Abstract

Rationale

Reentry underlies most ventricular tachycardias (VT) seen post-myocardial infarction (MI). Mapping studies reveal that the majority of VTs late post-MI arise from the infarct border-zone (IBZ).

Objective

To investigate reentry dynamics and the role of individual ion channels on reentry in in vitro models of the healed IBZ.

Methods and Results

We designed in vitro models of the healed IBZ by co-culturing skeletal myotubes (SkM) with neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) and performed optical mapping at high temporal and spatial resolution.

In culture, NRVMs mature to form striated myocytes and electrically uncoupled SkMs simulate fibrosis seen in the healed IBZ. High resolution mapping revealed that SkMs produced localized slowing of conduction velocity (CV), increased dispersion of CV and directional-dependence of activation delay without affecting myocyte excitability. Reentry was easily induced by rapid pacing in co-cultures; treatment with lidocaine, a Na+ channel blocker, significantly decreased reentry rate and CV, increased reentry pathlength and terminated 30% of reentrant arrhythmias (n=18). In contrast, nitrendipine, an L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC) blocker terminated 100% of reentry episodes while increasing reentry cycle length and pathlength and decreasing reentry CV (n=16). K+ channel blockers increased reentry APD, but infrequently terminated reentry (n=12).

Conclusions

Co-cultures reproduce several architectural and EP features of the healed IBZ. Reentry termination by LTCC, but not Na+ channel blockers suggests a greater Ca2+-dependence of propagation. These results may help explain the low efficacy of pure Na+ channel blockers in preventing and terminating clinical VTs late after MI.

Keywords: Arrhythmia, Ca2+ channels, Cardiac electrophysiology, Electrophysiology, Mapping, Na+ current, Optical mapping

Introduction

In the United States, myocardial infarction (MI) afflicts more than 7.1 million people with 865,000 new cases each year(3). Late after an MI, surviving myocyte bundles in the infarct, and the infarct border-zone (IBZ) have been implicated in the genesis of post-MI reentrant ventricular tachyarrhythmias(45) and sudden cardiac death. Currently, the treatment options for post-MI arrhythmias include defibrillator implantation combined with anti-arrhythmic drug therapy and/or ablation. Unfortunately, effective drug therapy for post-MI ventricular arrhythmias has been discouraging since they are pro-arrhythmic(24), lack efficacy(1, 6, 21, 51) and cause toxicity(36, 55). Understanding the role of ion channels on arrhythmia dynamics is crucial to developing tailored, new drug and gene-based therapies for ventricular tachy-arrhythmias. Currently, technical obstacles preclude three-dimensional mapping in whole heart studies, making 2-dimensional and theoretical models attractive options for studying the biophysics of reentrant arrhythmias.

Mapping studies have revealed that the majority of VTs originate from the infarct border-zone, a substrate that is characterized by non-uniform anisotropic architecture resulting from fibrosis that separates myocyte bundles and gap junction remodeling of surviving myocytes(52). Despite extensive ultra-structural and electrophysiological characterization of the healed IBZ, very little information exists regarding reentry dynamics and the role of individual ion channels on reentry. In this study, we adopted a reductionist, tissue engineering approach and created a new 2D in vitro model of the healed IBZ. We used optical mapping to characterize the substrate and study the effects of Na+, Ca2+ and K+ channel blockers on reentrant arrhythmia dynamics. We found that this 2D, co-culture model resembled the healed infarct border-zone in several architectural and electrophysiologic (EP) respects. An increased contribution of the L-type Ca2+ current to impulse propagation was observed in co-cultures (consisting of electrically uncoupled myotubes mixed with electrically coupled myocytes(40)), but not in myocyte-only controls. Low doses of nitrendipine (5µM), an L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC) blocker terminated 100% of reentrant arrhythmias, but high doses of lidocaine (200µM) only terminated 30% of reentry episodes in co-cultures(4). These results may help explain the low efficacy of pure Na+ channel blockers in terminating and preventing ventricular tachycardias that occur late after MI.

Materials and Methods

We investigated impulse propagation and arrhythmias by performing optical mapping of novel in vitro models of the healed epicardial(52) and lateral(32) infarct border-zones generated by co-culturing human skeletal myotubes (SkM) with neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs). We used skeletal myotubes to simulate fibrosis seen in the healed infarct border-zone because 1) they lack gap junctions unlike myofibroblasts that express connexin43 and connexin45(8, 20), 2) assume a linear morphology that resembles fibrosis seen in the healed IBZ10 and 3) orient neighboring myocytes into bundles, resulting in a non-uniform anisotropic architecture(34, 52), a cardinal feature of the healed IBZ.

The healed epicardial IBZ was simulated by plating a mixture of 20% SkMs with 80% NRVMs on 21mm fibronectin-coated plastic coverslips (Fig 1B and C), while a model of the healed lateral IBZ was created by micro-patterning a sector (θ=120°, 115mm2, Fig 5A) composed of a co-culture of (20–30%) SkMs and (70–80%) NRVMs adjacent to an NRVM-only region on fibronectin-coated polydimethyl siloxane-treated glass coverslips. Controls for this study consisted of NRVM-only monolayers. Optical mapping i.e. micromapping (20µm spatial and 125µs temporal resolution) and macromapping (1mm spatial and 1ms temporal resolution) were performed after 9–11 days in culture. Reentry was induced by rapid pacing; Na+, Ca2+ or K+ channel blockers were added to stable reentry (5 min after reentry initiation) and reentry dynamics were analyzed using custom software written in MATLAB.

Figure 1.

Panel A shows a transmitted light image of an NRVM-only control monolayer

Panels B and C shows a transmitted light and corresponding overlaid fluorescent microscopy image of a co-culture where myotubes are labeled with GFP. The myotubes are heterogeneously distributed; their orientation promotes neighboring NRVM alignment in several directions.

Panel D. Fluorescent image of a day 10 NRVM-only monolayer stained for α-Actinin (white) reveal striations resembling those observed in adult myocytes.

Panel E shows immunostaining for Cx43 (white) and nuclear labeling with Hoechst (blue) in a co-culture. Arrows point to areas of myotubes that have Hoechst-positive nuclei, but lack Cx43.

