Abstract

Family relationships, social interactions, and exchanges of support often revolve around the household context, but scholars rarely consider the social relevance of this physical space. In this article the author considers social causes and consequences of household disorder in the dwellings of older adults. Drawing from research on neighborhood disorder and social connectedness in later life, she describes how network characteristics may contribute to household disorder and how household disorder may weaken relationships and reduce access to support. This is explored empirically by estimating cross-lagged panel models with data from 2 waves of the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. The results reveal that household disorder reflects a lack of social support, and it leads to more kin-centered networks and more strain within family relationships. The author concludes by urging greater attention to how the household context shapes—and is shaped by—the social interactions and processes that occur within it.

Keywords: aging, family relations, housing, inequality, interpersonal relationships, social support

There's no place like home. Most people spend most of their time at home, making it a key context for daily life. The household provides the backdrop for some of the most long-standing and meaningful relationships in individuals' lives, and it sets the stage for the enactment of key social roles such as spouse, parent, and child. The household context can also be a busy hub for social interaction, through which individuals cultivate and maintain network ties, pool resources, exchange support, and exercise informal control. Finally, the household context is a critical foundation for social structure. Families are formed and children are socialized in the household, the labor force is reproduced, material goods are consumed, and the division of household labor reifies gender power relations (see, e.g., Becker, 1981; Hochschild, 1989).

Substantial bodies of research have examined these household-centric social processes, but most previous work lifts these phenomena from the space in which they occur. The consideration of physical features of housing is typically limited to studies of housing inequality. Housing studies show that socioeconomic resources, housing-related discrimination, and residential segregation contribute to disparities in homeownership and household crowding (Flippen, 2001; Rosenbaum, 1996) and exposure to housing-based hazards and toxins, which may ultimately affect economic attainment, wealth, and health (Conley, 2001; Krieger & Higgins, 2002). But characteristics of housing units may also shape—and be shaped by—the social relationships and interactions that take root there.

I therefore advance a sociophysical conceptualization of the household context, which explores how a particular set of physical features of the household environment are interrelated with social networks and access to support among older adults. Research on neighborhood context suggests that neighborhood effects on health and well-being are particularly strong in older age groups, in part because older adults have greater exposure and vulnerability to their residential environments (Robert & Li, 2001). For the growing proportion of community-residing older adults, the physically more proximate environment of the household can be a critical factor for coping with disablement, maintaining community residence, participating in social activities, and promoting overall health and well-being (Glass & Balfour, 2003; Lawton & Nahemow, 1973). However, older adults' long-term residences tend to be older and less well equipped than those of younger and middle-aged adults (Rowles, Oswald, & Hunter, 2004), and declines in health and function that accompany aging can diminish the ability to address household-based hazards.

In this study I examined the presence of a particular set of physical and ambient household conditions in the dwellings of older adults, including general household disrepair, clutter, lack of cleanliness, odor, and noise. I refer to this set of conditions as household disorder. Building from social disorganization theory and previous research on social connectedness and support in later life, I developed hypotheses about how household disorder may reflect and affect the availability of network-based resources. I tested these hypotheses using data from Waves 1 and 2 of the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP), a population-based study of community-residing older adults. I found evidence consistent with my theory in that older adults who have more social support have less household disorder. More important, I found that persons who have more disordered households subsequently have more kin-centered social networks and more strained relationships with family members. I conclude the article by discussing the relevance of these findings for a sociophysical conceptualization of the household and for policy-related efforts aimed at addressing health disparities and promoting healthy aging.

The Household as a Sociophysical Context

Treating household conditions and social processes as interrelated does not require developing new theory as much as it involves connecting previously disjointed concepts and applying existing frameworks to the household level. The tradition of ecological research dating back to the Chicago School viewed social behavior and physical characteristics of the urban environment as inextricably intertwined (e.g., Park, Burgess, & McKenzie, 1925/1984). Later research emphasized that features of the built environment can promote or constrain community-level social interaction (e.g., Jacobs, 1961/1992). More recently, social disorganization theory suggests that features of neighborhood disorder (e.g., broken windows, abandoned buildings, litter, graffiti) reflect a lack of neighborhood cohesion and informal control (Sampson & Raudenbush, 1999). At the same time, there is evidence that neighborhood disorder erodes neighborhood-level social connectedness, capital, and support (Krause, 1993; Ross, Mirowsky, & Pribesh, 2002; Steenbeek & Hipp, 2011) and reduces individuals' abilities to form and maintain personal network ties (York Cornwell & Behler, 2015). My central argument is that the interaction between physical features and social factors that has been observed at the neighborhood level also occurs within the household context.

Housing and living conditions are already recognized as intertwined with social structure, to the extent that status shapes residential choices and conditions (Conley, 2001), but little attention has been devoted to the relationship between interior living conditions and social connectedness. Most important for this article is the possibility that physical household characteristics shape individuals' access to support or social capital by facilitating or constraining social relationships. At the same time, the condition of living spaces may reflect the adequacy of personal, household, and network-based resources for addressing housekeeping and household maintenance. This interchange may be particularly relevant for community-residing older adults. In the section that follows, I narrow my focus to consider the interrelations between a particular set of interior living conditions and social networks and support within the growing population of older adults who are aging in their communities.

Aging in Household Context

By 2040, nearly one-fifth of the U.S. population will be over age 65, and the vast majority of these seniors will be aging in place, or residing independently in their long-term residences (Hayutin, Dietz, & Mitchell, 2010). In fact, about one third of older adults have lived in the same residence for at least 30 years (Bryan & Morrison, 2004). For them, later life marks the culmination of decades of exposure to particular living conditions. At the same time, life course changes such as retirement from work, loss of family and friends, and declines in health and function often contribute to a focusing of daily activities within and around the home. All told, individuals 65 and over spend about three quarters of their waking hours at home, and this increases to more than 80% of waking hours among the oldest-old (Krantz-Kent & Stewart, 2007).

Living conditions may also shape older adults' abilities to cope with health problems or functional impairment. Home modifications such as handrails and stair lifts can make it possible to adapt their dwellings to meet changing needs, accommodate social activities, and enable continued independent residence (Liu & Lapane, 2009). However, for others, physical and ambient features in their interior living spaces may threaten health, create stress, exacerbate illness, limit mobility, and hasten decline. In general, older adults' long-term dwellings tend to be older and less well equipped than those of younger and middle-aged adults (Rowles et al., 2004). Plumbing problems, inadequate heating, uneven flooring, and broken fixtures present daily challenges, stressors, and difficulties that ultimately increase risks of accidents, functional decline, and transfer to long-term care facilities (see Oswald & Wahl, 2004).

In this study I considered the social context of a set of conditions that reflect deterioration or disorganization of living spaces and may pose health risks. Household disorder includes aspects of general household disrepair as well as clutter, a lack of cleanliness, odor, and noise. Environmental health research has already pointed to the health risks of such conditions. For example, lack of cleanliness in the household may expose residents to toxins, bacteria, and allergens that can cause respiratory and infectious diseases (Fisk, Lei-Gomez, & Mendell, 2007). Clutter can impede mobility and increase the risk of falls or accidents (Sattin, Rodriguez, DeVito, & Wingo, 1998). Ambient conditions like noise and odors can cause stress (Staples, 1996) and disrupt sleep (Zaharna & Guilleminault, 2010). These conditions may be particularly hazardous for those already coping with health problems common in later life, such as respiratory illness, suppressed immune function, or limited mobility (Lawton & Nahemow, 1973).

