is consequently accompanied by a reduction in crystal symmetry from face-centred cubic to face-centred orthorhombic. This lifts the degeneracy of the t1u orbitals and suppresses the critical value of the (U/W) ratio for the transition to the insulating state to occur [18]. As the degeneracy of the t1u orbitals is lifted and the effect of frustration is also removed, (U/W)c decreases from approximately 2.3 to approximately 1 and the electronic properties of, for example, (NH3)K3C60 and (CH3NH2)K3C60 are drastically different from those of their cubic metallic and superconducting analogues with comparable interfullerene separations. This is aided by the increased interfullerene separation, substantially larger than the value of 10.05 Åfound in parent K3C60, which reduces the bandwidth W and increases further (U/W). In accord with this, the electronic ground states of these expanded but symmetry-lowered fullerides were authenticated as those of S=1/2 long-range-ordered antiferromagnetic (AFM) insulators bordering the metallic and superconducting phases (figure 3b) [35–37]. This provided for the first time the hint of an intriguing commonality with the phenomenology in organic and high-Tc superconductors [14,16], namely the proximity to a magnetic Mott-insulating state whose suppression leads to the emergence of the superconductivity.

Figure 3.

(a) K+–NH3 and K+–NH2–CH3 units occupying the octahedral sites of expanded orthorhombic fullerides with stoichiometries (NH3)A3C60 and (CH3NH2)A3C60 (A = alkali metal), respectively. (b) Electronic phase diagram of fullerides including the superconducting Tc values for fcc-structured A3C60 superconductors (open circles) and the Néel TN values for the fco-structured antiferromagnets, (NH3)A3C60 (open/solid squares) and (CH3NH2)K3C60 (triangle). The LUMO schemes are illustrated for the cubic metallic/superconducting (retention of orbital degeneracy) and the orthorhombic AFM insulating (degeneracy-lifting, low-spin magnetic state) compositions. The shaded area denotes the metal–antiferromagnetic insulator boundary. (Online version in colour.)

3. Expanded fullerides: the superconductivity dome and electron correlations

Despite the insight provided by the expanded ammoniated/aminated alkali fullerides through the suppression of the metallic state and the appearance of long-range magnetic order in the insulating state, there has been no definitive experimental evidence for a non-BCS origin for superconductivity in fullerides, where correlation would play a role. Therefore, what has been missing since the early days of fulleride superconductivity research are model systems in which the metal–insulator transition could be traversed in a purely electronic manner without the complications of structural transitions, while at the same time maintaining the site symmetry required for orbital degeneracy to survive in all the potentially competing electronic ground states (figure 3b). Such materials finally became available in the form of the two polymorphs (A15 and fcc) of the most expanded binary cubic fulleride, Cs3C60, and the ternary solid-solution fcc compositions, RbxCs3−xC60 (0≤x≤3) (figure 1a,c) [38].

