Abstract

Background:

Alleviating pain is of utmost importance when treating patients with endodontic pain.

Aim:

To compare and evaluate the efficacy of two modes of delivery of pretreatment Piroxicam (Dolonex®, Pfizer) for the management of postendodontic pain.

Materials and Methods:

Sixty-six patients with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis were randomly divided into three groups of 22 subjects Group I - control group, no pharmacological intervention, Group II - patients received pretreatment oral Piroxicam (40 mg), Group III - patients received pretreatment intraligamentary injections totaling 0.4 mL of Piroxicam. Single visit endodontic therapy was performed by a single endodontist. Visual analogue scale was used to record pain before treatment and 4, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h postoperatively. Mann–Whitney U-test and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to analyze the data.

Results:

The patients in Groups II and III perceived less postendodontic pain as compared to Group I (P < 0.05), at all the time intervals. At 12, 24, and 48 h, pain experience in patients of Group III was significantly less.

Conclusions:

Intraligamentary mode of delivery of Piroxicam was more efficacious.

Keywords: Intraligamentary injection, Piroxicam, postendodontic pain, preemptive analgesia

INTRODUCTION

Pre-, intra-, and post-treatment endodontic pain is dreaded, remembered and shared by patients.[1] Pain following root canal treatment occurs with a highly variable reported prevalence ranging from 82.9% as described by Glassman et al. to 10.6% stated by Oliet.[2] Pain is usually more intense in the first 48 h and progressively reduces with the passage of time until usually disappearing after 7–10 days.[3,4] Pain may not indicate endodontic failure, relief of this pain is often more important to the patient than the success of the treatment.[5]

Postendodontic pain usually results from instrumentation and/or obturation.[6] During instrumentation, extrusion of microorganisms or debris is common and has been reported to elevate the inflammatory response.[7] These procedures cause the release of inflammatory mediators including prostaglandins.[4] Persistent pain after endodontic therapy may lead to patient dissatisfaction.[8] Pain management usually involves occlusal reduction, administration of systemic analgesics, anti-inflammatory drugs, or antibiotics.[9] Inhibition of the inflammatory process involves the inhibition of the release of the inflammatory mediators.[10] Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID's) and glucocorticoids control pain by similar mechanisms. NSAID's act primarily through the inhibition of cyclo-oxygenase enzymes (COX enzymes 1 and 2), and in turn, COX-2 inhibition prevents prostaglandin formation ultimately preventing inflammation and sensitization of peripheral nocireceptors.[11] Preemptive analgesia has been defined as an anti-nociceptive treatment that prevents altered processing of afferent input amplifying postoperative pain.[12] Since endodontic patients come to the office already in pain, a more clinically relevant term to use would be pretreatment analgesia.[12] This technique may decrease the establishment of central sensitization, a mechanism whereby spinal neurons increase their responsiveness to peripheral nociceptive input.

NSAID's are one of the most frequently advised analgesic. Their popularity is attributed to their over-the-counter availability, efficacy in relieving pain and fever, and low side effect profile at therapeutic doses.[13] Piroxicam, a nonselective NSAID may be useful in pain control. Half-life of which is 50 h. Injection of this anti-inflammatory agent directly into the site of inflammation is effective.[10]

Very few studies have evaluated the efficacy of various modes of delivery of Piroxicam in the management of postendodontic. Hence, this study aimed at establishing the effectiveness of pretreatment Piroxicam in management of postendodontic pain and compare the efficacy of two modes of delivery of pretreatment Piroxicam; oral and intraligamentary for management of pain after single visit endodontics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sixty-six patients were selected from the outpatient clinic of the Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, M S Ramaiah Dental College, Bengaluru. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institution. A sample size of twenty two subjects in each group was advocated. Subjects were randomly divided into three groups by allocation concealment method.[14] Group I – control group, Group II – oral Piroxicam group, and Group III – intraligamentary Piroxicam group. Inclusion criteria was healthy persons, 18–65 years of age reporting with pain in first or second premolar of either jaw. Teeth diagnosed as symptomatic irreversible pulpitis with no recent history of any antibiotic or analgesic taken were included in the study. Teeth that could be treated endodontically in one visit was also a criteria. Patients with known hypersensitivity to Piroxicam, pregnancy or lactation, history of asthma or allergy to anti-inflammatory drugs, and history of stomach and intestinal disorders were excluded.