Social Causes of Household Conditions

Previous work primarily has attributed inequalities in interior living conditions to social stratification. In fact, public health research emphasizes the importance of addressing hazardous living conditions for reducing health disparities (Krieger & Higgins, 2002). Low-income individuals and racial/ethnic minorities are more likely to reside in older and more dilapidated housing (Frumkin, 2005). Substandard housing with dwelling deficiencies such as holes in walls or flooring, a lack of central heating, inadequate sewer or septic systems, and a lack of insulation provides fertile ground for the emergence of interior conditions like mold, bacteria, allergens, odor, and noise. Low or fixed incomes make it difficult for elderly poor to afford repair work and housekeeping or maintenance services, and those who do not own their homes have less control over household conditions and fewer incentives to complete home repairs. Chronic illness, functional impairment, and cognitive decline may also limit the wherewithal or competence for completing tasks related to home maintenance or upkeep (Lawton & Nahemow, 1973; Oswald, Wahl, Martin, & Mollenkopf, 2003).

Coresidence may also shape physical conditions in the household. More than two thirds of community-dwelling older adults live with at least one other person (Administration on Aging, 2011). Across a variety of household compositions, including retired couples, women tend to do the lion's share of housekeeping (South & Spitze, 1994; Szinovacz, 2000). Thus, households containing at least one woman may be less disordered. But gender-mixed households are also likely to benefit from the performance of female-typed household tasks like cleaning and tidying and male-typed tasks such as outdoor work and home maintenance (Hochschild, 1989).

Coresidence can allow individuals to pool financial resources or exchange care and support (perhaps for an elderly individual or a young grandchild), which may reduce household disorder (Spitze, 1999; Waite & Hughes, 1999). Closer relationships among coresidents may increase flexibility and cooperation around household tasks, particularly in situations of declining health or illness (see, e.g., Allen & Webster, 2001; Piercy, 2007). However, intergenerational, mixed, or combined households may complicate household roles. An increasing share of older adults reside in such households, living with extended family or nonrelatives because of health issues or economic needs (Administration on Aging, 2011). Relationship quality with coresidents and circumstances underlying coresidence (e.g., financial necessity, cultural tradition, caregiving) may shape cooperation around housekeeping and home maintenance (Kwak, Ingersoll-Dayton, & Kim, 2012), ultimately contributing to household disorder (York Cornwell, 2014).

Most important for this study, however, is that households are not closed systems. The household often serves as a hub for social interactions with nonresident family members and friends, in particular for community-residing older adults (Wahl & Lang, 2003). Because of this, household conditions are likely intertwined with residents' social relationships and their access to social support through their social networks. A large literature points to the importance of network ties and social support for health, but the mechanisms have not been fully elaborated (Berkman, Glass, Rissette, & Seeman, 2000; Thoits, 2011). One possibility is that social ties and the availability of support may reduce household disorder for older adults residing in the community, thereby limiting exposure to household-based risks.

A wide array of network ties, including but not limited to coresidents, likely play a role in the social context of the household. Close network ties with family members and friends often encourage health-promoting behaviors through informal social control (Lewis & Rook, 1999; Umberson, 1987). To the extent that ordered living conditions are considered to be normative or that household disorder is viewed as stressful or risky, network members may exert informal control to promote ordered household conditions. The presence of (or possibility of visits from) family and friends may lead older adults to make efforts to address household problems so as to avoid embarrassment or social sanctions.

Network ties also enhance coping with challenges, which may include household conditions. Having a larger network can heighten self-esteem and perceived control (Berkman et al., 2000), which may increase proactive behaviors, including household maintenance and upkeep. Network ties can also provide access to resources, including information about services, products, or resources that enhance household maintenance, upkeep, and repairs. This may be particularly valuable as older adults experience declines in health and function that necessitate adaptations to activities related to housekeeping and maintenance. Thus, I hypothesized that, regardless of living arrangements, older adults who have larger social networks have less household disorder.

Network composition may also affect household disorder. Research in social gerontology indicates that a large proportion of family members in older adults' networks enables coordination around the provision of care or support during times of illness or need (Campbell, Marsden, & Hurlbert, 1986; Wellman & Wortley, 1990). This may include the provision of help with household maintenance or housekeeping tasks. On the other hand, having a more diverse array of network members can also be beneficial. Network ties to non-kin may be particularly important because they provide access to external resources, which could include access to a wider array of information about resources or services that could assist with addressing household problems. Based on the above mechanisms, I tested two rival hypotheses: (a) that older adults who have more kin ties have less household disorder and (b) that older adults who have more non-kin ties have less household disorder.

Not all network ties are supportive, but close relationships are likely to bring access to various forms of support or assistance (Smith & Christakis, 2008), which may help to stave off household disorder. Instrumental support, which involves help or assistance with practical tasks or problems (Thoits, 2011), may include housekeeping tasks or home repairs. For example, friends and family members who visit and observe noise, odor, clutter, lack of cleanliness, or structural problems may provide or arrange for assistance out of a concern for an older adult's safety and well-being. I therefore hypothesized that older adults who have more social support (and less negative support or relationship strain) have less household disorder. Family members are more likely than friends to provide practical support around daily tasks such as housekeeping (Lee, Ruan, & Lai, 2005; Stoller & Pugliesi, 1991; Wellman & Wortley, 1990). Consequently, support from family members may be particularly important for preventing household disorder. In the following section I explore the theoretically more intriguing possibility that household disorder shapes older adults' abilities to maintain social relationships and access support.

Social Consequences of Household Disorder

Household disorder may indirectly affect social relationships if it precipitates residential mobility. For example, the emergence of household disorder in the living spaces of older adults may be concomitant with increasing needs due to illness or functional decline. As such, disorder may signal that household tasks outweigh a resident's abilities and/or resources and the need for care or assistance. Residential mobility or changes in living arrangements could therefore result from household disorder, if residents (perhaps with the help of their family members) seek a more accommodating or supportive living situation. In extreme cases, household disorder may precipitate institutionalization of an older adult (Fulmer, Guadagno, Dyer, & Connolly, 2004). Thus, residential mobility or changes in living arrangements may be a mechanism through which household disorder affects social relationships or support (see Magdol & Bessel, 2003).

However, household disorder may also directly affect relationships with family members and friends. For one thing, household disorder may reduce social visits. Family and friends may curtail their visits to households where interior conditions make them uncomfortable, or when household disorder makes them feel unwelcome (see, e.g., Gosling, Ko, Mannarelli, & Morris, 2002). On the other hand, concerns about whether living conditions will meet social expectations may lead residents to discourage visits from friends and family. Consistent with these ideas, improved housing has been found to decrease social withdrawal (Wells & Harris, 2007). When family and friends do visit, household disorder could disrupt communication and create discomfort or strain, ultimately weakening relationships. Loud noise, for example, can make communication difficult, and clutter may limit the places where visitors can sit and talk. Because it may weaken relationships with coresidents and nonresident friends and family, I hypothesized that household disorder reduces social network size, decreases access to social support, and strains relationships with friends and family members.

An important possibility is that the effects of living conditions on social relationships vary across different types of relationships. For several reasons, household disorder is particularly likely to take a toll on relationships with non-kin ties. Ongoing exchanges of support, norms of reciprocity, and filial obligation within family relationships may lead kin ties, particularly adult children, to maintain relationships in spite of what may be uncomfortable physical conditions (see, e.g., Blieszner & Hamon, 1992; Stoller & Pugliesi, 1991; Wellman & Wortley, 1990). Moreover, family members in particular may kick into gear at the sight of clutter or disrepair in an elderly or infirm relative's home—leading to increased communication, visits, and time spent helping with household tasks. For non-kin ties, however, household disorder may be perceived as a sign of a lack of sociability or the inability to reciprocate in exchanges of support, which may create strain or weaken their relationship. Thus, I expected that household disorder strains relationships, particularly with non-kin ties. If household disorder disproportionately erodes non-kin ties, it may lead to a shift in network composition such that relationships with non-kin are lost at a higher rate than those with kin. I therefore hypothesized that household disorder leads to a kin-centered network.

