Abstract

Aim:

The aim of this study is to evaluate the effect of alcohol and nonalcohol containing mouth rinses on the color stability of a nanofilled resin composite restorative material.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 120 samples of a nanofilled resin composite material (Tetric N-Ceram, Ivoclar Vivadent AG, FL-9494 Schaan/Liechtenstein) were prepared and immersed in distilled water for 24 h. Baseline color values were recorded using Color Spectrophotometer 3600d (Konica Minolta, Japan). Samples were then randomly distributed into six groups: Group I - distilled water (control group), Group II - Listerine, Group III - Eludril, Group IV - Phosflur, Group V - Amflor, and Group VI - Rexidin. The postimmersion color values of the samples were then recorded, respectively.

Results:

Significant reduction in the mean color value (before and after immersion) was observed in nonalcohol containing mouth rinses (P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

All mouthrinses tested in the present in-vitro study caused a color shift in the nanofilled resin composite restorative material, but the color shift was dependent on the material and the mouthrinse used. Group VI (Rexidin) showed maximum color change.

Keywords: Alcohol and nonalcohol containing mouth rinses, color stability, nanocomposite

INTRODUCTION

A quest for an ideal and esthetically acceptable restorative material is probably as old as dentistry itself and patients consciousness of self-aesthetics has been enabled by the development of composite resins.[1,2]

Mouthrinses being the simple vehicle of such agents serve as an adjunct to the mechanical means for prevention and control of caries, periodontal diseases, for the cessation of plaque, moreover for diminishing oral malodor. Many varieties such as alcohol and nonalcohol-based mouthrinses are used popularly as a mean for the maintenance of oral hygiene by the patients on a regular basis.[3,4]

Discoloration of the resin composites has a multifactorial etiology, many internal and external features may cause an alteration in color of these materials, out of which the proprietary mouthrinses are one of the causative factor for discoloration. However, studies have revealed that color stability of restorative materials can be reduced by both alcohol-containing and alcohol-free mouth rinses. Based on such thinking and the literature documentation done by various studies, the present in-vitro study was carried out to assess the effect of alcohol and nonalcohol-based mouthrinses on the color stability of a nanofilled resin composite restorative material.[4,5,6,7,8,9]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

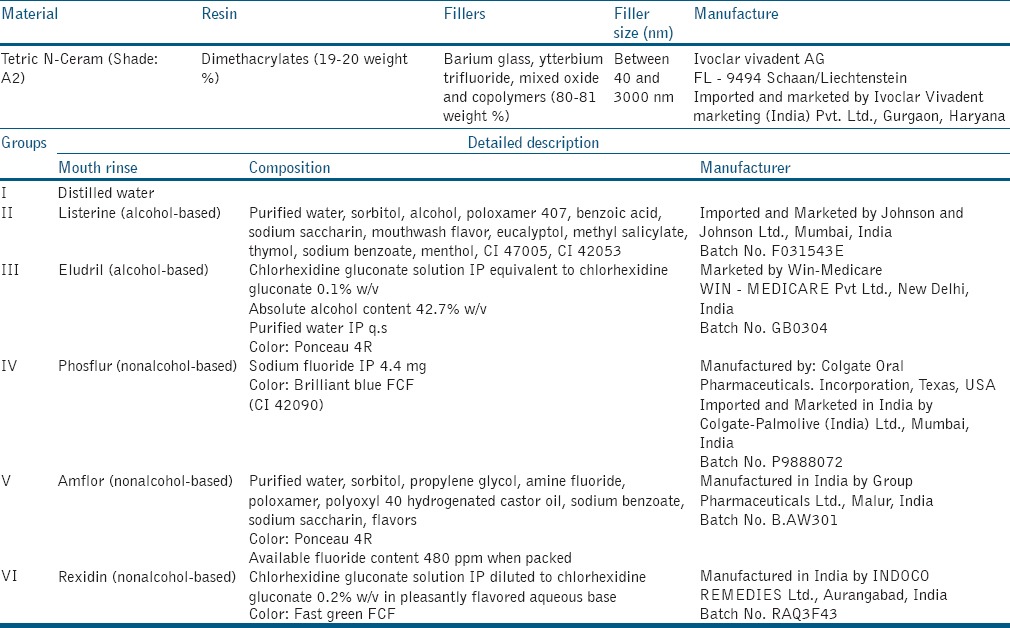

The description of the commercially available mouthrinses and the nanofilled resin composite are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Product profile of the nanofilled resin composite restorative material and composition of the mouth rinses used in the present in-vitro study