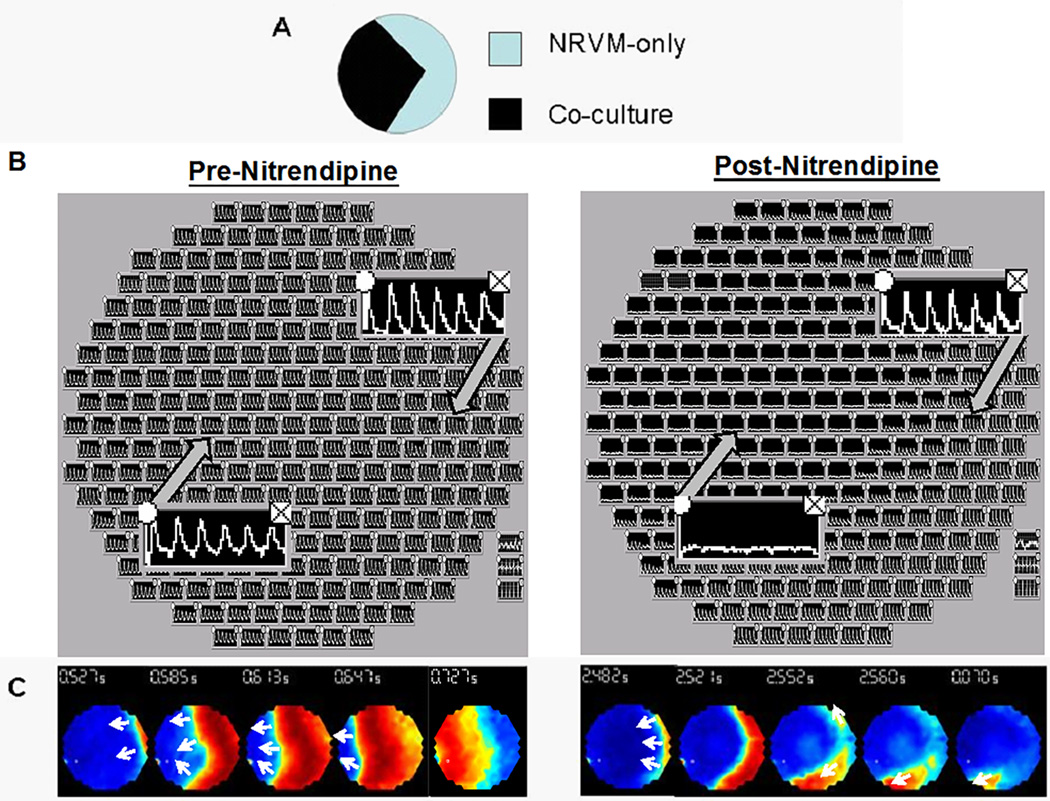

Figure 5. Sector (lateral) IBZ model exhibits Ca2+-dependent propagation.

Panel A is a schematic of the sector model.

Panels B and C show the tableau and voltage maps, respectively, during 2Hz stimulation (from the right) during normal tyrode (left) and nitrendipine (right) superfusion. During normal tyrode superfusion, all recording channels exhibit action potentials and voltage maps reveal slow conduction in the co-culture region. Nitrendipine superfusion produces conduction block of a planar wavefront at the interface of the co-culture and NRVM-only region.

A detailed description of the materials and methods is available in the online data supplement.

Results

Architectural Characterization

We studied NRVM-only controls (n=50) and co-cultures (n=50). Fig 1A shows a representative control, NRVM-only monolayer and Figs 1B and C show a representative transmitted light and corresponding fluorescent microscopy image of a co-culture where myotubes are labeled with GFP. In culture, NRVMs mature to form striated myocytes (Fig 1D) while myoblasts mature to form electrically uncoupled myotubes (100µM-2mm in length) that resemble ingrowths of fibrous tissue in the healed IBZ(34, 52) (Supplemental Fig 1). Furthermore, the myotubes orient bundles of myocytes in several directions (Fig 1B, C and Supplemental Fig 2), resulting in a non-uniform anisotropic structure which has been observed in the IBZ due to disarray of the usually parallel-oriented fiber bundles by fibrosis and lateralization of gap junctions (34, 52). Fig 1E shows Cx43 immunostaining of a co-culture that reveals lateralization of gap junctions in myocytes and lack of gap junctions in myotubes (arrows), both of which are normal features for these cell types. Additionally, impulse conduction in the epicardial border-zone is often confined to a 2D plane(14).

Electrophysiological Characterization

Electrophysiological studies in transplanted and intact human hearts as well as experimental models of healed myocardial infarctions reveal that the healed infarct border-zone is characterized by decreased conduction velocity (CV)(12, 52), increased dispersion of CV(12) and easily inducible, stable reentrant arrhythmias(15, 30, 33, 38), all of which are reproduced in this in vitro co-culture model.

Key EP features of the healed IBZ that are reproduced in this model are (1) reduction in CV(12, 52) at a macroscopic scale (Fig 2A), but normal myocyte excitability(52) (Fig 2B, C); (2) dispersion in CV at a microscopic scale(12) (Fig 2D, F, G) but negligible directional differences in impulse propagation at a macroscopic scale(52) (Fig 2H); (3) susceptibility to functional block (Fig 2I) and reentrant arrhythmias(15, 30, 33, 38) (Fig 2J, K) following rapid pacing. Remarkably, these features were observed in all co-cultures that were mapped (n=50 monolayers), but not in controls (Fig 2E).

Figure 2.

Panel A shows significantly decreased CV in co-cultures compared to NRVM-only controls.

Panel B shows representative optical upstroke traces from all 57 recording channels in a control and co-culture monolayer, using the micromapping setup

Panel C summarizes data from 5 controls and 6 co-cultures; dF/dtmax and hence excitability is similar in controls and co-cultures.

Panel D shows a transmitted light image superimposed on the fluorescent microscopy image of a co-culture. Stimulation on the right side produces a crowding of isochrones (spaced at an interval of 0.3ms apart) indicating slowing of conduction and circumvention of wavefronts in a region containing myotubes.

Panel E shows equally-spaced isochrones (spaced at an interval of 0.2ms apart) during transverse conduction in a control monolayer.

Panel F shows activation delay in co-cultures when stimulated from two different locations 2mm (radial distance) away from the field of view. Plotted are the upstrokes from all 57 recording sites of the array when stimulated from the right and bottom of the field of view.

Panel G shows a greater coefficient of variation in CV in co-cultures compared to NRVM-only controls.

Panel H shows uniform impulse propagation was observed at 3Hz pacing during macromapping.

Panel I shows development of localized conduction block during 4Hz pacing and a single spiral that developed at the end of the 4Hz pacing train (Panel J).

