Abstract

Purpose

To determine the developmental trajectory of early cognitive and adaptive skills in young children with retinoblastoma from diagnosis to 5 years of age.

Patients and Methods

Ninety-four patients with retinoblastoma treated according to an institutional protocol underwent serial assessments of cognitive and adaptive functioning at age 6 months and 1, 2, 3, and 5 years. Data were analyzed by treatment strata, with patients with 13q deletion analyzed separately.

Results

At baseline, across all patients (except those with 13q deletion), developmental functioning was comparable with the normative mean, with mean scores for all strata within the average range. However, at age 5 years, developmental functioning was in the low average range and significantly below normative means. The trajectories of developmental functioning demonstrated significant decline over time, although this varied by treatment group/strata. Patients treated with enucleation only evidenced the greatest decline in cognitive functioning; significant change was not observed in patients treated with other modalities. Notable declines in parent-reported communication skills were observed in the majority of patients. Patients with 13q deletion evidenced delayed cognitive functioning at baseline, but minimal declines were observed through age 3 years. However, significant decreases in adaptive functioning were demonstrated over time for the 13q deletion subset.

Conclusion

The declines in functioning observed in this study were unexpected, as was the poorer performance of the enucleation-only group. This highlights the necessity of continuing to assess cognitive functioning in patients with retinoblastoma as they age. Additional research is necessary to determine the long-term trajectory of cognitive development in this population.

INTRODUCTION

Retinoblastoma is an ocular cancer typically diagnosed in children younger than 2 years.1,2 Standard treatment may include chemotherapy, focal therapy, radiation, and/or enucleation.1 Decisions regarding treatment take into account prognosis for vision, laterality of disease, age of the child, size and location of the tumor, and potential for metastatic spread.2 Survival rates are high; however, morbidity with respect to vision loss is frequent,3 with degree of impairment varying by tumor burden/location and treatment modality.4,5

Early studies of intellectual functioning in children with retinoblastoma suggested that survivors demonstrated above-average intellectual functioning when compared with the general population or unaffected siblings.6–8 Such findings were particularly true of children whose disease was associated with blindness.6,8 However, these few early studies are quite old and have several methodological limitations, particularly ascertainment bias. In contrast, more recent reports have suggested that cognitive functioning after diagnosis and treatment of retinoblastoma is within the average to above-average range and similar to that for same-age peers.5,9,10 Notably, there are variations in cognitive performance, particularly with regard to age at diagnosis, disease location (unilateral v bilateral), and treatment modality.9 Children treated before the age of 3 months, those with unilateral disease, and those treated with radiation therapy at a young age performed significantly worse than their counterparts.5 In addition, an estimated 5% to 10% of patients with retinoblastoma will have an interstitial 13q chromosomal deletion.11 These patients have been noted to have neurologic impairments and are at high risk for intellectual disability,12,13 and thus have typically been excluded in prior studies of cognitive outcomes.

To date, the available studies have relied on observations of children who were several years post-treatment5,9 or consisted of cross sectional assessments at only one point in time,9,10 thus limiting the conclusions that can be made regarding potential change in functioning over time. Thus, the early developmental trajectory of these children, who were diagnosed and treated during infancy and toddlerhood, remains unknown. As such, the objective of the current study was to determine the developmental trajectory of early cognitive and adaptive skills in young children with retinoblastoma from diagnosis to age 5 years.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Population

Pediatric patients with newly diagnosed retinoblastoma were evaluated as part of their enrollment on an institutional treatment protocol.14 Patients were stratified by disease group (by using Reese-Ellsworth [RE] classification15) and laterality (unilateral or bilateral), with multimodal therapy including chemotherapies, focal therapies, and/or enucleation. Patients with progressive disease were considered for external-beam radiation therapy. Patients on stratum A (unilateral or bilateral RE I to III) and stratum B (RE IV to V bilateral) received neoadjuvant chemotherapy by using a variety of agents. Therapy for patients on stratum C (RE IV to V unilateral) with upfront enucleation was stratified by risk on the basis of pathologic examination of enucleated eyes, with low-risk patients receiving observation only, intermediate-risk patients receiving four cycles of chemotherapy postenucleation, and high-risk patients receiving six cycles of chemotherapy postenucleation and external-beam radiation therapy if needed. Although patients were receiving antineoplastic therapy, they also received occupational and speech therapy services as well as routine functional assessments of hearing and other organ function. A more detailed description of the patient population and treatment modalities has been presented elsewhere.14

