Summary

Leptospira are unique among bacteria based on their helical cell morphology with hook-shaped ends and the presence of periplasmic flagella (PF) with pronounced spontaneous supercoiling. The factors that provoke such supercoiling, as well as the role that PF coiling plays in generating the characteristic hook-end cell morphology and motility, have not been elucidated. We have now identified an abundant protein from the pathogen L. interrogans, exposed on the PF surface, and named it Flagellar-coiling protein A (FcpA). The gene encoding FcpA is highly conserved among Leptospira and was not found in other bacteria. fcpA- mutants, obtained from clinical isolates or by allelic exchange, had relatively straight, smaller-diameter PF, and were not able to produce translational motility. These mutants lost their ability to cause disease in the standard hamster model of leptospirosis. Complementation of fcpA restored the wild-type morphology, motility and virulence phenotypes. In summary, we identified a novel Leptospira 36-kDa protein, the main component of the spirochete's PF sheath, and a key determinant of the flagella's coiled structure. FcpA is essential for bacterial translational motility and to enable the spirochete to penetrate the host, traverse tissue barriers, disseminate to cause systemic infection, and reach target organs.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Leptospirosis is the major zoonotic cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide (Costa et al., 2015). The disease can be caused by >200 serovars distributed among ten pathogenic species that belong to the genus Leptospira, which also encompasses saprophytic and intermediate species (Ko et al., 2009). A key feature of pathogenic Leptospira is their ability to produce rapid translational motility (Noguchi, 1917). Pathogenic Leptospira rapidly penetrate abraded skin and mucous membranes, traverse tissue barriers and cause a systemic infection within minutes to hours (McBride et al., 2005, Ko et al., 2009, Bharti et al., 2003). Motile spirochetes rely on their helical or flat wave morphology and asymmetrical rotation of periplasmic flagella (PF) attached near each cell cylinder extremity to generate translational motility (Charon & Goldstein, 2002, Charon et al., 2012, Motaleb et al., 2000). However, leptospiral morphology is markedly different from what is observed for other spirochetes. Leptospires are unique as they have hook-shaped cell ends when PF are not rotating and cells thus resemble to a question mark, a feature initially observed by Stimson in 1907, who named the organism Spirocheta (now Leptospira) interrogans (Stimson, 1907). During translational motility, as viewed from the center of the cell, counterclockwise PF rotation produces spiral-shaped ends at the leading end, while concomitantly clockwise PF rotation causes the gyrating cell to remain hook-shaped at the tail end (Berg et al., 1978, Kan & Wolgemuth, 2007, Goldstein & Charon, 1990, Nakamura et al., 2014).

Spirochete PF are similar in structure and function to flagella of externally flagellated bacteria, as each consists of a basal body complex or motor, a flexible hook and a flagellar filament (Charon & Goldstein, 2002, Limberger, 2004). Whereas PF from non-Leptospira spirochetes display curved forms when viewed by electron microscopy once purified (Charon et al., 1991, Li et al., 2000a), leptospire PF are instead extensively supercoiled in the form of a spring (Berg et al., 1978, Bromley & Charon, 1979, Wolgemuth et al., 2006, Kan & Wolgemuth, 2007). Furthermore, leptospire mutants that form uncoiled PF, or lacking PF altogether, maintain their helical cell body shape but display straight cell axes, and are also unable to generate translational motility (Bromley & Charon, 1979, Picardeau et al., 2001). These findings, taken together, suggest that the coiled phenotype of PF and their interaction with the helical cell cylinder are key determinants in producing the peculiar cell morphology observed for leptospires and their ability to produce translational motility.

The molecular factors that contribute to the coiled flagella phenotype in Leptospira have not been fully unveiled. In contrast to the flagellar filaments of enterobacteria, which are composed of a single flagellin protein (Macnab, 1996, Berg, 2003), spirochete PF are a multi-protein complex that comprise of a core, composed of the FlaB family of flagellin-like proteins, and sheath proteins (Charon & Goldstein, 2002, Wolgemuth et al., 2006, Li et al., 2000b). Although FlaA, a protein family conserved across spirochetes (Wolgemuth et al., 2006, Li et al., 2000b, Charon & Goldstein, 2002, Liu et al., 2010, Li et al., 2008), was found to form a flagellar sheath for Brachyspira hyodysenteriae (Li et al., 2000a), Treponema pallidum (Cockayne et al., 1987, Isaacs et al., 1989) and Spirochaeta aurantia (Brahamsha & Greenberg, 1989) this observation was not confirmed for Borrelia burgdorferi (Motaleb et al., 2004) and L. interrogans (Lambert et al., 2012). Spirochetes appear thus to differ in the composition and organization of their flagella. Elucidation of the complex structure of leptospire PF may reveal new mechanisms for flagella-associated motility. Although recent advances have been made to genetically manipulate Leptospira and address this question (Picardeau, 2015), the leptospire PF structure remains poorly characterized.

Herein, we report our investigation of motility-deficient and motile strains from a clinical isolate of L. interrogans, which in turn led to the identification of a novel and highly abundant leptospire protein, Flagellar-coiling protein A (FcpA). Targeted mutagenesis and complementation, together with immuno-electron microscopy, demonstrated that FcpA is a key component of leptospiral PF sheath and is an essential requirement for the hook-shaped morphology of the cell ends, coiled flagella phenotype and translational motility. We also provide evidence that these features are essential for the process of bacterial penetration and dissemination in host tissues.

Results

Isolation of a motility-deficient clone in L. interrogans

L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain Fiocruz LV2756 was isolated from a Brazilian patient with pulmonary hemorrhage syndrome due to leptospirosis (Gouveia et al., 2008). Two colony morphologies, large and small, were observed after plating the isolate onto solid EMJH media. The phenotype was confirmed by measuring the ability of the cells to grow in motility plate assays (Fig. 1A), confirming the previous observation. Sub-culturing of larger colonies yielded leptospires, which had phenotypes similar to wild-type (WT) L. interrogans with respect to the characteristic hook-end cell morphology (Figs. 1B and 1C) and translational motility (Video S1). In contrast, sub-cultures of small colonies yielded leptospires that lacked the terminal hook-ends (Figs. 1B and 1C), and did not produce translational motility (Video S2). Leptospires from small colonies retained the characteristic corkscrew cell body morphology, were able to gyrate their ends, forming spiral waveforms at their terminal ends. We also observed that a proportion of these leptospires grew as long chains with incomplete division planes (Video S2). Sub-cultures of large and small colonies were named motile and motility-deficient strains, respectively.

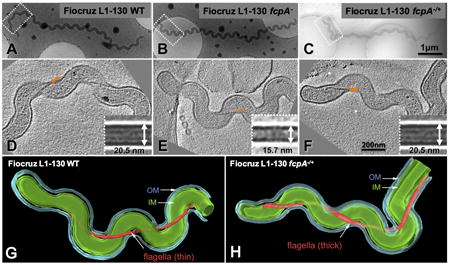

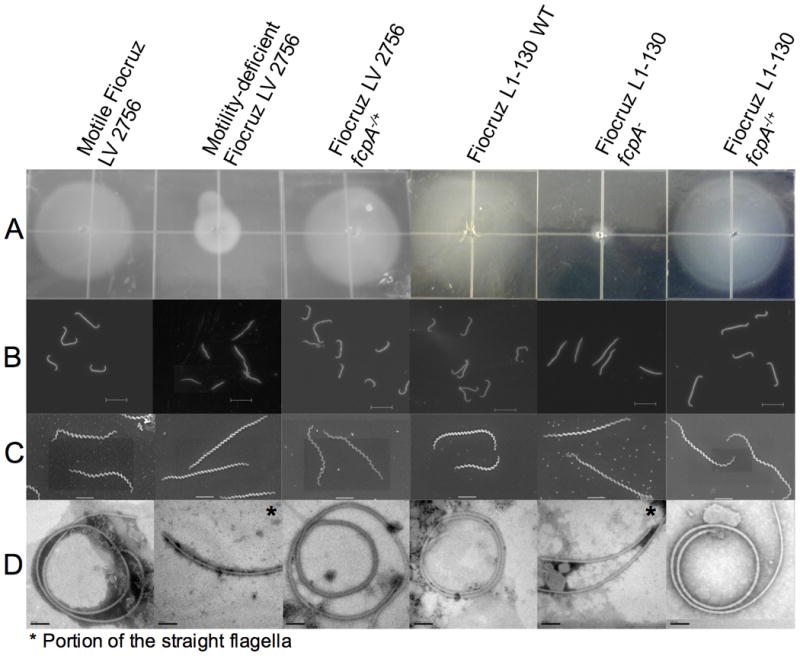

Figure 1. Phenotypes of WT, fcpA- mutant and complemented L. interrogans strains.

