Abstract

Background:

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) is a new emerging zoonosis. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a life-threatening syndrome caused by hyperinflammation. Here, we report the case of SFTS-associated HLH.

Case summary:

A 62-year-old man was admitted to local hospital with 8 days of fever and chill. He had leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and developed seizure. An attending physician examined bone marrow to rule out hematologic malignancy. He was transferred to tertiary referral hospital for suspicious HLH. We decided to confirm its histologic feature for sure. Bone marrow and liver biopsy showed hemophagocyotic histiocytes. Serological tests for other infections were all negative except SFTS virus polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) as positive from serum, bone marrow, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and liver biopsy specimen. A definitive diagnosis was SFTS-associated HLH. During 2 weeks of conservative treatment, he succeeded in recovery from multiple organ failure.

Conclusion:

SFTS should be considered one of differential diagnosis of HLH. In certain endemic areas, SFTS infection deserves clinicians’ attention because it can be presented hematologic diseases as HLH.

Keywords: bunyavirus, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, histiocytosis, severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome

1. Introduction

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) is an emerging zoonosis.[1] It was first reported in China in 2011 and South Korea and Japan in 2013.[2,3] Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare but life-threatening clinical syndrome caused by extreme hyperinflammation. It is divided into primary and secondary triggered by viral infection, autoimmune disease, or a neoplasm. In adults, infections and drugs are the 2 main groups of causative agent.[4] Here, we describe a case of HLH associated with STFS virus infection and also provide a literature review.

2. Case report

A 62-year-old man, who had previously experienced 8 days of general weakness and feverishness with chilling, was admitted to local hospital A for generalized tonic clonic seizure-like movements. He had been working as a school security guard in a rural area. He only took medication for hypertension. The seizures terminated spontaneously within 1 minute, and his mentality was alert and oriented during interictal periods. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan and electroencephalography (EEG) findings were normal. His peak body temperature was 39.4 °C. The initial complete blood count revealed leukopenia and thrombocytopenia; white blood cell (WBC) count of 1900 × 106/L, platelet of 107,000 × 109/L, and hemoglobin of 13.4 g/dL. After administration of an antiepileptic (levetiracetam) and empirical piperacillin/tazobactam for any hidden bacterial infection, the frequency of seizures decreased, but the high fever was sustained. His bone marrow was examined 11 days after the onset of illness (hospital day [HD] 4), and features of hemophagocytosis were observed. His mentality gradually became confused with high-grade fever, and he suffered from dyspnea. Finally, he was intubated and transferred to a tertiary referral hospital for management of suspicious HLH.