Of patients enrolled onto the institutional treatment protocol, 94 patients (83.2%) completed serial assessments. Eligibility criteria for the developmental assessment portion included English as the primary language spoken in the home and younger than age 5 years at diagnosis. Patients who did not complete cognitive testing were older at diagnosis (P = .012) and more likely to be non–African American minorities (P = .002); there were no other significant differences. Demographic and diagnosis information is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and Diagnostic Information for the 94 Patients Included in Analyses

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, years | ||

| Mean | 1.29 | |

| SD | 1.12 | |

| Median | 0.82 | |

| Range | 0.03-5.61 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 48 | 51.06 |

| Female | 46 | 48.94 |

| Race | ||

| White | 63 | 67.02 |

| African American | 22 | 23.40 |

| Multiple race | 3 | 3.19 |

| Other | 6 | 6.38 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Bilateral* | 35 | 37.23 |

| Bilateral (asynchronous) | 6 | 6.38 |

| Left eye | 29 | 30.85 |

| Right eye | 24 | 25.53 |

| Strata | ||

| A | 16 | 17.02 |

| B | 23 | 24.47 |

| C low | 30 | 31.91 |

| C high | 15 | 15.96 |

| 13q deletion | 10 | 10.64 |

| No. of assessments | ||

| Mean | 2.96 | |

| SD | 1.16 | |

| Range | 1-5 | |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

One patient with bilateral disease (stratum B) eventually underwent a bilateral enucleation. This patient provided two assessments after his first enucleation. They completed no additional assessments after the second enucleation.

Procedures and Measures

Serial psychometric assessments were scheduled primarily on the basis of patient age rather than time from study entry and/or treatment completion. Patients were eligible for an evaluation at time of study entry, age 6 months, and 1, 2, 3, and 5 years. As such, the number of assessments completed by each patient varied by age at diagnosis (Table 2). At each time point, patients were administered the Mullen Scales of Early Learning.16 This assessment tool is designed to measure cognitive functioning of infants and young children from birth through age 68 months. The Mullen Scales assesses a child's ability to function across a variety of domains, including gross and fine motor skills, receptive and expressive language, and visual reception. Four scales (all but gross motor) combine to yield an Early Learning Composite. Parents completed the Vineland Scales of Adaptive Behavior, Interview Edition.17 This instrument provides a reliable and valid measure of relevant daily living skills of a developing child. Administered via semistructured interview, the Vineland provides scores in four domains: communication, daily living skills, socialization, and motor skills, as well as an overall adaptive behavior composite.

Table 2.

Assessment Time Points for the 94 Patients Included in Analyses

| Assessment Time Points* | Assessments Completed N | Months Since Diagnosis |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | ||

| 6 months old | 36 | 1.36 | 1.74 |

| 1 year old | 57 | 4.82 | 3.54 |

| 2 years old | 70 | 12.9 | 6.73 |

| 3 years old | 72 | 20.26 | 10.60 |

| 5 years old | 38 | 38.34 | 16.60 |

Abbreviations: M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

An additional five assessments were completed at baseline (ie, shortly after the patient's diagnosis but greater than ± 3 months from a scheduled assessment age).

Measures were chosen to provide both objective (Mullen) and subjective (Vineland) assessment of the child's functioning. Multimethod assessment batteries are considered the standard of care,18 with performance-based measures as well as parent-report measures typically involved. Moreover, these measures were chosen because they encompassed the entire age range of the sample (0 to 5 years).

Statistical Analyses

Patients with a 13q deletion (n = 10), regardless of strata, were analyzed separately as a result of the increased risk of cognitive delays associated with this deletion.12,13 The remaining patients were then grouped across four strata, on the basis of treatment protocol, and analyses were completed to compare both between and within strata: stratum A, B, C low, and C high. Patients who were in stratum C and determined to be either intermediate or high risk (enucleation plus chemotherapy) were combined into the stratum C high group. Stratum C low patients received enucleation only.