(A) Motility assay for which 105 bacteria were inoculated on 0.5% agarose plates [each square, 1 cm2] and incubated for 10 days at 29°C; (B) Dark-field microscopy [bar=10μm]; (C) Scanning electron microscopy [bar=2μm]; and (D) Transmission electron microscopy of negatively stained, purified periplasmic flagella [bar=100nm]. Motility-deficient Fiocruz LV2756 strain was isolated from a clinical isolate. Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA- strain was generated by allelic exchange and complemented strains Fiocruz LV2756 fcpA-/+ and Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA-/+ were obtained by reintroducing the fcpA gene. See also Videos S1-S6.

Velocity measurements of both strains showed a statistically significant decrease of the mean velocity for the motility-deficient strain (2.77 ± 1.7μm/s) when compared with the motile strain cells (11.4 ± 4.47μm/s, p<0.0001) (Fig. S2A). The path of individuals cells shows that the Fiocruz LV2756 motility-deficient strain lacks translational motility, indicating that the residual velocity measured most-likely derives from gyration-related movement combined with Brownian motion (Fig. S2B). Transmission electron microscopy of purified negatively stained PF revealed that the motility-deficient strain had straightened PF, opposed to the extensively coiled PF observed from the motile strain and WT strains (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, diameters of PF from motility-deficient strain (mean 16.3 ± 2.9 nm) were significantly smaller than those from motile strain (mean 21.5 ± 2.2 nm, p <0.0001). However, there was no difference in the length of the flagella between motile strain (2.14 ± 0.57μm) and motility-deficient strain (2.17 ± 0.52μm, p=0.8870). Taken together, these data suggest that the alteration of the morphology of the flagellum is responsible for the loss of hook-shaped ends in the motility-deficient strain.

Motility is required for host penetration and virulence

Intraperitoneal inoculation of hamsters with motile strain uniformly induced a moribund state between 6-8 days post-infection (Table 1). In contrast, hamsters infected with motility-deficient strain had significantly (p<0.05) reduced mortality and prolonged survival. Loss of the fcpA gene was associated with a greater than seven log increase (4.64 to ≥108 bacteria) in the LD50, indicating that motility is an essential determinant for virulence (Table S1).

Table 1. Virulence of wild-type, fcpA- mutant and complemented strains of Leptospira interrogans in the hamster model of leptospirosis*.

| Strains | Mortality (%) | Time to death (days) |

|---|---|---|

| Motile Fiocruz LV2756 | 100 | 6,6,6,6,6,6,6,8 |

| Motility-deficient Fiocruz LV2756 | 0¶ | -¶ |

| Fiocruz LV2756 fcpA-/+§ | 100❖ | 6,6,8,8,9,9,10,10❖ |

| Fiocruz L1-130 WT | 100 | 6,6,6,8,8,8,8,8 |

| Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA- | 0¶⌘ | -¶ |

| Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA-/+ § | 100❖ | 6,6,6,8,8,8,8,8❖ |

Results are shown for one representative experiment among a total of three, which were performed. Groups of 8 animals were inoculated intraperitoneally with 108 bacteria for each strain and then followed for 21 days.

Mortality and survival was significantly (p<0.0001) decreased and increased, respectively, compared with motile Fiocruz LV2756 and Fiocruz L1-130 strains.

Strains were genetically complemented with fcpA gene.

Mortality and survival was significantly (p<0.0001) increased and decreased, respectively, compared with motility-deficient Fiocruz LV2756 and Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA- strains.

Mortality was 37.5% in one of the three experiments but was significantly lower (p=0.026) than the mortality (100%) for hamsters infected with the Fiocruz L1-130 strain.

To determine whether the loss of virulence observed for the motility-deficient mutant was due to a defect in its ability to disseminate in the host, we performed quantitative PCR analysis of tissues from animals that were infected intraperitoneally with motile and motility-deficient strains and perfused prior to harvesting. One hour after inoculation, the motile strain was detected at >103 genome equivalents (GEq) per gram in tissues, including immune privileged sites such as the eye (Fig. 2A). Four days after inoculation, bacterial loads reached >107 GEq per gram in blood, lung, liver and kidneys (Fig. 2B). Infection with the motility-deficient strain did not yield detectable bacteria in tissue one hour after infection but did produce bacterial loads of up to 104 GEq per gram in tissues obtained four days after challenge, indicating that the motility-deficient strain was able to disseminate from the peritoneum, cause a systemic infection and reach organs, although at a low burden when compared with the motile strain (Figs. 2A and 2B). Bacteria were not detected in tissues 21 days after infection (data not shown), indicating that infection with the motility-deficient strain was transient.

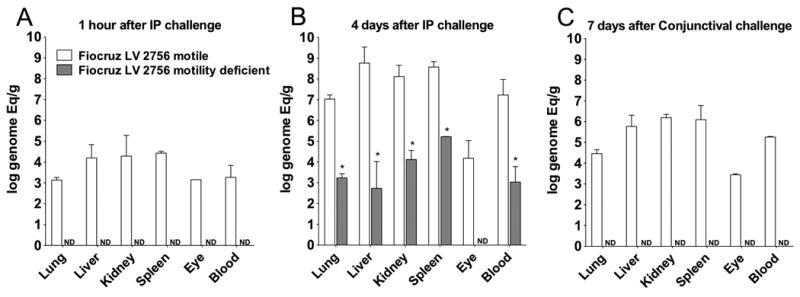

Figure 2. Dissemination of motile and motility-deficient Leptospira interrogans strains during hamster infection.

Hamsters were inoculated with 108 bacteria of the motile (white columns) and motility-deficient (gray columns) strains by intraperitoneal (A and B) or conjunctival (C) routes. Quantitative PCR analysis was performed on blood and tissues harvested one (A) and four (B) days after intraperitoneal inoculation and 7 days (C) after conjunctival inoculation. Geometric mean values and standard deviations are shown for genome equivalents of leptospiral DNA per ml of blood and gram of tissue, which were obtained in two independent experiments. Leptospiral DNA load for the motile strain was significantly (p<0.0001) higher than the motility-deficient strain for all tissues and time points. ND, not detected. See also Fig. S1.

We then determined whether the motility-deficient strain was capable of penetrating epithelial barriers and entering the host, the key initial step in infection. Inoculation of hamsters with 108 bacteria of motile strain via conjunctival route produced bacteremia and bacterial loads of >105 GEq per gram in tissues collected seven days post-infection and uniformly caused death at 8-9 days post-infection (Fig. 2C). In contrast, inoculation with the motility-deficient strain did not yield detectable bacteria in tissues or produce a lethal infection. Furthermore, we found that motility-deficient strain was unable to translocate in vitro across polarized MDCK cell monolayers, in contrast to WT strain (Fig. S1).

Identification of a novel Leptospira flagellar-associated protein

SDS-PAGE analysis identified a prominent band with a molecular weight of 36kDa in whole cell lysates (data not shown) and purified PF (Fig. 3A, lane 1) of the motile strain, which was absent in preparations of the motility-deficient strain (Fig. 3A, lane 2). Mass spectrometry (MS) of this 36-kDa protein excised from the gel band identified 10 unique peptides, which were associated with the motile strain and not the motility-deficient strain. Peptide sequences were identical and covered 83% of the predicted hypothetical protein LIC13166 of L. interrogans strain Fiocruz L1-130, a virulent strain (Ko et al., 1999) whose genome was previously sequenced (Nascimento et al., 2004).

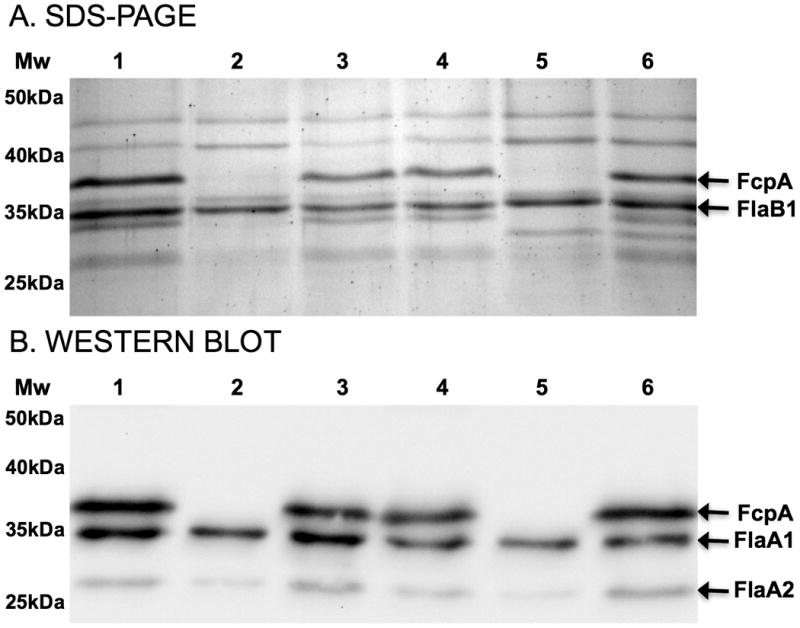

Figure 3. Expression of FcpA protein in purified periplasmic flagella of WT, fcpA- mutant and complemented L. interrogans strains.