Panel K shows a representative pseudo-EKG of a single spiral wave exhibiting monomorphic VT before drug superfusion.

Panel L shows significantly increased APD in co-cultures compared to NRVM-only controls.

Optical mapping revealed that CV was decreased by 77% (Fig 2A; 5.7+/−1.1 vs. 24.4+/− 4.9 m/s, p<0.001) and APD was prolonged by 38% (Fig 2L; 143+/−29 vs. 197+/−39 ms, p<0.04) in co-cultures compared to controls on a macroscopic scale. This decrease in CV was primarily due to the underlying architecture, and not due to decreased excitability as demonstrated by similar upstroke velocities measured by micromapping (dF/dtmax = 0.33+/− 0.02 ms−1 vs. 0.34+/− 0.02 ms−1; p=0.33, n=7 each, controls and co-cultures respectively; Figs 2B, 2C) and similar resting membrane potential (−77mV in co-cultures vs. −74 mV in controls) by patch clamp in co-cultures and NRVM-only controls.

Myotubes oriented the NRVMs into bundles that resulted in rapid conduction when stimulated along the long axis of the bundles (Supplemental Fig 3A), but slower conduction when stimulated in the transverse direction (Supplemental Fig 3B). Additionally, presence of electrically uncoupled myotubes interposed between myocytes produced slowing of CV, but not complete block because of overlap between myotubes and myocytes. Fig 2D shows areas of widely spaced isochrones interspersed with significant slowing, evidenced by crowding of isochrones in a region containing myotubes (labeled with GFP), as well as circumvention of wavefronts around myotubes. In contrast, isochrones are uniformly spaced in all areas of control (NRVM-only) monolayers as seen in Fig 2E and Supplemental Fig 4 which show propagation along the transverse and longitudinal axis, respectively. Another interesting feature that has been reported in the healed IBZ is directional differences in activation delay, due to variable amounts and architecture of fibrosis that predispose to unidirectional block and reentry. Fig 2F illustrates this point: here, stimulation from the right resulted in a 20ms activation delay, while stimulation from the bottom resulted in an increase in the activation delay to 80ms due to large numbers of myotubes between the stimulation and recording sites. Paradoxically, propagation in co-cultures was uniform on a macroscopic scale following point stimulation at the center of the monolayer (Fig 2H) suggesting that as in the case of the healed IBZ, directional differences in propagation induced by myocyte bundles oriented in several directions on a microscopic scale canceled out.

Functional block and reentry can be readily induced in hearts with healed infarcts(15, 30, 33, 38) and in this in vitro model. In fact, reentrant arrhythmias could be initiated in all co-cultures by rapid pacing, and 90% of the reentrant arrhythmias sustained for >5 min, making them amenable to pharmacologic manipulation. Reentry initiation is illustrated in Figs 2 I and J; here uniform impulse propagation was observed at 3Hz pacing (Fig 2H), but localized conduction block was observed at 4Hz pacing (Fig 2I), culminating in sustained reentry (Fig 2J); pseudo EKGs of reentry resembled monomorphic VT (Fig 2K).

Effects of sodium and calcium channel blockade on spiral wave dynamics

Na+ channel blockers like lidocaine and agents like amiodarone that block Na+, Ca2+ and K+ channels are commonly used for the treatment and/or prevention of sustained ventricular tachycardia in patients with prior MI. We were interested in dissecting out the role of individual ion channels on spiral wave dynamics, so we utilized specific Na+, Ca2+ and K+ channel blockers, rather than amiodarone. In normal myocardium, lidocaine, exhibits use dependent Na+ channel blockade, slows CV and flattens CV restitution without affecting APD restitution(16), while nitrendipine, which produces use-dependent L-type Ca2+ channel blockade should flatten APD restitution but not significantly affect CV restitution(39).