Method

To explore associations between household disorder and social ties and support, I used data from the first and second waves of the NSHAP(http://www.norc.org/Research/Projects/Pages/national-social-life-health-and-aging-project.aspx). The NSHAP sample of community-residing older adults was selected using a multistage area probability design that oversampled by race/ethnicity, age, and gender (O'Muircheartaigh, Eckman, & Smith, 2009). The first wave of data collection took place in 2005–2006. NSHAP staff completed in-home interviews with 3,005 individuals, ages 57–85, achieving a response rate of 75.5%. A second wave of data collection sought to re-interview all of the original Wave 1 (W1) respondents in 2010–2011. Of the 3,005 W1 respondents, 2,548 were eligible and surviving at the time of the second wave. Of these, 136 declined to participate in Wave 2 (W2), and 150 could not be located or were unable to participate. The second wave therefore includes 2,261 respondents, generating a response rate of 75.5% of all W1 respondents and 88.8% among W1 respondents who were living and eligible for W2.

Household Disorder

NSHAP's assessment of household disorder draws from methods of systematic observation of neighborhood disorder (Sampson & Raudenbush, 1999). After completing in-home interviews with NSHAP respondents, field interviewers rated the room in which they met with the respondent on a scale from 1 to 5 for (1) cleanliness (2) orderliness (3) noise level and (4) the presence and (where applicable) unpleasantness of odor. Interviewers also indicated the overall condition of the residence, ranging from very poorly kept to very well kept. These five ratings form a household disorder scale, which had good internal consistency reliability at both waves. Cronbach's alpha was .83 at W1 and .82 at W2, and item–rest correlations were moderate to strong. To calculate W1 and W2 household disorder, the ratings at each wave were standardized and divided by the total number of nonmissing ratings for each respondent.

Two limitations of the NSHAP disorder ratings warrant consideration. First, the ratings were missing for 112 W1 respondents and 86 W2 respondents (about 9% of the longitudinal sample) who were interviewed at a location other than their own homes. To the extent that household disorder increased the likelihood of an out-of-home interview, respondents with disordered homes may be underrepresented in these data. A second limitation is the possibility of heterogeneity in interviewers' evaluations. Previous research has revealed variation in the perception of neighborhood disorder (Sampson & Raudenbush, 2004). In supplemental analyses, I found that disorder ratings do not differ by interviewer race, gender, or prior experience; neither do they reflect racial or gender-based status asymmetry between interviewer and respondent. In general, younger interviewers gave higher disorder ratings, which may reflect differences in personal standards for living conditions or in the ability to detect things like noise and odor.

To account for between-interviewer differences in the evaluation of living conditions, I adjusted W1 and W2 disorder scores by standardizing them within interviewer. Disorder ratings in the analyses below therefore represent the standardized difference between the respondent's disorder score and the mean disorder score given by his or her interviewer (i.e., z score). Therefore, a score of approximately 0 indicates that the respondent's household was about average in the eyes of the interviewer. Positive scores indicate above-average disorder, and negative scores indicate below-average disorder. Summary statistics for these and other variables in the analyses are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary Statistics for Variables Included in Analyses: National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project, Waves 1 and 2.

| Variables | Wave 1 (W1) | Wave 2 (W2) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ma or proportion | SD | N | Ma or proportion | SD | N | |

| Household disorder (interviewer-adjusted)b | -0.07 | 0.66 | 2,147 | -0.04 | 0.69 | 2,174 |

| (W1 range: −1.498, 3.435; W2 range: −1.370, 3.379) | ||||||

| Social network characteristics | ||||||

| Network size (range: 0, 5) | 3.60 | 1.45 | 2,261 | 3.80 | 1.36 | 2,261 |

| Proportion of network alters who are kin | 0.67 | 0.33 | 2,223 | 0.66 | 0.33 | 2,243 |

| Social support and strain | ||||||

| Family support (range: 1, 3) | 2.46 | 0.59 | 2,152 | 2.47 | 0.60 | 2,259 |

| Friend support (range: 1, 3) | 2.16 | 0.64 | 2,148 | 2.11 | 0.68 | 2,259 |

| Family strain (range: 1, 3) | 1.33 | 0.47 | 2,151 | 1.25 | 0.43 | 2,260 |

| Friend strain (range: 1, 3) | 1.14 | 0.30 | 2,141 | 1.09 | 0.27 | 2,258 |

| Neighborhood context | ||||||

| Percentage of households below poverty in tract | 0.14 | 0.12 | 2,253 | |||

| Respondent characteristics | ||||||

| Age, divided by 10 (range: 5.7, 8.5) | 6.71 | 0.75 | 2,261 | |||

| Female | 0.52 | 2,261 | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Black | 0.17 | 2,251 | ||||

| Hispanic, non-Black | 0.10 | 2,251 | ||||

| White or other | 0.73 | 2,251 | ||||

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 0.20 | 2,261 | ||||

| High school degree | 0.25 | 2,261 | ||||

| Some college | 0.31 | 2,261 | ||||

| College degree or higher | 0.24 | 2,261 | ||||

| Household income (thousands of dollars)c | 59.45 | 80.59 | 1,648 | |||

| Physical impairment (range: 0, 7) | 0.67 | 1.46 | 2,250 | |||

| Cognitive impairment (range: 0, 10) | 0.47 | 0.73 | 2,083 | |||

| Depressive symptoms (range: 11, 44) | 15.99 | 4.91 | 2,233 | |||

| Household composition | ||||||

| Living with spouse/partner only | 0.50 | 2,261 | ||||

| Living with spouse/partner and child(ren) | 0.08 | 2,261 | ||||

| Living with spouse/partner and other(s) | 0.06 | 2,261 | ||||

| Living alone | 0.25 | 2,261 | ||||

| Single, living with child(ren) | 0.04 | 2,261 | ||||

| Single, living with other(s) | 0.06 | 2,261 | ||||

| Residential mobility (between W1 and W2) | 0.26 | 2,260 | ||||

| Spouse/partner left household (between W1 and W2) | 0.09 | 2,261 | ||||

| “Other” left household (between W1 and W2) | 0.07 | 2,261 | ||||

Means are survey adjusted and weighted to account for probability of selection, with poststratification adjustments for nonresponse.

Household disorder scores are missing for respondents who were not interviewed in their homes (n = 114 at Wave 1 [W1] and 87 at Wave 2 [W2]).

Respondent-reported household incomes range from $0 to $1,800,000. Analytic models use logged household income to normalize the distribution, with range of 3.22 to 14.46, weighted mean of 10.58, and standard deviation of .987.

Social Connectedness

To characterize the respondent's social network at W1 and W2, I used data from the NSHAP egocentric social network roster. Respondents were asked to name up to five individuals with whom they discuss things that are important to them. The number of ties named indicates network size, or the extent to which the respondent has relatively strong, frequently accessed relationships through which important resources and social influence can flow (Straits, 2000). I also calculated network kin composition, or the proportion of network contacts who are family members. This is indicative of network strength and the network's ability to coordinate help or care (Campbell et al., 1986; Wellman & Wortley, 1990).

I considered assessments of positive social support and negative social support, or relationship strain. To capture positive support, NSHAP respondents were asked at Waves 1 and 2, “How often can you open up to [members of your family/friends] if you need to talk about your worries?” and “How often can you rely on [family/friends] for help if you have a problem?” To assess relationship strain, NSHAP respondents were asked, “How often do your [family members/friends] make too many demands on you?” and “How often do they criticize you?” Responses for each of the four support items ranged from 1 (hardly ever [or never]) to 3 (often). Following previous research (Shiovitz-Ezra & Leitsch, 2010; Walen & Lachman, 2000), I averaged the responses to the two positive support items and the two negative support items separately for friends and for family members.

Covariates

Household conditions are likely to be impacted, to some degree, by the surrounding neighborhood. To capture the socioeconomic status of the surrounding area, I included a measure of the percentage of households within the respondent's census tract that have household incomes below the poverty line, based on the 2000 U.S. census. In supplemental analyses, the respondent's type of dwelling (e.g., single-family house, apartment) was not significantly associated with disorder or social relationships, so I do not include it here.