An informed consent was taken from the patient before starting the procedure after which a visual analog scale (VAS) standard tool for rating pain was explained and given to them and they were asked to self-assess their pain preoperatively. In Group I, patients were anesthetized with standard injections (block and/or infiltration) with 1.8 mL of 2% lidocaine containing 1:80,000 epinephrine. After eliciting the established onset of local anesthesia, root canal treatment of teeth was carried following a standard protocol. Patients in Group II were given two dispersible tablets of Piroxicam 20 mg (DolonexDT®, Pfizer, India) each ½ h before the procedure and were treated similar to Group I patients. For patients in Group III (intraligamentary Piroxicam) Piroxicam cartridges were prepared prior to the study, by removing the rubber plungers from the standard anesthetic cartridges, which were emptied, washed with distilled water and then autoclaved. The method of preparation of the Piroxicam cartridges was identical to the method as set out in Elsharrawy's article on supplemental intraligamentary injection of fentanyl and mepivacaine.[15] Empty sterile anesthetic cartridges of lidocane were filled with Piroxicam (20 mg/mL) solution from the commercially available vials (Dolonex®, Pfizer, India). These cartridges were loaded into the Midwest Comfort Control™ Syringe (Dentsply International, York, PA, USA), and the flow rate was adjusted for the intraligamentary injection (0.07 mL/s) as per manufacturers' instructions. Patients tooth was anesthetized with standard injections (block and/or infiltration) with 1.8 mL of 2% lidocaine containing 1:80,000 epinephrine. After eliciting the established onset of local anesthesia, patients received supplemental intraligamentary injection of 0.4 mL of 20 mg/mL Piroxicam as an active drug. 0.2 mL on either side, i.e. mesiobuccal and distobuccal line-angles of the tooth. Root canal treatment of teeth was carried out under the same protocol as in Group I.

After completion of the endodontic treatment, the patients were asked to self-assess the severity of pain experienced by them at 4, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h following the completion of treatment and mark the appropriate score according to the VAS scale in the evaluation form. All patients were given a rescue pill (acetaminophen 750 mg) in case of pain, and they were asked to mark their score in the evaluation form before consuming the pill.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed with the use of the nonparametric tests such as the Mann–Whitney U-test and the Kruksal–Wallis test by using SPSS software (version15, SPSS Inc, Chicago). P < 0.05 were used to indicate significant differences.

RESULTS

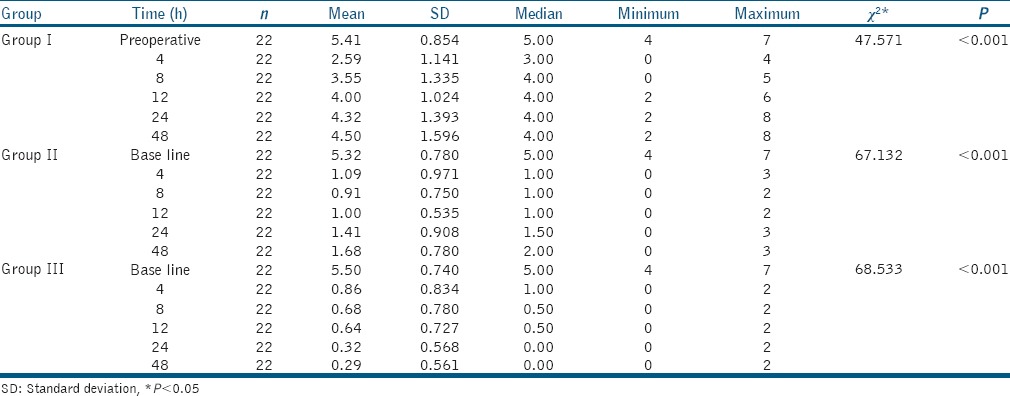

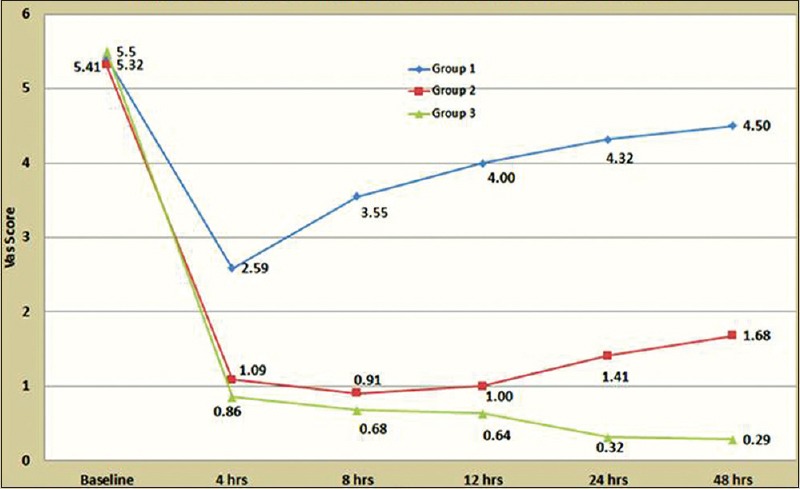

Table 1, Figure 1 depicts the evaluation of the pain scores within each of the Groups. The patients in Group I (control group) reported significantly less pain 4 h postoperatively, oral piroxicam given to the patients in Group II seemed to alleviate the pain up to 8 h postoperatively, and in Group III, the intraligamentary Piroxicam demonstrated an unmatched efficacy by mitigating the postendodontic pain up to 48 h when compared to their preoperative VAS scores, and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Intragroup comparison of the postendodontic pain scores

Figure 1.