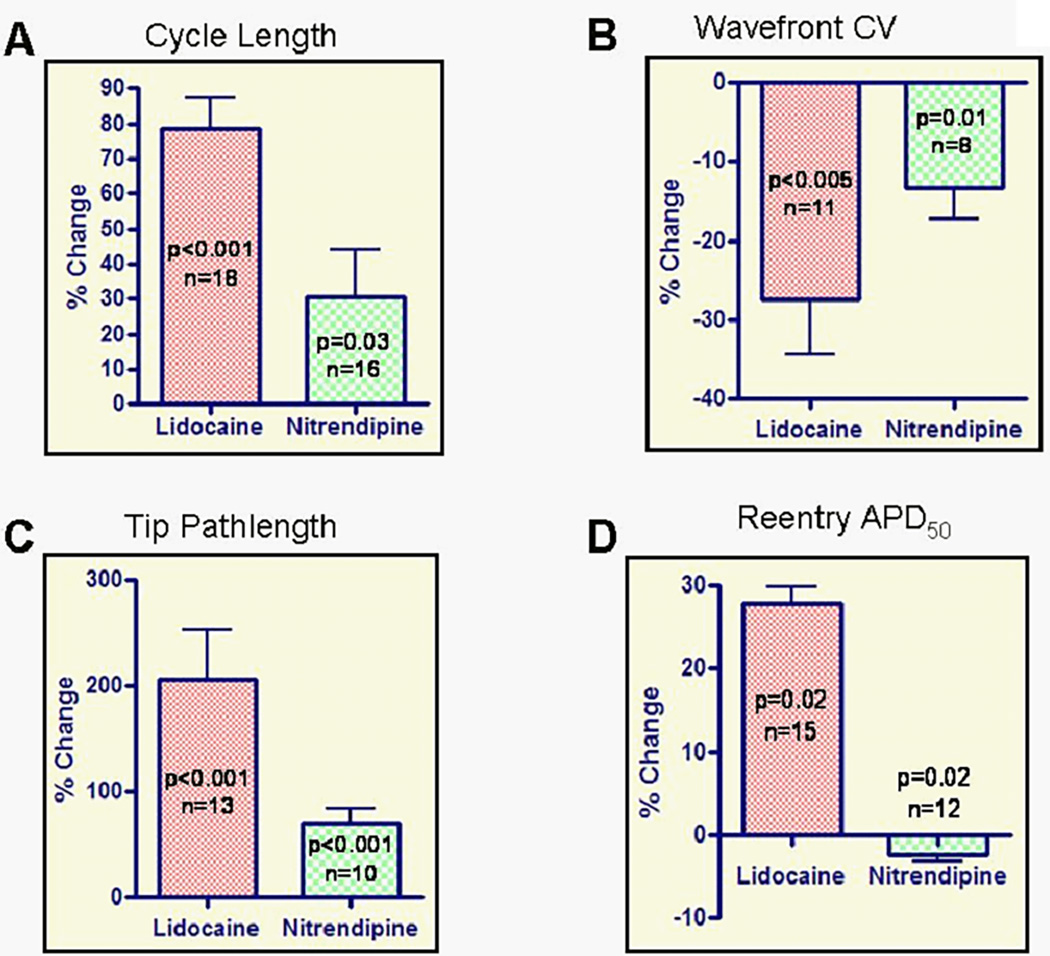

In this study, reentry cycle length (Figure 3A) was significantly increased by 79 +/− 38% (263+/− 25 vs. 446 +/− 29 ms, p<0.001, n=18 monolayers) and 30+/−14% (242+/−25 vs. 309+/−35 ms, p=0.03, n=16 monolayers) after perfusion with lidocaine (200µM) and nitrendipine (5µM), respectively. This increase in reentry cycle length was due to a decrease in reentry CV(-28+/−23%, 6.2+/−0.4 vs. 4.4+/−0.5 m/s, p<0.005, n=11; and -13+/−11%, 8.0+/−0.7 vs. 6.8+/−0.6 m/s, n=8, p=0.01; Fig 3B) and an increase in spiral core size, reflected by increase in the spiral tip pathlength by 207 +/− 160% (16.9+/−2.7 vs. 42.6+/−5.0 mm/cycle, p<0.001, n=13); and 71+/−42% (16.5+/−3.9 vs. 27.4+/−5.5 mm/cycle, p<0.001, n=10) for lidocaine and nitrendipine respectively (Fig 3C and Supplemental Fig 5). Additionally, lidocaine increased reentry APD50 by 28+/−8% (82+/−2 vs. 106+/−4 ms, p=0.02, n=15), whereas nitrendipine, produced a small decrease in APD50 (2% +/− 3%, 79+/−2 vs. 77+/−2 ms, p=0.02, n=12; Fig. 3D). The underlying mechanism of the observed changes in reentry APD is probably APD restitution(54, 58) where APD prolongs in response to an increase in cycle length. A modest prolongation of APD would be expected under lidocaine superfusion given (1) an insignificant change in the APD restitution relationship, and (2) a significant decrease in reentry rate. On the other hand, the small decrease in reentry APD with nitrendipine can be explained by a decrease in Ca2+ influx during the plateau phase of the APD due to LTCC blockade that is opposed (to a lesser extent) by the increase in reentry cycle length that tends to prolong APD.

Figure 3.

Reentry analysis was performed after > 8min of lidocaine superfusion and prior to reentry termination (~3min) during nitrendipine superfusion. Lidocaine significantly increased reentry cycle length (panel A), spiral tip pathlength (panel C), reentry APD50 (panel D), and significantly decreased reentry wavefront CV (panel B). Nitrendipine increased reentry cycle length, spiral tip pathlength, and decreased reentry wavefront CV and reentry APD50.

An unexpected finding was that reentry terminated after nitrendipine superfusion for 4–5 min, but only ~30% of reentry episodes were terminated by lidocaine despite superfusion for >10 min(4). Nitrendipine (Fig 4A), but not lidocaine (Fig 4B) induced wavebreaks prior to reentry termination. These results were confirmed by power spectrum analysis(57), which revealed an additional peak following nitrendipine (Figs 4D and 4E) suggesting wavebreak, whereas a single dominant frequency was seen during lidocaine superfusion (Fig 4C). Also, optical recordings revealed 2:1 block (resembling graded response(27)) at the recording site corresponding to the wavebreak (Fig 4F), whereas recording sites distant to the wavebreak demonstrated 1:1 capture (Fig 4G).

Figure 4.

Panel A shows a representative experiment that illustrates the effects of nitrendipine on reentrant arrhythmias: wavebreaks (white arrow) occur during sustained clockwise-rotating reentry after 4 min of perfusion and precede reentry termination.

Panel B shows a representative sustained reentry (clockwise-rotating) during lidocaine superfusion; no wavebreaks occur.

Panels C and D shows overlaid power spectra of all 253 recording channels during lidocaine and nitrendipine superfusion, respectively. A distinct dominant frequency during lidocaine perfusion (Panel C) confirms that no wavebreaks occur throughout the monolayer. During nitrendipine superfusion (Panel D), a frequency component lower than the dominant frequency of reentry (white arrow) represents the occurrence of wavebreaks in the monolayer.

Panel E shows single-channel power spectra of reentry during nitrendipine superfusion in a region where wavebreak occurs (left) and where wavebreak does not occur (right). Values plotted are normalized to the peak power across all channels.

Panels F and G show optical recordings, during nitrendipine superfusion, from the recording site corresponding to (2:1 block exhibiting graded response) and distant to (1:1 capture) wave break occurrence, respectively.

Potassium channel blockade does not terminate reentry

Potassium channel blockers like sotalol are often used to prevent ventricular tachy-arrhythmias in conjunction with ICD therapy. We evaluated d-sotalol (300µM), an IKr blocker and tetraethylammonium (TEA) (20mM), a non-specific K+ channel blocker. These agents prolonged reentry APD (Supplemental Fig 6A; p<0.005) by 7.6 ± 1.9 % during d-sotalol and 3.8 ± 0.8 % during TEA superfusion but did not affect reentry CL or induce wavebreaks (Supplemental Fig 6B); d-sotalol did not terminate reentry (n=6), whereas TEA terminated 1/6 reentry, an effect probably stemming from insufficient reentry APD prolongation.

Calcium-dependent propagation

Next, we investigated impulse propagation and arrhythmias in the sector model that simulates the lateral IBZ (n=7 monolayers; Fig 5A). The co-culture region demonstrated slow propagation (CV was decreased by 54 ± 7% (p<0.01)) relative to the control region during normal tyrode perfusion, and conduction block developed in the co-culture region within 5min of nitrendipine superfusion (Figs 5B, C).

Spiral waves with transient concave wavefront

A novel finding observed in these patterned cultures was the induction of stable, spiral waves with transient concave wavefronts, following rapid pacing. This is illustrated in Fig 6B and Supplemental Movie, where the spiral wave propagates in the counterclockwise direction. Fig 6 A1–A5 shows the voltage maps following the 5 point stimuli delivered just prior to induction of these spiral waves.

Figure 6. Spiral waves with transient concave wavefront in the sector model were initiated by 3Hz pacing.

