Abstract

Male and female reproductive behaviors in Drosophila melanogaster are vastly different, but neurons that express sex-specifically spliced fruitless transcripts (fru P1) underlie these behaviors in both sexes. How this set of neurons can generate such different behaviors between the two sexes is an unresolved question. A particular challenge is that fru P1-expressing neurons comprise only 2–5% of the adult nervous system, and so studies of adult head tissue or whole brain may not reveal crucial differences. Translating Ribosome Affinity Purification (TRAP) identifies the actively translated pool of mRNAs from fru P1-expressing neurons, allowing a sensitive, cell-type-specific assay. We find four times more male-biased than female-biased genes in TRAP mRNAs from fru P1-expressing neurons. This suggests a potential mechanism to generate dimorphism in behavior. The male-biased genes may direct male behaviors by establishing cell fate in a similar context of gene expression observed in females. These results suggest a possible global mechanism for how distinct behaviors can arise from a shared set of neurons.

Keywords: sex differences, courtship behaviors, Drosophila, sex hierarchy, fruitless, genetics of sex

Adult reproductive behaviors in Drosophila melanogaster are directed predominately by a set of neurons that express sex-specifically spliced fruitless transcripts (fru P1 transcripts) (Ito et al. 1996; Ryner et al. 1996; Demir and Dickson 2005; Manoli et al. 2005; Stockinger et al. 2005; Dickson 2008; and reviewed in Siwicki and Kravitz 2009). These neurons are largely detected as dispersed clusters, comprising ∼2–5% of neurons in the central and peripheral nervous system, of both males and females (Lee et al. 2000; Manoli et al. 2005; Stockinger et al. 2005). The positions and number of fru P1-expressing neurons are notably similar in males and females, though there are evident differences in neuronal arborization volume, neuron number, and physiology (Kimura et al. 2005; Manoli et al. 2005; Stockinger et al. 2005; Datta et al. 2008; Cachero et al. 2010; Yu et al. 2010; Ito et al. 2012; Kohl et al. 2013; and reviewed in Yamamoto and Koganezawa 2013).

How sex-specific differences arise in a set of neurons with a shared developmental trajectory and genome to ultimately direct the distinct adult behaviors is not understood. Additionally, in terms of gene expression, it is not known what is common to both male and female fru P1-expressing neurons, and whether that is distinct from other neurons. To address these questions, we leverage a molecular-genetic tool that allows enrichment of mRNAs resident in ribosomes (Thomas et al. 2012), in a cell-type-specific manner, to discover the characteristics of the translatome of male and female fru P1-expressing neurons.

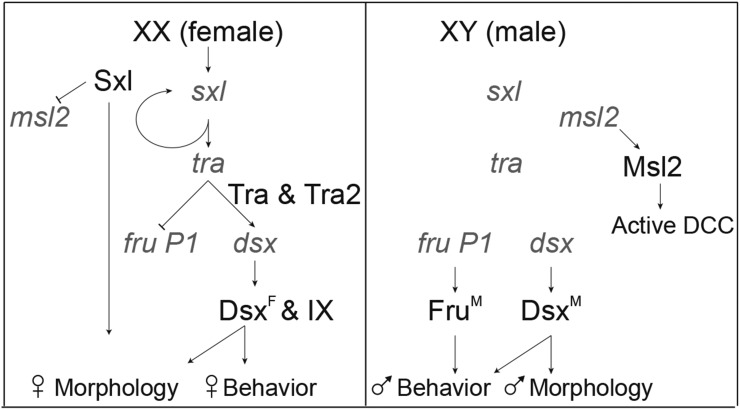

In Drosophila, adult reproductive behaviors are regulated downstream of the sex hierarchy, an alternative pre-mRNA splicing cascade, responsive to the number of the X chromosomes, that directs the production of sex-specific transcription factors encoded by fruitless (fru) and doublesex (dsx) (see Figure 1) (reviewed in Yamamoto 2007; Villella and Hall 2008). fru is a complex locus that has multiple promoters, with the fru P1 promoter directing production of the transcripts that are sex-specifically alternatively spliced (Ito et al. 1996; Ryner et al. 1996). This splicing results in production of male-specific isoforms (FruM) (reviewed in Manoli et al. 2006; Dauwalder 2011). There is an early stop codon in the female-specific fru P1 transcript, and so there is no functional product predicted (Usui-Aoki et al. 2000). dsx directs sex differences in body morphology, and also plays a role in the nervous system to specify the potential for reproductive behaviors, with some overlap in expression with fru P1 (Lee et al. 2002; Rideout et al. 2007; Kimura et al. 2008; Sanders and Arbeitman 2008; Rideout et al. 2010; Robinett et al. 2010; and reviewed in Yamamoto and Koganezawa 2013).

Figure 1.

Drosophila sex determination hierarchy. In Drosophila differences in somatic tissues are directed by the sex determination hierarchy. In response to the number of X chromosomes, alternative pre-mRNA splicing occurs at the top of the hierarchy (sxl, tra and tra-2 are splicing factors that direct alternative pre-mRNA splicing of dsx and fru P1), leading to sex-specific production of Dsx and Fru transcription factors. In females, production of Sxl also inhibits translation of msl2, resulting in the absence of dosage compensation in females, as the dosage compensation complex (DCC) is not formed in the absence of MSL2. In females, DsxF together with Ix regulate gene expression to direct female-specific behavior, morphology, and physiology. In males, DsxF and FruM regulate gene expression to direct male-specific behavior, morphology, and physiology.

Several studies have demonstrated that the neurons that express fru P1 in males are important for the elaborate male courtship display (Ito et al. 1996; Ryner et al. 1996; Villella et al. 1997; Anand et al. 2001; Lee et al. 2001; Demir and Dickson 2005; Manoli et al. 2005; von Philipsborn et al. 2011; reviewed in Yamamoto and Koganezawa 2013; Tran et al. 2014; Zhou et al. 2015). fru P1-expressing neurons also direct female reproductive behaviors, including receptivity to mating, egg laying, food preference after mating, and rejection behaviors (Kvitsiani and Dickson 2006; Yapici et al. 2008; Hasemeyer et al. 2009; Yang et al. 2009). How fru P1-expressing neurons drive both male and female adult behavior is not understood. We hypothesize that these neurons translate a different set of proteins in males and females. Our study focuses on the translatome, as this is currently one of the only ways to assess the differences in the protein production specifically in fru P1-expressing neurons.

Here, we identify mRNAs that are enriched in the translatome of male and female fru P1-expressing neurons in 16- to 24-hr adults, using the Translating Ribosome Affinity Purification (TRAP) method (for review and discussion of cell-specific tools see Tallafuss et al. 2014). We drive expression of the GFP-tagged variant of RpL10A in fru P1-expressing neurons, using Gal4 driven by the fru P1 promoter (Manoli et al. 2005; Thomas et al. 2012). We analyze five independent biological replicates to increase our power to detect significant differences in gene expression (Liu et al. 2014). We identify sex-differences in the translatome of fru P1-expressing neurons, with the majority of genes showing male-biased transcript abundance. We also identify genes with products that are present in the ribosome of both sexes, which we find are distinct from those that are enriched in all neurons of the adult head, also identified using the TRAP approach (Thomas et al. 2012). This may be because fru P1-expressing neurons are a small subset of all neurons. The results point to the importance of understanding the translatome in a cell-type-specific manner. An immediate question suggested by these findings is how much of this male-biased TRAP mRNA is a result of the FruM protein itself, as this protein is made only in males. To address this, we compare the results of this study to our previous analyses aimed at identifying targets of FruM (Dalton et al. 2013).

