Abstract

The development of active, cost-effective and stable oxygen-evolving catalysts is one of the major challenges for solar-to-fuel conversion towards sustainable energy generation. Iridium oxide exhibits the best available compromise between catalytic activity and stability in acid media, but it is prohibitively expensive for large-scale applications. Therefore, preparing oxygen-evolving catalysts with lower amounts of the scarce but active and stable iridium is an attractive avenue to overcome this economical constraint. Here we report on a class of oxygen-evolving catalysts based on iridium double perovskites which contain 32 wt% less iridium than IrO2 and yet exhibit a more than threefold higher activity in acid media. According to recently suggested benchmarking criteria, the iridium double perovskites are the most active catalysts for oxygen evolution in acid media reported until now, to the best of our knowledge, and exhibit similar stability to IrO2.

Iridium oxide is an active and stable catalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction, however Ir is very rare, making it unsuitable for large-scale application. Here the authors develop a class of Ir double perovskites containing less Ir than iridium oxide, but exhibiting 3-fold higher activity in acidic media.

Iridium oxide is an active and stable catalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction, however Ir is very rare, making it unsuitable for large-scale application. Here the authors develop a class of Ir double perovskites containing less Ir than iridium oxide, but exhibiting 3-fold higher activity in acidic media.

(Photo-)electrochemical generation of fuels is a promising way to store renewable energy. However, large-scale electrochemical fuel generation is limited by the slow kinetics of the anode reaction (oxygen evolution reaction, OER)1. An active, stable and cost-effective OER catalyst compatible with the working conditions required for high-rate fuel production in polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) electrolysers is still lacking2. The best available compromise between OER activity and stability at the moment is iridium oxide IrO2 (refs 3, 4, 5), but it contains a large amount of iridium (one of the rarest elements on earth), making IrO2 unsuitable for large-scale applications. Consequently, the development of OER catalysts with smaller amounts of iridium metal is a requirement towards cost-effective multi-MW solar fuel generation using PEM electrolysers, especially in combination with iridium recycling6,7.

Complex iridium-based oxides (for example, perovskites, pyrochlores and fluorite-like compounds) are good alternatives to reduce the usage of the noble metal in the development of active and stable OER catalysts, by diluting iridium in a framework of less expensive materials. This alternative was explored by Kortenaar et al.8, who reported 12 iridium-based compounds with different crystal structures that exhibit from moderate to high OER catalytic activity in strong alkaline media (45% KOH). More recently, the group of Suntivich9 reported that the SrIrO3 simple perovskite exhibits higher OER activity than iridium oxide in alkaline media (0.1 M KOH).

Since iridium-based OER catalysts are well suited to work in the acid environment of PEM electrolysers, this work explores the versatility of complex oxides to develop a class of catalysts for the OER in acid media. We report a family of catalysts based on iridium double perovskites, which contain three times less iridium and yet exhibit a more than threefold higher activity per cm2 of real surface area (see Methods for details) for OER in acid media compared with IrO2, with similar stability. We show that these compounds are the most active catalysts for OER in acid media reported to date, to the best of our knowledge, according to recently suggested benchmarking criteria10.