To control for the respondent's living arrangements, I included a six-category classification of household composition at W1 based on the respondent's residence with a spouse/partner, child(ren), and “other” (nonpartner, nonchild) individuals (Waite & Hughes, 1999). Note that most (about 88%) of the coresident children of respondents in this sample are adult children, over age 18. In these households, a respondent is unlikely to be playing the same kind of parenting role as one would find in a sample of middle-aged or younger adults who live with a child or children.

As shown in Table 1, more than 25% of respondents moved between W1 and W2, and nearly one third of respondents (32.3%) experienced a change in living arrangements. Residential change could affect both household disorder and social connectedness, or it could be a mechanism through which household disorder affects social connectedness. In this study I considered residential transitions primarily as a control. All models account for whether the respondent had moved between W1 and W2, along with two of the most common changes in living arrangements: (a) the departure of the respondent's coresident spouse/partner and (b) the departure of “other” (nonpartner, nonchild) residents between W1 and W2. The latter signifies that the household was non-nuclear at W1 but limited to nuclear family members at W2.

I controlled for three aspects of respondent health at W1 that may be relevant for household maintenance, social connectedness, and support. Physical function was assessed by asking respondents about their ability to complete nine tasks, including walking one block, eating, and getting in and out of bed. The 10-item Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (Pfeiffer, 1975) assessed cognitive function, and a shortened 11-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977) captured depressive symptoms. Finally, I controlled for sociodemographic characteristics and socioeconomic status, including the respondent's racial/ethnic background, educational attainment, and income. I used the respondent's reported household income from the year prior to the W1 interview, with logged values to normalize the distribution.

Analytic Strategy

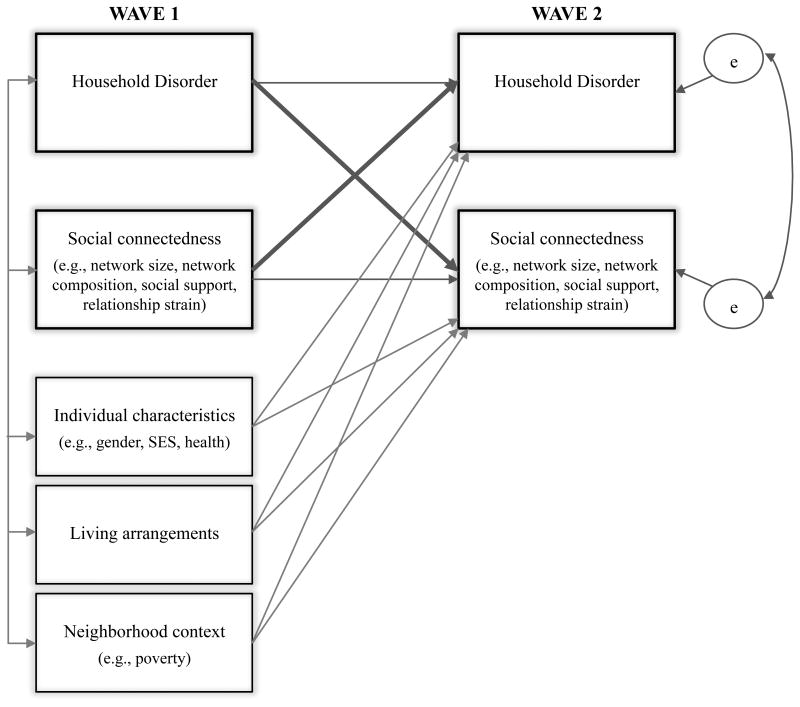

Because I theorized that household disorder and social relationships are interrelated, I specified a series of structural equation models with cross-lagged dependent variables. As depicted in Figure 1, these models simultaneously estimate the relationship between household disorder at W1 and social connectedness at W2, as well as the relationship between social connectedness at W1 and household disorder at W2. The models also accounted for living arrangements, as well as the respondent's sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics and health status at W1.

Figure 1. Cross-lagged Model of Household Disorder and Social Connectedness.

The cross-lagged panel models used full-information maximum likelihood estimation and included all of the 2,261 respondents who were interviewed at both waves. The models were adjusted for stratification and clustering at W1 and use the NSHAP-provided person-level weight, which is based on differential probabilities of selection into the study with poststratification adjustments for nonresponse. To attenuate selectivity bias due to attrition from W1 to W2, I controlled for lambda, or the probability that a W1 respondent was not included in the analysis (Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1984). I used a probit model to calculate this probability based on respondent characteristics, including age, gender, race, education, coresidents, health, and network size.

Results

My main goal was to assess the nature of the link between household disorder and social connectedness. Table 2 presents unstandardized coefficients from the cross-lagged panel analyses, as well as several indices of model fit. Chi-square tests of model fit are almost always significant when the sample size is large, as it is here (Bollen, 1989). Thus, it is important to consider other fit statistics that are less sensitive to sample size, such as the comparative fit index and the Tucker–Lewis Index. These provide reassurance; comparative fit indices and Tucker–Lewis Indices are above .95, which indicates an excellent fit to the data. The root-mean-square error of approximation tends to be larger with larger sample sizes, but those values for the models here are well below .06, which also suggests an excellent fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Table 2. Results From Cross-Lagged Models Predicting Household Disorder, Network Ties, Support, and Strain (n = 2,261).

| Predictor | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Covariance with W1 household disorder | ||||||||

| Age (in decades) | −0.03** | 0.01 | −0.03** | 0.01 | −0.03** | 0.01 | −0.03** | 0.01 |

| Female | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Race/ethnicity (ref.: White or other) | ||||||||

| Black | 0.02*** | 0.01 | 0.02*** | 0.01 | 0.02*** | 0.01 | 0.02*** | 0.01 |

| Hispanic, non-Black | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Education (ref.: less than high school) | ||||||||

| High school | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Some college | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | −0.03*** | 0.01 | −0.03*** | 0.01 | −0.03*** | 0.01 | −0.03*** | 0.01 |

| Household income (logged) | −0.13*** | 0.02 | −0.13*** | 0.02 | −0.13*** | 0.02 | −0.13*** | 0.02 |

| Census tract: percent poverty | 0.01*** | 0.00 | 0.01*** | 0.00 | 0.01*** | 0.00 | 0.01*** | 0.00 |

| Cognitive impairment | 0.04** | 0.01 | 0.04** | 0.01 | 0.04** | 0.01 | 0.04** | 0.01 |

| Depressive symptoms | 0.45*** | 0.09 | 0.45*** | 0.09 | 0.45*** | 0.09 | 0.44*** | 0.09 |

| Physical function | 0.11*** | 0.03 | 0.11*** | 0.03 | 0.11*** | 0.03 | 0.11*** | 0.03 |

| Living arrangements at W1 (ref.: partner only) | ||||||||

| Partner and child(ren) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Partner and other(s) | 0.01** | 0.00 | 0.01** | 0.00 | 0.01** | 0.00 | 0.01** | 0.00 |

| Alone | 0.02** | 0.01 | 0.02** | 0.01 | 0.02** | 0.01 | 0.02** | 0.01 |

| Single with child(ren) | 0.01* | 0.00 | 0.01* | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Single with other(s) | 0.02*** | 0.00 | 0.02*** | 0.00 | 0.02*** | 0.00 | 0.02*** | 0.00 |

| Social network size | −0.06* | 0.02 | −0.06* | 0.02 | −0.06* | 0.02 | −0.06** | 0.02 |

| Network proportion kin | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | ||

| Friend support | −0.03** | 0.01 | −0.03** | 0.01 | ||||

| Family support | −0.03** | 0.01 | −0.03** | 0.01 | ||||

| Friend strain | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Family strain | 0.02** | 0.01 | ||||||

| W1 covariates → W2 household disorder | ||||||||

| Age (in decades) | −0.08** | 0.02 | −0.08** | 0.02 | −0.09** | 0.02 | −0.08** | 0.02 |