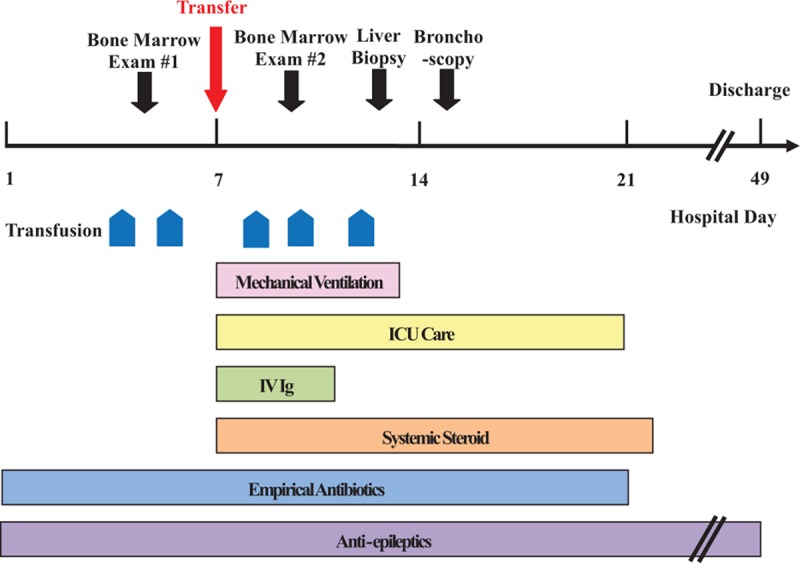

Fourteen days after the onset of illness (HD 7), he was admitted to hospital B (Fig. 1). His body temperature was 39.1 °C. Mental alertness could not be checked because of the administration of a sedative drug. There were no remarkable findings such as petechiae, hematochezia, lymphadenopathy, and conjunctival congestion on physical examination. The leukopenia was stationary (WBC count of 2400 × 106/L), but the thrombocytopenia had worsened (platelet of 49,000 × 109/L), and hemoglobin was 15.3 g/dL. Serum lactate dehydrogenase was 2745 IU/L, ferritin was 832 ng/mL, triglyceride was 627 mg/dL, Aspartate transaminase was 702 IU/L, Alanine transaminase was 155 IU/L, serum blood urea nitrogen was 15 mg/dL, serum creatinine was 1.24 mg/dL, and C-reactive protein was 0.3 mg/dL. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed no pleocytosis with mild elevation of protein; WBC count of 0, red blood cell (RBC) count of 0, protein of 90.1 mg/dL, glucose of 114 mg/dL, and no malignant cells. Chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed multifocal ground-glass opacities (GGOs) on both lungs. EEG showed severe diffuse cerebral dysfunction with low-amplitude activity.

Figure 1.

Timeline of interventions and outcomes.

Although the referral diagnosis was HLH, an attending doctor decided to confirm it and exclude other etiologies. Bone marrow examination and transjugular liver biopsy were performed. Serological tests for tuberculosis, Epstein–Barr virus, human immunodeficiency virus, scrub typhus, leptospirosis, and Hantaan virus hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome were performed. Bacterial cultures from respiratory specimen were also performed. In view of the emerging viral disease, molecular diagnostic tests for SFTS virus were included. Empirical antibiotics such as cefotaxime and doxycycline were given for hidden bacterial infections such as atypical pneumonia, including rickettsial diseases. Dexamethasone 20 mg/d and intravenous immunoglobulin (IV Ig) 500 mg/kg were also started for treatment of HLH. On 20 days after the onset of illness (HD 14), follow-up chest X-ray and CT scan showed increased patchy GGOs in both lungs and bilateral pleural effusion.

