Abstract

Ig class switch recombination (CSR) is dependent upon the expression of activation-induced deaminase and targeted to specific isotypes by germ-line transcript expression and isotype-specific factors. NF-κB plays critical roles in multiple aspects of B cell biology and has been implicated in the mechanism of CSR by in vitro binding assays and altered S/S junctions derived from NF-κB p50-deficient mice. However, the pleiotropic contributions of NF-κB to gene expression in B cells has made discerning a direct role for NF-κB in CSR difficult. We now observe that binding of NF-κB components p50 and p65 is detected on Sγ3 in vivo following lipopolysaccharide (LPS) activation and repressed by LPS + IL–4, suggesting a direct role for this factor in CSR. In vivo footprinting confirms occupancy of a previously defined NF-κB recognition site in Sγ3 with the same temporal kinetics as found in the chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis. Binding of NF-κB components p50 and p65 was also detected on Sγ1 following B cell activation. H3 histone hyper acetylation at Sγ1 is strongly correlated with NF-κB binding, suggesting that NF-κB mediates chromatin remodeling in the Sγ3 and Sγ1 region.

Keywords: B cells, Gene rearrangements, Gene regulation, Transcription factor

Introduction

Ig class switch recombination (CSR) in B cells occurs by an intrachromosomal DNA rearrangement that focuses on stretches of repetitive switch (S) regions that are located upstream of all the CH genes except Cδ. S regions are comprised of 20–80-bp tandem repeats (TR) that are reiterated over 1–10 kb and are C-rich on the template strand [1]. In CSR, hybrid Sμ-Sx junctions are formed on the chromosome while the intervening genomic material is looped-out and excised as a circle. CSR is dependent on the expression of activation-induced deaminase (AID) and on expression of germ-line transcripts (GLT) through participating S regions (reviewed in [2]). AID-dependent double strand breaks (DSB) in S DNA are the initiating events for CSR [3–6]. To complete the switching process, recombination of the broken strands from two S regions occurs by nonhomologous end joining (reviewed in [2, 7]). Targeting of particular S regions for CSR is dependent on expression of GLT (reviewed in [8, 9]) and correlated with the expression of isotype-specific factors that facilitate CSR [10–12].

CSR and somatic hypermutation (SHM) absolutely require AID although the molecular machineries which carryout these processes are distinct [13, 14], (reviewed in [15]). AID initiates CSR and SHM through direct deamination of dC to form dU residues in single stranded DNA of target genes (reviewed in [2, 7, 8]). Differential processing of the resulting dU: dG mismatch produces mutations in V genes and DSB in S regions.

Although CSR is targeted to specific S regions through production of GLT, evidence indicates that there are additional factors that contribute to the isotype specificity of CSR. Studies of AID-dependent switch plasmids demonstrated the existence of isotype-specific switching activities and permitted mapping of a functional recombination motif (FRM) [12]. The FRM co-localized with an NF-κB recognition motif and binding of NF-κB to the FRM was detected in vitro [10–12, 16, 17]. In vivo footprinting in the Sγ3 region of unstimulated WT B cells revealed occupancy of the NF-κB recognition motifs whereas in p50-deficient B cells markedly aberrant footprints were detected [18]. Rare Sμ/Sγ3 switch junctions that form in p50-deficient B cells have decreased lengths of microhomology relative to WT cells, suggesting the involvement of this transcription factor in the mechanics of CSR [12]. However, p50 has pleiotropic affects on gene expression in B cells, including the regulation of AID gene expression [19], thus severely complicating the assignment of a direct role for NF-κB in the mechanism of CSR.

Herein we provide evidence that NF-κB components p50 and p65 interact directly with Sγ3 and Sγ1 DNA in vivo following induction of splenic B cells. In vivo footprinting of Sγ3 DNA demonstrates that the SNIP and SNAP sites are occupied with protein and that binding site occupancy follows the same binding kinetics as found by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP). Strikingly, NF-κB binding to Sγ3 DNA is repressed by IL–4. Finally we show that p50 binding to Sγ1 DNA is correlated with histone H3 hyper Ac. These findings directly implicate NF-κB in the mechanism of CSR.

Results

General remarks

Isotype switching is a dynamic process in B cells that is dependent on GLT and AID expression, DSB formation specific to S regions, and proliferation [2–4, 20]. The earliest time that completed CSR has been detected is 72 h following stimulation [21, 22]. Consequently, time points prior to 72 h of B cell activation are likely to represent predisposing events for CSR, whereas at later times these alterations may be associated with post-recombination modifications. Therefore, analyses reported here were carried out on B cells activated with LPS for 68 h or less.

NF-κB p50 homo- and heterodimers are expressed in resting and LPS-activated B cells

