Abstract

Plasma treatments are emerging as superior efficiency treatment for high surface to volume ratio materials to tune functional group densities and alter crystallinity due to their ability to interact with matter at the nanoscale. The purpose of this study is to assess for the first time the long term stability of surface functional groups introduced across the surface of carbon nanotube materials for a series of oxidative, reductive and neutral plasma treatment conditions. Both plasma duration dose matrix based exposures and time decay experiments, whereby the surface energy of the materials was evaluated periodically over a one-month period, were carried out. Although only few morphological changes across the graphitic planes of the carbon nanotubes were found under the uniform plasma treatment conditions, the time dependence of pertinent work functions, supported by Raman analysis, suggested that the density of polar groups decreased non-linearly over time prior to reaching saturation from 7 days post treatment. This work provides critical considerations on the understanding of the stability of functional groups introduced across high specific surface area nano-materials used for the design of nano-composites, adsorptive or separation systems, or sensing materials and where interfacial interactions are key to the final materials performance.

The nature of the temporal stability of functional groups introduced across the surface of nano-materials is critical to the development of advanced materials for applications where surface-specific interactions or reactions determine performance. The density, distribution and type of functional groups introduced on the surface of nano-particles will provide synergistic effects to control interfaces across nano-composites, but also interactions with probe molecules during sensing or catalysis reactions, and affect separation performance if used as adsorbent or membrane materials.

Specifically, the surface functionalization of sp2 hybridized materials, such as graphene sheets or carbon nanotubes (CNTs), represents a challenge due to the inherent crystallinity and chemical stability of these unsaturated materials1,2. Approaches to finely tune the surface coverage and position of functional groups across the surface of graphitic planes have been developed to modify the physico-chemical properties of these materials at the nanoscale. The aim of such treatments is to facilitate specific interactions that prevent agglomeration during processing and incorporate CNTs uniformly into mixed matrix composite materials3,4,5. Other important aspects are concerned with increasing structural interactions between graphitic materials6,7, or enhancing surface-bound properties of materials in relation to plasmons or general adsorption7,8. The natural hydrophobicity of native graphite and graphene is due to the intrinsically non-polar structure consisting of aromatic ‘honeycomb’ sheets, which consequently show little affinity to highly polar molecules such as water9,10. Thus the purpose of the graphene-based materials chemistry in this regard is to enhance the scope and range of applications by either improving the chemical interaction potential or establishing covalent bridges to the surrounding matrix11,12,13,14.

Pathways to chemically modify graphene based materials are aiming to either open aromatic rings of sp2 hybridized structure or react with chemical groups attached to defect sites on graphitic planes. Types of treatment include chemical reactions in solution as well as exposure to sources of radiation (such as x-ray, gamma ray or ultra violet), reactive gases like ozone and radicals from plasmas15,16,17. Solution reactions are by far the most wide-spread of all surface-bound functionalization routes and are typically governed by fast kinetics of reaction. However, practical issues related to constraints in storing CNT suspensions due to particle agglomeration, the colloidal stability as a function of the pH or the functionalization of CNT are limiting potential applications to a relatively narrow range of surface modifications10,18. Moreover, due to the highly reactive nature of conditions required to apply these treatments, e.g. through the use of chemicals such as H2SO4 or HNO3, significant damage is often introduced to the sidewalls and tips of CNTs treated in this way16,19,20. In fact, attaching covalently-bound functional groups to CNT or graphene structures will always lead to local defect formation and re-arrangement of the graphitic lattice prior to orbital de-hybridization when planar sp2 bonds are transformed to sp3 bonds. The grafting of complex macro-molecules via solution modification typically requires a series of reactions, involving multiple cleaning and purification procedures, to process graphene materials, leading to low reaction yields21,22. On the other hand the high penetration power of radiation-based reactions, such as x-ray or gamma ray irradiation, allows treatments to be performed in the gas phase that are not limited to the material surface. Nonetheless they were shown to homogeneously functionalize many layers of graphene tens of microns thick23,24,25. Radiation is extremely efficient at altering the crystalline structure of graphitic planes and interact with defects within the structure to promote simple forms of functionalization, such as grafting of carboxylic, amine or hydroxyl groups. However, the capacity of this technique to graft more complex functional groups is limited to reagents which can be brought into physical contact with the target sites23,26,27. The same applies to UV, ozone and plasma, however these treatments provide extensions to the range of surface modifications available for graphene materials7,28,29. Reactive gas plasma treatments and polymerization by plasma enhanced chemical vapour deposition (PECVD) offer the possibility to chemically and morphologically tune material surfaces by introducing new functionalities through a process that is friendly to the environment, quick and highly efficient.

Recent work on plasma treatments have shown that complex series of functionalization, grafting or coating steps can be applied to enhance surface properties of meta-materials in terms of electrical conductivity, surface abrasion resistance and surface energy30. Another fundamental challenge is related to controlling plasma conditions in order to vary the impact the process has on the crystallinity of the material and the level of damage it inflicts on the structure, possibly altering texture and molecular order at the nano or meso scale31. It was previously shown that the number of defects generated across highly crystalline materials was primarily dependent on plasma excitation power, the partial pressure of the feed gas and treatment time due to the effect these parameters have on plasma density, electromagnetic radiation and flux of ionized matter32,33,34. These findings imply that plasma parameters need to be finely tuned to obtain the most suitable result for a certain target application. The reactivity of surfaces after plasma treatment is still being debated, since the stability of functional groups introduced across CNTs upon plasma treatment has not been discussed to date and it is essential to evaluate the long-term efficiency of this fabrication route towards a possible scale-up. The levels of hybridization of graphitic plans, and the reactivity of vacancies generated upon activation may lead to a number of functionalization pathways depending on the type of species present within the plasma glow. Stochastic generation of radicals within the plasma would lead to the formation of both sp3 bonds which may rehybridize into sp2 states. It has been shown that even an inert feed gas, such as Argon, has the capacity to produce oxygenated functionalities when reactive chemical surface groups generated by the plasma treatment are brought in contact with oxygen from the air35. Reported applications for plasma treatments applied to graphene based materials include tuning interactions of treated material with the environment, which favor the attachment of certain molecular groups over others, as well as the etching and cleaning of surfaces36,37,38. Several studies have been carried out to demonstrate how molecular reactants such as nitrogen, ammonia or oxygenated gases and vapours can be used for plasma treatment39,40,41. The interaction of the free radicals generated by the plasma with the surface of graphene materials has, however, not been studied to date. The assessment of the long-term stability of surface groups generated by the plasma is critical to its role for manufacturing in general, where graphene sheets or carbon nanotubes are modified for the purpose of incorporating them into complex hierarchical materials42,43.

The aim of this work is to evaluate the lasting impact of plasma treatments on carbon nanotube bucky-papers (BPs). This study was performed in order to gauge the reactivity of the CNTs and hence that of other graphene based materials, to different plasma environments (oxidative, reductive and neutral) and to quantify the density and type of functional groups that are created by the treatment. It also seeks to quantify the damage caused by the plasma treatment to the crystalline structure of the CNTs as a function of specific conditions. X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS), Raman spectroscopy and Photoelectron Spectroscopy in Air (PESA) measurements were performed on the treated samples to monitor the degree and type of functionalisation, structural damage to the CNTs, and the surface work function, respectively. The long term stability of functional groups introduced onto the CNTs was investigated by characterizing the samples at set periods up to 1 month post treatment. The different plasma treatments were compared, with results illustrating the potential of pertinent plasma treatment techniques for mass production of graphene based materials exhibiting versatility and characterized by excellent chemical stability.