Materials and Methods

Flies

Flies were raised on standard cornmeal food medium at 25° on a 12-hr light and 12-hr dark cycle. Flies that express the GFP-tagged variant of RpL10A in fru P1-expressing neurons are the genotypes: w/(w or Y); P[w+mC, UAS-Gal4]/P[w+mC, UAS-GFP::RpL10A]; fru P1-Gal4/+ (Manoli et al. 2005; Thomas et al. 2012). We note that this fru P1-Gal4 allele has been shown to masculinize the female nervous system when homozygous, but in this study it is heterozygous (Ferri et al. 2008).

Tissue collection

Libraries were prepared from five independent biological replicates for each condition. For each replicate, approximately 1000 flies that were 16- to 24-hr posteclosion were used. All flies were collected 0–8 hr posteclosion under anesthetization, and allowed to recover for 16 hr before being snap frozen in liquid nitrogen between ZT1 and ZT2. Snap-frozen whole animals were stored at –80° until heads were collected. Frozen adult heads were separated from bodies by vigorous vortexing and collected using chilled mesh sieves #25 and #40 to separate out the bodies and heads, respectively.

Polysome immunoprecipitation

Translated mRNA purification was performed as previously described (Doyle et al. 2008; Heiman et al. 2008; Thomas et al. 2012; Heiman et al. 2014), with the following modifications: approximately 1000 heads per replicate were collected and homogenized in lysis buffer [20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 100 μg/ml Cyclohexamide, 100 U/ml RNaseOUT (Invitrogen), 1 × Complete Protease Inhibitor (Roche)]. The sample was centrifuged at 4° for 10 min at 2000 × g and the supernatant was collected. 1,2-diheptanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DHPC; Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc.) and NP-40 were added to a final concentration of 30 mM and 1%, respectively, to the supernatant and incubated on ice for 5 min. The lysate was then centrifuged at 4° for 10 min at 20,000 × g; 40 μl of the supernatant was retained and placed directly into 200 μl of Lysis Solution [Ambion MicroPoly(A) Purist Kit] to be used to analyze the input RNA fraction. The remaining supernatant was added to Dynabeads Protein G magnetic beads (Novex) conjugated to mouse anti-GFP (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Monoclonal Antibody Facility19C8/19F7). The lysate-bead slurry was incubated for 30 min at 4° followed by washing in Wash Buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2, 350 mM KCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5 mM DTT, and 100 μg/ml Cyclohexamide) at 4°. The IP was resuspended in Lysis Solution [Ambion MicroPoly(A) Purist Kit] and mRNA was directly isolated following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Illumina sequencing library preparation

Poly(A)+ transcripts were isolated using Ambion MicroPoly(A)Purist Kit. mRNA was chemically fragmented to a range of approximately 200–500 bp using the Ambion RNA Fragmentation Reagent, and the RNA was purified using Zymo Research RNA Clean & Concentrator-5. First strand cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) and a combination of 3 µg random hexamers and 0.15 µg oligo(dT)20 primers. Following first strand synthesis, the second strand of the cDNA was synthesized by addition of DNA polymerase I (Invitrogen), RNase H (New England Biolabs Inc.), dNTPs and second strand buffer (Invitrogen). The DNA from this and all subsequent reactions was purified using Zymo Research DNA Clean & Concentrator-5 kit. Double-stranded cDNA templates were blunt ended using End-It Repair Kit (Epicentre). Next, A-overhangs were added to both ends with Klenow fragment (3′→5′ exo-minus) (New England Biolabs Inc.). Illumina sequencing adapters were then ligated to both ends of the cDNA templates using Fast-Link DNA Ligation Kit (Epicentre). cDNA templates were amplified by performing polymerase chain reaction (PCR; 18 cycles), which extended the adapter and incorporated a different six base pair index into each sample. The product was isolated by gel purification of 250–550 bp fragments. Samples were pooled and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform with 100-bp single end reads, and the reads were matched to their corresponding sample via the index.

Illumina read alignment

Distinct reads (nonduplicate) were aligned to FB5.51 (FlyBase Version 5.51) using Bowtie (Langmead et al. 2009) (Version 1.9; -m1 -v3) and LAST (Frith et al. 2010) (Version 247; -l 25). Coverage was calculated as Reads Per Kilobase per Million, RPKM (Mortazavi et al. 2008), which adjusts for number of reads mapped and region length. Exonic regions with at least one read present for at least half of the replicates for each treatment were analyzed further. Exonic regions with no coverage in all replicates, and those with no coverage in half or more of the replicates for one treatment condition were removed from the analysis. The natural log of the RPKM was taken.

Differential gene expression

In this study, differential abundance was determined for each exon separately and then existing gene models were used to make determinations about differential abundance of transcript isoforms, as we have previously done (Dalton et al. 2013). We report that a gene is differentially expressed if at least one exon from the gene has significant differential expression in the comparison.

Differential gene expression was tested using a linear model where Yij = μ + ti + εij where Y is the log transformed RPKM for the ith condition (i = male input (MI), Female input (FI), male TRAP (MT), female TRAP (FT)) and jth replicate (j = 1,...,5) the residuals were modeled as ei ∼N(0,σ2i) (Law et al. 2014). This accounts for heteroscedasticity (unequal variance) of variances. While not commonly addressed in most RNA-seq studies, this issue is underappreciated and worth serious consideration (Law et al. 2014). In these types of experiments, such differences in variances are not unexpected. After the model was determined to fit well for most exons, the following contrasts were performed: μMT = μMI; μFT = μFI; μMT – μMI = μFT – μFI; μMT = μFT; μMI – μFI. All of the contrasts were considered simultaneously in a false discovery rate (FDR) correction (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). An FDR p-value of ≤ 0.2 was considered significant. The FDR is the proportion of rejections that are expected to be false positives. As with the family-wise error rate, decreasing the FDR results in increasing the FNR (false nondiscovery rate). Due to concerns about type II error, a more liberal FDR was used. The results are similar at lower levels of the FDR, and the full results table of all tests performed is provided with raw and adjusted p-values (Supplemental Material, Table S1 and Table S2).

Motif analysis

MAST (Bailey and Gribskov 1998) uses a file of motifs (FruA, B, and C DNA binding motifs determined using SELEX), and a sequence FASTA file to identify Fru binding sites in a region that includes the gene of interest, 2 kb upstream of the transcription start site, and 2 kb downstream of the 3′UTR. All analyses were conducted in SAS.

Enrichment analyses

Targeted comparisons were made using a Fisher’s exact test (Beissbarth and Speed 2004). We tested whether there is a significant association of the FruM regulated genes, as previously determined (Dalton et al. 2013), with the male-biased genes identified here. We also tested whether genes regulated by FruM and male-biased were significantly enriched on a chromosome. A Fisher’s exact test was used to test for enrichment of the Fru binding sites for the A, B, and C DNA binding domains.

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed using the Gene Ontology Enrichment portal in Flymine v42.1 (Lyne et al. 2007). Target list containing FBgns of genes in each list were supplied against the default background list. GO terms, associated p-values, and associated genes for biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions with a Benjamini-Hochberg corrected p-value cut-off of < 0.05 were compiled for each list. Enriched protein domain analysis was also implemented with the Benjamini-Hochberg correction in the Flymine portal with a p-value cut-off of < 0.05 (Lyne et al. 2007). Tissue analyses to identify Drosophila tissues with the largest number of genes with significantly high expression were done by comparison to the FlyAtlas data set (Chintapalli et al. 2007; Robinson et al. 2013).

Data availability

The accession number for the data is: GSE67743 at the Gene Expression Omnibus.

Results

This study identifies the transcripts that are actively translated in fru P1 neurons of males and females, with the goal of providing insight into the complement of protein differences between the sexes in neurons that control sex-specific behaviors. Translating ribosome affinity purification (TRAP) was used to enrich for transcripts from the actively translated mRNA pool in fru P1-expressing neurons, from 16- to 24-hr adult male and female head tissues. RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) was performed on five independent biological replicates, to identify transcripts with differences in abundance, on a genome-wide level, with exon-specific resolution (see Figure S1 for exon-level mapping, and Graze et al. 2012).