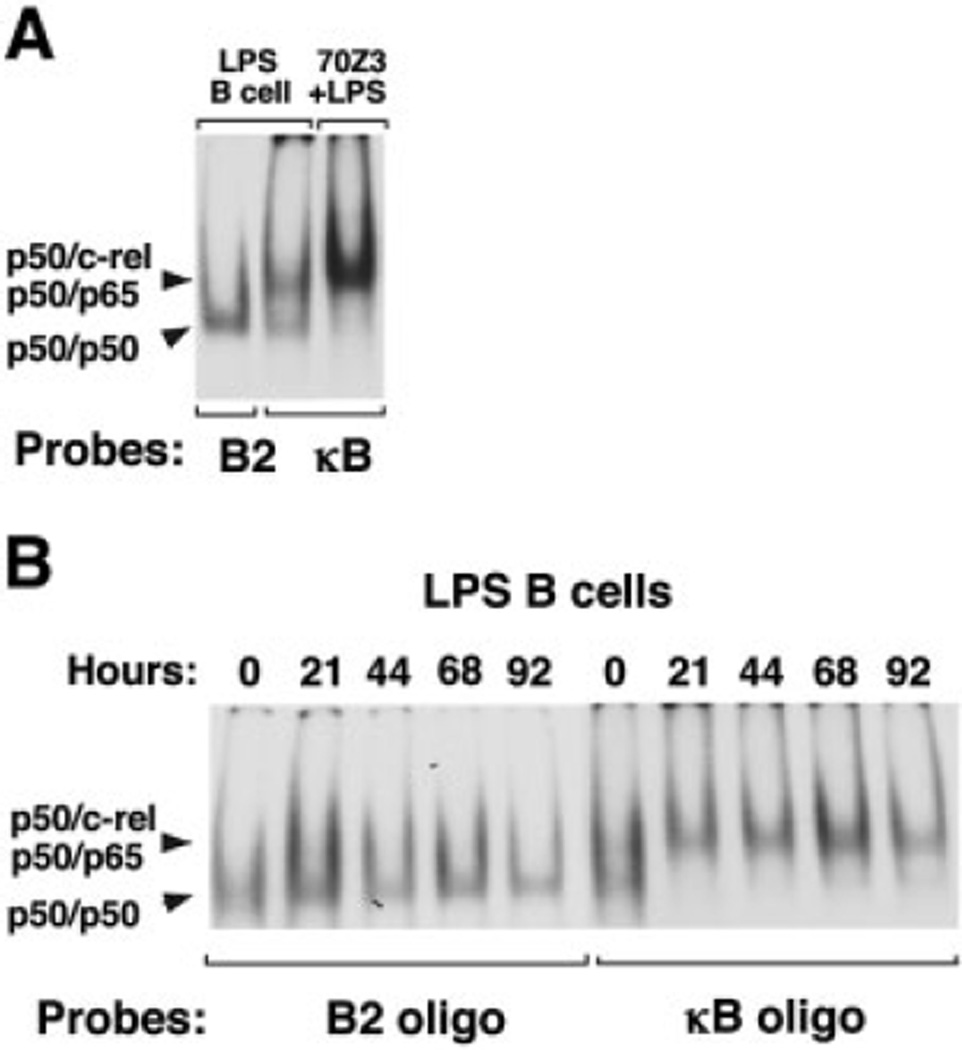

In LPS-activated splenic B cells the predominant NF-κB heterodimer is composed of p50/c-rel although some p50/p65 heterodimers are also found (Fig.1A and [23]). Ectopically expressed NF-κB components display mobilities in gel-shift assays that are essentially identical to complexes arising from endogenous NF-κB-binding activities in LPS-activated splenic B cells, indicating that NF-κB binding is direct and not through an adaptor molecule [23]. In other cell types, the most abundant form of NF-κB in activated cells is p50/p65 heterodimers whereas p50 homodimers are far less prevalent [24, 25]. However, in our in vitro binding studies, the p50 homodimer was the major binding species to Sγ DNA (Fig. 1A and [17]). To assess the relative amounts of p50 homodimers and heterodimers that are present in the nucleus of unstimulated and LPS-activated splenic B cells a time course experiment was performed in which nuclear extracts were prepared at 0, 21, 44, 68 and 92 h of stimulation. The B2 oligo represents the SNIP motif found in Sγ3 DNA whereas the κB oligo contains the classical NF-κB p50/p65-binding site [16, 17]. Using the B2 oligo probe, we find that p50 homodimers are clearly present in unstimulated splenic B cells and persist during LPS stimulation (Fig. 1B). When using the κB oligo probe we observe an equivalent ratio of p50 homo- and heterodimers in unstimulated B cells, whereas this balance shifts to favor the heterodimers in the LPS-activated B cell extracts. The affinity of p50 homodimers for the classical κB site DNA is significantly lower than that of NF-κB heterodimers such as p50/p65 [26]. Thus, the apparent 1:1 ratio of p50 homo- and heterodimers in unstimulated B cells suggests that p50 homodimers are the predominant species in these cells and that p50 heterodimers are the major species following LPS stimulation. Together, these in vitro binding results show that p50 containing homo- and heterodimers are available in both unstimulated and stimulated B cells and raise the question of which species of NF-κB are bound to Sγ3 and Sγ1 regions in vivo.

Figure 1.

NF-κB p50 homo- and heterodimers are expressed in the nuclei of resting and LPS-stimulated splenic B cells. (A) Gelshift assays were performed with nuclear extracts from splenic B cells (3.5 µg) and 70Z/3 cells (5 µg) stimulated with LPS for 44 and 72 h, respectively. Nuclear extracts were incubated with the B2 oligo and the κB oligo probes, as indicated. (B) Nuclear extracts derived from unstimulated splenic B cells or those activated with LPS for 21, 44, 68 and 92 h were analyzed in gelshift assays using the B2 oligo or the κB oligo probes, as indicated.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation indicates that NF-κB p50 and p65 are bound to Sγ3 in vivo

To determine whether NF-κB is bound directly to Sγ3 in vivo prior to CSR we performed ChIP assays with antisera raised against components of NF-κB. To ensure that the B cells used for the ChIP studies were successfully activated, Aicda transcription and GLT were assessed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR and compared to the Gapdh loading control in unstimulated splenic B cells and in LPS or LPS + IL-4-activated B cells following 48 h of stimulation (Fig. 2A). The μ and γ3 GLT are constitutively expressed in unstimulated splenic B cells, as previously observed [21]. These GLT continued their expression following LPS activation and were not affected by IL-4 treatment, whereas γ1GLT expression was IL-4 inducible. The levels of GLT and AID transcripts remain essentially constant from the 24 to 48-h time points [21]. The post-switch transcript (PST) expression profile, taken after 5 days of activation, confirms successful CSR in our B cell cultures (Fig. 2B). It should be noted that although IL-4 does not repress the γ3 GLT in LPS activated B cells it does suppress μ–>γ3 CSR (Fig. 2A and B). A representative FACS analysis of B cells stimulated with LPS and LPS+IL-4 for 4 days confirms the PST findings and indicates that these stimulation conditions specifically induce μ–>γ3 and μ–>γ1 CSR, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 2.

