Abstract

Glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), a multifunctional serine/threonine kinase found in all eukaryotes, had been initially identified as a key regulator of insulin-dependent glycogen synthesis. It is now known that GSK3β functions in diverse cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, motility and survival. Aberrant regulation of GSK3β has been implicated in a range of human pathologies including non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, some neurodegenerative diseases, and bipolar disorder. As a consequence, the therapeutic potential of GSK3β inhibitors has become an important area of investigation. However, GSK3β also participates in neoplastic transformation and tumor development. The role of GSK3β in tumorigenesis and cancer progression remains controversial; it may function as a “tumor suppressor” for certain types of tumors, but promotes growth and development for some others. GSK3β also mediates drug sensitivity/resistance in cancer chemotherapy. Therefore, although GSK3β is an attractive therapeutic target for a number of human diseases, its potential impact on tumorigenesis and cancer chemotherapy needs to be carefully evaluated. This mini-review discusses the role of GSK3β in tumorigenesis/cancer progression as well as its modulation of cancer chemotherapy.

Keywords: Apoptosis, carcinogenesis, cell cycle, chemotherapy, neoplastic transformation

Introduction

Glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) has become one of the most attractive therapeutic targets for the treatment of diabetes, inflammation, and multiple neurological diseases, including Alzheimer’s, stroke and bipolar disorders [1,2]. GSK3 is a multifunctional serine/threonine kinase, originally found in mammals, and homologues have been found in all eukaryotes [3,4]. GSK3 was first identified as a critical mediator in glycogen metabolism and insulin signaling. It is now known that GSK3 is an important component of diverse signaling pathways involved in the regulation of cell fate, protein synthesis, glycogen metabolism, cell mobility, proliferation and survival [3,4]. There are two mammalian GSK3 isoforms encoded by distinct genes: GSK3α and GSK3β. The α and β isoforms share 85% identity [3]. The two genes map to human chromosomes 19q13.2 (GSK3α) and 3q13.3 (GSK3β). An elegant historical synopsis of the cloning and characterization of GSK3 genes has been reviewed by Plyte et al. [5]. Despite a high degree of similarity and functional overlap, these isoforms are not functionally identical and redundant. The signaling pathway and protein function of GSK3β are much better investigated. This review will focus on the action of GSK3β. Due to its diverse cellular functions, the pathways in which GSK3β acts as a key regulator, when dysregulated, have been implicated in the development of a number of human diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, some neurodegenerative diseases and bipolar disorder [3,4,6]. The dysregulation of GSK3β has also been implicated in tumorigenesis and cancer progression [7–10]. However, the mechanisms underlying GSK3β regulation of neoplastic transformation and tumor development are unclear; it remains controversial whether GSK3β is a “tumor suppressor” or “tumor promoter.” This review will discuss the evidence that supports GSK3β as both “tumor suppressor” and “tumor promoter,” and the underlying mechanisms. In addition, the role of GSK3β in cancer chemotherapy will be briefly reviewed.

1. Regulation of GSK3β and its substrates

Unlike most protein kinases, GSK3β is constitutively active in resting cells and undergoes a rapid and transient inhibition in response to a number of external signals [3,4]. GSK3β activity is regulated by site-specific phosphorylation. Full activity of GSK3β generally requires phosphorylation at tyrosine (Tyr216), and conversely, phosphorylation at serine (Ser9) inhibits GSK3β activity. GSK3β is subjected to multiple regulatory mechanisms and phosphorylation of Ser9 is probably the most important regulatory mechanism. Several kinases are capable of mediating this modification, including p70 S6 kinase, extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs), p90Rsk (also called MAPKAP kinase-1), protein kinase B (also called Akt), certain isoforms of protein kinase C (PKC), and cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase (protein kinase A) [3,4]. In opposition to the inhibitory modulation of GSK3β that occurs by serine phosphorylation, tyrosine phosphorylation of GSK3β increases the enzyme’s activity. Studies of tyrosine phosphorylation of GSK3β are relatively sparse and information about this regulatory mechanism is fragmentary. Stimulation of pGSK3β(Tyr216) is reported to be mediated by alterations in intracellular calcium levels and a calcium-dependent tyrosine kinase, proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (PYK2), or by Fyn, a member of the Src tyrosine family [11–13]. pGSK3β(Tyr216) is also subject to the regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK1/2) [14].

Although phosphorylation of GSK3β is the most widely studied mechanism of regulation, a recent study indicated GSK3β can be activated without apparent changes in pGSK3β(Tyr216) and pGSK3β(Ser9) [15]. Protein complex formation and intracellular localization also have important regulatory influences on GSK3β activity. Such complex regulatory mechanisms are necessary for an enzyme that modifies multiple and diverse substrates, including metabolic, signaling, and structural proteins and transcription factors. These regulatory mechanisms have been elegantly reviewed [3,4].