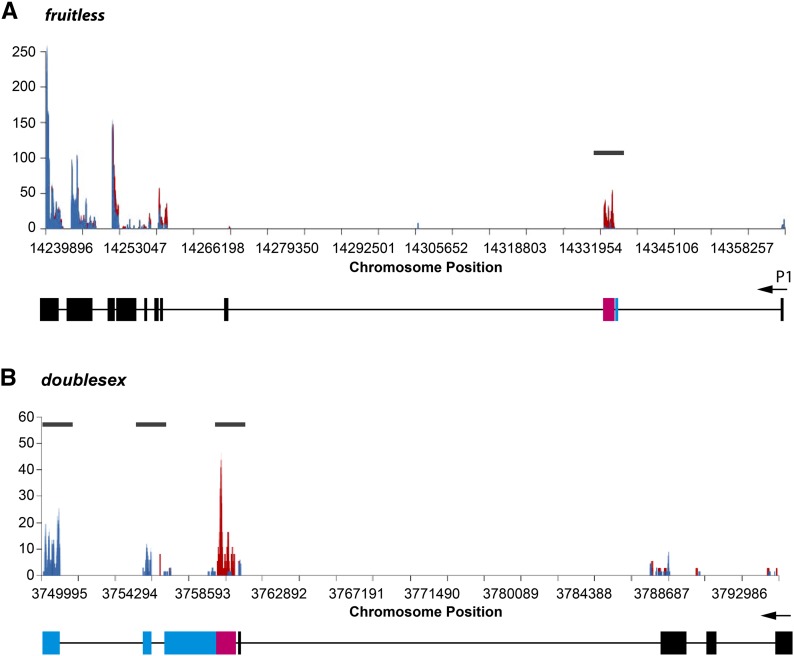

Overview of the genes detected in input and TRAP samples

We determined that the TRAP technique is working effectively in fru P1-expressing neurons. First, we observe that fru transcripts are enriched in male and female TRAP samples relative to the input, as we would expect, given that we are using fru P1-Gal4 to drive expression of the tagged ribosome subunit for purification. However, fru also encodes transcripts expressed outside of the fru P1-expressing domain, and all fru transcripts share common exons (Ryner et al. 1996). Thus, we do not expect all fru exons to be enriched in the TRAP samples. Four fru exons are 1.5-fold higher in male TRAP samples vs. male total RNA input, with two statistically significantly higher. One exon is 1.5-fold higher in female TRAP samples vs. female RNA input and is statistically significantly higher. The exon that is sex-specifically spliced under sex-hierarchy control is statistically significantly higher in the female TRAP samples compared to the male TRAP samples, as expected given the length difference (see Figure S1 and Figure 2). These results underscore the importance of examining expression at the exon level.

Figure 2.

TRAP sequencing read coverage of dsx and fru. Average normalized read coverage (Y axis) across the (A) fru and (B) dsx loci from male (blue) and female (red) TRAP samples aligned to the gene structure. For both fru and dsx, the 5′ end of the transcript is on the right. The gray bar above the count data indicates where there are sex-differences in retention of an exon, because of sex hierarchy regulated alternative pre-mRNA splicing. fru has at least 15 different transcripts, and dsx has at least six different transcripts (Attrill et al. 2016).

Additionally, though fru P1 and dsx are among genes with relatively low mRNA abundance in the adult head (Chang et al. 2011), and are not always consistently detected in gene expression studies (Fear et al. 2015), we detect the transcripts, as well as sex-specific differences in splicing (Figure 2), demonstrating the enhanced sensitivity of the technique. We define a detected gene as > 50% of the replicates having at least one exon with at least one sequence read. In this study, 12,442 genes had sequence read coverage, with 12,439 genes detected in the whole head input RNA and 9030 genes detected in the TRAP samples (Table S3). There are 3412 genes that are detected only in the input (Table S3).

Of the 9030 genes detected in the TRAP samples, 8700 are detected in the male TRAP samples and 8297 are detected in the female TRAP samples (Table S3). A similar number of genes was detected in fru P1 TRAP samples, as detected in the entire head in previous studies using Illumina sequencing (9473, Chang et al. 2011) and microarrays (7411, King et al. 2012). The TRAP samples have fewer genes detected than the input samples in this study, which is expected, as we are enriching for transcripts from genes expressed in fru P1-expressing neurons, whereas whole head samples include other tissue-types, including fat body and muscle. The increase in genes detected overall is likely due to a combination of the increased number of replicates and improvement in technology leading to higher sequencing depth. Thus, TRAP is clearly effective here, and can be used to understand the properties of the fru P1 translatome.

Gene expression differences between male and female adult head tissues

We wanted to determine how many genes have sex-specific or sex-biased expression in the input RNA, using exon-level analysis, in contrast to our previous studies where we report sex-differences in expression levels in adult head tissues using gene-level analyses (Goldman and Arbeitman 2007; Chang et al. 2011). In this study, 1537 genes have exons that are detected only in input from males, and 294 genes have exons that are detected only in input from females (Table S3). Based on statistical comparisons, we find 1438 (male-biased) and 1125 (female-biased) genes have significant, sex-biased expression in the input mRNA (Figure 3, Table 1, and Table S4). Previously our gene-level, RNA-seq analyses found 815 (male) and 566 (female) genes with significant, sex-biased expression (Chang et al. 2011). If we examine the overlap between the two studies, there are 250 male-biased and 214 female-biased genes identified in both studies (Table S4). This difference is not unexpected; the two studies differ in strain background, which has a large impact on sex-biased expression (Catalan et al. 2012; Arbeitman et al. 2016). We also note that detecting overlap between the two studies is sensitive to our ability to statistically detect expression differences. The genes that are sex-biased in both studies include those with an enrichment of genes with functions in the synapse (male-biased), ribosome and mitotic spindle (female-biased), based on GO analyses (Table S5). There are 20 genes with evidence for sex-specific exon usage (Table 1, Figure 3, and Table S4). This is evidence for alternative transcript isoform usage in males and females—a result consistent with previous studies of the whole body (McIntyre et al. 2006) and the head (Telonis-Scott et al. 2009; Graze et al. 2012).

Figure 3.

Gene and exon expression differences between males and females in input and TRAP samples. (A) Comparison of log mean RPKM values of male and female input mRNA samples. (B) Comparison of genes with male-biased (blue) and female-biased (pink) expression in input mRNA samples. (C) Comparison of log mean RPKM values of male and female TRAP samples. (D) Comparison of genes with male-biased (blue) and female-biased (pink) TRAP enrichment. A gene can be both male-biased and female-biased if different exons for that gene showed male-biased or female-biased expression. In (A) and (C), exons that were not statistically tested (gray, NA), exons that were not significant (black, NS), exons that were significantly different at an FDR value of < 0.20 (blue), and exons that were significantly different at an FDR value of < 0.05 (orange), are indicated.

Table 1. Differences between male and female input mRNA.

| Description | Exons | Genes | GO: Biological Processa | GO: Cellular Componenta | GO: Molecular Functiona | Protein Domaina | Tissue Expression (# of Genes)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male-biased in input mRNA | 1956 | 1438 | Synaptic transmission | Synapse | Cytoskeletal binding protein | SH3 domain | Brain (881) |

| Signaling | Presynapse | PDZ domain | Larval CNS (872) | ||||

| Regulation of neurotransmitter levels | Voltage-dependent channel | Thor. Gang (843) | |||||

| Female-biased in input mRNA | 1710 | 1125 | Mitotic spindle elongation | Ribosomal subunit | Structural constituent of ribosome | EGF-like domain | Adult carcass (603) |

| Ribosome biogenesis | Adult fat body (563) | ||||||

| Mated Spermathecae (556) | |||||||

| Sex-specific exon usage | 20 |

Gene Ontology (GO) terms and protein domain enrichments were among the most significant for each list.