Results

OER activity of the iridium-based double perovskites

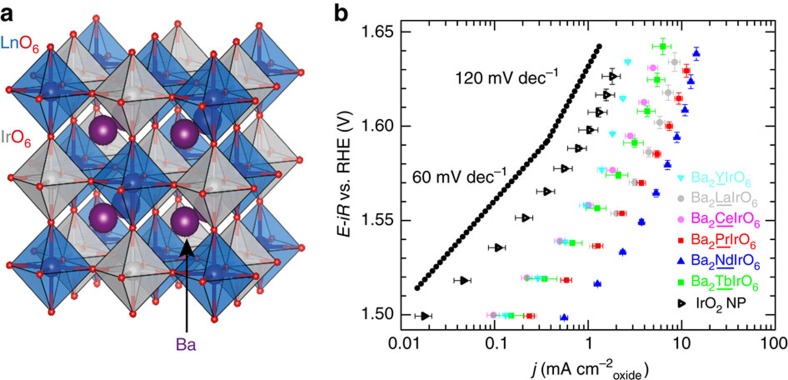

Double perovskites (DPs) are compounds with the generic formula A2BB′O6, with A denoting a large cation and B and B′ smaller cations. The crystal structure of the ideal DP is depicted schematically in Fig. 1a (ref. 11). A wide range of compounds can be prepared by different combinations of A, B and B′ cations, which allows fine tuning of the DPs. The activity (measured as the current density) towards OER in 0.1 M HClO4 (pH=1) was studied for Ba2MIrO6 DPs, with M=Y, La, Ce, Pr, Nd and Tb. The electrodes were prepared by drop-casting an ethanol-based ink of the DPs on the gold disk of a rotating ring-disk assembly and the electrochemical experiments were carried out under rotating conditions (see Methods for further details). The structure of the Ir DPs was verified by powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) and the patterns obtained agree with those reported in the literature12,13,14 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Figure 1b summarizes the measured catalytic activities in the form of Tafel plots and compares the activity with IrO2 nanoparticles that have been reported as the activity benchmark for OER in acid media10. The OER activity of the IrO2 nanoparticles compares well with the values reported previously for similar nanoparticles10,15.

Figure 1. Crystal structure and OER activity of the double perovskites.

(a) Crystal structure of a generic Ba2MIrO6 DP. (b) OER activity in 0.1 M HClO4 of Ba2MIrO6, M=Y, La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Tb, compared with the benchmark activity of IrO2 nanoparticles; the dotted lines show Tafel slopes of 60 and 120 mV per decade, to guide the eye. Measurements performed under steady-state conditions. The values in the plot are the average of three independent measurements and the error bars correspond to the s.d.

All Ir DPs show a more than threefold higher activity per cm2 of real surface area towards OER compared with the benchmarking IrO2 nanoparticles. The surface area was calculated from pseudocapacitance measurements (see Methods for details). The OER activity depends on the cation in the B-site, in the order Ce≈Tb≈Y<La≈Pr<Nd. We note that we compare the intrinsic activity of the Ir DPs and the IrO2 nanoparticles on the basis of the electrochemically active surface area. This intrinsic activity may be influenced by particle size16. Our Ir DPs are rather large (∼1 μm, see below) so it is to be expected that further activity adjustments may result from developing synthesis procedures yielding smaller particles. In addition to particle size, pH is an important parameter in activity comparisons. While Fig. 1b applies to pH=1 as we are primarily interested in the OER activity in acid media, it is well known that many oxides active for OER exhibit strongly pH-dependent reactivities17,18.

Both the IrO2 nanoparticles and the iridium-based DPs show two values for the Tafel slope, ca. 60 mV per decade between 1.5 and 1.6 V and 120 mV per decade above 1.6 V (numerical values are given in Supplementary Table 1). This feature has been reported previously for IrO2 and was explained by a change in the mechanism for OH− adsorption, which is thought to be the rate-determining step for OER on IrO2 (refs 19, 20). We note, however, that the Tafel slope measured at high potentials for Ba2YIrO6 (196+23 mV per decade) markedly deviates from the values for the other Ir DPs (ca. 120 mV per decade).

We also measured the Faradaic efficiency of Ba2PrIrO6 towards OER in 0.1 M HClO4 in a rotating ring-disk electrode (RRDE) configuration (Supplementary Fig. 2). It shows that Ba2PrIrO6 has an efficiency towards water oxidation higher than 90% at 1.50 V (η=0.27 V). The decrease in Faradaic efficiency with more anodic electrode potential is explained by the large current for OER above 1.6 V, leading to the formation of oxygen bubbles that reduce the detection efficiency on the ring.