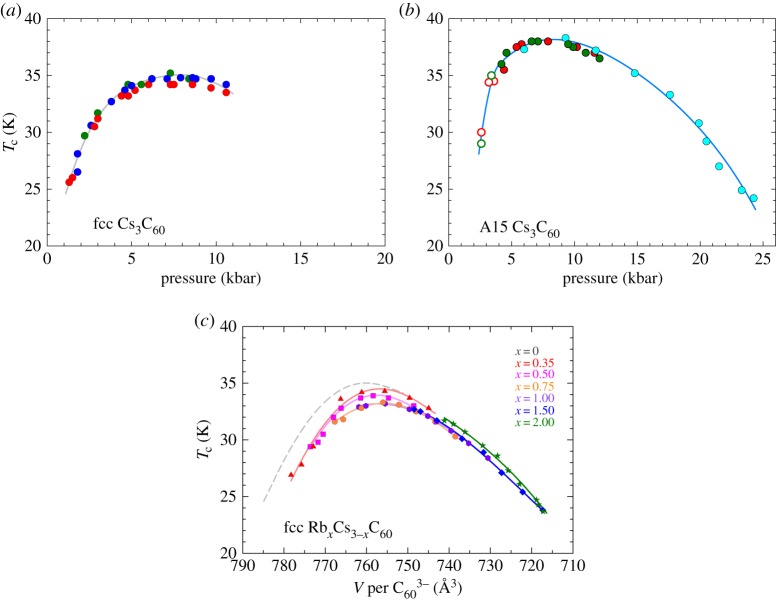

Both Cs3C60 polymorphs are not superconductors at ambient pressure but superconductivity can be switched on without crystal structure change [39,40] by the application of moderate external pressures [39–41]. As superconductivity emerges upon pressurization, Tc rapidly increases and reaches a maximum (35 K in fcc-structured Cs3C60, 38 K in A15-structured Cs3C60—this is the highest Tc observed in a bulk molecular material) at approximately 7 kbar before decreasing upon further increase in pressure (figure 4a,b). The ternary compositions, RbxCs3−xC60 (0≤x≤3), mimic the electronic response of the two Cs3C60 polymorphs under pressure; gradual substitution of the smaller Rb+ for the Cs+ cation in fcc Cs3C60 is equivalent to applying chemical pressure to the parent material and similarly leads to the emergence of superconductivity at ambient pressure with increasing Rb content, x. The rapidly increasing Tc reaches a maximum value before its chemical pressure coefficient turns into negative and Tc begins to decrease (figure 4c) [43]. These results transformed the entire field of fullerene superconductivity, as they established the existence of a key commonality with other unconventional superconductors—the presence of a conduction bandwidth-controlled superconductivity dome in their electronic phase diagram. Density functional theory calculations in the absence of electron correlations find a smooth evolution of the density of states at the Fermi level, N(εF), and the conduction bandwidth, W, throughout the entire region of the phase diagram, including interfullerene separations where experimentally Tc changes sign [44]. This suggests that superconducting pairing in fullerides is more complex than simply originating from BCS-like electron–phonon coupling and necessitates the presence of an additional parameter.

Figure 4.

Superconducting transition temperature, Tc, as a function of pressure for (a) fcc- and (b) A15-structured Cs3C60 [40,42]. (c) Tc as a function of volume occupied per fulleride anion, V , at low temperature for selected fcc-structured RbxCs3−xC60 (0≤x≤2) compositions [43].

Evidence for the identity of this extra ingredient came from the observation that both parent non-superconducting Cs3C60 polymorphs are AFM (S=1/2) Mott insulators—the hallmark of strong electron correlations. The Néel temperature TN of A15-structured bipartite Cs3C60 is 46 K [41,42], while that of geometrically frustrated fcc is significantly suppressed to 2.2 K [40,45]. Therefore, the AFM insulator to SC transition is purely electronically driven without any crystal structure change by (physical or chemical) pressure. It is of first order as evidenced by the coexistence of the two competing electronic states over a finite pressure range [42] and antiferromagnetism is transformed into superconductivity solely by changing an electronic parameter: the extent of overlap between the outer wave functions of the constituent anions (figure 5). Thus, unlike in the less expanded systems with smaller alkali metals, the electron correlation effects represented by U dominate despite the retained orbital degeneracy in the expanded cubic fulleride phases, providing direct evidence that correlation directly competes with superconductivity in cubic A3C60 materials. Therefore, the fullerides should be considered as correlated electron systems controlled by Mott–Hubbard physics in the region corresponding to the highest Tc.

Figure 5.

Electronic phase diagram of A15 Cs3C60 showing the evolution of the Néel temperature TN (squares) and Tc (circles) as a function of volume occupied per fulleride anion, V , at low temperature [42]. AFI, antiferromagnetic insulating state; SC, superconducting state.

Theoretical models of the fullerides beyond conventional BCS theory, which treated electron correlation effects and conventional coupling of electrons to phonons by Jahn–Teller-active intramolecular C60 vibrations on an equal footing, predicted correlation enhancement of superconductivity near the metal–insulator transition and provided significant steps forward in understanding the parent insulating and the correlated metallic and high-Tc superconducting states [19,46–50]. Indirect evidence of the relevance of the Jahn–Teller effect in Mott-insulating Cs3C60 is provided by the observation of a low-spin S=1/2 ground state [40,42,43] despite the retention of cubic symmetry, which should have led to a high-spin S=3/2 state for the C603− anion (figure 6). More directly, infrared spectroscopy unambiguously identified the existence of subtle changes in the shape of the C603− ion due to dynamic Jahn–Teller distortions in both insulating fcc and A15 Cs3C60 polymorphs [51]. These results were corroborated by low-temperature magic-angle-spinning 13C and 133Cs NMR experiments [52] on the fcc Cs3C60 polymorph. The interconversion rate, kJT, between different Jahn–Teller conformers was shown to lie in the range 105<kJT<1011 s−1. These experimental findings can be rationalized by considering the competition between the Jahn–Teller interaction JJT, caused by coupling of the electrons to symmetry-lowering molecular vibrations, and the Coulomb exchange energy JH, which favours highest total spin and orbital angular momentum (Hund’s rule) [47]. The condition JJT>JH leads to a physical regime of ‘inverted Hund’s rule coupling’ and is consistent with the occurrence of a low-spin state. However, even though the Jahn–Teller effect is strong enough to overcome Hund’s rule to enforce a low-spin state, it is not strong enough to break the global cubic symmetry.

