Abstract

In youth, maladaptive personality traits such as urgency (the tendency to act rashly when highly emotional) predict early onset alcohol consumption. In adults, maladaptive behaviors, including substance use, predict negative personality change. This paper reports on a test of hypothesized maladaptive, reciprocal prediction between youth drinking and the trait of urgency. In a sample of 1,906 youth assessed every six months from the spring of 5th grade through the spring of 8th grade, and again in the spring of 9th grade, the authors found such reciprocal prediction. Over each 6 month and then 12 month time lag, urgency predicted increased subsequent drinking. In addition, over 6 of the 7 time lags, drinking behavior predicted subsequent increases in urgency. During early adolescence, maladaptive personality and dysfunctional behavior each led to increases in the other. The results of this process include cyclically increasing risk for youth drinking and may include increasing risk for the multiple maladaptive behaviors predicted by the trait of urgency.

Keywords: personality change, longitudinal, drinking, urgency, early adolescents

Introduction

In youth, high-risk personality traits predict early onset substance use, including alcohol use (Settles, Zapolski, & Smith, 2014; Sher & Trull, 1994). Among emerging adults, there is evidence that dysfunctional behaviors, including substance use, predict increases in maladaptive personality traits (Horvath, Milich, Lynam, Leukefeld, & Clayton, 2004; Littlefield, Verges, Wood, & Sher, 2012; Roberts, Wood, & Caspi, 2008). These two sets of findings suggest the following hypothesis reflecting a reciprocal influence process in youth: dysfunctional behavior by youth leads to maladaptive changes in youth personality, and maladaptive personality leads to increased dysfunctional behavior by youth.

There are serious implications for psychopathology if such a process does occur in youth, in part because maladaptive personality traits increase risk transdiagnostically (Smith & Cyders, in press). This paper reports on a test of a model specifying one form of such reciprocal prediction: between the dysfunctional youth behavior of alcohol consumption and the maladaptive personality trait of urgency (the tendency to act rashly when experiencing intense emotion).

Very Early Drinking Behavior

Very early drinking behavior in youth is problematic. It concurrently predicts alcohol use disorder symptoms, tobacco and illicit drug use, risky sexual behavior, and delinquency, and it prospectively predicts alcohol use disorders, drinking and driving, negative health effects, and increased early mortality (Brown, McGue, Maggs, Schulenberg, Hingson, et al., 2008; Chung et al., 2012). Fortunately, it can be assessed validly: the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) developed a drinking screen for youth and found that for both girls and boys ages 12-15, reports of having consumed alcohol 1 or more days in the preceding year has sensitivity of 1.0 and specificity of .94 (boys) and .95 (girls) in the concurrent prediction of any past-year alcohol use disorder symptom (Chung et al., 2012). Thus, risk related to youth drinking apparently can be evaluated with simple assessment of drinking frequency.

Personality Change

Numerous studies document that personality predicts life trajectories that manifest in outcomes both positive and negative (Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi, & Goldberg, 2007). Among the many outcomes predicted by personality are physical health, mortality, marital outcomes, interpersonal functioning, educational and occupational attainment, life happiness, engagement in substance abuse, and psychopathology (Roberts et al., 2007).

In the context of the impressive overall stability of personality, there is increasing recognition that personality does change, particularly during developmental transitions. Change can occur in adaptive or maladaptive ways. Those who invest positively in their new adult roles, as reflected in job attainment, work satisfaction, and financial security tend to experience positive increases in conscientiousness and self-control (Hudson & Roberts, 2015; Roberts, Caspi & Moffitt, 2003). Those who respond negatively to the challenges of emerging adulthood, reflected in counterproductive work behaviors, including making fun of co-workers, fighting with co-workers, stealing from the workplace, or using substances at work, tend to experience decreases in emotional stability, conscientiousness, and agreeableness (Hudson & Roberts, 2015; Roberts, Walton, Bogg, & Caspi, 2006).