Stability of the Ir DPs under OER conditions

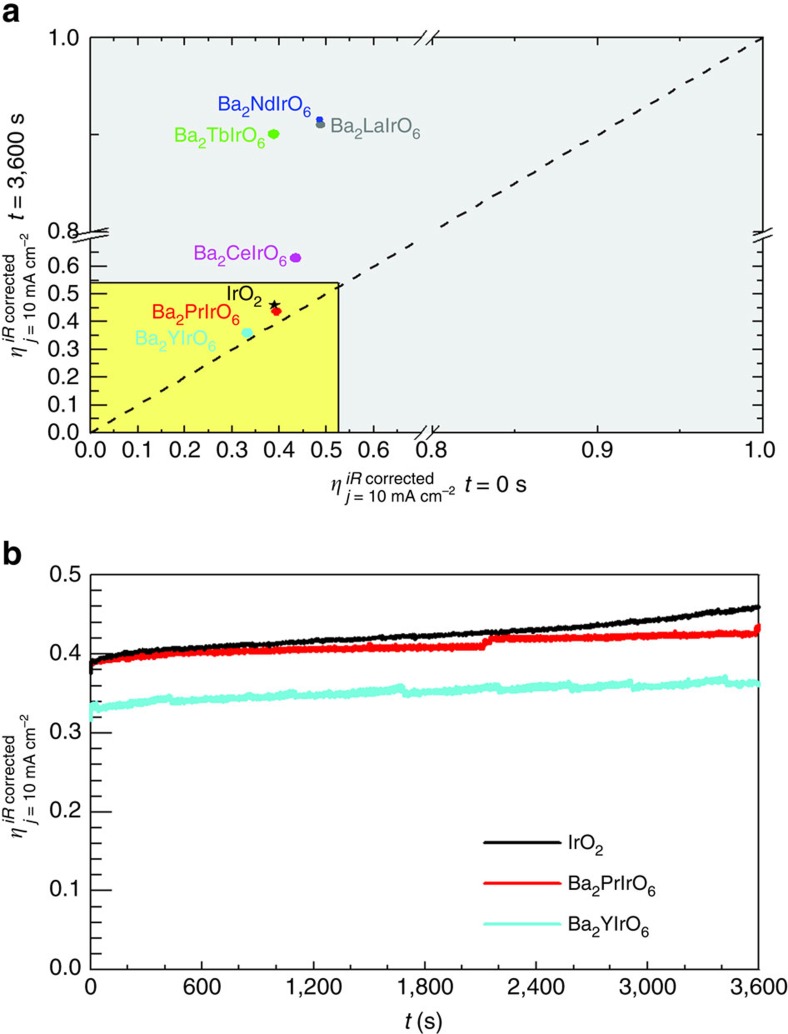

The electrochemical stability of the Ir DPs was evaluated by galvanostatic electrolysis, in a manner similar to the approach reported by the JCAP group10. Figure 2a summarizes the results obtained from these experiments. The stability of IrO2 nanoparticles is presented for comparison. The diagonal dashed line represents the expected response of a stable catalyst.

Figure 2. Stability of the double perovskites under OER conditions.

(a) OER overpotential measured on the Ir DPs after 1 h of galvanostatic electrolysis plotted as a function of the initial overpotential. (b) Evolution of the OER overpotential on Ba2PrIrO6, Ba2YIrO6 DPs and IrO2 nanoparticles during 1 h of galvanostatic electrolysis.

The results in Fig. 2a show that Ba2PrIrO6 and Ba2YIrO6 DPs are electrochemically stable on the time scale of 1 h, operating at 10 mA cm−2, and they show a very similar stability to IrO2 under the same conditions, which is the state-of-the-art catalyst for OER in acid. The electrochemical stability of these compounds is illustrated by a plot of the Ohmic-drop-corrected overpotential as a function of time during the galvanostatic electrolysis (Fig. 2b). Ba2PrIrO6 and Ba2YIrO6 in fact show better stability in terms of overpotential than the IrO2 catalyst. The La, Nd and Tb-containing DPs are also very active towards OER in acid media according to the JCAP benchmarking, but they lose their activity after 1 h of galvanostatic electrolysis (Fig. 2a). It should be realized that the JCAP stability test is not a long-term stability test as required for operation in a commercial device, demanding operation for at least 500 h at current densities higher than 1.6 A cm−2 (ref. 7). However, it provides a simple and fast method to estimate both the activity and stability of potentially promising OER catalysts without engineering-related considerations.

