Abstract

Mass spectrometry can now measure the absolute concentrations of the majority of cellular proteins without modification or labeling.

Determining the absolute abundances of proteins on a proteome-wide scale has been a long-standing goal in systems biology. Although >1,000 proteins are routinely identified in a high-resolution mass spectrometry run, quantification is typically limited to measurements of relative protein concentrations, which are inadequate for tasks such as comparing abundances across proteins or measuring molecular stoichiometries. For example, consider relative measurements of a two-fold increase in two proteins’ abundances during the course of an experiment. Absolute abundances might reveal that protein A increases from 10 to 20 copies per cell while protein B increases from 1000 to 2000; protein B is thus present at 100 times the abundance of protein A. Now, in a breakthough reported in Nature, Malmström et al.1 have developed a combined approach that enabled estimation of the absolute abundances of more than half the known proteins of the bacterial pathogen Leptospira interrogans. The authors integrate three methods for absolute quantification in a manner that will be widely applicable, even to mammalian systems, highlighting the ever-increasing capacity of mass spectrometry to analyze complex proteomes.

In a typical shotgun proteomics workflow2, a protein sample (e.g., a whole-cell lysate or a purified protein complex) is digested into peptides, and the resulting peptide mixture is partially separated by column chromatography and introduced into a mass spectrometer via electrospray ionization. Thousands of mass spectra (MS) are collected on successive samplings of the column eluate, and tandem mass spectra (MS/MS) of the strongest peaks in each MS spectrum are collected periodically. Such peaks correspond mostly to unique peptides, having been purified both by chromatography and mass spectrometry. Usually, tens of thousands of MS/MS spectra are collected and used to computationally identify the peptides’ amino acid sequences, providing a large list of peptides detected in the sample. Proteins are identified by the presence of their component peptides in this set.

In principle, a peptide’s signal intensity (the size of its MS peak) should be proportional to the abundance of the peptide, and of the corresponding protein, in the sample. However, such estimates can be erroneous due to effects such as variable sequence-dependent peptide ionization efficiencies, suppression of neighboring signals by dominant peptides, and missing observations stemming from semi-stochastic peak selection for MS/MS analyses. As a consequence, measuring absolute abundances requires additional steps (Fig. 1).

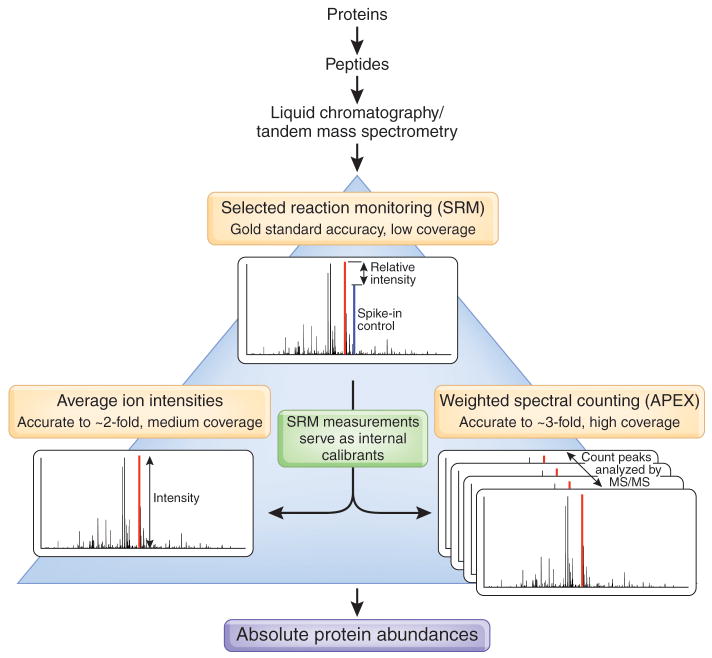

Figure 1.

Large-scale measurement of absolute protein abundances by integrating three complementary methods for quantification of mass spectrometry data. Peptides analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry provide two major types of information about molecular concentrations: the intensities of each peptide’s peaks in the mass spectra (MS), and the number of times a peptide peak is observed, reflected in the count of tandem mass spectra (MS/MS) observed for each peptide. With appropriate computational post-processing, both types of data can be used to infer absolute concentrations of the original protein. To obtain data normalized to absolute concentrations, Malmström et al.1 calibrated two large-scale methods with a small-scale, highly accurate method (SRM), which compares peak intensities of isotopically labeled and unlabeled peptides of known concentrations.

One approach, termed selected reaction monitoring3 (SRM), relies on samples spiked with isotopically labeled reference peptides for the proteins of interest. As the concentrations of the isotopically labeled reference peptides are known, relative signal intensities can be calibrated to an absolute scale. Although SRM is sensitive and highly reproducible across laboratories and platforms4, and it can theoretically be extended to a full proteome, preparing thousands of isotopically labeled peptides of known concentration is both formidable and expensive.