Theory holds that the process of personality change is likely to operate in what is sometimes called a bottom-up fashion. During developmental transitions, one takes on new social and achievement roles. Those new roles require engagement in new behaviors. Engagement in new behaviors that are reinforced by the environment leads, over time, to basic personality shifts consistent with investment in the social role and in the new behaviors (Roberts et al., 2008). For example, engagement in new behaviors such as prompt, timely arrival at work, carrying out assignments quickly and efficiently, and anticipating problems in advance a may be rewarded by the environment, perhaps in the form of a positive work performance, a raise, or a promotion. Thus, a new social role and repeated engagement in behaviors that reflect investment in that role can lead to a new environmental reward structure in which, for example, more conscientious behaviors are consistently reinforced, leading to an incremental increase in the personality trait of conscientiousness.

Urgency and Early Drinking

Concerning the trait of urgency, several aspects of the clinical science literature on urgency indicate its importance for predicting dysfunctional behaviors, including early onset alcohol use. Urgency has two facets: negative and positive urgency refer to the dispositions to act rashly when in an unusually negative or positive mood, respectively (Cyders & Smith, 2007, 2008a). Multiple meta-analyses have identified urgency or its facets as particularly strong concurrent predictors of numerous addictive behaviors, including adolescent drinking (Berg, Latzman, Bliwise & Lilienfeld, 2015; Coskunpinar, Dir & Cyders, 2013; Fischer, Smith & Cyders, 2008; Stautz & Cooper, 2013). Longitudinal studies have demonstrated that positive and/or negative urgency predict the subsequent onset of, or increases in, drinking frequency and quantity (Cyders, Flory, Rainer, & Smith, 2009; Settles et al., 2014). In addition, urgency appears to increase risk transdiagnostically: longitudinal studies have demonstrated that the trait or its facets also predict subsequent tobacco smoking, drug use, risky sex, binge eating, gambling, non-suicidal self-injury, and depression (see review by Smith & Cyders, in press). Prospective studies have documented this predictive role for urgency in children as young as late elementary school and middle school (cf. Pearson et al., 2012; Settles et al., 2014), thus suggesting that urgency's predictive role is not a downstream manifestation of scar effects from the consequences of ongoing psychopathology (Widiger & Smith, 2008).

There are empirical and theoretical reasons for hypothesizing reciprocal prediction between youth drinking and urgency. Empirically, urgency predicts subsequent drinking onset and drinking behavior in youth (Settles et al., 2014) and changes in urgency-related personality traits covary with changes in dysfunctional behavior in young adults (Hudson & Roberts, 2015). Consistent with personality change theory, early adolescent engagement in new behaviors that provide immediate reinforcement may contribute, over time, to changes in personality. Because urgency is understood to reflect a disposition to act rashly when emotional, it is plausible that increases in urgency might best be predicted by engagement in behaviors that are considered rash or impulsive in youth.

For two reasons, early drinking behavior is a good candidate for a predictor of increases in urgency. First, the behavior is rash and impulsive, in that its provision of immediate reinforcement comes at the cost of numerous negative longer-term consequences (Chung et al., 2012; Smith & Cyders, in press). Second, it is associated with engagement in numerous other impulsive behaviors (Brown et al., 2008), and may therefore serve as a marker of engagement in multiple forms of such behaviors. Because of the potency of immediate reinforcement, drinking and related behaviors are reinforced incrementally over time. Following basic personality change theory, this process can lead to gradual reinforcement of dispositions to engage in such behaviors. Urgency is one such disposition, and thus may increase over time.

It is likely that changes in other factors contribute to changes in urgency. Three possibly important factors are the experience of puberty, negative affectivity, and positive affectivity. Pubertal onset is associated with heightened reactivity to stress (Spear, 2009) and increases in risk-taking behavior (Maggs, Almeida, & Galambos, 1995); perhaps, then, pubertal status predicts increases in the disposition to act impulsively when emotional, or urgency. Elevations in negative and positive affect reflect high levels of emotionality and may, over time, lead to increases in the disposition to act rashly when highly emotional, i.e., increases in urgency. To provide a stringent test of reciprocal prediction between urgency and youth drinking, we tested such prediction controlling for prediction from these variables.