GSK3β is active in resting cells and is inactivated during cellular responses. Its substrates therefore tend to be dephosphorylated; most of these substrates are functionally inhibited by GSK3β. GSK3β appears to act as a general repressor, keeping its targets switched off or inaccessible under resting conditions. More than 40 proteins are substrates of GSK3β, and these proteins have roles in a wide spectrum of cellular processes, including glycogen metabolism, transcription, translation, cytoskeletal regulation, cell differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis [4,8]. A number of substrates that have a close association with tumorigenesis and cancer development are briefly discussed here. One of the most well-known substrates of GSK3β is β-catenin, and GSK3β is an important regulator of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. The Wnts are a family of secreted, cysteine-rich and glycosylated protein ligands. Wnt signal transduction ultimately results in the activation of genes regulated by the T-cell factor (TCF)/lymphoid enhancer factor (LEF) family of transcription factors and is implicated in tumorigenesis and malignancy [16]. In the absence of Wnt signals, free cytoplasmic β-catenin is incorporated into a cytoplasmic complex that includes Axin, GSK3β and adenmatous polyposis coli (APC). This enables GSK3β to phosphorylate β-catenin and results in ubiquitin-mediated degradation of β-catenin. Wnt signaling inactivates GSK3β and prevents it from phosphorylating β-catenin, thus stabilizing β-catenin in the cytoplasm. As β-catenin accumulates, it translocates into the nucleus where it binds to TCF/LEF and dramatically increases their transcriptional activity. Genes up-regulated by TCF/LEF include proto-oncogenes, such as c-myc and cyclin-D1, and genes regulating cell invasion/migration, such as MMP-7.

In addition to β-catenin, many proto-oncogenic or tumor suppressing transcription and translation factors are substrates of GSK3β. For example, tumor suppressor transcription factor p53 is a target of GSK3β. GSK3β regulates the levels as well as intracellular localization of p53 [6]. GSK3β forms a complex with nuclear p53 to promote p53-induced apoptosis. GSK3β directly modulates the activity of transcription factors, activator protein 1 (AP-1) and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) [4,8,9]. Both transcription factors play a critical role in neoplastic transformation and tumor development.

2. Involvement of GSK3β in tumorigenesis and cancer progression

Since GSK3β negatively regulates many proto-oncogenic proteins and cell cycle regulators, one would predict that GSK3β may suppress tumorigenesis. Several studies indeed support that GSK3β functions as a “tumor suppressor” and represses cellular neoplastic transformation and tumor development. GSK3β has been reported to be a negative regulator of skin tumorigenesis. In a mouse epidermal multistage carcinogenesis model, a dramatic increase in pGSK3β(Ser9) (inactive form of GSK3β) is observed in late papillomas and squamous cell carcinomas, while a significant decrease in pGSK3β(Tyr216) (active form of GSK3β) is detected in squamous cell carcinoma samples compared to normal tissues; this indicates an inactivation of GSK3β occurs during mouse skin carcinogenesis [17]. A recent study examining human skin cancer tissues reveals a strong pGSK3β(Ser9) expression in squamous cell carcinoma cells [18].

We have observed a dramatic decrease of GSK3β expression in human non-melanoma skin cancers (cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas and basal cell carcinomas) compared to adjacent normal keratinocytes [19]. In addition, the immunostaining for GSK3β in keratinocytes of patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas or basal cell carcinomas is generally weaker than keratinocytes of age and sex-matched normal subjects. The expression of pGSK3β(Tyr216) in skin specimens of cancer patients and control subjects is negative. The tumor suppressive effect of GSK3β is further established using an in vitro model of neoplastic transformation, mouse epidermal JB6 P+ cells. In response to epidermal growth factor (EGF) or 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA), the promotion sensitive JB6 P+ cells initiate neoplastic transformation, whereas the promotion resistant JB6 P− cells do not. Consistent with the observations in human skin tissues, the expression levels of GSK3β in JB6 cells are correlated to the stage or potential of cell transformation. Transformation-resistant JB6 P− cells express the highest levels of GSK3β while the levels of GSK3β in transformation-sensitive JB6 P+ cells are intermediate; on the other hand, JB7 cells, the transformed derivatives of JB6, have the least amount of GSK3β [19]. Tumor promoters EGF and TPA inactivate GSK3β by inducing strong phosphorylation of GSK3β at Ser9 in transformation-sensitive JB6 P+ cells. Transformation-resistant JB6 P− cells are insensitive to this negative regulation of GSK3β. The involvement of GSK3β in skin tumorigenesis is further demonstrated by modulation of GSK3β activity in JB6 P+ cells. Overexpression of wild type GSK3β or constitutively active S9A mutant GSK3β inhibits in vitro cell transformation, as well as in vivo tumorigenicity in nude mice. In contrast, overexpression of a kinase deficient K85R GSK3β or treatment with GSK3β inhibitors drastically promotes in vitro cell transformation and greatly enhances in vivo tumorigenicity. Together, these results indicate that GSK3β participates in neoplastic transformation and tumor development during skin carcinogenesis, and down-regulation or inactivation of GSK3β is oncogenic for epidermal cells.