(A) Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE of purified flagella from motile Fiocruz LV2756 [lane 1], motility-deficient Fiocruz LV2756 [lane 2], Fiocruz LV2756 fcpA-/+ [lane 3], WT Fiocruz L1-130 [lane 4], Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA- [lane 5], and Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA-/+ [lane 6] strains. In Fig. 3A, arrows indicate the position of FcpA and FlaB1 proteins, which were identified by mass spectroscopy. (B) Immunoblotting analysis of purified flagella incubated with a mixture of polyclonal antibodies against FcpA and control antibodies against flagella-associated proteins, FlaA1 and FlaA2. Arrows indicate the positions of these three proteins in Fig. 3B.

All of the Leptospira genomes present in public databases (>500 at the time of writing) have orthologs of the gene lic13166. However, no orthologs were identified in the genome of other spirochetes or any other bacterial species. The amino acid sequence identity between LIC13166 orthologs of pathogenic, intermediate and saprophytic species of Leptospira was 95-100%, 88% and 76-79%, respectively. LIC13166 is predicted to encode a protein of 306 amino acids, of which the first 25 encode a signal peptide. A previous study reported that the LIC13166 gene product was the 13th most abundant among all cell proteins in L. interrogans (Malmstrom et al., 2009). Polyclonal antibodies to recombinant LIC13166 protein recognized a 36kDa protein in whole-cell lysates (data not shown) and purified PF (Fig. 3B, lane 1) of the motile strain and did not label moieties in western-blot of the motility-deficient strain (data not shown) or its purified PF (Fig. 3B, lane 2). Since the LIC13166 protein was specifically associated with coiled PF and not straight PF, we named the protein, Flagellar-coiling protein 1 (FcpA).

Further analysis of SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3A) also revealed the presence of a band below FlaB1 in the motile strain (Fig. 3A line 1), which is absent on the motility-deficient strain (Fig. 3A line 2). This uncharacterized protein could correspond to a FcpA-associated protein of the flagellum. Furthermore, quantitative immunoblotting showed that there was a reduction of expression of both FlaA1 (26% ± 2.9) and FlaA2 (57.5% ± 3.3) proteins in the motility-deficient strain, but no significant reduction of FlaB1 (98.2% ± 2.4). Together, these observations indicate that the lack of FcpA protein modify the composition of proteins in the flagellum.

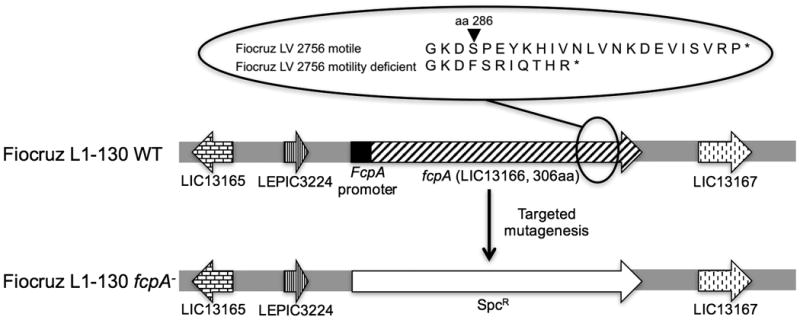

The fcpA gene from the motility-deficient strain had an insertion of a deoxythymidine at base pair position 855, which introduced a frame shift at amino acid position 286 and resulted in a premature stop codon at amino acid position 294 (Fig. 4). In contrast, the fcpA gene sequence from the motile strain was identical to WT strain. Whole genome sequencing of motile (NCBI accession number PRJNA63737) and motility-deficient (NCBI accession number PRJNA65079) strains found 10 single nucleotide polymorphisms and 5 indels between the genomes. Among these, only the insertional mutation in fcpA (L. interrogans strain Fiocruz L1-130 genome position 3876852) was predicted to disrupt a gene product, indicating that a single spontaneous mutation abolished FcpA protein expression in the motility-deficient strain.

Figure 4. Inactivation of the fcpA gene in Leptospira interrogans.

The figure is a schematic representation of the fcpA loci in the WT Fiocruz L1-130 strain and Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA- strain. The expanded circle shows the site of the frameshift mutation, which occurred in the fcpA gene of the motility-deficient Fiocruz LV2756 strain.

Allelic exchange and genomic complementation confirm that FcpA is a flagellar protein

To confirm that inactivation of the fcpA gene specifically causes loss of translational motility, we used a homologous recombination approach (Fig. 4) to generate a fcpA- mutant of L. interrogans strain Fiocruz L1-130 (Video S3). The resultant mutant, Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA-, not only lacked the expression of FcpA (Fig. 3 line 4) when compared with the wild-type (Fig. 3 line 5), but also exhibited identical phenotypes as observed previously for the motility-deficient strain (Figs. 1 and 3), including loss of translational motility (Video S4).

Complementation of WT fcpA gene into the motility-deficient and fcpA- strains restored the hook-end morphology of cells (Figs. 1B and C), the expression of FcpA (Fig. 3 lines 3 and 6) and translational motility (Videos S5 and S6). PF purified from complemented strains were coiled (Fig. 1D). SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting analysis demonstrated that complementation of the fcpA gene rescued FcpA and other related flagellar proteins expression and confirmed the presence of this protein in the flagella structure (Fig. 3). Altogether, these findings indicate that the lack of FcpA expression resulted in the disappearance of the hook-shaped end of the cell and loss of the coiled morphology of the flagella when purified, ultimately resulting in cells without the ability to produce translational motility.

Generation of fcpA- mutants and complemented strains provided the opportunity to confirm the role of motility in leptospiral pathogenesis. Loss of FcpA in the knock-out strain was also associated with an attenuated phenotype (Table 1) and a statistically significant log increase in the LD50 (Table S1). Complementation restored the virulence phenotype (Table 1) and LD50 to values observed for WT strains (Table S1), showing that motility of leptospires is an essential determinant for virulence and that FcpA plays a key role in this process. Furthermore, complementation of the fcpA gene restored the ability to translocate across cell monolayers (Fig. S1). Knockout and complementation studies thus demonstrate that motility is essential for pathogen penetration and entry into the host, and the leptospires' ability to traverse tissue barriers.

FcpA is essential for the formation of the Leptospira flagellar sheath

Diameters of PF from strains with mutations in fcpA were significantly smaller than WT strains (L1-130 fcpA-, mean 17.6 ± 2.3nm; L1-130 WT, mean 22.8 ± 3.8nm; p <0.0001). Reintroducing the wild-type fcpA restored diameters of PF in complemented strains (LV2756 fcpA-/+, mean 22.1 ± 1.7 nm; Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA-/+, mean 22.1 ± 2.1nm), similar to that of the motile strains, demonstrating that expression of FcpA protein is required to generate PF with appropriate thickness, in addition to maintaining its coiled structure.

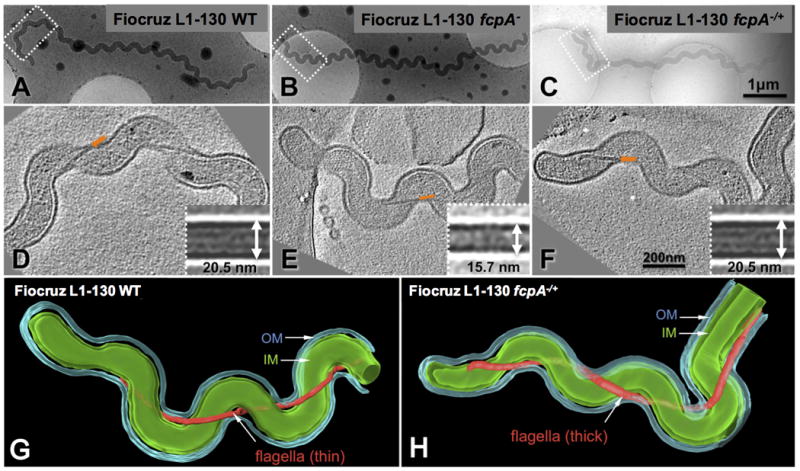

Cryo-electron tomography of intact leptospires confirmed that in situ diameters of PF for WT, fcpA- mutant and complemented strains were similar to those obtained for purified PF preparations. PF of fcpA- (Fig. 5E) were uniformly thinner than PF from WT and complemented strains (Figs. 5D and 5F). In situ three-dimensional reconstructions of intact organisms were generated for fcpA- mutant (Video S7) and complemented strains (Video S8) confirming this finding (Fig. 5). There were no differences found in the fcpA- mutant when compared to the WT or complemented strains with respect to cell morphology or the helical pitch of the flagella along the cell axis.