The Current Study

In a sample of 1,906 youth assessed every six months from the spring of 5th grade (elementary school) through the spring of 8th grade, and then 12 months later in the spring of 9th grade (high school), we tested a model of reciprocal prediction. We tested whether urgency at one wave predicted increased drinking the following wave and whether drinking at one wave predicted increases in urgency the following wave. We tested for these predictive effects above and beyond two sets of controls. The first was autoregressive prediction (e.g., urgency in spring, 5th grade predicting urgency in fall, 6th grade). Thus, we tested whether drinking at one wave predicted urgency the next wave beyond all the factors the contributed to urgency levels at the first wave. The second set of controls was the inclusion of pubertal status, negative affect and positive affect as predictors of urgency change and drinking change.

Method

Sample

Participants were 1906 youth in 5th grade at the start of the study; the sample was equally divided between girls and boys, and at wave 1 most participants were 11 years old. Additional information on the methodology of this study, including more detailed descriptions of the sample, measures, procedure, and data analytic approaches, is available in the online supplement.

Measures

UPPS-R-Child Version, Positive Urgency and Negative Urgency Scales (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001; Zapolski, Stairs, Settles, Combs, & Smith, 2010)

Positive and negative urgency were each assessed with 8 items using a 4 point likert-type scale. Validity information for the scales is referenced above. The traits are facets of a single domain. In the current sample, the two correlated highly: r = .63, p < .001 at wave 1, with higher correlations in subsequent waves. Each of the predictive models we report was also run with each of the two traits individually. Results were the same across traits. Accordingly, we report all results using the overall trait of urgency.

Drinking Styles Questionnaire (DSQ: Smith, McCarthy, & Goldman, 1995)

The DSQ measures drinking frequency with a single item asking how often one drinks alcohol.

The Pubertal Development Scale (PDS; Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988)

We used the common dichotomous classification of the PDS (Culbert, Burt, McGue, Iacono, & Klump, 2009) as pre- pubertal or pubertal, indicative of pubertal onset.

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule- Child Version (PANAS-C; Laurent et al., 1999)

was used to measure positive and negative affectivity in children, and each scale was internally consistent in this study (α = .89 and .90, respectively).

Procedure and Data Analysis

Participants were administered questionnaires at eight time points in 23 public elementary schools at wave 1, in 15 middle schools at waves 2-7, and at 7 high schools in wave 8. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test the model of reciprocal influence between drinking and urgency, which involved proceeding through a series of model tests. Each model allowed for cross-sectional correlations between all variables or disturbance terms.

Preliminary analyses indicated that positive affect did not predict either subsequent urgency or drinking behavior, and so was excluded from the models we present. Thus, the first, baseline model specified autoregressive predictions within urgency, drinking, puberty and negative affect. For the second model, the predictive pathway from urgency, negative affect, and pubertal status at each wave to drinking behavior the following wave was added. This model tested the degree to which urgency, negative affect, and pubertal status predicted subsequent increases in drinking over each interval during the four-year period.

The third model added in prediction of personality change from drinking, negative affect, and pubertal status. The key hypothesis was that drinking behavior at each wave would predict urgency scores the next wave. This sequence of models was tested with Mplus (Muthén &, Muthén, 2004-2010). We modeled drinking frequency as an ordered categorical variable. Pubertal status was measured as dichotomous, and both urgency and negative affect were measured on an interval scale. Improved model fit was assessed by the values of the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) for each model; the model with the lowest AIC and BIC values is preferred.

Results

Attrition and Treatment of Missing Data

At each wave, over 94% of participants from the preceding wave participated, resulting in an overall, 8-wave retention rate of 75%; detailed retention data is available in Table S1 of the online supplement. Those who participated at all waves did not differ from those who participated in fewer waves on any study variables, thus we used expectation maximization (EM) procedure to impute values for the missing data points (Little & Rubin, 1989).

Descriptive Statistics

The internal consistency of urgency at Wave 1 (fall of 5th grade) was α = .91, and became increasingly higher at subsequent waves. Correlations between urgency scores measured at adjacent waves were high, ranging from .57 to .70, indicating considerable construct stability over the eight waves and 4-year time period.