Due to the small amounts of material used in the OER experiments (ca. 2.5 μg), we could not obtain powder XRD after the catalytic reaction. To assess the structural stability of the Ir DPs, Ba2PrIrO6 was examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and XRD after treatment for 48 h in harsh media, namely 0.1 M HClO4 and 0.1 M HClO4+4 M H2O2. The Ba2PrIrO6 compound was selected for these experiments because it was one of the compounds that showed to be electrochemically stable (Fig. 2). The open-circuit potentials of the Ba2PrIrO6 DP in 0.1 M HClO4 solution and in 0.1 M HClO4+4 M H2O2 solution were measured to be 1.3 and 1.1 V, respectively. Therefore, the characterization of the treated powder in these two solutions should give an indication of the stability of the DP in acid at the onset of the OER. The TEM images in Supplementary Fig. 3 show that the original powder sample of Ba2PrIrO6 DP consists of rather large particles (ca. 0.5–2 μm), consistent with the sharp lines in the XRD pattern (Supplementary Fig. 1). The particle size of the Ba2PrIrO6 did not change significantly after treatment in 0.1 M HClO4 or 0.1 M HClO4+4 M H2O2 (Supplementary Fig. 3b,c) and the XRD pattern (Supplementary Fig. 4) remains virtually the same. This shows that the crystal structure of the DP is preserved during the treatment. However, there is a larger fraction of smaller particles (particle size <200 nm) in the samples that were leached compared with the pristine compound (see Supplementary Fig. 3a in comparison with Supplementary Fig. 3b,c). This suggests that Ba2PrIrO6 either cleaves or partially dissolves during the treatment but this process is slow (Supplementary Fig. 4).

We also characterized the surface composition of the pristine and treated Ba2PrIrO6 DP samples by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The results of this analysis are summarized in Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 2 in the SI. These data indicate that the surface of Ba2PrIrO6 is not stable on the acid and the oxidative treatment. XPS results show surface enrichment in iridium after both treatments of Ba2PrIrO6, whereas the barium surface contribution reduces ca. three- to fourfold with respect to the pristine compound. The surface apparently enriches in praseodymium on the oxidative treatment (0.1 M HClO4+4 M H2O2), but this is caused by the formation of a Pr2BaO4 passivation layer over the perovskite particles. For details, see the Supplementary Note 1. The XPS results show that the surface iridium sites contain a mixture of Ir(IV) and Ir(V), and become enriched in Ir(V) upon the leaching treatments (see Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Note 1).

The leaching of the components of the Ba2PrIrO6 DP during OER was also assessed by elemental analysis of the electrolyte after electrolysis experiments of 1 h at constant electrode potential (Supplementary Table 3). The post-experiment analysis indicates that ∼10 wt% of Ba and Pr leached out of the Ba2PrIrO6 DP in the potential region 1.45–1.55 V, however, a negligible amount of iridium dissolves (<1 wt%), consistent with the evidence from XPS.