The negative regulation of GSK3β on tumorigenesis also appears true for mammary tumors. Farago et al. [20] show that antagonizing the endogenous activity of GSK3β by tissue-specific expression of a kinase-inactive GSK3β (dominant negative) in mouse mammary glands promotes mammary tumorigenesis. The promotion of mammary tumorigenesis by this kinase-inactive GSK3β is accompanied by the accumulation of β-catenin and cyclin D1, suggesting that the promotion is mediated by the dysregulation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Conversely, activation of GSK3β suppresses mammary tumorigenesis. Activation of GSK3β by adiponectin induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in MDAMB-231 human breast cancer cells, which is accompanied by suppressed intracellular accumulation of β-catenin and its nuclear activities and reduced cyclin D1 levels [21]. Moreover, in vivo activation of GSK3β by supplementation of recombinant adiponectin or adenovirus-mediated overexpression of adiponectin substantially reduces the mammary tumorigenicity of MDAMB-231 cells in nude mice [21]. Similarly, activation of GSK3β by rapamycin also induces down-regulation of cyclin D1 expression, cell cycle arrest and the inhibition of anchorage-dependent growth in breast cancer cells [22]. Consistent with these findings, expression of constitutively active GSK3β (S9A mutant) causes apoptosis of human breast cancer cells; moreover, injection of the liposome complex with GSK3β to tumor-bearing mice significantly inhibits mammary tumor growth [23]. Taken together, GSK3β may function as a “tumor suppressor” for mammary tumors, whereas antagonism of GSK3β activity is oncogenic for mammary epithelial cells.

In addition to participation in neoplastic transformation and tumor growth, GSK3β is also proposed to be involved in cancer cell metastasis [24,25]. The increased motility and invasiveness of cancer cells in the first phase of metastasis are reminiscent of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) during embryonic development [24–26]. Epithelial cells usually exist as sheets of immotile, tightly packed, well-coupled, polarized cells with distinct apical, basal and lateral surfaces. These cells can dramatically alter their morphology to become motile, fibroblast-like mesenchymal cells in EMT. The essential features of EMT are the disruption of intercellular contacts and the enhancement of cell motility, thereby leading to the release of cells from the parent epithelial tissue. The resulting mesenchymal-like phenotype is suitable for migration and, thus, for tumor invasion and dissemination, allowing metastatic progression to proceed [25,26]. GSK3β plays an important role in EMT most likely through the modulation of Wnt, Hedgehog and Snail (a zinc-finger transcriptional repressor) pathways; inhibition of GSK3β promotes the development of EMT [24–26]. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) has been the best documented in the regulation of various aspects of tumor progression and metastasis. COX-2 is an independent prognostic factor in gastric cancer. Inhibition of GSK3β stimulates COX-2 expression in gastric cancer cells through increasing COX-2 mRNA stability [27], indicating GSK3β is a negative regulator of COX-2. GSK3β regulation of COX-2 in tumor cells may affect tumor development and metastasis.

In contrast to its tumor suppressive role, some studies suggest that GSK3β may actually promote tumorigenesis and cancer development. GSK3β protein overexpression has been found in human ovarian, colon and pancreatic carcinomas [9]. Higher levels of GSK3β are observed in liver tumors than in normal liver tissues in a mouse model of hepatic carcinogenesis [28]. Consistent with its high expression in ovarian tumors, GSK3β is reported to positively regulate the proliferation and survival of human ovarian cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo [29]. Inhibition of GSK3β activity by pharmacological inhibitors suppresses proliferation of the ovarian cancer cells in vitro and prevents the formation of tumors in nude mice generated by the inoculation of human ovarian cancer cells. Conversely, overexpressing a constitutively active form of GSK3β increases cyclin D1 expression and induces cell cycle progression of ovarian cancer cells [29].

Levels of GSK3β expression and amounts of its active form in colon cancer cell lines and colorectal cancer patients are higher than in their normal counterparts [2,30]. Depletion of GSK3β by RNA interference or pharmacological inhibition of GSK3β kinase activity results in decreased survival and proliferation of colon cancer cells in vitro and in vivo [30,31]. Higher expression of active GSK3β is also observed in pancreatic cancer cells [32]. Nuclear accumulation of active GSK3β is found in some pancreatic cancer cell lines and human pancreatic adenocarcinomas [33]. GSK3β nuclear accumulation is significantly correlated with human pancreatic cancer dedifferentiation. Inhibition of GSK3β decreases pancreatic cancer cell survival and proliferation, and arrests pancreatic tumor growth in established tumor xenografts [32,33]. Other studies indicate that GSK3β activation enhances the proliferation and survival of hepatocellular, prostate and lymphocytic leukemia cancer cells [34–37]. Additionally, inactivation of GSK3β is associated with growth suppression in medullary thyroid cancer cells [38]. Therefore, GSK3β may be a “tumor promoter” for certain types of tumors. For this reason, inhibition of GSK3β has been proposed to be an attractive therapeutic approach for the treatment of colon and pancreatic cancers [9,39].

