Abstract

The perception of two plant germination inducers, karrikins and strigolactones, are mediated by the proteins KAI2 and D14. Recently, KAI2-type proteins from parasitic weeds, which are possibly related to seed germination induced by strigolactone, have been classified into three clades characterized by different responses to karrikin/strigolactone. Here we characterized a karrikin-binding protein in Striga (ShKAI2iB) that belongs to intermediate-evolving KAI2 and provided the structural bases for its karrikin-binding specificity. Binding assays showed that ShKAI2iB bound karrikins but not strigolactone, differing from other KAI2 and D14. The crystal structures of ShKAI2iB and ShKAI2iB-karrikin complex revealed obvious structural differences in a helix located at the entry of its ligand-binding cavity. This results in a smaller closed pocket, which is also the major cause of ShKAI2iB’s specificity of binding karrikin. Our structural study also revealed that a few non-conserved amino acids led to the distinct ligand-binding profile of ShKAI2iB, suggesting that the evolution of KAI2 resulted in its diverse functions.

Strigolactones (SLs) are originally isolated as germination stimulants for parasitic weeds Striga and Orobanche genera1, which are among the most severe threats for agricultural production in sub-Saharan Africa2. Later, it has been proved that SLs also act as symbiotic signals by triggering hyphal branching of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi3, and as endogenous phytohormone by inhibiting lateral branching4,5. In addition to SLs, karrikins6,7, which are abiotic butenolide derived from burning vegetation, can also induce seed germination after forest fires8. Interestingly, these two distinct classes of germination stimulus, SLs and karrikins, adopt similar structures sharing a common lactone ring, which is supposed to be vital for signal perception9.

SL receptor D14 (DWARF14) and karrikin-responding protein KAI2 (KARRIKIN INSENSITIVE 2) are closely related homologues belonging to α/β hydrolases superfamily. Another convergent point of these two classes of proteins is that they both need the F-box protein, MAX2 (MORE AXILLARY GROWTH2)10 or D3 (DWARF3) in Oryza sativa11, for signal transduction through direct12,13,14 or indirect interaction15. Despite the fact that D14 and KAI2 share a lot in common, they have different functions and play distinct roles in regulation of plant growth. D14 proteins are verified to be capable of binding and hydrolyzing GR24 (synthetic SL analogue) with conserved catalytic triad residues (Ser-His-Asp). In contrast, KAI2 protein is able to bind both GR24 and karrikin and shows hydrolytic activity toward GR2416, while no detectable hydrolytic activity toward karrikin has been reported so far. Besides, D14 is mainly involved in inhibiting axillary bud outgrowth through perception of SLs while KAI2 is required for seed germination by perception of karrikins and/or exogenous SLs and for early seedling development by mediating responses to SL17.

This raised questions about how these two highly similar proteins show different patterns of ligand perception. Recently, KAI2 paralogs from parasitic weeds have been phylogenetically classified into three clades (ancestral, intermediate- and fastest-evolving KAI2) with different responses to karrikin/SL18,19 (Supplementary Figure S1). Ancestral/conserved clade is most conserved to KAI2 phylogenetically but nonresponsive to neither karrikin nor SL; diverse/fastest-evolving clade is corresponding to D14 being responsive to SL but not karrikin; while intermediate clade is responsive to karrikin but not SL. Since crystal structures of KAI2 and D14 have already been reported12,20,21,22,23,24,25, the structural study of KAI2 of intermediate clade would deepen our understanding of the molecular mechanism underlying these ligand-binding specificities. Here we present the crystal structure of S. hermonthica intermediate KAI2 (ShKAI2iB), which has 98% sequence identity with ShKAI2i (Supplementary Figure S2) that has been reported to respond to karrikin but not to GR24 through complementation experiments18.