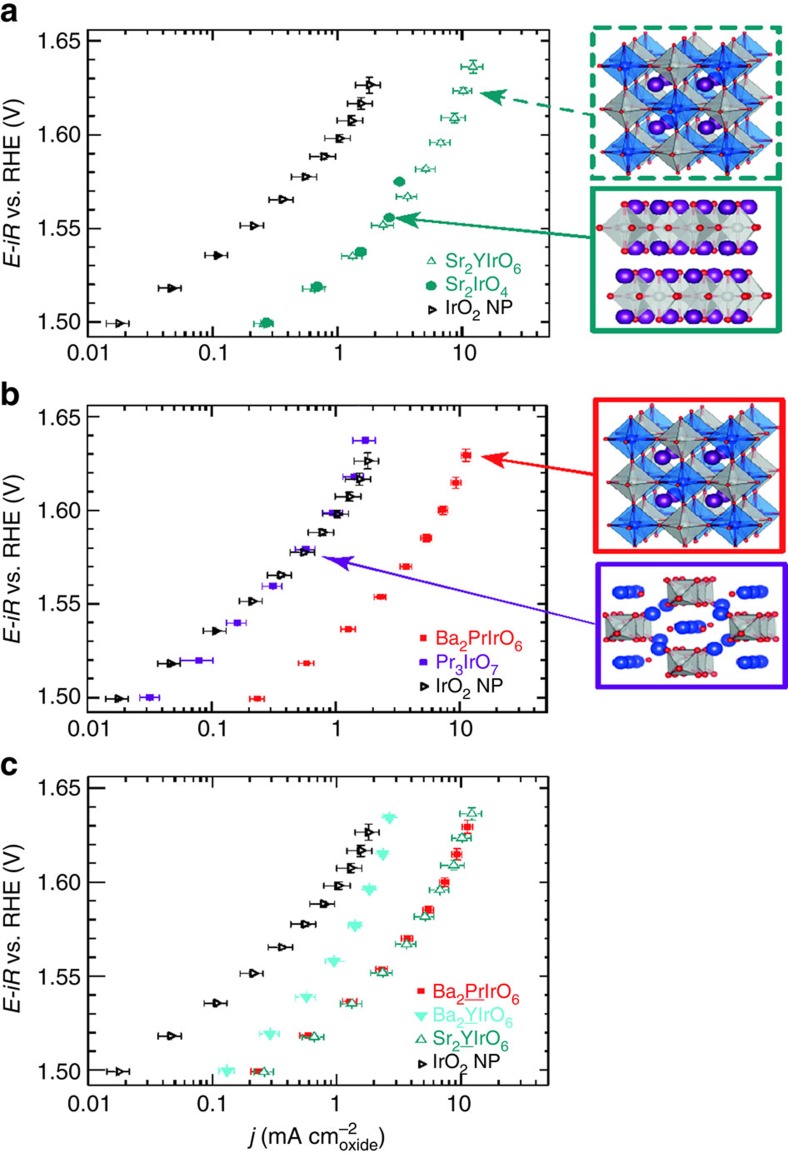

Role of the crystal structure on the OER activity of Ir DPs

The OER activity sensitively depends on the crystal structure of the iridium-based catalyst. Figure 3a,b compares the activity of the Ba2PrIrO6 and Sr2YIrO6 DPs with Sr2IrO4 and Pr3IrO7 phases (the XRD and crystal structure of the Sr2IrO4 and Pr3IrO7 phases are shown in Supplementary Fig. 7 and the XRD of the Sr2YIrO6 is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1). The activity of Sr2IrO4 is quite similar to that of Sr2YIrO6 (Fig. 3a), whereas that of Pr3IrO7 is 10-fold lower than the Ba2PrIrO6, though comparable to the activity of the IrO2 nanoparticles (Fig. 3b). The structure of Sr2IrO4 and Pr3IrO7 also contain the corner-shared IrO6 octahedra, but differ from that of the DP in the network arrangement. The Sr2IrO4 forms two-dimensional (2D) perovskite-like layers21,22, separated by a rock salt layer of SrO (Supplementary Fig. 7a), whereas in Pr3IrO7 the IrO6 octahedra are linked by sharing the corner oxygen and form one-dimensional (1D) chains23 (Supplementary Fig. 7b). It is important to note that Sr2IrO4 is very unstable under the OER measuring conditions, and its activity abruptly decreases above 1.6 V due to decomposition, hence its OER activity in Fig. 3a is shown until ca. 1.58 V. This illustrates that the 2D arrangement of IrO6 octahedra is the minimum condition required for the enhanced OER activity but that the activity and stability of the Ir DPs is linked with the 3D perovskite arrangement.

Figure 3. Structure sensitivity of the OER activity on the double perovskites.

(a) OER activity in 0.1 M HClO4 of Sr2YIrO6 DP in comparison with Sr2IrO4. (b) OER activity in 0.1 M HClO4 of Ba2PrIrO6 DP in comparison with Pr3IrO7. (c) Effect of the A and B′ cation substitution on the OER activity in 0.1 M HClO4 of the Ir DPs. The benchmark activity of IrO2 nanoparticles is shown for comparison. Measurements performed under steady-state conditions. The values in the plot are the average of three independent measurements and the error bars correspond to the s.d.

Discussion

Regarding the high activity measured for the Ir DPs, we postulate that the crystal lattice strain caused by the small lanthanide and yttrium cations in the B′ site of the DPs may be related to the enhanced OER activity measured in these compounds. DFT calculations have shown that the substitution for small(er) A-site cations can decrease oxygen adsorption energies on simple perovskites (ABO3), due to the crystal strain24. Since IrO2 has been reported to bind oxygen too strongly for a truly optimal catalyst25,26, the lattice strain caused by substitution of smaller lanthanides or yttrium could weaken the oxygen adsorption energy and therefore improve the activity of the Ir DPs in comparison with IrO2. The effect of strain in the crystal lattice on OER activity of the Ir DPs was further confirmed by comparing the activity measured for Ba2YIrO6 and Sr2YIrO6 (Fig. 3c), showing the enhancing effect of the smaller strontium cation on the Ir DP with respect to its barium analogue, in agreement with the computational evidence reported for simple perovskites. The activity of Ba2CeIrO6 shows an additional effect related to the IrIV centres12,13; this increases the binding energy of adsorbates24 and may explain why this DP is the least active in the series. We speculate that the superior performance of these materials is due to the perovskite-like network optimizing the orbital interaction between the B,B′ cations and O2−, and allowing adjustment of the B–O and B′–O bond distances to accommodate local charge changes. Since the binding of the OER intermediates requires the iridium centres to adjust their charges, the breathing mode displacement of oxygen in the perovskite-like network would favour lattice adjustments that do not exist in the rutile structure (IrO2) or in fluorite-like compounds. In addition, the observed surface leaching may also contribute to the enhancement of the OER activity of the perovskite surface by leaving behind highly active iridium centres.