Two recent computational approaches that do not require isotopic labels and calculate absolute abundances from data collected in routine shotgun proteomics experiments provide an inexpensive alternative to SRM5. The first exploits MS signal intensities, the accuracy of which has greatly improved owing to recent advances in chromatography and ionization (e.g., nanoflow electrospray ionization) and in mass spectrometers themselves (e.g., the Thermo Electron Corporation LTQ/Orbitrap, which has an innovative mass analyzer6). As a consequence, Silva et al.7 found that a protein’s abundance could be well estimated from the average MS peak intensity of its three best-detected peptides. A second approach, spectral counting, analyzes the observed counts of MS/MS spectra attributable to each protein. In a recent development for large-scale absolute protein expression measurements (APEX), Lu et al.8 improved the accuracy of spectral counting by incorporating differential peptide ionization propensities into the computation.

Malmström et al.1 combine these three approaches—SRM measurements of a limited set of internal reference standards, the average MS signal intensities of the top three peptides selected per protein, and weighted MS/MS spectral counts—to more completely quantify the proteome (Fig. 1). By using the SRM measurements of reference standards to calibrate the two computational abundance calculations, they achieve ~2-fold mean abundance error for 769 proteins using the approach of Silva et al.7, and ~3-fold mean abundance error for 1,095 additional proteins with the technique of Lu et al.8. This enables them to measure abundances for >1,800 proteins, or 83% of the proteome detectable by mass spectrometry under these conditions and 51% of the predicted L. interrogans proteome (based on predicted open reading frames). Combining the high accuracy of SRM with the high coverage of the two computational approaches minimizes the costs of isotopic labeling while maximizing coverage and accuracy (Fig. 1). The abundance estimates are validated with molecule concentrations measured by single-cell cryo-electron tomography for flagellar proteins, flagellar motors and periplasmic methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein receptors.

As with any mass spectrometry method, the techniques used by Malmström et al.1 are limited by the peptides’ amenability to ionization and by the mass spectrometer’s ability to detect low abundance molecules. Although >200 of the ~1,000 proteins monitored after exposure of L. interrogans to the antibiotic ciprofloxacin changed their abundance more than twofold, the limitations of sensitivity for differentially expressed proteins may be even lower8, depending on whether the observed quantification errors are consistent across samples and systematic in nature, which is currently unknown.

While there is no theoretical upper limit to the size of the proteome for which this approach should be effective, current mass spectrometers and practices limit the approach to a few thousand proteins, which covers the majority of proteins for simple organisms, but typically represents only a fraction of the expressed proteome for higher organisms. Fractionation of samples prior to analysis can substantially increase the proteome coverage, but additional work remains to determine how fractionation affects these quantification methods; for example, the SRM calibrants might have to be chosen appropriately to sample the different fractions. Perhaps more importantly, resolving the differential expression of splice variants, which are common in proteomes of higher organisms, is still a challenging problem in shotgun proteomics. Nonetheless, given that these approaches offer protein quantification without the need for genetic modification or extensive isotopic labeling, the combination of approaches presented by Malmström et al. should be widely applicable to many systems.

The availability of absolute protein concentration data will be indispensable to fulfilling the promise of systems biology. Owing to extensive post-transcriptional regulation, protein abundances are only partially correlated with the abundances of the corresponding mRNAs8–10. This has led many to argue that direct assessment of protein levels is often more informative of the cellular state than analysis of mRNA levels. Indeed, protein abundances appear more conserved across evolution than mRNA transcript abundances10. Quantitative mass spectrometry is now poised to routinely provide such data at large scale and with high accuracy—a testament to the rapid progress in quantitative shotgun proteomics over the last few years.

Contributor Information

Christine Vogel, Center for Systems and Synthetic Biology, Institute for Cellular and Molecular Biology, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA.

Edward M Marcotte, Email: marcotte@icmb.utexas.edu, Center for Systems and Synthetic Biology, Institute for Cellular and Molecular Biology, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA. Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, USA.

References

- 1.Malmstrom J, et al. Nature. 2009;460:762–765. doi: 10.1038/nature08184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han X, Aslanian A, Yates JR., 3rd Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:483–490. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lange V, et al. Mol Syst Biol. 2008;4:222. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Addona TA, et al. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:633–641. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kito K, Ito T. Curr Genomics. 2008;9:263–274. doi: 10.2174/138920208784533647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu Q, et al. J Mass Spectrom. 2005;40:430–443. doi: 10.1002/jms.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silva JC, et al. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:144–156. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500230-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu P, et al. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:117–124. doi: 10.1038/nbt1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson L, Seilhamer J. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:533–537. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150180333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schrimpf SP, et al. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e48. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]