Figure 5. Cell morphology and structural characterization of periplasmic flagella (PF) in situ for wt, fcpA- mutant and complemented Leptospira interrogans strains.

Cryo-electron tomography was performed for Fiocruz L1-130 WT (A), Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA- (B) and Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA-/+ (C) strains. Panels D, E and F show one slice of a tomographic reconstruction for the regions (boxes in panels A, B and C) of WT Fiocruz L1-130, Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA- and Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA-/+ strains, respectively. Arrows indicate the location of PF. Inserts in panel D, E and F depict averaged maps of PF segments for each of the strains. The diameter of the flagellar filament in Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA- mutant was 15.7 nm, whereas the diameter of filaments in the WT and complemented strains was 20.5 nm. Surface renderings of the corresponding 3-D reconstructions of Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA- (G) and Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA-/+ (H) strains are shown, with prominent structural features including the outer membrane (OM), cytoplasmic membrane (IM) and flagellar filament. See also Videos S7 and S8.

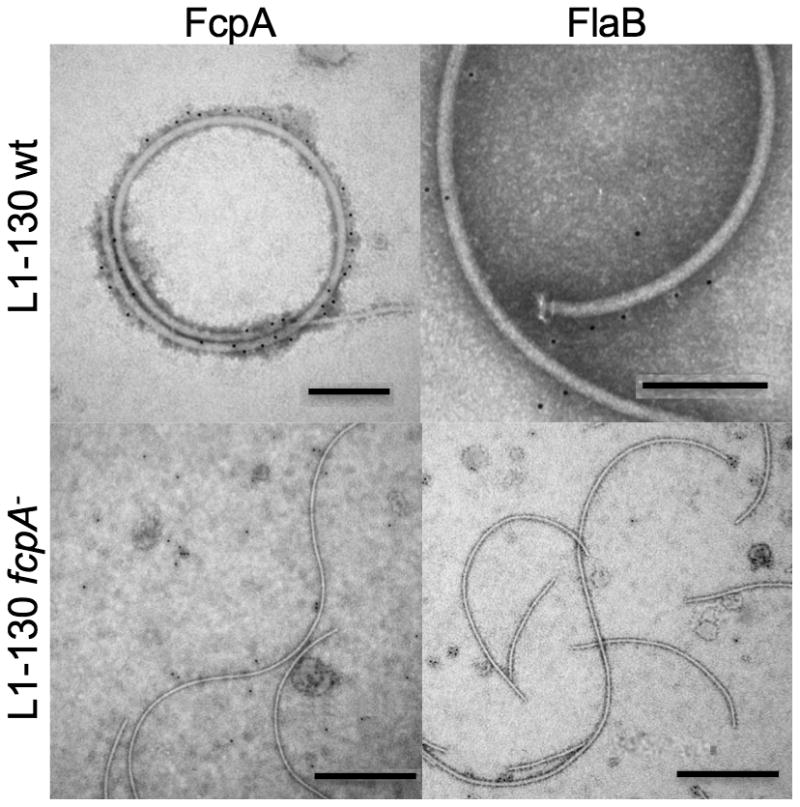

Immuno-electron microscopy demonstrated that anti-FcpA antibodies specifically labeled the surface of PF from WT strains and did not bind to PF from fcpA- strains (Fig. 6). Furthermore, labeling was evenly distributed along the length of wild-type PF. Although antibodies to FlaB1 strongly bound to the respective moiety in immunoblotting assays (Fig. 3B), this antibody did not label PF from WT and fcpA- strains, confirming that FlaB1 is not expressed on the PF surface. These findings, together with the reduced PF diameter observed in fcpA mutants, indicate that FcpA protein is a major component of the leptospiral flagellar sheath.

Figure 6. Immuno-electron microscopy of periplasmic flagella (PF) from wt and fcpA- mutant of Leptospira interrogans strains.

PF from wt Fiocruz L1-130 [bar=200nm] and Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA- [bar=500nm] strains were purified and labeled with antibodies against FcpA (α-FcpA) and FlaB1 (α-FlaB1). Anti-rabbit IgG anti-sera conjugated with 5nm gold nanoparticles were used to detect bound antibodies. PF were visualized using 2% PTA negative staining.

Discussion

Our study provides strong evidence that the leptospiral PF structure determines the cell shape, specifically the hooked end morphology, and in turn, the spirochete's ability to generate translational motility and ultimately virulence. Furthermore, we found that a novel protein, FcpA, is a key component of the PF sheath, and that FcpA is the molecule mediating these phenotypes. In the 1960s, studies of motility-deficient leptospires described the loss of the hooked-end cell morphology and its correlation with small colony phenotype (Simpson & White, 1964) and virulence attenuation (Faine & Vanderhoeden, 1964). However no association between cell morphology and virulence was reported at that time. Bromley et al. characterized a motility-deficient mutant obtained by chemical mutagenesis, which had straight cell ends and yielded uncoiled PF after purification. The authors proposed that the PF contributed to the hooked end cell morphology (Bromley & Charon, 1979), but could not rule out the possibility of secondary mutations. More recently, studies showed that loss of fliY or flaA2 in L. interrogans was associated with attenuated motility and virulence yet, complementation of the gene and rescue of these phenotypes were not performed (Lambert et al., 2012, Liao et al., 2009) . In this study, the construction of fcpA knockout and complemented mutants provided the opportunity to apply Koch's molecular postulates, thus demonstrating that a novel flagellar structural protein, FcpA, is essential for PF structure, cell morphology and translational motility. Inactivation of fcpA resulted in a more than seven-fold increase (≤10 to ≥108) in the LD50 of L. interrogans in the hamster model of leptospirosis, while complementation of fcpA restored the LD50 to that observed for the WT strain. Further indicating that that motility is a key virulence determinant among spirochetal pathogens.

We also found that fcpA- mutant strains were unable to induce infection, as ascertained by PCR detection, when applied to mucous membranes of the conjunctiva, which mimics a natural mode of transmission (Bolin & Alt, 2001, Evangelista & Coburn, 2010). fcpA- mutants were unable to translocate in vitro across polarized mammalian cell monolayers, in contrast to WT and complemented strains (Fig. S1). These finding support the assertion that motility is required for the key initial infection event of host penetration.

FcpA is essential for the formation of the hook-shaped ends of leptospires, but more importantly it appears to interfere in the generation of the spiral waveform during translational motility. Prior studies showed that counterclockwise rotation of PF at the terminal end, as viewed from the center of the cell, creates a backward motion of the spiral wave, which in turn, causes the cylinder to roll clockwise across the body axis (Goldstein & Charon, 1988, Kan & Wolgemuth, 2007, Goldstein & Charon, 1990, Berg et al., 1978). Therefore, in a low viscosity medium leptospires achieve translational motility through counter-clockwise rotation of the PF, gyration of the leading, spiral-shaped end, and generation of a left-handed waveform that travels opposite to the swimming direction. In viscous gel-like media, such as connective tissue, the clockwise roll of the cell cylinder allows the organisms to swim with no slippage (Li et al., 2000b, Berg et al., 1978, Charon et al., 1991, Kan & Wolgemuth, 2007, Goldstein & Charon, 1990). A recent study concluded that the change in the hook-shaped end rotation rate occurs in response to the change in the spiral-shaped end rotation rate, indicating that the hook-shaped end of the cells does not contribute to the translation motion of the cell (Nakamura et al., 2014). Therefore, the phenotype observed in our mutants reflects a disturbance on the gyration of the spiral-shaped end of the cell with concomitant inhibition of rolling of the cell cylinder.

Genetic manipulation of flagellar genes of the spirochete B. hyodysenteriae demonstrated that stiffer PF deform the cell cylinder and that larger deformations produce more thrust (Li et al., 2008). Although fcpA- mutants were able to generate spiral-shaped ends (Videos S2 and S5), gyration of the spiral-shaped ends is either too slow or not large enough to yield sufficient thrust for the bacteria to translate, similar to what is proposed to T. phagedenis in low-viscosity media (Charon et al., 1991). Thus, the perturbed interactions between the PF and cell cylinder due to loss of FcpA, result in qualitatively different effects depending on the direction of rotation. Although speculative, rotation-dependent conformational changes in the PF, due to interactions influenced by FcpA protein within the flagellar assembly, may explain the differences in the spiral and hook-end morphologies observed during translational motility in Leptospira.