In summary, we have reported a family of Ir DPs electrocatalysts with superior activity for water oxidation in acid media. Compared with IrO2, the state-of-the art benchmarking catalyst, these compounds contain 32 wt% less iridium and exhibit higher activity per real surface area and similar stability for the OER. Our results show that a 3D network of corner-shared octahedra is a necessary prerequisite for the activity enhancement of the Ir DPs as well as for their chemical stability under anodic working conditions. Our findings regarding the effect of the B-site cation on the catalysis towards OER of the Ir DPs suggest that the activity of these compounds might be further improved by carefully selecting the A- and B-site cations. Our strategy for thrifting iridium usage could also be extended to modulate the activity and stability of ruthenium-containing compounds, with a lower content of ruthenium compared with ruthenium oxide.

Methods

Chemicals

The water used to prepare solutions and clean glassware was deionized and ultrafiltrated with a Millipore Milli-Q system (resistivity=18.2 MΩ·cm and TOC<5 p.p.b.). All chemicals used in this work were of high purity (pro analysis grade or superior) and they were used without any further purification. The perchloric acid used for the electrolyte was from Merck (70–72%, EMSURE).

Synthesis and characterization of the iridium-based catalysts

Ba2MIrO6 (M=La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Tb and Y) double perovskites were prepared from BaCO3, SrCO3, La2O3, CeO2, Pr6O11, Nd2O3, Tb4O7, Y2O3 and metallic iridium powder, respectively, in alumina crucibles, using the standard solid-state reactions described in literature13,14,22,23. All reactions were carried out in air and the products were furnace-cooled to room temperature. The powders were intermittently reground during the synthesis.

The suspension of iridium oxide nanoparticles was prepared by acid-catalysed condensation of [Ir(OH)6]2− intermediate obtained from alkaline hydrolysis of Na2IrCl6 at 90 °C (ref. 27).

X-ray powder diffraction patterns were collected on a Philips X'Pert diffractometer, equipped with the X'Celerator, using Cu-Kα radiation in steps of 0.020°(2θ) with 10 s counting time in the range 10°<2θ<100°.

Electrochemical experiments

Glassware was cleaned by boiling in a 3:1 mixture of concentrated sulfuric acid and nitric acid to remove organic contaminants, after which it was boiled five times in water. When not in use, the glassware was stored in a solution of 0.5 M H2SO4 and 1 g l−1 KMnO4. To clean the glassware from permanganate solution, it was rinsed thoroughly with water and then immersed in a diluted solution of H2SO4 and H2O2 to remove MnO2 particles, after which it was rinsed with water again and boiled five times in ultrapure water.

The electrochemical experiments were carried out at room temperature in a two-compartment electrochemical cell with the reference electrode separated by a Luggin capillary. Measurements were performed using a homemade rotating Pt ring–Au disk electrode (φdisk=4.6 mm) as working electrode, a gold spiral as counter electrode and a reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) as reference electrode; a platinum wire was connected to the reference electrode through a capacitor of 10 μF, acting as a low-pass filter to reduce the noise in the low-current experiments. The electrochemical experiments were controlled with a potentiostat/galvanostat (PGSTAT12, Metrohm-Autolab) and they were performed either with cyclic voltammetry at 0.01 V s−1 or with potentiostatic steps of 0.02 V every 30 s. The latter procedure is referred to as steady-state measurements. Before and between experiments, the working electrode was polished with 0.3 and 0.05 μm alumina paste (Buehler Limited), subsequently it was sonicated in water for 5 min to remove polishing particles. The electrolyte was saturated with air prior to the experiments by bubbling for 20 min with compressed air, with the air first passed through a 6 M KOH washing solution. The RRDE experiments to measure the Faradaic efficiency were carried out with the electrolyte saturated with argon, which was purged through for at least 30 min prior to the experiment and kept passing above the solution during the measurement. For RRDE measurements, the Pt ring was kept at 0.45 V versus RHE while the disk with the catalyst loaded was scanned at 0.01 V s−1 in the potential range 1.25–1.75 V versus RHE. The efficiency (η) was calculated with equation (1), assuming that the oxygen reduction proceeds via four electron transfer, to produce water:

|

The collection factor (N) for oxygen was measured by using IrO2 as reference catalyst, and the value obtained was 0.199+0.001, which corresponds well with the value obtained from experiments with the redox couple [Fe(CN)6]3−/[Fe(CN)6]4− (N=0.23); the small difference has been attributed to the non-ideal outward flow of O2 (ref. 15).