Results

Ligand-binding specificity of ShKAI2iB

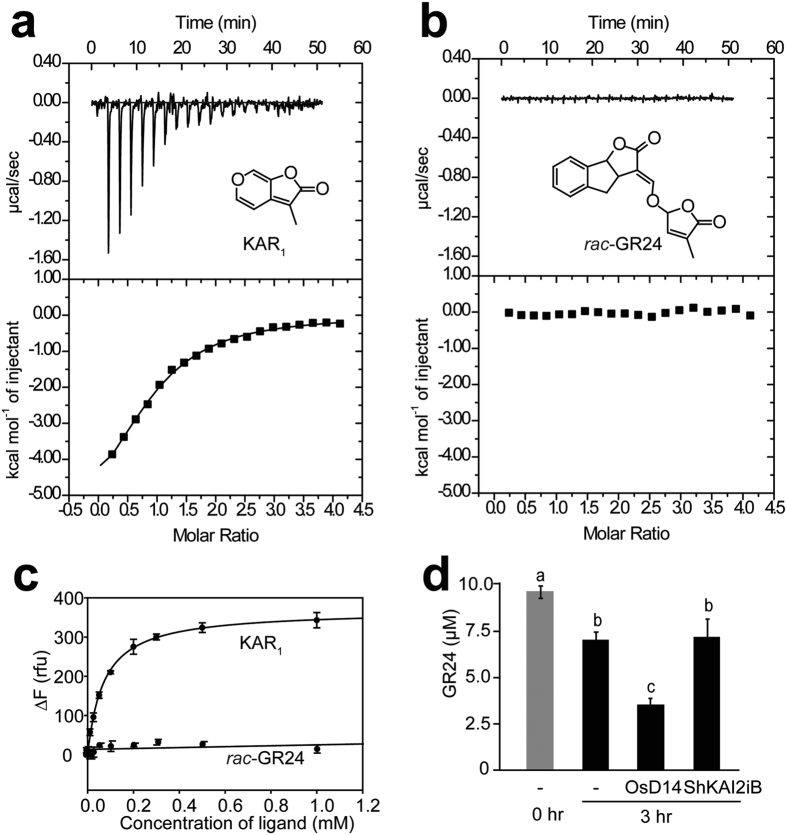

ITC (isothermal titration calorimetry) experiments along with intrinsic fluorescence assays were used to determine the binding properties of ShKAI2iB towards KAR1 (3-methyl-2H-furo [2,3-c] pyran-2-one, a member of the karrikin family) and rac-GR24 (synthetic SL analogue). The results of the ITC experiments involving ShKAI2iB and KAR1 showed a dissociation constant (KD) of 77.6 ± 3.4 μM, and the intrinsic fluorescence assays showed a KD of 70.0 ± 3.4 μM (Fig. 1a–c). However, no detectable heat change or fluorescence change were observed after adding rac-GR24 to ShKAI2iB. In addition, our hydrolysis assay with HPLC (Fig. 1d) indicated that ShKAI2iB was not capable of hydrolyzing rac-GR24, although it has been reported that KAI2 is able to bind both KAR1 and GR24 and exhibits hydrolytic activity toward GR2416. Our results indicated a novel binding specificity in which ShKAI2iB bound karrikin but not SL, in agreement with the reported results of cross-species complementation assays of ShKAI2i18.

Figure 1. Binding specificity of ShKAI2iB.

(a,b) Results of ITC experiments of ShKAI2iB titrated with KAR1 (a) and rac-GR24 (b). Binding of KAR1 to ShKAI2iB exhibited a KD value of 77.6 ± 3.4 μM, along with ΔH (enthalpy change) of −6.48 ± 0.4 kcal mol–1, ΔS (entropy change) of –3.99 cal mol–1 deg–1 and N (number of sites) of 0.91 ± 0.05 (Supplementary Figure S4 and Table S2). (c) Changes of fluorescence intensity by the addition of KAR1 and rac-GR24 to ShKAI2iB. Intrinsic fluorescence was recorded at excitation wavelength of 285 nm and emission wavelength of 333 nm. Fitting using SigmaPlot 13.0 indicated that KD value was 70.0 ± 3.4 μM (n = 3) for KAR1 binding to ShKAI2iB. (d) Enzymatic degradation assay of rac-GR24. The data means ± SE of three independent experiments. Statistical differences between the groups were calculated with ANOVA analysis followed by Tukey–Kramer test. Bars with different letters are significantly different with p < 0.01.