| Female | −0.08* | 0.04 | −0.08* | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.04 |

| Race/ethnicity (ref.: White or other) | ||||||||

| Black | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Hispanic, non-Black | −0.14 | 0.07 | −0.13 | 0.07 | −0.13 | 0.08 | −0.14 | 0.07 |

| Education (ref.: less than high school) | ||||||||

| High school | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.06 |

| Some college | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.06 |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.06 |

| Household income (logged) | −0.08** | 0.02 | −0.08** | 0.02 | −0.08** | 0.06 | −0.09** | 0.03 |

| Census tract: percent poverty | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.18 |

| Cognitive impairment | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| Depressive symptoms | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Physical function | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Living arrangements at W1 (ref.: partner only) | ||||||||

| Partner and child(ren) | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.11* | 0.05 | 0.12* | 0.05 |

| Partner and other(s) | 0.26** | 0.08 | 0.27** | 0.08 | 0.27** | 0.08 | 0.28*** | 0.08 |

| Alone | 0.13** | 0.04 | 0.12** | 0.04 | 0.13** | 0.04 | 0.13** | 0.04 |

| Single with child(ren) | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.10 |

| Single with other(s) | 0.39*** | 0.09 | 0.39*** | 0.09 | 0.39*** | 0.08 | 0.37*** | 0.08 |

| Partner left household (W1–W2) | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.05 |

| Other left household (W1–W2) | −0.21* | 0.09 | −0.21* | 0.09 | −0.21* | 0.09 | −0.22* | 0.08 |

| Residential mobility (W1–W2) | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.04 |

| Social network size | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | ||

| Network proportion kin | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.05 | ||||

| Friend support | −0.00 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | ||||

| Family support | −0.07* | 0.03 | ||||||

| Friend strain | 0.12 | 0.07 | ||||||

| Cross-lagged dependent variables | ||||||||

| W1 network size → W2 disorder | −0.02 | 0.02 | ||||||

| W1 network proportion kin → W2 disorder | −0.03 | 0.05 | ||||||

| W1 family support → W2 disorder | −0.07* | 0.03 | ||||||

| W1 family strain → W2 disorder | 0.03 | 0.04 | ||||||

| W1 disorder → W2 network size | −0.04 | 0.06 | ||||||

| W1 disorder → W2 network proportion kin | 0.03* | 0.01 | ||||||

| W1 disorder → W2 family support | — | — | 0.01 | 0.02 | ||||

| W1 disorder → W2 family strain | — | — | — | 0.04** | 0.02 | |||

| W1 social variable → W2 social variablea | 0.30*** | 0.03 | 0.44*** | 0.03 | 0.31*** | 0.03 | 0.28*** | 0.03 |

| W1 disorder → W2 disorder | 0.44*** | 0.03 | 0.44*** | 0.03 | 0.43*** | 0.03 | 0.44*** | 0.03 |

| Fit statistics | ||||||||

| χ2 (df) | 1,172.73*** (47) | 1,368.33*** (49) | 1,246.21*** (53) | 1,178.38*** (57) | ||||

| Comparative fit index | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Tucker–Lewis Index | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| RMSEA [90% CI] | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | ||||

Note. Estimates are survey adjusted and weighted for the probability of selection, with poststratification adjustments for nonresponse at Wave 1 (W1). To adjust for attrition from W1 to Wave 2 (W2), each model also includes lambda, or the probability that a W1 respondent would not be included in the analysis based on a probit model predicting participation at W2. ref. = reference category; RMSEA = root-mean-square error of approximation; CI = confidence interval.

Social variable refers to the indicator of social network characteristics, support, or strain that is used as the dependent variable in the model (e.g., network size in Model 1).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

The uppermost section of Table 2 contains covariances of respondent characteristics, living arrangements, and household disorder at W1. The coefficients in the middle section present associations between W1 covariates and household disorder at W2. Finally, coefficients presented in the lower section of Table 2 test my main hypotheses that disorder and social connectedness are mutually constituted. (Relationships between W1 covariates and social connectedness at W2 were also included in the model but not shown here.)

Because disordered living conditions have not been explored much in previous research, I begin with a brief overview of variations in household disorder across respondent characteristics, neighborhood context, and living arrangements. As shown in Model 1, cognitive impairment, depression, and functional impairment were associated with household disorder at baseline, but they did not contribute to disorder at W2. Net of health status, age was negatively associated with household disorder at baseline (b = −0.03, p < .01) and at W2 (b = −0.08, p < .01). The lack of gender differences in baseline disorder (b = −0.01, ns in Model 1) is not entirely surprising, as the majority of older adults in this sample (64.7%) resided with an opposite-sex spouse or partner. I explore the role of gender in more detail below.

Household disorder reflects structural and economic inequalities. As shown in Model 1, Black respondents, respondents who did not have a college degree, and those who lived in poorer neighborhoods had higher household disorder scores at W1, but these characteristics were not associated with disorder at W2. Household income, on the other hand, was negatively associated with disorder at both W1 and W2 (for logged income, b = −0.13, p < .001 at W1 and b = −0.08, p < .01 at W2). This may reflect that higher incomes enable older adults to afford better quality housing, as well as maintenance, repair, or housekeeping services when problems arise.

Living arrangements are also associated with household disorder. Older adults whose households were limited to nuclear family members—including a spouse/partner and/or child(ren)—had the lowest household disorder scores at W1. Supplemental analyses suggest that both gender composition and social roles are relevant. For example, most respondents (56.57%) lived with just one other person. Among these, levels of disorder were lowest in female–male households (−0.20), which accounted for nearly 89% of the two-person households. However, two-female households had lower levels of disorder (0.13) than two-male (0.31) households.

As shown in Model 1, older adults who lived alone had higher disorder scores than those who lived only with a partner at both W1 (b = 0.02, p < .01) and W2 (b = 0.13, p < .01). In supplemental analyses, I found that this was true for men and women who lived alone. There is some evidence that women had less disordered households at W2 (e.g., b = −0.08, p = .03 in Model 1 and b = −0.07, p = .09 in Model 4). However, I did not find any evidence that women who lived alone had lower disorder scores than men who lived alone. (To test for gender differences in the relationship between living arrangements and household disorder, I introduced a set of interaction terms crossing gender with the six-category living arrangements variable in Model 1. None of the coefficients was significantly associated with W1 disorder or W2 disorder [e.g., for female × alone: b = .01, ns, for W1 disorder and b = −0.08, ns, for W2 disorder]).

The presence of a nonpartner, nonchild coresident was associated with more household disorder. Older adults who had at least one nonpartner, nonchild coresident at W1 had higher disorder scores at W1 and W2. This was true regardless of whether the household also contained a spouse/partner and/or children. Also, the departure of a respondent's nonpartner, nonchild coresident(s) between W1 and W2 was associated with significantly lower household disorder ratings at W2 (b = −0.21, p < .05). Put another way, respondents whose households transitioned from non-nuclear to nuclear between W1 and W2 were less disordered at W2 than those whose households were non-nuclear at both W1 and at W2. Residential mobility was not associated with disorder at W2 (b = −0.05, ns); neither was the loss or departure of a coresidential spouse/partner (b = 0.09, ns). Thus, household composition and coresidential relationships seem to be more important for household disorder than residential mobility or coresidential instability. I now turn to the main focus of this study, which was to test how household disorder shapes—and is shaped by—the broader set of social relationships with one's family and friends.

Social Networks, Support, and Household Disorder

I hypothesized that social network size, network composition, and the quality of relationships with friends and family members are associated with household disorder. I begin by considering network size. Model 1 supports my hypothesis in that network size was negatively associated with household disorder at baseline (b = −0.06, p < .01); that is, older adults who named five network members had disorder ratings more than 0.3 SD lower than older adults who named only one network member. However, as shown in the lower section of the table, social network size at W1 was not associated with household disorder at W2 (b = −0.02, ns).