The catalysts were immobilized on the Au disk by drop-casting an ethanol-based ink of the oxides, using Na-exchanged neutral Nafion as binder28. The inks were prepared to yield the following final concentrations: 1 mgoxide/mLink and 0.7 mgNafion/mLink (ref. 29). Prior to the preparation, the powders were ground in a mortar to eliminate big clusters. The appropriate amount of ink was drop-cast on the electrode to obtain 15 μgoxide cmdisk−2 of loading and this electrode was dried in vacuum; cmdisk2 refers to the geometrical surface area of the Au disk.

The current densities reported in this work were calculated using the electrochemical surface area (addressed as real surface area) obtained from pseudo-capacitance measurements, assuming 60 μF cm−2 for the specific capacitance of the double layer10,30. This procedure of surface area determination was preferred over the Brunauer–Emmet–Teller (BET) method, based on the physical absorption of a gas on the oxide surface, because it allowed us to estimate the active electrochemical surface area in contrast to the surface area obtained from BET measurements30. The Tafel plots were corrected for the Ohmic resistance of the electrolyte, the resistance was measured by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and by conductimetry10 and the value obtained was 24±1 Ω.

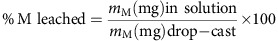

The amount of dissolved components from the Ba2PrIrO6 after electrochemical water oxidation experiments in 0.1 M HClO4 was by means of inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES). These experiments were performed potentiostatically (1 h electrolysis) and in non-rotating conditions, using 10 ml of electrolyte. The double perovskite catalyst was drop-cast on a gold disk (950 μgoxide cmdisk−2 of Ba2PrIrO6), using an ethanol-based ink similar to the one described for the RRDE experiments but with higher perovskite content (30 mgoxide/mLink). The electrolyte was analysed directly in a Varian Vista-MPX CCD Simultaneous ICP-AES. The fraction of dissolved metal (% M leached) was calculated as follows:

|

In this equation, mM (mg)in solution was obtained from the ICP-AES analysis after the electrolysis experiment and mM (mg)drop-cast corresponds to the mass of each component of the Ba2PrIrO6 double perovskite, calculated from its stoichiometry.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the authors upon request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Diaz-Morales, O. et al. Iridium-based double perovskites for efficient water oxidation in acid media. Nat. Commun. 7:12363 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12363 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-7, Supplementary Tables 1-3, Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary References.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) and in part within by the research programme of BioSolar Cells, co-financed by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs, Agriculture and Innovation.

Footnotes

Author contributions M.T.M.K. and O.D.M. designed the experiments. W.T.F. and S.R. made the DPs synthesis and the XRD characterization. R.K. and P.K performed the TEM characterization. T.W. and J.G. performed the XPS characterization. O.D.M. and S.R. performed the electrochemical experiments. O.D.M. and M.T.M.K. wrote the manuscript and all authors edited the manuscript.

References

- Koper M. T. M. Thermodynamic theory of multi-electron transfer reactions: implications for electrocatalysis. J. Electroanal. Chem. 660, 254–260 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Turner J. et al. Renewable hydrogen production. Int. J. Energy Res. 32, 379–407 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Cherevko S. et al. Dissolution of noble metals during oxygen evolution in acidic media. ChemCatChem 6, 2219–2223 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Cherevko S. et al. Stability of nanostructured iridium oxide electrocatalysts during oxygen evolution reaction in acidic environment. Electrochem. Commun. 48, 81–85 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Danilovic N. et al. Activity-stability trends for the oxygen evolution reaction on monometallic oxides in acidic environments. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 2474–2478 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner J. A. Sustainable hydrogen production. Science 305, 972–974 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Energy. Hydrogen and Fuell Cells Program. 2015 Annual Progress Report. Section II.B.3. Low-Noble-Metal-Content Catalysts/Electrodes for Hydrogen Production by Water Electrolysis. Available at http://www.hydrogen.energy.gov/pdfs/progress15/ii_b_3_ayers_2015.pdf accesed on December 2015.

