Abstract

Aim:

This in vitro study evaluated and compared the marginal adaptation of three newer root canal sealers to root dentin.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty freshly extracted human single-rooted teeth with completely formed apices were taken. Teeth were decoronated, and root canals were instrumented. The specimens were randomly divided into three groups (n = 10) based upon the sealer used. Group 1 - teeth were obturated with epoxy resin sealer (MM-Seal). Group 2 - teeth were obturated with mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) based sealer (MTA Fillapex), Group 3 - teeth were obturated with bioceramic sealer (EndoSequence BC sealer). Later samples were vertically sectioned using hard tissue microtome and marginal adaptation of sealers to root dentin was evaluated under coronal and apical halves using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and marginal gap values were recorded.

Results:

The data were statistically analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple post hoc test. The highest marginal gap was seen in Group 2 (apical-16680.00 nm, coronal-10796 nm) and the lowest marginal gap was observed in Group 1 (apical-599.42 nm, coronal-522.72 nm). Coronal halves showed superior adaptation compared to apical halves in all the groups under SEM.

Conclusion:

Within the limitations of this study epoxy resin-based MM-Seal showed good marginal adaptation than other materials tested.

Keywords: EndoSequence BC sealer, marginal adaptation, MM-Seal, mineral trioxide aggregate Fillapex

INTRODUCTION

The primary objective of root canal obturation is to obtain a fluid hermetic seal. Gutta–percha with sealer is the most often used solid core material in endodontic obturations.[1] However, Gutta–percha does not bond to root dentin. Moreover, over a period microleakage occurs at the sealer-core or sealer-dentin interface resulting in failure of root canal treatment. According to Strindberg and Allen long-term endodontic failure is due to lack of complete canal seal.[2] To overcome these drawbacks new systems have been introduced to enhance the sealing ability.

C points and EndoSequence BC sealer is the recently introduced obturation system, which is composed of zirconium oxide, calcium silicate, calcium phosphate monobasic, and calcium hydroxide. This sealer is a premixed, injectable, hydrophilic product that utilizes moisture within the dentinal tubules to initiate and complete setting reaction. Moreover, according to the manufacturer C points on contact with moisture in instrumented root canal space expand laterally and does not shrink on setting resulting in superior marginal adaptation.[3]

The other recently introduced sealer is mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) Fillapex, which is MTA-based sealer. It is a two paste system consisting of MTA, salicylate resins, bismuth oxide, silica nanoparticles, and pigments. This sealer has good sealing ability, bactericidal effect, high biocompatibility, and low solubility.[4]

MM-Seal (Micro Mega) is an epoxy resin-based root canal sealer packaged in a dual syringe. It is available in two pastes-base paste consists of epoxy oligomer resin, ethylene glycol salicylate, calcium phosphate, bismuth subcarbonate and zirconium oxide and catalyst paste consists of polyamine benzoate, triethanolamine, calcium phosphate, bismuth subcarbonate, and calcium oxide. It has better chemical and physical properties, biocompatible, and provides excellent sealing as claimed by manufacturer.

The aim of present study is to compare and evaluate the quality of adaptation of recently introduced EndoSequnce BC sealer, MTA Fillapex (MTA-based sealer) and MM-Seal (epoxy resin-based sealer) to root canal dentin using scanning electron microscope.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Thirty extracted mature human mandibular premolars were used for this study. The teeth were cleaned of debris and soft tissue remnants and were stored in saline solution. All the samples were sectioned at the cementoenamel junction with a low-speed diamond disc. Access opening was done, and the length of the canal was measured with No. 10 K-file. When the tip of the file was visible at the apex, 1 mm short of the file length was considered to be the working length. Instrumentation was done in crown down fashion using protaper rotary file system up to F3. In between the files, the canals were irrigated with 5.25% sodium hypochlorite solution, 17% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and finally rinsed with distilled water and dried with sterile paper points.

The samples were randomly divided into three groups based on the sealer used:

Group 1 - epoxy resin-based sealer (MM-Seal Micro Mega)

Group 2 – MTA-based sealer (MTA Fillapex Angelus, Londrina, Brazil)

Group 3 - Bioceramic Sealer (EndoSequence BC brasseler, USA).

Group 1 (MM-Seal)

According to the manufacturers' instructions, an appropriate amount of base and catalyst (2:1 wt ratio) are squeezed onto a mixing plate. They were mixed with the spatula for 15–20 s until the mix is creamy and homogeneous. After thorough drying of canals, MM-Seal was applied, and canals were obturated with corresponding protaper Gutta–percha points.