3. Involvement of GSK3β in cancer chemotherapy

GSK3β also regulates cellular sensitivity/resistance to cancer chemotherapy. Increased expression of pGSK3β(Ser9) is observed in cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer cell line (CP70) compared to its cisplatin-sensitive counterpart A2780 cells [40]. High pGSK3β(Ser9) levels in CP70 cells suggest that suppressed GSK3β activity may account for their resistance to cisplatin. Inhibition of GSK3β by treatment with lithium significantly reduces cisplatin-induced apoptosis and raises the IC50 of cisplatin for ovarian cancer cells. Conversely, reactivation of GSK3β by expressing a constitutively active S9A GSK3β mutant reverses cisplatin resistance and enhances sensitivity of ovarian cancer cells to cisplatin. Thus, GSK3β inhibition may confer resistance to cisplatin in ovarian carcinomas. Similarly, treatment with lithium causes resistance of hepatoma cells to two chemotherapy drugs, etoposide and camptothecin [41]. GSK3β reactivation by exogenous expression of S9A GSK3β mutant or treatment with LY294002 sensitizes hepatoma cells to etoposide- and camptothecin-induced apoptosis [42].

Rapamycin is known to activate GSK3β; it enhances a chemotherapy drug paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in GSK3β wild-type, but not in GSK3β null breast cancer cells [22], indicating that GSK3β mediates rapamycin-induced chemosensitivity. A similar report indicates that GSK3β activation sensitizes human breast cancer cells to chemotherapy drugs, 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, taxol or prodigiosin-induced apoptosis [23,43]. Overexpression/activation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and its receptor TrkB in neuroblastoma tumors are associated with poor prognosis and resistance to chemotherapy. TrkB activation-induced resistance to chemotherapy is mediated via GSK3β [44]. Treatment of neuroblastoma cells with inhibitors of GSK3β or a GSK3β-targeted small interfering RNA enhances resistance to chemotherapy drugs. Conversely, expression of a constitutively active S9A GSK3β sensitizes neuroblastoma cells to chemotherapy agents [44]. However, in some cases, inhibition of GSK3β may sensitize cells to chemotherapy; small-molecule GSK3β inhibitor promotes a genotoxic agent, adriamycin-induced apoptosis in human colorectal cancer cells in a p53-dependent manner [45].

In summary, it appears that GSK3β regulation of response or resistance to cancer chemotherapy is also tumor cell type-dependent. The GSK3β-regulated differential responses to chemotherapy among tumor cell types, however, are not entirely consistent with its role as a tumor suppressor or tumor promoter. For example, GSK3β functions as a tumor suppressor for mammary tumors; its activation sensitizes human breast cancer cells to chemotherapy drugs. On the other hand, GSK3β acts as a tumor promoter for colon tumors and its inhibition enhances the response of colon cancer cells to chemotherapy. In ovarian tumors, however, the finding that GSK3β inhibition confers resistance to cisplatin contradicts its tumor promoting role. Therefore, it is likely the mechanisms underlying GSK3β regulation of tumorigenesis and drug response are different.

4. The mechanisms of GSK3β action

Since GSK3β regulates diverse substrates and signaling pathways, the mechanisms underlying its anti-tumor or pro-tumor action are complex. One of the most important impacts of GSK3β on neoplastic transformation tumor development is likely mediated by its influence on Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Phosphorylation of β-catenin by active GSK3β targets β-catenin for ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation and maintains a low level of cytoplasmic β-catenin. Activation of Wnt signaling inhibits GSK3β and stabilizes cytoplasmic β-catenin, qualifying β-catenin as a proto-oncogene [46,47]. As β-catenin accumulates, it translocates into the nucleus where it binds to TCF and LEF transcription factors and increases their transcriptional activity. A number of TCF/LEF-targeted proto-oncogenes, such as c-myc and cyclin-D1, and genes involved in cell invasion/migration, such as MMP-7, are drastically up-regulated. In a mouse model of mammary tumorigenesis, inhibition of GSK3β by overexpression of kinase-inactive GSK3β in mouse mammary glands promotes mammary tumorigenesis; this is accompanied by the over-expression of β-catenin and cyclin D1 [20], supporting that GSK3β inhibition causes dysregulation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway which results in tumor promotion. However, other evidence indicates that GSK3β’s action is independent of perturbance of β-catenin. Hoeflich et al. [48] report that cyclin D1 levels and β-catenin accumulation are not perturbed in GSK3β deficient mice. In colon cancer, where β-catenin dysregulation is involved in the pathogenesis of the tumor, GSK3β remains active and is overexpressed in the cancer cells; active GSK3β is required for the growth of colon cancer cells [9]. These findings suggest GSK3β may also modulate tumor development through mechanisms other than Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

Recent studies suggest that GSK3β-induced suppression of mammary tumors is mediated by myeloid cell leukemia-1 (Mcl-1), an anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member. Mcl-1 is overexpressed in many types of human cancer and associates with cell immortalization, malignant transformation and chemoresistance. The expression of Mcl-1 is correlated with pGSK3β(Ser9) (inactive form of GSK3β) in multiple cancer cell lines and primary human cancer samples; the high level of Mcl-1 is related to high tumor grade and poor survival of breast cancer patients [18]. Activation of GSK3β results in Mcl-1 degradation, while inactivation of GSK3β causes accumulation of Mcl-1 [23]. More importantly, inactivation of GSK3β promotes mammary tumor development and induces chemoresistance in a Mcl-1-dependent manner [18,23].