Comparison of mean visual analog scale scores at different time intervals

DISCUSSION

While pain during therapy is usually controlled by local anesthesia, postoperative pain control is often and may contribute to the development of hyperalgesia leading to greater pain later.[16,17] Pain control in endodontic patients should be efficacious with minimum side-effects. Posttreatment pain in endodontics has been reported to occur in 25–40% of all endodontic patients.[18] Most of the investigators have found that there is a strong relationship between preoperative and postoperative pain.[19,20,21]

Patients in the control group experienced reduction in pain 4 h postoperatively as compared to their preoperative pain. This could be due to the 'Floor Effect' commonly attributed to the endodontic treatment rendered. However, at other postoperative intervals, i.e., at 8, 12, 24, and 48 h, it was observed that patients experienced a gradual increase in their pain. We observed that patients experience pain up to 48 h, i.e., the period of observation of the study; after single visit endodontic therapy. This observation is in accordance with various studies that state; patients with pretreatment pain frequently experience posttreatment.[19,20,21]

Irritation of periradicular tissues during root canal therapy causes an acute inflammatory reaction and results in pain and/or swelling.[21] Many endogenous chemical mediators, particularly prostaglandins, have been associated with inflammation and its related pain. In this study, NSAIDs were selected for several reasons. First, they inhibit the synthesis of prostaglandins. Prostaglandin suppression is particularly important because it lowers the pain threshold (i.e., produces allodynia) and sensitizes nociceptors to other pain mediators.[22] Second, although prostaglandins are only one of many pronociceptive inflammatory mediators, it is important to realize that their tissue levels are associated with patient reports of pain,[23] suggesting that NSAIDs may be key drugs for pain abatement. Third, NSAIDs are widely available without prescription, and some studies suggest that NSAIDs are effective in managing endodontic pain.[24]

This study aims at evaluating a NSAID for the management of postendodontic pain, in which 40 mg of oral Piroxicam was given to the patient half an hour before initiating the treatment as prescribed by various authors as the permissible dose for managing acute pain. About 0.4 mL of intraligamentary Piroxicam was given in accordance with Adnan Atebai's study.[10] Results showed that the variables such as age, sex, tooth type were not statistically different in all the three groups.

Both oral and intraligamentary Piroxicam did minimize the postendodontic pain experienced by all the patients in Group II and III at all the time intervals, i.e., 4, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h postoperatively as compared to patients in the Group I (control group) (P < 0.05).

The difference in amount of alleviation of pain achieved in patients by oral and intraligamentary Piroxicam; Group II and III at 4 and 8 h postoperatively was not very pronounced (P < 0.448), but at intervals 12, 24, and 48 h postoperatively, intraligamentary Piroxicam proved to be efficacious in abating the pain in patients belonging to Group III as compared to that of patients in Group II where the pain initially seemed to dwindle but during later postoperative hours, the pain escalated gradually and this difference between Group II and III was statistically significant (P < 0.001). Piroxicam's half-life of 50 h could favorably overcome the intense pain up to 48 h following the treatment.[25]

Oral Piroxicam alleviated the patient's postendodontic pain only up to 8 h postoperatively [Table 1]. The reason for this can be extrapolated to the bioavailability of Piroxicam which is 100% when given as an intraligamentary injection at the target site in comparison to that of the oral Piroxicam as it has to undergo hepatic by-pass before reaching the target site. Thus, the drug available at the target site is less in oral group; hence, supporting the results.[25] Results of the present study are in accordance with that of other studies where the authors have used NSAID's or steroids to be deposited directly in the periapical area either by intraligamentary route, giving a periapical injection or a supra-periosteal injection to gain effective control over postendodontic pain.

Various complications are associated with an intraligamentary injection; swelling and discoloration of soft tissue at the injection site and prolonged ischemia of interdental papilla followed by sloughing and exposure of crestal bone. Most common causes of postinjection discomforts are either rapid injection or injection of excessive volume of solution into the site.[10] The patients in the present study did not report with any such discomfort or complications as the abovementioned causes of discomfort were negated by the use of Comfort Control Syringe™.

Further research is required involving a more extensive follow-up for critically evaluating the effectiveness of Piroxicam beyond 48 h. Though there is enough literature on the use of VAS, there are still few concerns regarding the same. The values of the VAS scale are according to the pain threshold level of individual patient, which may vary to a considerable extent. Further clinical studies comparing the effectiveness of Piroxicam with other group of pharmacological agents can be carried out.

