Abstract

Purpose

Inpatient palliative care consultation (IPCC) may help address barriers that limit the use of hospice and the receipt of symptom-focused care for racial/ethnic minorities, yet little is known about disparities in the rates of IPCC. We evaluated the association between race/ethnicity and rates of IPCC for patients with advanced cancer.

Patients and Methods

Patients with metastatic cancer who were hospitalized between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2010, at an urban academic medical center participated in the study. Patient-level multivariable logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between race/ethnicity and IPCC.

Results

A total of 6,288 patients (69% non-Hispanic white, 19% African American, and 6% Hispanic) were eligible. Of these patients, 16% of whites, 22% of African Americans, and 20% of Hispanics had an IPCC (overall P < .001). Compared with whites, African Americans had a greater likelihood of receiving an IPCC (odds ratio, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.44), even after adjusting for insurance, hospitalizations, marital status, and illness severity. Among patients who received an IPCC, African Americans had a higher median number of days from IPCC to death compared with whites (25 v 17 days; P = .006), and were more likely than Hispanics (59% v 41%; P = .006), but not whites, to be referred to hospice.

Conclusion

Inpatient settings may neutralize some racial/ethnic differences in access to hospice and palliative care services; however, irrespective of race/ethnicity, rates of IPCC remain low and occur close to death. Additional research is needed to identify interventions to improve access to palliative care in the hospital for all patients with advanced cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Racial/ethnic minorities with advanced cancer are less likely to receive hospice services than non-Hispanic whites,1–7 and more likely to receive intensive, noncurative treatment at the end of life.5,6,8–12 Such nonbeneficial end-of-life care has been associated with decreased quality of life and higher costs.13,14 Integration of early palliative care with standard oncology care has been shown to improve quality of life, decrease overly aggressive care at the end of life, and possibly even lengthen survival.15 In addition, use of hospice has been associated with lower rates of hospitalization, fewer admissions to the intensive care unit, fewer invasive procedures at the end of life, and decreased costs.16 Although numerous studies have found decreased hospice enrollment for minorities in community-based samples,1 a recent study by Enguidanos et al17 found that among patients who received an inpatient palliative care consultation (IPCC), rates of hospice enrollment were not significantly different between white and African American patients.

African American patients with cancer are more likely than whites to receive end-of-life care in the hospital.5 IPCC may thus provide an important opportunity to improve access to palliative care and hospice services for racial/ethnic minorities.17 In the hospital, IPCC improves symptom management, facilitates physician-patient communication about prognosis and end-of-life decision making, and provides emotional support to patients and family members.17 IPCC has also been associated with lower health care costs18–20 and decreased use of the intensive care unit at the end of life.18,21

Identification of effective interventions that also help decrease disparities in end-of-life care is critical.22 As noted, IPCC may be one such intervention; however, little is known about racial/ethnic differences in rates of IPCC for patients with advanced cancer. The objective of this study was to evaluate the association between race/ethnicity and IPCC rates for patients hospitalized at a large, urban academic medical center. We hypothesized that the disparities in use of palliative care in the outpatient setting would be attenuated in the hospital, and that rates of IPCC would not differ by race/ethnicity.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design, Patients, and Setting

We conducted a retrospective medical record review of patients with metastatic cancer admitted to Northwestern Memorial Hospital (Chicago, IL) between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2010, using the Northwestern University Enterprise Data Warehouse. We identified patients with metastatic cancer by using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification codes (Appendix Table A1, online only).23,24 The protocol was approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Patient characteristics.

We obtained sociodemographic and clinical characteristics from the medical record. Race/ethnicity data are completed on admission by patients or registration staff on the basis of surname and racial/ethnic phenotype. We identified the patient's primary cancer using clinical classification software (Appendix Table A2, online only).25–27 Illness severity was assessed by the all-patient refined diagnosis-related group (APR-DRG) score, which ranges from 1 to 4, indicating minor to extreme complexity.28 Number of hospitalizations and presence of a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order were obtained from the medical record. Because the distribution of hospitalizations for each patient was highly skewed, we dichotomized multiple hospitalizations as “yes” (greater than one hospitalization during the study period) or “no.” We identified all patients who died at Northwestern from the medical record and searched the Death Master File of the US Social Security Administration to identify the date of death for other patients. By using this method, we captured deaths entered into the file as of March 2014.

Census data.

We used geocoding to obtain neighborhood-level measures of socioeconomic status. Patient addresses were matched to a census block group, comprising approximately 1,000 individuals, which was linked to 2010 US Census data. Census block group data included education, poverty level, and median household income. Education was categorized as less than high school versus high school or above; we then defined a low educational attainment area as a census block group with 20% or greater of adults with less than a high school education.29 Block groups with 20% or greater of families living below the federal poverty level were identified as a high poverty–level area.29

IPCC characteristics.