At baseline and age 5 years, mean scores for all indices were compared with published normative means via one-sample t tests. Longitudinal trends by using assessments at all ages were first analyzed for the entire group and then separately for each stratum by using linear mixed-effect models and evaluated to account for the effect of patient age. Specifically, slopes were estimated for each index for the whole group and for each stratum.

RESULTS

Developmental Functioning

At baseline, the mean Early Learning Composite for all patients (with exception of patients with 13q deletion) was comparable with the normative mean [t(46) = −1.86, P = .069; Table 3], with mean scores for all strata within the average range. Although this trend was similar across all individual subscales, with mean scores within the average range, mean scores were significantly less than the normative mean on gross motor skills, expressive language, and receptive language (Table 2). In contrast, at age 5 years, the mean score on the Early Learning Composite was in the low average range and significantly less than the normative mean [t(32) = −6.07, P < .001]. This was generally true for all subscales, with the exception of visual reception, which remained within the average range at age 5 years (Table 2).

Table 3.

Baseline and Year 5 Scores for All Patients Compared With Normative Means (n = 84)

| Score | Baseline |

Age 5 Years |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | t* | P | M | t* | P | |

| Mullen Scales of Early Learning† | ||||||

| Early learning composite | 95.74 | −1.86 | .069 | 84.03 | −6.07 | < .001 |

| Fine motor skills | 51.04 | 0.51 | NS | 39.97 | −4.84 | < .001 |

| Receptive language | 44.37 | −3.37 | .002 | 40.58 | −4.93 | < .001 |

| Expressive language | 46.12 | −2.74 | .009 | 40.18 | −5.37 | < .001 |

| Visual reception | 47.12 | −1.62 | NS | 44.29 | −3.47 | .002 |

| Gross motor skills‡ | 45.14 | −3.24 | .002 | — | — | — |

| Vineland Scales of Adaptive Behavior§ | ||||||

| Adaptive behavior composite | 106.8 | 5.02 | < .001 | 96.43 | −1.44 | NS |

| Communication | 105.5 | 3.90 | .003 | 91.9 | −4.32 | .001 |

| Daily living skills | 106.4 | 3.41 | .001 | 100.7 | 0.28 | NS |

| Socialization | 110.4 | 10.13 | < .001 | 102.1 | 1.00 | NS |

| Motor skills | 98.71 | −1.17 | NS | 94.39 | −1.53 | NS |

NOTE. Patients included from strata A, B, C low, and C high.

Abbreviations: M, mean; NS, not significant; SD, standard deviation.

One-sample t tests compared patient performance with normative means.

Early Learning Composite: normative mean, 100; SD, 15. Subscales: normative mean, 50; SD, 10.

Only available through 3 years of age.

All scales: normative mean, 100; SD, 15.

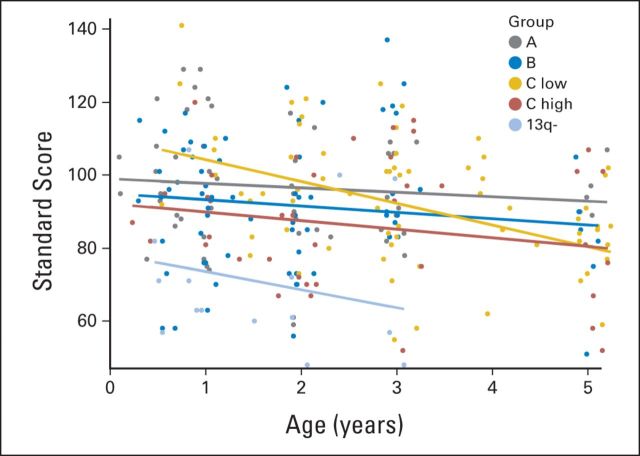

Longitudinally, performance on the Mullen declined significantly over time (Table 4). However, the slope of change demonstrated significant variability among strata and across subscales. Specifically, for the Early Learning Composite, stratum C low patients evidenced a significant decline over time, such that the change in slope was significantly different than 0 (estimate = −5.97, t = −3.74, P = .001; Fig 1). All other strata showed no significant changes over time. This same pattern of a significant decline over time only in patients in stratum C low was also observed for the visual reception, receptive language, and expressive language subscales. In contrast, on fine motor skills, a significant decline over time was observed in patients from all strata.