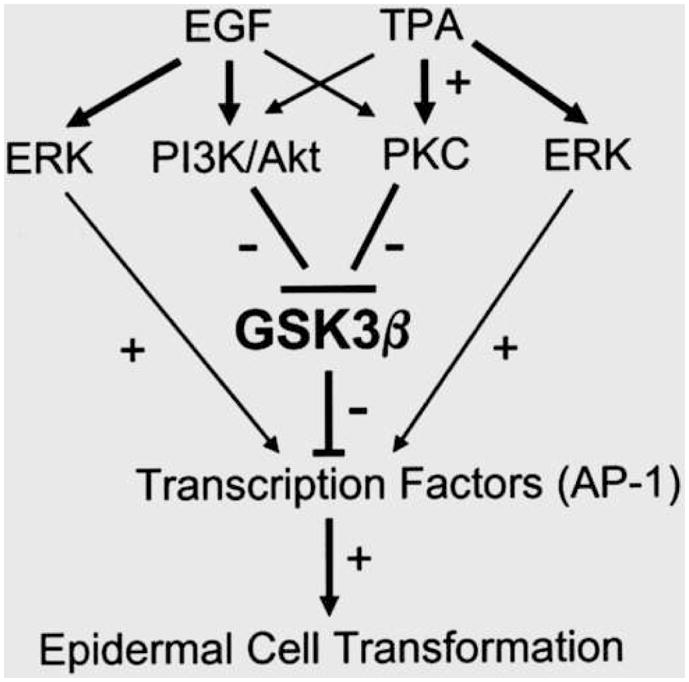

GSK3β is a direct regulator of AP-1. AP-1 is a heterodimeric transcription factor complex composed of a Jun family member and a FOS family member that binds the TRE DNA sequence (5′-TGAGTCA-3′). It is involved in a variety of cellular processes, including growth, survival and tumorigenesis [49]. GSK3β-induced c-Jun phosphorylation inhibits DNA binding activity and suppresses AP-1 activity [4]. AP-1 activation is required for the transformation of epidermal cells and skin carcinogenesis [50,51]. In an in vitro model of epidermal cell neoplastic transformation, activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), PKC or ERK results in AP-1 activation and subsequent neoplastic transformation [52,53]. We demonstrate that activation of PI3K and PKC inhibits GSK3β activity by stimulating pGSK3β(Ser9) [19]. Inactivation of GSK3β drastically enhances AP-1 activity and promotes epidermal cell transformation (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Diagram of the role of GSK3β in skin tumorigenesis. EGF and TPA activate PI3K/Akt and PKC signaling pathways which induce phosphorylation of GSK3β(Ser9) and inactivate GSK3β. Inactivation of GSK3β stimulates oncogenic transcription factor AP-1. Hyperactivity of AP-1 promotes skin tumorigenesis. EGF and TPA can also activate AP-1 through the MEK1/ERK pathway which is independent of GSK3β.

NF-κB is a transcription factor that plays a crucial role in many physiological and patho-physiological processes, including control of the adaptive and innate immune responses, inflammation, cell proliferation, survival and differentiation [54,55]. In a resting state, NF-κB, p65/p50 heterodimers are generally inactive and form a complex with its inhibitory proteins IκBα in the cytoplasm. Activation of IκB kinase (IKK) phosphorylates IκBα and results in its proteasomal degradation; this leads to liberation and translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus where it regulates gene expression. A role for NF-κB as a tumor promoter is firmly established. However, recent findings suggest an inhibitory role for NF-κB in carcinogenesis and tumorigenesis [54,55]. NF-κB activity is subject to regulation of GSK3β; the regulation is either positive or negative depending on the cell types being investigated [4,7]. In colon and pancreatic cancer cells, GSK3β positively regulates NF-κB and inactivation of GSK3β inhibits NF-κB activity [9]. GSK3β-induced increase in the growth of colon and pancreatic cancer cells is believed to be mediated by NF-κB activation [7,9]. However, GSK3β is reported to inhibit NF-κB activity in neuronal cells and astrocytes [56–58]. The molecular mechanisms underlying GSK3β/NF-κB interaction remain to be further investigated. In addition to AP-1 and NF-κB, several other transcription factors that may participate in the regulation of cell proliferation, survival and tumorigenesis are subject to regulation of GSK3β; these include cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB), p53, heat shock factor-1 (HSF-1) and nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) [4,6].