Model 2 incorporates the proportion of kin ties in the network, but it was not related to household disorder at W1 (b = −0.00, ns). I also did not any find evidence for my hypotheses that having more kin ties—or having more non-kin ties—is associated with subsequent household disorder. The proportion of kin ties in the network at W1 was not associated with disorder at W2 (b = −0.03, ns).

Consistent with my hypothesis, I found that social support plays a role in household conditions. As shown in Model 3, family support was negatively associated with household disorder at baseline (b = −0.03, p < .01), as was support from friends (b = −0.03, p < .01). Also, older adults who reported more support from family members at W1 had less household disorder at W2 (b = −0.07, p < .05). However, support from friends at W1 was not associated with subsequent household disorder (b = −0.00, ns, in Model 3 of Table 2 and b = −0.01, ns, in a supplemental model with friend support as a cross-lagged dependent variable). The significant association between family support and subsequent disorder, net of baseline levels of network size, network composition, and support from friends, suggests that family support is uniquely valuable for household maintenance and upkeep.

Finally, Model 4 introduces measures of strain in relationships with friends and family members. At baseline, older adults who reported more strain in family relationships had more disordered households (b = 0.02, p < .01), but strain in relationships with friends was not associated with W1 disorder (b = 0.00, ns), and neither of the indicators of relationship strain was significantly associated with W2 household disorder (b = 0.12, ns, for friend strain; b = 0.03, ns, for family strain). Thus, older adults who had larger networks, more support from family and friends, and less strained family relationships had less disorder at baseline—but only family support contributed to the prevention of subsequent disorder.

Household Disorder and Subsequent Social Connectedness

Next, I examined whether household disorder at W1 was associated with social network characteristics, support, and strain at W2. These results are found in the bottom section of Table 2. Results from Model 1 indicate that household disorder at W1 was not associated with network size at W2 (b = −0.04, ns). However, levels of household disorder at W1 contributed to network composition at W2. Consistent with my hypothesis, disorder at W1 was positively associated with the proportion of kin ties in respondents' social networks at W2 (b = 0.03, p < .05 in Model 2). In other words, older adults who lived in more disordered dwellings at baseline were likely to have more family-centered networks 5 years later. When one compares those who had very ordered residences (i.e., adjusted disorder score of −1) with those who had very disordered residences at W1 (i.e., adjusted disorder score of 1.5), the impact of disorder is noticeable. On average, older adults with disordered residences had an increment of nearly 7 percentage points in the prevalence of kin in their networks.

I also hypothesized that household disorder decreases the availability of social support from friends and family members and increases strain in these relationships. Household disorder was not associated with a decrease in social support from family (b = .01, ns, in Model 3) or from friends (b = −0.01, ns, in a supplemental analysis). However, results in Model 4 support my hypothesis that household disorder is associated with an increase in family strain (b = 0.04, p < .01). Using the values from the example above, older adults who had very disordered residences at baseline had family strain scores that are about .10 higher, on average, than those who had very ordered households at baseline. This amounts to a difference of about 0.25 SD on the family strain scale. I hypothesized that household disorder would be particularly straining for relationships with friends, but I did not find any evidence of an association between household disorder and strain in relationships with friends (b = 0.00, ns, for the relationship between W1 household disorder and W2 friend strain in a supplemental analysis). Taken together, my findings suggest that household disorder leads to a family-centered social network at the same time that it contributes to strain within these relationships.

Residential Mobility, Social Connectedness, and Household Disorder

An important consideration is that residential mobility may complicate the relationships observed above. Although I did not find that residential mobility was associated with disorder, per se, a change in housing units could affect some of the processes through which disorder emerges. Moving residences is likely to change some of the social factors that contribute to disorder, such as access to network ties and tangible forms of support (Magdol & Bessel, 2003), which may include help with housekeeping. However, other antecedents of disorder, such as low socioeconomic status, health problems, or an overall lack of family support, may not change with residential mobility, leading disorder to reemerge in a new dwelling.

To examine whether the inclusion of movers introduces bias in the relationships I observed in Table 2, I conducted supplemental analyses on a restricted sample including only respondents who did not move between W1 and W2 (n = 1,678). The results are presented in Appendix Table A1. I found that the direction and magnitude of my main findings are robust to the exclusion of movers. Coefficients for the relationship between W1 disorder and W2 family ties and family strain retain their significance. The coefficient for the association between W1 family support and W2 disorder becomes marginally significant with the exclusion of movers (p = .06). However, this may simply reflect a loss of statistical power, due to the smaller sample of non-movers, rather than the true absence of an association. Additional analyses did not yield evidence that the relationship between family support and disorder significantly differs across movers and non-movers. More research is needed to elaborate how changes in coresidence and residential mobility are related to household disorder and how these factors may combine to shape social relationships and access to support in later life.

Discussion

My main argument in this article is that scholars need to devote more attention to the household as a sociophysical context. This is a particularly critical issue for the growing population of older adults who are aging in their long-term residences during a time of life that is characterized by changing health and shifting social connectedness. To explore the household as a physical and social context, I drew from research on neighborhood disorganization and disorder as well as previous work on social networks and support among older adults to consider the social causes and consequences of household disorder among older adults.

Household disorder is shaped by access to socioeconomic resources, health status, and living arrangements. But the focus of this study centered on the relationship between household disorder and the broader set of social connections with family and friends who do not necessarily reside in the household. On this front, I found evidence that social networks and support are relevant for household disorder. Those who have larger social networks and more supportive relationships with family and friends have less disordered households at baseline. Also, the household context is a function of social connectedness in that support from family members was negatively associated with subsequent household disorder. The unique role of family support here is consistent with research pointing to the primacy of close family members in providing instrumental support when one develops a health problem (Allen & Webster, 2001; Piercy, 2007; Stoller & Pugliesi, 1991). Thus, family support may be critical for staving off the emergence of disorder and promoting safe household conditions for community-residing older adults.

Household disorder was also associated with household composition. I found evidence that older adults who reside in non-nuclear households had more disordered residences, but those who resided with a partner and/or child have less disordered dwellings. These patterns do not seem to simply reflect gender composition but instead point to the importance of coresidential relationships. Future research should move beyond the gendered division of household labor to consider how the patterns of caregiving and support—particularly in the face of changes in health and function—shape household conditions among older adults.

Taken together, these results highlight the fact that household conditions are more than just indicators of access to economic resources or patterns of residential discrimination. Just as features of neighborhood disorder provide visual cues signifying a lack of social order or social cohesion (Ross & Mirowsky, 1999; Sampson & Raudenbush, 1999), household disorder signals that residents may face challenges that outweigh available social resources. Indeed, social service organizations often use living conditions as indicators of well-being, with features of household disorder viewed as warning signs of neglect, mistreatment, or abuse (see, e.g., Fulmer et al., 2004). In this sense, service agencies already recognize the link between physical and social features of household context that I have sought to establish in this study. However, it is important to note that the findings here suggest that seniors who lack support from family members may be particularly vulnerable to the emergence of household disorder. Targeting this group for assistance with housekeeping and household maintenance could help to break a vicious cycle of lack of support, increasing household disorder, and declining health.

The most important empirical contribution of this study is the finding that household disorder may shape older adults' social connectedness. Although household disorder does not lead to social isolation per se, disorder is linked to important shifts in network composition and relationship quality. For one thing, older adults who reside in more disordered households at baseline have networks that are more focused around family members at follow-up. Further research is needed to determine why this is the case. It is possible that individuals who have more disordered households turn their attention toward family members, or that household disorder pushes away their friends. Disorder may be particularly off-putting for non-kin, because family members are more likely to feel an obligation to maintain relationships even in uncomfortable or unpleasant settings (Blieszner & Hamon, 1992; Stoller & Pugliesi, 1991).