Specimen preparation

A total of 120 samples of nanofilled resin composite restorative material of size 10 mm in diameter and 2 mm in height were prepared using a customized teflon mold. The mold was placed on a glass slab (Neelkanth Health Care (P) Ltd., Jodhpur, India) and filled with composite using composite filling instrument (Rotex, Germany). It was then covered with a clean matrix strip (Samit Matrix Strips, India), another glass slab was placed on top and gently pressed for 30 seconds to extrude the excess material for achieving a smooth surface. Each specimen was then cured for 40 seconds from the top and another 40 seconds from the bottom using LED light cure unit (Guilin Woodpecker Medical Instrument Co., Ltd, China) (having not <450 mW/cm2).

pH evaluation

The pH of distilled water and the five commercial mouth rinses was evaluated using a digital pH meter (Systronics. Naroda, Ahmedabad, India). The values are:

The pH for Group I – Control group (distilled water) was found to be 7.14, for Group II Listerine: 4.14, for Group III Eludril: 4.5, for Group IV Phosflur: 4.39, for Group V Amflor: 4.7, and for Group VI Rexidin: 5.6.

Color stability

All the prepared samples were immersed in 20 ml of distilled water followed by incubation at 37°C for 24 hours. After 24 hours, baseline color value of each sample was recorded using Color Spectrophotometer 3600d (Konica Minolta, Japan).

Samples were then randomly divided into six groups as following: Group I – Control group (distilled water), Group II – Listerine (alcohol-based), Group III – Eludril (alcohol-based, alcohol-chlorhexidine containing), Group IV – Phosflur (non alcohol-based, sodium fluoride containing), Group V – Amflor (non alcohol-based, amine fluoride containing), and Group VI – Rexidin (non alcohol-based, chlorhexidine-containing). Each group comprised 20 sample each (n = 20).

The samples of each group were then immersed in 20 ml of their respective mouth rinse followed by incubation at 37°C for 24 hours. The after immersion color value of each sample was evaluated using the same color spectrophotometer. The data were collected, tabulated, and subjected to statistical analysis.

Statistical tests

The intragroup (pre- and post-immersion values) comparison of the mean color value of the samples was done by paired t-test. Color change between the groups was compared by performing one-way nonparametric ANOVA, i.e., Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA test. Multiple comparisons were made by Wilcoxon Rank Sum test. The effect of mouthrinses on the color stability of the nanofilled resin composite restorative material was compared by post hoc Wilcoxon Rank Sum test (Mann–Whitney test). The data were analyzed using STATA version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, Texas, USA) and the level of significance was set at P = 0.05.

RESULTS

Significant change in the color stability was shown by the non alcohol-based mouthrinses.

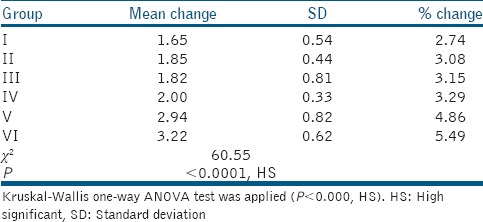

Mean change in the color, i.e., (before and after immersion) for distilled water (Group I) was 2.74%, for Listerine (Group II) 3.08%, for Eludril (Group III) 3.15%, Phosflur (Group IV) 3.29%, Amflor (Group V) 4.86%, and Rexidin (Group IV) 5.49% [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of mean color change (before and after immersion) in six groups

The ΔE value of the samples, when immersed in Distilled water, was found to be 1.65.

For alcohol-based mouthrinses

Samples when immersed in Listerine, ΔE was 1.85

The ΔE was found to be 1.82 when samples were immersed in Eludril. These values are less than the clinically tolerable value for color changes in dental materials (assumed to be ΔE*ab ≤ 3.3) [Table 2].

For non alcohol-based mouthrinses

The ΔE value of the samples when immersed in Phosflur (Group IV) was 2.00

For Amflor (Group V), ΔE was found to be 2.92

Whereas the maximum color change was shown by Rexidin (Group VI) which was ΔE = 3.22 [Table 2].

By applying the post hoc comparison by Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test (Mann–Whitney test) when non alcohol-based mouthrinses were compared with the alcohol-based mouthrinses, there was highly significant difference (P < 0.001). This indicated that the nonalcohol-based mouthrinses affected the color stability of the nanofilled resin composite restorative material.

When Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA test was applied to compare the mean values of color stability (before and after immersion) of six different groups, the difference was highly significant, i.e., (P < 0.0001) and the Kruskal–Wallis statistics was 60.55 [Table 2]. When Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA test was applied to compare the mean values of color stability (before and after immersion) of three different groups (control group, alcohol-based group, and nonalcohol-based group), the difference was highly significant, i.e., (P < 0.0001) and the Kruskal–Wallis statistics was 45.29.

DISCUSSION

Composite resins were introduced in the field of aesthetic, restorative dentistry, in view of reducing the shortcomings of the acrylic resins. Till date, the most substantial contribution of Nanotechnology to dentistry has been the restoration of tooth structure with the newly developed nanocomposites. The unique nature of the filler particles of nanocomposite provides it with increased hardness, abrasion resistance, fracture resistance, polishability, reduced polymerization shrinkage (1.4–1.6% by volume), and shrinkage stress.[9]

Discoloration of tooth-colored, resin-based materials may be affected by numerous intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic factors involve the staining of the resin material itself, such as variation of the resin matrix and changes in the interface of matrix and fillers. The resin matrix has been described as critical to color stability, and staining may be linked to a high resin content and water absorption.[10]

Discoloration can be estimated with different instruments and techniques. In evaluating chromatic differences, the Commission Internationale de l'Eclairage (CIE L*, a*, b*) system was chosen for this study. According to this system, L* signifies the lightness of the sample, a* defines green-red axis (−a = green; +a = red) and b* describes blue-yellow axis (−b = blue; +b = yellow). It is also possible to calculate the total color change (ΔE*ab), which cogitates the changes of L*, a*, and b*. Various studies have different inceptions of color difference values which are appreciable to the human eye. However, the clinically tolerable value for color changes in dental materials is presumed to be ΔE*ab ≤ 3.3.[10,11]

In this study, samples of Group I (control group) when immersed in distilled water, showed color change, i.e. ΔE as 1.65. This change in color of the tested nanofilled resin composite restorative material was not perceptible. These results are in accordance with Lee et al. (2000), Gürdal et al. (2002), and Diab et al.[3,13,14]

Samples of Group II, when immersed in Listerine mouthrinse (alcohol-containing), showed color change ΔE as 1.85. Although Listerine has low pH (4.14) with high alcohol content, in this study the color stability of the tested composite was not affected. These results are in accordance with Diab et al. (2007) and ElEmbaby Ael-S et al. (2014). Accordance with Festuccia et al. (2012) who reported that significant color change was found by Listerine.

Samples of Group III when immersed in Eludril mouthrinse (alcohol-chlorhexidine containing), the change in color, i.e. ΔE as 1.82. Although the alcohol content of Eludril is high with low pH (4.5), the change in color was not perceptible.[3,4] These results are in accordance with Diab et al (2007), Celik et al (2008).

When samples of Group IV were immersed in Phosflur mouthrinse (sodium fluoride containing), color change ΔE was 2.00. These results are in accordance with Lee et al. (2000). These results are in disagreement with Diab et al. (2007), who reported that sodium fluoride containing mouthrinse showed the highest change in color of the tested resin composite restorative materials. This may be due to the percentage of sodium fluoride in Flucal (0.2%) which is higher than that of Phosflur (0.044%). Hence, no significant color change was found in samples when immersed in Phosflur in the present in-vitro study.[12,13]

Samples of Group V, when immersed in Amflor mouthrinse (amine-fluoride containing), showed change in color ΔE as 2.94, which is less than the clinically acceptable value (assumed to be ΔE*ab ≤ 3.3) for color change in dental materials. Hence, the color change shown by Amflor was not visually perceptible. These results are in agreement with Lee et al. (2000), Gürdal et al. (2002), and Diab et al. (2007).

When samples of Group VI were immersed in Rexidin mouthrinse (chlorhexidine-containing), the color change ΔE was 3.22, which is very close to the clinically standard value for color variations in dental materials (assumed to be ΔE*ab ≤ 3.3).[13,14]

Among the three non alcohol-based mouthrinses (Phosflur, Amflor, Rexidin) used in the present study, Rexidin showed maximum color change ΔE as 3.22 in the nanofilled resin composite restorative material because chlorhexidine-containing mouthrinses having 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate, affect the color stability of resin composites. These results are in accordance with Celik et al. (2008),[4] Bagis et al. (2011)[19], and Poggio et al.[15,16,17,18,19]