The three fly tissues that had the largest number of genes with significantly high expression in the FlyAtlas data set.

Genes with fru P1 translatome mRNA enrichment relative to input

Next, we wanted to identify the genes that are different between the male and female TRAP samples relative to the input RNA from the same sex. It should be noted that genes expressed in fru P1-expressing neurons are likely to be expressed in other cells/neurons of the head, so we do not expect all genes expressed in fru P1-expressing neurons to be enriched in the TRAP samples relative to the input (for example see Dalton et al. 2009). In this analysis, the null hypothesis is that there is no difference between input and TRAP samples. Further, for an exon to be declared significantly enriched in the TRAP samples, the abundance needed to be higher in the TRAP sample compared to input from the same sex.

We identified 772 genes that are higher in male TRAP samples compared to the male input and 408 genes that are higher in the female TRAP samples compared to the female input (Table 2 and Table S6). These genes are enriched with those that encode neuropeptide receptors, signaling molecule and neurotransmitter secretion products (Table 2). Of these, 476 genes had higher expression in male TRAP only; 112 genes had higher expression in female TRAP only; and 296 genes have higher expression in TRAP samples in both sexes (Table S6). There are 11 genes with evidence for sex-specific exon enrichment in TRAP relative to input mRNA (Table S6).

Table 2. fru P1 TRAP mRNA enrichment relative to input mRNA.

| Description | Exons | Genes | GO: Biological Processa | GO: Cellular Componenta | GO: Molecular Functiona | Protein Domaina | Tissue Expression (# of Genes)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enriched in male TRAP relative to male input mRNA | 855 | 772 | Signaling | Synapse | Neuropeptide receptor binding | Pleckstrin homology domain | Thor. Gang (471) |

| Synaptic transmission | Neuron part | Hormone activity | C2 domain | Brain (470) | |||

| Neurotransmitter secretion | Axon | Nucleotide binding | Larval CNS (431) | ||||

| Enriched in female TRAP relative to female input mRNA | 447 | 408 | Signaling | Synapse | Neuropeptide receptor binding | M1F4G-like domain | Thor. Gang (275) |

| Synaptic transmission | Neuron part | Hormone activity | Brain (240) | ||||

| Neurotransmitter secretion | Axon | Nucleotide binding | Larval CNS (230) | ||||

| Enriched in TRAP relative to input mRNA in both sexes | 310 | 296 | Signaling | Synapse | Neuropeptide receptor binding | Thor. Gang (183) | |

| Synaptic transmission | Neuron part | Hormone activity | Brain (177) | ||||

| Neurotransmitter secretion | Axon | G-coupled protein receptor binding | Head (167) | ||||

| Uniquely enriched in male TRAP relative to male input mRNA | 545 | 476 | Signal transduction | Organelle | Pleckstrin homology domain | Brain (293) | |

| Signaling | Synapse | Oxysterol-binding protein | Thor. Gang (288) | ||||

| Cell communication | Neuron part | Larval CNS (268) | |||||

| Uniquely enriched in female TRAP relative to female input mRNA | 137 | 112 | Larval CNS (67) | ||||

| Brain (63) | |||||||

| Thor. Gang (62) | |||||||

| Sex-specific exon enrichment in TRAP relative to input mRNA | 11 |

Gene Ontology (GO) terms and protein domain enrichments were among the most significant for each list.

The three fly tissues that had the largest number of genes with significantly high expression in the FlyAtlas data set.

We performed visual inspection of plots showing count distributions along the gene models for the 11 genes predicted to have different transcript isoforms enriched in the male and female TRAP samples. The plots show quantitative differences in count abundance between the male and female exons in the TRAP samples, with the exon detected in both male and female TRAP samples. However, Hr51, Pkc53E, and CG42684 have exons that have mapped reads only in one sex (Figure S2), suggesting that there are sex-specific transcript isoforms in fru P1-expressing neurons. For example, Hr51 has three internal exons that have reads in the male TRAP, but not in the female TRAP samples; this coincides with our previous findings that Hr51 is regulated by FruM (Dalton et al. 2013). These data indicate that sexual dimorphism in the translatome in male and female fru P1-expressing neurons are due, at least in part, to different transcript isoform usage.

Differences in the translatome of fru P1-expressing neurons between males and females

To identify all significant differences in mRNAs that are actively translated in fru P1 neurons between males and females, we identified the sets of genes with exons that have significantly different RNA-seq abundance between the fru P1-expressing TRAP samples from males and females. There are 1210 genes that are male-biased in the TRAP samples, and 331 genes that are female-biased (Figure 3, Table 3, and Table S7). There are 16 genes with exons whose bias is dependent on the particular exon/isoform examined, giving further evidence for differences in transcript isoforms in the male and female TRAP samples (Figure 3D, Table 3, and Table S7). fru is one of the genes we detect as having differences in transcript isoforms in the TRAP samples, as expected (Table S7). There are 19 genes of the 1210 male-biased genes that are annotated with the GO term male courtship behavior (Table S5), including dissatisfaction (dsf), which has been previously been implicated in underlying male courtship behavior (Finley et al. 1998).

Table 3. Differences between male and female TRAP mRNA.

| Description | Exons | Genes | GO: Biological Processa | GO: Cellular Componenta | GO: molecular functiona | Protein Domaina | Tissue Expression (# of Genes)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male-biased TRAP mRNA | 1420 | 1210 | Signaling | Synapse | Ion binding | PDZ domain | Brain (732) |

| Development | Cell junction | Cytoskeletal binding | SH3 domain | Larval CNS (723) | |||

| Synaptic transmission | Presynapse | Pleckstrin homology domain | Thor. Gang (700) | ||||

| Female-biased TRAP mRNA | 415 | 331 | Mitotic spindle | Ribosomal subunit | Structural constituent of ribosome | Adult carcass (182) | |

| translation | Adult heart (172) | ||||||

| Head (162) | |||||||

| Sex-biased exon | 16 |

Gene Ontology (GO) terms and protein domain enrichments were among the most significant for each list.

The three fly tissues that had the largest number of genes with significantly high expression in the FlyAtlas data set.

Additionally, we determined how many genes are detected in TRAP samples from both males and females, and find 7967 genes (hereafter called core genes; Table S3). These core genes are significantly enriched with those that encode proteins with the Immunoglobulin-fold domain (163 genes; Table S5). We previously found genes encoding proteins with this domain were highly enriched in the gene sets identified as regulated by FruM (Goldman and Arbeitman 2007; Dalton et al. 2013). Furthermore, we found that one member, dpr1, is important for courtship gating (Goldman and Arbeitman 2007). These proteins have been shown to interact with each other, and to mediate specificity in synaptic connectivity (Ozkan et al. 2013; Carrillo et al. 2015; Tan et al. 2015).

fru P1-expressing neurons have a large set of core genes expressed in both males and females and a striking ∼4 times more genes with male-biased abundance than female-biased. We further examined the data to determine if there were any systematic biases in the male or female TRAP libraries that could account for detecting more male-biased genes. For all TRAP libraries the 3′ most exon is 37% of exons. If we remove the 3′ most exon from the analyses, this does not change the finding of dramatically increased male-biased TRAP mRNA levels.