An alternative explanation for the relationship between household disorder and network composition stems from changes in social networks in later life. Socioemotional selectivity theory, for example, suggests that increasing age brings a preference for spending time with family members and close confidants (Charles & Carstensen, 2010). If this is the case, older adults may use household disorder to signal a lack of desire for maintaining ties with non-kin (see, e.g., Gosling et al., 2002; Valadez & Clignet, 1984). Alternatively, the emergence of household disorder may be concomitant with health problems or other challenges that lead to a focus on ties with family members because of their greater ability to coordinate care and support (Campbell et al., 1986; Schafer, 2013; Wellman & Wortley, 1990). Disconnecting from weaker ties like friends and neighbors reduces access to social capital and support, which may have detrimental effects for individual outcomes, such as health and economic attainment (Berkman et al., 2000; Granovetter, 1973). A critical avenue for further research is the consideration of how health changes may put some older adults at risk of household-based hazards and the loss of non-kin ties at a time when they may be most vulnerable to and dependent on their physical and social environments.

However, stronger ties, such as those with family members, are not impervious to household disorder. Older adults who have more disordered households at baseline reported more strained relationships with their family members at follow-up. Thus, household disorder leads to an increase in the relevance of network ties with family members, but it also contributes to strain in these relationships. From a policy standpoint, providing assistance with housing problems and household maintenance may not only reduce health risks (Oswald & Wahl, 2004) but may also help older adults cope with health problems and maintain social connectedness and access to diverse sources of social capital and support.

Previous research on housing has highlighted its role in reproducing social stratification. Social inequality, racial discrimination, and residential segregation sort individuals into housing characterized by structural deficiencies (Conley, 2001; Flippen, 2001; Rosenbaum, 1996), which may provide fertile ground for the emergence of disorder. Consistent with this, I found that Black respondents and respondents with less education endured more household disorder than their White and more educated counterparts. Also as expected, household income was negatively associated with baseline and subsequent household disorder. Inequalities in household conditions may therefore underlie disproportionate rates of network loss and turnover recently observed among Black and socioeconomically disadvantaged older adults (Cornwell, 2015), as well as persistent disparities in health and well-being.

The goal of this study was to develop a new perspective on the household, and to spark questions more than to provide definitive answers. Nevertheless, several limitations of it are worth noting. For one, I have been unable to directly explore important questions about how disorder affects coresidential relationships and household-level social processes like the division of household labor. Related to this, reliance on two waves of data did not allow me to establish a causal relationship between household disorder and social connectedness, and I cannot rule out the possibility that confounding factors, such as declines in physical or cognitive function, drive both increases in disorder and shifts in network connectedness and support. Finally, further research would benefit from consideration of more detailed indicators of housing quality, homeownership, tenure, and density—which may affect both physical and social aspects of the household—as well as aesthetic features such as housing design and furnishings.

Considering the household as a simultaneously physical and social space has implications for the many fundamental social processes that revolve around the household, such as social inequality, the household division of labor, social relationships, networks, support, and health. This approach also opens up fresh directions for research on residential contexts. Households are nested within neighborhoods, but little is known about the interrelations between the physical and social conditions of these two residential contexts. For example, the permeability of the household–neighborhood boundary may be a product of socioeconomic disadvantage and housing conditions as well as the internal social structure of the household (e.g., living arrangements, division of labor) and social networks and support. Multilevel studies of households and neighborhoods and qualitative research on social interactions in household context would help sort out the processes through which residential environments shape—and are shaped by—social relationships.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by a National Institute on Aging Predoctoral Fellowship and Pilot Funding from the Center on Demography and Economics of Aging at NORC and the University of Chicago, as well as the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. The National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project is funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01AG021487, R01AGO33903), including the National Institute on Aging, the Office of Women's Health Research, the Office of AIDS Research, and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. I am grateful to Linda Waite as well as to Kate Cagney, Benjamin Cornwell, Edward Laumann, Phil Schumm, and Richard Swedberg for comments and suggestions they provided during the development of this research.

Table A1. Results From Cross-Lagged Models Including Only Non-Movers (n = 1,678).

| Predictor | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Covariance with W1 household disorder | ||||||||

| Age (in decades) | −0.04** | 0.01 | −0.04** | 0.01 | −0.04** | 0.01 | −0.04** | 0.01 |

| Female | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Race/ethnicity (ref.: White or other) | ||||||||

| Black | 0.02*** | 0.01 | 0.02*** | 0.01 | 0.02*** | 0.01 | 0.02*** | 0.01 |

| Hispanic, non-Black | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Education (ref.: less than high school) | ||||||||

| High school | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Some college | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | −0.03*** | 0.01 | −0.03*** | 0.01 | −0.03*** | 0.01 | −0.03*** | 0.01 |

| Household income (logged) | −0.12*** | 0.02 | −0.13*** | 0.02 | −0.12*** | 0.02 | −0.12*** | 0.02 |

| Census tract: percentage poverty | 0.01*** | 0.00 | 0.01*** | 0.00 | 0.01*** | 0.00 | 0.01*** | 0.00 |

| Cognitive impairment | 0.05** | 0.01 | 0.05** | 0.01 | 0.05** | 0.01 | 0.05** | 0.01 |

| Depressive symptoms | 0.44*** | 0.10 | 0.44*** | 0.10 | 0.44*** | 0.10 | 0.44*** | 0.10 |

| Physical function | 0.14*** | 0.03 | 0.14*** | 0.03 | 0.14*** | 0.03 | 0.14*** | 0.03 |

| Living arrangements at W1 (ref.: partner only) | ||||||||

| Partner and child(ren) | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Partner and other(s) | 0.01** | 0.00 | 0.01** | 0.00 | 0.01** | 0.00 | 0.01** | 0.00 |

| Alone | 0.02** | 0.01 | 0.02** | 0.01 | 0.02** | 0.01 | 0.02** | 0.01 |

| Single with child(ren) | 0.01* | 0.00 | 0.01* | 0.00 | 0.01* | 0.00 | 0.01* | 0.00 |

| Single with other(s) | 0.01** | 0.00 | 0.01** | 0.00 | 0.01** | 0.00 | 0.01** | 0.00 |

| Social network size | −0.08** | 0.03 | −0.08** | 0.03 | −0.08** | 0.03 | −0.08** | 0.03 |

| Network proportion kin | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | ||

| Friend support | −0.03* | 0.01 | −0.03* | 0.01 | ||||

| Family support | −0.03** | 0.01 | −0.03** | 0.01 | ||||

| Friend strain | −0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Family strain | 0.02** | 0.01 | ||||||

| W1 covariates → W2 household disorder | ||||||||

| Age (in decades) | −0.07** | 0.03 | −0.07** | 0.03 | −0.07** | 0.02 | −0.07** | 0.02 |

| Female | −0.08** | 0.03 | −0.08** | 0.03 | −0.06* | 0.03 | −0.06* | 0.03 |

| Race/ethnicity (ref.: White or other) | ||||||||

| Black | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| Hispanic, non-Black | −0.10 | 0.07 | −0.10 | 0.07 | −0.10 | 0.07 | −0.11 | 0.07 |

| Education (ref.: less than high school) | ||||||||

| High school | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.07 |

| Some college | −0.05 | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.06 | −0.06 | 0.06 |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | −0.05 | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.07 | −0.06 | 0.07 | −0.06 | 0.06 |

| Household income (logged) | −0.08** | 0.07 | −0.07** | 0.02 | −0.07** | 0.02 | −0.07** | 0.02 |

| Census tract: percent poverty | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.21 |

| Cognitive impairment | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Depressive symptoms | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Physical function | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Living arrangements at W1 (ref.: partner only) | ||||||||

| Partner and child(ren) | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.12* | 0.06 | 0.12* | 0.06 |

| Partner and other(s) | 0.33*** | 0.07 | 0.33*** | 0.07 | 0.34*** | 0.07 | 0.35*** | 0.07 |

| Alone | 0.16** | 0.06 | 0.15** | 0.06 | 0.15** | 0.04 | 0.15** | 0.05 |

| Single with child(ren) | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.12 |