We found that FcpA, which was previously found as an abundant protein (Malmstrom et al., 2009), is a major component of the Leptospira flagellar sheath and may play a key role in the interaction between PF and cell cylinder. The loss of FcpA generated a flagellar structure that lost its super-coiled form when purified. We demonstrated that PF from fcpA- mutants were significantly thinner than those from the WT and complemented strains (Fig. 5). The observation of a smaller PF diameter was consistent with a peripheral location of FcpA, which we confirmed in immuno-EM analyses to be surface exposed (Fig. 6). B. hyodysenteriae with a mutation in the flaA gene showed similar results, with the mutant having significant thinner flagella (19.6nm) when compared to the WT strain (25nm) (Li et al., 2000a). Furthermore, the measured diameter for the WT strain (22.8nm) was consistent with previous results for Leptospira spp. (18-25nm) (Nauman et al., 1969). Taking together these results corroborate previous observations of thicker PF in spirochetes compared to E. coli and Salmonella spp. (20nm) (Macnab, 1996). Finally, FcpA appears to play a similar role for PF structure, cell morphology and motility across Leptospira spp. since the same phenotypes were observed in a fcpA- mutant generated in the saprophyte L. biflexa (data not shown).

The function of flagellar sheath likely appears to be highly heterogeneous in spirochetes given the variation in sheath composition. B. hyodysenteriae FlaA influences the shape, stiffness and helicity of PF (Li et al., 2000a, Li et al., 2008). In contrast, preliminary evidence indicates that B. burgdorferi FlaA is located on the surface of the PF proximal to the basal body (Ge et al., 1998, Sal et al., 2008). A recent study found that the two FlaA proteins are not involved in the formation of the flagellar sheath in Leptospira (Lambert et al., 2012). Similarly, our immuno-EM studies did not detect expression of FlaB1 protein on the surface of PF purified from WT or fcpA- mutant strains (Fig. 6). Mutants deficient in FlaA proteins produced PF containing the same pattern of expression of FcpA (data not shown), but lacked hook-shaped ends and translational motility and yielded straight PF when purified (Lambert et al., 2012). Our results showed that the lack of FcpA expression influence the expression of FlaA proteins, thus indicating that FlaA proteins and FcpA contribute to the coiled characteristics of the PF. Exposure of proteins, other than the flagellin ortholog FlaB, on the surface of PF filaments may serve as the structural basis for a sheath, which would adopt the topology of a continuous envelope covering a FlaB core, constituted by four different FlaB isoforms (Malmstrom et al., 2009). This model could be thought of as concentric layers, each one composed homogenously of a distinct set of protein species. The findings we are now reporting suggest that the formation of coiled flagella and hook-shaped ends, and their involvement in translational motility, require a complex set of proteins and interactions. Nevertheless, as in other spirochetes (Li et al., 2008), the distribution of these proteins within the core and sheath of Leptospira PF has not been delineated. Further studies are required to fully elucidate the 3D architecture of the PF filaments from Leptospira, unraveling the exact composition, stoichiometry and network of interactions.

Rotation of the PF leads to changes in the cell shape caused by resistive forces between PF and cell body, which in turn drive the movement of spirochetes (Yang et al., 2011). For that reason, perturbation in the flagellar structure itself and/or the interaction of the flagella with the cell body will generate impaired motility. Our findings generate the hypothesis that partial or total loss of the flagellar sheath lead to a reduced tensile strength of PF and hence inability of fcpA- mutants to generate sufficient thrust. However, mathematical modeling of B. burgdorferi motility proposed the existence of a fluid layer separating the PF and peptidoglycan layer (PG) and that thrust occurs as a result of the resistance created by fluid drag, rather than friction (Yang et al., 2011). Considering that the flagella sheath constitutes the expected interface by which the PF interacts with PG, it is conceivable, as a second mechanistic hypothesis, that the loss of the sheath, whether partial or total, may lead to an impaired adherence of those two structures, which in turn prevents them from engaging properly and thus compromising cell end gyration. It is unclear if the phenotype observed in our mutants is due to either one or both of these posited mechanisms.

Given their unique morphology and structure, spirochetal motility is unusual and by far one of the most complex motility systems among bacteria. In this study, we identified a novel Leptospira protein that is an abundant component of the flagellar sheath and is required for maintenance of the PF structure, as well as its function in determining cell morphology and translational motility. The lack of such an important structural protein clearly affects proper flagellar assembly, and impacts also on the expression of other protein species that constitute such a complex supramolecular assembly. The work presented here is just a starting point, as we are currently pursuing continued efforts to better understand the exact composition and interactions within the flagellar assembly of Leptospira. These data, while completing the puzzle, shall deliver invaluable information about the precise way by which the flagellar structure influences the spirochete's biology. In turn a full structural description may yield new paradigms of flagella-associated motility systems in bacteria.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial strains and whole-genome sequencing

The original clinical isolate and wild-type, knockout and complemented strains were grown in liquid Ellinghausen-McCullough-Johnson-Harris (EMJH) medium (Johnson & Harris, 1967) at 29°C, and observed under dark-field microscopy. Strains were plated onto 1% agar supplemented with EMJH medium and incubated at 29°C for a period of 4 weeks to obtain colonies. E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. When necessary, spectinomycin and/or kanamycin were added to culture media at a concentration of 50 μg/mL. For all virulence studies, the correct number of Leptospira was determined by counting the cells in triplicate using the Petroff-Hausser counting chamber (Fisher Scientific). We performed dark-field microscopy of leptospiral strains with a Zeiss AxioImager.M2 microscope outfitted with an AxioCam MRm camera and analyzed images using the AxioVision 4.8.2 software (Carl Zeiss Microscopy LLC). Genomic DNA was extracted from a pellet of 5mL cultures using the Maxwell®16 (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI). Solexa sequencing was performed to obtain the genome sequence for motile and non-motile strains. SNPs and indels between genomes were identified using SAMtools (http://samtools.sourceforge.net/) and CLC (http://www.clcbio.com/), respectively, after assembly of reads using Stampy software (Lunter & Goodson, 2011). Genome analysis was performed on the 569 genomes of the genus Leptospira which have been sequenced to date (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/?term=leptospira).

Construction of mutant and complemented strains

We obtained knockout fcpA- mutants and complemented strains by allelic exchange (Croda et al., 2008) and Himar1 transposon mutagenesis (Murray et al., 2009), respectively, according to approaches previously described. We used conjugation to transfect plasmid constructs into leptospiral strains (Picardeau, 2008) and selected transformant colonies after plating strains on 1% agar plates of EMJH containing the appropriate antibiotic selection agent. For allelic exchange of the fcpA gene, upstream and downstream regions of the gene were amplified from the genomic DNA of L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain Fiocruz L1-130 using primers FcpA_FlkAF and FcpA_FlkAR for the upstream region and FcpA_FlkBF and FcpA_FlkBR for the downstream region. The PCR products of upstream and downstream region were digested with BamHI and XbaI, and HindIII and SpeI, respectively. The Spectinomycin resistance (SpcR) cassette was amplified using primers Spc_Xba5 and Spc_Hind3, and the PCR product was digested with XbaI and HindIII. The three digested PCR products were transformed into the non-replicative plasmid pSW29T (Picardeau, 2008), previously digested with BamHI and SpeI. The final plasmid, containing the flanking regions of the fcpA gene and SpcR cassette insertion, was transfected into the donor strain E. coli β2163 cells, and introduced into the Fiocruz L1-130 strain by conjugation, as previously described (Picardeau, 2008). After 4 to 6 weeks of plate incubation at 30°C, spectinomycin-resistant transformants were inoculated into liquid EMJH supplemented with 50 μg/mL of spectinomycin, and examined for allelic exchange in the target gene by PCR, using primers FcpA_AscF and FcpA_AscR, and by Western blotting.

For complementation, the fcpA gene with its native promoter region (a 400bp-region upstream the start codon as identified by the Softberry software; http://linux1.softberry.com/berry.phtml?topic=bprom&group=programs&subgroup=gfindb), was amplified with primers FcpA_AscF and FcpA_AscR from L. interrogans strain Fiocruz L1-130. The amplified product, after digestion with AscI, was cloned into the suicide pSW29T_TKS2 plasmid (Picardeau, 2008), which carried a kanamycin-resistant Himar1 transposon. Random insertion mutagenesis by conjugation was carried out in L. interrogans strain Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA- and strain LV 2756 motility deficient, as previously described (Murray et al., 2009). For further characterization of the transposon insertion sites in transformants, semi-random PCR was performed in a set of kanamycin-resistant clones obtained in Fiocruz LV2556 and L1-130 fcpA- as previously described (Murray et al., 2009). For complementation, we selected clones that had the transposon inserted in non-coding regions for further analysis.