Panel A1-A5 shows voltage maps following the 1st-5th delivered point stimuli, respectively, prior to induction of spiral waves with transient concave wavefront.

Panel A1 shows propagation through the entire monolayer;

Panels A2 and A3 show conduction block at 7 o’clock;

Panel A4 shows conduction block at the 7 and 11 o’clock with excitation extinguishing in the center;

Panel A5 shows conduction block at 7 o’clock while the upper arm at 11 o’clock continued to propagate, facilitating the initiation of a spiral waves with transient concave wavefront.

Panel B shows a spiral wave with transient concave wavefront rotating in the counterclockwise direction.

Discussion

In this study, we designed an in vitro model that reproduces several architectural and electrophysiologic features of the healed infarct border-zone (Table 1). We demonstrated that this model exhibits readily inducible reentrant arrhythmias that are consistently terminated by nitrendipine, an L-type Ca2+ channel blocker, but not high doses of lidocaine, a Na+ channel blocker or K+ channel blockers, suggesting increased contribution of the L-type Ca2+ current to impulse propagation due to decreased cell-cell coupling. These results may help explain the low efficacy of Na+ channel blockers like lidocaine in terminating sustained ventricular tachycardia in patients with old myocardial infarcts; significantly, these clinical arrhythmias are often terminated by intravenous amiodarone, which when administered acutely, produces use-dependent Na+ and Ca2+ channel blockade, without an appreciable effect on cardiac repolarization(31).

Table 1.

Architectural and electrophysiological similarities between SkM-NRVM co-cultures and the healed IBZ.

| Characteristics of the Healed Infarct Border Zone |

SkM-NRVM Co-culture IBZs | |

|---|---|---|

| A | In transmural infarcts, the infarct border zone (IBZ) is often a thin sheet epicardial or endocardial tissue with impulse conduction confined to an essentially 2D plane(14). Interstitial space accounts for approximately 15 to 22% of the total sectional area of border zone samples compared to 6% in normal myocardium(34) |

Inexcitable and electrically uncoupled Skeletal myotubes represent 10% to 20% of the 2D monolayer (Fig 1B, C, E, and Supplemental Fig 2). |

| B | Myocardial fibers, oriented in multiple directions combined with lateralization of gap junctions results in a non-uniformly anisotropic structure(34, 52). | Skeletal myotubes produce a non-uniformly anisotropic structure with myocytes groups oriented in multiple directions (Fig 1B, C, and Supplemental Fig 2). NRMVs demonstrate lateralization of gap junctions (Fig 1E). |

| C | Ingrowths of fibrous tissue(34) contribute to decrease in cell-cell coupling. | Interdigitating uncoupled myotubes. |

| D | Microelectrode recordings of resting membrane potential and upstroke velocities were observed to be normal(52) | Resting membrane potentials (co-culture vs. controls: −77mV vs. −74mV; n = 1 control and 2 co-cultures) and upstroke velocities by micromapping were similar in co-cultures and controls (co-cultures vs. controls: 0.33+/− 0.02 ms−1 vs. 0.34+/− 0.02 ms−1; p=0.33, n=7; Fig 2B and C). |

| E | Decreased conduction velocity (CV) and dispersion of CV at a microscopic scale(12, 52) | Significant reduction of macroscopic CV (Fig 2A) in co-cultures and marked dispersion of CV on a microscopic scale (Fig 2D) when compared with control NRVM-only monolayers (Fig 2E). |

| F | Prolongation of APD in cells from the border-zone(12, 52) | APD in co-cultures are prolonged compared with controls (Fig 2L; 143+/−29 vs. 197+/−39 ms, p<0.04). |

| G | Negligible directional differences in impulse propagation at a macroscopic scale12 | Negligible directional differences in impulse propagation at a macroscopic scale (Fig 2G and H) despite significant dispersion of CV on a microscopic scale in co-cultures. |

| H | Highly susceptible to reentrant arrhythmias and functional block(15, 30, 33, 38) | Functional block at high pacing rates culminating in stable reentrant arrhythmias (Fig 2I and J), the in vitro equivalent of monomorphic VT (Fig 2K) was seen only in co-cultures. |

| I | Direction-dependent propagation delay on a microscopic scale(9, 11) | Micromapping revealed direction dependent propagation delay (Fig 2F) in co-cultures but not controls. |

Effects of L-type Ca2+channel blockade in co-cultures

Impulse propagation in the heart is dependent on active membrane properties determined by the ion channel composition, and passive properties determined by architecture, cell size, gap junction function and distribution(48). In this model as well as in the healed infarct border-zone, architecture plays an important role in impulse propagation and arrhythmogenesis. Using microelectrode recordings, Ursell et al.(52) demonstrated that surviving myocytes in the healed IBZ have normal resting membrane potentials and normal action potential morphologies. However, CV is significantly reduced in these regions due to a combination of distortion of myocyte alignment, interstitial fibrosis and gap junction remodeling. This slow, heterogeneous electrical propagation can be located epicardially, endocardially and/or laterally and produces low voltage, complex, fractionated electrograms(19) that are used clinically to identify ablation sites in patients with ventricular arrhythmias(7, 49, 50).

Important insights into arrhythmia mechanisms can be gained by study of impulse propagation and arrhythmia dynamics. However, study of impulse propagation and arrhythmia dynamics in the whole heart is technically challenging, dictating use of reductionist approaches like theoretical and 2D in vitro models. Using a theoretical model, Shaw et al(46) demonstrated that as cell-cell coupling decreases, the contribution of the L-type Ca2+ current to action potential propagation increases, while that of the Na+ current decreases. In this co-culture model, we demonstrate that myocyte excitability is normal but overall cell-cell coupling is reduced due to the presence of electrically uncoupled skeletal myotubes interposed between the myoctes. The myotubes also align myocytes into bundles oriented in several directions (Supplemental Fig 2) producing a non-uniform anisotropic architecture that contributes to the EP phenotype. Our micromapping results indicate that on a microscopic scale, impulse propagation is rapid parallel to myocyte fiber direction (Supplemental Fig 4), but slows significantly when it comes across interposed myotubes (Fig 2D and Supplemental Fig 7), producing activation delays and contributing to decrease in macroscopic CV; similar zig-zag activation was observed by Rohr et al.(43) in cell strands treated with gap junction uncouplers, and in studies on the healed IBZ(11, 12). This decreased cell-cell coupling would increase intercellular delays and increase dependence of propagation on the L-type Ca2+ current; this would explain the conduction block observed in the co-culture region of the micro-patterned sector model following nitrendipine superfusion, and termination of stable reentry with nitrendipine, but not lidocaine.