Overall structure of ShKAI2iB

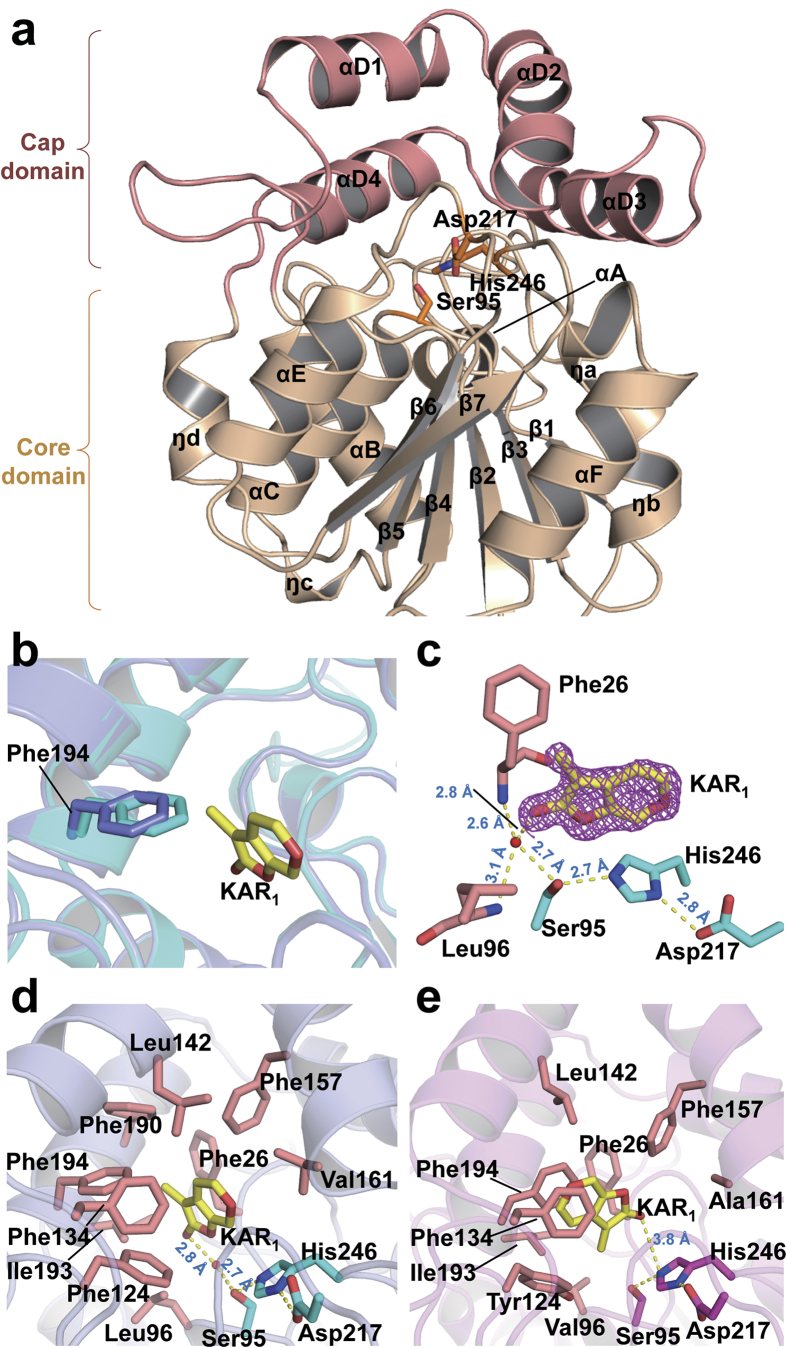

To determine why ShKAI2iB exhibited a different binding specificity from KAI2 and D14s, we solved crystal structures of apo ShKAI2iB at 2.0-Å resolution and ShKAI2iB-KAR1 complex at 1.2-Å resolution (Supplementary Figure S3 and Table S1). ShKAI2iB consisted of a core domain and a cap domain (Fig. 2a). The core domain, also known as α/β hydrolase domain26, was composed of seven strands (β1–β7), five helices (αA, αB, αC, αE and αF) and four 310 helices (ŋa, ŋb, ŋc and ŋd) as shown in Fig. 2a. The cap domain was composed of 4 tandem helices, which forms two antiparallel V shapes (αD1-αD2 and αD3-αD4) stabilized mainly by hydrophobic interactions between overlapping helices. Meanwhile, this cap domain was connected to the core domain by loops β5-αD1 and αD4-ŋd, and contacted by loops β2-ŋa, β3-ŋc and β7-αF through hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions. A cavity was formed between the two domains, in common with other KAI2/D14 proteins reported12,20,21,22,23,24,25, and catalytic triad (Ser95-His246-Asp217) lied at the bottom of the cavity.

Figure 2. Structures of ShKAI2iB and its KAR1 complex.

(a) Structure overview of ShKAI2iB in a ligand-free (apo) state. Cap domain and core domain are colored salmon and wheat, respectively. Catalytic triad residues are indicated as cyan sticks. (b) Structural alignment of apo- (cyan) and KAR1-bound ShKAI2iB (purple). Phe194 and KAR1 (yellow) are highlighted in stick model. (c) Hydrogen-bonding network between KAR1 and the catalytic residues of ShKAI2iB. KAR1 is shown by a yellow stick and contoured 2Fo-Fc map (Pink mesh) at level of 1.0σ. Catalytic triad residues are highlighted in cyan sticks and the residues for oxyanion hole are in salmon sticks. Red sphere represents water molecule. Hydrogen bonds and their lengths are represented using dashed lines and blue values (Å), respectively. (d,e) Binding modes of KAR1 in the cavity of ShKAI2iB (d) and KAI2 ((e) PDB ID 4JYM). Residues surrounding KAR1 (yellow) are highlighted in salmon sticks. Catalytic triad residues of ShKAI2iB are shown as cyan sticks and those of KAI2 are shown in magenta sticks. Red spheres stand for water molecules. Hydrogen bonds are represented by yellow dashes and lengths are shown with blue values (Å).

KAR1-binding mode of ShKAI2iB

Comparing crystal structures of apo and KAR1-bound ShKAI2iB, no significant structural changes were observed, except Phe194 in the cavity (Fig. 2b). Upon KAR1 binding, Phe194 moved 1 Å away from KAR1 binding site, creating a space to accommodate KAR1. Interestingly, Phe194 was also the only residue in the cavity that possessed conformational change for D-OH-bound OsD1423 and KAR1-bound KAI221. However, F194A mutation showed no significant change in the results of our ITC assays (Supplementary Figure S4 and Table S2), indicating that its phenyl group was not required to capture KAR1 although it could be moved to expand the KAR1-binding site.

In the complex structure of ShKAI2iB-KAR1, KAR1 was embedded completely in the cavity, with the oxygen-bearing edge facing down, and thus, the carbonyl group of KAR1 pointing toward the bottom of the cavity (Fig. 2c). Carbonyl oxygen of KAR1 in the ShKAI2iB-KAR1 structure was able to form hydrogen bond with the hydroxyl group of Ser95 through a water molecule. This water molecule also formed hydrogen bonds with main-chain amide nitrogen atoms of Phe26 and Leu96, which acts as an oxyanion hole in catalytic activity of α/β hydrolase. Moreover, methyl group of KAR1 (ShKAI2iB) was embedded in the hydrophobic side consisting of Phe26, Phe190, Ile193 and Phe194. Actually, S95A exhibited almost no heat change following the addition of KAR1 in the ITC experiment (Supplementary Figure S4), indicating that Ser95 is vital for KAR1 binding, likely by stabilizing a water molecule in the vicinity. In consistent with this observation, Ser95 has been reported to be essential for normal seedling karrikin responses of Arabidopsis KAI227.

On the other hand, the methyl group of KAR1 was embedded in the hydrophobic side consisting of Phe26, Leu142, Phe190, Ile193 and Phe194, and the pyran ring of KAR1 formed face-to-edge aromatic-dipole interactions and hydrophobic interactions with ShKAI2iB. The results of our ITC assays showed that L142A and F190L mutants exhibited a two-fold decrease in affinity for KAR1 with KD value of 196 ± 24 μM and 186 ± 43 μM, respectively (Supplementary Figure S4 and Table S2). In addition, a Val139 mutation in Leu, a residue that interacts with KAR1 in KAI2, showed two-fold higher affinity (KD value of 36 ± 7 μM), suggesting that Val139 might strengthen the hydrophobic interaction with KAR1. Consequently, KAR1 fit in the cavity of ShKAI2iB and was stabilized by both hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions.