In Fiocruz LV2556 fcpA-/+, the transposon was inserted between genes LIC12898 and LIC12899, which encode for a hypothetical and a cytoplasmic membrane protein, respectively. In Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA-/+, the transposon was inserted between genes LIC11818 and LIC11819, both encoding for hypothetical proteins.

Flagella purification and protein analysis

PF were purified using a protocol modified from that described by Trueba et al. (Trueba et al., 1992) and subsequently analysed by SDS-PAGE, MS and electron microscopy. Briefly, 300mL of a broth culture of late-logarithmic-phase cells (approximately 5 × 108 cells/mL) were harvested and centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The cell pellet was re-suspended and washed in 28mL of PBS. The cell pellet was then re-suspended in 30mL of sucrose solution (0.5 M sucrose, 0.15 M Tris, pH 8.0), and centrifuged at 8,000-x g for 15 minutes. Pellet was re-suspended in 8mL of sucrose solution, and stirred on ice for 10 minutes. To remove the spirochete outer membrane sheath, 0.8 mL of a 10% Triton X-100 solution (1% final concentration) was added, the mixture was stirred for 30 minutes at room temperature, and 80μL solution of Lysozyme (10mg/mL) was added slowly and stirred on ice for 5 minutes. Before a 2h stirring at room temperature, 0.8mL of EDTA solution (20mM, pH 8.0) was added slowly. Afterwards, 160μL of MgSO4 solution (0.1M), and 160μL of EDTA solution (0.1M, pH 8.0) were added, both with intervals of 5 minutes with stirring at room temperature. The suspension was centrifuged at 17,000 × g for 15 minutes, and the supernatant fluid was mixed well with 2mL of PEG 8000 solution (20%) in 1M NaCl), and kept on ice for 30 minutes. After centrifugation at 27,000 × g for 30 minutes, the pellet was re-suspended in 3mL of H2O, and a new centrifugation was performed, at 80,000 × g for 45 minutes. The final pellet, consisting of purified PF, was suspended in 1mL of H2O and stored at 4C. SDS/PAGE and Western blotting of leptospiral cell lysates and purified PF were carried out as previously described (Croda et al., 2008, Lourdault et al., 2011). Western blot analyses were performed with polyclonal antibodies prepared against recombinant proteins of leptospiral flagellar components. Quantitative analysis of protein expression was done using Image Lab&trade Software (Bio-Rad). Mass spectrometry analysis (MS + MS/MS) of the whole cell lysates and PF preparations of the L. interrogans strain LV 2756 motile and strain LV 2756 motility-deficient were carried out by analyzing fragments of the polyacrylamide gel stained with coomassie blue, according to protocols of the Proteomics Platform of the Institute Pasteur, Paris, France (http://www.pasteur.fr/ip/easysite/pasteur/fr/recherche/plates-formes-technologiques/proteopole/modules/pf3-proteomique). Two independent experiments for each sample and strain were performed.

Transmission electron microscopy

Late log-phase cultures (5mL) were centrifuged at 3.000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed and 5 mL of fixative containing 2% glutaraldehyde and sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) 0,1M was added to the pelleted cells. The cells were fixed for 1h at 4°C and then placed on coverslips treated with poly-L-lysine. After this step, the cells were post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide and treated with a graded series of ethanol solutions. The samples were subjected to critical point drying and sputter coating with gold and then examined using a JEOL 6390LV scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

Purified PF (10μL) were allowed to adsorb for 60s onto a copper grid coated with Formvar 400 mesh. The grid was washed three times with 0.1M Sodium Cacodylate and then negatively stained with 2% (w/v) phosphotungstic acid (PTA) pH 7.2. Grids were observed using a JEOL JEM1230 transmission electron microscope (TEM) operating at 80keV. For the diameter and length measurement of the flagella, twenty random pictures were taken from each group on the same magnification (200.000 x), using Gatan camera and software DigitalMicrograph® for acquisition. For PF thickness, four different measurements were taken from each strain, using the ImageJm1.45s software. For PF length, measurement was taken from 20 different flagella of each strain using Illustrator CS 5.5 (Adobe). Mean values and standard deviations of measurements were used for comparison between groups.

Immuno-electron microscopy

Purified PF (15μL) were allowed to adsorb for 10min in glow-discharged copper grids coated with Formvar 300 mesh. Immediately the grids were blocked for 2min in 0.1% BSA, and incubated for 20min with 1:10 dilution (0.1% BSA) of primary antibody. Polyclonal antibodies anti-FlaA1, FlaA2, anti-FlaB1, and FcpA were used as primary antibodies. Grids were washed 3 times with ultrapure water, and blocked again in 0.1% BSA for 2min. Secondary antibody 5nm gold-conjugated Protein A (PAG) was used in a dilution of 1:50 (0.1% BSA), incubated for 20min. Grids were washed three times with ultrapure water and then negatively stained with 2% PTA pH 7. Grids were observed using a Philips TECNAI 12 BioTwin II operating at 80keV. Images were acquired on Soft Imaging System Morada camera using iTEM image acquisition software.

Dark-field video microscopy

Log phase cultures (100μL) was diluted into 900μL of 1% methyl cellulose (MP Biomedicals) in 0.1μm-filtered ultrapure water (Sigma) and mixed by inverting gently. 10μL of the 1:10 dilution was transferred to a glass microscope slide (Thermo Scientific), an 18x18mm glass coverslip (Carl Zeiss) was applied, and the edges of the coverslip were sealed with clear nail polish (LA Colors) to prevent drying. The slides were immediately viewed in an Axio Imager.M2 motorized dark-field microscope (Carl Zeiss). Videos for qualitative analysis were recorded at 100X (EC Plan-Neofluar 100x/1.30 Oil) under oil immersion (Zeiss Immersol 518F) on an AxioImagerM3 camera (Carl Zeiss) and analyzed using AxioVision 4.8.2 software (Carl Zeiss).

Video tracking analysis

Digital high-speed videos for tracking were recorded at 200ms intervals for up to 10 seconds (50 frames at 5 fps; digital gain = 1; sensitivity = 100%; image orientation = flipped vertically) and all videos recorded were analyzed using the AxioVision Tracking Module (Carl Zeiss). Inclusion criteria for tracking consisted of all leptospires whose search area was entirely within the field of view at the start frame and in the plane of focus at the start frame. Aggregates or chains of two or more leptospires were excluded from tracking, as were leptospires whose tracks could not be followed by the computer algorithm. The instantaneous velocity of each tracked leptospire was recorded by the tracking software at each frame by comparison to the preceding frame, and the mean velocity for each leptospire was calculated by averaging the instantaneous velocities of that particular leptospire and reported by the software as a mean velocity for each of the individual leptospires tracked in a given video.

Cryo-electron tomography and 3D reconstruction

Viable bacterial cultures were centrifuged to increase the concentration to ∼2x109 cells/ml. Five-microliter samples were deposited onto freshly glow-discharged holey carbon grids for 1 min. The grids were blotted with filter paper and rapidly frozen in liquid ethane using a gravity-driven plunger apparatus as previously described (Raddi et al., 2012). The resulting frozen-hydrated specimens were imaged at -170°C using a Polara G2 electron microscope (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR) equipped with a field emission gun and a 4K × 4K charge-coupled-device (CCD) (16-megapixel) camera (TVIPS; GMBH, Germany). The microscope was operated at 300 kV with a magnification of x 31,000, resulting in an effective pixel size of 5.6 Å after 2 × 2 binning. Using the FEI “batch tomography” program, low-dose single-axis tilt series were collected from each bacterium at -6 μm defocus with a cumulative dose of ∼100 e-/Å2 distributed over 87 images, covering an angular range from -64° to +64°, with an angular increment of 1.5°. Tilted images were aligned and then reconstructed using IMOD software package (Kremer et al., 1996). In total, 10, 15 and 17 reconstructions were generated from WT, fcpA mutant and complemented strains, respectively.

A total of 1392 segments (192 × 192 × 96 voxels) of flagellar filaments were manually identified and extracted from 42 reconstructions. The initial orientation was determined using two adjacent points along the filament. Further rotational alignment is performed to maximize the cross-correlation coefficient. Averaging is carried out with a merging procedure in reciprocal space (Raddi et al., 2012). Tomographic reconstructions were visualized using IMOD (Kremer et al., 1996). Reconstruction of cells were segmented using 3D modeling software Amira (Visage Imaging). 3D segmentations of the cytoplasmic, outer membranes and flagellar filaments were manually constructed.