Table 1 presents descriptive participant statistics on urgency scores, engagement in drinking behavior, pubertal status, and negative affect. Consistent with previous data and with our hypotheses, engagement in drinking behavior increased steadily over time, from 12% at Wave 1 to 17% at Wave 4 and 48% at Wave 8. Supplement Table S2 provides bivariate correlations among study variables at each wave.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of key variables measured at all waves, all participants (N = 1906)

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | Wave 5 | Wave 6 | Wave 7 | Wave 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urgency Scores Mean (SD) | 4.35 (1.30) | 4.15 (1.33) | 4.21 (1.38) | 4.24 (1.36) | 4.24 (1.38) | 4.25 (1.34) | 4.27 (1.34) | 4.34 (1.27) |

| Drinker status (dichotomous) | 12.0% | 11.3% | 14.3% | 17.1% | 21.4% | 30.9% | 31.8% | 47.6% |

| Drinking = 0 | 88.0% | 88.7% | 85.7% | 82.9% | 78.6% | 69.1% | 68.2% | 53.4% |

| Drinking = 1 | 10.5% | 9.9% | 12.3% | 13.4% | 16.5% | 22.1% | 22.5% | 31.3% |

| Drinking = 2 | 0.7% | 1.1% | 1.4% | 2.4% | 2.4% | 5.3% | 6.1% | 9.2% |

| Drinking = 3 | 0.5% | 0.2% | 0.5% | 0.8% | 0.9% | 2.4% | 2.2% | 4.2% |

| Drinking = 4 | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.5% | 0.6% | 1.2% | 1.0% | 1.9% |

| Drinking = 5 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Pubertal Status (girls) | 23.7% | 31.1% | 42.1% | 48.9% | 61.8% | 62.8% | 72.4% | 80.4% |

| Pubertal Status (boys) | 22.9% | 33.3% | 42.1% | 51.9% | 62.8% | 63.5% | 74.3% | 78.8% |

| Negative Affect Mean (SD) | 2.11 (.76) | 1.82 (.74) | 1.75 (.70) | 1.69 (.73) | 1.70 (.70) | 1.72 (.68) | 1.77 (.75) | 1.83 (.76) |

Note. Drinker status is represented by the percentage of individuals who endorsed engaging in that behavior at all at each wave. Levels of drinking behavior engagement are represented by percentages of individuals who engaged in drinking behavior at different levels of the count variable. For drinking, 0 = “I have never had a drink of alcohol,” 1 = “I have only had 1, 2, 3, or 4 drinks of alcohol in my life,” 2 = “I only drink alcohol 3 or 4 times a year,” 3 = “I drink alcohol about once a month,” 4 = “I drink alcohol once or twice a week,” and 5 = “I drink alcohol almost daily.” Puberty scores represent percentage of participants considered pubertal at each wave.

Testing the reciprocal influence of drinking and personality

In the baseline model, all autoregressive pathways within urgency, drinking, pubertal status, and negative affect between waves were significant and of large magnitude. At Step 2, pubertal status was a significant predictor of drinking for four of the seven time-lags; negative affect did not predict drinking across any time lag. Each of the seven time-lagged predictive pathways from urgency to drinking was significant: urgency consistently predicted increases in drinking behavior across each time-lag, and did so beyond the effects of prior drinking, pubertal status, and affect. As shown in supplement Table S4, AIC and BIC scores were lower in Step 2, indicating improved model fit.