Structural bases for KAR1 binding

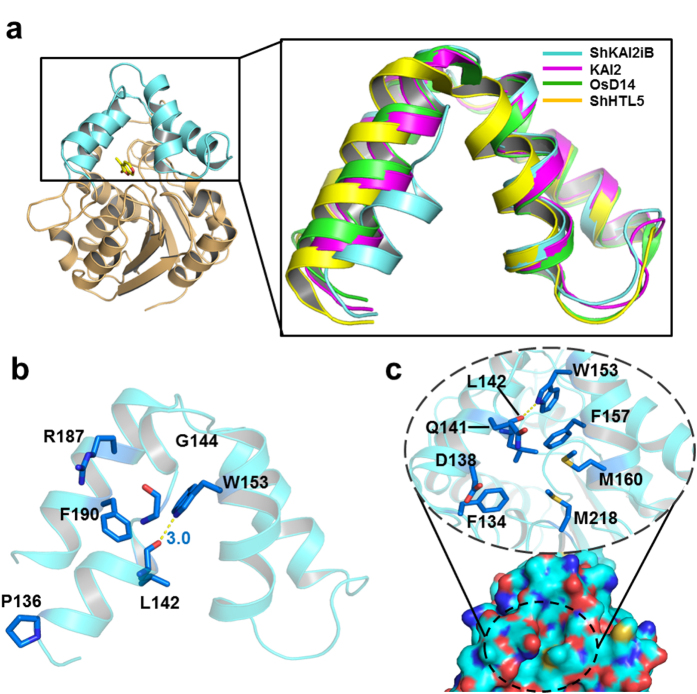

However, the KAR1-binding mode of ShKAI2iB was different from that of KAI2. In the KAI2-KAR1 structure (PDB ID 4JYM), KAR1 was upside down with the methyl group pointing toward the catalytic triad instead and was located at a slightly distal position from Ser95 (Fig. 2e)21. To investigate the structural basis for different binding mode of KAR1 in ShKAI2iB and KAI2, we compared the structure of ShKAI2iB with KAI2. Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between the two structures was 0.8 Å for 262 Cα atoms superimposed. In spite of the overall structural similarity as well as high sequence identity as mentioned above, there were some structural differences between ShKAI2iB and KAI2. Superposition of ShKAI2iB with other KAI2 and D14 showed that inward shift occurred on helix αD1 of ShKAI2iB, which subsequently narrowed the KAR1-binding pocket of ShKAI2iB (Fig. 3a). There are four major structural bases for this inward shift of helix αD1. In the structure of ShKAI2iB, Pro136 was located at the N-terminus of helix αD1, as opposed to Gln136 in the structure of KAI2, resulting in a sharper turn than that of KAI2, which forces helix αD1 to lean towards helix αD2 (Fig. 3b). Meanwhile, helix αD1 has the highly flexible amino acid Gly144 at its C-terminus, which disrupts helix αD1. In addition, two bulky residues in helix αD4, Arg187 and Phe190, extrude helix αD1 toward the cavity. Consequently, the helix αD1 approached to helix αD2, and a hydrogen bond forms between the side-chain amine of Trp153 and the main-chain carbonyl group of Leu142, which was exposed due to the disruption of helix formation by Gly144.

Figure 3. Structural basis for regulating the conformation of cap domain.

(a) Superposition of cap domain from ShKAI2iB in a ligand-free (apo) state (cyan) and KAI2 (apo, PDB ID 4JYP) (magenta), OsD14 (PDB ID 3WIO) (Green) and ShHTL5 (PDB ID 5CBK) (Yellow). (b) Regulatory residues in the cap domain of ShKAI2iB (ligand-free apo state). Blue sticks represent the residues involved in closed conformation of helix αD1. Hydrogen bond between Leu142 and Trp153 was indicated by yellow dashed line and bond length was shown in blue value (Å). (c) Surface representation (bottom) and residues around cavity entry of ShKAI2iB (top). Cyan, blue, red, and yellow surfaces represent carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur atoms, respectively. In the dashed circle, some residues of helix αD1 and αD2, which are supposed to be the access to KAR1 binding pocket, are emphasized in close-up view. The entrance is closed and inaccessible to solvent.

As a result of inward shift of helix αD1, the side chain of Leu142 will cause a steric clash with KAR1 if it takes the same orientation as that in the KAI2-KAR1 structure. Besides, the side-chain rotation of Phe194 is required to sandwich KAR1 between Phe194 and Phe134 in KAI2, whereas the same rotation cannot occur in ShKAI2iB because the rotated side-chain will sterically clash with the bulky Phe190 (Fig. 2d). Phe190 is a characteristic residue of ShKAI2iB that is substituted by a Gly residue in KAI2 (Gly190), and appears to take part in reinforcing the hydrophobic interaction of Leu142 and Phe194 with KAR1. These structural bases form a small cavity that precisely enough to encapsulate KAR1. As a result, compared with the cavity sizes of KAI2 (238 Å3), OsD14 (461 Å3) and ShHTL5 (713 Å3), the cavity of ShKAI2iB is the smallest: 155 Å3. This also explains why ShKAI2iB cannot accommodate SL, which is larger than karrikin.