The primary outcome was receipt of IPCC. IPCC was dichotomized as “yes” (documentation of an IPCC during any of the patient's hospitalizations) or “no.” Patients were considered to have had a hospice referral if their discharge disposition was listed as “hospice” in the medical record or if the word “hospice” was documented in case management notes. As a measure of symptom management, we abstracted data on the presence of a medication order for long-acting opioids during any of the patient's hospitalizations (yes/no). Receipt of an IPCC on the patient's first hospitalization during the study period was dichotomized as yes/no. Median days from the first admission date to the first IPCC date were calculated, as were the median days from first IPCC to death.

Statistical Analysis

We evaluated racial/ethnic differences in patient characteristics for the full sample, and separately for the subset of patients who had an IPCC, using χ2, Wilcoxon rank sum, or independent sample t tests, as appropriate, to compare racial/ethnic groups overall. Pairwise comparisons (eg, African American v white, African American v Hispanic, and Hispanic v white) were considered to be statistically significant if the corresponding unadjusted pairwise P < .017 (ie, < .05/3 for Bonferroni correction). We restricted our analysis to white, African American, and Hispanic patients. Patient-level logistic regression analyses were used to identify associations between race/ethnicity and IPCC. Patient-level variables that were P < .20 in univariable analyses were included in the multivariable logistic regression model.

Kaplan-Meier curves summarized distributions of times to death (number of days since index date) by race/ethnicity, illness severity, and IPCC; these were compared using log-rank tests. The index date (time 0) was the date of the patient's first hospitalization during the study period. Patients with no death date were censored at their last discharge date. Additional Kaplan-Meier curves were generated to evaluate racial/ethnic differences in survival for patients who had an IPCC. A Cox proportional hazards model for time to death was constructed, adjusting for illness severity, to evaluate race/ethnicity as a predictor of survival. Exploratory analyses assessed evidence of an interaction between race/ethnicity and illness severity when developing the final multivariable model. We evaluated racial/ethnic differences in time to IPCC, censoring patients at death or last discharge date. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

A total of 6,288 patients with metastatic cancer were identified. Of these patients, 69% were white (n = 4,312), 19% were African American (n = 1,191), 6% were Hispanic (n = 366), and 7% were other/unknown (n = 419). Table 1 displays sample characteristics by race/ethnicity. Insurance status differed by race/ethnicity (P < .001), with 17.3% of African Americans and 20.2% of Hispanics having Medicaid compared with 3.1% of whites. Marital status differed across racial/ethnic groups, with whites being more likely (61.3%) and African Americans less likely (32.7%) to be married than Hispanics (53.8%). More African American patients than whites were female (65.4% v 55.7%; P < .001). Hispanics were younger than African Americans and whites (P < .001). Severity of illness differed between African American and white patients (P < .001), and African American and Hispanic patients were more likely to have multiple hospitalizations than whites (P < .001 and P = .007, respectively). Less than 25% of patients had a DNR order and less than 10% of patients died in the hospital; these characteristics did not differ by race/ethnicity.

Table 1.

Study Sample Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristic | White (n = 4,312) | AA (n = 1,191) | Hispanic (n = 366) | P (AA v white)* | P (Hispanic v white)* | P (AA v Hispanic)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic and clinical patient characteristics | ||||||

| Age, mean (SD), years | 61.0 (15.3) | 59.9 (14.6) | 53.8 (17.2) | .03 | < .001 | < .001 |