Group 2 (mineral trioxide aggregate Fillapex)

The sealer is mixed using a self-mixing tip attached to a syringe. Then the sealer was applied to root canal space and corresponding protaper Gutta–percha point coated with sealer was inserted to the working length. Cone is then seared off at the orifice level.

Group 3 (EndoSequence bioceramic sealer)

The EndoSequence verifier that fit the prepared canal space was selected and then the corresponding C points are used for obturation. Premixed bioceramic sealer is placed into the canal with the provided syringe tip up to 2/3rd of the canal. Matched taper cone (C points) was dipped into the sealer and placed slowly in up and down motion until it reaches the full working length. The cone is then seared off at the orifice level.

In all the samples obturating material is removed 3 mm beneath the cementum-enamel junction and restored with Cavit G (3M ESPE, Seefeld, Germany) and stored at more than 95% relative humidity at 37°C for 10 days in a humidifier. All the samples were vertically sectioned using a hard tissue microtome as the chances of crack formation in the tooth structure as well as the material will be minimal. Marginal gap at sealer and root dentin interface was evaluated under scanning electron microscope at ×2000 magnification at coronal, and apical halves of root canal.

Scanning electron microscopy analysis

The samples were mounted on an aluminum stub, sputter coated with gold and viewed under scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

To assess the marginal adaptation the following variable was measured:

Maximum gap width as the maximum distance between obturated material and root canal dentin was measured directly at ×2000 magnification by other examiner to avoid the examiner bias. The data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple post hoc test using SPSS 20, (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

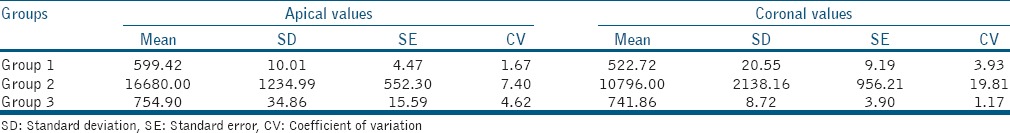

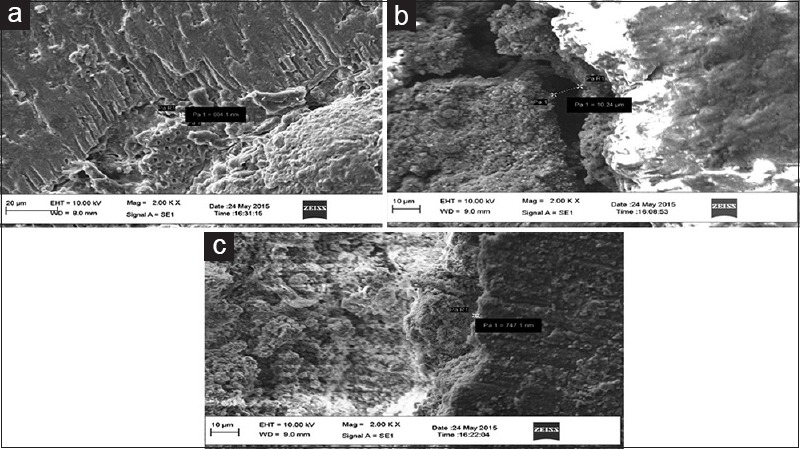

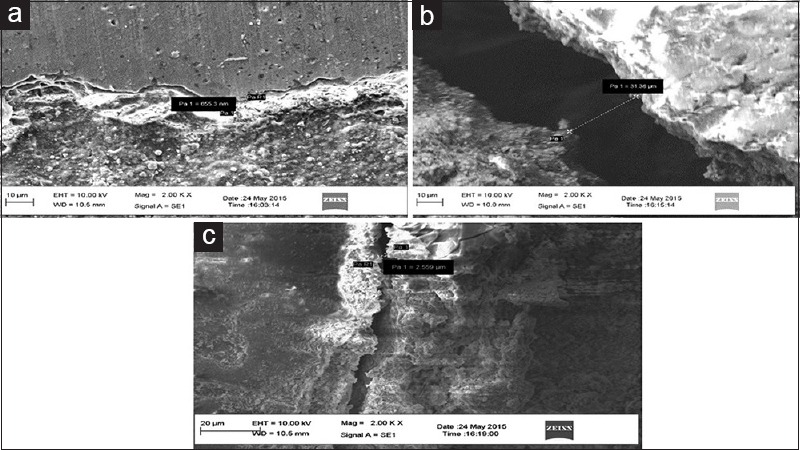

The highest marginal gap was seen in Group 2 and the lowest marginal gap was observed in Group 1 [Table 1]. Coronal halves showed superior marginal adaptation compared to apical halves in all the groups [Figures 1 and 2].