In vitro translocation assays with polarized MDCK cell monolayers

We performed a translocation assay according to a protocol modified from that described by Figueira et al. (Figueira et al., 2011). MDCK cells at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells in 500 μl of DMEM were seeded onto 12-mm-diameter Transwell filter units with 3- μm pores (COSTAR). Monolayers were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 3 to 4 days with daily changes in media until the transepithelial resistance (TER) reached a range of 200 and 300Ω/cm2, as measured with an epithelial voltohmmeter (EVOM, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, Fla.). The TER for polycarbonate filters without cells was approximately 100Ω/cm2. The upper chamber of the transwell apparatus was inoculated with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 leptospires by adding 500μL of bacteria, which were resuspended in 1:2 v/v ratio of DMEM and EMJH media. Duplicate transwell chamber assays were performed for each leptospiral strain tested. Aliquots were removed from lower chamber (100μl) at 2, 4, 6 and 24 hours and the number of leptospires were counted in triplicate by using the Petroff-Hausser counting chamber (Fisher Scientific). The ability of leptospires to translocate MDCK polarized monolayers was determined by calculating the proportion of leptospires in the lower chamber in comparison to the initial inoculums for duplicate assays at each time point.

Virulence studies

Animal experiments were conducted according to National Institutes of Health guidelines for housing and care of laboratory animals and protocols, which were approved by the Yale University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol # 2014-11424). All the experiments were performed using 3-6 week-old Golden Syrian male hamsters. For the experiments of virulence, one group of 8-10 animals for each of the six strains was inoculated intraperitoneally (IP) with a high-dose inoculum (108 leptospires) in 1ml of EMJH medium. For the LD50 experiments (Reed & Muench, 1938), two groups of 4 animals were inoculated IP with doses of 103, 102 and 10 leptospires, for motile LV2756, LV2756 fcpA-/+, Fiocruz L1-130 WT and Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA-/+. For motility-deficient LV2756 and Fiocruz L1-130 fcpA- strains, animals were infected with doses of 108 and 107 leptospires. In all experiments, animals were monitored twice daily for clinical signs of leptospirosis and death, up to 21 days post-infection. Moribund animals presenting difficulties to move, breath or signs of bleeding or seizure were immediately sacrificed by inhalation of CO2.

In experiments evaluating leptospiral dissemination, one group of six animals for strains LV2756 motile and LV2756 motility deficient was inoculated intraperitoneally with 108 leptospires in 1ml of EMJH medium. After 1 hour and 4 days post-infection, sub-groups of two animals were euthanized. With the same strains, a conjunctival infection was performed by centrifugation of 30ml culture of leptospires for 10 minutes at 1000rcf and using an inoculum of 108 leptospires in 10μl of EMJH medium instilled in the left eye conjunctiva using a micropipette. Groups of four animals were infected and two were euthanized after 7 days of infection for each strain tested. In those experiments, a group of two animals were left as positive controls.

The necropsy for the dissemination study was performed as follows. Animals were sacrificed by inhalation of CO2 and placed on their backs slightly inclined in the dissecting tray. After sterilization of the abdomen with alcohol 70% and using sets of sterile instruments, the internal organs were exposed, including the heart and lungs. All blood was collected directly from the heart in a Vacutainer® K2 EDTA Tubes (BD Diagnostics) and Glass Serum Tubes, using a 5ml syringe with a 21G needle. A 21G butterfly needle affixed to a 60ml syringe containing sterile saline 0.85% was then inserted into the left ventricle. The right atrium was snipped to allow the residual blood and normal saline to leave the body during the perfusion. Each hamster was perfused with 100ml of saline solution. After perfusion, right pulmonary lobe, right dorsocaudal hepatic lobe, spleen, right kidney and right eye were carefully removed. All the tissues were collected into cryotubes and immediately placed into liquid nitrogen before being stored at -80°C until extraction. Blood, kidney, liver, lung, spleen and eye were analyzed. Using scissors and scalpels, 25mg of lung, liver, kidney cortex, and eye, 10mg of the spleen, and 200μl of blood were aseptically collected. DNA was extracted using the Maxwell®16 Tissue DNA purification Kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI), after homogenization with Bullet Blender (Next Advance, Averill Park, NY).

Quantitative real-time PCR evaluation of bacterial load

Quantitative Real-time PCR assays were performed using an ABI 7500 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and Platinum Quantitative PCR SuperMix-UDG (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). The lipL32 gene was amplified using the set of primers and probe (Table S1), according to protocol previously described (Stoddard et al., 2009). We performed amplifications of hamster housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phophate dehydrogenase (gapdh) as a control to monitor nucleic acid extraction efficiency and to evaluate for potential inhibition of the amplification reaction. GAPDH_F and GAPDH_R primers were designed to amplify a fragment that was detected by the probe, GAPDH_P. A sample with a threshold cycle (Ct) value between 16 and 21 was considered as positive and further analyzed by real-time PCR targeting lipL32. In case of sample for which the gapdh gene sequence did not amplify, a new DNA extraction of the sample was performed and analyzed by PCR. For each organ, the DNA was extracted from one sample and the Real Time PCR was performed in duplicate, including a standard curve of genomic DNA from L. interrogans serovar Fiocruz L1-130 (100–107 leptospires) and 12 negative control wells (water) per plate. Considering the amount of tissue that was used for DNA extraction, an equation was applied to express the results as the number of leptospires per gram of tissue or per mL of blood/water.

Statistical analysis

Fisher's exact test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were performed to assess statistical significance of differences between pairs of groups and multiple groups, respectively. A p value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Gisele R. Santos and Drs. Leyla Slamti, Kristel Lourdault and Vimla Bisht for their technical assistance. We also thank Dr. David Haake for providing polyclonal antibodies (α-FlaA1) and for his helpful discussions, Drs. Joe Vinetz and Derrick Fouts for their collaboration in sequencing the genomes of leptospiral strains, and Dr. Justin Radolf for his suggestions and advice throughout the study. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (U01 AI0038752, R01 AI052473, R01 TW009504, D43 TW000919, R01 DE0234431, R01 AI29743 and R01 AI087946), Brazilian National Research Council (CNPq), French Ministry of Research (ANR-08-MIE-018) and the Welch Foundation (AU-1714).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Berg HC. The rotary motor of bacterial flagella. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:19–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg HC, Bromley DB, Charon NW. Leptospiral motility. In: Stanier RY, Rogers HJ, Ward JB, editors. Relations between structure and function in the prokaryotic cell: 28th Symposium of the Society for General Microbiology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1978. pp. 285–294. [Google Scholar]