| Single with other(s) | 0.40** | 0.11 | 0.40** | 0.11 | 0.40** | 0.12 | 0.39** | 0.11 |

| Partner left household (W1–W2) | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| Other left household (W1–W2) | −0.22* | 0.09 | −0.22* | 0.09 | −0.22* | 0.09 | −0.23* | 0.09 |

| Social network size | −0.03* | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | ||

| Network proportion kin | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.05 | ||||

| Friend support | −0.00 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | ||||

| Family support | −0.07 | 0.04 | ||||||

| Friend strain | 0.10 | 0.07 | ||||||

| Cross-lagged dependent variables | ||||||||

| W1 network size → W2 disorder | −0.03 | 0.01 | ||||||

| W1 network proportion kin → W2 disorder | −0.04 | 0.05 | ||||||

| W1 family support → W2 disorder | −0.07 | 0.04 | — | |||||

| W1 family strain → W2 disorder | −0.01 | 0.04 | ||||||

| W1 disorder → W2 network size | −0.04 | 0.07 | ||||||

| W1 disorder → W2 network proportion kin | 0.03* | 0.01 | ||||||

| W1 disorder → W2 family support | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||||||

| W1 Disorder → W2 family strain | — | — | 0.05** | 0.02 | ||||

| W1 social variable → W2 social variablea | 0.31*** | 0.03 | 0.49*** | 0.03 | 0.28*** | 0.04 | 0.32*** | 0.03 |

| W1 disorder → W2 disorder | 0.46*** | 0.03 | 0.46*** | 0.03 | 0.46*** | 0.03 | 0.46*** | 0.03 |

| Fit statistics | ||||||||

| χ2 (df) | 995.01*** (45) | 1,156.72*** (47) | 1,015.00*** (51) | 997.47*** (55) | ||||

| Comparative fit index | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Tucker–Lewis Index | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| RMSEA [90% CI] | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | ||||

Note. Estimates are survey adjusted and weighted for the probability of selection, with poststratification adjustments for nonresponse at Wave 1 (W1). To adjust for attrition from W1 to Wave 2 (W2), each model also includes lambda, or the probability that a W1 respondent would not be included in the analysis based on a probit model predicting participation in W2. ref. = reference category; RMSEA = root-mean-square error of approximation; CI = confidence interval.

Social variable refers to the indicator of social network characteristics, support, or strain that is used as the dependent variable in the model (e.g., network size in Model 1).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

References

- Administration on Aging. A profile of older Americans: 2011. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. Retrieved from http://www.aoa.gov/Aging_Statistics/Profile/2011/docs/2011profile.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Allen S, Webster P. When wives get sick: Gender role attitudes, marital happiness, and husbands' contributions to household labor. Gender & Society. 2001;15:898–916. doi: 10.1177/089124301015006007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker GS. A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Rissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51:843–857. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blieszner R, Hamon RR. Filial responsibility: Attitudes, motivators, and behaviors. In: Dwyer JW, Coward RT, editors. Gender, families, and elder care. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1992. pp. 105–119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan TM, Morrison PA. New approaches to spotting enclaves of the elderly who have aged in place 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KE, Marsden PV, Hurlbert JS. Social resources and socioeconomic status. Social Networks. 1986;8:97–117. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8733(86)80017-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Carstensen LL. Social and emotional aging. Annual Review of Psychology. 2010;61:383–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley D. A room with a view or a room of one's own? Housing and social stratification. Sociological Forum. 2001;16:263–280. doi: 10.1023/A:1011052701810. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell B. Social disadvantage and network turnover. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2015;70:132–142. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisk WJ, Lei-Gomez Q, Mendell MJ. Meta-analyses of the associations of respiratory health effects with dampness and mold in homes. Indoor Air. 2007;17:284–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2007.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flippen CA. Racial and ethnic inequality in homeownership and housing equity. Sociological Quarterly. 2001;42:121–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2001.tb00028.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frumkin H. Health, equity, and the built environment. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2005;113:290–291. doi: 10.1289/ehp.113-a290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulmer T, Guadagno L, Dyer C, Connolly M. Progress in elder abuse screening and assessment instruments. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:297–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass TA, Balfour JL. Neighborhoods, aging, and functional limitations. In: Kawachi I, Berkman LF, editors. Neighborhoods and health. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 303–334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gosling SD, Ko SJ, Mannarelli T, Morris ME. A room with a cue: Personality judgments based on offices and bedrooms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:379–398. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter M. The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology. 1973;78:1360–1380. doi: 10.1086/225469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayutin AM, Dietz M, Mitchell L. New realities of an older America: Challenges, changes, and questions. Stanford Center on Longevity; Stanford, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild A. The second shift. New York: Avon Books; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J. The death and life of great American cities. New York: Vintage; 1992. (Original work published 1961) [Google Scholar]

- Krantz-Kent R, Stewart J. How do older Americans spend their time? Monthly Labor Review. 2007;130:8–26. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Neighborhood deterioration and social isolation in later life. International Journal of Aging & Human Development. 1993;36:9–38. doi: 10.2190/UBR2-JW3W-LJEL-J1Y5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger J, Higgins DL. Housing and health: Time again for public health action. Journal of Environmental Health. 2002;92:758–768. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak M, Ingersoll-Dayton B, Kim J. Family conflict from the perspective of adult child caregivers: The influence of gender. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2012;29:470–487. doi: 10.1177/0265407511431188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Nahemow L. Ecology and the aging process. In: Eisdorfer C, Lawton MP, editors. The psychology of adult development and aging. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1973. pp. 619–674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RPL, Ruan D, Lai G. (2005.) Social structure and support networks in Beijing and Hong Kong. Social Networks, 27. :249–274. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2005.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Rook KS. Social control in personal relationships: Impact on health behaviors and psychological distress. Health Psychology. 1999;18:63–71. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.18.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SY, Lapane KL. Residential modifications and decline in physical function among community-dwelling older adults. The Gerontologist. 2009;49:344–354. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdol L, Bessel DR. Social capital, social currency, and portable assets: The impact of residential mobility on exchanges of social support. Personal Relationships. 2003;10:149–170. doi: 10.1111/1475-6811.00043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Muircheartaigh C, Eckman S, Smith S. Statistical design and estimation for the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2009;64B:i12–i19. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald F, Wahl HW. Housing and health in later life. Reviews on Environmental Health. 2004;19:223–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald F, Wahl HW, Martin M, Mollenkopf H. Toward measuring proactivity in person–environment transactions in late adulthood: The Housing-Related Control Beliefs Questionnaire. Journal of Housing for the Elderly. 2003;10:78–93. doi: 10.1300/j081v17n01_10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park RE, Burgess EW, McKenzie RD. The city. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1984. (Originally published 1925) [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1975;23:433–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piercy KW. Characteristics of strong commitments to intergenerational family care of older adults. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007;62:S381–S387. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.6.S381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES–D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robert SA, Li LW. Age variation in the relationship between community socioeconomic status and adult health. Research on Aging. 2001;23:233–258. doi: 10.1177/0164027501232005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum E. Racial/ethnic differences in home ownership and housing quality, 1991. Social Problems. 1996;43:403–426. doi: 10.2307/3096952. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1984;79:516–524. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1984.10478078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Disorder and decay: The concept and measurement of perceived neighborhood disorder. Urban Affairs Review. 1999;34:412–432. doi: 10.1177/10780879922184004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J, Pribesh S. Disadvantage, disorder, and urban mistrust. City & Community. 2002;1:59–82. doi: 10.1111/1540-6040.00008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rowles GD, Oswald F, Hunter EG. Interior living environments in old age. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2004;23:167–193. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Systematic social observation of public spaces: A new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Sociology. 1999;105:603–651. doi: 10.1086/210356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Seeing disorder: Neighborhood stigma and the social construction of “Broken Windows. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2004;67:319–342. doi: 10.1177/019027250406700401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]