Table 1.

Summary statistics of coronal and apical values (nm) in three Groups 1, 2, 3

Figure 1.

Scanning electron microscopic images of coronal halves, (a) MM-Seal (b) mineral trioxide aggregate Fillapex (c) EndoSequence BC sealer

Figure 2.

Scanning electron microscopic images of apical halves (a) MM-Seal (b) mineral trioxide aggregate Fillapex (c) EndoSequence BC sealer

The results of this study showed that there was statistically significant difference between Group 1 and Group 2 and Group 2 and Group 3 and there was no significant difference between Group 1 and Group 3.

DISCUSSION

The main goal of obturation is to provide a three dimensional seal, thereby preventing the reinfection of root canal and preserving the health of periapical tissues.[5] Obturation with Gutta–percha along with sealer is considered to be gold standard in root canal therapy. In spite of its various advantages, it has fewer demerits like its inability to bond with root canal dentin and also due to the hydrophobic nature the sealer tends to pull away from the Gutta–percha on setting.[6]

Studies in past have evaluated the sealing ability through various microleakage methods such as dye penetration method, electrical methods, fluid filtration technique, radioisotope tracing, and marginal adaptation by SEM.[7] In this study, scanning electron microscope was utilized for marginal gap assessment. The advantage of using SEM over various microleakage methods is, in SEM the defects at the submicron level can be observed at required magnification and final evaluation can be done by preserving microphotographs.

The major function of a root canal sealer is to fill imperfections and increase adaptation of the root filling material to the canal walls, failing which the chances of leakage and failure increases. An ideal root canal sealer must be biocompatible, should have low surface tension thereby having good penetration into irregularities, better wettability thus providing fluid tight seal. About 60% of endodontic failures are due to inadequate filling of root canal space.[8] This has led to the development of new endodontic materials and obturation systems.

Adhesion of root canal sealer to root dentin is a basic requirement of any root filling material.[9] The present study used three root canal sealers, i.e., MM-Seal, MTA Fillapex and EndoSequence sealer to evaluate the marginal adaptation to root dentin. Compared to all the sealers, MM-Seal showed superior marginal adaptation and MTA Fillapex showed poor adaptation. Higher interfacial gaps were observed at the apical level of all sealer types than at the coronal level. This observation was in consistent with those of other studies.[10]

The discrepancy between the apical and coronal levels might be accounted for by the lower density and diameter of dentinal tubules found at the apical level, resulting in lower sealer penetration.[11,12] Moreover, the smear layer removal is difficult at the apical third that might act as a physical barrier which interfered with sealer adaptation to root canal dentin.[13]

Resin-based sealers have gained more popularity in recent years because these sealers penetrate deep into the dentinal tubules due to their better flowability, long setting time, and provide long-term dimensional stability. The resin sealer used in this study is MM-Seal which is an epoxy resin-based sealer exhibited less gap compared to other sealers, and these findings were in consistent with previous study.[14] The superior adaptation of MM-Seal could be due to its ability to bond to root dentin chemically by reacting with any exposed amino groups in collagen to form covalent bonds between the resin and collagen upon opening of epoxide ring.[15] Unlike alkaline bioceramic-based sealers, AH Plus is slightly acidic and might result in self-etching when in contact with dentin, thereby enhancing interfacial bonding and adaptation.[10]

Manufacturers claim that hydrophilic nature of polymeric endodontic points uses residual moisture and expands radially without expanding axially forming a self-seal on setting. And, the alkaline nature of many bioceramic by-products denature dentinal collagen fibers, which then facilitated the penetration of sealers into the dentinal tubules, in spite of better penetration, we observed the presence of marginal gaps in the samples obturated with Endosequence BC sealer. This is in correlation with the study done by Al-Haddad et al.[10] In this study, EDTA was used as the irrigant between instrumentation. It had been demonstrated that EDTA decreases the wetting ability of dentinal walls,[16] thereby producing an environment suitable for the adhesion of hydrophobic materials such as AH Plus and creating efficient micro retention. However, the decreased wetting ability of the dentin surface prohibited the adhesion of any hydrophilic materials[17] like EndoSequence bioceramic sealer.