ChIP analysis indicates that NF-κB p50 and p65 associate with Sγ3 and Sγ1 regions. GLT (A) and post-switch transcripts (B) were analyzed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR using cDNA derived from splenic B cells that were unstimulated (Un) or activated with LPS or LPS + IL–4 for 48 h or 5 days, respectively. GLT and Aicda (A) and post-switch (B) PCR products were harvested after 33 cycles (lanes 1, 4, 7), 31 cycles (lanes 2, 5, 8), and 29 cycles (lanes 3, 6, 9). Gapdh PCR products were harvested after 30 cycles (lanes 1, 4, 7), 28 cycles (lanes 2, 5, 8), 26 cycles (lanes 3, 6, 9). (C) Schematic diagrams (not to scale) showing the γ3 and γ1 loci in the I exons, and S regions are shown. The positions of primer sets are indicated by the arrows. Open circles represent NF-κB sites. (D–F) ChIP analyses were carried out on splenic B cells that were either unstimulated (Un), or activated with LPS or LPS + IL–4 for 48 h by quantitative real time PCR and the relative enrichment was normalized to the input DNA and the nonspecific control antibody ChIP. (D) DNA were analyzed by resolving radioactively labeled PCR products by PAGE and representative gels are shown. ChIP samples were immunoprecipitated by αp50, αp65, or Ig control (Ig) and input control (In) are shown. PCR products were harvested after 35 cycles. (E) ChIP samples were analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR in duplicate and averaged. The results from five samples derived from two independent experiments are shown and the error bars represent the SEM for these samples. All ChIP PCR values were normalized against input DNA in the same sample. Pair-wise comparisons of ChIP results were analyzed using the Student's t-test and the p values were calculated. The p values indicated by one or two stars (*) were p ≤0.05 and p ≤0.005, respectively, whereas a bracket without a star indicates p = 0.07. (F) ChIP analyses using the αp50 antisera were carried out on splenic B cells that were activated with LPS for 0, 22 and 68 h. The error bars represent the SEM for these samples.

B cells were unstimulated and stimulated with LPS alone or LPS + IL-4 for 48 h, and then ChIP assays were performed with antisera raised against p50 and p65 [27]. The NF-κB-binding sites of SNIP motifs are replete throughout the Sγ3 and Sγ1 TR but the repetitive nature of S regions necessitates using primers for ChIP located immediately flanking the TR ([21] and Supplementary Fig. 2). Representative examples of radioactively labeled ChIP PCR demonstrate the association of p50 and p65 with the region immediately flanking the 3′-end of Sγ3 (Sγ3-D) TR in unstimulated and LPS-activated B cells (Fig. 2D, lanes 1, 2). To gain a quantitative characterization of NF-κB binding, the ChIP experiments were analyzed in detail by real time PCR for both immediately upstream and downstream of Sγ3 and the relative enrichment was normalized to both the input DNA and the nonspecific control antibody ChIP and the binding index was calculated. Each histogram represents the average binding index of at least five experimental samples from at least two independent experiments. The level of p50 and p65 binding was compared between unstimulated and stimulated B cells using the Student's t-test and p values are shown (Fig. 1E). We found that p50 and p65 are associated with Sγ3 DNA in unstimulated and in LPS-treated B cells whereas binding is reduced following LPS + IL-4 stimulation (Fig. 2E). These findings achieved statistical significance for p50 binding to the Sγ3 upstream and p65 binding to Sγ3 downstream regions with p values of 0.04 and 0.001, respectively. A similar trend was found for p50 binding to the Sγ3 downstream region (p = 0.07). In contrast, p50 and p65 binding to a site located 5 kb upstream of Iγ3, which is devoid of NF-κB motifs, was either undetectable or very low, respectively, demonstrating antibody specificity in the ChIP assay.

We detected statistically robust differences between unstimulated and LPS + IL-4-activated B cells for p50 and p65 binding to Sγ3. B cells stimulated with LPS alone also tended to have reduced p50 and p65 binding as compared to unstimulated B cells but these reductions did not achieve statistical significance. To further assess the kinetics of p50 binding to Sγ3 we carried out a time course experiment. ChIP was carried out at 0, 22 and 68 h of LPS stimulation. Relative to unstimulated B cells, p50 binding first decreased at 22 hours and then rebounded after 68 h of activation but the difference in binding did not achieve statistical significance (Fig. 2F). Together, these findings suggest there may be a dynamic flux of p50 binding at the Sγ3 region during an LPS response.