Results and Discussions

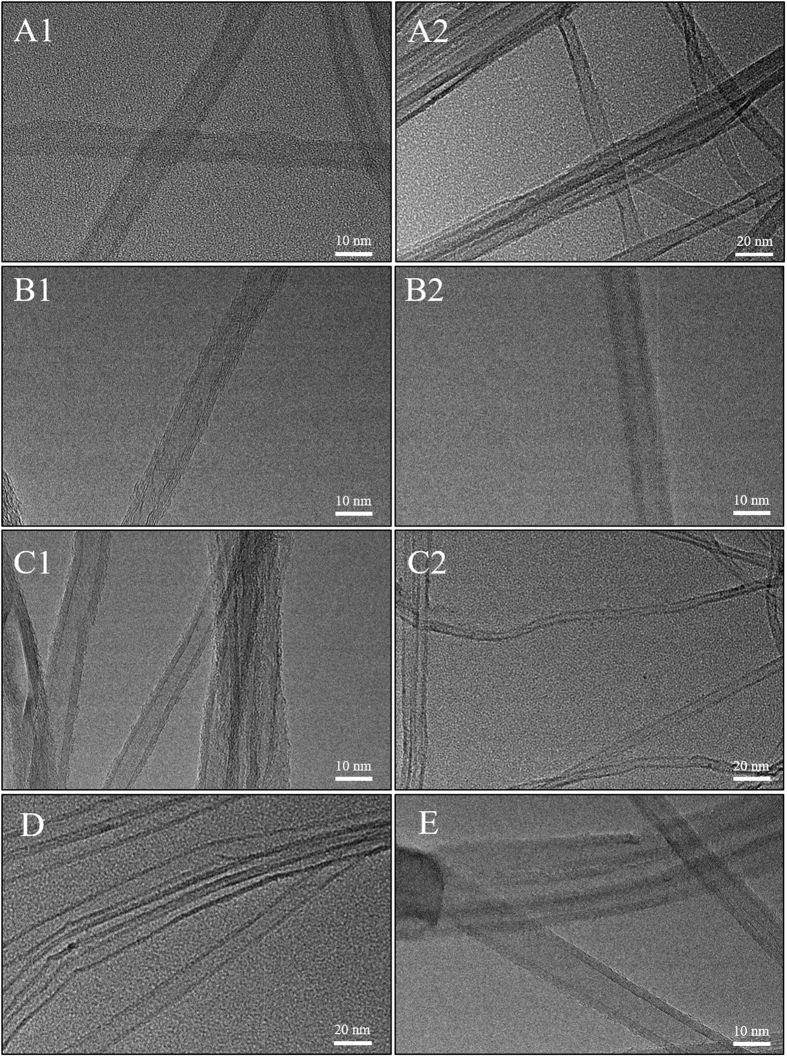

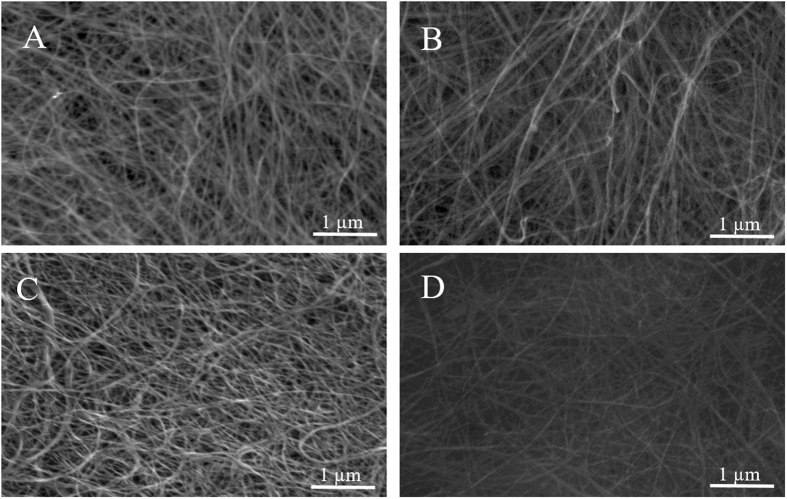

The impact of the plasma treatments on the morphology of the CNTs was investigated by evaluating the integrity of the crystalline graphitic walls in terms of the presence of damage. The structure of the untreated CNTs were compared to that of the plasma modified samples across the TEMs in Fig. 1 and Figure S1. Although the outer wall profiles seemed to be affected by the treatment, showing slight breakages all along the tubes, no severe damage could be seen up to 30 min of plasma treatment, regardless of the nature of the gas feed. Consequently, the plasma conditions could be considered gentle enough to preserve the physical structure of the samples even at longer treatments while the nature of the gas as reducing, oxidizing or inert, cannot be directly related to these effects since the micrographs do not show any significant difference across the series. The TEM analysis was confirmed by a long range SEM analysis as shown in Fig. 2. The surface modifications did not generate major physical damages on the pristine substrate presented in Figure S2, suggesting that the material crystallinity was largely unaffected by the plasma treatments. Furthermore, no evidence of a possible correlation between the feed gas and the final physical structure can be inferred since apparently there is no difference across the series of different gas. Interestingly the exposure duration does not seem to have an impact in terms of damage as no remarkable differences can be assumed comparing shorter treatments, presented in Figure S3, with the longest.

Figure 1.

Transmission Electron Micrographs (TEMs) of CNTs under different conditions: reference (A1,A2), plasma treated with O2/Ar (B1,B2) for 1 min and 30 min respectively, plasma treated with H2/Ar (C1,C2) for 1 min and 30 min respectively, CO2 5 min (D) and Ar 30 min (E).

Figure 2.

Scanning Electron Micrographs (SEMs) of plasma treated BPs for 30 min with O2/Ar (A), H2/Ar (B), CO2 (C) and Ar (D) respectively.