Reentry initiation with rapid pacing

Clinical and experimental data support reentry as the most common cause of ventricular arrhythmias in healed infarcts. Reentry can be classified into anatomical or functional; mitral isthmus-dependent VT after inferior MI is an example of anatomical reentry(18, 23): here, the impulse circulates around an anatomical obstacle, the scar.

Functional reentry on the other hand, can be induced even in homogeneous tissues, take the form of spirals and has also been observed in ex vivo whole heart preparations(41). Functional block is essential for reentry initiation; a short wavelength (product of CV and refractory period) favors maintenance of both anatomical and functional reentry by decreasing the size of tissue needed to sustain reentry. Decreased cell-cell coupling combined with non-uniform anisotropic architecture significantly decreases CV(47), thereby decreasing wavelength and thus increasing the likelihood that a reentry circuit or spiral wave would be contained within the IBZ of healed infarcts or a 21mm coverslip. Rapid pacing or premature stimuli would amplify dispersions in CV and activation times, predisposing to functional block and reentrant arrhythmias. Additionally, heterogeneities would also promote anchoring of spiral waves(37) and an EKG pattern of monomorphic VT (Fig 2K). Our experiments reveal that functional block produces wavebreaks that precede reentry initiation (Figs 2I and J). We hypothesize that electrically uncoupled myotubes or fibrous tissue ingrowths combined with non-uniform anisotropic architecture predispose to areas of source-load mismatch that block at high pacing rates or following premature beats(11, 13), resulting in reentry initiation. Slow CV caused by decreased cell-cell coupling also increases the safety factor of propagation(22, 42, 46) which would promote sustained reentrant arrhythmias.

Mechanisms underlying reentry termination

Reentry termination can occur due to detachment of the wave from an obstacle, increase in reentry APD that promotes head-tail collision or interruption of the reentry circuit. The limited length of optical recordings (2–4 sec) did not allow us to capture the termination of reentry. We hypothesize that the mechanism of reentry termination with nitrendipine, an L-type Ca2+ channel blocker was decreased safety factor for propagation and conduction block in multiple areas of the monolayer; these conduction blocks would decrease the size of excitable medium available for reentry and consequently terminate reentry. This hypothesis was bolstered by our observation of conduction block in large areas of the monolayer after the termination of reentry. Similar results are illustrated in Fig 5C which demonstrates conduction block only in the co-culture region of the sector following nitrendipine superfusion.

We speculate that LTCC-mediated conduction block in reentry circuits may help explain clinical studies where Ca2+ channel blockers have been observed to reduce mortality in patients without significant left ventricular dysfunction(2, 26), conditions where the negative inotropic effects of Ca2+ blockers may not be detrimental. Furthermore, our findings may also explain our clinical experience where patients with sustained VT and old infarcts often respond to intravenous amiodarone (which mainly inhibits the depolarization phase of action potentials by use-dependent Ca+2 and Na+ channel blockade), but not lidocaine a relatively pure Na+ channel blocker. In the 3D heart, where an increased number of shunt pathways are available for impulse propagation, pure Ca2+ channel blockers may not be effective(25), and a combination of LTCC and Na+ channel blockade(5) may be necessary to terminate or prevent reentrant arrhythmias late after myocardial infarction.

Mechanism underlying spiral waves with transient concave wavefront

We have demonstrated for the first time the presence of spiral waves with transient concave wavefront in biological tissue. This phenomenon has been observed in experimental and computational studies of chemical reactions(35, 53), as well as in the FitzHugh-Nagumo (FHN) computational model(10) by imposing inhomogeneous excitability with specific geometric features.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations. NRVMs used in the study are electrophysiologically different from adult cardiac myocytes(17). Nevertheless, previous studies using patch clamp have demonstrated that the biophysical properties of LTCCs in neonatal and adult rat ventricular myocytes are similar(28), although Na+ channel blockade by lidocaine was more pronounced in NRVMs when compared to adult myocytes(56). Hypertrophy and ion channel remodeling(29, 44) that occurs in the IBZ is not completely replicated in this in vitro model; despite this drawback, we were still able to reproduce important structural and electrophysiological features of the healed IBZ. Photobleaching of di-4-ANEPPS limited our ability to obtain long-term voltage recordings, resulting in our inability to capture termination of reentry during nitrendipine treatment; hence we had to rely on the last recording (<2 min) prior to reentry termination for spiral wave analysis. Consequently, the actual changes in specific reentry parameters under maximum Ca2+ channel blockade could be larger than those presented in this study. The macromapping system used in this study is a contact fluorescence imaging system that precludes assessment of architecture concurrently with optical mapping. Lastly, we minimized, but were unable to fully eliminate fibroblasts in our cultures by 2 pre-plating steps. While fibroblasts may affect the electrophysiologic properties of cultures, we assume that they are present to a similar extent in co-cultures and controls and hence would not affect the validity of our results.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that a mixture of skeletal myotubes and NRVMs forms a substrate that reproduces several architectural and electrophysiologic features of the healed infarct border-zone. All reentrant arrhythmias in this model were terminated by LTCC blockade, whereas only ~30% were terminated by Na+ channel blockade(4). This study highlights the differential effects of Na+ and Ca+2 channel blockers in an in vitro model of the healed IBZ and may help explain the low efficacy of lidocaine in the treatment of incessant VT episodes in patients with healed infarcts. Furthermore, we have shown for the first time the presence of spiral waves with transient concave wavefront in cardiac tissue, suggesting that this novel arrhythmia phenotype may exist in the in vivo setting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Rachel R. Smith for graciously providing pathology slides of the in vivo healed infarct borderzone.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by the Scientist Development Grant from the AHA (M.R.A.), Donald W. Reynolds Foundation, National Institutes of Health Grant HL66239 (L.T.), and NIH MSTP T32GM008042.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Ca2+