| Female, % | 55.7 | 65.4 | 58.5 | < .001 | .28 | .02 |

| Married, % | 61.3 | 32.7 | 53.8 | < .001 | .005 | < .001 |

| Cancer type, %† | < .001 | .010 | < .001 | |||

| Lymph/heme | 27.5 | 22.0 | 32.0 | |||

| Breast | 13.8 | 17.2 | 12.6 | |||

| Noncolon GI | 7.9 | 8.9 | 11.4 | |||

| Lung | 7.6 | 8.6 | 3.6 | |||

| Colorectal | 6.5 | 9.7 | 7.2 | |||

| Other | 36.7 | 33.6 | 33.2 | |||

| Payor, % | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | |||

| Private insurance | 50.4 | 30.5 | 39.6 | |||

| Medicaid | 3.1 | 17.3 | 20.2 | |||

| Medicare | 44.0 | 46.8 | 33.1 | |||

| Self-pay | 0.4 | 1.4 | 1.1 | |||

| VA | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | |||

| Other/unknown | 2.1 | 4.0 | 6.0 | |||

| APR severity of illness, % | ||||||

| 1 | 20.3 | 16.3 | 16.9 | < .001 | .28 | .09 |

| 2 | 40.3 | 38.1 | 44.8 | |||

| 3 | 29.8 | 35.6 | 29.5 | |||

| 4 | 9.6 | 9.8 | 8.7 | |||

| Multiple hospitalizations, % yes‡ | 47.0 | 54.2 | 54.4 | < .001 | .007 | .97 |

| DNR order, % yes | 21.9 | 23.8 | 19.1 | .17 | .22 | .06 |

| Long-acting opioid, % yes | 89.0 | 89.6 | 90.2 | .57 | .50 | .75 |

| Palliative care consult, % yes | 15.8 | 21.8 | 20.0 | < .001 | .04 | .44 |

| Hospice referral, % yes | 11.0 | 15.9 | 13.1 | < .001 | .23 | .20 |

| In-hospital death, % yes | 9.1 | 10.1 | 8.7 | .31 | .81 | .45 |

| Neighborhood-level socioeconomic status | ||||||

| % Living in low educational area§ | 27.5 | 24.6 | 28.5 | .06 | .70 | .16 |

| % Living in high poverty area‖ | 20.8 | 18.6 | 22.5 | .21 | .53 | .18 |

| Household income, median (IQR), $¶ | 54,259 (39,594-73,804) | 56,217 (40,791-77,660) | 53,102 (39,556-68,403) | .08 | .23 | .03 |

Abbreviations: AA, African American; APR, all-patient refined; DNR, do not resuscitate; IQR, interquartile range; lymph/heme, cancers of lymphatic and hematopoietic tissue; noncolon GI, GI cancers other than colorectal cancer; VA, Veterans Affairs.

P values were calculated using independent sample t tests for continuous variables, χ2 tests for categorical variables, and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for medians. The reported P values are based on pairwise comparisons among groups, and the significance level is based on Bonferroni-adjusted P < .017.

Type of cancer was based on International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, codes and was missing for 402 patients. The most frequent cancer types are presented. Lung cancer includes cancer of the lung and bronchus. See Appendix Table A2 for the breakdown of other types of cancer.

Patient had more than one hospitalization during the study period. If patients had a palliative care consult on their first hospitalization, they were considered to have had a single hospitalization.

Low educational attainment area is defined as a census block group with 20% or greater of adults with less than a high school education (n = 5,119 because of missing data).

High poverty area is defined as a census block group with 20% or greater of families living below the federal poverty level (n = 3,039 because of missing data).

n = 5,474 because of missing data.

African Americans were more likely than whites to have an IPCC (21.8% v 15.8%; P < .001). Although 20.0% of Hispanics received an IPCC compared with 15.8% of whites (P = .04), this did not meet the Bonferroni criterion for significance. African American patients were more likely than whites to be referred to hospice (15.9 v 11.0; P < .001). There were no significant differences in rates of hospice referral between Hispanics and either whites (P = .23) or African Americans (P = .20). There were no significant differences in neighborhood income or patients living in low-educational or high-poverty neighborhoods by race/ethnicity.

Table 2 displays sample characteristics for the patients who had an IPCC, stratified by race/ethnicity. Similar to our findings for the total sample, insurance status differed between whites and both African Americans and Hispanics; approximately 21% of African American and Hispanic patients had Medicaid insurance compared with 5% of whites, whereas only 23% of African Americans had private insurance compared with 48% of whites and 37% of Hispanics. Whites were more likely to be married than African Americans (55% v 30%; P < .001). There were no significant racial/ethnic differences in severity of illness, rates of DNR orders, or in-hospital death. Hospice referral differed between African American and Hispanic patients (59% v 41%, respectively; P = .006); no significant difference was found between African Americans or Hispanics and whites. The percentage of white, African American, and Hispanic patients with an IPCC at their first hospitalization (39% v 33% and 30%, respectively) did not differ significantly. African American patients had a higher median number of days from their first IPCC to death compared with whites (25 v 17 days; P = .006); there were no significant differences in median days to IPCC between Hispanics and whites (P = .58) or African Americans (P = .35).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients Who Received a Palliative Care Consult (n = 1,086)

| Characteristic | White (n = 682) | AA (n = 260) | Hispanic (n = 73) | P (AA v white)* | P (Hispanic v white)* | P (AA v Hispanic)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 61.4 (15.9) | 61.2 (14.9) | 53.2 (16.6) | .82 | < .001 | < .001 |

| Female, % | 51.6 | 66.2 | 63.0 | < .001 | .06 | .62 |

| Married, % | 55.1 | 29.6 | 41.1 | < .001 | .02 | .06 |

| Cancer type, %† | .011 | .22 | .010 | |||

| Lymph/heme | 21.5 | 13.4 | 25.7 | |||

| Breast | 10.0 | 13.0 | 15.7 | |||

| Noncolon GI | 12.7 | 11.0 | 15.7 | |||

| Lung | 11.9 | 17.9 | 4.3 | |||

| Colorectal | 6.9 | 9.8 | 4.3 | |||

| Other | 34.0 | 34.9 | 34.3 | |||

| Payor, % | < .001 | < .001 | .10 | |||

| Private insurance | 47.5 | 23.1 | 37.0 | |||

| Medicaid | 5.4 | 21.2 | 20.6 | |||

| Medicare | 44.7 | 51.2 | 38.4 | |||

| Other/unknown | 2.4 | 4.6 | 4.1 | |||

| APR severity of illness, % | ||||||

| 1 | 7.4 | 8.1 | 13.7 | .91 | .02 | .08 |

| 2 | 30.5 | 30.6 | 41.1 | |||

| 3 | 41.2 | 42.3 | 34.3 | |||

| 4 | 20.9 | 19.0 | 11.0 | |||

| DNR order, % yes | 73.5 | 69.6 | 64.4 | .24 | .10 | .40 |

| Palliative consult on first hospitalization, % yes‡ | 39.4 | 33.1 | 30.1 | .07 | .12 | .64 |