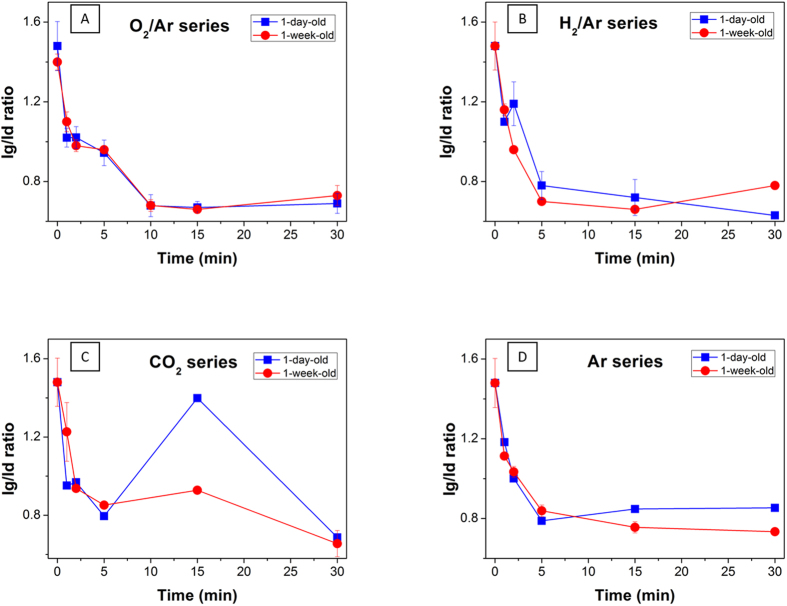

As shown in Fig. 3, the level of disorder associated with the structure and the introduction of defects was evaluated by comparing Raman spectra across various series of different plasma durations as well as different gases. The nature of the disorder which may have been introduced by the plasma treatments and the quantification of the amount of damage, were related to the main plasma parameters including plasma gas and duration. Raman scattering on functionalized CNTs are therefore performed to evaluate the intensity of the G- and D-bands of the Raman spectra to quantify the amount of defects generated in the lattice. A quantitative analysis on the defects occurring across graphitic plans may be assessed typically by analyzing the Ig/Id ratio corresponding to the G and D bands at 1583 cm−1 and 1352 cm−1 respectively44. The G-band represents the tangential stretching vibration of the in-plane C-C bonds in the graphitic structure while the D-band is a double-resonance Raman mode generated by the inelastic scattering of a phonon and elastic scattering induced by a defect45. While the G-band is taken into account to discuss the graphitic lattice of the CNTs, the D-band is attributed to the presence of disorder in graphitic materials. All the spectra were normalized on the G’ band occurring at 2705 cm−1, the variation of the G and D bands over time duration for O2/Ar series is reported in Figure S4 as an indicative example. In addition to providing evidence of the introduction of functional groups, the Ig/Id ratio may be used to quantify the amount of amorphous sp3 carbons generated from damage on the walls of the CNTs46 although the technique itself cannot provide a definitive qualitative measure for functional groups that are present. The investigation was conducted via a series of plasma treatment durations, while the samples were analysed within 6 h of treatment to minimize effects from oxidation in air. For these series, a significant drop of the Ig/Id ratio between the pristine BP and the 1 min treated sample is reported for each feed gas. The ratio decreases by approximately 31%, from 1.48 to 1.02 for the O2/Ar series and by 36% drop at 0.92 for the CO2 series. The weakest plasma impact was obtained initially for Ar, where Ig/Id is dropping to 1.18 under comparable conditions. Interestingly, the ratio is plateauing for longer treatment durations in the vicinity of 0.75 for any of the different reactant gases. The pronounced initial change of the Ig/Id ratio can be interpreted as that the plasma was contributing significantly to the introduction of defects and possibly new functional groups within the first few minutes of treatment. This can be further confirmed by the analysis of the Raman spectra of each feed gas, reported in Figure S, where a shoulder at 1620 cm−1 defined as D’ band arises at the 5 min mark across the series45,47 along with the introduction of new functional groups. This result is in good accordance with previous studies48,49 and can be used to confirm the increased disorder due to functionalization.

Figure 3.

Raman Ig/Id ratio of the O2/Ar series (A), (B) H2/Ar, (C) CO2 and (D) Ar.

The surface lattice eventually reaches a saturation level whilst a longer exposure to plasma produces no dramatic introduction of new functional groups. Interestingly, the H2/Ar and the pure Ar series, corresponding to neutral and reductive gases lead to Ig/Id ratios of 1.1 and 1.18 respectively after 1 min of exposure, suggesting that the nature of the gases involved is critical to control the level of damage introduced on the lattice for short treatment durations. This is further confirmed by the fact that even though all the series seem to reach a saturation level, the plateau is still at different Ig/Id ratios spanning from 0.77 for the Ar series to 0.63 for the H2/Ar. Consequently, it may be inferred that the effect of exposure duration on surface damage is relevant only for shorter treatments and becomes insignificant when saturation is reached. In that scenario it can be assumed that the nature of the reactant gas is what determines the nature of the physical damage.

During the plasma functionalization, different molecules may be formed following the proposed mechanisms described in former studies35,50,51, related to the presence of ions and radicals generated from the feed gas within the plasma glow. In the case of an inert gas, such as Ar, the activated species may interact as metastable positive ions along with the generated electrons with the surface scavenging reactive groups and creating more activated sites52. These sites, consisting initially of radicals generated on the surface, can therefore react with the active molecules present in the complex plasma atmosphere depending on the reactant gas used, leading to the formation of covalent bonds and resulting eventually in the grafting of chemical groups51. As for the oxygen plasma, the attack of the oxygen radicals for the gas considered, would likely lead to the formation of activated sites and then of C-O bonds on the surface of the BPs. Hydroxyl bonds are formed on stabilization by hydrogen atom transfer from the neighbors or on exposure to atmosphere after plasma treatment via interactions with humidity in the air and subsequent stabilization by hydrogen atom transfer from moisture, while carbonyl bonds are the consequence of an intramolecular reorganization of C-C bonds. Conversely the carboxylic groups are formed from active sites near previously generated carbonyl bonds after stabilization due to a proton transfer51.