In vivo footprinting of Sγ3 DNA demonstrates SNIP and SNAP occupancy

NF-κB and a factor containing epitopes identical with E47 bind in vitro to SNIP and SNAP motifs located in Sγ3 DNA, respectively [17, 28]. The SNIP motif is coincident with the FRM required for LPS-induced μ–>γ3 CSR as defined in switch plasmid assays [12]. Previous in vivo footprinting studies demonstrated that the SNIP- and SNAP-binding sites in the Sγ3 region were occupied in unstimulated splenic B cells [18]. We now seek to determine whether occupancy of the SNIP and SNAP motifs changes following LPS activation and whether this change parallels the kinetics of p50 and p65 binding to the Sγ3 region revealed in the ChIP assays.

B cells stimulated with LPS for 0, 22, 68 and 92 h were analyzed in the Sγ3 region for in vivo footprints. Ligation-mediated PCR (LM-PCR) analysis identifies G residues that are either protected from or made more susceptible to methylation by protein interactions (Fig. 3A). In vivo footprinting results were observed in at least three independent experiments and protein: DNA interactions were discerned by comparison of in vivo and in vitro methylated DNA. LM-PCR analysis of the non-coding strand, located at the 5′-end of the Sγ3 region, indicates that two G residues found in the SNIP site become hypersensitive to dimethyl sulfate (DMS) methylation at 44 and 68 h of stimulation but not at earlier or later time points (Fig. 3B). In unstimulated B cells a region of protected residues on the coding strand is observed across the SNIP and SNAP recognition motifs of Sγ3 TR 39 and 38 while the flanking regions are relatively devoid of protein contacts (Fig. 3C and D) as previously reported [18]. Strikingly, B cells stimulated with LPS for 22 h exhibit an overall decrease in protected G residues and a concomitant increase in guanine residues with hypersensitivity to methylation, particularly in the region spanning the SNIP and SNAP motifs (Fig. 3C and D). This dynamic shift in the methylation pattern suggests a widening of the major groove of Sγ3 DNA, leading to greater accessibility of N7 groups of G residues to DMS. Following treatment with LPS for 68 h groups of methylation-protected residues in the SNIP and SNAP motifs re-emerge while the long spacer sequences remain largely unaffected. Comparison of the footprints over time suggests that proteins bound to Sγ3 in unstimulated cells were disengaged at the 22-h point and then re-bound to these sites at later time points. In TR 38, there are also protein contacts involving G residues at positions 268–274 located outside the SNIP- and SNAP-binding sites (Fig. 3D). This site comprises a binding motif for Nkx-2.5 a family of transcription factors that functions in cardiac tissue [29]. However, this motif is not found in multiple TR and is probably not relevant to CSR processes. Interestingly, the in vivo footprint analyses demonstrate a temporal modulation of protein: DNA interactions at the SNIP and SNAP motifs of Sγ3 DNA that follows the same binding dynamics observed for p50 by ChIP studies (Fig. 2E) and suggests that NF-κB occupies SNIP motifs in vivo.

Figure 3.

LM-PCR analysis of Sγ3 DNA in unstimulated and LPS activated splenic B cells indicates a dynamic occupancy of SNIP- and SNAP-binding sites. (A) A partial restriction map of the Sγ3 region of the IgH locus [47] is shown. The relative positions of the primers used for first strand synthesis, amplification, and labeling are indicated flanking the repetitive switch sequence. Restriction sites are abbreviated as B, BglII; H, HindIII; K, KpnI; and S, SacI. B cells were treated DMS for 1 min at 37°C. The methylated DNA were cleaved and the fragments were amplified and labeled according to the LM-PCR protocol [48]. The amplified fragments were resolved on a 4% denaturing gel and analyzed with a phosphorimager using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics). (B, C) LM-PCR was performed on the non-coding (B) and coding (C) strands of Sγ3 DNA prepared from BALB/c nu/nu splenocytes that were unstimulated or LPS activated for 22 and 68 h. DNA methylated in vitro serves as a reference for methylation in the absence of bound protein. Numbers indicate the positions relative to the 3′ end of the labeling primers, where position 1 for the coding strand is equivalent to nucleotide 2574 and position 1 for the non-coding strand is equivalent to nucleotide 505 of the germ-line Sγ3 sequence MUSIGHANA. Boxes indicate positions of the SNIP- and SNAP-binding motifs. Residues that are strongly (>50%; ●) or moderately (30–50%; ○) protected from methylation or are hypermethylated (∗) in vivo as determined by densitometry are shown. Quantitation of band intensities was performed using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics). Band intensities associated with the coding strand residues were normalized to the average intensity of residues 229–227. (D) Histograms comparing the coding strand signal intensities of ratios from in vivo and in vitro methylated DNA derived from unstimulated (upper panel) and LPS-activated 22 h (middle panel) and 68 h (lower panel) stimulated cells are shown. The light gray histogram bars indicate residues associated with the SNIP and SNAP motifs and residue numbers are indicated. (E) A summary of the methylation patterns for each time point are shown above the sequence of Sγ3 repeats 38 and 39.

NF-κB p50 and p65 binding to Sγ1 is correlated with B cell activation

In the Sγ1 locus, γ1 GLT are induced by LPS + IL-4 but not by LPS alone (Fig. 2A). Histone hyper Ac has been taken as a measure of S region accessibility [21, 30, 31]. We found that histone hyper Ac is stimulated by LPS alone and augmented by IL-4, indicating that B cell activation is sufficient to stimulate chromatin remodeling [21]. To explore the relationship between GLT expression, histone hyper Ac, and NF-κB binding at the Sγ1 region we used ChIP analysis to examine p50 and p65 binding. B cells were activated for 48 h and 5 days with LPS and LPS + IL-4 or were unstimulated. GLT RT-PCR analysis at 48 h of activation indicates that IL-4 induces transcription through the γ1 locus and the post-switch transcript RT-PCR assay demonstrates robust μ–>γ1 CSR at 5 days of culture (Fig. 2A and B) and FACS analysis confirms this conclusion (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, activation with LPS alone leads to no detectable GLT production and minimal CSR.