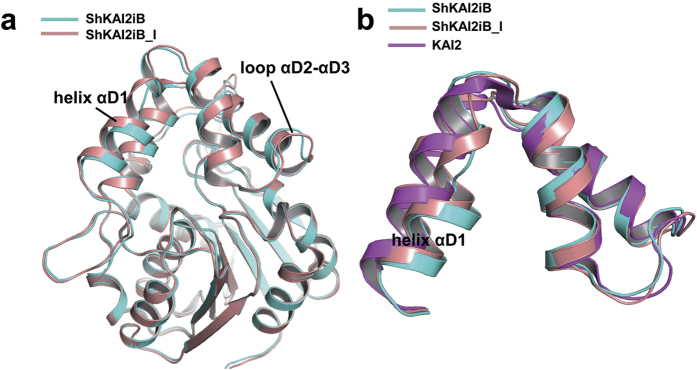

Conformational changes of cap domain

Another outcome derived from the inward shift of helix αD1 is the closing of the entrance to the ligand-binding cavity of ShKAI2iB (Fig. 3c). This shift of helix αD1 has been reinforced by hydrogen bond between Leu142 and Trp153. Moreover, the residues with bulky side chains, such as Phe134, Asp138, Gln141, Leu142, Phe157, Met160 and Met218, are located around the entrance and therefore clog the hydrophobic cavity. Unexpectedly, the complexed structure of ShKAI2iB with KAR1 also has a closed cavity, indicating that conformational changes of the cap domain are required to enable KAR1 to access the cavity. We suggest that helix αD1 might be the gate-keeper because different conformation of helix αD1 was observed in another ligand-free structure of ShKAI2iB [ShKAI2iB-I (intermediate)] during our attempt to acquire complex of ShKAI2iB with KAR1. Superposed structures of ShKAI2iB and ShKAI2iB-I showed that helix αD1 moved outwardly and caused conformational changes on the residues Leu142–Gly144 (Fig. 4). To compare the flexibility of helix αD1, we calculated the normalized B-factors by dividing every B-factors of helix αD1 by the average B-factors of overall structures. The normalized B-factors of helix αD1 are 1.3 for all three structures, suggesting that no significant difference in flexibility of helix αD1 between the three structures and helix αD1 is slightly more flexible than other part. Although the cavity of ShKAI2iB-I was also closed, the entrance was slightly open. These structures in the ligand-free state imply that helix αD1 adopts multiple conformations in solution. The addition of KAR1 might shift the equilibrium towards the ligand-binding conformation with a wider entry to the hydrophobic cavity. Therefore, we suggest that helix αD1 of ShKAI2iB might be allosterically involved in ligand binding and ShKAI2iB closed the gate again and locked KAR1 after capturing KAR1.

Figure 4. Structural alignment of two different conformations of ShKAI2iB.

(a) Superposition of two different conformations of ShKAI2iB in the ligand free (apo) state, ShKAI2iB (cyan) and ShKAI2iB-I (intermediate, salmon). Conformational changes between ShKAI2iB and ShKAI2iB-I are observed on helix αD1 and loop αD2-αD3 of cap domain. (b) Cap domain of ShKAI2iB in two states and KAI2 (apo, PDB ID 4JYP).

Discussion

A recent report indicates that KAI2 paralogues from S. hermonthica can be divided into three types: KAI2c clade that is most conserved with AtKAI2; KAI2d clade that is most diversely evolved and most likely to be involved in SL perception in S. hermonthica and KAI2i clade that is intermediate between KAI2c and KAI2d18. Among them, ShKAI2i is a KAI2 paralogue that responses to only karrikin for Arabidopsis seed germination through complementary assays. In the present study, we identified the intermediate KAI2-like protein with distinct characteristic from KAI2 and D14. According to our results and previous results of cross-species complementation assays of KAI218, ShKAI2iB was unable to bind and hydrolyze GR24 but capable of binding karrikin. Our structural study revealed that a few non-conserved amino acids led to the distinct ligand-binding profile of ShKAI2iB, supporting that evolution of KAI2 resulted in diverse functions of KAI2.

ShKAI2iB exhibited a different KAR1 binding mode from KAI2, by forming hydrogen bond between Ser95 and KAR1 through a water molecule, which means that Ser95 contributes to capturing karrikin but not hydrolysis of KAR1, because a covalent bond between Ser and carbonyl carbon of substrate is required for catalytic reaction. In fact, hydrolytic activity of KAI2 for KAR1 has not been reported. On the other hand, catalytic triad residues of D14/KAI2 proteins are not only important for enzymatic activity, but also necessary for interaction with other proteins or degradation-mediated feedback regulation12,23,28,29. For example, catalytic Ser residue is necessary for the interaction between DAD2 and PhMAX2A, a MAX2 orthologue from P. hybrida12. In the case of KAI2, both karrikin-induced and GR24-induced degradation of KAI2 has been observed in a Ser95-dependent manner29; however, it remains unclear whether catalytic reaction occurs in the karrikin perception of KAI2. Our results suggest that the catalytic Ser residue (Ser95) of ShKAI2iB functions to capture KAR1 at the active site, which might contribute to activating downstream signaling without catalytic reaction. In the crystal, the helix αD1 is near (about 3.5 Å) a helix (helix αF) from neighbor molecule; therefore, it is not excluded that the crystal contact affects the position of the helix αD1. However, ShKAI2iB should not take the same position of helix αD1 and bind KAR1 in the same mode as AtKAI2. If so, KAR1 is distal from Ser95, which conflicts with our ITC data that substitution of Ser95 to Ala abolishes binding. Although there are two other interactions from the main chain, Ser95 may be crucial for the overall network of KAR1 binding by stabilizing both the water molecule and the assumed catalytic residues His246 and Asp217.

