Case Vignette

“We've been waiting for you to come on the oncology service,” the oncology fellow said, as the resident and nurse practitioner on service looked on. “We have a really challenging case.”

Our patient was a frail 77-year-old woman with unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma, saddle pulmonary embolus, protein calorie malnutrition, hepatitis C, and recurrent infections, all of which had resulted in a lengthy hospital stay. Her cancer had progressed despite two lines of chemotherapy. She wanted more treatment, but had been told she was too weak. In our first meeting, she told me that her goal was “to get strong enough for more chemotherapy.” She had interpreted the previous oncology attending's statement about her fitness for chemotherapy as a challenge, and thought, “If I can get stronger, I can get more.” Knowing and trusting my colleague, I imagine his statement was meant as a stepping stone toward a transition to hospice. Her family fiercely defended her desire for rehabilitation as well (“Don't take away her hope,” they had said), so she remained in a hospital-based limbo, too weak for physical therapy and without sufficient understanding of her prognosis to allow a seamless transition to hospice.

As a dual board–certified medical oncologist and palliative care physician, I respected her hopefulness and recognized the challenges that I faced as a result of the complex and nuanced conversations that had occurred before I became involved in her care. I also recognized her profound suffering and that of her family, both because of my conversations with them and because of the heaviness I felt in my heart when entering her room. I suspect that every oncologist knows a version of the above scenario, and knows that heaviness of heart, too.

As physicians, we are often most comfortable in the medical and fact-based realms. However, in my palliative care training, I was taught to listen to the so-called limbic music in a room to try to identify the causes of suffering. Often the solution in a difficult clinical encounter lies in addressing emotional and spiritual needs as well as physical ones. Our team aggressively managed the patient's pain and nausea and then explored her suffering. As a member of a three-generation ranching family, she had been physically active until her diagnosis, and felt betrayed by her body. In the hospital, without her daily dose of open sky, she felt trapped. She did not have a will and worried about who would run the ranch after she passed. Her sons had a contentious relationship and often disagreed about how to care for her. She was overwhelmed and, frankly, not ready to die. She suffered in many realms—physical, emotional, interpersonal, financial and existential—and her suffering affected her decision making.

By identifying and addressing the causes of her suffering in the context of our goals-of-care discussions, we helped her to understand that she was not going to regain the physical ability to run the ranch, but that she might be able to see it again, that we could begin to address some of her financial and relationship concerns, and that those things were possible without more chemotherapy. Before her death in the hospital, she had completed a medical power of attorney, had met with her sons and a family lawyer to make a will, and had the opportunity to grieve openly with her sons about her anticipated death. From an educational perspective, an oncology fellow, resident, and nurse practitioner learned to recognize and assess “total pain,” Dame Cicely Saunder's concept of suffering that encompasses physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains.1

This vignette illustrates how palliative oncology experts can influence patient care and education in meaningful ways, and also how palliative care training adds a different dimension to the core skills that all oncologists use.

Palliative Oncology

The practice of oncology consists of two major domains: disease management and supportive care.1a Management of cancer is highly complex, requiring an intricate understanding of cancer biology, an excellent knowledge of state-of-the-art treatment options with their specific risks and benefits, and the capacity to make personalized recommendations about such treatments, taking into account the comorbidities and preferences that are unique to each individual patient. At the same time, optimal patient care necessitates a growing list of supportive care skills, including comprehensive symptom assessment and treatments, counseling, communication (eg, prognostic disclosures, end-of-life discussions), care planning, and end-of-life care.2

A majority of oncologists believe that they should be actively involved in the delivery of supportive/palliative care.3,4 Oncologists routinely manage complex symptoms and provide emotional support for patients and their families throughout the disease trajectory.5 Multiple oncology and palliative care organizations are actively developing education programs that are aimed at enhancing the repertoire of palliative care skills among oncologists.3,6 Importantly, patients with a higher level of distress or care needs should be referred to specialist interprofessional palliative care teams. There is now a growing body of evidence and interest to support the routine integration of early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer.7,8 At the same time, many barriers to palliative care referral remain, such as the misconception that palliative care is only for patients at the end-of-life, the death-defying mentality in our society, and many oncologists' strong sense of responsibility to provide care throughout the disease trajectory and not give up, so to speak, on their patients.9