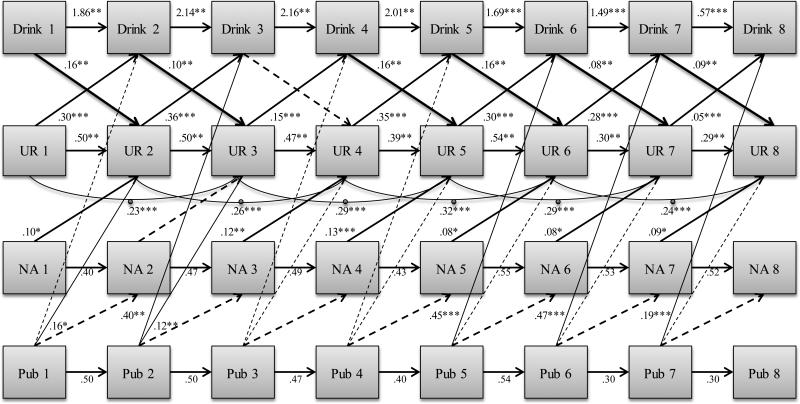

At Step 3, we added predictive pathways from drinking behavior, pubertal status, and negative affect at each wave to urgency scores at the following wave. Pubertal status predicted increased urgency scores only in the earliest two waves. Negative affect predicted increased urgency scores across 6 of the 7 waves. Above and beyond these predictions and prediction from prior urgency levels, drinking predicted increased urgency scores also across 6 of the 7 time-lags. AIC and BIC scores were lowest in Step 3 (Table S4). The model reflecting reciprocal prediction between youth drinking and urgency provided the best fit to the data. Figure 1 provides the final model and all prediction coefficients; the magnitude of the predictive effect from drinking to urgency scores is reflected in unstandardized coefficients. Because urgency values reflect average items scores, a coefficient of .16 indicates that with a one unit increase in the drinking variable, the average urgency item score increased by .16 units.

Figure 1. Reciprocal model between drinking frequency, urgency, negative affect, and puberty at all waves.

Note. UR 1 = Urgency at Wave 1, Drink 1 = drinking behavior at Wave 1, NA 1 = negative affect at Wave 1, Pub 1 = pubertal status at Wave 1. Bolded lines represent significant pathways of the main hypothesis test: drinking leading to urgency change; solid lines represent significant pathways; dashed lines represent non-significant pathways; curved lines with points represent autoregressive pathways predicting urgency from urgency scores two waves prior. Predictions from negative affect at each wave to drinking behavior at the subsequent waves were included in the model test but none of those pathways were significant, and are therefore not included in this figure. Tables S-5 to S-7 of the online supplement provides 95% confidence intervals for each of the path estimates. * p < .01 ** p < .01 *** p < .001.

We also tested whether time-lagged predictions from urgency to drinking and from drinking and negative affect to urgency were equal across waves. Imposing a constraint of inequality reduced fit significantly (results not shown). Thus, the time-lagged effects did not appear to be of the same magnitude at each wave.

Discussion

The current study is the first to find reciprocal prediction between engagement in a dysfunctional behavior (youth drinking) and endorsement of the maladaptive personality trait of urgency. The reciprocal prediction was consistently positive. Urgency consistently predicted further increases in drinking behavior and drinking consistently predicted further increases in the trait of urgency. This pattern reflects ongoing increases in dysfunction and risk. Because elevations in urgency increase risk transdiagnostically (Smith & Cyders, in press), it appears that youth drinking anticipates risk for dysfunction transdiagnostically. Strikingly, it operated over short intervals: six of the seven time-lagged predictions spanned six months. No prior study has documented this rapid, reciprocal prediction between a specific behavior and a broad personality trait.

Assessment of drinking frequency is becoming more common and is now recommended practice for pediatricians. The American Academy of Pediatricians (AAP) adopted the NIAAA drinking screener and recommends that pediatricians use it during regular check-ups (AAP & National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, NIAAA, 2011). Risk related to youth drinking can be evaluated with simple assessment of drinking frequency, and this assessment may be even more useful than previously appreciated, given that youth drinking appears to anticipate negative personality change.

It is useful to consider the current findings in their broad developmental context, because doing so suggests possible mechanisms of change. Early adolescence is a time of rapid physical and social development, characterized by a dense spacing of significant life events to which an individual must adapt. Periods of transition often require repeated engagement in new behaviors in order to respond to an individual's changing environment and his or her new place in it. This rapid succession of novel stimuli and different behavior engagement, combined with an increased emphasis placed on peer relationships, often lead early adolescents to adopt new social roles and new self-images. This complex process of engaging in new behaviors and seeing oneself differently can lead to change in what are otherwise stable personality characteristics of youth. In the case of drinking behavior and urgency, the process of personality change appears only to be occurring for the small percentage of youth who begin drinking very early; overall, urgency levels remain stable across the longitudinal period. Models of personality change will need to be developed that can explain and predict such rapid personality change for those youth. Among the important questions include whether such rapid change is specific to the early adolescent developmental period, or whether it can be documented across other age spans.