| Hospice referral, % yes | 51.2 | 59.2 | 41.1 | .03 | .10 | .006 |

| In-hospital death, % yes | 39.0 | 31.1 | 31.5 | .03 | .21 | .95 |

| Time to palliative consult, median, days§ | 44 (7-171) | 58 (6-212) | 91 (11-249) | .26 | .06 | .26 |

| Time from consult to death, median, days‖ | 17 (4-61) | 25 (5-145) | 18 (6-64) | .006 | .58 | .35 |

Abbreviations: AA, African American; APR, all-patient refined; DNR, do not resuscitate; lymph/heme, cancers of lymphatic and hematopoietic tissue; noncolon GI, GI cancers other than colorectal cancer.

P values were calculated using independent sample t tests for continuous variables, χ2 tests for categorical variables, and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for medians. The reported P values are based on pairwise comparisons among groups, and the significance level is based on Bonferroni-adjusted P < .017.

Type of cancer was based on International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, codes and was missing for 29 patients. The most frequent cancer types are presented. Lung cancer includes cancer of the lung and bronchus. See Appendix Table A2 for the breakdown of other types of cancer.

Percentage of patients who received a palliative care consult on their first hospitalization during the study period.

Median days from the first hospital admission during the study period to first palliative care consult.

Median days from the first palliative care consult to date of death (n = 885).

Factors Associated With IPCC

Results of the logistic regression analyses are shown in Table 3. In univariable analyses, African American and Hispanic patients had higher odds of receiving an IPCC than whites (odds ratio [OR], 1.49; 95% CI, 1.27 to 1.74; and OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.74, respectively). Compared with patients with private insurance, those with Medicaid or Medicare also had higher odds of IPCC (OR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.48 to 2.36; and OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.42, respectively). As illness severity increased, patients had an increasingly greater likelihood of receiving an IPCC, and patients who had at least one previous hospitalization had almost two-fold higher odds of IPCC than did those with a single hospitalization (OR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.68 to 2.19). After adjusting for illness severity, race/ethnicity, marital status, insurance, and number of hospitalizations, African American patients were still more likely to have an IPCC than whites (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.44). In the adjusted model, Medicaid patients also had higher odds of IPCC than patients with private insurance (OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.13 to 1.94). Unmarried patients had 1.29 higher odds of having an IPCC than married patients (95% CI, 1.22 to 1.50). In addition, patients had increasingly higher odds of IPCC with increasing illness severity (trend test P < .001). Patients who had multiple hospitalizations had two-fold higher odds of IPCC compared with those who did not (OR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.73 to 2.32).

Table 3.

Factors Associated With Inpatient Palliative Care Consultation for Patients With Advanced Cancer (N = 6,288)

| Variable | Unadjusted Analysis |

Adjusted Analysis* |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white (ref) | ||||

| African American | 1.49 | 1.27 to 1.74 | 1.21 | 1.01 to 1.44 |

| Hispanic | 1.33 | 1.01 to 1.74 | 1.20 | 0.90 to 1.59 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male (ref) | ||||

| Female | 0.90 | 0.79 to 1.03 | 1.00 | 0.86 to 1.15 |

| Age | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.01 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married (ref) | ||||

| Unmarried† | 1.43 | 1.26 to 1.64 | 1.29 | 1.22 to 1.50 |

| Insurance | ||||

| Private (ref) | ||||

| Medicaid | 1.87 | 1.48 to 2.36 | 1.48 | 1.13 to 1.94 |

| Medicare | 1.24 | 1.07 to 1.42 | 0.99 | 0.85 to 1.16 |

| Other | 0.92 | 0.63 to 1.36 | 0.92 | 0.61 to 1.39 |

| APR-DRG severity of illness | ||||

| 1 (ref) | ||||

| 2 | 2.00 | 1.56 to 2.58 | 1.81 | 1.40 to 2.35 |

| 3 | 3.97 | 3.10 to 5.08 | 3.39 | 2.63 to 4.37 |

| 4 | 7.55 | 5.73 to 9.95 | 7.26 | 5.44 to 9.69 |

| At least one prior hospitalization‡ | ||||

| No (ref) | ||||

| Yes | 1.92 | 1.68 to 2.19 | 2.00 | 1.73 to 2.32 |

NOTE. Results not displayed for patients of other racial/ethnic groups.

Abbreviations: APR-DRG, all-patient refined diagnosis-related group; OR, odds ratio; ref, reference.