Table 4.

Longitudinal Trajectory of the Primary Outcome Measures (n = 84)

| Outcome | Estimate | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mullen Scales of Early Learning | |||

| Early learning composite | −2.8774 | −3.62 | .001 |

| Fine motor skills | −2.5724 | −4.88 | < .001 |

| Receptive language | −1.3880 | −2.80 | .006 |

| Expressive language | −1.2646 | −2.56 | .012 |

| Visual reception | −0.7753 | −1.37 | NS |

| Gross motor skills* | −1.2655 | −0.95 | NS |

| Vineland Scales of Adaptive Behavior | |||

| Adaptive behavior composite | −2.6029 | −5.98 | < .001 |

| Communication | −2.9110 | −5.97 | < .001 |

| Daily living skills | −1.7779 | −2.74 | < .001 |

| Socialization | −1.8939 | −3.74 | < .001 |

| Motor skills | −1.0082 | −1.74 | NS |

NOTE. Patients included from strata A, B, C low, and C high. Repeated measures linear mixed modeling to estimate longitudinal trajectory. Estimate reflects change per year; P value reflects significance of change from an expected slope of 0.

Abbreviation: NS, not significant.

Only available through 3 years of age.

Fig 1.

Longitudinal trajectory of the Early Learning Composite, delineated by strata.

Adaptive Functioning

At age 6 months, parent report of adaptive functioning via the Adaptive Behavior Composite was greater than the normative mean, although within the average range. This was true of all subscales, with the exception of motor skills, which was no different than the normative mean (Table 2). At age 5 years, adaptive behavior scores remained within the average range but were no longer significantly different from the normative mean. The exception was parent report of communication skills, which was significantly less than the normative mean, although within the average range.

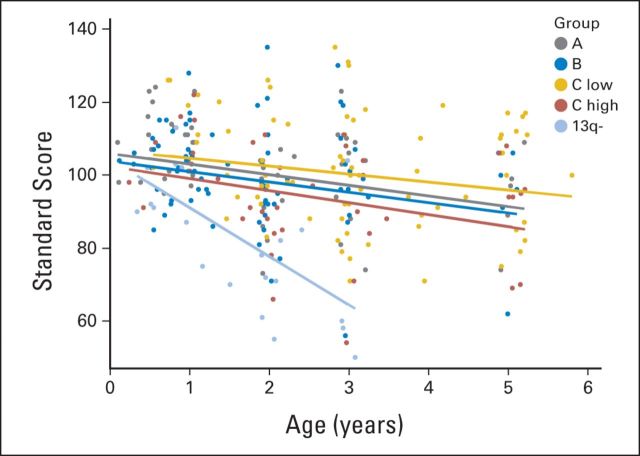

Longitudinally, the trajectory of adaptive functioning declined significantly over time (Table 4). However, the slope of decline varied significantly by strata (Fig 2). In general, the adaptive functioning of stratum C low patients was relatively stable through age 5 years. In contrast, significant declines in trajectory were observed in parent report of communication and daily living skills for patients in strata A and B and in communication, socialization, and motor skills for patients in stratum C high.

Fig 2.

Longitudinal trajectory of the Adaptive Behavior Composite, delineated by strata.

Patients With 13q Deletion

Given the known risk of cognitive delays associated with 13q deletion,12,13 these patients (n = 10) were analyzed separately. In addition, data were not available for these patients after age 3 years as a result of the ongoing nature of this treatment-based study.

At baseline, mean scores on the Early Learning Composite were significantly below the normative mean and within the borderline range of functioning (Table 5). This pattern of low functioning at baseline was true for all subscales, although there was some variability, with scores ranging from extremely low (expressive language) to low average (visual reception). In contrast, at baseline, parent ratings of adaptive behavior were much stronger, ranging from low average (motor skills) to average (all other indices).

Table 5.