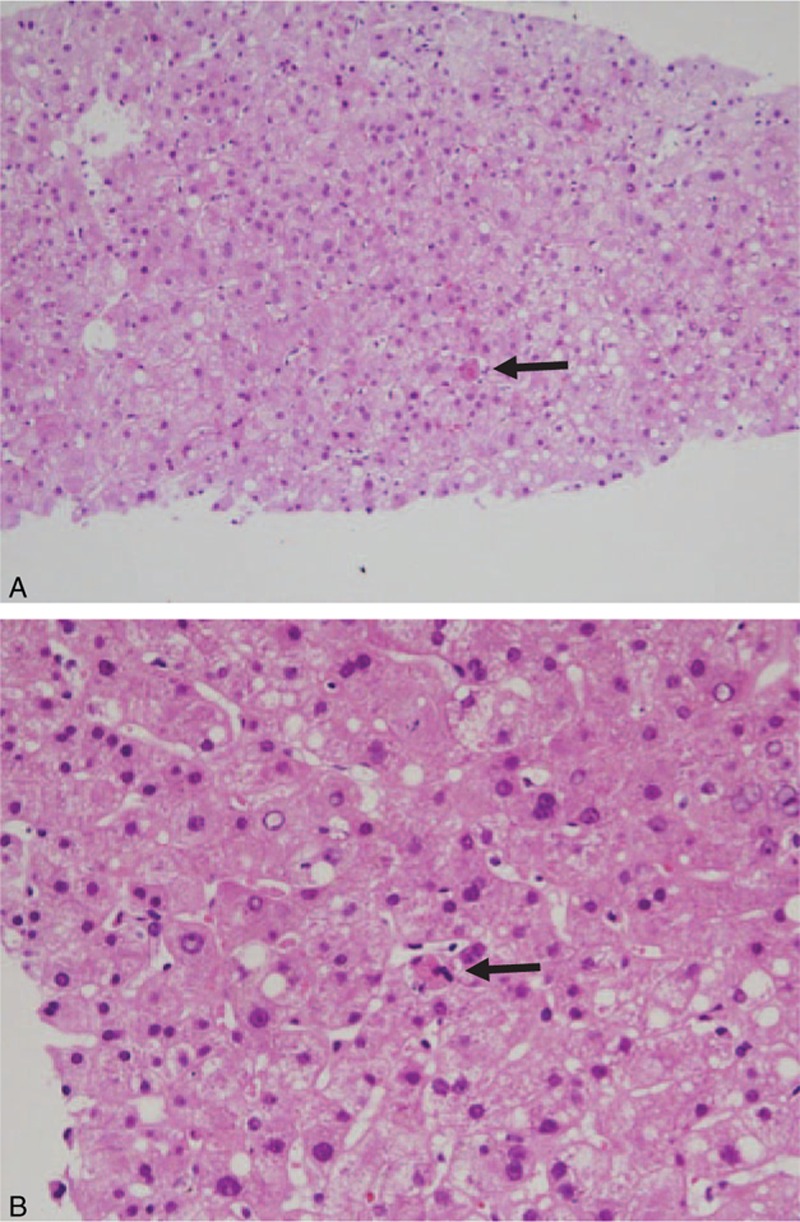

Bone marrow examination revealed hemophagocytic histiocytes. Examination of the liver biopsy specimen showed that the liver was mildly steatotic and there was mild lobular inflammation with a few acidophilic bodies in the lobular parenchyma (Fig. 2A). Higher power magnification revealed a few erythrophagocytic histiocytes in the sinusoids (Fig. 2B). There was no evidence of abnormal neoplastic cell infiltration in either the bone morrow or liver biopsy specimens. SFTS virus polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using serum, bone marrow, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid analysis, and liver biopsy specimens were positive. Other bacteriologic culture, serologic, and molecular tests for possible infectious causes gave negative findings or referred to past infections.

Figure 2.

(A) Liver biopsy showing mild steatosis and mild lobular inflammation with acidophilic bodies (arrow: original magnification ×100, hematoxylin-eosin stain). (B) A few erythrophagocytic histiocytes (arrow) can be seen in sinusoids (original magnification ×400, hematoxylin-eosin stain).

The patient was diagnosed with HLH associated with SFTS virus infection, and dexamethasone and IV Ig were continued. Because of suspicion of SFTS encephalitis with symptomatic seizure, the antiepileptic drug (levetiracetam) was given regularly. Over 2 weeks of conservative treatment with intravenous fluid, platelet transfusion, and mechanical ventilation, the patient succeeded in recovering from multiple organ failure. He could not recall any history of tick bite, and we could not find any tick bite wounds on physical examination. Since the patient had recovered from his illness after the use of steroid and IV Ig, cytotoxic chemotherapy for HLH was not administrated. After 6 months, follow-up brain MRI was normal and EEG showed improvement since the previous examination. His mental status was alert without any neurologic sequelae and he discontinued of antiepileptic drug. He was back to work as security guard.

3. Discussion

We have described a case of SFTS-associated HLH, confirmed using serum, bone marrow, and liver biopsy specimens. SFTS is an emerging tick-borne disease caused by the SFTS virus, a novel bunyavirus, which was first reported in China in 2011.[1] Korea and Japan reported SFTS-infected cases in 2013.[2,3] SFTS is characterized by high fever, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, diarrhea, vomiting, lymphadenopathy, multiple organ failure, and neurologic symptoms. The case-fatality rate of SFTS ranges from 12% to 30%.[1] SFTS is transmitted by tick bite and contact with body fluids of SFTS patients.[5] No specific treatment of SFTS has been established.

HLH is characterized by uncontrolled hypercytokinemia and organ infiltration by activated lymphocytes and histiocytes.[6] For the diagnosis of secondary HLH, in the absence of specific genetic defects and/or a familial history, 5 of the following 8 criteria are required: fever, splenomegaly, cytopenia affecting more than 2 cell lineages, hypertriglyceridemia and/or hypofibrinogenemia, hemophagocytosis in bone marrow, spleen, or lymph nodes without evidence of malignancy, decreased Natural killer-cell activity, hyperferritinemia, and elevated soluble Interleukin-2 receptor.[4] Our patient met 5 of these 8 criteria. We attempted to identify treatable infectious causes of HLH after ruling out malignant and autoimmune diseases. Because of the endemic nature of SFTS in South Korea, we were able to identify SFTS virus via the PCR positivity of serum, bone marrow, BAL fluid, and liver biopsy specimen. Cui et al[7] reported that 103 (19.1%) of 538 SFTS patients in China developed encephalitis. The altered mentality and seizure-like movements of our patient suggested that he might have SFTS encephalitis, but we were unable to verify this by brain MRI and CSF analysis. An SFTS PCR test of the CSF would have been helpful for diagnosing SFTS encephalitis, but unfortunately we did not perform the test at that time.