calcium

- CV

conduction velocity

- EP

electrophysiologic

- FHN

FitzHugh-Nagumo

- IBZ

infarct border-zone

- LTCC

L-type Ca2+ channel

- MI

myocardial infarction

- NRVMs

neonatal rat ventricular myocytes

- SkM

skeletal myotubes

- Na+

sodium

- TEA

tetraethylammonium

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Effect of the antiarrhythmic agent moricizine on survival after myocardial infarction. The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial II Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:227–233. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199207233270403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Effect of verapamil on mortality and major events after acute myocardial infarction (the Danish Verapamil Infarction Trial II--DAVIT II) Am J Cardiol. 1990;66:779–785. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90351-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics -- 2005 Update Dallas. Texas: American Heart Assocation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abraham MR, Henrikson CA, Tung L, Chang MG, Aon M, Xue T, Li RA, B OR, Marban E. Antiarrhythmic engineering of skeletal myoblasts for cardiac transplantation. Circ Res. 2005;97:159–167. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000174794.22491.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adamson PB, Vanoli E, Shibano T, Foreman RD, Schwartz PJ. Combined sodium and calcium channel blockade in prevention of lethal arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2003;41:665–670. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200305000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aronow WS, Mercando AD, Epstein S, Kronzon I. Effect of quinidine or procainamide versus no antiarrhythmic drug on sudden cardiac death, total cardiac death, and total death in elderly patients with heart disease and complex ventricular arrhythmias. Am J Cardiol. 1990;66:423–428. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90697-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callans DJ, Ren JF, Michele J, Marchlinski FE, Dillon SM. Electroanatomic left ventricular mapping in the porcine model of healed anterior myocardial infarction. Correlation with intracardiac echocardiography and pathological analysis. Circulation. 1999;100:1744–1750. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.16.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chilton L, Giles WR, Smith GL. Evidence of intercellular coupling between co-cultured adult rabbit ventricular myocytes and myofibroblasts. The Journal of physiology. 2007;583:225–236. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.135038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciaccio EJ. Premature excitation and onset of reentrant ventricular tachycardia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H1703–H1712. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00310.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidsen J, Glass L, Kapral R. Topological constraints on spiral wave dynamics in spherical geometries with inhomogeneous excitability. Physical review. 2004;70:056203. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.70.056203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Bakker JM, Coronel R, Tasseron S, Wilde AA, Opthof T, Janse MJ, van Capelle FJ, Becker AE, Jambroes G. Ventricular tachycardia in the infarcted, Langendorff-perfused human heart: role of the arrangement of surviving cardiac fibers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:1594–1607. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)92832-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Bakker JM, van Capelle FJ, Janse MJ, Tasseron S, Vermeulen JT, de Jonge N, Lahpor JR. Slow conduction in the infarcted human heart. 'Zigzag' course of activation. Circulation. 1993;88:915–926. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.3.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Bakker JM, van Capelle FJ, Janse MJ, Wilde AA, Coronel R, Becker AE, Dingemans KP, van Hemel NM, Hauer RN. Reentry as a cause of ventricular tachycardia in patients with chronic ischemic heart disease: electrophysiologic and anatomic correlation. Circulation. 1988;77:589–606. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.77.3.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dillon SM, Allessie MA, Ursell PC, Wit AL. Influences of anisotropic tissue structure on reentrant circuits in the epicardial border zone of subacute canine infarcts. Circ Res. 1988;63:182–206. doi: 10.1161/01.res.63.1.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Downar E, Kimber S, Harris L, Mickleborough L, Sevaptsidis E, Masse S, Chen TC, Genga A. Endocardial mapping of ventricular tachycardia in the intact human heart. II. Evidence for multiuse reentry in a functional sheet of surviving myocardium. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1992;20:869–878. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90187-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fei H, Yazmajian D, Hanna MS, Frame LH. Termination of reentry by lidocaine in the tricuspid ring in vitro. Role of cycle-length oscillation, fast use-dependent kinetics, and fixed block. Circ Res. 1997;80:242–252. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fermini B, Schanne OF. Determinants of action potential duration in neonatal rat ventricle cells. Cardiovasc Res. 1991;25:235–243. doi: 10.1093/cvr/25.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman PA, Packer DL, Hammill SC. Catheter ablation of mitral isthmus ventricular tachycardia using electroanatomically guided linear lesions. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2000;11:466–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2000.tb00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardner PI, Ursell PC, Fenoglio JJ, Jr, Wit AL. Electrophysiologic and anatomic basis for fractionated electrograms recorded from healed myocardial infarcts. Circulation. 1985;72:596–611. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.72.3.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaudesius G, Miragoli M, Thomas SP, Rohr S. Coupling of cardiac electrical activity over extended distances by fibroblasts of cardiac origin. Circ Res. 2003;93:421–428. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000089258.40661.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gottlieb SH, Achuff SC, Mellits ED, Gerstenblith G, Baughman KL, Becker L, Chandra NC, Henley S, Humphries JO, Heck C, et al. Prophylactic antiarrhythmic therapy of high-risk survivors of myocardial infarction: lower mortality at 1 month but not at 1 year. Circulation. 1987;75:792–799. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.4.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gutstein DE, Morley GE, Tamaddon H, Vaidya D, Schneider MD, Chen J, Chien KR, Stuhlmann H, Fishman GI. Conduction slowing and sudden arrhythmic death in mice with cardiac-restricted inactivation of connexin43. Circ Res. 2001;88:333–339. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hadjis TA, Stevenson WG, Harada T, Friedman PL, Sager P, Saxon LA. Preferential locations for critical reentry circuit sites causing ventricular tachycardia after inferior wall myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1997;8:363–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1997.tb00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haverkamp W, Wichter T, Chen X, Hordt M, Willems S, Rotman B, Hindricks G, Kottkamp H, Borggrefe M, Breithardt G. The pro-arrhythmic effects of anti-arrhythmia agents. Zeitschrift fur Kardiologie. 1994;83(Suppl 5):75–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishikawa K, Nakai S, Takenaka T, Kanamasa K, Hama J, Ogawa I, Yamamoto T, Oyaizu M, Kimura A, Yamamoto K, Yabushita H, Katori R. Short-acting nifedipine and diltiazem do not reduce the incidence of cardiac events in patients with healed myocardial infarction. Secondary Prevention Group. Circulation. 1997;95:2368–2373. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.10.2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jespersen CM. The effect of verapamil on major events in patients with impaired cardiac function recovering from acute myocardial infarction. The Danish Study Group on Verapamil in Myocardial Infarction. European heart journal. 1993;14:540–545. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/14.4.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kao CY, Hoffman BF. Graded and decremental response in heart muscle fibers. The American journal of physiology. 1958;194:187–196. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1958.194.1.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katsube Y, Yokoshiki H, Nguyen L, Yamamoto M, Sperelakis N. L-type Ca2+ currents in ventricular myocytes from neonatal and adult rats. Canadian journal of physiology and pharmacology. 