Baseline Scores for Patients With13q Deletion

| Score | M | t | P | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mullen Scales of Early Learning* | ||||

| Early learning composite | 72.8 | −3.11 | .04 | Borderline |

| Fine motor skills | 32.8 | −3.37 | .02 | Borderline |

| Receptive language | 31.3 | −4.27 | .008 | Borderline |

| Expressive language | 29.0 | −3.78 | .01 | Extremely low |

| Visual reception | 37.5 | −2.16 | .08 | Low average |

| Gross motor skills | 28.3 | −4.25 | .008 | Extremely low |

| Vineland Scales of Adaptive Behavior† | ||||

| Adaptive behavior composite | 91.7 | −1.19 | NS | Average |

| Communication | 94.0 | −1.19 | NS | Average |

| Daily living skills | 95.8 | −0.50 | NS | Average |

| Socialization | 102.2 | 0.34 | NS | Average |

| Motor skills | 82.7 | −3.48 | .02 | Low average |

NOTE. One-sample t tests compared performance with normative means.

Abbreviations: M, mean; NS, not significant; SD, standard deviation.

Early Learning Composite: normative mean, 100; SD, 15. Subscales: normative mean, 50; SD, 10.

All scales: normative mean, 100; SD, 15.

Although baseline functioning was low, the scores of patients with 13q deletion on the Mullen did not continue to decline over 3 years. The slopes of the lines for all indices—early learning composite and individual subscales—were not significantly different from 0, suggesting relative stability in developmental functioning through age 3 years. In contrast, parent-reported adaptive functioning declined significantly over 3 years. Specifically, the slope of decline for the adaptive behavior composite was significantly different from zero (estimate = −13.36, t = −5.44, P < .001; Fig 2). A similar pattern emerged for all subscales, including communication, daily living skills, socialization, and motor skills, with significant declines in all areas of adaptive functioning during the course of study.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the longitudinal trajectory of developmental functioning of infants and young children with retinoblastoma through their first 5 years of life. In contrast with the majority of previous research, at age 5 years, patients with retinoblastoma (excluding those with 13q deletion) demonstrated developmental functioning in the low-average range, significantly less than what would be expected on the basis of population means. Moreover, this represented a significant decline over time. A significant decline was also observed in the trajectory of parent ratings of adaptive functioning; however, scores at age 5 years remained within the average range.

The significant decline in functioning was unexpected in light of past research, in which cross-sectional studies of retinoblastoma survivors suggest cognitive functioning within the average to high-average range.5,9,10 This highlights the necessity of continuing to assess cognitive functioning in patients with retinoblastoma as they age. Early childhood is a time of considerable cognitive growth and variability. Continued prospective assessment of this patient population is warranted and will benefit from incorporation of more reliable assessments for older children to address the final outcome of this early functional decline.

Patients with 13q deletion syndrome demonstrated delays in baseline developmental functioning with scores generally falling within the borderline range. Over time (3 years as a result of the ongoing nature of this prospective treatment study), there was relative stability in developmental functioning performance, although parent ratings of adaptive functioning declined significantly. These results are generally commensurate with limited past research that suggests that patients with 13q deletion are at high risk for cognitive dysfunction.12,13 Given that most patients with 13q deletion were diagnosed with this abnormality after the diagnosis of retinoblastoma, it is possible that the decline in parental assessment is linked to their newfound knowledge of this syndrome.

All patients (all strata) had declines noted in fine motor skills. Although patients with retinoblastoma have known difficulty with visuomotor integration, the decline in visually mediated skills (eg, visual reception and fine motor skills) is difficult to explain in a population that did not lose vision during therapy, but likely had disease-related loss of vision from early infancy. Because this is the first prospective evaluation of this population, we may have identified areas of lower functioning than known previously. This presents a critical area for timely intervention.

Aside from 13q deletion, the subgroup with the greatest decline in functioning across all subscales and over time was stratum C low. Although enucleation has been suggested as a risk factor for lower functioning in prior studies,5 the magnitude of decline as compared with other strata is striking, particularly given that patients in stratum C low received no additional treatment (in contrast with all other strata), and the remaining eye for patients with unilateral disease is expected to have normal visual potential. This finding is particularly intriguing when patients in stratum C low are compared with patients in stratum C high. Specifically, the only medical intervention that differs between these two groups is the addition of chemotherapy in patients in stratum C high; yet the longitudinal trajectories of these two groups are quite different.