The other sealer used in this study is MTA Fillapex, which showed statistically significant difference compared to MM-Seal and EndoSequence BC sealer groups. Sarkar et al. suggested that calcium and hydroxyl ions will be released in the presence of phosphate containing fluids which will result in the formation of apatite that promotes controlled mineral nucleation on dentin which can be seen as the formation of an interface layer with tag-like structures.[18] According to a study done by Nagas et al., there is better bonding of MTA Fillapex when the canals are finally rinsed with distilled water and blot dried with paper points to achieve moist condition.[19] However in this study, MTA Fillapex displayed little or no tags under scanning electron microscope which may be attributed to the unpredictable moisture content in the canal. The reason for the inferior marginal adaptation of MTA Fillapex could be the low adhesion of the material due to poor microtags formed on setting.[20]

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of this study apical halves showed poor adaptation regardless of the material used than the coronal halves. Epoxy resin-based MM-Seal showed good marginal adaptation than the Bioceramic sealer (EndoSequence BC sealer) and MTA Fillapex. Further studies are essential to confirm its clinical superiority.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cohen S, Burns RC, editors. Pathways of Pulp. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1991. pp. 199–201. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Razavian H, Barekatain B, Shadmehr E, Khatami M, Bagheri F, Heidari F. Bacterial leakage in root canals filled with resin-based and mineral trioxide aggregate-based sealers. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2014;11:599–603. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pawar SS, Pujar MA, Makandar SD. Evaluation of the apical sealing ability of bioceramic sealer, AH plus & epiphany: An in vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 2014;17:579–82. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.144609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehsani M, Dehghani A, Abesi F, Khafri S, Ghadiri Dehkordi S. Evaluation of apical micro-leakage of different endodontic sealers in the presence and absence of moisture. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2014;8:125–9. doi: 10.5681/joddd.2014.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar NS, Palanivelu A, Narayanan LL. Evaluation of the apical sealing ability and adaptation to the dentin of two resin-based sealers: An in vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 2013;16:449–53. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.117518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tyagi S, Mishra P, Tyagi P. Evolution of root canal sealers: An insight story. Eur J Gen Dent. 2013;2:199–218. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zafar M, Iravani M, Eghbal MJ, Asgary S. Coronal and apical sealing ability of a new endodontic cement. Iran Endod J. 2009;4:15–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muliyar S, Shameem KA, Thankachan RP, Francis PG, Jayapalan CS, Hafiz KA. Microleakage in endodontics. J Int Oral Health. 2014;6:99–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbizam JV, Trope M, Tanomaru-Filho M, Teixeira EC, Teixeira FB. Bond strength of different endodontic sealers to dentin: Push-out test. J Appl Oral Sci. 2011;19:644–7. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572011000600017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Haddad A, Abu Kasim NH, Che Ab Aziz ZA. Interfacial adaptation and thickness of bioceramic-based root canal sealers. Dent Mater J. 2015;34:516–21. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2015-049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrari M, Mannocci F, Vichi A, Cagidiaco MC, Mjör IA. Bonding to root canal: Structural characteristics of the substrate. Am J Dent. 2000;13:255–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carrigan PJ, Morse DR, Furst ML, Sinai IH. A scanning electron microscopic evaluation of human dentinal tubules according to age and location. J Endod. 1984;10:359–63. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(84)80155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Violich DR, Chandler NP. The smear layer in endodontics – A review. Int Endod J. 2010;43:2–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2009.01627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balguerie E, van der Sluis L, Vallaeys K, Gurgel-Georgelin M, Diemer F. Sealer penetration and adaptation in the dentinal tubules: A scanning electron microscopic study. J Endod. 2011;37:1576–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gade VJ, Belsare LD, Patil S, Bhede R, Gade JR. Evaluation of push-out bond strength of endosequence BC sealer with lateral condensation and thermoplasticized technique: An in vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 2015;18:124–7. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.153075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dogan Buzoglu H, Calt S, Gümüsderelioglu M. Evaluation of the surface free energy on root canal dentine walls treated with chelating agents and NaOCl. Int Endod J. 2007;40:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2006.01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hashem AA, Ghoneim AG, Lutfy RA, Fouda MY. The effect of different irrigating solutions on bond strength of two root canal-filling systems. J Endod. 2009;35:537–40. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarkar NK, Caicedo R, Ritwik P, Moiseyeva R, Kawashima I. Physicochemical basis of the biologic properties of mineral trioxide aggregate. J Endod. 2005;31:97–100. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000133155.04468.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagas E, Uyanik MO, Eymirli A, Cehreli ZC, Vallittu PK, Lassila LV, et al. Dentin moisture conditions affect the adhesion of root canal sealers. J Endod. 2012;38:240–4. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sagsen B, Ustün Y, Demirbuga S, Pala K. Push-out bond strength of two new calcium silicate-based endodontic sealers to root canal dentine. Int Endod J. 2011;44:1088–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]