Adjusted for race/ethnicity, insurance, severity of illness, number of hospitalizations, and marital status.

Patients who had more than one hospitalization during the study period and did not have a palliative consult on their first hospitalization.

Unmarried includes 49 patients with unknown and three patients with missing marital status.

Time to IPCC

Using Kaplan-Meier time-to-event analysis, we found that the median number of days from first admission to IPCC was shorter for African American patients than for whites (P < .001). Of African American patients, 25% received an IPCC by 246 days (Q1, lower quartile of the distribution) compared with 402 days (Q1) for whites and 286 days (Q1) for Hispanics. There were no significant differences between Hispanics and African Americans (P = .73) or whites (P = .10).

Survival Analysis

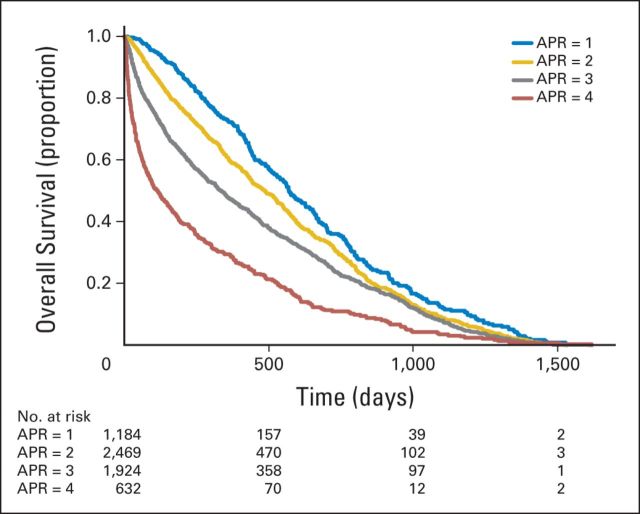

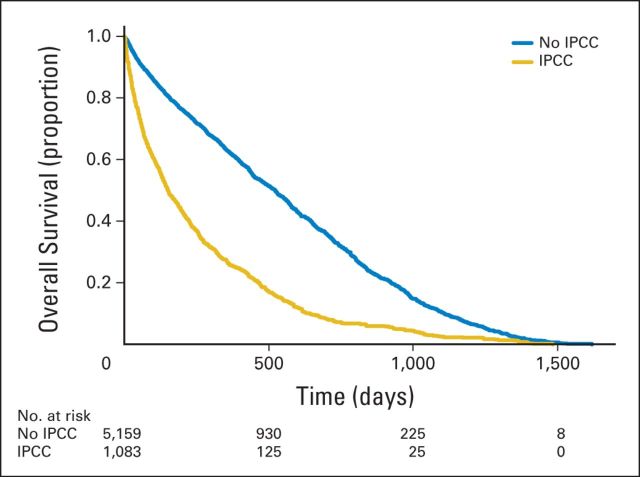

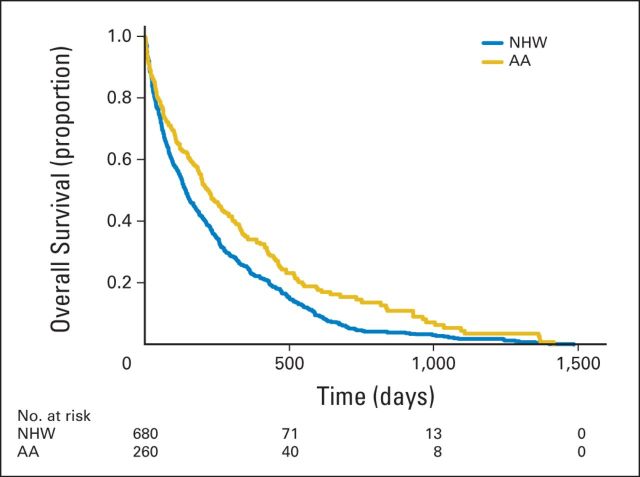

Kaplan-Meier estimates for time to death from admission did not differ significantly by race/ethnicity in the total sample (overall P = .19). Higher illness severity was associated with higher mortality rates (P < .001; Fig 1); patients with the highest level of severity (APR-DRG score of 4) had a median survival time of 116 days (95% CI, 88 to 149 days) compared with 570 days (95% CI, 521 to 641 days) for those with an APR-DRG score of 1. Median survival was lower for patients who had an IPCC (151 days; 95% CI, 136 to 174 days) than for patients who did not (523 days; 95% CI, 492 to 549 days; P < .001; Fig 2), independent of illness severity. Among patients who had an IPCC, whites had a shorter survival than African American (median survival, 141 v 221 days; P < .001; Fig 3) or Hispanic patients (median survival, 141 v 217 days; P = .015). Of whites, 25% died within 48 days of admission (95% CI, 38 to 57 days) versus 64 days for African Americans (95% CI, 43 to 94 days) and 98 days for Hispanics (95% CI, 50 to 142 days). After adjusting for illness severity and cancer type, only African American race remained a significant predictor of survival in patients who received an IPCC (hazard ratio, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.64 to 0.89; P < .001).