Intergroup comparison revealed that non alcohol-based mouthrinses (Group IV – Phosflur, Group V – Amflor, and Group VI – Rexidin) when were compared with the alcohol-based mouthrinses (Group II – Listerine and Group III – Eludril) there was highly significant difference (P < 0.001). This indicated that the nonalcohol-based mouthrinses affected the color stability of the nanofilled resin composite restorative material.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of the present experimental study and the parameters used, it can be concluded that:

Mouthrinses with low pH are more detrimental to the hardness rather than to color stability

The present study appears to support the hypothesis that chlorhexidine-containing mouthrinse having 0.2% of chlorhexidine gluconate cause perceptible color change of the nanofilled resin composite restorative material

All mouthrinses tested in this in-vitro study caused a color shift in the tested nanofilled resin composite restorative material, but the color shift was dependent on the material and the mouthrinse used.

Clinical recommendations

Patients having resin composite restorations in the esthetic zone should avoid using mouthrinses which contain high concentration of chlorhexidine gluconate

In addition, there is variety of commercially available nanocomposites in the market; it would be pertinent to include other types of composite resins in future studies

Any new mouthrinse, introduced into the market should be tested for its effect on the properties of tooth-colored restorative materials.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rawls HR, Josephine FE. Restorative resins. In: Anusavice KJ, editor. Phillip's Science of Dental Materials. 11th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 2010. pp. 399–437. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Theodore MR, Harald OH, Edward JS. Sturdevants's Art and Science of Operative Dentistry. 4th ed. Mosby; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diab M, Zaazou MH, Mubarak EH, Olaa MI. Effect of five commercial mouthrinses on the microhardness and color stability of two resin composite restorative materials. Aust J Basic Appl Sci. 2007;1:667–74. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Celik C, Yuzugullu B, Erkut S, Yamanel K. Effects of mouth rinses on color stability of resin composites. Eur J Dent. 2008;2:247–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.George R. Nanocomposites – A review. J Dent Oral Biol. 2011;2:38–40. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swift EJ. Nanocomposites. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2005;17:3–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandki R, Kala M, Kumar KN, Brigit B, Banthia P, Banthia R. 'Nanodentistry': Exploring the beauty of miniature. J Clin Exp Dent. 2012;4:e119–24. doi: 10.4317/jced.50720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferracane JL. Current trends in dental composites. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1995;6:302–18. doi: 10.1177/10454411950060040301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terry DA. Direct applications of a nanocomposite resin system: Part 1 – The evolution of contemporary composite materials. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2004;16:417–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ElEmbaby Ael-S. The effects of mouth rinses on the color stability of resin-based restorative materials. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2014;26:264–71. doi: 10.1111/jerd.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dietschi D, Campanile G, Holz J, Meyer JM. Comparison of the color stability of ten new-generation composites: An in vitro study. Dent Mater. 1994;10:353–62. doi: 10.1016/0109-5641(94)90059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Festuccia MS, Garcia Lda F, Cruvinel DR, Pires-De-Souza Fde C. Color stability, surface roughness and microhardness of composites submitted to mouthrinsing action. J Appl Oral Sci. 2012;20:200–5. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572012000200013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SY, Huang HM, Lin CY, Shih YH. Leached components from dental composites in oral simulating fluids and the resultant composite strengths. J Oral Rehabil. 1998;25:575–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.1998.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gürdal P, Akdeniz BG, Hakan Sen B. The effects of mouthrinses on microhardness and colour stability of aesthetic restorative materials. J Oral Rehabil. 2002;29:895–901. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2002.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khokhar ZA, Razzoog ME, Yaman P. Color stability of restorative resins. Quintessence Int. 1991;22:733–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uchida H, Vaidyanathan J, Viswanadhan T, Vaidyanathan TK. Color stability of dental composites as a function of shade. J Prosthet Dent. 1998;79:372–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(98)70147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poggio P, Dagna A, Lombardini M, Chiesa M, Bianchi S. Staining of dental composite resins with chlorhexidine mouthwashes. Ann di Stomat. 2009;LVIII(3):62–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehmann KM, Devigus A, Igiel C, Weyhrauch M, Schmidtmann I, Wentaschek S, et al. Are dental color measuring devices CIE compliant? Eur J Esthet Dent. 2012;7:324–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bagis B, Baltacioglu E, Ozcan M, Ustaomer S. Evaluation of chlorhexidine gluconate mouthrinse-induced staining using a digital colorimeter: An in vivo study. Quint Int. 2011;42:213–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]