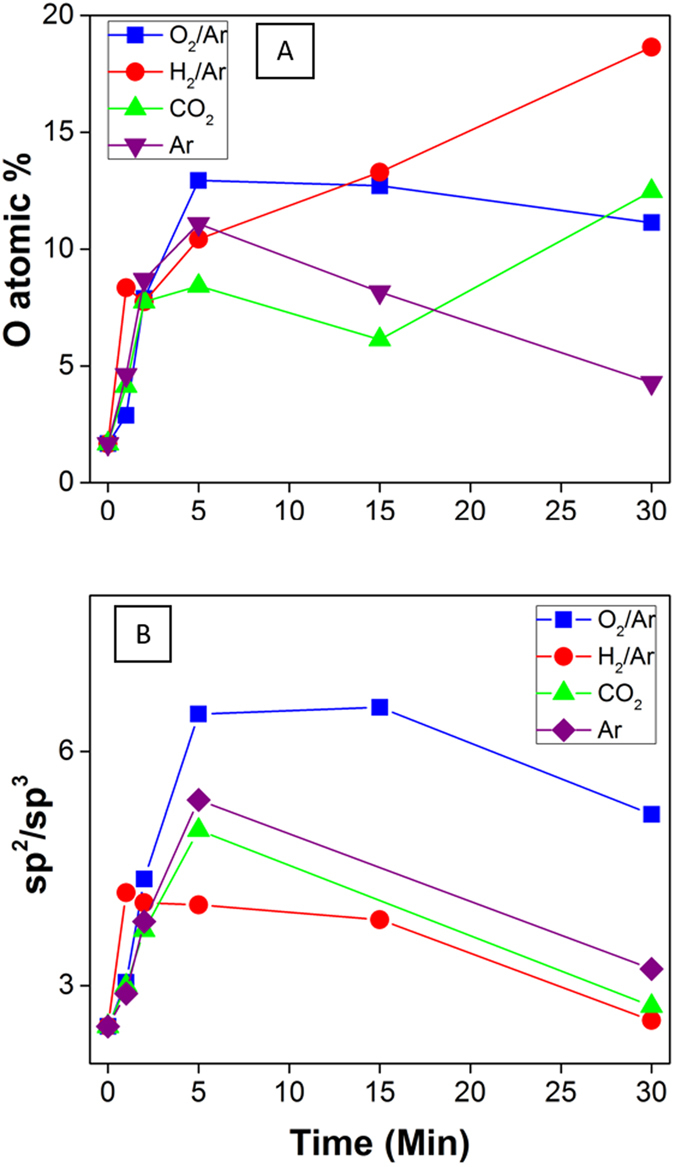

The nature of such changes in surface chemistry after plasma treatment is supported by results from XPS analysis. Figure 4A shows the evaluation of the oxygen (O) atomic concentration across the series calculated from the XPS survey showed in Figure S5 as well as the variation of sp2 and sp3 carbon which is relevant to assess the loss in graphitic structure. Interestingly, the main changes in O at% occurred within 5 min of plasma treatment, raising from 1.7 at% of the reference to 11.1 at% and 12.9 at% for the Ar and O2/Ar series respectively, representing the lowest and highest shifts. A similar oxygen content increase was observed from low-temperature thermal annealing under vacuum when the annealing time exceeded 2 h53. An increase in chemical activity was suggested as a possible cause for this sudden rise in the atomic concentration of oxygen, which occurred most likely when the sample was returned from vacuum to atmosphere. Whilst for the first 5 min the trend for each feed gas is the same with the observed remarkable increase in oxygen content, this increase was found to stop for longer treatments with the exception of the H2/Ar series for which the increase continued at a slower rate. It is assumed that the deviating trend for H2/Ar may be caused by further reaction pathways occurring between the activated CNT surfaces and oxygen in the air outside the plasma chamber and prior to storage in a dry environment. As observed for Ar-ion bombardment inside an XPS [54] or an ion gun53, the exposure to Ar plasma was reducing the atomic oxygen content for longer treatment times. Nonetheless, the analysis of the sp2 carbon suggests that the O2/Ar series is clearly the least costly in terms of lattice structural damage, showing a low 3% loss when compared to Ar, CO2 and H2/Ar which produced losses of 17%, 15% and 22%, respectively. These important results, considered in conjunction with those from the Raman analysis where a significant drop in the Ig/Id ratio was observed for all reactant gases in the first 5 minutes of treatment, suggest that for the O2/Ar series this drop is due to an actual introduction of functional groups containing oxygen, consuming amorphous sp3 carbon in the structure, rather than affecting the graphene sheets. This interpretation would be consistent with a stark drop in sp3 C for all reactant gases, while the sp2 C fraction for O2/Ar plasma remained essentially constant. Conversely, the H2/Ar plasma is reported to lead to the highest decrease in sp2 bonds with increasing treatment time while the sp3 structure is less affected when compared to the O2/Ar series, as shown in S6a,b. This result is consistent with the studies carried out on diamond-like carbon (DLC) where the H2 plasma exposure of thin films has been shown to etch away unsaturated bonds while increasing the sp3 content54.

Figure 4.

(A) Oxygen atomic concentration, (B) sp2/sp3 carbon ratio evaluated by X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS) across the different series: O2/Ar (blue), H2/Ar (red), CO2 (green), Ar (purple) at different plasma treatment duration.

The sp2/sp3 ratio was calculated, from the XPS data, for the series of samples. The sp2/sp3 ratio corresponds to ratio of the C=C to C-C carbon atoms. The graphitic walls of the pristine CNTs are solely composed of C=C bonds. However defects, either in the form of adduct groups, generated from a single C-C bond dissociation and corresponding to sp3 hybridized carbon atoms, or from multiple C-C bonds dissociation leading to functional groups generation. Stripping of carbon atoms from the main lattice may also generate either adduct defects or functionalization with oxygen rich groups, such as epoxy, carboxylate or hydroxyl51.

As seen in Fig. 4B, the sp2/sp3 ratio initially increased for short plasma durations, up to 5 min, prior to strongly decreasing for all plasma gases with longer plasma durations. The initial increase is attributed to the activation of the surface leading to a partial but rapid removal of sp3 hybridized atoms, known to be more reactive than sp2. Past 5 min, it is likely that excess energy input led to the breakage of bonds bridging sp2 carbons, which led to the sharp degree of functionalization as seen in Figs 4A and 5A–C. The oxygen content was in fact extremely well inversely correlated with the sp2/sp3 ratio and the amount of carboxylate and hydroxyl groups calculated from the XPS carbon peaks deconvolution. This result is in excellent agreement with previous calculations of bond energy dissociations and for CNT graphitic plans55. It therefore can be assumed that the rise in sp3 carbon shown for long treatment duration is due to the conversion of the sp2 structure with the formation of C-H functionalities, occurring only after a long exposure given the low concentration of hydrogen, 2%, as reported. The effective change is best gauged by comparing the H2/Ar result to pure Ar. In contrast, the absence of a reductive agent when O2/Ar is used leads to a more extensive reaction of amorphous carbon, consistent with the greater reactivity previously attributed to such sites in the literature. This assumption is confirmed in Figure S6a,b showing a significant drop in sp3 hybridization from 23.8 at% to 9.1 at% within the first 5 min for the O2/Ar series34.

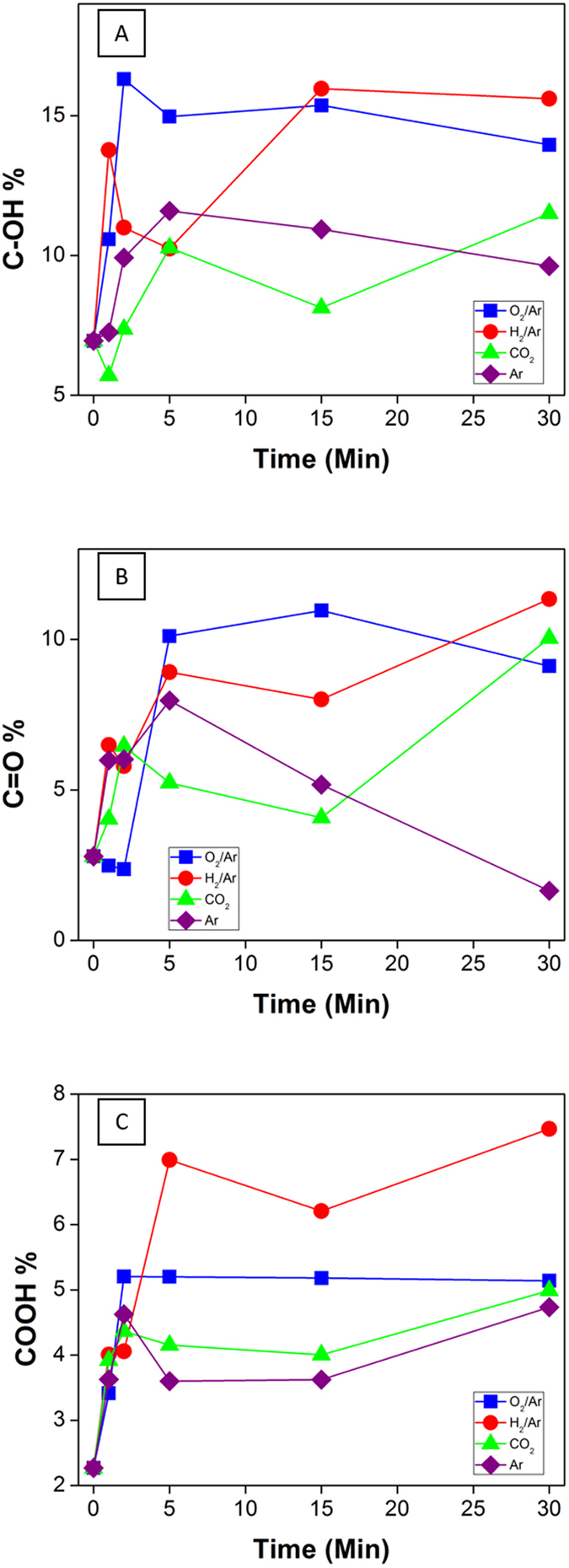

Figure 5.