Fig 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival according to severity of illness (N = 6,242). Severity of illness was assessed by the all-patient refined diagnosis-related group (APR) complexity score, which ranges from 1 to 4, indicating minor to extreme severity. Time 0 (index date) is the patient's first hospitalization during the study period.

Fig 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival by receipt of inpatient palliative care consult (IPCC; N = 6,242). Time 0 (index date) is the patient's first hospitalization during the study period.

Fig 3.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival according to race for patients who received an inpatient palliative care consult (n = 940). Time 0 (index date) is the patient's first hospitalization during the study period. AA, African American; NHW, non-Hispanic white.

DISCUSSION

Although previous research has focused on racial/ethnic differences in hospice use,1–7 little is known about disparities in palliative care use, particularly in the hospital. We found that among patients hospitalized at an urban academic medical center, African American patients with metastatic disease were more likely than whites to receive an IPCC, even after adjusting for insurance status and illness severity. Furthermore, among patients who received an IPCC, African American patients were more likely than Hispanics, but not whites, to be referred to hospice. These findings suggest that inpatient settings may neutralize racial/ethnic differences in referral to hospice and palliative care services.

A previous study of critically ill patients found that physicians were more likely to document discord in discussions with families of nonwhite patients than with families of whites.30 Thus, one reason why African American patients in our study were more likely to receive an IPCC than whites may have been that physicians perceived greater discord between African American patients/families and physicians, and were thus more likely to seek assistance in discussing goals of care. Some physicians may also anticipate that their African American patients would be reluctant to discuss hospice given research findings that African American patients are more likely to prefer aggressive care at the end of life than whites,6,10,31–34 and, therefore, may obtain an IPCC to help with this difficult conversation.

Another explanation for our findings is that physicians consulted the palliative service primarily for discussion of hospice, believing that the additional services provided by hospice are especially beneficial for minority patients who they may perceive as having limited resources compared with their white counterparts. For the same reason, physicians may have been more likely to seek palliative care input for patients with Medicaid insurance, which uniformly provides coverage for hospice, than for those with private insurance; hence, the higher rates of IPCC for those patients. Our finding that no significant differences existed in IPCC rates between Hispanic and white patients after adjustment of insurance status seems to support this hypothesis.4 Higher rates of IPCC for African Americans, even after adjustment for insurance status, suggest that other factors may help explain why physicians are more likely to consult palliative care for these patients. Notably, our findings occurred in the context of racial/ethnic similarities in several neighborhood-level markers of socioeconomic status, allowing us to separate out the influence of race/ethnicity from socioeconomic status.

Our hospice referral rates for African American patients (59%) who had an IPCC mirror findings from a national study of Medicare decedents in which 54% of African American patients with cancer used hospice in their last year of life.3 However, in that study, 65% of white patients enrolled in hospice compared with 51% in our study. It is unclear whether our findings might reflect greater physician pursuit of aggressive care for whites with advanced disease compared with African Americans. We found no significant differences in survival by race/ethnicity in our total study sample; thus, any racial/ethnic differences in receipt of aggressive care do not seem to affect patient survival. Furthermore, our finding that among patients who had an IPCC, African American patients had a higher median level of survival than did white patients may suggest that physicians are delaying consults in white patients until patients are near death and/or that IPCC may help African American patients to live longer by emphasizing quality of life and minimizing burdensome treatments.15

Although African American patients in our sample were more likely than whites to receive an IPCC, less than 20% of the total sample received an IPCC, reflecting a need to increase rates of IPCC for patients regardless of race/ethnicity.35,36 Likewise, although the median time between first IPCC and death was longer for African American than for white or Hispanic patients (25 v 17 and 18 days, respectively), it was extremely short for all three groups. Our overall sample median time of 18 days between IPCC and death echoes findings from other institutions37 and represents a clear need for earlier access to palliative care for patients, irrespective of race/ethnicity.35,36,38 Finally, the association between IPCC and shorter survival for patients in our sample, in contrast with a study evaluating early integration of outpatient palliative care,15 likely reflects delayed initiation of palliative care for many patients in the hospital until they are at the end of life.

A few limitations are worth noting. First, data on race/ethnicity were abstracted from the medical record and may have under-represented the number of Hispanics and those who identify as multiracial. Second, we did not have data regarding reasons that motivated the physician to request an IPCC. Future research may be better able to identify racial/ethnic differences in the primary drivers of IPCC. Third, we did not have data on actual hospice enrollment rates because patients are typically enrolled after hospital discharge; thus, we could only abstract data on hospice referral. We also used text searching of the word “hospice” in case management notes as part of our identification of patients who were referred to hospice, which may have overestimated hospice referral rates. However, at our institution, case managers are typically involved in hospice discussions when the patient/family is interested in pursuing hospice, and most patients who are referred to hospice enroll in a hospice program after discharge. Next, we did not have data on the number of hospitalizations patients may have had before the study period. Finally, our findings reflect care at a single institution and may not be generalizable to other settings.