Examination of genes regulated by FruM and those with male-biased TRAP abundance

Of the 1210 genes that are significantly male-biased in the TRAP experiment, we investigated if these were potential targets of FruM, by examining the overlap between the 1210 genes identified in this experiment to the 1253 genes with transcripts identified as being regulated by at least one of three FruM isoforms, from our previous RNA-seq study (Dalton et al. 2013). In Dalton et al. (2013), each of three FruM isoforms was overexpressed in fru P1-expressing neurons, and tissue was collected from 16- to 24-hr-old adults, to facilitate the identification of genes regulated by FruM. Analysis of this data set was performed using the same mapping approaches to those used here, although the strain backgrounds are different. As this was an overexpression study, it is possible that FruM does not normally regulate some of the genes identified at the adult stage we examined. Furthermore, we do not expect every gene expressed in fru P1- expressing neurons to be a FruM target. We do find a significant overlap with 250 genes identified in the two studies (Table S7 and Table S8).

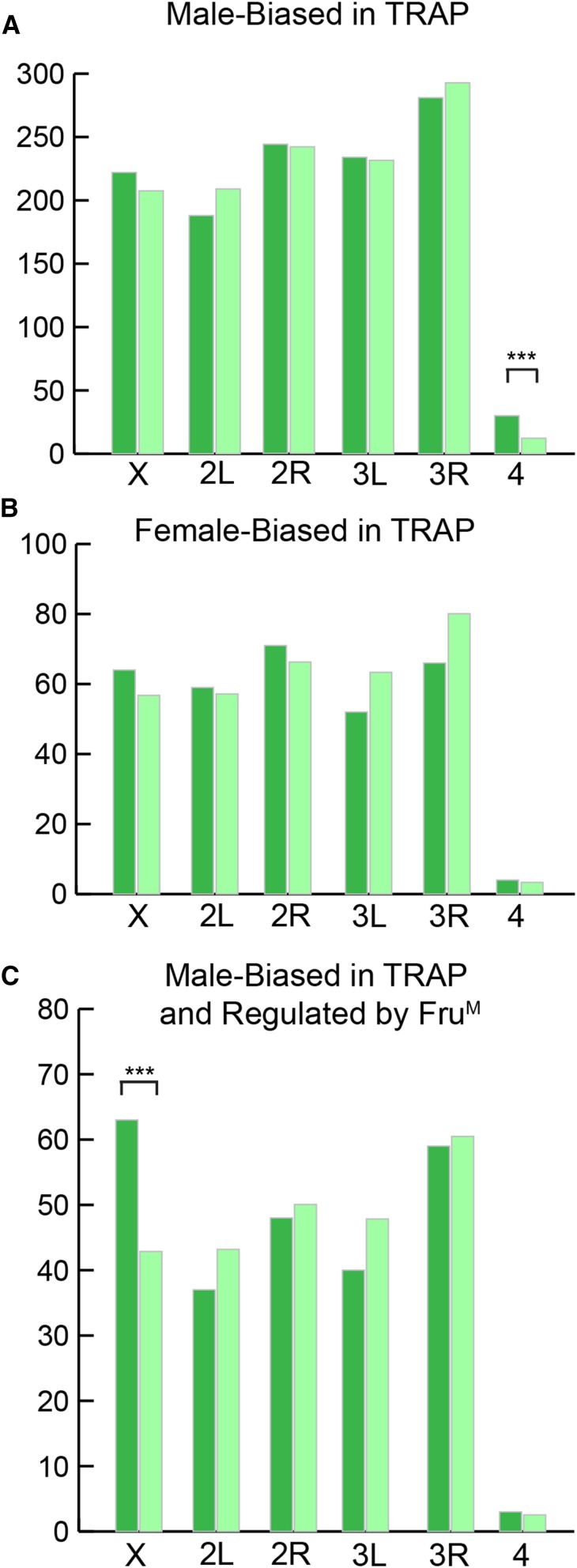

We also determined if there were significant differences in chromosome distribution for genes with male- and female-biased TRAP abundance, and found that genes with male-biased TRAP abundance were significantly enriched on the fourth chromosome; we found genes with sex-biased expression, and also those downstream of dsx highly significantly enriched on the fourth chromosome (Arbeitman et al. 2016). Furthermore, the 250 genes that have male-biased TRAP abundance, and were detected in our previous study as induced by FruM, are significantly enriched on the X chromosome (Figure 4 and Table S8), as are the larger set of 1253 genes regulated by FruM (Dalton et al. 2013). To assess if there is evidence for direct regulation of these 250 genes, and the set of 1210 genes with male-biased TRAP abundance, we analyzed the frequency of each FruM DNA binding site motif in these genes, and found significant enrichment for the binding sites of three FruM isoforms with known DNA binding motifs (p < 0.0001; Table 4 and Table S8) (Dalton et al. 2013). This suggests that these sets of genes include many that are likely directly regulated by FruM.

Figure 4.

Chromosome distribution of genes with biased TRAP expression. Chromosome distribution of the (A) 1210 genes identified with male-biased TRAP expression, (B) 331 genes identified with female-biased TRAP expression, and (C) 250 genes identified with male-biased TRAP expression and overlap with previously identified FruM regulated genes (Dalton et al. 2013). The observed (dark green bars) and expected (light green bars) gene counts for each chromosome are shown. *** p < 0.001 using a Fisher’s exact test.

Table 4. Enrichment of FruM DNA binding motifs.

| Total Genes | Number of Genes with Motif | Expected Number of Genes | Chi-Square Value | Degrees of Freedom | Likelihood Ratio Chi-Square | Fisher Raw p-Value (2-Tail) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genes with male-biased TRAP mRNAa | FruA DBD Motif | 1210 | 936 | 251.23 | 2782.216 | 1 | 2274.4412 | < 0.0001 |

| FruB DBD Motif | 1210 | 451 | 135.43 | 977.9614 | 1 | 731.1497 | < 0.0001 | |

| FruC DBD Motif | 1210 | 273 | 85.432 | 523.3722 | 1 | 385.0885 | < 0.0001 | |

| Genes with male-biased TRAP mRNAb | FruA DBD Motif | 250 | 234 | 51.908 | 832.5475 | 1 | 651.4013 | < 0.0001 |

| and regulated by FruM | FruB DBD Motif | 250 | 137 | 27.982 | 493.9181 | 1 | 298.8676 | < 0.0001 |

| FruC DBD Motif | 250 | 94 | 17.651 | 366.9582 | 1 | 202.3083 | < 0.0001 |

Genes with male-biased TRAP mRNA relative to female TRAP mRNA (Table 3).

Genes with male-biased TRAP mRNA relative to female TRAP mRNA (Table 3) and identified as regulated by FruM isoforms (Dalton et al. 2013).

Discussion

We have used cell-type-specific TRAP to identify the repertoires of Drosophila genes with actively translated mRNA products in male and female fru-P1-expressing neurons from heads of young adult flies. This allows us to gain insight into how two vastly different behaviors are directed by a largely shared set of fru P1-expressing neurons and from a shared genome. We find 1210 genes have male-biased TRAP abundance, which is ∼4 times more than the 331 genes with female-biased TRAP abundance. This asymmetry in sex-bias is unique relative to many other studies examining sex-biased gene expression, in that similar numbers of genes were discovered to have male- or female-biased mRNA abundance in somatic tissues (Arbeitman et al. 2004; Goldman and Arbeitman 2007; Lebo et al. 2009; Chang et al. 2011), although, we did see a large asymmetry in sex-biased gene expression with more male-biased gene expression (331 male; six female) in the developing third larval instar genital disc, using microarray analyses (Masly et al. 2011).

Consistent with previous studies, the number of genes with sex-biased expression in the whole head (input here) is similar between the two sexes in this study. The 1210 male-biased genes in the fru P1 mRNA translatome significantly overlap with genes that are regulated by FruM (250 genes overlap) (Dalton et al. 2013); the 250 genes common to both studies are also enriched on the X chromosome. Furthermore, the 1210 genes that have male-biased TRAP mRNA abundance are highly significantly enriched on the fourth chromosome; this is also true for genes with sex-biased expression and genes regulated by dsx in head tissues (Arbeitman et al. 2016). This is noteworthy, as the fourth chromosome in D. melanogaster evolved from an ancestral sex chromosome (Vicoso and Bachtrog 2013).