We envision that oncologists with an interest in symptom management and psychosocial aspects of care may choose to specialize in the rapidly growing field of palliative oncology. Jackson et al10,11 conducted a qualitative study of oncologists about their approaches to end-of-life care and identified two phenotypes: type I oncologists, who incorporated both the biomedical and psychosocial aspects of care in their work, and type II oncologists, who focused on biomedical issues. Type I oncologists were more prepared to discuss end-of-life issues and find satisfaction in providing end-of-life care and were less likely to burn out. Among type I oncologists, those who are particularly palliphilic, as one might say, may choose to dedicate their careers to improving the quality of life of patients and their families through excellence in patient care, education, and research in palliative oncology. In this article, we will discuss the training pathways, career opportunities, challenges, and opportunities for palliative oncologists. All authors are dually certified palliative oncologists.

Training of Palliative Oncologists

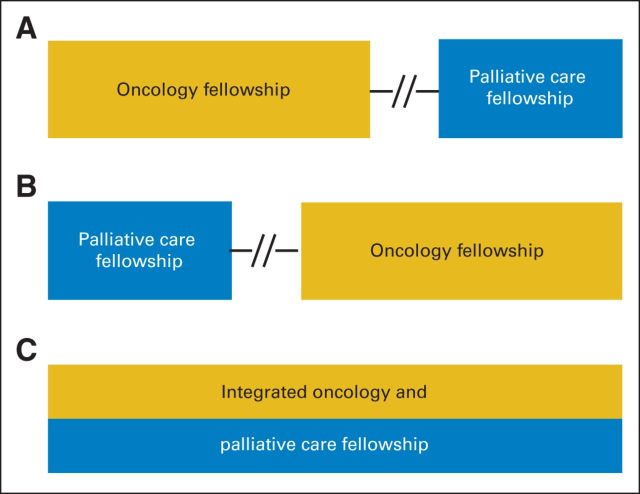

Many pioneers in palliative care trained initially as oncologists and over time developed a strong interest in palliative care. In 2006, palliative care became an accredited specialty in the United States. To be board certified in both oncology and palliative care, candidates who have met the requirements for certification in oncology must complete 1 year of palliative care training (Fig 1). This career path is open to all oncology specialties, including medical, radiation, surgical, and gynecologic oncology.

Fig 1.

Training pathways for supportive/palliative oncologists. Physicians interested in supportive/palliative oncology may (A) pursue an oncology fellowship followed by a palliative care fellowship, which may occur either immediately after or sometimes after years of oncology practice; (B) pursue these fellowships in a reverse order; or (C) enroll in a handful of integrated oncology/palliative care fellowships.

The Many Roles of Palliative Oncologists

Palliative oncologists as clinicians.

Instead of a new practice model in which palliative oncologists deliver both oncologic and palliative care simultaneously in one setting, a majority of palliative oncologists work and bill as either oncologists (eg, general or for specific tumor types) and/or palliative care specialists at academic centers or community settings. Some actively practice both specialties, prescribing chemotherapy as an oncologist one day and consulting with other oncologists as a palliative care specialist on another day. In this way, palliative oncologists promote collaborations within the existing system rather than compartmentalizing care. The exact nature of their position depends on the individual's interest and commitment to each specialty, job opportunities, and investment of institutional leadership. Regardless of the clinical setting, palliative oncologists uniquely combine the principles of oncology and palliative care to deliver high-quality cancer care.

In the oncology setting, palliative oncologists guide cancer management and offer high-quality supportive care. However, they may not be able to provide the same level of palliative care that they would in the specialist palliative care setting. A palliative oncologist may not refer as many patients to specialist palliative care because he or she may be able to address the patient's needs during routine clinical visits. That said, the palliative oncologist may recognize the need to refer patients with complex physical or emotional needs and thus provide access to expert care with important beneficial consequences for the patient and family caregivers. For patients weighing the risks and benefits of chemotherapy with noncurative intent, the palliative oncologist may be better suited to present all options, ranging from standard chemotherapy or supportive care without chemotherapy to participation in a clinical trial, in a balanced manner that allows individual patients to make informed decisions that are commensurate with their personal values and goals. As one patient told her palliative treating oncologist, “You made the decision to stop chemotherapy an easy choice for us.”