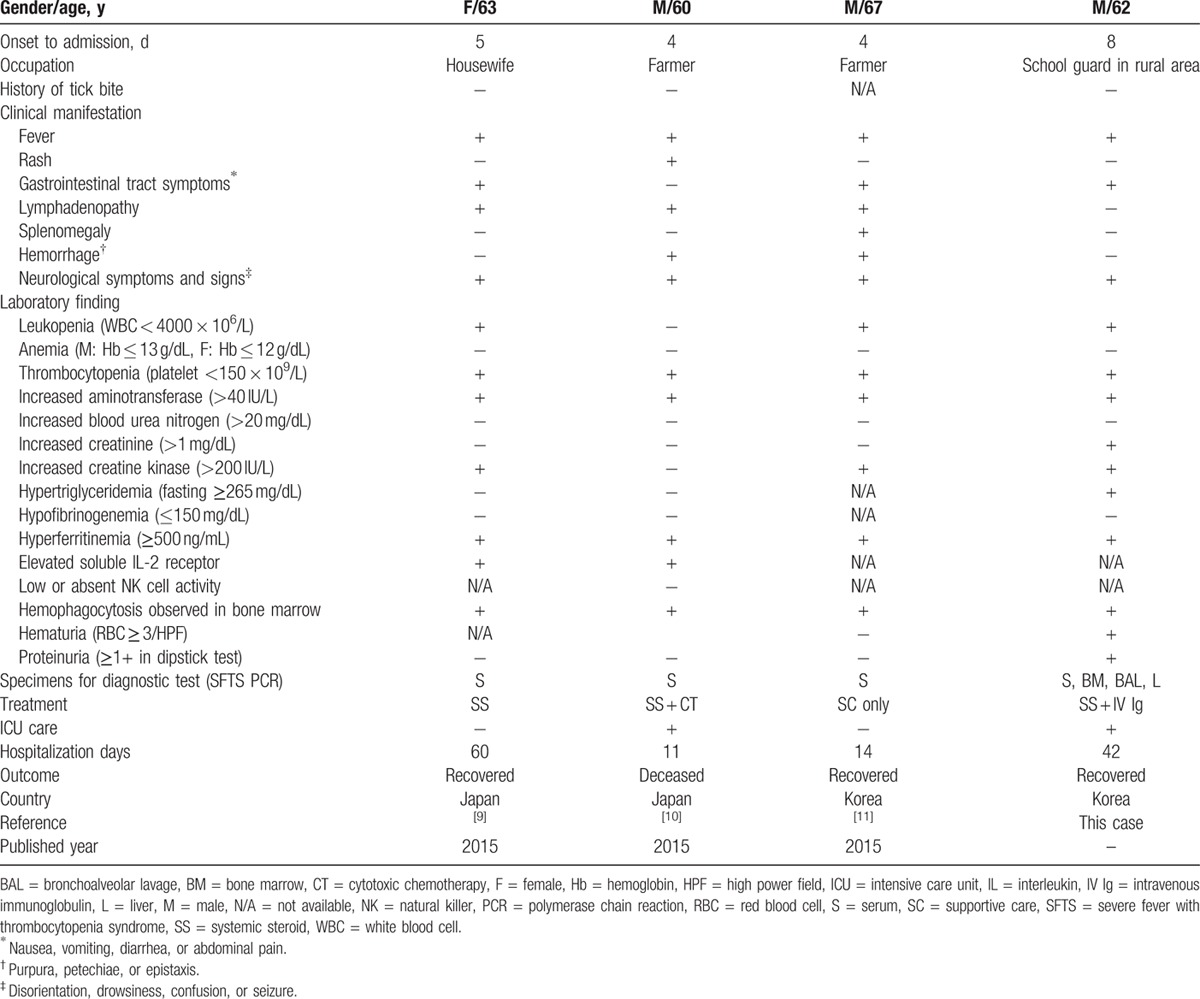

A few SFTS-associated HLH cases have been reported in the English and Japanese literature.[5,8–10] Weng et al[8] reported 5 cases associated with HLH among 12 SFTS patients, according to the diagnostic criteria for HLH issued by the American Society of Hematology in 2009; however, no detailed data are available. In Table 1, we summarize the clinical characteristics, laboratory results, and outcomes in all the other reports. Common findings in these reports are fever, thrombocytopenia, hyperferritinemia, and hemophagocytosis in bone marrow examinations. Azuma et al reported 1 SFTS case with HLH mimicking a lymphoid malignancy. They stated that differential diagnosis of intravascular lymphoma from SFTS infection is important in adult HLH. Kaneko et al reported a fatal SFTS case complicated by HLH. They found massive hemophagocytosis and immunohistochemical staining for SFTS virus in lymphoid tissues such as lymph nodes, liver, and spleen. Both the above cases were diagnosed as SFTS using remnant serum samples or autopsies examined retrospectively, not in the initial phase of hospitalization. Kim et al reported 1 HLH case among 3 SFTS patients. They conducted a retrospective observational study to evaluate the morphology of the bone marrow in the patients with confirmed SFTS. In contrast, since we suspected and tested for SFTS virus infection as one of the possible causes of HLH in the process of actual patient care, we were able to identify the cause of the HLH of our patient at an early stage. We were able to detect SFTS virus by PCR not only in the serum but also in a bone marrow examination, BAL fluid, and liver biopsy, and this might be a more rapid and practicable in actual clinical situations than immunohistochemical staining of tissue. Since we detected SFTS virus in BAL fluid by PCR for the first time, our case could be an evidence of pulmonary involvement with severe SFTS virus infection.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and laboratory results of reported SFTS-associated HLH cases.

In conclusion, the nonspecific laboratory findings and clinical manifestations make it difficult to suspect SFTS virus infection as the cause of HLH in the early stage of HLH.[11] However, HLH can be rapidly progressing and life-threatening if not adequately treated, and clinicians are always being challenged to investigate causative factors and start appropriate treatment simultaneously. Our case shows that SFTS virus infection should be considered as one of the predisposing diseases of HLH in endemic areas. Thus, clinicians need to be aware that SFTS virus infection can accompany hematologic diseases such as HLH.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Dr Masaki Yasukawa (Ehime University Graduate School of Medicine, Ehime, Japan), Dr Jongyoun Yi (Pusan National University Hospital, Pusan, South Korea), and Dr Yali Weng (Nanjing Medical University, Jiangsu, China) for sharing detailed information about patients. We also express our gratitude to Professor Julian D. Gross, University of Oxford, for English editing.