- Bharti AR, Nally JE, Ricaldi JN, Matthias MA, Diaz MM, Lovett MA, Levett PN, Gilman RH, Willig MR, Gotuzzo E, Vinetz JM. Leptospirosis: a zoonotic disease of global importance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:757–771. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00830-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolin CA, Alt DP. Use of a monovalent leptospiral vaccine to prevent renal colonization and urinary shedding in cattle exposed to Leptospira borgpetersenii serovar hardjo. American journal of veterinary research. 2001;62:995–1000. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2001.62.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahamsha B, Greenberg EP. Cloning and sequence analysis of flaA, a gene encoding a Spirochaeta aurantia flagellar filament surface antigen. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1692–1697. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.3.1692-1697.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromley DB, Charon NW. Axial filament involvement in the motility of Leptospira interrogans. J Bacteriol. 1979;137:1406–1412. doi: 10.1128/jb.137.3.1406-1412.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charon NW, Cockburn A, Li C, Liu J, Miller KA, Miller MR, Motaleb MA, Wolgemuth CW. The unique paradigm of spirochete motility and chemotaxis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2012;66:349–370. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charon NW, Goldstein SF. Genetics of motility and chemotaxis of a fascinating group of bacteria: the spirochetes. Annu Rev Genet. 2002;36:47–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.36.041602.134359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charon NW, Goldstein SF, Curci K, Limberger RJ. The bent-end morphology of Treponema phagedenis is associated with short, left-handed, periplasmic flagella. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4820–4826. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.15.4820-4826.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockayne A, Bailey MJ, Penn CW. Analysis of sheath and core structures of the axial filament of Treponema pallidum. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:1397–1407. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-6-1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa F, Hagan JE, Calcagno J, Kane M, Torgerson P, Martinez-Silveira MS, Stein C, Abela-Ridder B, Ko AI. Global Morbidity and Mortality of Leptospirosis: A Systematic Review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003898. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croda J, Figueira CP, Wunder EA, Jr, Santos CS, Reis MG, Ko AI, Picardeau M. Targeted mutagenesis in pathogenic Leptospira species: disruption of the LigB gene does not affect virulence in animal models of leptospirosis. Infect Immun. 2008;76:5826–5833. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00989-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evangelista KV, Coburn J. Leptospira as an emerging pathogen: a review of its biology, pathogenesis and host immune responses. Future Microbiol. 2010;5:1413–1425. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faine S, Vanderhoeden J. Virulence-Linked Colonial and Morphological Variation in Leptospira. J Bacteriol. 1964;88:1493–1496. doi: 10.1128/jb.88.5.1493-1496.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueira CP, Croda J, Choy HA, Haake DA, Reis MG, Ko AI, Picardeau M. Heterologous expression of pathogen-specific genes ligA and ligB in the saprophyte Leptospira biflexa confers enhanced adhesion to cultured cells and fibronectin. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y, Li C, Corum L, Slaughter CA, Charon NW. Structure and expression of the FlaA periplasmic flagellar protein of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2418–2425. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2418-2425.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein SF, Charon NW. Motility of the spirochete Leptospira. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1988;9:101–110. doi: 10.1002/cm.970090202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein SF, Charon NW. Multiple-exposure photographic analysis of a motile spirochete. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4895–4899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.4895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouveia EL, Metcalfe J, de Carvalho AL, Aires TS, Villasboas-Bisneto JC, Queirroz A, Santos AC, Salgado K, Reis MG, Ko AI. Leptospirosis-associated severe pulmonary hemorrhagic syndrome, Salvador, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:505–508. doi: 10.3201/eid1403.071064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs RD, Hanke JH, Guzman-Verduzco LM, Newport G, Agabian N, Norgard MV, Lukehart SA, Radolf JD. Molecular cloning and DNA sequence analysis of the 37-kilodalton endoflagellar sheath protein gene of Treponema pallidum. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3403–3411. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3403-3411.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RC, Harris VG. Differentiation of pathogenic and saprophytic letospires. I. Growth at low temperatures. J Bacteriol. 1967;94:27–31. doi: 10.1128/jb.94.1.27-31.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan W, Wolgemuth CW. The shape and dynamics of the Leptospiraceae. Biophys J. 2007;93:54–61. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.103143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko AI, Galvao M, Reis CM, Ribeiro Dourado, Johnson WD, Jr, Riley LW. Urban epidemic of severe leptospirosis in Brazil. Salvador Leptospirosis Study Group. Lancet. 1999;354:820–825. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)80012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko AI, Goarant C, Picardeau M. Leptospira: the dawn of the molecular genetics era for an emerging zoonotic pathogen. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:736–747. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J Struct Biol. 1996;116:71–76. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert A, Picardeau M, Haake DA, Sermswan RW, Srikram A, Adler B, Murray GA. FlaA proteins in Leptospira interrogans are essential for motility and virulence but are not required for formation of the flagellum sheath. Infect Immun. 2012;80:2019–2025. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00131-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Corum L, Morgan D, Rosey EL, Stanton TB, Charon NW. The spirochete FlaA periplasmic flagellar sheath protein impacts flagellar helicity. J Bacteriol. 2000a;182:6698–6706. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.23.6698-6706.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Motaleb A, Sal M, Goldstein SF, Charon NW. Spirochete periplasmic flagella and motility. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000b;2:345–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Wolgemuth CW, Marko M, Morgan DG, Charon NW. Genetic analysis of spirochete flagellin proteins and their involvement in motility, filament assembly, and flagellar morphology. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:5607–5615. doi: 10.1128/JB.00319-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao S, Sun A, Ojcius DM, Wu S, Zhao J, Yan J. Inactivation of the fliY gene encoding a flagellar motor switch protein attenuates mobility and virulence of Leptospira interrogans strain Lai. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:253. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limberger RJ. The periplasmic flagellum of spirochetes. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;7:30–40. doi: 10.1159/000077867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Howell JK, Bradley SD, Zheng Y, Zhou ZH, Norris SJ. Cellular architecture of Treponema pallidum: novel flagellum, periplasmic cone, and cell envelope as revealed by cryo electron tomography. J Mol Biol. 2010;403:546–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lourdault K, Cerqueira GM, Wunder EA, Jr, Picardeau M. Inactivation of clpB in the Pathogen Leptospira interrogans Reduces Virulence and Resistance to Stress Conditions. Infect Immun. 2011;79:3711–3717. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05168-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunter G, Goodson M. Stampy: a statistical algorithm for sensitive and fast mapping of Illumina sequence reads. Genome Res. 2011;21:936–939. doi: 10.1101/gr.111120.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macnab RM. Flagella and Motility. In: Neidhardt FC, Curtiss R III, Ingraham JL, Lin ECC, Low KB, Magasanik B, Reznikoff WS, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger HE, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- Malmstrom J, Beck M, Schmidt A, Lange V, Deutsch EW, Aebersold R. Proteome-wide cellular protein concentrations of the human pathogen Leptospira interrogans. Nature. 2009;460:762–765. doi: 10.1038/nature08184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride AJ, Athanazio DA, Reis MG, Ko AI. Leptospirosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2005;18:376–386. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000178824.05715.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motaleb MA, Corum L, Bono JL, Elias AF, Rosa P, Samuels DS, Charon NW. Borrelia burgdorferi periplasmic flagella have both skeletal and motility functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10899–10904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200221797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motaleb MA, Sal MS, Charon NW. The decrease in FlaA observed in a flaB mutant of Borrelia burgdorferi occurs posttranscriptionally. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:3703–3711. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.12.3703-3711.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray GL, Morel V, Cerqueira GM, Croda J, Srikram A, Henry R, Ko AI, Dellagostin OA, Bulach DM, Sermswan RW, Adler B, Picardeau M. Genome-wide transposon mutagenesis in pathogenic Leptospira species. Infect Immun. 2009;77:810–816. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01293-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S, Leshansky A, Magariyama Y, Namba K, Kudo S. Direct measurement of helical cell motion of the spirochete leptospira. Biophys J. 2014;106:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.11.1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento AL, Verjovski-Almeida S, Van Sluys MA, Monteiro-Vitorello CB, Camargo LE, Digiampietri LA, Harstkeerl RA, Ho PL, Marques MV, Oliveira MC, Setubal JC, Haake DA, Martins EA. Genome features of Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2004;37:459–477. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2004000400003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauman RK, Holt SC, Cox CD. Purification, ultrastructure, and composition of axial filaments from Leptospira. J Bacteriol. 1969;98:264–280. doi: 10.1128/jb.98.1.264-280.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi H. Spirochaeta Icterohaemorrhagiae in American Wild Rats and Its Relation to the Japanese and European Strains : First Paper. J Exp Med. 1917;25:755–763. doi: 10.1084/jem.25.5.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picardeau M. Conjugative transfer between Escherichia coli and Leptospira spp. as a new genetic tool. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:319–322. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02172-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picardeau M. Genomics, proteomics, and genetics of leptospira. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2015;387:43–63. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-45059-8_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picardeau M, Brenot A, Saint Girons I. First evidence for gene replacement in Leptospira spp. Inactivation of L. biflexa flaB results in non-motile mutants deficient in endoflagella. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:189–199. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raddi G, Morado DR, Yan J, Haake DA, Yang XF, Liu J. Three-dimensional structures of pathogenic and saprophytic Leptospira species revealed by cryo-electron tomography. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:1299–1306. doi: 10.1128/JB.06474-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed LJ, Muench H. A Simple Method of Estimating Fifty Per Cent Endpoints. American Journal of Hygiene. 1938;27:5. [Google Scholar]

- Sal MS, Li C, Motalab MA, Shibata S, Aizawa S, Charon NW. Borrelia burgdorferi uniquely regulates its motility genes and has an intricate flagellar hook-basal body structure. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:1912–1921. doi: 10.1128/JB.01421-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson CF, White FH. Ultrastructural Variations between Hooked and Nonhooked Leptospires. J Infect Dis. 1964;114:69–74. doi: 10.1093/infdis/114.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stimson AM. Public Health Weekly Reports for May 3, 1907. Public Health Rep. 1907;22:541–581. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard RA, Gee JE, Wilkins PP, McCaustland K, Hoffmaster AR. Detection of pathogenic Leptospira spp. through TaqMan polymerase chain reaction targeting the LipL32 gene. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;64:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trueba GA, Bolin CA, Zuerner RL. Characterization of the periplasmic flagellum proteins of Leptospira interrogans. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4761–4768. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.14.4761-4768.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolgemuth CW, Charon NW, Goldstein SF, Goldstein RE. The flagellar cytoskeleton of the spirochetes. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;11:221–227. doi: 10.1159/000094056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Huber G, Wolgemuth CW. Forces and torques on rotating spirochete flagella. Phys Rev Lett. 2011;107:268101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.268101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.