In our previous work examining head tissues, we found genes with male-biased expression are increased on the X chromosome and reside adjacent to dosage compensation machinery entry sites (Goldman and Arbeitman 2007; Chang et al. 2011), which was also observed separately (Catalan et al. 2012). Additionally, we found genes regulated by FruM to be enriched on the X chromosome (Dalton et al. 2013). We posited that this may be due to the unique properties of the X chromosome, which is less compacted and is also decorated with dosage compensation proteins in males. FruM function has evolved in the context of a male nucleus, and thus may have evolved biochemically to take advantage of the unique properties of the X chromosome in males. We further this idea, in light of our results presented here and previous work, by suggesting that the fourth chromosome also has unique properties for genes with sex-specific functions (Arbeitman et al. 2016).

There are several hypothesis about differences in the evolutionary properties of the X chromosome (reviewed in Vicoso and Charlesworth 2006), including the “faster-X” evolutionary hypothesis, which, in part, proposes that hemizygosity of the X chromosome in males could lead to more rapid adaptive fixation of male beneficial recessive alleles, as compared to autosomes (Rice 1984; Charlesworth et al. 1987). If targets of FruM are more likely to be on the X, the faster X may explain some of the male-bias in genes regulated by FruM identified here and previously. A gene’s residence on the X chromosome could allow for more rapid fixation of novel enhancer sequences that allow for FruM binding in males. Once these genes are under FruM regulation, selection could more rapidly act on X chromosome genes to retain new alleles/polymorphisms that are male beneficial, especially since regulation by FruM will have no impact in females.

We found that fru P1 neurons from males and females have a common repertoire of enriched, actively translated mRNAs (core genes) that is distinct from those identified using TRAP to detect mRNAs from all neurons in the adult head (see Thomas et al. 2012). While fru P1-expressing neurons in males and females underlie very different complex reproductive behaviors, there are aspects of both behaviors that may utilize similar molecular processes, which might be unique to the fru P1-expressing class of neurons (reviewed in Greenspan and Ferveur 2000; Griffith and Ejima 2009; Ferveur 2010; Dauwalder 2011). For example, both male and female reproductive behaviors are plastic and can be altered by adult experiences. Furthermore, reproductive behaviors in males and females require social interactions, and are coordinated with nutritional status, germline status, and circadian rhythms. The results presented here suggest that there is a common set of core genes that have products in the actively translated pool of mRNAs that may underlie the abilities of the neurons to coordinate these functions in both males and females.

The asymmetry in the number of genes with higher expression in male TRAP samples as compared to females (∼4 times more male-biased genes), and the relatively small number of genes with female-biased expression (331), suggests that the potential for female behaviors directed by fru P1-expressing neurons may largely be specified by the core set of genes. Female reproductive behaviors include subsets of behaviors found in both sexes, like rejection with wing flicks and running away, but also include behavioral subsets that are uniquely female, such as oviposition. It is possible we did not assay the critical fru P1-expressing neuronal populations, where transcripts important for specifying female-specific neuronal architecture and physiology are translated, such as neurons in the ventral nerve cord. Furthermore, it is known that there are fru P1 independent pathways that specify adult reproductive behaviors. There are DsxF+ neurons that do not overlap with fru P1-expressing neurons that may direct aspects of female-specific behaviors (Lee et al. 2002; Sanders and Arbeitman 2008; Rideout et al. 2010; Robinett et al. 2010). Both dsx and retained function in females to repress male behaviors, whereas in males dsx promotes and retained represses male behaviors (Ditch et al. 2005; Shirangi et al. 2006). Also, in the absence of fru P1, males can learn to perform courtship behavior in a dsx-dependent manner (Pan and Baker 2014), demonstrating that there are additional mechanisms to direct the potential for courtship behavior in males. Additional studies examining more time points and cell types are important to fully understand how sex differences in behaviors are built in both males and females, especially during developmental pupal stages, which has been shown to be a critical time for the specification of sexually dimorphic behaviors (Belote and Baker 1987; Arthur et al. 1998). Furthermore, it will be important to understand the endogenous physiological differences in male and female fru P1-expressing neurons, in light of the observation that activation of fru P1-expressing neurons in females induced performance of a male courtship sub-behavior: unilateral wing extension/vibration, though the song produced is structured differently than wild type male song (Clyne and Miesenbock 2008).

The results presented here may also provide mechanistic clues as to how a shared genome and shared fru P1-expressing neuronal substrates can give rise to two distinct behavioral outcomes. It is possible that FruM functions to promote male-specific behavior in the context of the same gene regulatory networks that underlie female behavior. This may be because the genetic specification of male and female behaviors is constrained at the molecular level, as genes are present in both males and females and share regulatory elements. This does not mean that female behaviors are simply the default state, as that would suggest too large of a constraint on the specification and evolution of female behaviors. We suggest that complexity in function and evolution of reproductive traits in both males and females can arise using molecular pathways that are activated in both male and female neurons. This is possible because evolutionary constraints differ between males and females, given that regulation by FruM can decouple the impact of novel regulation between the sexes.

If most genes that underlie the potential for female behaviors are also expressed in males, in fru P1-expressing neurons, selection on new alleles that favorably alter female behavioral traits will occur in both sexes. The new beneficial mutations that impact female behaviors are likely to have some phenotypic effects in both sexes, since based on our translatome study here, they are likely to be expressed in both males and females. However, constraint on evolution of female behaviors may be reduced if the specification of male behaviors is robust enough that perturbation in the pathways that direct female-behaviors have a small impact on male behaviors. To direct robust male behaviors, many genes could be recruited to be regulated by FruM, through addition of FruM binding sites, which will only have an impact in males. While there are elaborate male courtship displays, the evolution of the male behavioral process is constrained by female mate choice and the consequences on her fitness. Indeed, when male evolution continues in a context where female evolution is experimentally arrested, male fitness is increased and female fitness is decreased (Rice 1996,1998), given that selection on sexually antagonistic alleles has been removed.

Building a social behavior with a shared genome and a largely shared fru P1-expressing neuronal substrate may also limit the behavioral differences between males and females of a species. Thus, new alleles impacting sociality that benefit both males and females can be selected for in a shared genome. Further studies examining the evolution of FruM targets will inform on this question, especially focusing on X, fourth chromosome, and autosomal differences in evolution.

Conclusions

fru P1-expressing neurons have a unique, sex-nonspecific TRAP profile, compared to the TRAP profile of all neurons of the adult head, suggesting that these shared molecular properties underlie common reproductive behavioral needs. This core set of TRAP genes are significantly enriched with those that encode immunoglobulin domain-containing superfamily members. The fru P1-expressing neurons control very different sex-specific reproductive behaviors. These data suggest that additional expression/translation of genes in males plays a large role in the differences in the functions of these neurons between males and females. This suggests a model for a rewriting of the neuronal program where a baseline pattern is laid, largely setting up the potential for female-specific behaviors, and then information is overlaid to create the potential for male-specific behaviors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their laboratories for intellectual interactions and contributions. They also thank Rita Graze for comments and intellectual input on the manuscript. The authors are grateful for grant support and thank the agencies that funded the work. This work was supported by research funds from Florida State University (FSU) College of Medicine (M.A., J.D., and N.N.), and National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01GM073039 (PI is M.N.A.), GMS102227 (PI is L.M.M.), MH091561 (PI is S.V. Nuzhdin; M.N.A. and L.M.M. co-PIs). The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online at www.g3journal.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/g3.115.019265/-/DC1