ChIP was carried out on B cells that were unstimulated or were stimulated for 48 h with LPS alone or LPS +IL-4 and NF-κB binding to the 3′-end of the Sγ1 region (Sγ1-D) was analyzed. Representative examples of radioactively labeled PCR demonstrate the association of p50 and p65 with the Sγ1 region in LPS and LPS + IL-4-activated B cells (Fig. 2D and Supplementary Fig. 2). In unstimulated B cells p65 binding to the 3′- end of the Sγ1 region was observed whereas p50 binding was absent. Both p50 and p65 binding to Sγ1 were induced by LPS activation and binding was not additionally enhanced by the addition of IL-4, suggesting that NF-κB binding is not regulated by GLT expression and not directly correlated with CSR.

The ChIP DNA were next analyzed in detail by quantitative PCR and the binding index was calculated. Each histogram represents the average binding index of at least five experimental samples from at least two independent experiments. ChIP analysis indicates that in unstimulated splenic B cells p50 and p65 binding to 3′-end of Sγ1 is very low whereas in activated B cells binding was induced and these differences in binding levels were statistically robust (Fig. 2E). It is noteworthy that the upstream region of Sγ1 contains TR with intact SNIP sites but degenerate SNAP motifs, which may alter the protein-binding capacity of this subregion and could account for the overall weak association of p50 and p65.

We detected statistically robust differences for p50 and p65 binding to the downstream end of Sγ1 in unstimulated B cells as compared to LPS or LPS + IL-4. The binding profile for Sγ1 is decidedly different from that found for Sγ3 where binding is high in unstimulated and LPS activated B cells but reduced following LPS + IL-4 induction. The differences for NF-κB binding to Sγ3 and Sγ1 are confirmed by statistical analyses with highly significant p values (Fig. 2E).

These studies reveal that p50 and p65 interaction with Sγ1 is not correlated with γ1 GLT expression (Fig. 2A and E). Previously, we observed that LPS activation led to hyper Ac of histones H3 and H4 at the Sγ1 region even in the absence of GLT production [21]. To further examine this issue we measured the level of H3 Ac in the S region loci, μ and γ1 using αH3 antibodies in a histone ChIP assay. We found that the global pattern of hyper Ac matches previous analyses where Ac levels are highest for Sμ and lower toward the 3′-end of the locus (Fig. 4) [21]. We also found that there was detectable H3 Ac in the Sμ locus in unstimulated cells that is correlated with the constitutive expression of μ GLT and that H3 hyper Ac is induced following LPS activation and diminished following LPS + IL-4 treatment. Sγ1 shows significant hyper Ac in response to LPS that is only slightly augmented when the cells are stimulated with LPS + IL-4, in agreement with earlier analyses (Fig. 4) [21]. It is striking that H3 histone hyper Ac is not related to GLT expression but rather correlated with NF-κB binding.

Figure 4.

Histone H3 hyper Ac is induced by LPS in the area spanning the Iγ1–Cγ1 locus. Anti-H3Ac histone antisera were used in ChIP assays carried out on nuclei derived from splenic B cells. Cells were activated with LPS or with LPS + IL–4 for 48 h or were unstimulated. A representative experiment is shown using three independent ChIP samples. All quantitative PCR values were normalized against input DNA to obtain the Ac histone index. Averaged histone Ac indices and SD downstream of the Sμ region (Sμ-D) and Sγ1 (Sγ1-D) are shown.

Discussion

Our current observations that NF-κB binds to Sγ3 DNA, that binding is repressed by IL-4, and that Sγ3 SNIP sites are occupied in LPS-activated B cells indicate a function for NF-κB and SNIP motifs in vivo during the switching process. Our data also indicate that NF-κB binding to Sγ3 is a dynamic process. Earlier in vivo footprinting studies demonstrated that SNIP and SNAP motifs were occupied by protein in unstimulated WT B cells and that aberrant footprints were detected in unstimulated p50-deficient B cells, leading us to conclude that NF-κB was bound to Sγ3 DNA prior to LPS induction [18]. Interaction of NF-κB with Sγ3 in vivo confirms earlier in vitro binding and genetic studies [12, 16–18] and permits us to conclude that NF-κB is likely to be mechanistically involved in CSR. The SNIP motif in Sγ3 DNA functions as an FRM based on studies using Sγ3/Sγ1 chimeric TR sequence in switch plasmid assays [12]. Switch plasmids carrying Sγ1 sequence are unable to support μ–>γ1 switching in LPS-activated B cells whereas this activity is present when B cells are stimulated by LPS + IL-4 [11, 12]. Remarkably, introduction of the Sγ3-associated SNIP site into a Sγ1 TR was able to restore LPS responsiveness to a switch plasmid [12]. We speculate that NF-κB recruits factors, which facilitate the recombination process.

The weight of evidence favors the view that NF-κB directly binds its cognate site in vivo. It has been shown that in vitro translated NF-κB components display mobilities in gel-shift assays that are essentially identical to those of complexes arising from endogenous NF-κB-binding activities, and that NF-κB is directly bound to its cognate binding site in cross-linking studies [23, 32]. Our studies confirm that the gel-shift patterns for NF-κB using the SNIP-binding site from Sγ3 DNA and classical κB oligo probes and nuclear extracts from LPS activated splenic B cells and 70Z/3 cells are extremely reproducible and identical to those previously reported. Moreover, crystal structures of NF-κB directly bound to its DNA recognition motif have been solved and clearly demonstrate direct factor: DNA interaction without interposition of an adaptor protein [33]. However, given the limitations of in vivo footprinting and ChIP assays, it remains a formal possibility that NF-κB is bound to its recognition motif indirectly in S regions.