Figure 6.

Molecular orbitals of C603− for (a) undistorted Ih symmetry with an unsplit triply degenerate t1u LUMO and (b) Jahn–Teller-distorted D2h symmetry with threefold splitting (b1u, b2u and b3u) of the LUMO [51]. (Online version in colour.)

According to this interpretation, both Cs3C60 polymorphs can be classified as magnetic Mott–Jahn–Teller (MJT) insulators, with the on-molecule dynamic distortion creating the S=1/2 ground state, which produces the magnetism from which the superconductivity emerges. Contraction of the MJT insulator through (chemical or physical) pressurization yields a metallic state which becomes superconducting on cooling. Infrared spectroscopy has revealed that the insulator-to-metal crossover is not immediately accompanied by the suppression of the molecular Jahn–Teller distortions [43]. The metallic state that emerges following the destruction of the Mott insulator is unconventional—correlations sufficiently slow carrier hopping and the intramolecular Jahn–Teller (JT) effect coexists with metallicity. This inhomogeneous Jahn–Teller metallic state of matter shows both molecular (dynamically JT-distorted C603− ions) and free-carrier (electronic continuum) features. The JT metal exhibits a strongly enhanced spin susceptibility relative to that of a conventional Fermi liquid, characteristic of the importance of strong electron correlations. As the fulleride lattice contracts further, there is a crossover from the JT metal to a conventional Fermi liquid state upon moving from the Mott boundary towards the under-expanded regime, with the molecular distortion arising from the JT effect disappearing and the electron mean free path extending to more than a few intermolecular distances [43]. Remarkably, the JT to conventional metal crossover occurs exactly where the maximum Tc is found for optimally expanded fullerides (figure 7).

Figure 7.

Globalelectronic phase diagram of fcc-structured RbxCs3−xC60 showing the evolution of Tc (ambient P, solid triangles; high P, unfilled triangles) and the MJT insulator-to-JT metal crossover temperature, T′ (synchrotron X-ray diffraction, squares; χ(T), stars; 13C, 87Rb and 133Cs NMR spectroscopy, hexagons with white, colour and black edges, respectively; IR spectroscopy, diamonds), as a function of V per C60 [43]. Within the metallic (superconducting) regime, gradient shading from orange to green (purple) schematically illustrates the JT metal to conventional metal (unconventional to weak-coupling BCS conventional SC) crossover.

Therefore, the crossover of the electronic states across the bandwidth-controlled phase diagram from an MJT insulator to a JT metal and then to a Fermi liquid state directly affects the superconducting states that lie underneath. NMR spectroscopy reveals that the spin–lattice relaxation rate, 1/T1, follows an activated behaviour, with a single isotropic BCS-like (s-wave) superconducting gap, Δ0, opening below Tc across the entire electronic phase diagram from over- through optimally to under-expanded (both chemically and physically pressurized) A3C60 fullerides [43,53]. The normalized gap ratios (2Δ0/kTc) for under-expanded conventional metallic fullerides far away from the Mott-insulator boundary take values characteristic of weak-coupling BCS superconductors (approx. 3.52). However, as the lattice expansion reaches optimal values and beyond, (2Δ0/kTc) begins to increase monotonically, approaching and then exceeding a value of 5 [43,53,54] for superconductors emerging from JT metals upon cooling. Therefore, the superconducting gap does not correlate with Tc in the over-expanded regime, where molecular features play a dominant role in producing the unconventional superconductivity. In contrast to the dome-shaped dependence of Tc on packing density, V , the gap increases monotonically with interfullerene separation (figure 8). Notably, the maximum Tc occurs at the crossover between the two types of gap behaviour. Such a picture contrasts sharply with the situation established in the (single-band single-gap d-wave) cuprate and (multi-band multi-gap s-wave) iron pnictide superconductors. In both the latter families, the gap magnitudes generally first increase with doping in the underdoped regime, varying in a similar manner to Tc, but then they soon reach a maximum and remain at the same size for larger doping levels [55,56].