(A) relative content on the C1s spectra of C-OH (A), C=O (B), COOH (C) bonds evaluated by X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS) across the different series: O2/Ar (blue), H2/Ar (red), CO2 (green), Ar (purple) at different plasma treatment time.

Furthermore, an in-depth analysis was carried out on the XPS results to determine the type and extent of specific functional groups generated by the plasma treatment. The XPS data was deconvoluted into 5 Gaussian peaks centred at 284.5, 285.2, 286.2, 287.7, 288.9 and 291.2 eV which are assigned to sp2 carbon, sp3 carbon, C-OH, C=O, COOH, and π- π* respectively. The results of this analysis are given in Fig. 5 (π- π* transition in Figure S6c) and in Figures S7–S10, presenting the high resolution spectra of C1s for each series, and broadly confirm the chemical pathway previously discussed. To establish a correlation between the type of carbon-hybridization and surface functional groups on CNT it is necessary to take into account that hydroxyl groups are associated most likely with the sp2 hybridization of carbon and a lattice defect or an edge, while carbonyl and carboxylate groups are associated with sp3 hybridization. The XPS graphs reveal that the hydroxyl groups represent the largest fraction of oxygen rich groups with the O2/Ar series emerging as the most efficient reactant gas that produces this functionality with an absolute maximum at 16.3%. The generation of hydroxyl groups is furthermore consistent with a minimal change in sp2 hybridization observed for this reactant gas. Interestingly, as already reported for the Raman scattering and the atomic elemental content, all the series saturate at longer treatment durations with the most significant changes occurring within the first 5 minutes of exposure. Oxygen surface saturation is therefore taking place across the surface when the sample is exposed to air after treatment, and minor changes between series are probably due to a re-arrangement of the graphitic walls from and with the significant amount of remaining activated sites. Carboxylic groups were found more predominantly with the H2/Ar treatments plateauing at 6.9% while the O2/Ar treatment clearly shows a surface saturation, plateauing at 5.2% after a short exposure of 2 min to the plasma environment. Interestingly, the H2/Ar gas also shows the most significant drop in sp2 carbon, down to an absolute minimum of 45.8% which can be correlated either to reduction reactions between the hydrogen radicals56 or to the breakage of C=C bonds by the H+ ions54,57 or H radicals which, conversely, stabilizes the sp3 C-C content. These results match previous studies where H2 plasma treatments were found to drastically reduce the electrical conductance upon treatment, with the loss of C=C bonds56,58. The decrease in π- π* transition content, shown in Figure S6c, which exhibits an sp2 satellite peak59, supports the analysis in terms of loss in sp2 hybridization particularly relevant for the H2/Ar series, as discussed. The lowest rates of reactions were obtained for the Ar gas with only a 14.3% final oxygen content and 4% plateauing for the carboxylic groups, which is in good agreement with the literature since this gas mostly accounts for physical etching35,60.

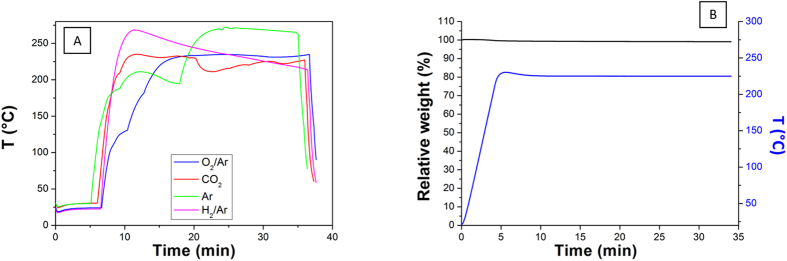

Potential thermal damage from the plasma was also assessed. Since the plasma temperature during the treatment under the experimental conditions was found to raise above 200 °C, as shown in Fig. 6, a TGA analysis was performed on a reference BP in order to potentially rule out the decomposition of the sample as an impact factor on the Raman results. Figure 6 reveals that the original weight is almost retained up to that temperature, with less than 0.9 wt% of loss, attributed to water evaporation below 100 °C. This result suggests that the temperature is neither decomposing the structure nor affecting results from other techniques used to perform measurements for this study to evaluate type and magnitude of physical modifications occurring on the surface. Furthermore, according to the XPS patterns for the different C-O bonds introduced, since the relative content in each case across the series seems to reach a plateau this parameter can be likely considered as ineffective to vary or to tune the specific C-O bond content.

Figure 6.

(A) Representative plasma temperatures for each 30-min sample showing that the temperature is almost constantly above 200 °C, and (B) TGA analysis in air of a reference BP.

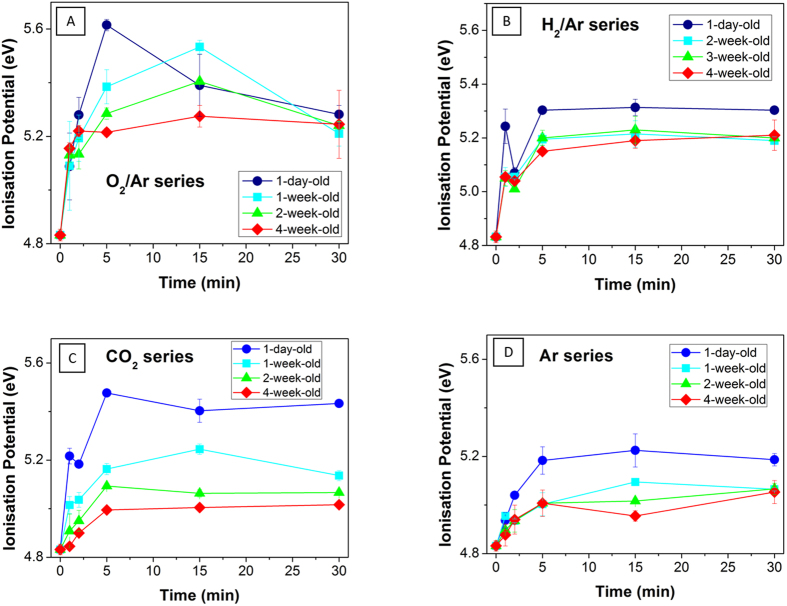

The ionization potential (IP) of the CNT BPs was measured by PESA at various stages post-treatment (Fig. 7) to assess the degree of functionalisation and its temporal stability. The IP corresponds to the energy required to remove a surface atom electron from sample surface to the vacuum level61 and, in the case of metallic materials, is equivalent to the work function. As such the IP is highly sensitive to the state of the surface and is affected by surface contamination, the surface chemistry, surface functional groups and their density, as well as the degree of crystallinity62,63. It is therefore an excellent tool to further gauge the effects of the 4 plasma treatments under investigation here.

Figure 7.