1998;76:873–881. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-76-9-873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim YK, Kim SJ, Kramer CM, Yatani A, Takagi G, Mankad S, Szigeti GP, Singh D, Bishop SP, Shannon RP, Vatner DE, Vatner SF. Altered excitation-contraction coupling in myocytes from remodeled myocardium after chronic myocardial infarction. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2002;34:63–73. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kleber AG, Fast VG, Kucera J, Rohr S. Physiology and pathophysiology of cardiac impulse conduction. Z Kardiol. 1996;85(Suppl 6):25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kodama I, Kamiya K, Toyama J. Cellular electropharmacology of amiodarone. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;35:13–29. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koyanagi S, Eastham CL, Harrison DG, Marcus ML. Transmural variation in the relationship between myocardial infarct size and risk area. Am J Physiol. 1982;242:H867–H874. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1982.242.5.H867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Littmann L, Svenson RH, Gallagher JJ, Selle JG, Zimmern SH, Fedor JM, Colavita PG. Functional role of the epicardium in postinfarction ventricular tachycardia. Observations derived from computerized epicardial activation mapping, entrainment, and epicardial laser photoablation. Circulation. 1991;83:1577–1591. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.5.1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luke RA, Saffitz JE. Remodeling of ventricular conduction pathways in healed canine infarct border zones. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1991;87:1594–1602. doi: 10.1172/JCI115173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Magnani A, Marchettini N, Ristori S, Rossi C, Rossi F, Rustici M, Spalla O, Tiezzi E. Chemical waves and pattern formation in the 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine/water lamellar system. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126:11406–11407. doi: 10.1021/ja047030c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morady F, Sauve MJ, Malone P, Shen EN, Schwartz AB, Bhandari A, Keung E, Sung RJ, Scheinman MM. Long-term efficacy and toxicity of high-dose amiodarone therapy for ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 1983;52:975–979. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(83)90515-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pertsov AM, Davidenko JM, Salomonsz R, Baxter WT, Jalife J. Spiral waves of excitation underlie reentrant activity in isolated cardiac muscle. Circ Res. 1993;72:631–650. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pogwizd SM, Hoyt RH, Saffitz JE, Corr PB, Cox JL, Cain ME. Reentrant and focal mechanisms underlying ventricular tachycardia in the human heart. Circulation. 1992;86:1872–1887. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.6.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qu Z, Weiss JN, Garfinkel A. Cardiac electrical restitution properties and stability of reentrant spiral waves: a simulation study. The American journal of physiology. 1999;276:H269–H283. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.1.H269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reinecke H, MacDonald GH, Hauschka SD, Murry CE. Electromechanical coupling between skeletal and cardiac muscle. Implications for infarct repair. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:731–740. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.3.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ripplinger CM, Krinsky VI, Nikolski VP, Efimov IR. Mechanisms of unpinning and termination of ventricular tachycardia. American journal of physiology. 2006;291:H184–H192. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01300.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rohr S, Kucera JP, Fast VG, Kleber AG. Paradoxical improvement of impulse conduction in cardiac tissue by partial cellular uncoupling. Science. 1997;275:841–844. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5301.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rohr S, Kucera JP, Kleber AG. Slow conduction in cardiac tissue, I: effects of a reduction of excitability versus a reduction of electrical coupling on microconduction. Circ Res. 1998;83:781–794. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.8.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rozanski GJ, Xu Z, Zhang K, Patel KP. Altered K+ current of ventricular myocytes in rats with chronic myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:H259–H265. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.1.H259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saffitz JE. Regulation of intercellular coupling in acute and chronic heart disease. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2000;33:407–413. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2000000400006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shaw RM, Rudy Y. Ionic mechanisms of propagation in cardiac tissue. Roles of the sodium and L-type calcium currents during reduced excitability and decreased gap junction coupling. Circ Res. 1997;81:727–741. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.5.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spach MS, Dolber PC, Heidlage JF. Influence of the passive anisotropic properties on directional differences in propagation following modification of the sodium conductance in human atrial muscle. A model of reentry based on anisotropic discontinuous propagation. Circ Res. 1988;62:811–832. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.4.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spach MS, Heidlage JF, Darken ER, Hofer E, Raines KH, Starmer CF. Cellular Vmax reflects both membrane properties and the load presented by adjoining cells. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:H1855–H1863. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.6.H1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stevenson WG, Friedman PL, Kocovic D, Sager PT, Saxon LA, Pavri B. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1998;98:308–314. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.4.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stevenson WG, Weiss JN, Wiener I, Rivitz SM, Nademanee K, Klitzner T, Yeatman L, Josephson M, Wohlgelernter D. Fractionated endocardial electrograms are associated with slow conduction in humans: evidence from pace-mapping. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1989;13:369–376. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stevenson WG, Weiss JN, Wiener I, Rivitz SM, Nademanee K, Klitzner T, Yeatman L, Josephson M, Wohlgelernter D. Fractionated endocardial electrograms are associated with slow conduction in humans: evidence from pace-mapping. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1989;13:369–376. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ursell PC, Gardner PI, Albala A, Fenoglio JJ, Jr, Wit AL. Structural and electrophysiological changes in the epicardial border zone of canine myocardial infarcts during infarct healing. Circ Res. 1985;56:436–451. doi: 10.1161/01.res.56.3.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vanag VK, Epstein IR. Inwardly rotating spiral waves in a reaction-diffusion system. Science (New York, NY. 2001;294:835–837. doi: 10.1126/science.1064167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Viswanathan PC, Shaw RM, Rudy Y. Effects of IKr and IKs heterogeneity on action potential duration and its rate dependence: a simulation study. Circulation. 1999;99:2466–2474. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.18.2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vrobel TR, Miller PE, Mostow ND, Rakita L. A general overview of amiodarone toxicity: its prevention, detection, and management. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1989;31:393–426. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(89)90016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu YQ, Pickoff AS, Clarkson CW. Developmental changes in the effects of lidocaine on sodium channels in rat cardiac myocytes. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 1992;262:670–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zaitsev AV, Berenfeld O, Mironov SF, Jalife J, Pertsov AM. Distribution of excitation frequencies on the epicardial and endocardial surfaces of fibrillating ventricular wall of the sheep heart. Circ Res. 2000;86:408–417. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.4.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zeng J, Laurita KR, Rosenbaum DS, Rudy Y. Two components of the delayed rectifier K+ current in ventricular myocytes of the guinea pig type. Theoretical formulation and their role in repolarization. Circ Res. 1995;77:140–152. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.