Figure 8.

Contrasting dependence of the normalized superconducting gap, 2Δ0/kBTc, and of the superconducting transition temperature, Tc, on fulleride packing density, V [38,43,53]. (Online version in colour.)

In principle, the large gap ratio values close to the Mott-insulator boundary could be obtained for strong electron–phonon coupling, but this would require optical or intermolecular phonons (ωph∼100 cm−1) [57] to take part in the superconducting pairing mechanism. The weak-coupling BCS value of 3.52 found for under-expanded systems can only be obtained by the involvement of the intramolecular phonons (ωph∼1000–1500 cm−1) in the pairing interaction. The volume dependence of (2Δ0/kTc) would thus then require that phonon modes in distinctly different spectral regions are active in different parts of the electronic phase diagram. This is unlikely, as the intramolecular phonon modes are always present and cannot be active only in one part of the phase diagram. Therefore, these arguments rule out the conventional BCS-like explanation of superconductivity in A3C60 fullerides, despite the retention of s-wave symmetry over the entire phase diagram, and implicate as the additional parameter in the superconducting mechanism the importance of correlations relative to the electronic bandwidth.

4. Conclusion

In fulleride superconductors, because of the intrinsically high crystal symmetry and the initial t1u orbital degeneracy at εF, we can directly see via the dynamic JT distortion the manifestation of the electrons’ molecular origin at quantifiable intermolecular separations and link this to the understanding of the collective transport and superconducting pairing properties. In this way, the cause of the anomalous normal state properties can be precisely identified as the heterogeneous persistence of the molecular JT effect into the metallic state via the combined action of electron–electron and electron–phonon interactions, allowing us to link the onset of unconventional normal and superconducting state behaviour with the highest Tc currently achievable in these systems. The superconductivity dome arises from the two distinct branches of the Tc(V) relationship. From the MJT insulator side, Tc increases from the metal–insulator boundary as V decreases and the molecular character of the states at εF reduces. From the metallic side, the extended features in the electronic structure give a different, conventional N(εF) dependence of Tc, which declines as V decreases. The Tc maximum at optimal expansion then corresponds to the optimal balance of extended and molecular characteristics at εF and thus occurs in the crossover region between the two behaviours. These molecular characteristics are specifically the on-molecule JT coupling controlling t1u degeneracy and thus the role of correlation, the resulting orbital ordering and inter-anion magnetic exchange, the C603− anion spin state and the electron–phonon coupling to JT-active modes.

The prevailing feature of the theoretical literature on correlated fulleride superconductivity [19,46–50] has been the necessity to implicate the (dynamic) JT effect in order to account for the robust experimental finding of a low-spin electronic ground state in the Mott-insulating precursor state of the superconductors. This rests on the assumption that electron–electron interactions per se always favour the high-spin electronic configuration. It is therefore intriguing that recent theoretical calculations [58] of the t−J model of short-range repulsions on a C60 molecule show that Hund’s first rule is violated without the necessity of electron–phonon interactions (dynamic Jahn–Teller effect). Moreover, for an average of three electrons per molecule (C603−), an effective attraction (pair-binding) occurs, making it favourable to place four electrons on one molecule (C604−) and two on a second (C602−) rather than putting three on each. A dominantly electronic mechanism of superconductivity in the fullerides is therefore possible and not precluded by the currently available experimental findings and remains an intriguing area of investigation for future work in this field.

Acknowledgements

We thank our co-workers M. T. McDonald, M. D. Tzirakis, R. H. Zadik, R. H. Colman and G. Klupp (Durham University, UK) for their contributions to this work and gratefully acknowledge a long-standing collaboration with the research groups of Prof. M. J. Rosseinsky (University of Liverpool, UK), Prof. D. Arčon (Jozef Stefan Institute, Ljubljana), Prof. Y. Iwasa (University of Tokyo) and Prof. K. Kamarás (Wigner Research Centre for Physics, Budapest).

Authors' contributions

The authors contributed equally to the research reported in this paper.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was sponsored by the ‘World Premier International (WPI) Research Center Initiative for Atoms, Molecules and Materials’, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. We thank SPring-8, the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, and RIKEN for access to synchrotron X-ray facilities and ISIS for access to muon facilities.