In addition to the different recognition mode of catalytic triad Ser95, KAR1 exhibited other different binding characteristics in the catalytic cavity of ShKAI2iB and KAI2. In the latter case, KAR1 located at the outer entrance of KAI2’s cavity and possibly served as new interface for partner recognition21. In the structure of KAR1-bound ShKAI2iB, the cavity was closed and KAR1 was unable to be exposed to the solvent. Therefore, a distinct signal might be transferred by ShKAI2iB. Nonetheless, it was reported that ShKAI2i could be complementary to Arabidopsis KAI2 for germination induction by KAR1. Therefore, the recognition of KAR1 might be loose for signal transfer. On the other hand, this difference might imply a distinct function/response of ShKAI2iB in S. hermonthica. In fact, KAR1 failed to induce germination of S. hermonthica18,30, suggesting that KAR1 binding of ShKAI2iB might not be a signal of germination. Instead, it could be a sign that no hosts are near, which would keep the seeds dominant considering that karrikin is derived from smoke after forest fires. Interestingly, the transcripts of ShKAI2iB decreased during conditioning of Striga seeds (Supplementary Figure S5). This expression profile might suggest that ShKAI2iB functions to suppress of seed germination. There might also be other authentic endogenous ligands for ShKAI2iB as suggested for KAI2 previously27. Our structural evidences provide the ligand-binding specificity of ShKAI2iB toward KAR1, guiding the exploration of authentic endogenous ligands. On the other hand, according to the phylogenetic analysis (Supplementary Figure S1), there are other KAI2/D14 orthologues in S. hermonthica, some of which might be authentic SL receptor. Our study revealed that the helix αD1 was a key factor for ligand-binding specificity, providing additional information for discriminating SL receptor in S. hermonthica.

Methods

Overexpression and purification of recombinant proteins

The coding sequence cDNA of ShKAI2iB was amplified by PCR using total complementary DNA from the total RNA of 1-day conditioned Striga seeds. ShKAI2iB (1–270, C270S) was designed for crystallization and other assays. For expression in Escherichia coli, the PCR product was cloned into an expression vector pGEX-6P-3 (GE Healthcare) and subsequently transformed into E. coli strain Rosetta (DE3) (Novagen). IPTG-induced overexpression was performed for 20 h at 25 °C. For purification, cell pellets were lysed by sonication in buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.3 M NaCl, 1 mM DTT), and the soluble fraction separated by centrifugation was purified using Glutathione Sepharose 4B resin (GE Healthcare) and a Resource Q anion-exchange column (GE Healthcare). ShKAI2iB mutants were overexpressed and purified with the same procedure as wild-type protein. For crystallization, buffer exchange accompanied by concentration was performed using Vivaspin 20 (5,000 MWCO PES) (Sartorius). Purified ShKAI2iB was dialyzed against buffer B (20 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl) for the ITC experiments and the intrinsic fluorescence assay.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Binding assays of ShKAI2iB and KAR1 were performed using a MicroCal iTC200 isothermal titration calorimeter (GE Healthcare). Prior to the ITC experiments, concentrated ShKAI2iB was dialyzed against a buffer consisting of 20 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 8.0, and 50 mM NaCl to remove dithiothreitol and then adjusted to a final concentration of 150 μM. The sample cell was filled with ShKAI2iB solution (204 μl). Two microliters of 3 mM KAR1 or 3 mM rac-GR24 (equimolar mixture of two enantiomers: GR245DS and GR24ent-5DS) was injected into the prepared protein solution by 20 consecutive 2.0 μl aliquots at 150 s intervals at 10 °C. The first injection volume was 0.4 μl, and the observed thermal peak was excluded from the data analyses. Duplicate experiments were performed independently. A negative control was made by titrating 3 mM KAR1 into a buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl) in the same manner. Data fitting was performed using Origin software in the “one set of sites” mode. The dissociation constant (KD) values were calculated from duplicate thermograms (mean ± S.D.).

Intrinsic fluorescence assay

KD values were also determined by using intrinsic fluorescence assays. Fluorescence measurements were conducted as previously described16 with minor modifications. One microliter of KAR1 or rac-GR24 dissolved in DMSO was added to 100 μl of 10 μM protein solution to reach a certain concentration. Flat-bottomed, black 96 well plates were used to read fluorescence intensity using a Tecan Infinite M1000 monochromator. Measurements were taken at room temperature under a 285 nm excitation wavelength, a 333 nm emission wavelength, 50 flashes, and a 400 Hz flash frequency with a gain of 70 and a 2 μs integration time. ΔF (rfu, relative fluorescence units) was calculated by subtracting the fluorescence of the DMSO control. SigmaPlot 13.0 was used to fit and determine KD values with a one-site saturation model.

Enzymatic degradation assay

The enzymatic degradation assay of rac-GR24 was performed in a total volume of 1 ml of PBS buffer containing 10 μM rac-GR24. Purified OsD1423 and ShKAI2iB were added at a final concentration of 6 μg ml−1 and incubated for 3 h at 37 °C. Then 100 mg of NaCl and 100 μl of 0.1 M HCl were added to each reaction solution, and the reaction solutions were extracted with 400 μl of ethyl acetate three times. The ethyl acetate layers were combined and dried in vacuo and dissolved in 50 μl of methanol. For each layer, 10 μl was applied to the HPLC analyses. The reverse-phase chromatographic separation was performed on a Jasco HPLC system that was equipped with an HPLC pump of model PU 2080 (Jasco) and a photodiode array detector MD1510 (Jasco). The system was controlled by the ChromNAV (Ver. 1.18.07) software program (Jasco). The analytical column was a CAPCELL CORE C18 (Φ 4.6 × 100 mm, Shiseido). The analytes were eluted under gradient conditions using methanol ramped linearly to 90% methanol at 9 min and held for 4.5 min before resetting to the original conditions. The contents of rac-GR24 was calculated by the peak area at the retention time 6.2 min with the regression equation obtained from the calibration curve produced using a dilution series of rac-GR24 solution. Statistical analysis was performed by using the JMP11 software (SAS Institute Inc.). Statistical differences between the groups were calculated with ANOVA analysis followed by Tukey–Kramer test.