In the palliative care setting, a palliative oncologist practices specialist palliative care alongside an interdisciplinary team. This involves providing inpatient consultations or direct patient care on a designated palliative care unit or outpatient clinic. In all of these settings, the focus is on improving the quality of life of patients and their families. A palliative oncologist may be particularly adept at managing adverse effects of cancer treatment and in facilitating prognostic discussions and decision making regarding palliative cancer treatments, and may have added credibility when communicating with the patient's primary oncologist. Palliative oncologists may encourage a patient to consider a trial of cancer-directed therapy, recognizing its possible benefit to the patient after discussing his or her values, expectations, and hopes for the future.

Palliative oncologists as educators.

Because of their dual training, palliative oncologists are well positioned as educators for colleagues and trainees in both palliative care and oncology and can respond to the American Society of Clinical Oncology's call to enhance palliative care education of oncology trainees.3,12,13 Although most oncologists embrace palliative care as a core responsibility, the literature suggests that there is some room for improvement in areas such as pain control and breaking bad news.3,14 Palliative oncologists can teach key palliative care skills, serve as role models because of their expertise in communication, and advocate for appropriate referral to specialist palliative care.

Palliative oncologists can help their nononcology-trained colleagues and palliative care fellows appreciate the wide variation in prognosis, expected response to treatment among different types of cancer, treatment adverse effects, and the general principles of treatment decision making.

Palliative oncologists as researchers.

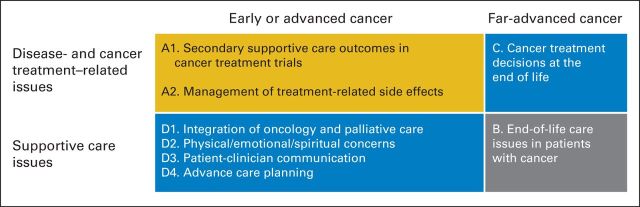

Discoveries are often made at the intersection of disciplines. The evidence base for palliative oncology is rapidly evolving. There are numerous opportunities on many under-researched topics, such as symptom management, psychosocial and spiritual care, treatment toxicities, communication, decision making, and health services research for patients throughout the continuum of care.15 Having a strong knowledge base in both specialties, palliative oncologists are uniquely positioned to conduct pioneering research at the palliative care–oncology interface (Fig 2). For instance, a recent systematic review on integration of oncology and palliative care revealed that palliative oncologists authored a majority of the articles.16 Palliative oncologists also have a leading role in many symptom-control clinical trials that target the oncology population in topic areas such as cancer-related fatigue and dyspnea.17 Moreover, their expertise allows important secondary outcomes to be incorporated into oncology clinical trials that traditionally focus on tumor response and survival. For instance, phase I oncologists recently collaborated with palliative oncologists to examine the antitumor effect and anticachetic effect of an interleukin-1α antibody.18 Palliative oncologists have also been actively investigating the decision-making process surrounding cancer treatments at the end of life.

Fig 2.

Research opportunities in supportive/palliative oncology. Supportive/palliative oncologists, because of their specialized training, are well equipped to participate in multiple areas of research, including (A) cancer treatment trials (eg, on quality-of-life assessments, supportive care end points, adverse effects), (B) palliative care issues at the end of life (ie, 6 months or less of life expectancy), (C) treatment decisions at the end of life, and (D) promotion of cancer care delivery models that introduce palliative care principles early in the disease trajectory. The last two topic areas are of particular interest to supportive/palliative oncology researchers because of their combined expertise and patient access.

Palliative oncologists as ambassadors.