Communicating editor: B. Oliver

Literature Cited

- Anand A., Villella A., Ryner L. C., Carlo T., Goodwin S. F., et al. , 2001. Molecular genetic dissection of the sex-specific and vital functions of the Drosophila sex determination gene fruitless. Genetics 158: 1569–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbeitman M. N., Fleming A. A., Siegal M. L., Null B. H., Baker B. S., 2004. A genomic analysis of Drosophila somatic sexual differentiation and its regulation. Development 131: 2007–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbeitman M. N., New F., Fear J. M., Howard T. S., Dalton J. D., et al. , 2016. Sex differences in Drosophila somatic gene expression: variation and regulation by doublesex. G3 (Bethesda) DOI: 10.1534/g3.116.027961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur B. I., Jr., Jallon J. M., Caflisch B., Choffat Y., Nothiger R., 1998. Sexual behaviour in Drosophila is irreversibly programmed during a critical period. Curr. Biol. 8: 1187–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attrill H., Falls K., Goodman J. L., Millburn G. H., Antonazzo G., et al. , 2016. FlyBase: establishing a Gene Group resource for Drosophila. Nucleic Acids Res. 44: D786–D792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T. L., Gribskov M., 1998. Combining evidence using p-values: application to sequence homology searches. Bioinformatics 14: 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beissbarth T., Speed T. P., 2004. GOstat: find statistically overrepresented gene ontologies within a group of genes. Bioinformatics 20: 1464–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belote J. M., Baker B. S., 1987. Sexual behavior: its genetic control during development and adulthood in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84: 8026–8030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y., 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate—a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 57: 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Cachero S., Ostrovsky A. D., Yu J. Y., Dickson B. J., Jefferis G. S., 2010. Sexual dimorphism in the fly brain. Curr. Biol. 20: 1589–1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo R. A., Ozkan E., Menon K. P., Nagarkar-Jaiswal S., Lee P. T., et al. , 2015. Control of synaptic connectivity by a network of Drosophila IgSF cell surface proteins. Cell 163: 1770–1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalan A., Hutter S., Parsch J., 2012. Population and sex differences in Drosophila brain gene expression. BMC Genomics 13: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang P. L., Dunham J. P., Nuzhdin S. V., Arbeitman M. N., 2011. Somatic sex-specific transcriptome differences in Drosophila revealed by whole transcriptome sequencing. BMC Genomics 12: 364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B., Coyne J. A., Barton N. H., 1987. The relative rates of evolution of sex-chromosomes and autosomes. Am. Nat. 130: 113–146. [Google Scholar]