Ionisation potential as a function of treatment time (1, 2, 5, 15 and 30 min) with the following plasmas (A) O2/Ar, (B) H2/Ar (B), (C) CO2 and (D) Ar. IP values are shown for samples stored in air for 1 day, 1, 2 and 4 weeks post-plasma treatment.

As seen in Fig. 7, plasma treatment led to a rapid increase in the IP over the first 5 min, regardless of the plasma type. The IP then leveled off (H2/Ar, CO2, Ar) or decreased slightly (O2/Ar) with further treatment duration. While all of the treatments were effective in increasing the IP, the greatest increase was observed for O2/Ar with an IP value of 5.6 eV after only 5 min of treatment, compared to 5.4, 5.3 and 5.2 eV for CO2, H2/Ar and Ar plasma glows, respectively. The increased work function is attributed to a combination of the introduction of oxygen functional groups at the surface and the resulting oxygen surface dipoles created, and a reduction in pi conjugation bonding (e.g. reduced sp2/sp3 ratio)64,65. CNTs functionalized with oxidative treatments, such as pure O2 or an acid treatment commonly exhibit increased IPs62. This trend is also consistent with the XPS results which showed a strong increase in hydroxyl, carbonyl and carboxylic groups at the surface for all of the plasma treatments, especially O2/Ar and H2/Ar, and a considerable decrease in the sp2/sp3 ratio and degree of surface graphitization after treatment, especially for the H2/Ar and CO2 plasma environments. The plateau observed for longer treatment durations is likely related to a saturation of the surface dipoles generated during plasma treatment and is consistent with the surface saturation of oxygen content and C-O bonds, as demonstrated by the XPS spectra.

The decay of the IP as a function of time after completing the plasma treatment was also investigated to evaluate the temporal stability of the functional groups grafted across the graphitic planes, which can potentially be affected by atomic reconfiguration (Fig. 7). Interestingly, the time dependence of the IP was found to follow a similar pattern for all the series of plasma gases tested. Although the IP decreased for all samples over time, a steady state was reached much quicker for the H2/Ar series (14 days) than for the O2/Ar series (21 days) or the CO2 series (28 days). In particular, the base level of the WF was found to decrease over time by 0.4 eV at 30 days post-treatment for the O2/Ar reactant gas, but still remained 0.38 eV above the IP of the native CNTs. This result suggests that the remaining groups are indeed permanently attached across the graphitic walls of the CNTs. The temporal stability of the treatments is also suggesting that an extended exposure to free radicals within the plasma glow may have reached an activation energy level of the graphitic plans, above which the material may interact more strongly with oxygen from air during storage after the treatment. These activated sites, generated in larger amounts with longer treatment durations and therefore being more stochastically favorable, and may indeed react with atmospheric gases to re-assemble the surface dipoles across the CNT to their original configuration. This hypothesis would also explain why a higher amount of atomic oxygen content was produced by the H2/Ar reacted when there while neither measurable nor significant quantities of oxygen molecules were present during the plasma treatment. These results open the way to the design of specific IP materials where the surface density and coverage of functional groups across graphitic materials such as graphene or carbon nanotubes may be simply controlled through specific plasma treatments.

This study therefore provided for the first powerful insights on the stability and time decay of functional groups generated across graphitic materials. The understanding of molecular rearrangements at the nanoscale within graphene and CNT materials is critical to develop commercially viable products and optimize chemistry as advanced platforms for a range of applications.

Materials and Methods

Carbon nanotube growth and BP preparation

The CNTs were grown by chemical vapour deposition (CVD) following a previously described route66. In short, a 1–5 nm thick iron catalyst film was deposited onto a silicon substrate bearing a thin silicon dioxide layer and a mixture of helium (95 wt%) and acetylene (5 wt%) was used as the CVD feedstock for growing CNT at a temperature between 650 and 750 °C67. These CNTs typically have an outer diameter of ∼10–15 nm and a length of 150–300 μm. The CNT BP membranes were processed by vacuum filtration of CNTs dispersed in 99.8% pure propan-2-ol (Aldrich 99.9%)68. Well-dispersed CNT suspensions were obtained by repeated sonication at intervals of 15 minutes and a power of 150 W. Vacuum filtration was performed using a 47 mm diameter Millipore filtration unit attached to line vacuum (dP = −95 kPa). The CNTs were filtered onto a poly (ether sulphone) 0.2-μm pore size Millipore membrane and then peeled off to form a self-supporting membrane. The thickness of the BPs were on the order of 20+/−2 μm. All other chemicals (polydimethylsiloxane, 2-methyl imidazole, zinc nitrate hexahydrate) and gases (Analytical air, O2 in Ar, H2 in Ar, CO2) used in this study were purchased from Sigma Aldrich or BOC. The composition of the gas was 28 v% O2 in Ar, Ar and CO2 of analytical grade (purity >99.99%) or 2 v% H2 in Ar.

Surface plasma treatment conditions

Plasma treatments were performed on a PICO G plasma rig (Diener PICO PC SN 80001) in isotropic plasma generated by a High Frequency Generator at 13.56 MHz in a stainless steel chamber, represented in Figure S10. In this specific configuration, the active electrode is located near the ceiling of the breakdown chamber while the sample is placed in the lower, larger part below the electrode. Most of the high frequency electric power is absorbed in the clearance between the electrode and the top ceiling, which acts as the counter electrode. Products from the breakdown region spill into the lower part of the chamber to apply a uniform and isotropic treatment to the sample located there. The samples were treated at a fixed plasma chamber pressure of 0.2 mbar and a power of 80 W, while effects from the exposure were evaluated at several points in time in the following with regard to physical and chemical modifications occurring on the material surface. Plasma exposure durations were varied and the treatment time varied between 1 and 30 min. Changes in plasma temperature were recorded by means of a thermocouple. The temperature of the sample stage was held constant at 22 °C.

Materials characterization techniques

Scanning Electron Micrographs (SEMs) were acquired on a JEOL JSM 7800F SEM at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV and a working distance of 10 mm. The samples mounted on aluminum stubs with carbon tape were not coated prior to imaging to avoid altering their physical aspect. Transmission Electron Micrographs (TEMs) were acquired on a FEG Jeol JEM2100 Lab6 TEM at 200 kV and under high vacuum. The carbon nanotube samples were gently dispersed in iso-propanol and sonicated with a bath sonicator for 5 min to suspend the CNTs. A volume of 100 μL was then dropped onto a copper grid and the samples were left to dry in air in a contained dust free chamber overnight prior to imaging.

The ionization potential was measured using Photoelectron Spectroscopy in Air (PESA – Model AC-2). In this technique UV light is used to generate photo-electrons which ionize atmospheric oxygen molecules that are accelerated towards and open counter detector. By plotting the yield (n = 0.33 or 0.5 for semiconductor or metal materials, respectively) versus energy, the ionization energy can be determined. A UV intensity of 10 nW, UV energy between 4.2–6.2 eV with 0.1 nW step, and n = 0.5, was used. For each sample at least 3 measurements were performed on different areas and the average taken.

Raman Spectroscopy was performed with a Renishaw inVia Raman Microscope, using a 514 nm laser at 10% of the nominal power. The acquisition time was 10 s and the results were based on 3 accumulations. Measurements were conducted for each sample in at least two different spots, from which an average value was calculated and the standard deviation included in the figures as error bars. The samples were tested 1 day and 1 week post treatment to investigate temporal effects. The thermogravimetric analysis was conducted on a pristine BP by a Perkin Elmer TGA 7 Thermogravimetric Analyzer. Tests were carried out at a rate of 50 °C/min in air and the temperature was kept constant at 225 °C for 30 min in order to reproduce the plasma chamber conditions.