References

- 1.Kroto HW, Heath JR, O’Brien SC, Curl RF, Smalley RE. 1985. C60: Buckminsterfullerene. Nature 318, 162–163. ( 10.1038/318162a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.David WIF, Ibberson RM, Matthewman JC, Prassides K, Dennis TJS, Hare JP, Kroto HW, Taylor R, Walton DRM. 1991. Crystal structure and bonding of ordered C60. Nature 353, 147–149. ( 10.1038/353147a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haddon RC. et al. 1991. Conducting films of C60 and C70 by alkali-metal doping. Nature 350, 320–322. ( 10.1038/350320a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hebard AF, Rosseinsky MJ, Haddon RC, Murphy DW, Glarum SH, Palstra TTM, Ramirez AP, Kortan AR. 1991. Superconductivity at 18 K in potassium-doped C60. Nature 350, 600–601. ( 10.1038/350600a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holczer K, Klein O, Huang SM, Kaner RB, Fu KJ, Whetten RL, Diederich F. 1991. Alkali-fulleride superconductors: synthesis, composition, and diamagnetic shielding. Science 252, 1154–1157. ( 10.1126/science.252.5009.1154) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleming RM, Ramirez AP, Rosseinsky MJ, Murphy DW, Haddon RC, Zahurak SM, Makhija AV. 1991. Relation of structure and superconducting transition temperatures in A3C60. Nature 352, 787–788. ( 10.1038/352787a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanigaki K, Ebbesen TW, Saito S, Mizuki J, Tsai JS, Kubo Y, Kuroshima S. 1991. Superconductivity at 33 K in CsxRbyC60. Nature 352, 222–223. ( 10.1038/352222a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stephens PW, Mihaly L, Lee PL, Whetten RL, Huang SM, Kaner R, Deiderich F, Holczer K. 1991. Structure of single-phase superconducting K3C60. Nature 351, 632–634. ( 10.1038/351632a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prassides K, Christides C, Thomas IM, Mizuki J, Tanigaki K, Hirosawa I, Ebbesen TW. 1994. Crystal structure, bonding, and phase transition of the superconducting Na2CsC60 fulleride. Science 263, 950–954. ( 10.1126/science.263.5149.950) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown CM, Takenobu T, Kordatos K, Prassides K, Iwasa Y, Tanigaki K. 1999. Pressure dependence of superconductivity in the Na2Rb0.5Cs0.5C60 fulleride. Phys. Rev. B 59, 4439–4444. ( 10.1103/PhysRevB.59.4439) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schluter M, Lannoo M, Needles M, Baraff GA. 1992. Electron–phonon coupling and superconductivity in alkali-intercalated C60 solid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 526–529. ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.68.526) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prassides K, Tomkinson J, Christides C, Rosseinsky MJ, Murphy DW, Haddon RC. 1991. Vibrational spectroscopy of superconducting K3C60 by inelastic neutron scattering. Nature 354, 462–463. ( 10.1038/354462a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chakravarty S, Gelfand MP, Kivelson S. 1991. Electronic correlation effects and superconductivity in doped fullerenes. Science 254, 970–974. ( 10.1126/science.254.5034.970) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keimer B, Kivelson SA, Norman MR, Uchida S, Zaanen J. 2015. From quantum matter to high-temperature superconductivity in copper oxides. Nature 518, 179–186. ( 10.1038/nature14165) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knebel G, Aoki D, Braithwaite D, Salce B, Flouquet J. 2006. Coexistence of antiferromagnetism and superconductivity in CeRhIn5 under high pressure and magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 74, 020501 ( 10.1103/PhysRevB.74.020501) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ardavan A, Brown S, Kagoshima S, Kanoda K, Kuroki K, Mori H, Ogata M, Uji S, Wosnitza J. 2012. Recent topics of organic superconductors. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 81, 011004 ( 10.1143/JPSJ.81.011004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lof RW, VanVeenendaal MA, Koopmans B, Jonkman HT, Sawatzky GA. 1992. Band gap, excitons, and Coulomb interaction in solid C60. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 3924–3927. ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.68.3924) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koch E, Gunnarsson O, Martin RM. 1999. Screening, Coulomb pseudopotential, and superconductivity in alkali-doped fullerenes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 620–623. ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.620) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capone M, Fabrizio M, Castellani C, Tosatti E. 2002. Strongly correlated superconductivity. Science 296, 2364–2366. ( 10.1126/science.1071122) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanigaki K, Prassides K. 1995. Conducting and superconducting properties of alkali-metal C60 fullerides. J. Mater. Chem. 5, 1515–1527. ( 10.1039/jm9950501515) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gunnarsson O. 1997. Superconductivity in fullerides. Rev. Mod. Phys. 69, 575–606. ( 10.1103/RevModPhys.69.575) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prassides K. 1997. Fullerenes. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2, 433–439. ( 10.1016/S1359-0286(97)80085-X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosseinsky MJ. 1998. Recent developments in the chemistry and physics of metal fullerides. Chem. Mater. 10, 2665–2685. ( 10.1021/cm980226p) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kosaka M, Tanigaki K, Prassides K, Margadonna S, Lappas A, Brown CM, Fitch AN. 1999. Superconductivity in LixCsC60 fullerides. Phys. Rev. B 59, R6628–R6630. ( 10.1103/PhysRevB.59.R6628) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forró L, Mihály L. 2001. Electronic properties of doped fullerenes. Rep. Prog. Phys. 64, 649–700. ( 10.1088/0034-4885/64/5/202) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Margadonna S, Prassides K. 2002. Recent advances in fullerene superconductivity. J. Solid State Chem. 168, 639–652. ( 10.1006/jssc.2002.9762) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iwasa Y, Takenobu T. 2003. Superconductivity, Mott–Hubbard states, and molecular orbital order in intercalated fullerides. J. Phys: Condens. Matter 15, R495–R520. ( 10.1088/0953-8984/15/13/202) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gunnarsson O. 2004. Alkali-doped fullerides: narrow-band solids with unusual properties. Singapore: World Scientific. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Margadonna S, Iwasa Y, Takenobu T, Prassides K. 2004. Structural and electronic properties of selected fulleride salts. Struct. Bond. 109, 127–164. ( 10.1007/b94381) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gunnarsson O, Han JE, Koch E, Crespi VH. 2005. Superconductivity in alkali-doped fullerides. Struct. Bond. 114, 71–101. ( 10.1007/b101017) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosseinsky MJ, Murphy DW, Fleming RM, Zhou O. 1993. Intercalation of ammonia into K3C60. Nature 364, 425–427. ( 10.1038/364425a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takenobu T, Muro T, Iwasa Y, Mitani T. 2000. Antiferromagnetism and phase diagram in ammoniated alkali fulleride salts. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 381–384. ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.381) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Margadonna S, Prassides K, Shimoda H, Takenobu T, Iwasa Y. 2001. Orientational ordering of C60 in the antiferromagnetic (NH3)K3C60 phase. Phys. Rev. B 64, 132414 ( 10.1103/PhysRevB.64.132414) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ganin AY, Takabayashi Y, Bridges CA, Khimyak YZ, Margadonna S, Prassides K, Rosseinsky MJ. 2006. Methylaminated potassium fulleride, (CH3NH2)K3C60: towards hyperexpanded fulleride lattices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 14 784–14 785. ( 10.1021/ja066295j) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prassides K, Margadonna S, Arčon D, Lappas A, Shimoda H, Iwasa Y. 1999. Magnetic ordering in the ammoniated fulleride (ND3)K3C60. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 11 227–11 228. ( 10.1021/ja992931k) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takabayashi Y, Ganin AY, Rosseinsky MJ, Prassides K. 2007. Direct observation of magnetic ordering in the (CH3NH2)K3C60 fulleride. Chem. Commun. 870–872. ( 10.1039/B614596E) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arvanitidis J, Papagelis K, Takabayashi Y, Takanobu T, Iwasa Y, Rosseinsky MJ, Prassides K. 2007. Magnetic ordering in the ammoniated alkali fullerides (NH3)K3−xRbxC60 (x = 2,3). J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 19, 386235 ( 10.1088/0953-8984/19/38/386235) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takabayashi Y, Prassides K. 2016 The renaissance of fullerene superconductivity. Struct. Bond. ( 10.1007/430_2015_207) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ganin AY, Takabayashi Y, Khimyak YZ, Margadonna S, Tamai A, Rosseinsky MJ, Prassides K. 2008. Bulk superconductivity at 38 K in a molecular system. Nat. Mater. 