The tumor promoting or suppressing effect of GSK3β may be mediated by its modulation cell cycle and cell survival. In general, GSK3β activation could cause cell cycle arrest by suppressing the expression of a number of critical cell cycle regulators, such as cyclin D1, cyclin E, c-Jun and c-Myc; these regulators are closely associated with cell transformation and tumor development [59].

GSK3β is also an important regulator of cell survival, and activation of GSK3β can be either anti-apoptotic or pro-apoptotic. It has been suggested that GSK3β promotes cell death caused by the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, but inhibits the death receptor-mediated extrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway [6]. The intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway causes the disruption of mitochondria, leading to cell destruction. The intrinsic apoptotic signaling cascade can be induced by numerous stimuli that cause cell damage, such as DNA damage, oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress; GSK3β promotes this cascade by facilitating signals that cause disruption of mitochondria and by regulating transcription factors that control the expression of anti- or pro-apoptotic proteins.

The extrinsic apoptotic pathway, on the other hand, is mediated by the activation of cell-surface death domain-containing receptors (DRs) and initiates apoptosis by activating caspase-8 [6]. DRs belong to the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family of receptors that contain conserved intracellular death domains that are critical for the initiation of extrinsic apoptotic signaling. Among the most well known death receptors are TNF receptor 1 (TNF-R1), Fas, death receptor 4 (DR4) and DR5. GSK3β activation generally inhibits the extrinsic apoptotic pathway. Conversely, death receptor-induced extrinsic apoptotic signaling is potentiated by GSK3β inhibition caused by the treatment of lithium and other GSK3β inhibitors [6]; these may be useful in cancer therapies in conjunction with agents that activate death receptors, for example, employing GSK3β inhibitors in combination with the DR4/DR5 activating ligand TRAIL may be efficient in killing tumor cells since these death receptors are preferentially expressed in cancer cells.

Conclusion

GSK3β has emerged as one of the most attractive therapeutic targets for the treatment of some neurological diseases, including Alzheimer’s, stroke and bipolar disorders, as well as diabetes and inflammation. Recently, GSK3β has been viewed as a viable target in the treatment of several human neoplasms due to its involvement in tumor development and chemoresistance. However, it remains controversial whether GSK3β is a “tumor suppressor” or “tumor promoter.” Available evidence indicates that GSK3β may function as a “tumor suppressor” for certain types of tumors, such as skin and mammary tumors; GSK3β overexpression/activation inhibits neoplastic transformation and development of these tumors. On the other hand, GSK3β may act as a “tumor promoter” for other types of tumors, such as colon and pancreatic cancers, and enhance carcinogenesis. Under the circumstances, GSK3β inhibitors may provide an effective therapeutic avenue for the treatment of these tumors. Although the mechanisms underlying the differential effects of GSK3β remain to be elucidated, both anti-tumor and pro-tumor properties of GSK3β need to be carefully evaluated when a therapeutic strategy is being developed to target GSK3β.