With respect to drinking and personality change, it may thus be the case that youth drinking operates as a marker for a wide range of maladaptive adjustment behaviors that might influence negative personality change. Youth are likely to experience immediate reinforcement from engaging in a number of risk behaviors, including alcohol consumption, have such reinforcement modeled by their friends as well, and also experience changes in self-perception. In this way, the current findings appear to be consistent with “bottom-up” models of personality change (Hudson & Roberts, 2015; Roberts et al., 2008), in which engagement in new behaviors that bring reinforcement gradually lead to increases in the personality dispositions to engage in those new behaviors. There is a clear need for further development of models of personality change in general, as well as for models of maladaptive personality change in youth.

A different possibility is that early drinking produces brain alterations that result in personality change. Certainly there is good evidence that substantial consumption does alter aspects of brain functioning (Squeglia, Jacobus, & Tapert, 2009). However, the typical level of drinking in these youth was low enough that this possibility does not seem likely.

Although we controlled for two important predictors of personality change, there is an alternative explanation for the present findings. It may be the case that drinking change and personality change stem from a common cause in place prior to the onset of this longitudinal study. There may simply be a developmental process of maladaptive personality and behavior change that began before early adolescence and unfolds in a variety of ways over time, sometimes with drinking occurring before personality change, other times with personality change occurring before drinking. For example, genetic factors and early developmental vulnerabilities could provide a diathesis that leads to the emergence of all the factors we have described in some youth. The current data certainly do not rule out this possibility.

It is important to contextualize these findings within the limitations to this study. There are surely other possible predictors of urgency change, such as life stressors and other environmental events, which we did not model. Although there were relatively low attrition rates in this study and retained and lost participants did not differ on any study variables, we cannot know whether the results would have differed with even higher retention. All data were collected by questionnaire: although there is substantial evidence for the validity of all measures utilized in this study, questions and responses were not clarified as in an interview. Finally, there is a need to integrate the current findings into larger models that include other factors, such as parental and peer behavior and genetic risk to create a more comprehensive understanding of the evolution of risk and dysfunction in youth.

The current finding of reciprocal prediction between youth drinking and a maladaptive personality trait is important for both clinical theory and practice. With respect to theory, increased understanding of factors that lead to personality change enhances understanding of a core contributor to individual differences. Clinically, because the trait of urgency increases risk for multiple forms of dysfunction, youth drinking may serve as a marker for elevations in risk transdiagnostically. The need to intervene to reduce youth drinking may be even more important than currently understood, and the possibility of intervening in comprehensive way to reduce negative personality change merits exploration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge research support from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism as well as the National Institute on Drug Abuse with the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01 AA016166 to Gregory Smith and T32DA035200 Craig Rush. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

There appears to be a reciprocal relationship between the high-risk personality trait of urgency, the disposition to act rashly when emotional, and alcohol drinking behavior among young adolescents. Elevations in the trait predict increased drinking, and drinking behavior predicts increases in the trait. This process occurs in repeated cycles across the early adolescent years.