7, 367–371. ( 10.1038/nmat2179) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ganin AY. et al. 2010. Polymorphism control of superconductivity and magnetism in Cs3C60 close to the Mott transition. Nature 466, 221–225. ( 10.1038/nature09120) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ihara Y, Alloul H, Wzietek P, Pontiroli D, Mazzani M, Riccò M. 2010. NMR study of the Mott transitions to superconductivity in the two Cs3C60 phases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 256402 ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.256402) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takabayashi Y. et al. 2009. The disorder-free non-BCS superconductor Cs3C60 emerges from an antiferromagnetic insulator parent state. Science 323, 1585–1590. ( 10.1126/science.1169163) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zadik RH. et al. 2015. Optimized unconventional superconductivity in a molecular Jahn–Teller metal. Sci. Adv. 1, e150059 ( 10.1126/sciadv.1500059) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Darling GR, Ganin AY, Rosseinsky MJ, Takabayashi Y, Prassides K. 2008. Intermolecular overlap geometry gives two classes of fulleride superconductor: electronic structure of 38 K Tc Cs3C60. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 136404 ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.136404) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kasahara Y. et al. 2014. Spin frustration and magnetic ordering in the S=1/2 molecular antiferromagnet fcc-Cs3C60. Phys. Rev. B 90, 014413 ( 10.1103/PhysRevB.90.014413) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han JE, Gunnarsson O, Crespi VH. 2003. Strong superconductivity with local Jahn–Teller phonons in C60 solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 167006 ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.167006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Capone M, Fabrizio M, Castellani C, Tosatti E. 2009. Colloquium: Modeling the unconventional superconducting properties of expanded A3C60 fullerides. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 943–958. ( 10.1103/RevModPhys.81.943) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Akashi R, Arita R. 2013. Nonempirical study of superconductivity in alkali-doped fullerides based on density functional theory for superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 88, 054510 ( 10.1103/PhysRevB.88.054510) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murakami Y, Werner P, Tsuji N, Aoki H. 2013. Ordered phases in the Holstein–Hubbard model: interplay of strong Coulomb interaction and electron–phonon coupling. Phys. Rev. B 88, 125126 ( 10.1103/PhysRevB.88.125126) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nomura Y, Sakai S, Capone M, Arita R. 2015. Unified understanding of superconductivity and Mott transition in alkali-doped fullerides from first principles. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500568 ( 10.1126/sciadv.1500568) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klupp G, Matus P, Kamarás K, Ganin AY, McLennan A, Rosseinsky MJ, Takabayashi Y, McDonald TM, Prassides K. 2012. Dynamic Jahn–Teller effect in the parent insulating state of the molecular superconductor Cs3C60. Nat. Commun. 3, 912 ( 10.1038/ncomms1910) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Potočnik A. et al. 2014. Jahn–Teller orbital glass state in the expanded fcc Cs3C60 fulleride. Chem. Sci. 5, 3008–3017. ( 10.1039/C4SC00670D) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Potočnik A, Krajnc A, Jeglič P, Takabayashi Y, Ganin AY, Prassides K, Rosseinsky MJ, Arčon D. 2014. Size and symmetry of the superconducting gap in the f.c.c. Cs3C60 polymorph close to the metal–Mott insulator boundary. Sci. Rep. 4, 4265 ( 10.1038/srep04265) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wzietek P, Mito T, Alloul H, Pontiroli D, Aramini M, Riccò M. 2014. NMR study of the superconducting gap variation near the Mott transition in Cs3C60. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 066401 ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.066401) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tanaka K. et al. 2006. Distinct Fermi-momentum-dependent energy gaps in deeply underdoped Bi2212. Science 314, 1910–1913. ( 10.1126/science.1133411) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu Y-M. et al. 2011. Fermi surface dichotomy of the superconducting gap and pseudogap in underdoped pnictides. Nat. Commun. 2, 392 ( 10.1038/ncomms1394) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

57.Christides C, Neumann DA, Prassides K, Copley JRD, Rush JJ, Rosseinsky MJ, Murphy DW, Haddon RC.

1992.

Neutron-scattering study of C

(n=3,6) librations in alkali-metal fullerides. Phys. Rev. B

46, 12 088–12 091. ( 10.1103/PhysRevB.46.12088) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

(n=3,6) librations in alkali-metal fullerides. Phys. Rev. B

46, 12 088–12 091. ( 10.1103/PhysRevB.46.12088) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - 58.Jiang H-C, Kivelson S. 2015. Electronic pair-binding and Hund’s rule violations in doped C60. Phys. Rev. B 93, 165406 ( 10.1103/PhysRevB.93.165406) [DOI] [Google Scholar]