X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS) spectra were acquired at a pass energy of 160 eV with a 1 eV/step and a pressure in the analysis chamber of 5 × 10−9 torr with an AXIS Nova (Kratos Analytical Ltd., UK). The samples were irradiated with Al Kα radiation (hν = 1486.6 eV) from a mono-chromated source operating at 150 W. In a typical set up, the X-ray source is at 45 from the sample surface while the angle between the analyser and the sample surface is 90. The analysis was performed on 3 different spots on each sample, under the same experimental conditions. XPS spectra were evaluated with CasaXPS software in accordance with the experimental parameters. The C sp2 energy peak was calibrated at 284.5, consistent with the deconvolution of high resolution C 1s.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Merenda, A. et al. Assessing the temporal stability of surface functional groups introduced by plasma treatments on the outer shells of carbon nanotubes. Sci. Rep. 6, 31565; doi: 10.1038/srep31565 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Deakin University for funding this project through the CRGS2014 scheme. They also thank team members from Deakin University including Dr. Li He and Prof. Lingxue Kong for advice and support, Ms Chunfang Feng for help with Raman operation and Dr. Andrew Sullivan and Dr. Rosey Van Driel for advice with EM analysis. The help of Dr. Chi Huynh and Dr Stephen Hawkins (CSIRO) is also acknowledged for the growth of the CNTs. Dr. Dumée also acknowledges the support of Deakin University for his Alfred Deakin Post-Doctoral Fellowship 2015.

Footnotes

Author Contributions All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript. Author’s contributions include A.M. performed the plasma treatments, XPS, PESA and Raman tests as well as the core of the data analysis. E.D.L. performed the TEM analysis while T.C. and K.M. provided support regarding the XPS deconvolution analysis. D.C. and J.A.S. supported the work and provided guidance towards palsma treatment and impact on performance. L.F.D. performed the SEM and supported the TEM and participated to the manuscript preparation and proof-reading. All authors participated in proof-reading and manuscript preparation.

References

- Tobias G., Mendoza E. & Ballesteros B. In Encyclopedia of Nanotechnology (ed Bhushan Bharat) Ch. 48, 911–919 (Springer Netherlands, 2012).