Crystallization, data collection, structure determination and refinement

Crystals were obtained using 7.4 mg ml−1 of ShKAI2iB protein with reservoir solution consisting of 100 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and 3 M sodium formate with sitting-drop vapor diffusion method at 4 °C. 3–4 weeks were necessary for the crystals to grow. Crystal of ShKAI2iB was picked up and soaked with the reservoir solution containing 25% (v/v) ethylene glycol as cryoprotectant before mounting. A diffraction data set was collected in a nitrogen cryostream of 95 K using an in-house Rigaku R-AXIS VII imaging-plate detector (Rigaku, Japan). The diffraction data were indexed, integrated and scaled using the XDS program31. The crystal belonged to space group P6122 possessing unit-cell parameters a = b = 75.9, c = 181.5 Å. Mathews coefficient was estimated to be 2.53 Å3 Da−1 and solvent content was 51.3%32, suggesting that there was one molecule in asymmetric unit. Molecular replacement was carried out using MOLREP33 of CCP4 program suite and the crystal structure of OsD14 (PDB ID 3VXK) as a template. BUCCANEER34 was applied for automatic model building. Refinement was performed using REFMAC535 and WINCOOT36 to a final Rwork of 18.0% and Rfree of 22.5%. PyMOL viewer (Version 1.5.0.4 Schrödinger, LLC) was used to depict all the structures and CASTp server37 was used to calculate volume of protein cavities using probe radius of 2.0 Å. During attempt of crystallization of ShKAI2iB with 2.5 mM KAR1, crystal structure of ShKAI2iB-I was solved using structure of ShKAI2iB as template model and final model was refined to Rwork of 20.7% and Rfree of 26.6%. No electron density of KAR1 has been observed. Complexed structure of ShKAI2iB with KAR1 was solved with soaking in addition to co-crystallization. Since the binding affinity of KAR1 to ShKAI2iB was slightly weak, we tried the crystallization of ShKAI2iB with the KAR1 concentration of 10 mM. Acquired crystal was soaked with 30 mM KAR1 for 5 hours and used for diffraction data collection. The collected data were indexed, integrated and scaled with HKL-200038. Crystal structure of KAR1-bound ShKAI2iB was solved by molecular replacement with the model of ShKAI2iB and finally refined to resolution of 1.2 Å with Rwork of 14.1% and Rfree of 15.5%. B-factors for each structure were calculated with Baverage39, and the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between the two structures was calculated using a Dali server40. Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Supplementary Table S1.

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree

CLUSTAL W41 was used for multiple sequence alignment with default parameters, and the result was displayed by ESPript 3.042. Aligned sequences included ShKAI2iB, KAI2 (A. thaliana KAI2, NCBI GI: 15235567), OsD14 (O. sativa D14, NCBI GI: 115451411), AtD14 (A. thaliana D14, NCBI GI: 75337534) and DAD2 (P. hybrida D14, NCBI GI: 404434487). Blastp searches were performed using the amino acid sequence of ShKAI2iB as a query against O. sativa and A. thaliana genus using non-redundant GenBank databases. Results were filtered using cut-off E value of 1e−8. EST sequences and genome sequences of S. hermonthica were investigated in the S. hermonthica EST Database (http://striga.psc.riken.jp/est2uni/) and Parasitic Plant Genome Project (http://ppgp.huck.psu.edu/). Sequences were further filtered and screened for truncation and duplication. Phylogenetic tree was created using MEGA version 643 with UPGMA method.

Striga germination

Seeds of S. hermontica harvested in Sudan were kindly provided by Prof. A.E. Babiker (Sudan University of Science and Technology) and imported with the permission from the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. The Striga germination assay was performed as described previously44. Striga hermontica seeds were surface sterilized and pre-incubated (conditioned) on glass paper disks placed on distilled water-satured filter paper at 30 °C. Then seeds were treated with 0.1 μM of GR24. After further incubation at 30 °C for 3 days, GR24-treated seeds were microscopically evaluated for germination.

Relative expression levels of the ShKAI2iB gene

Total RNA was extracted from conditioned seeds before GR24-treatment, purified with the Total RNA Extraction Mini Kit (RBC Bioscience), and converted to cDNA with the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Takara Bio) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Quantitative PCR was performed with SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara Bio) and the Thermal Cycler Dice Real Time System TP800 (Takara Bio). The transcript levels of ShKAI2iB were normalized against those of ShUBQ145, using primers specific for ShKAI2iB (5′-TAGGGTCGGTGGAAGGTCAGTC-3′ and 5′-CAGCACTGGGATGGCAACCT-3′), and ShUBQ1 (5′-CATCCAGAAAGAGTCGACTTTG-3′ and 5′-CATAACATTTGCGGCAAATCA-3′). Student’s t-test was used to determine the significance of differences relative to the transcript level in Striga seeds conditioned for 1 day.

Additional Information

Accession code: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession code 5DNW, 5DNV and 5DNU for ShKAI2iB, ShKAI2iB-I and KAR1-bound ShKAI2iB, respectively.

How to cite this article: Xu, Y. et al. Structural basis of unique ligand specificity of KAI2-like protein from parasitic weed Striga hermonthica. Sci. Rep. 6, 31386; doi: 10.1038/srep31386 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The synchrotron-radiation experiments were performed on beamlines AR-NW12A at Photon Factory with the approval of the High Energy Accelerator Research Organization (Proposal No. 2015R-25). This work was supported by the Platform for Drug Discovery, Informatics, and Structural Life Science from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (MEXT) (M.T.), and the Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST) Program of Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) (T.A.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions M.T. designed the research. Y.X. performed the biochemical experiments and collected X-ray diffraction data with T.M. H.N. performed the HPLC experiments, and H.N. and Y.I. performed the germination assay. Y.X., T.M. and A.N. analyzed the data. Y.X., T.M., T.A. and M.T. wrote the paper. M.T. edited the manuscript.