This trial further reiterated the fact that patients reporting with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis more often than not experience posttreatment pain of varying intensities. In such patients, a preemptive analgesic would go a long way to alleviate their pain.

CONCLUSIONS

However, within the limitations of the study, it can be concluded that Piroxicam was effective in allaying the postendodontic pain experienced by the patient. It was further observed that among oral and intraligamentary mode of delivery of Piroxicam, the latter proved to be more efficacious in abating postendodontic pain for a period up to 48 h.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pak JG, White SN. Pain prevalence and severity before, during, and after root canal treatment: A systematic review. J Endod. 2011;37:429–38. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arias A, de la Macorra JC, Hidalgo JJ, Azabal M. Predictive models of pain following root canal treatment: A prospective clinical study. Int Endod J. 2013;46:784–93. doi: 10.1111/iej.12059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehrvarzfar P, Pochapski MT. Effect of supraperiosteal injection of dexamethasone on post-operative pain. Aust Endod J. 2008;34:25–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2007.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrmann EH, Messer HH, Clark RM. Flare-ups in endodontics and their relationship to various medicaments. Aust Endod J. 2007;33:119–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2007.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jariwala SP, Goel BR. Pain in endodontics: Causes, prevention and management. Endodontology. 2001;13:63–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nazaroglou I, Kafas P, Dabarakis N. Post-operative pain in dentistry: A review. Surg J. 2008;3:96–103. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham CJ, Mullaney TP. Pain control in endodontics. Dent Clin North Am. 1992;36:393–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walton R, Fouad A. Endodontic interappointment flare-ups: A prospective study of incidence and related factors. J Endod. 1992;18:172–7. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)81413-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glassman G, Krasner P, Morse DR, Rankow H, Lang J, Furst ML. A prospective randomized double-blind trial on efficacy of dexamethasone for endodontic interappointment pain in teeth with asymptomatic inflamed pulps. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:96–100. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(89)90310-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atbaei A, Mortazavi N. Prophylactic intraligamentary injection of piroxicam (feldene) for the management of post-endodontic pain in molar teeth with irreversible pulpitis. Aust Endod J. 2012;38:31–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2010.00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holstein A, Hargreaves KM, Niederman R. Evaluation of NSAID's for treating post endodontic pain – A systematic review. Endod Topics. 2002;3:3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kissin I. Preemptive analgesia. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:1138–43. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200010000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Attar S, Bowles WR, Baisden MK, Hodges JS, McClanahan SB. Evaluation of pretreatment analgesia and endodontic treatment for postoperative endodontic pain. J Endod. 2008;34:652–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Allocation concealment in randomised trials: Defending against deciphering. Lancet. 2002;359:614–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07750-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elsharrawy EA, Elbaghdady YM. A double-blind comparison of a supplemental interligamentary injection of fentanyl and mepivacaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine for irreversible pulpitis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:203–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gordon SM, Dionne RA, Brahim J, Jabir F, Dubner R. Blockade of peripheral neuronal barrage reduces postoperative pain. Pain. 1997;70:209–15. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03315-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon SM, Brahim JS, Rowan J, Kent A, Dionne RA. Peripheral prostanoid levels and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug analgesia: Replicate clinical trials in a tissue injury model. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;72:175–83. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.126501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bramy E, Reader A, Gallatin E, Nist R, Beck M, Weaver J. Pain reduction in symptomatic, necrotic teeth using an intraosseous injection of depo-medrol. J Endod. 1999;25:289. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200011000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torabinejad M, Cymerman JJ, Frankson M, Lemon RR, Maggio JD, Schilder H. Effectiveness of various medications on postoperative pain following complete instrumentation. J Endod. 1994;20:345–54. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)80098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrison JW, Baumgartner JC, Svec TA. Incidence of pain associated with clinical factors during and after root canal therapy. Part 2. Postobturation pain. J Endod. 1983;9:434–8. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(83)80259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Genet JM, Wesselink PR, Thoden van Velzen SK. The incidence of preoperative and postoperative pain in endodontic therapy. Int Endod J. 1986;19:221–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1986.tb00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferreira SH, Nakamura M, de Abreu Castro MS. The hyperalgesic effects of prostacyclin and prostaglandin E2. Prostaglandins. 1978;16:31–7. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(78)90199-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNicholas S, Torabinejad M, Blankenship J, Bakland L. The concentration of prostaglandin E2 in human periradicular lesions. J Endod. 1991;17:97–100. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)81737-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doroschak AM, Bowles WR, Hargreaves KM. Evaluation of the combination of flurbiprofen and tramadol for management of endodontic pain. J Endod. 1999;25:660–3. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(99)80350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL. Goodman & Gilman's the Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Publishing Division; 2006. [Google Scholar]