In conclusion, the hospital provides a critical window of opportunity for physicians to address the palliative care needs of minority patients, who are more likely than whites to receive hospital care in the last 6 months of life.39 Our finding that more than one half of the African American patients who receive an IPCC are referred for hospice suggests that IPCC may help overcome certain barriers to use of hospice services, including a lack of knowledge about palliative care and hospice, lack of exploration of patient values and goals, and mistrust of the medical establishment.40–43 Additional research is needed to develop interventions to increase rates of IPCC for patients with advanced cancer irrespective of race/ethnicity.

Appendix

Table A1.

ICD-9 Codes Used to Identify Study Sample

| ICD-9 Code* | Cancer Group |

|---|---|

| 196 | Secondary and unspecified malignant neoplasm of lymph nodes |

| 197 | Secondary malignant neoplasm of respiratory and digestive systems |

| 198 | Secondary malignant neoplasm of other specified sites |

Abbreviation: ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision.

Includes all subcodes as well.

Table A2.

Primary Cancer Type

| Cancer Type | CCS Code* | White (n = 4,062), % | African American (n = 1,089), % | Hispanic (n = 334), % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck | 11 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 0.9 |

| Esophagus | 12 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| Stomach | 13 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 2.4 |

| Colon | 14 | 4.6 | 7.4 | 5.1 |

| Rectum and anus | 15 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 2.1 |

| Liver and intrahepatic bile duct | 16 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 3.3 |

| Pancreas | 17 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 2.4 |

| Other GI organs and peritoneum | 18 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 3.0 |

| Bronchus and lung | 19 | 7.6 | 8.6 | 3.6 |

| Other respiratory/intrathoracic | 20 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 0 |

| Bone and connective tissue | 21 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 2.1 |

| Melanoma | 22 | 1.7 | 0.09 | 0 |

| Other nonepithelial skin cancer | 23 | 2.0 | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| Breast | 24 | 13.8 | 17.2 | 12.6 |

| Uterus | 25 | 2.0 | 3.9 | 3.0 |

| Cervix | 26 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0 |

| Ovary | 27 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| Other female genital organs | 28 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Prostate | 29 | 4.0 | 5.6 | 2.1 |

| Testis | 30 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.6 |

| Other male genital organs | 31 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 |

| Bladder | 32 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 0.6 |

| Kidney and renal pelvis | 33 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 3.6 |

| Other urinary organs | 34 | 0.15 | 0.2 | 0 |

| Brain and nervous system | 35 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 2.1 |

| Thyroid | 36 | 1.7 | 1.0 | 2.7 |

| Hodgkin disease | 37 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 3.0 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 38 | 9.7 | 7.0 | 12.9 |

| Leukemia | 39 | 8.4 | 4.5 | 8.4 |

| Multiple myeloma | 40 | 7.2 | 8.5 | 7.8 |

| Other and unspecified primary | 41 | 10.9 | 11.9 | 10.8 |

Abbreviation: CCS, Clinical Classification Software Codes.

CCS clusters International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis codes into broader categories of cancer type (additional details can be found at https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccsfactsheet.jsp).

Footnotes

Supported by the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University Director's Fund, and by Grant No. K12-HD055884 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R.K.S.). Funding for biostatistical consultation was provided via the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center's Core Support Grant, Biostatistics Core No. P30-CA060553 (J.S.C.).

Presented at the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA, March 12-15, 2014, and at the Society of General Internal Medicine 36th Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA, April 23-26, 2014.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Disclosures provided by the authors are available with this article at www.jco.org.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Rashmi K. Sharma, Jamie H. Von Roenn, Frank J. Penedo

Financial support: Rashmi K. Sharma

Collection and assembly of data: Rashmi K. Sharma

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Racial/Ethnic Differences in Inpatient Palliative Care Consultation for Patients With Advanced Cancer

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Rashmi K. Sharma

No relationship to disclose

Kenzie A. Cameron

Research Funding: MERCI (Medical Error Reduction and Certification) (Inst)