References

- Berg JM, Latzman RD, Bliwise NG, Lilienfeld SO. Parsing the Heterogeneity of Impulsivity: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Behavioral Implications of the UPPS for Psychopathology. 2015 doi: 10.1037/pas0000111. Online pre-publication, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pas0000111. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brown SA, McGue M, Maggs J, Schulenberg J, Hingson R, Swartzwelder S, Murphy S. A developmental perspective on alcohol and youths 16 to 20 years of age. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Supplement 4):S290–S310. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Smith GT, Donovan JE, Windle M, Faden VB, Chen CM, Martin CS. Drinking frequency as a brief screen for adolescent alcohol problems. Pediatrics. 2012:peds–2011. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman L, Coleman J. The measurement of puberty: a review. Journal of Adolescence. 2002;25:535–550. doi: 10.1006/jado.2002.0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskunpinar A, Dir AL, Cyders MA. Multidimensionality in impulsivity and alcohol Use: a meta- analysis using the UPPS model of impulsivity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37(9):1441–1450. doi: 10.1111/acer.12131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culbert KM, Burt SA, McGue M, Iacono WG, Klump KL. Puberty and the genetic diathesis of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:788–796. doi: 10.1037/a0017207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Flory K, Rainer S, Smith GT. The role of personality dispositions to risky behavior in predicting first year college drinking. Addiction. 2009;104(2):193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Mood-based rash action and its components: Positive and negative urgency. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43(4):839–850. [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134(6):807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Smith GT, Cyders MA. Another look at impulsivity: A meta-analytic review comparing specific dispositions to rash action in their relationship to bulimic symptoms. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(8):1413–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath LS, Milich R, Lynam D, Leukefeld C, Clayton R. Sensation Seeking and Substance Use: A Cross-Lagged Panel Design. Individual Differences Research. 2004;2(3):175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson NW, Roberts BW. Social investment in work reliably predicts change in conscientiousness and agreeableness: A direct replication and extension of Hudson, Roberts, and Lodi-Smith (2012). Journal of Research in Personality. 2015;60:12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Laurent J, Catanzaro SJ, Joiner TE, Jr, Rudolph KD, Potter KI, Lambert S, Gathright T. A measure of positive and negative affect for children: scale development and preliminary validation. Psychological Assessment. 1999;11(3):326–338. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ, Rubin DB. The analysis of social science data with missing values. Sociological Methods & Research. 1989;18(2-3):292–326. [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Vergés A, Wood PK, Sher KJ. Transactional models between personality and alcohol involvement: A further examination. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121(3):778–783. doi: 10.1037/a0026912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL, Almeida DM, Galambos NL. Risky business: The paradoxical meaning of problem behavior for young adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1995;15:344–362. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. User's guide. 3rd ed. Muthen & Muthen; Los Angeles, CA: 2004-2010. Mplus: The comprehensive modeling program for applied researchers. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism & American Academy of Pediatrics [June 4, 2015];Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention for Youth, A Practitioner's Guide. 2011 from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/YouthGuide/YouthGuide.pdf.

- Pearson CM, Combs JL, Zapolski TC, Smith GT. A longitudinal transactional risk model for early eating disorder onset. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121(3):707–718. doi: 10.1037/a0027567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1988;17:117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Work experiences and personality development in young adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84(3):582–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Kuncel NR, Shiner R, Caspi A, Goldberg LR. The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2007;2(4):313–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Walton K, Bogg T, Caspi A. De-investment in work and non- normative personality trait change in young adulthood. European Journal of Personality. 2006;20(6):461–474. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Wood D, Caspi A. The development of personality traits in adulthood. Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research. 2008;3:375–398. [Google Scholar]

- Settles RE, Zapolski TC, Smith GT. Longitudinal test of a developmental model of the transition to early drinking. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2014;123(1):141–151. doi: 10.1037/a0035670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Trull TJ. Personality and disinhibitory psychopathology: alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103(1):92–102. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Cyders MA. Integrating affect and impulsivity: The role of positive and negative urgency in substance use risk. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.038. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, McCarthy DM, Goldman MS. Self-reported drinking and alcohol-related problems among early adolescents: Dimensionality and validity over 24 months. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1995;56(4):383–394. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. Heightened stress responsivity and emotional reactivity during pubertal maturation: Implications for psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21(01):87–97. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squeglia LM, Jacobus J, Tapert SF. The influence of substance use on adolescent brain development. Clinical EEG and Neuroscience. 2009;40(1):31–38. doi: 10.1177/155005940904000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stautz K, Cooper A. Impulsivity-related personality traits and adolescent alcohol use: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33(4):574–592. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30(4):669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Smith GT. Personality and psychopathology. In: John O, Robins RW, Pervin L, editors. Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research. Third Edition Guilford; NY: 2008. pp. 743–769. [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TC, Stairs AM, Settles RF, Combs JL, Smith GT. The measurement of dispositions to rash action in children. Assessment. 2010;17(1):116–125. doi: 10.1177/1073191109351372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.