Integration of oncology and palliative care requires an in-depth understanding of each discipline as well as how providers can work together most effectively. The historical stereotypes of oncologists who treat too long and palliative care physicians who give up too early are no longer helpful in the era of personalized cancer treatments and comprehensive supportive care. Palliative oncologists have an important role in destigmatizing palliative care, promoting collaboration between the two teams, and advocating for resources to support better integration. Palliative oncologists can help oncologists and palliative care specialists to engage in a dialogue that is respectful and productive, while recognizing the different perspectives. These so-called bilingual diplomats understand the language and culture of both worlds and the strengths and weaknesses of each discipline. For example, palliative oncologists can help their palliative care colleagues appreciate why an oncologist would choose to treat a patient with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer in the first-line setting despite a performance status of 4. At the same time, palliative oncologists may help reduce oncologists' fear that palliative care specialists will not respect their decisions to prescribe cancer-directed therapy with palliative intent. Indeed, the presence of a palliative oncologist within a cancer center may be a marker of integration.

Challenges

As an emerging field, the training pathways are less well defined for palliative oncology than for other oncology subspecialties (eg, hematologic oncology). In a survey of US cancer centers, only 38% of National Cancer Institute (NCI) –designated cancer centers and 17% of non–NCI-designated cancer centers offered palliative care fellowship training programs.19 However, interested individuals may receive their palliative care and oncology fellowship training at two different institutions. In countries in which palliative care is not an accredited discipline, the process of obtaining formalized training in palliative oncology is particularly challenging. Nevertheless, many oncologists who have an interest in palliative care are able to acquire the core skills through workshops, rotations, and training programs and focus their research in this area.

Because palliative oncology is not yet an established career path, newly trained fellows often need to work closely with potential employers to craft a position that would best meet the other's needs. Intellectually, it may be challenging for palliative oncologists to keep up to date with both fields equally, and many eventually focus in only one area of practice. Financially, palliative oncologists may be at a disadvantage compared with other oncologists because the practice of palliative care is associated with limited downstream revenue. Despite having spent additional time training and maintaining multiple certifications, a palliative oncologist might be compensated at a lower rate because palliative care is reimbursed at a lower rate than oncology. Thus, palliative oncologists may be more likely to work at major academic centers that offer an equitable salaried structure. Increasingly, institutions recognize the value of palliative care in improving quality of care, and the indirect effect on health care savings through the reduction of nonreimbursable costs such as chemotherapy use in the last 14 days of life. Psychologically, palliative oncologists may run a risk of increased burnout because of the work load and emotional toll, particularly if they are asked to see the more distressed patients and do not receive adequate support and resources. Furthermore, although patient-reported outcomes are increasingly recognized as valid and valuable end points in cancer care, they are still often seen as secondary to tumor response and survival. By choosing to focus their career on so-called secondary end points, palliative oncologists may find their work discounted by some of their colleagues.

Future Directions

In this era of personalized medicine, palliative oncology has emerged as a field that uniquely blends the art and science of patient care. Collaborating closely with oncologists and palliative care teams, palliative oncologists can lead the efforts that fundamentally address the human aspects of care, so to speak, through exemplary patient care, education, and research.

Going forward, program directors from different oncology subspecialties and palliative care need to collaborate to increase training opportunities for palliative oncology by developing structured dual-training programs. Taking this concept further, a 3-year palliative medical oncology (or palliative hematology) fellowship may be a reasonable alternative to the medical oncology/hematology fellowship for some individuals. Currently, a vast majority of medical oncology trainees in the United States spend 3 years in combined oncology/hematology fellowships. Depending on their practice, a proportion of these oncologists may not engage in the practice of both specialties. In contrast, oncologists who are dually trained in palliative care and oncology will be able to apply both their oncology and palliative care skills in their clinical practice. This would require a paradigm shift in oncology training and a strong commitment from program directors. Having a palliative oncologist in a leadership position of a training program may catalyze this process.

Cancer center leadership can also support this new subspecialty by hiring palliative oncologists, endorsing initiatives that are aimed at integrating oncology and palliative care, and providing appropriate reimbursement. Encouragingly, many institutions have now expressed interest in dually training individuals. For instance, the leaders of palliative care programs at many NCI-designated comprehensive cancer centers in the United States are palliative oncologists.