Our understanding of the cause of cognitive risks in patients treated with enucleation only is limited. However, there are some reasonable, albeit speculative, hypotheses as to why these surgery-only patients exhibit greater cognitive declines than their more intensely treated peers. Routine guidance and instructions to protect the eye(s) are given to all patients diagnosed with retinoblastoma. It is possible that for patients who undergo enucleation only and do not receive additional intervention other than ocular examinations, such instructions cause parents to restrict the environment of their children to preserve their remaining eye (fragile child syndrome). This, in turn, may reduce exposure to the learning experiences these young children need to fully develop. Moreover, these patients may be less likely to be enrolled onto the comprehensive rehabilitation services (physical, occupational, and/or speech therapy) that are afforded to patients who remain closely connected to a hospital for additional treatment. The combination of a restrictive environment coupled with lack of rehabilitation services may be particularly damaging during the plasticity of early childhood, particularly for the types of skills assessed via a developmental assessment–a phenomenon that has been observed in premature infants.19 A recent study found that patients with bilateral as opposed to unilateral retinoblastoma were more likely to be referred for rehabilitation services.10 If this same pattern is true in this cohort, this may help to explain the declines observed in patients with unilateral disease (strata C low and C high). Finally, it is certainly possible that the declines observed represent only a statistical regression to the mean; findings must be replicated to rule out this possibility.

It is notable that the greatest declines observed across strata were in language-based skills, and in particular, expressive language. Because patients also had mean scores less than the normative mean on language tasks at baseline, this study suggests a population in need of early language intervention. It is possible that if we were to continue to complete serial assessments of these patients as they mature to school age and beyond that, the patients who had enucleation may begin to resemble their two-eyed counterparts. Additional research is necessary to answer these questions and to determine the long-term trajectory of cognitive development in patients with retinoblastoma. It will also be important to examine aspects of quality of life and daily living to determine the functional effect of enucleation and associated vision loss. A recent study suggested that survivors of bilateral retinoblastoma demonstrated limited involvement in daily activities and associated poor emotional quality of life, and that patients with a history of enucleation reported particularly poor self-esteem.20

The current data originate from a prospective, treatment-directed study, which is closed to accrual but with ongoing follow-up. Thus, a limitation is that the long-term outcomes are based on smaller numbers than are available for baseline performance. In addition, because the majority of patients who did not complete study-related assessments were older, it is possible that a higher percentage of patients with unilateral retinoblastoma (likely with enucleation) were excluded. Similarly, given that our study design depended on age for entry into cognitive assessment, we could not stratify results by age as a proxy for time of exposure to rehabilitative therapy. Future studies should document participation in rehabilitation services more concretely. Another potential limitation is our reliance on developmental assessments as a result of the age range surveyed and the absence of a more sophisticated and comprehensive cognitive battery. The validity of early developmental assessments for predicting later cognitive outcomes has been subject to debate.21,22 However, recent research has suggested good convergent validity of the Mullen and other tests of cognitive functioning in clinical populations.23 As this cohort ages, future studies will incorporate expanded assessments of cognitive and academic functioning to more clearly determine the functional effect of retinoblastoma diagnosis and treatment. A final limitation is the single-site nature of this study, which may constrain generalization, particularly with regard to cultural background or socioeconomic status. With these data, our patient population comes from a wide variety of socioeconomic statuses, geographic locations, and cultural backgrounds. However, given that this is the first known study to prospectively follow the developmental functioning of young patients with retinoblastoma, and in light of the significant findings, we felt they merited report at this time.

In summary, the current results demonstrate a decline in the developmental functioning of patients treated in infancy or toddlerhood for retinoblastoma. Curiously, this decline occurs most significantly in those patients treated with enucleation only, who receive no additional antineoplastic therapies. The lack of additional therapeutic intervention may extend to a reduced exposure to rehabilitative services. Additional longitudinal study is needed to examine mechanisms and to assess whether such declines continue over time, level off, or lead to subsequent recovery. A recent multisite study suggested that enucleation of a high-grade unilateral retinoblastoma, with or without adjuvant chemotherapy, is associated with complete, event-free survival through 5 years postdiagnosis.24 Although these outcomes with regard to the quantity of life that is afforded to these patients are promising, they raise concern regarding the subsequent quality of life, particularly if such treatments are associated with significant cognitive decline that could be ameliorated with appropriate early intervention.