Our in vivo studies indicate that there is a differential pattern of NF-κB p50 and p65 binding in the Sγ3 and Sγ1 regions and provide several additional insights. First, our results show that both p50 and p65 are bound to the Sγ3 region and loss of binding is correlated with suppression of CSR. Previous genetic analyses of NF-κB function in CSR demonstrated that p50 and p65 are required for γ3 GLT expression but could not evaluate the importance of NF-κB components to other facets of the μ–>γ3 switching process [34, 35]. Our current studies strengthen the notion that direct association of NF-κB with Sγ3 is important to the mechanism of μ–>γ3 CSR. Secondly, in Sγ1 p50 and p65 binding is strongly induced by B cell activation whereas IL-4 has little additional activating influence on binding, suggesting that NF-κB association with Sγ1 is not required for CSR. Earlier analyses indicated that NF-κB p50 deficiency does not influence μ–>γ1 switching, [34, 35] consistent with our current conclusions. Thirdly, B cell activation in the absence of γ1 GLT expression leads to both NF-κB binding and histone H3 hyper Ac at the Sγ1 locus, suggesting that chromatin modification might be directed by NF-κB binding to Sγ1.

Although NF-κB is not uniquely required for μ–>γ1 switching the observation that histone H3 hyperAc is correlated with NF-κB binding may also be relevant for understanding the function of NF-κB in μ–>γ3 recombination. It has been established that NF-κB recruits chromatin modifiers to DNA in a sequence-specific fashion [36–40]. Our observation that NF-κB binding is correlated with induced histone H3 hyperAc at Sγ1 suggests that these factors may be involved in modulating the threshold of S region accessibility. Although we have not determined whether NF-κB binding is a cause or effect of histone hyper Ac we favor the former, as recruitment of DNA sequence specific factors to S regions provides specificity for chromatin modifications leading to CSR. Highly localized changes in chromatin structure are required to promote many DNA-directed processes including transcription, replication, recombination and repair. Nucleosomes are covalently modified on the N-terminal tails of histones H3 and H4 by histone modifiers to create localized DNA accessibility to transacting factors. Indeed, modification of histones H3 and H4 are correlated with V(D)J recombination in early B cell development [41–43] and with differential targeting of downstream S regions during CSR [21, 30, 31]. A fuller description of S region specific chromatin modifications is required to better understand how these sites are rendered targets of AID attack.

Materials and methods

Mice, cell culture and RT-PCR analysis

The Animal Care and Institutional Biosafety Committee in the Office for the Protection of Research Subjects at the University of Illinois gave approval for the animal protocols used here. C57BL/6×129 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. All mice were used at 8 to 10 weeks of age. Purified splenic B cells were obtained and stimulated as described previously [10]. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was carried out as described [18]. Primers for GLT (μ, γ3, γ1), Aicda, Gapdh and post-switch transcripts (for μ–>γ3 and μ–>γ1 switching) were described [11, 14].

Gel mobility shift assays

Specific DNA-protein interactions were detected using the B2 and kB oligo probes in nuclear extracts (4.5–8.75 µg) as described [17]. For supershift assays, nuclear extracts were incubated with either immune or pre-immune serum for 3 h at 4°C. Additional, premixed components of the binding reaction were subsequently added. The anti-p50 (#1263), anti-p65 (#1226) antisera were gifts from Dr. Nancy Rice (NCI, Fredrick, MD) and their preparation was previously published [27, 44, 45]. The specificity of the antisera was confirmed using specific peptide-blocking assays [46].

ChIP and real time PCR

ChIP histone assays were performed as described [21] whereas ChIP assays for p50 and p65 were performed with modifications. Briefly, splenic B cells (1 × 107) were collected and cross-linked in 1% formaldehyde HBSS solution at room temperature for 10 min. Nuclei were sonicated and the chromatin was precleared with 80 mL Salmon Sperm DNA/Protein A Agarose-50% Slurry (Upstate Biotechnology, NY, Cat 16–157), 5 µL preimmune rabbit serum and 2 µg Salmon Sperm DNA (Invitrogen, Cat 15632–011) in total volume 2 mL for 3 h with rotation at 4°C. Then immunoprecipitations were carried out using 1/3 of precleared supernatant by rotating overnight with anti-p50, anti-p65 (gifts from N. Rice) [27, 44, 45] or control Ig (Upstate Biotechnology, NY) while one tenth of the precleared supernatant was saved for the control input PCR. Each immunoprecipitation was recovered with 50 µl Salmon sperm DNA/protein A agarose beads and then was washed and processed according to the manufacturer's protocol (Upstate Technology). DNA pellets for “bound” and “control” ChIP samples were resuspended in 30 µl TE while “input” DNA pellets were resuspended in 60 µl TE. The samples were analyzed by radioactively labeled PCR using Taq polymerase (MBI) at 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s and 72°C for 30 s for 35 cycles and resolved by PAGE and by quantitative PCR using an ABI7900HT system and SYBR Green PCR Mix (Applied Biosystems) as described [21]. Input DNA was diluted 720-fold for use in the quantitative PCR. The histone binding index = (bound-control)/input. The Sμ-D, Sγ3-U, Sγ3-D, Sγ3–5kb, Sγ1-U, Sγ1-D primer pairs were previously described and shown to work specifically in standard and real-time PCR [21]. Agarose gel analysis of quantitative PCR products for each primer pair used in ChIP analysis yielded a single band (see Supplementary Fig. 2).