Funding bodies also have a critical role to play in fostering the next generation of palliative oncology subspecialists by providing training grants. They may also dedicate research funding to the wide array of palliative oncology topics that are aimed at improving the quality of life and quality of care of patients with cancer. For example, the American Cancer Society has a request for application related to “Pilot and Exploratory Projects in Palliative Care of Cancer Patients and Their Families.” NCI and the American Society of Clinical Oncology have also supported groundbreaking research in palliative oncology.7,20

Admittedly, palliative oncology will not be a calling for everyone. However, palliative oncology merges the oncology specialists' intricate understanding of a growing array of anticancer therapies with the specialty-level palliative care providers' knowledge of symptom management, psychosocial care, communication, and prognostication, with the goal of facilitating comprehensive cancer care through cross-pollination. For individuals who envision closer collaborations between oncology and palliative care for the purposes of enhancing the quality of care and making exciting discoveries that might help to improve patients' quality of life, palliative oncology is a rewarding subspecialty with boundless opportunities for patient care, education, and research.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Disclosures provided by the authors are available with this article at www.jco.org.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Palliative Oncologists: Specialists in the Science and Art of Patient Care

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

David Hui

No relationship to disclose

Esmé Finlay

Stock or Other Ownership: Merck

Mary K. Buss

No relationship to disclose

Eric E. Prommer

No relationship to disclose

Eduardo Bruera

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Saunders C. A personal therapeutic journey. BMJ. 1996;313:1599–1601. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7072.1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1a.Bruera E, Hui D. Integrating supportive and palliative care in the trajectory of cancer: Establishing goals and models of care. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4013–4017. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.5618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoong J, Park ER, Greer JA, et al. Early palliative care in advanced lung cancer: A qualitative study. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2013;173:283–290. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferris FD, Bruera E, Cherny N, et al. Palliative cancer care a decade later: Accomplishments, the need, next steps—From the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3052–3058. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cherny NI, Catane R. European Society of Medical Oncology Taskforce on Palliative and Supportive Care: Attitudes of medical oncologists toward palliative care for patients with advanced and incurable cancer: Report on a survey by the European Society of Medical Oncology Taskforce on Palliative and Supportive Care. Cancer. 2003;98:2502–2510. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care: Creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1173–1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1721–1730. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schenker Y, Crowley-Matoka M, Dohan D, et al. Oncologist factors that influence referrals to subspecialty palliative care clinics. J Oncol Pract. 2013;10:e37–e44. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson VA, Mack J, Matsuyama R, et al. A qualitative study of oncologists' approaches to end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:893–906. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Gunten CF. Oncologists and end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:813. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.9888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Von Roenn JH, Voltz R, Serrie A. Barriers and approaches to the successful integration of palliative care and oncology practice. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(suppl 1):S11–S16. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Partridge AH, Seah DS, King T, et al. Developing a service model that integrates palliative care throughout cancer care: The time is now. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3330–3336. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buss MK, Lessen DS, Sullivan AM, et al. Hematology/oncology fellows' training in palliative care: Results of a national survey. Cancer. 2011;117:4304–4311. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hui D, Parsons HA, Damani S, et al. Quantity, design, and scope of the palliative oncology literature. Oncologist. 2011;16:694–703. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hui D, Kim YJ, Park JC, et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: A systematic review. Oncologist. 2015;20:77–83. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruera E, Hui D. Palliative care research: Lessons learned by our team over the last 25 years. Palliat Med. doi: 10.1177/0269216313477177. [epub ahead of print on February 26, 2013] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong DS, Hui D, Bruera E, et al. MABp1, a first-in-class true human antibody targeting interleukin-1α in refractory cancers: An open-label, phase 1 dose-escalation and expansion study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:656–666. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70155-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M, et al. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA. 2010;303:1054–1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruera E, Hui D, Dalal S, et al. Parenteral hydration in patients with advanced cancer: A multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:111–118. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.6518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.