Acknowledgments

I’d like to thank Kimberly A. Bower for reading this manuscript. This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AA015407 and AA017226).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jope RS, Yuskaitis CJ, Beurel E. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3): inflammation, diseases, and therapeutics. Neurochem Res. 2007;32:577–595. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9128-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woodgett JR. Physiological roles of glycogen synthase kinase-3: potential as a therapeutic target for diabetes and other disorders. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord. 2003;3:281–290. doi: 10.2174/1568008033340153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doble BW, Woodgett JR. GSK-3: tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1175–1186. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grimes CA, Jope RS. The multifaceted roles of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta in cellular signaling. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;65:391–426. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(01)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plytes SE, Hughes K, Nikolakaki E, Pulverer BJ, Woodgett JR. Glycogen synthase kinase-3: functions in oncogenesis and development. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1114:147–162. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(92)90012-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beurel E, Jope RS. The paradoxical pro- and anti-apoptotic actions of GSK3 in the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis signaling pathways. Prog Neurobiol. 2006;79:173–189. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Billadeau DD. Primers on molecular pathways. The glycogen synthase kinase-3beta. Pancreatology. 2007;7:398–402. doi: 10.1159/000108955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manoukian AS, Woodgett JR. Role of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in cancer: regulation by Wnts and other signaling pathways. Adv Cancer Res. 2002;84:203–229. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(02)84007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ougolkov AV, Billadeau DD. Targeting GSK-3: a promising approach for cancer therapy? Future Oncol. 2006;2:91–100. doi: 10.2217/14796694.2.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seldin DC, Landesman-Bollag E, Farago M, Currier N, Lou D, Dominguez I. CK2 as a positive regulator of Wnt signalling and tumourigenesis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;274:63–67. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-3078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartigan JA, Xiong XC, Johnson GV. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta is tyrosine phosphorylated by PYK2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;284:485–489. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartigan JA, Johnson GV. Transient increases in intracellular calcium result in prolonged site-selective increases in Tau phosphorylation through a glycogen synthase kinase 3beta-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21395–21401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.21395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lesort M, Jope RS, Johnson GV. Insulin transiently increases tau phosphorylation: involvement of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta and Fyn tyrosine kinase. J Neurochem. 1999;72:576–584. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi-Yanaga F, Shiraishi F, Hirata M, Miwa Y, Morimoto S, Sasaguri T. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta is tyrosine-phosphorylated by MEK1 in human skin fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;316:411–415. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baltzis D, Pluquet O, Papadakis AI, Kazemi S, Qu LK, Koromilas AE. The eIF2alpha kinases PERK and PKR activate glycogen synthase kinase 3 to promote the proteasomal degradation of p53. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:31675–31687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704491200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lustig B, Behrens J. The Wnt signaling pathway and its role in tumor development. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2003;129:199–221. doi: 10.1007/s00432-003-0431-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leis H, Segrelles C, Ruiz S, Santos M, Paramio JM. Expression, localization, and activity of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta during mouse skin tumorigenesis. Mol Carcinog. 2002;35:180–185. doi: 10.1002/mc.10087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding Q, He X, Xia W, Hsu JM, Chen CT, Li LY, Lee DF, Yang JY, Xie X, Liu JC, Hung MC. Myeloid cell leukemia-1 inversely correlates with glycogen synthase kinase-3beta activity and associates with poor prognosis in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4564–4571. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma C, Wang J, Gao Y, Gao TW, Chen G, Bower KA, Odetallah M, Ding M, Ke Z, Luo J. The role of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta in the transformation of epidermal cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7756–7764. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farago M, Dominguez I, Landesman-Bollag E, Xu X, Rosner A, Cardiff RD, Seldin DC. Kinase-inactive glycogen synthase kinase 3beta promotes Wnt signaling and mammary tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5792–5801. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Lam JB, Lam KS, Liu J, Lam MC, Hoo RL, Wu D, Cooper GJ, Xu A. Adiponectin modulates the glycogen synthase kinase-3beta/beta-catenin signaling pathway and attenuates mammary tumorigenesis of MDA-MB-231 cells in nude mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11462–11470. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong J, Peng J, Zhang H, Mondesire WH, Jian W, Mills GB, Hung MC, Meric-Bernstam F. Role of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta in rapamycin-mediated cell cycle regulation and chemosensitivity. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1961–1972. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding Q, He X, Hsu JM, Xia W, Chen CT, Li LY, Lee DF, Liu JC, Zhong Q, Wang X, Hung MC. Degradation of Mcl-1 by beta-TrCP mediates glycogen synthase kinase 3-induced tumor suppression and chemosensitization. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4006–4017. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00620-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doble BW, Woodgett JR. Role of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in cell fate and epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Cells Tissues Organs. 2007;185:73–84. doi: 10.1159/000101306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou BP, Hung MC. Wnt, hedgehog and snail: sister pathways that control by GSK-3beta and beta-Trcp in the regulation of metastasis. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:772–776. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.6.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guarino M, Rubino B, Ballabio G. The role of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer pathology. Pathology. 2007;39:305–318. doi: 10.1080/00313020701329914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thiel A, Heinonen M, Rintahaka J, Hallikainen T, Hemmes A, Dixon DA, Haglund C, Ristimäki A. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 is regulated by glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in gastric cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4564–4569. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512722200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gotoh J, Obata M, Yoshie M, Kasai S, Ogawa K. Cyclin D1 over-expression correlates with beta-catenin activation, but not with H-ras mutations, and phosphorylation of Akt, GSK3 beta and ERK1/2 in mouse hepatic carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:435–442. doi: 10.1093/carcin/24.3.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cao Q, Lu X, Feng YJ. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta positively regulates the proliferation of human ovarian cancer cells. Cell Res. 2006;16:671–677. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shakoori A, Ougolkov A, Yu ZW, Zhang B, Modarressi MH, Billadeau DD, Mai M, Takahashi Y, Minamoto T. Deregulated GSK3beta activity in colorectal cancer: its association with tumor cell survival and proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334:1365–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shakoori A, Mai W, Miyashita K, Yasumoto K, Takahashi Y, Ooi A, Kawakami K, Minamoto T. Inhibition of GSK-3 beta activity attenuates proliferation of human colon cancer cells in rodents. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1388–1393. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00545.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ougolkov AV, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Savoy DN, Urrutia RA, Billadeau DD. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta participates in nuclear factor kappaB-mediated gene transcription and cell survival in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2076–2081. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ougolkov AV, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Bilim VN, Smyrk TC, Chari ST, Billadeau DD. Aberrant nuclear accumulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in human pancreatic cancer: association with kinase activity and tumor dedifferentiation. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5074–5081. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Erdal E, Ozturk N, Cagatay T, Eksioglu-Demiralp E, Ozturk M. Lithium-mediated downregulation of PKB/Akt and cyclin E with growth inhibition in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2005;115:903–910. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liao X, Zhang L, Thrasher JB, Du J, Li B. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta suppression eliminates tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand resistance in prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:1215–1222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mazor M, Kawano Y, Zhu H, Waxman J, Kypta RM. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 represses androgen receptor activity and prostate cancer cell growth. Oncogene. 2004;23:7882–7892. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ougolkov AV, Bone ND, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Kay NE, Billadeau DD. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity leads to epigenetic silencing of nuclear factor kappaB target genes and induction of apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Blood. 2007;110:735–742. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-060947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kunnimalaiyaan M, Vaccaro AM, Ndiaye MA, Chen H. Inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta, a downstream target of the raf-1 pathway, is associated with growth suppression in medullary thyroid cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1151–1158. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcea G, Manson MM, Neal CP, Pattenden CJ, Sutton CD, Dennison AR, Berry DP. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta; a new target in pancreatic cancer? Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7:209–215. doi: 10.2174/156800907780618266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cai G, Wang J, Xin X, Ke Z, Luo J. Phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta at serine 9 confers cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2007;31:657–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beurel E, Kornprobst M, Blivet-Van Eggelpoel MJ, Ruiz-Ruiz C, Cadoret A, Capeau J, Desbois-Mouthon C. GSK-3beta inhibition by lithium confers resistance to chemotherapy-induced apoptosis through the repression of CD95 (Fas/APO-1) expression. Exp Cell Res. 2004;300:354–364. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beurel E, Kornprobst M, Blivet-Van Eggelpoel MJ, Cadoret A, Capeau J, Desbois-Mouthon C. GSK-3beta reactivation with LY294002 sensitizes hepatoma cells to chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Int J Oncol. 2005;27:215–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soto-Cerrato V, Viñals F, Lambert JR, Kelly JA, Pérez-Tomás R. Prodigiosin induces the proapoptotic gene NAG-1 via glycogen synthase kinase-3beta activity in human breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:362–369. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li Z, Tan F, Thiele CJ. Inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta contributes to brain-derived neutrophic factor/TrkB-induced resistance to chemotherapy in neuroblastoma cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:3113–3121. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tan J, Zhuang L, Leong HS, Iyer NG, Liu ET, Yu Q. Pharmacologic modulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta promotes p53-dependent apoptosis through a direct Bax-mediated mitochondrial pathway in colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9012–9020. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Behrens J, Lustig B. The Wnt connection to tumorigenesis. Int J Dev Biol. 2005;48:477–487. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041815jb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herbst A, Kolligs FT. Wnt signaling as a therapeutic target for cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;361:63–91. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-208-4:63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoeflich KP, Luo J, Rubie EA, Tsao MS, Jin O, Woodgett JR. Requirement for glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in cell survival and NF-kappaB activation. Nature. 2000;406:86–90. doi: 10.1038/35017574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eferl R, Wagner EF. AP-1: a double-edged sword in tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:859–868. doi: 10.1038/nrc1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saez E, Rutberg SE, Mueller E, Oppenheim H, Smoluk J, Yuspa SH, Spiegelman BM. c-fos is required for malignant progression of skin tumors. Cell. 1995;82:721–732. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90469-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Young MR, Li JJ, Rincon M, Flavell RA, Sathyanarayana BK, Hunziker R, Colburn N. Transgenic mice demonstrate AP-1 (activator protein-1) transactivation is required for tumor promotion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9827–9832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang C, Schmid PC, Ma WY, Schmid HH, Dong Z. Phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase is necessary for 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-induced cell transformation and activated protein 1 activation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4187–4194. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang C, Ma WY, Young MR, Colburn N, Dong Z. Shortage of mitogen-activated protein kinase is responsible for resistance to AP-1 transactivation and transformation in mouse JB6 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:156–161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen F, Castranova V. Nuclear factor-kappaB, an unappreciated tumor suppressor. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11093–11098. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perkins ND. NF-kappaB: tumor promoter or suppressor? Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bournat JC, Brown AM, Soler AP. Wnt-1 dependent activation of the survival factor NF-kappaB in PC12 cells. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61:21–32. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000701)61:1<21::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim SD, Yang SI, Kim HC, Shin CY, Ko KH. Inhibition of GSK-3beta mediates expression of MMP-9 through ERK1/2 activation and translocation of NF-kappaB in rat primary astrocyte. Brain Res. 2007;1186:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sui Z, Sniderhan LF, Fan S, Kazmierczak K, Reisinger E, Kovács AD, Potash MJ, Dewhurst S, Gelbard HA, Maggirwar SB. Human immunodeficiency virus-encoded Tat activates glycogen synthase kinase-3beta to antagonize nuclear factor-kappaB survival pathway in neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:2623–2634. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ryves WJ, Harwood AJ. The interaction of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) with the cell cycle. Prog Cell Cycle Res. 2003;5:489–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]