- Chintapalli V. R., Wang J., Dow J. A. T., 2007. Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila models of human disease. Nat. Genet. 39: 715–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clyne J. D., Miesenbock G., 2008. Sex-specific control and tuning of the pattern generator for courtship song in Drosophila. Cell 133: 354–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton J. E., Lebo M. S., Sanders L. E., Sun F., Arbeitman M. N., 2009. Ecdysone receptor acts in fruitless-expressing neurons to mediate Drosophila courtship behaviors. Curr. Biol. 19: 1447–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton J. E., Fear J. M., Knott S., Baker B. S., McIntyre L. M., et al. , 2013. Male-specific Fruitless isoforms have different regulatory roles conferred by distinct zinc finger DNA binding domains. BMC Genomics 14: 659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S. R., Vasconcelos M. L., Ruta V., Luo S., Wong A., et al. , 2008. The Drosophila pheromone cVA activates a sexually dimorphic neural circuit. Nature 452: 473–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauwalder B., 2011. The roles of fruitless and doublesex in the control of male courtship. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 99: 87–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir E., Dickson B. J., 2005. fruitless splicing specifies male courtship behavior in Drosophila. Cell 121: 785–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson B. J., 2008. Wired for sex: the neurobiology of Drosophila mating decisions. Science 322: 904–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditch L. M., Shirangi T., Pitman J. L., Latham K. L., Finley K. D., et al. , 2005. Drosophila retained/dead ringer is necessary for neuronal pathfinding, female receptivity and repression of fruitless independent male courtship behaviors. Development 132: 155–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle J. P., Dougherty J. D., Heiman M., Schmidt E. F., Stevens T. R., et al. , 2008. Application of a translational profiling approach for the comparative analysis of CNS cell types. Cell 135: 749–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fear J. M., Arbeitman M. N., Salomon M. P., Dalton J. E., Tower J., et al. , 2015. The wright stuff: reimagining path analysis reveals novel components of the sex determination hierarchy in Drosophila. BMC Syst. Biol. 9: 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri S. L., Bohm R. A., Lincicome H. E., Hall J. C., Villella A., 2008. fruitless gene products truncated of their male-like qualities promote neural and behavioral maleness in Drosophila if these proteins are produced in the right places at the right times. J. Neurogenet. 22: 17–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferveur J. F., 2010. Drosophila female courtship and mating behaviors: sensory signals, genes, neural structures and evolution. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 20: 764–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley K. D., Edeen P. T., Foss M., Gross E., Ghbeish N., et al. , 1998. Dissatisfaction encodes a tailless-like nuclear receptor expressed in a subset of CNS neurons controlling Drosophila sexual behavior. Neuron 21: 1363–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith M. C., Hamada M., Horton P., 2010. Parameters for accurate genome alignment. BMC Bioinformatics 11: 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman T. D., Arbeitman M. N., 2007. Genomic and functional studies of Drosophila sex hierarchy regulated gene expression in adult head and nervous system tissues. PLoS Genet. 3: e216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graze R. M., Novelo L. L., Amin V., Fear J. M., Casella G., et al. , 2012. Allelic imbalance in Drosophila hybrid heads: exons, isoforms, and evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29: 1521–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan R. J., Ferveur J. F., 2000. Courtship in Drosophila. Annu. Rev. Genet. 34: 205–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith L. C., Ejima A., 2009. Courtship learning in Drosophila: diverse plasticity of a reproductive behavior. Learn. Mem. 16: 743–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasemeyer M., Yapici N., Heberlein U., Dickson B. J., 2009. Sensory neurons in the Drosophila genital tract regulate female reproductive behavior. Neuron 61: 511–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman M., Kulicke R., Fenster R. J., Greengard P., Heintz N., 2014. Cell type-specific mRNA purification by translating ribosome affinity purification (TRAP). Nat Protoc 9: 1282–1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman M., Schaefer A., Gong S., Peterson J. D., Day M., et al. , 2008. A translational profiling approach for the molecular characterization of CNS cell types. Cell 135: 738–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H., Fujitani K., Usui K., Shimizu-Nishikawa K., Tanaka S., et al. , 1996. Sexual orientation in Drosophila is altered by the satori mutation in the sex-determination gene fruitless that encodes a zinc finger protein with a BTB domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93: 9687–9692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H., Sato K., Koganezawa M., Ote M., Matsumoto K., et al. , 2012. Fruitless recruits two antagonistic chromatin factors to establish single-neuron sexual dimorphism. Cell 149: 1327–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K., Ote M., Tazawa T., Yamamoto D., 2005. Fruitless specifies sexually dimorphic neural circuitry in the Drosophila brain. Nature 438: 229–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K., Hachiya T., Koganezawa M., Tazawa T., Yamamoto D., 2008. Fruitless and doublesex coordinate to generate male-specific neurons that can initiate courtship. Neuron 59: 759–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King E. G., Macdonald S. J., Long A. D., 2012. Properties and power of the Drosophila synthetic population resource for the routine dissection of complex traits. Genetics 191: 935–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl J., Ostrovsky A. D., Frechter S., Jefferis G. S., 2013. A bidirectional circuit switch reroutes pheromone signals in male and female brains. Cell 155: 1610–1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvitsiani D., Dickson B. J., 2006. Shared neural circuitry for female and male sexual behaviours in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 16: R355–R356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Trapnell C., Pop M., Salzberg S. L., 2009. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10: R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law C. W., Chen Y. S., Shi W., Smyth G. K., 2014. voom: precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol. 15: R29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebo M. S., Sanders L. E., Sun F., Arbeitman M. N., 2009. Somatic, germline and sex hierarchy regulated gene expression during Drosophila metamorphosis. BMC Genomics 10: 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G., Foss M., Goodwin S. F., Carlo T., Taylor B. J., et al. , 2000. Spatial, temporal, and sexually dimorphic expression patterns of the fruitless gene in the Drosophila central nervous system. J. Neurobiol. 43: 404–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G., Villella A., Taylor B. J., Hall J. C., 2001. New reproductive anomalies in fruitless-mutant Drosophila males: extreme lengthening of mating durations and infertility correlated with defective serotonergic innervation of reproductive organs. J. Neurobiol. 47: 121–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G., Hall J. C., Park J. H., 2002. Doublesex gene expression in the central nervous system of Drosophila. J. Neurogenet. 16: 229–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Zhou J., White K. P., 2014. RNA-seq differential expression studies: more sequence or more replication? Bioinformatics 30: 301–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyne R., Smith R., Rutherford K., Wakeling M., Varley A., et al. , 2007. FlyMine: an integrated database for Drosophila and Anopheles genomics. Genome Biol. 8: R129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoli D. S., Foss M., Villella A., Taylor B. J., Hall J. C., et al. , 2005. Male-specific fruitless specifies the neural substrates of Drosophila courtship behaviour. Nature 436: 395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoli D. S., Meissner G. W., Baker B. S., 2006. Blueprints for behavior: genetic specification of neural circuitry for innate behaviors. Trends Neurosci. 29: 444–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masly J. P., Dalton J. E., Srivastava S., Chen L., Arbeitman M. N., 2011. The genetic basis of rapidly evolving male genital morphology in Drosophila. Genetics 189: 357–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre L. M., Bono L. M., Genissel A., Westerman R., Junk D., et al. , 2006. Sex-specific expression of alternative transcripts in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 7: R79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A., Williams B. A., Mccue K., Schaeffer L., Wold B., 2008. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods 5: 621–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan E., Carrillo R. A., Eastman C. L., Weiszmann R., Waghray D., et al. , 2013. An extracellular interactome of immunoglobulin and LRR proteins reveals receptor-ligand networks. Cell 154: 228–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y., Baker B. S., 2014. Genetic identification and separation of innate and experience-dependent courtship behaviors in Drosophila. Cell 156: 236–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice W. R., 1984. Sex-chromosomes and the evolution of sexual dimorphism. Evolution 38: 735–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice W. R., 1996. Sexually antagonistic male adaptation triggered by experimental arrest of female evolution. Nature 381: 232–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice W. R., 1998. Male fitness increases when females are eliminated from gene pool: Implications for the Y chromosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 6217–6221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout E. J., Billeter J. C., Goodwin S. F., 2007. The sex-determination genes fruitless and doublesex specify a neural substrate required for courtship song. Curr. Biol. 17: 1473–1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout E. J., Dornan A. J., Neville M. C., Eadie S., Goodwin S. F., 2010. Control of sexual differentiation and behavior by the doublesex gene in Drosophila. Nat. Neurosci. 13: 458–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinett C. C., Vaughan A. G., Knapp J. M., Baker B. S., 2010. Sex and the single cell. II. There is a time and place for sex. PLoS Biol. 8: e1000365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S. W., Herzyk P., Dow J. A. T., Leader D. P., 2013. FlyAtlas: database of gene expression in the tissues of Drosophila. Nucleic Acids Res. 41: D744–D750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryner L. C., Goodwin S. F., Castrillon D. H., Anand A., Villella A., et al. , 1996. Control of male sexual behavior and sexual orientation in Drosophila by the fruitless gene. Cell 87: 1079–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders L. E., Arbeitman M. N., 2008. Doublesex establishes sexual dimorphism in the Drosophila central nervous system in an isoform-dependent manner by directing cell number. Dev. Biol. 320: 378–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirangi T. R., Taylor B. J., McKeown M., 2006. A double-switch system regulates male courtship behavior in male and female Drosophila. Nat. Genet. 38: 1435–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siwicki K. K., Kravitz E. A., 2009. Fruitless, doublesex and the genetics of social behavior in Drosophila. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 19: 200–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockinger P., Kvitsiani D., Rotkopf S., Tirian L., Dickson B. J., 2005. Neural circuitry that governs Drosophila male courtship behavior. Cell 121: 795–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallafuss A., Washbourne P., Postlethwait J., 2014. Temporally and spatially restricted gene expression profiling. Curr. Genomics 15: 278–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L., Zhang K. X., Pecot M. Y., Nagarkar-Jaiswal S., Lee P. T., et al. , 2015. Ig superfamily ligand and receptor pairs expressed in synaptic partners in Drosophila. Cell 163: 1756–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telonis-Scott M., Kopp A., Wayne M. L., Nuzhdin S. V., McIntyre L. M., 2009. Sex-specific splicing in Drosophila: widespread occurrence, tissue specificity and evolutionary conservation. Genetics 181: 421–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A., Lee P. J., Dalton J. E., Nomie K. J., Stoica L., et al. , 2012. A versatile method for cell-specific profiling of translated mRNAs in Drosophila. PLoS One 7: e40276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran D. H., Meissner G. W., French R. L., Baker B. S., 2014. A small subset of fruitless subesophageal neurons modulate early courtship in Drosophila. PLoS One 9: e95472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui-Aoki K., Ito H., Ui-Tei K., Takahashi K., Lukacsovich T., et al. , 2000. Formation of the male-specific muscle in female Drosophila by ectopic fruitless expression. Nat. Cell Biol. 2: 500–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicoso B., Charlesworth B., 2006. Evolution on the X chromosome: unusual patterns and processes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 7: 645–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicoso B., Bachtrog D., 2013. Reversal of an ancient sex chromosome to an autosome in Drosophila. Nature 499: 332–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villella A., Hall J. C., 2008. Neurogenetics of courtship and mating in Drosophila. Adv. Genet. 62: 67–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villella A., Gailey D. A., Berwald B., Ohshima S., Barnes P. T., et al. , 1997. Extended reproductive roles of the fruitless gene in Drosophila revealed by behavioral analysis of new fru mutants. Genetics 147: 1107–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Philipsborn A. C., Liu T., Yu J. Y., Masser C., Bidaye S. S., et al. , 2011. Neuronal control of Drosophila courtship song. Neuron 69: 509–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto D., 2007. The neural and genetic substrates of sexual behavior in Drosophila. Adv. Genet. 59: 39–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto D., Koganezawa M., 2013. Genes and circuits of courtship behaviour in Drosophila males. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14: 681–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C. H., Rumpf S., Xiang Y., Gordon M. D., Song W., et al. , 2009. Control of the postmating behavioral switch in Drosophila females by internal sensory neurons. Neuron 61: 519–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yapici N., Kim Y. J., Ribeiro C., Dickson B. J., 2008. A receptor that mediates the post-mating switch in Drosophila reproductive behaviour. Nature 451: 33–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J. Y., Kanai M. I., Demir E., Jefferis G. S., Dickson B. J., 2010. Cellular organization of the neural circuit that drives Drosophila courtship behavior. Curr. Biol. 20: 1602–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C., Franconville R., Vaughan A. G., Robinett C. C., Jayaraman V., et al. , 2015. Central neural circuitry mediating courtship song perception in male Drosophila. eLife 4: 08477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The accession number for the data is: GSE67743 at the Gene Expression Omnibus.