Joan S. Chmiel

No relationship to disclose

Jamie H. Von Roenn

No relationship to disclose

Eytan Szmuilowicz

No relationship to disclose

Holly G. Prigerson

No relationship to disclose

Frank J. Penedo

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Cohen LL. Racial/ethnic disparities in hospice care: A systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:763–768. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Virnig BA, Marshall McBean A, Kind S, et al. Hospice use before death: Variability across cancer diagnoses. Med Care. 2002;40:73–78. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connor SR, Elwert F, Spence C, et al. Racial disparity in hospice use in the United States in 2002. Palliat Med. 2008;22:205–213. doi: 10.1177/0269216308089305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lackan NA, Ostir GV, Freeman JL, et al. Hospice use by Hispanic and non-Hispanic white cancer decedents. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:969–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00267.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanchate A, Kronman AC, Young-Xu Y, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life costs: Why do minorities cost more than whites? Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:493–501. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wicher CP, Meeker MA. What influences African American end-of-life preferences? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23:28–58. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greiner KA, Perera S, Ahluwalia JS. Hospice usage by minorities in the last year of life: Results from the National Mortality Followback Survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:970–978. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weitzen S, Teno JM, Fennell M, et al. Factors associated with site of death: A national study of where people die. Med Care. 2003;41:323–335. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000044913.37084.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, et al. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:315–321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnato AE, Anthony DL, Skinner J, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in preferences for end-of-life treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:695–701. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0952-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodlin SJ, Zhong Z, Lynn J, et al. Factors associated with use of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in seriously ill hospitalized adults. JAMA. 1999;282:2333–2339. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith AK, Earle CC, McCarthy EP. Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life care in fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with advanced cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:153–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: Associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:480–488. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obermeyer Z, Makar M, Abujaber S, et al. Association between the Medicare hospice benefit and health care utilization and costs for patients with poor-prognosis cancer. JAMA. 2014;312:1888–1896. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Goldstein R. Ethnic differences in hospice enrollment following inpatient palliative care consultation. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:598–600. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Penrod JD, Deb P, Luhrs C, et al. Cost and utilization outcomes of patients receiving hospital-based palliative care consultation. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:855–860. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith TJ, Coyne P, Cassel B, et al. A high-volume specialist palliative care unit and team may reduce in-hospital end-of-life care costs. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:699–705. doi: 10.1089/109662103322515202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, et al. Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1783–1790. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.16.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norton SA, Hogan LA, Holloway RG, et al. Proactive palliative care in the medical intensive care unit: Effects on length of stay for selected high-risk patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1530–1535. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266533.06543.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson KS. Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:1329–1334. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.9468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiner MG, Livshits A, Carozzoni C, et al. Derivation of malignancy status from ICD-9 codes. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2003:1050. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright A, Pang J, Feblowitz JC, et al. A method and knowledge base for automated inference of patient problems from structured data in an electronic medical record. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18:859–867. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cowen ME, Dusseau DJ, Toth BG, et al. Casemix adjustment of managed care claims data using the clinical classification for health policy research method. Med Care. 1998;36:1108–1113. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199807000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Clinical Classification Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM Fact Sheet. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russell HV, Okcu MF, Kamdar K, et al. Algorithm for analysis of administrative pediatric cancer hospitalization data according to indication for admission. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14:88. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-14-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iezzoni LI, Ash AS, Shwartz M, et al. Predicting who dies depends on how severity is measured: Implications for evaluating patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:763–770. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-10-199511150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jean-Jacques M, Persell SD, Hasnain-Wynia R, et al. The implications of using adjusted versus unadjusted methods to measure health care disparities at the practice level. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26:491–501. doi: 10.1177/1062860611403135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muni S, Engelberg RA, Treece PD, et al. The influence of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status on end-of-life care in the ICU. Chest. 2011;139:1025–1033. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Degenholtz HB, Thomas SB, Miller MJ. Race and the intensive care unit: Disparities and preferences for end-of-life care. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:S373–S378. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000065121.62144.0D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garrett JM, Harris RP, Norburn JK, et al. Life-sustaining treatments during terminal illness: Who wants what? J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:361–368. doi: 10.1007/BF02600073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blackhall LJ, Frank G, Murphy ST, et al. Ethnicity and attitudes towards life sustaining technology. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:1779–1789. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mebane EW, Oman RF, Kroonen LT, et al. The influence of physician race, age, and gender on physician attitudes toward advance care directives and preferences for end-of-life decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:579–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb02573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Institute of Medicine. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamal AH, Swetz KM, Carey EC, et al. Palliative care consultations in patients with cancer: A Mayo Clinic 5-year review. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:48–53. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osta BE, Palmer JL, Paraskevopoulos T, et al. Interval between first palliative care consult and death in patients diagnosed with advanced cancer at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:51–57. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baicker K, Chandra A, Skinner JS, et al. Who you are and where you live: How race and geography affect the treatment of Medicare beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood) doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.var.33. 10.1377/hlthaff.var.33 [epub ahead of print October 2004] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwak J, Haley WE. Current research findings on end-of-life decision making among racially or ethnically diverse groups. Gerontologist. 2005;45:634–641. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.5.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Tulsky JA. What explains racial differences in the use of advance directives and attitudes toward hospice care? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1953–1958. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01919.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laguna J, Enguidanos S, Siciliano M, et al. Racial/ethnic minority access to end-of-life care: A conceptual framework. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2012;31:60–83. doi: 10.1080/01621424.2011.641922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sacco J, Deravin Carr DR, Viola D. The effects of the palliative medicine consultation on the DNR status of African Americans in a safety-net hospital. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2013;30:363–369. doi: 10.1177/1049909112450941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]