In vivo footprinting

LM-PCR was carried out at the Sγ3 locus, as previously reported [18]. Quantitation of band intensities was performed using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics). Band intensities associated with the coding strand residues were normalized to the average intensity of residues 229–227. Residues showing a >50% difference of signal intensity between in vitro and in vivo samples are considered strongly protected or enhanced. Residues reproducibly diminished or enhanced in intensity by 30–50% were designated as moderately protected or hypermethylated, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants AI/GM52400 (to A. L. Kenter).

Abbreviations

- Ac

acetylation

- AID

activation-induced deaminase

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- CSR

class switch recombination

- DSB

double strand breaks

- FRM

functional recombination motif

- GLT

germ-line transcript

- LM-PCR

ligation-mediated PCR

- q

quantitative

- S

switch

- TR

tandem repeat

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available at http://www.wiley-vch.de/contents/jc_2040/2006/36294_s.pdf

References

- 1.Gritzmacher CA. Molecular aspects of heavy-chain class switching. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 1989;9:173–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kenter AL. Class switch recombination: An emerging mechanism. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2005;290:171–199. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26363-2_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wuerffel RA, Du J, Thompson RJ, Kenter AL. Ig Sgamma3 DNA-specifc double strand breaks are induced in mitogen-activated B cells and are implicated in switch recombination. J. Immunol. 1997;159:4139–4144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schrader CE, Linehan EK, Mochegova SN, Woodland RT, Stavnezer J. Inducible DNA breaks in Ig S regions are dependent on AID and UNG. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:561–568. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Catalan N, Selz F, Imai K, Revy P, Fischer A, Durandy A. The block in immunoglobulin class switch recombination caused by activation-induced cytidine deaminase deficiency occurs prior to the generation of DNA double strand breaks in switch mu region. J. Immunol. 2003;171:2504–2509. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imai K, Slupphaug G, Lee WI, Revy P, Nonoyama S, Catalan N, Yel L, et al. Human uracil-DNA glycosylase deficiency associated with profoundly impaired immunoglobulin class-switch recombination. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:1023–1028. doi: 10.1038/ni974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaudhuri J, Alt FW. Class-switch recombination: interplay of transcription, DNA deamination and DNA repair. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:541–552. doi: 10.1038/nri1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manis JP, Tian M, Alt FW. Mechanism and control of class-switch recombination. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:31–39. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stavnezer J. Molecular processes that regulate class switching. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2000;245:127–168. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-59641-4_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shanmugam A, Shi M-J, Yauch L, Stavnezer J, Kenter A. Evidence for class specific factors in immunoglobulin isotype switching. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:1365–1380. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.8.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma L, Wortis H, Kenter AL. Two new isotype specific switching factors detected for Ig class switching. J. Immunol. 2002;168:2835–2846. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kenter AL, Wuerffel R, Dominguez C, Shanmugam A, Zhang H. Mapping of a functional recombination motif that defines isotype specificity for mu–>gamma3 switch recombination implicates NF-kappaB p50 as the isotype-specific switching factor. J. Exp. Med. 2004;199:617–627. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Revy P, Muto T, Levy Y, Geissmann F, Plebani A, Sanal O, Catalan N, et al. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) deficiency causes the autosomal recessive form of the hyper-IgM syndrome (HIGM2) Cell. 2000;102:565–575. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muramatsu M, Kinoshita K, Fagarasan S, Yamada S, Shinkai Y, Honjo T. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell. 2000;102:553–563. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenter AL. Class-switch recombination: after the dawn of AID. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2003;15:190–198. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(03)00018-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kenter AL, Wuerffel R, Sen R, Jamieson CE, Merkulov GV. Switch recombination breakpoints occur at nonrandom positions in the Sgamma tandem repeat. J. Immunol. 1993;151:4718–4731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wuerffel R, Jamieson CE, Morgan L, Merkulov GV, Sen R, Kenter AL. Switch recombination breakpoints are strictly correlated with DNA recognition motifs for immunoglobulin Sgamma3 DNA-binding proteins. J. Exp. Med. 1992;176:339–349. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.2.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wuerffel RA, Ma L, Kenter AL. NF-kappa B p50-dependent in vivo footprints at Ig Sgamma3 DNA are correlated with mu>gamma3 switch recombination. J. Immunol. 2001;166:4552–4559. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dedeoglu F, Horwitz B, Chaudhuri J, Alt FW, Geha RS. Induction of activation-induced cytidine deaminase gene expression by IL-4 and CD40 ligation is dependent on STAT6 and NFkappaB. Int. Immunol. 2004;16:395–404. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rush JS, Liu M, Odegard VH, Unniraman S, Schatz DG. Expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase is regulated by cell division, providing a mechanistic basis for division-linked class switch recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:13242–13247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502779102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang L, Whang N, Wuerffel R, Kenter AL. AID dependent histone acetylation is detected in immunoglobulin S regions. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:215–226. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casellas R, Nussenzweig A, Wuerffel R, Pelanda R, Reichlin A, Suh H, Qin X-F, et al. Ku80 is required for immunoglobulin isotype switching. EMBO J. 1998;17:2404–2411. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin SC, Wortis HH, Stavnezer J. The ability of CD40L, but not lipopolysaccharide, to initiate immunoglobulin switching to immunoglobulin G1 is explained by differential induction of NF-kappaB/Rel proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:5523–5532. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang SM, Tran AC, Grilli M, Lenardo MJ. NF-kappa B subunit regulation in nontransformed CD4+ T lymphocytes. Science. 1992;256:1452–1456. doi: 10.1126/science.1604322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ten RM, Paya CV, Israel N, Le Bail O, Mattei MG, Virelizier JL, Kourilsky P, Israel A. The characterization of the promoter of the gene encoding the p50 subunit of NF-kappa B indicates that it participates in its own regulation. EMBO J. 1992;11:195–203. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phelps CB, Sengchanthalangsy LL, Malek S, Ghosh G. Mechanism of kappa B DNA binding by Rel/NF-kappa B dimers. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:24392–24399. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003784200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rice NR, Ernst MK. In vivo control of NF-kappa B activation by I kappa B alpha. EMBO J. 1993;12:4685–4695. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06157.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma L, Hu B, Kenter AL. Ig S gamma-specific DNA binding protein SNAP is related to the helix-loop-helix transcription factor E47. Int. Immunol. 1997;9:1021–1029. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.7.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen CY, Schwartz RJ. Identification of novel DNA binding targets and regulatory domains of a murine tinman homeodomain factor, nkx-2.5. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:15628–15633. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.26.15628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nambu Y, Sugai M, Gonda H, Lee CG, Katakai T, Agata Y, Yokota Y, Shimizu A. Transcription-coupled events associating with immunoglobulin switch region chromatin. Science. 2003;302:2137–2140. doi: 10.1126/science.1092481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Z, Luo Z, Scharff MD. Differential regulation of histone acetylation and generation of mutations in switch regions is associated with Ig class switching. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sc.i USA. 2004;101:15428–15433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406827101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oeth PA, Parry GC, Kunsch C, Nantermet P, Rosen CA, Mackman N. Lipopolysaccharide induction of tissue factor gene expression in monocytic cells is mediated by binding of c-Rel/p65 heterodimers to a kappa B-like site. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:3772–3781. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang DB, Phelps CB, Fusco AJ, Ghosh G. Crystal structure of a free kappaB DNA: insights into DNA recognition by transcription factor NF-kappaB. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;346:147–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sha WC, Liou HC, Tuomanen EI, Baltimore D. Targeted disruption of the p50 subunit of NF-kappa B leads to multifocal defects in immune responses. Cell. 1995;80:321–330. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90415-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snapper C, Zelazowski P, Rosas F, Kehry F, Tian M, Baltimore D, Sha W. B cells from p50/NFκB knockout mice have selective defects in proliferation, differentiation, germline CH transcription and Ig class switching. J. Immunol. 1996;156:183–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhong H, May MJ, Jimi E, Ghosh S. The phosphorylation status of nuclear NF-kappa B determines its association with CBP/p300 or HDAC-1. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:625–636. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00477-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhong H, SuYang H, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Ghosh S. The transcriptional activity of NF-kappaB is regulated by the IkappaB-associated PKAc subunit through a cyclic AMP-independent mechanism. Cell. 1997;89:413–424. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhong H, Voll RE, Ghosh S. Phosphorylation of NF-kappa B p65 by PKA stimulates transcriptional activity by promoting a novel bivalent interaction with the coactivator CBP/p300. Mol. Cell. 1998;1:661–671. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dechend R, Hirano F, Lehmann K, Heissmeyer V, Ansieau S, Wulczyn FG, Scheidereit C, Leutz A. The Bcl-3 oncoprotein acts as a bridging factor between NF-kappaB/Rel and nuclear co-regulators. Oncogene. 1999;18:3316–3323. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baek SH, Ohgi KA, Rose DW, Koo EH, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Exchange of N-CoR corepressor and Tip60 coactivator complexes links gene expression by NF-kappaB and beta-amyloid precursor protein. Cell. 2002;110:55–67. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00809-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McMurry MT, Krangel MS. A role for histone acetylation in the developmental regulation of VDJ recombination. Science. 2000;287:495–498. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5452.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morshead KB, Ciccone DN, Taverna SD, Allis CD, Oettinger MA. Antigen receptor loci poised for V(D)J rearrangement are broadly associated with BRG1 and flanked by peaks of histone H3 dimethylated at lysine 4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:11577–11582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932643100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Osipovich O, Milley R, Meade A, Tachibana M, Shinkai Y, Krangel MS, Oltz EM. Targeted inhibition of V(D)J recombination by a histone methyltransferase. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:309–316. doi: 10.1038/ni1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lyakh LA, Koski GK, Telford W, Gress RE, Cohen PA, Rice NR. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide, TNF-alpha, and calcium ionophore under serum-free conditions promote rapid dendritic cell-like differentiation in CD14+ monocytes through distinct pathways that activate NK-kappa B. J. Immunol. 2000;165:3647–3655. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.3647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rice NR, MacKichan ML, Israel A. The precursor of NF-kappa B p50 has I kappa B-like functions. Cell. 1992;71:243–253. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90353-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kochel T, Mushinski JF, Rice NR. The v-rel and c-rel proteins exist in high molecular weight complexes in avian and murine cells. Oncogene. 1991;6:615–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Szurek P, Petrini J, Dunnick W. Complete nucleotide sequence of the murine gamma3 switch region and analysis of switch recombination sites in two gamma3-expressing hybridomas. J. Immunol. 1985;135:620–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mueller PR, Wold B. In vivo footprinting of a muscle specific enhancer by ligation mediated PCR. Science. 1989;249:780–786. doi: 10.1126/science.2814500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.