Acknowledgment

We thank Bryan Winter, Department of Biostatistics at St Jude Children's Research Hospital, for his assistance with analyses.

Footnotes

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Ibrahim Qaddoumi, Carlos Rodriguez-Galindo, Matthew W. Wilson, Sean Phipps

Collection and assembly of data: Ibrahim Qaddoumi, Sean Phipps

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Shields CL, Shields JA. Retinoblastoma management: Advances in enucleation, intravenous chemoreduction, and intra-arterial chemotherapy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010;21:203–212. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e328338676a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ray A, Gombos DS, Vats TS. Retinoblastoma: An overview. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79:916–921. doi: 10.1007/s12098-012-0726-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epelman S. Preserving vision in retinoblastoma through early detection and intervention. Curr Oncol Rep. 2012;14:213–219. doi: 10.1007/s11912-012-0226-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Narang S, Mashayekhi A, Rudich D, et al. Predictors of long-term visual outcome after chemoreduction for management of intraocular retinoblastoma. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2012;40:736–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2012.02757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ek U, Seregard S, Jacobson L, et al. A prospective study of children treated for retinoblastoma: Cognitive and visual outcomes in relation to treatment. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2002;80:294–299. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2002.800312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levitt EA, Rosenbaum AL, Willerman L, et al. Intelligence of retinoblastoma patients and their siblings. Child Dev. 1972;43:939–948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eldridge R, O'Meara K, Kitchin D. Superior intelligence in sighted retinoblastoma patients and their families. J Med Genet. 1972;9:331–335. doi: 10.1136/jmg.9.3.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams M. Superior intelligence of children blinded from retinoblastoma. Arch Dis Child. 1968;43:204–210. doi: 10.1136/adc.43.228.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nahum MP, Gdal-On M, Kuten A, et al. Long-term follow-up of children with retinoblastoma. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;18:173–179. doi: 10.1080/08880010151114769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross G, Lipper EG, Abramson D, et al. The development of young children with retinoblastoma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:80–83. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bunin GR, Emanuel BS, Meadows AT, et al. Frequency of 13q abnormalities among 203 patients with retinoblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:370–374. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.5.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baud O, Cormier-Daire V, Lyonnet S, et al. Dysmorphic phenotype and neurological impairment in 22 retinoblastoma patients with constitutional cytogenetic 13q deletion. Clin Genet. 1999;55:478–482. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.1999.550614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ballarati L, Rossi E, Bonati MT, et al. 13q Deletion and central nervous system anomalies: Further insights from karyotype-phenotype analyses of 14 patients. J Med Genet. 2007;44:e60–e65. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.043059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qaddoumi I, Billups CA, Tagen M, et al. Topotecan and vincristine combination is effective against advanced bilateral intraocular retinoblastoma and has manageable toxicity. Cancer. 2012;118:5663–5670. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reese AB, Ellsworth RM. The evaluation and current concept of retinoblastoma therapy. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1963;67:164–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mullen EM. Mullen Scales of Early Learning. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Services; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sparrow SS, Balla D, Cicchetti D. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Services; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sattler JM. Assessment of children: Cognitive Applications (ed 4) San Diego, CA: Jerome M. Sattler; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bao X, Sun S, Wei S. Early intervention promotes intellectual development of premature infants: A preliminary report—Early Intervention of Premature Infants Cooperative Research Group. Chin Med J. 1999;112:520–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weintraub N, Rot I, Shoshani N, et al. Participation in daily activities and quality of life in survivors of retinoblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56:590–594. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aylward GP. Conceptual issues in developmental screening and assessment. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1997;18:340–349. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199710000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bradley-Johnson S. Cognitive assessment for the youngest children: A critical review of tests. J Psychoeduc Assess. 2001;19:19–44. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bishop SL, Guthrie W, Coffing M, et al. Convergent validity of the Mullen Scales of Early Learning and the differential ability scales in children with autism spectrum disorders. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2011;116:331–343. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-116.5.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aerts I, Sastre-Garau X, Savignoni A, et al. Results of a multicenter prospective study on the postoperative treatment of unilateral retinoblastoma after primary enucleation. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1458–1463. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.3962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]