- Hone J., Batlogg B., Benes Z., Johnson A. T. & Fischer J. E. Quantized Phonon Spectrum of Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes. Science 289, 1730–1733, 10.1126/science.289.5485.1730 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thostenson E. T., Ren Z. & Chou T.-W. Advances in the science and technology of carbon nanotubes and their composites: a review. Composites Science and Technology 61, 1899–1912, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0266-3538(01)00094-X (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Qian H., Greenhalgh E. S., Shaffer M. S. P. & Bismarck A. Carbon nanotube-based hierarchical composites: a review. Journal of Materials Chemistry 20, 4751–4762, 10.1039/C000041H (2010). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clave G. & Campidelli S. Efficient covalent functionalisation of carbon nanotubes: the use of “click chemistry”. Chemical Science 2, 1887–1896, 10.1039/C1SC00342A (2011). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J. Y. et al. Easy Preparation of Self-Assembled High-Density Buckypaper with Enhanced Mechanical Properties. Nano Letters 15, 190–197, 10.1021/nl5033588 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J. & Loo Y.-L. Effect of ozone exposure on the electrical characteristics of high-purity, large-diameter semiconducting carbon nanotubes. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 16, 10861–10865, 10.1039/C4CP00665H (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid M. H.-O. et al. Synthesis, properties, water and solute permeability of MWNT buckypapers. Journal of Membrane Science 456, 175–184, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2014.01.026 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Müller E. A., Rull L. F., Vega L. F. & Gubbins K. E. Adsorption of Water on Activated Carbons: A Molecular Simulation Study. The Journal of Physical Chemistry 100, 1189–1196, 10.1021/jp952233w (1996). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh D. H., Rance G. A., Zaka M. H., Whitby R. J. & Khlobystov A. N. Comparison of the stability of multiwalled carbon nanotube dispersions in water. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 9, 5490–5496, 10.1039/B708460A (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu A. S. & Chou T.-W. Carbon nanotube fibers for advanced composites. Materials Today 15, 302–310, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1369-7021(12)70135-9 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Guo J. et al. Influence of oxidation and distribution of carbon nanotube on mechanical properties of buckypaper/epoxy composites. Journal of Reinforced Plastics and Composites 32, 248–257, 10.1177/0731684412468799 (2013). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Liang Z., Liu T., Wang B. & Zhang C. Effective amino-functionalization of carbon nanotubes for reinforcing epoxy polymer composites. Nanotechnology 17, 1551 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boge J., Sweetman L. J., in het Panhuis M. & Ralph S. F. The effect of preparation conditions and biopolymer dispersants on the properties of SWNT buckypapers. Journal of Materials Chemistry 19, 9131–9140, 10.1039/B914824H (2009). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Gu J., Bai X., Lin L. & Zhang Y. The influence of acid treatment on multi‐walled carbon nanotubes. Pigment & Resin Technology 38, 165–173, 10.1108/03699420910957024 (2009). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Datsyuk V. et al. Chemical oxidation of multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Carbon 46, 833–840, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2008.02.012 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Ma P.-C., Siddiqui N. A., Marom G. & Kim J.-K. Dispersion and functionalization of carbon nanotubes for polymer-based nanocomposites: A review. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 41, 1345–1367, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesa.2010.07.003 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Karousis N., Tagmatarchis N. & Tasis D. Current progress on the chemical modification of carbon nanotubes. Chemical Reviews 110, 5366–5397 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltshire J. et al. Comparative studies on acid and thermal based selective purification of HiPCO produced single-walled carbon nanotubes. Chemical Physics Letters 386, 239–243 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Torres S. et al. Modification of the surface chemistry of single- and multi-walled carbon nanotubes by HNO3 and H2SO4 hydrothermal oxidation for application in direct contact membrane distillation. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 16, 12237–12250, 10.1039/C4CP00615A (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin S., Qin D., Ford W. T., Resasco D. E. & Herrera J. E. Functionalization of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes with Polystyrene via Grafting to and Grafting from Methods. Macromolecules 37, 752–757, 10.1021/ma035214q (2004). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuila B. K., Park K. & Dai L. Soluble P3HT-Grafted Carbon Nanotubes: Synthesis and Photovoltaic Application. Macromolecules 43, 6699–6705, 10.1021/ma100917p (2010). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dumée L. F. et al. Tuning the grade of graphene: Gamma ray irradiation of free-standing graphene oxide films in gaseous phase. Applied Surface Science 322, 126–135, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.10.070 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Yang D. et al. Chemical analysis of graphene oxide films after heat and chemical treatments by X-ray photoelectron and Micro-Raman spectroscopy. Carbon 47, 145–152, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2008.09.045 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. et al. N-doping of graphene through electrothermal reactions with ammonia. Science 324, 768–771 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B. et al. Preparation of polymer decorated graphene oxide by γ-ray induced graft polymerization. Nanoscale 4, 1742–1748 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Li N., Shi M., Hu Y. & Ye M. Covalent synthesis of organophilic chemically functionalized graphene sheets. Journal of colloid and interface science 348, 377–383 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. et al. UV irradiation synthesis of an Au-graphene nanocomposite with enhanced electrochemical sensing properties. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 1, 9189–9195, 10.1039/C3TA11155E (2013). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.-C., Lin C.-Y. & Chiu P.-W. Controllable graphene N-doping with ammonia plasma. Applied Physics Letters 96, 133110-133110-133113 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Reis R. et al. Amine Enrichment of Thin-Film Composite Membranes via Low Pressure Plasma Polymerization for Antimicrobial Adhesion. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 7, 14644–14653, 10.1021/acsami.5b01603 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G., Neupane S., Li W., Chen L. & Zhang J. An increase in the field emission from vertically aligned multiwalled carbon nanotubes caused by NH3 plasma treatment. Carbon 52, 468–475, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2012.09.058 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Barton D., Bradley J. W., Gibson K., Steele D. & Short R. D. An in situ comparison between VUV photon and ion energy fluxes to polymer surfaces immersed in an RF plasma. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 104, 7150–7153 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Barton D., Bradley J., Steele D. & Short R. Investigating radio frequency plasmas used for the modification of polymer surfaces. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 103, 4423–4430 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Peng J.-W. & Liu C.-H. Raman study of carbon nanotube purification using atmospheric pressure plasma. Carbon 46, 2124–2132, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2008.09.029 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B., Zhang L., Wang X. & Yang J. Surface functionalization of vertically-aligned carbon nanotube forests by radio-frequency Ar/O2 plasma. Carbon 50, 2710–2716, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2012.02.029 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Haider A.-M., Fubo R., Wen L. & Lixin D. Singular Sheet Etching of Graphene with Oxygen Plasma. Nano-Micro Letters 6, 116–124, 10.5101/nml.v6i2.p116-124 (2014). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gokus T. et al. Making graphene luminescent by oxygen plasma treatment. Acs Nano 3, 3963–3968 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guryel S. et al. Effect of structural defects and chemical functionalisation on the intrinsic mechanical properties of graphene. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 15, 659–665, 10.1039/C2CP43033A (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh G. et al. Effect of ammonia plasma treatment on graphene oxide LB monolayers. AIP Conference Proceedings 1512, 702–703, http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4791231 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Felten A., Eckmann A., Pireaux J., Krupke R. & Casiraghi C. Controlled modification of mono-and bilayer graphene in O2, H2 and CF4 plasmas. Nanotechnology 24, 355705 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy N., Nolan H., Ashok Kumar N., Hallam T. & Duesberg G. S. Functionalisation of graphene surfaces with downstream plasma treatments. Carbon 54, 283–290 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Dumée L. F. et al. Growth of nano-textured graphene coatings across highly porous stainless steel supports towards corrosion resistant coatings. Carbon 87, 395–408, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2015.02.042 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Feng C. et al. Shrinkage induced stretchable micro-wrinkled reduced graphene oxide composite with recoverable conductivity. Carbon 93, 878–886, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2015.06.011 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Antunes E. F. et al. Comparative study of first- and second-order Raman spectra of MWCNT at visible and infrared laser excitation. Carbon 44, 2202–2211, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2006.03.003 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Dresselhaus M. S., Dresselhaus G., Saito R. & Jorio A. Raman spectroscopy of carbon nanotubes. Physics Reports 409, 47–99, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2004.10.006 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Singh P. et al. Organic functionalisation and characterisation of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Chemical Society Reviews 38, 2214–2230, 10.1039/B518111A (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travessa D. N., Silva F. S. d., Cristovan F. H., Jorge A. M. Jr. & Cardoso K. R. Ag ion decoration for surface modifications of multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Materials Research 17, 687–693 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Lehman J. H., Terrones M., Mansfield E., Hurst K. E. & Meunier V. Evaluating the characteristics of multiwall carbon nanotubes. Carbon 49, 2581–2602, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2011.03.028 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Chakrapani N. et al. Spectral fingerprinting of structural defects in plasma-treated carbon nanotubes. Journal of materials research 18, 2515–2521 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Tang S., Lu N., Wang J. K., Ryu S.-K. & Choi H.-S. Novel Effects of Surface Modification on Activated Carbon Fibers Using a Low Pressure Plasma Treatment. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 111, 1820–1829, 10.1021/jp065907j (2007). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Liang B., Ogino A., Wang X. & Nagatsu M. Oxygen Functionalization of Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes by Microwave-Excited Surface-Wave Plasma Treatment. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 113, 7659–7665, 10.1021/jp9012015 (2009). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Li J. J., Shi C. S., Liu E. Z. & Zhao N. Q. Ar Plasma Modified Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes/NiFe2O4/Polyimide Nanocomposites. Advanced Materials Research 399–401, 394–398 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Okpalugo T. I. T., Papakonstantinou P., Murphy H., McLaughlin J. & Brown N. M. D. High resolution XPS characterization of chemical functionalised MWCNTs and SWCNTs. Carbon 43, 153–161, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2004.08.033 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Polaki S. R. et al. Tribological properties of chemically modified diamond like carbon films in hydrogen plasma. Tribology International 81, 283–290, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2014.09.009 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Felten A., Bittencourt C., Pireaux J. J., Van Lier G. & Charlier J. C. Radio-frequency plasma functionalization of carbon nanotubes surface O2, NH3, and CF4 treatments. Journal of Applied Physics 98, 074308, http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.2071455 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G. et al. Hydrogenation and hydrocarbonation and etching of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Journal of the American Chemical Society 128, 6026–6027 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John P. & Stoikou M. D. Hydrogen plasma interaction with (100) diamond surfaces. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 13, 11503–11510, 10.1039/C1CP20099B (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L. et al. Nanocrystalline diamond from carbon nanotubes. Applied physics letters 84, 2901–2903 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Jackson S. T. & Nuzzo R. G. Determining hybridization differences for amorphous carbon from the XPS C 1s envelope. Applied Surface Science 90, 195–203, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0169-4332(95)00079-8 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Liu L., Liu P., Sheng L. & Fan S. Plasma etching carbon nanotube arrays and the field emission properties. Diamond and Related Materials 13, 1609–1613, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.diamond.2004.01.014 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Sah C.-T. Fundamentals of solid-state electronics. (World Scientific, 1991). [Google Scholar]

- Ago H. et al. Work Functions and Surface Functional Groups of Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 103, 8116–8121, 10.1021/jp991659y (1999). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shan B. & Cho K. First principles study of work functions of single wall carbon nanotubes. Physical review letters 94, 236602 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ago H. et al. Work functions and surface functional groups of multiwall carbon nanotubes. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 103, 8116–8121 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Ryu J. Work functions of functionalized singled-walled carbon nanotubes, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Dumée L. et al. Seeded growth of ZIF-8 on the surface of carbon nanotubes towards self-supporting gas separation membranes. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 1, 9208–9214 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Dumée L. F. et al. Characterization and evaluation of carbon nanotube Bucky-Paper membranes for direct contact membrane distillation. Journal of Membrane Science 351, 36–43, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2010.01.025 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Dumée L. et al. Influence of the Sonication Temperature on the Debundling Kinetics of Carbon Nanotubes in Propan-2-ol. Nanomaterials 3, 70 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.