- ten Kortenaar M. V., Vente J. F., IJdo D. J. W., Müller S. & Kötz R. Oxygen evolution and reduction on iridium oxide compounds. J. Power Sources 56, 51–60 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Tang R. et al. Oxygen evolution reaction electrocatalysis on SrIrO3 grown using molecular beam epitaxy. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 6831–6836 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- McCrory C. C., Jung S., Peters J. C. & Jaramillo T. F. Benchmarking heterogeneous electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 16977–16987 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard C. J. & Stokes H. T. Structures and phase transitions in perovskites—a group-theoretical approach. Acta Crystallogr. A 61, 93–111 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeshima M., Harada D. & Hinatsu Y. Crystal structures and magnetic properties of ordered perovskites BaLnIrO (Ln=lanthanide). J. Mater. Chem. 10, 419–422 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Fu W. T. & IJdo D. J. W. On the space group of the double perovskite Ba2PrIrO6. J. Solid State Chem. 178, 1312–1316 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Fu W. T. & IJdo D. J. W. Re-examination of the structure of Ba2MIrO6 (M=La, Y): space group revised. J. Alloys Compd. 394, L5–L8 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Suntivich J., May K. J., Perry E. E. & Shao-Horn Y. Synthesis and activities of rutile IrO2 and RuO2 nanoparticles for oxygen evolution in acid and alkaline solutions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 399–404 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsounaros I., Cherevko S., Zeradjanin A. R. & Mayrhofer K. J. J. Oxygen electrochemistry as a cornerstone for sustainable energy conversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 102–121 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano L. et al. pH dependence of OER activity of oxides: current and future perspectives. Catal. Today 262, 2–10 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Morales O., Ferrus-Suspedra D. & Koper M. T. M. The importance of nickel oxyhydroxide deprotonation on its activity towards electrochemical water oxidation. Chem. Sci. 7, 2639–2645 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J.-M., Zhang J.-Q. & Cao C.-N. Oxygen evolution reaction on IrO2-based DSA type electrodes: kinetics analysis of Tafel lines and EIS. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 29, 791–797 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Dau H. et al. The mechanism of water oxidation: from electrolysis via homogeneous to biological catalysis. ChemCatChem 2, 724–761 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Beznosikov B. V. & Aleksandrov K. S. Perovskite-like crystals of the Ruddlesden-Popper series. Crystallogr. Rep. 45, 792–798 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q. et al. Neutron powder diffraction study of the crystal structures of Sr2RuO4 and Sr2IrO4 at room temperature and at 10 K. J. Solid State Chem. 112, 355–361 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Vente J. F. & IJdo D. J. W. The orthorhombic fluorite related compounds Ln3IrO7. Mater. Res. Bull. 26, 1255–1262 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Calle-Vallejo F. et al. Number of outer electrons as descriptor for adsorption processes on transition metals and their oxides. Chem. Sci. 4, 1245–1249 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Rossmeisl J., Qu Z. W., Zhu H., Kroes G. J. & Nørskov J. K. Electrolysis of water on oxide surfaces. J. Electroanal. Chem. 607, 83–89 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Man I. C. et al. Universality in oxygen evolution electrocatalysis on oxide surfaces. ChemCatChem 3, 1159–1165 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Hernandez-Pagan E. A., Vargas-Barbosa N. M., Dysart J. L. & Mallouk T. E. A high yield synthesis of ligand-free iridium oxide nanoparticles with high electrocatalytic activity. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2, 402–406 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Morales O., Hersbach T. J. P., Hetterscheid D. G. H., Reek J. N. H. & Koper M. T. M. Electrochemical and spectroelectrochemical characterization of an iridium-based molecular catalyst for water splitting: turnover frequencies, stability, and electrolyte effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 10432–10439 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suntivich J., Gasteiger H. A., Yabuuchi N. & Shao-Horn Y. Electrocatalytic measurement methodology of oxide catalysts using a thin-film rotating disk electrode. J. Electrochem. Soc. 157, B1263–B1268 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Trasatti S. & Petrii O. A. Real surface area measurements in electrochemistry. J. Electroanal. Chem. 327, 353–376 (1992). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-7, Supplementary Tables 1-3, Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary References.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are available from the authors upon request.