Patient consent: The patient provided written permission for publication of this case report.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BAL = bronchoalveolar lavage, CSF = cerebrospinal fluid, CT = computed tomography, EEG = electroencephalography, GGOs = ground-glass opacities, HD = hospital day, HLH = hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, ICU = intensive care unit, IV Ig = intravenous immunoglobulin, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, PCR = polymerase chain reaction, RBC = red blood cell, SFTS = severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, WBC = white blood cell.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Yu XJ, Liang MF, Zhang SY, et al. Fever with thrombocytopenia associated with a novel bunyavirus in China. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:1523–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim KH, Yi J, Kim G, et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, South Korea, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis 2013; 19:1892–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi T, Maeda K, Suzuki T, et al. The first identification and retrospective study of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in Japan. J Infect Dis 2014; 209:816–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zeron P, Lopez-Guillermo A, et al. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet 2014; 383:1503–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim WY, Choi W, Park SW, et al. Nosocomial transmission of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in Korea. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:1681–1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Risma K, Jordan MB. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: updates and evolving concepts. Curr Opin Pediatr 2012; 24:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cui N, Liu R, Lu QB, et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome bunyavirus-related human encephalitis. J Infect 2015; 70:52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weng Y, Chen N, Han Y, et al. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in Chinese patients. Braz J Infect Dis 2014; 18:88–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azuma T, Suemori K, Murakami Y, et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome mimicking intravascular lymphoma. Japan J Clin Hematol [Rinsho ketsueki] 2015; 56:491–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaneko M, Azuma T, Yasukawa M, et al. [A fatal case of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome complicated by hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis]. J Japan Assoc Infect Dis [Kansenshogaku zasshi] 2015; 89:592–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim N, Kim K-H, Lee SJ, et al. Bone marrow findings in severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome: prominent haemophagocytosis and its implication in haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Clin Pathol 2016; 69: 6 537–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]