References

- Cook C. E., Whichard L. P., Turner B., Wall M. E. & Egley G. H. Germination of witchweed (Striga lutea Lour.): isolation and properties of a potent stimulant. Science 154, 1189–1190 (1966). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berner D. K., Kling J. G. & Singh B. B. Striga research and control – a perspective from Africa. Plant Disease 79, 652–660 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama K., Matsuzaki K. & Hayashi H. Plant sesquiterpenes induce hyphal branching in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Nature 435, 824–827 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Roldan V. et al. Strigolactone inhibition of shoot branching. Nature 455, 189–194 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umehara M. et al. Inhibition of shoot branching by new terpenoid plant hormones. Nature 455, 195–200 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flematti G. R., Ghisalberti E. L., Dixon K. W. & Trengove R. D. A compound from smoke that promotes seed germination. Science 305, 977 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flematti G. R., Ghisalberti E. L., Dixon K. W. & Trengove R. D. Identification of alkyl substituted 2H-Furo[2,3-c] pyran-2-ones as germination stimulants present in smoke. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57, 9475–9480 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D. C., Flematti G. R., Ghisalberti E. L., Dixon K. W. & Smith S. M. Regulation of seed germination and seedling growth by chemical signals from burning vegetation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 63, 107–130 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwanenburg B., Mwakaboko A. S., Reizelman A., Anilkumar G. & Sethumadhavan. D. Structure and function of natural and synthetic signalling molecules in parasitic weed germination. Pest Manag. Sci. 65, 478–491 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirnberg P., van De Sande K. & Leyser H. M. O. MAX1 and MAX2 control shoot lateral branching in Arabidopsis. Development 129, 1131–1141 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa S. et al. Suppression of tiller bud activity in tillering dwarf mutants of rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 46, 79–86 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamiaux C. et al. DAD2 is an α/β hydrolase likely to be involved in the perception of the plant branching hormone, strigolactone. Curr. Biol. 22, 2032–2036 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L. et al. DWARF 53 acts as a repressor of strigolactone signalling in rice. Nature 504, 401–405 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F. et al. D14-SCF(D3)-dependent degradation of D53 regulates strigolactone signalling. Nature 504, 406–410 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Strigolactone/MAX2-induced degradation of brassinosteroid transcriptional effector BES1 regulates shoot branching. Dev. Cell 27, 681–688 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh S., Holbrook-Smith D., Stokes M. E., Tsuchiya Y. & McCourt P. Detection of parasitic plant suicide germination compounds using a high-throughput Arabidopsis HTL/KAI2 strigolactone perception system. Chem. Biol. 21, 988–998 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters M. T. et al. Specialisation within the DWARF14 protein family confers distinct responses to karrikins and strigolactones in Arabidopsis. Development 139, 1285–1295 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn C. E. et al. Convergent evolution of strigolactone perception enabled host detection in parasitic plants. Science 349, 540–543 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya Y. et al. Probing strigolactone receptors in Striga hermonthica with fluorescence. Science 349, 864−868 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bythell-Douglas R. et al. The structure of the karrikin-insensitive protein (KAI2) in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE 8, e54758 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Zheng Z., La Clair J. J., Chory J. & Noel J. P. Smoke-derived karrikin perception by the α/β-hydrolase KAI2 from Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 8284–8289 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagiyama M. et al. Structures of D14 and D14L in the strigolactone and karrikin signaling pathways. Genes Cells 18, 147–160 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura H. et al. Molecular mechanism of strigolactone perception by DWARF14. Nat. Commun. 4, 2613 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L. et al. Crystal structures of two phytohormone signal-transducing α/β hydrolases: karrikin-signaling KAI2 and strigolactone-signaling DWARF14. Cell Res. 23, 436–439 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh S. et al. Structure-function analysis identifies highly sensitive strigolactone receptors in Striga. Science 350, 203–207 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardini M. & Dijkstra B. W. α/β hydrolase fold enzymes: the family keeps growing. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 9, 732–737 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters M. T., Scaffidi A., Sun Y. K., Flematti G. R. & Smith S. M. The karrikin response system of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 79, 623–631 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florian C. et al. Strigolactone promotes degradation of DWARF14, an α/β hydrolase essential for strigolactone signaling in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 26, 1134–1150 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters M. T., Scaffidi A., Flematti G. R. & Smith S. M. Substrate-induced degradation of the α/β-fold hydrolase KARRIKIN INSENSITIVE2 requires a functional catalytic triad but is independent of MAX2. Mol. Plant 8, 814–817 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiwocha S. D. S. et al. Karrikins: a new family of plant growth regulators in smoke. Plant Sci. 177, 252–256 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. X. D. S. Acta Cryst. D. 66, 125–132 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews B. W. Solvent content of protein crystals. J. Mol. Biol. 33, 491–497 (1968). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagin A. & Teplyakov A. MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J. Appl. Cryst. 30, 1022–1025 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Cowtan K. Fitting molecular fragments into electron density. Acta Cryst. D. 64, 83–89 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov G. N. et al. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Cryst. D. 67, 355–367 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P. & Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Cryst. D. 60, 2126–2132 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dundas J. et al. CASTp: computed atas of surface topography of proteins with structural and topographical mapping of functionally annotated residues. Nucl. Acids Res. 34, 116–118 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z. & Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn M. D. et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Cryst. D. 67, 235–242 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L. & Rosenström P. Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucl. Acids Res. 38, 545–549 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G. & Gibson T. J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucl. Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert X. & Gouet P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucl. Acids Res. 42, 320–324 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A. & Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto Y. & Ueyama T. Production of (+)-5-deoxystrigol by Lotus japonicas root culture. Phytochem. 69, 212–217 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Aparicio M. et al. Application of qRT-PCR and RNA-Seq analysis for the identification of housekeeping genes useful for normalization of gene expression values during Striga hermonthica development. Mol. Biol. Rep. 40, 3395–3407 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.