Abstract

Background

A paradox in epilepsy and psychiatry is that temporal lobe epilepsy is often predisposed to schizophrenic-like psychosis, whereas convulsive therapy can relieve schizophrenic symptoms. We have previously demonstrated that the nucleus accumbens is a key structure in mediating postictal psychosis induced by a hippocampal electrographic seizure.

Objective/Hypothesis

The purpose of this study is to test a hypothesis that accumbens kindling cumulating in a single (1-time) or repeated (5-times) convulsive seizures have different effects on animal models of psychosis.

Methods

Electrical stimulation at 60 Hz was applied to nucleus accumbens to evoke afterdischarges until one, or five, convulsive seizures that involved the hind limbs (stage 5 seizures) were attained. Behavioral tests, performed at 3 days after the last seizure, included gating of hippocampal auditory evoked potentials (AEP) and prepulse inhibition to an acoustic startle response (PPI), tested without drug injection or after ketamine (3 mg/kg s.c.) injection, as well as locomotion induced by ketamine or methamphetamine (1 mg/kg i.p.).

Results

Compared to non-kindled control rats, 1-time, but not 5-times, convulsive seizures induced PPI deficit and decreased gating of hippocampal AEP, without drug injection. Compared to non-kindled rats, 5-times, but not 1-time, convulsive seizures antagonized ketamine-induced hyperlocomotion, ketamine-induced PPI deficit and AEP gating decrease. However, both 1- and 5-times convulsive seizures, significantly enhanced methamphetamine-induced locomotion as compared to non-kindled rats.

Conclusions

Accumbens kindling ending with 1 convulsive seizure may induce schizophrenic-like behaviors, while repeated (≥ 5) convulsive seizures induced by accumbens kindling may have therapeutic effects on dopamine independent psychosis.

Keywords: Convulsive Seizures, Nucleus accumbens, Gating of hippocampal auditory evoked potentials, Prepulse inhibition, Kindling

Introduction

The relationship between epilepsy and schizophrenia has long fascinated neurologists and psychiatrists. The decrease in schizophrenic symptoms following convulsive seizures [1] led to the introduction of convulsive therapy [2]. On the other hand, schizophrenic-like behavior was frequently reported in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy [3–6].

In animal literature, changes in emotional and schizophrenia-like behaviors were observed following repeated temporal lobe seizures induced by electrical kindling [7–9]. The schizophrenic-like behaviors induced by hippocampal kindling are probably caused by hyperdopaminergic functions in the nucleus accumbens (NAc), activated by glutamatergic efferents from the temporal lobe structures, including the hippocampus and amygdala [10,11]. Dopaminergic inputs to the NAc come from the ventral tegmental area (VTA), part of the mesolimbic system [12]. Normal activity in the hippocampus is proposed to induce locomotor and other behaviors by releasing dopamine in the NAc [13]. However, hyperdopaminergic function in the mesolimbic dopamine system may lead to psychotic behaviors after repeated limbic seizures [7,9,14], or repeated VTA stimulation [15].

Schizophrenia-like symptoms in animals were evaluated by behavioral measures similarly applied to humans. Schizophrenic patients are unable to filter irrelevant sensory information, which can be measured by prepulse inhibition of startle reflex (PPI), also known as sensorimotor gating [16]. In addition, gating of auditory evoked potentials (AEP), a form of sensory gating, was deficient in schizophrenic patients as compared to healthy volunteers [17]. Schizophrenic symptoms were induced in healthy volunteers after administration of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist, ketamine [18,19]. Dopamine agent methamphetamine also readily induced psychosis in humans [20,21]. Psychosis relevant behaviors in animals, such as increase in locomotor activities, decrease in PPI and AEP gating was also readily induced by injection of psychotomimetic drugs such as ketamine or MK-801 [22,23].

Partial hippocampal kindling in rats, with 21 electrographic seizures or afterdischarges (ADs) without convulsions, result in PPI deficit and increase in methamphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion [9]. However, in a different study, amphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion was decreased after NAc kindling induced three convulsive (stage 5) seizures [24]. This suggests that convulsive seizures, and perhaps the location of the seizures, may determine whether the mesolimbic dopaminergic system was sensitized by (meth)amphetamine.

The purpose of this study was to investigate schizophrenia-like behaviors induced by NAc kindling in rats, and whether different behavioral outcomes were associated with the number of convulsive seizures. The NAc was selected since it was proposed as the brain area that mediates psychosis-related behaviors after temporal lobe seizures [14,25]. We expect that NAc kindling would result in schizophrenia-like behaviors although we are not aware of any existing literature. On the other hand, convulsive seizures in the NAc may have different effects than non-convulsive seizures, because kindling of the NAc to convulsive seizures resulted in decreased amphetamine-induced locomotion [24]. Other than studying psychosis measures such as PPI and hippocampal AEP gating, we also investigated whether hyperlocomotion after NAc kindling was induced by ketamine and methamphetamine, in order to distinguish sensitization by NMDA and dopaminergic receptors.

Animal and methods

Male Long-Evans hooded rats (Charles River Canada, St. Constance, Quebec, Canada) were housed in pairs in Plexiglas cages and kept on a 12/12 h light/dark cycle at a temperature of 22 ± 1 °C, with ad libitum food and water. All experimental procedures were approved by the local Animal Use Committee.

Surgery

Under sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg i.p.) anesthesia, the rats were implanted with bilateral pairs of recording electrodes (125 μm Teflon-insulated stainless steel wires) in stratum radiatum and stratum oriens of the hippocampal CA1 region (AP −3.5, L ± 2.7, V 2.3 and 3.3 from skull surface, units in mm), and in the NAc (AP ± 1.5, L ± 1.2, V 7.2 and V7.7), according to the stereotaxic atlas of Paxinos and Watson [26]. One jeweller’s screw was fixed in the skull over the cerebellum to serve as a recording ground. All electrodes and screws were finally anchored to the skull with dental cement. One week was allowed for the animals to recover from surgery.

Kindling

Afterdischarge (AD) in the NAc was induced by a 1-s train of 60 Hz, with pulses of 1 ms duration, with the cathode applied to the deep NAc electrode, and the shallow electrode serving as an anode. All electrodes from the hippocampus and the contralateral NAc were used for recording AD on polygraph paper. If an AD (defined to be high-amplitude paroxysmal activity longer than 3 s) was not evoked by an initial current amplitude of 50 μA, another stimulation train was given 10 min later, with the stimulus intensity increased by 50 μA until 300 μA, and then by 100 μA increments until 800 μA. Rats in which an AD could not be evoked at 800 μA intensity after several attempts were not used. ADs were then evoked at hourly intervals for five times per day until stage 4 seizure was induced. At stage 4 seizure, the stimulation interval was then set to 4 hours until stage 5 seizure was induced. The stage of behavioral seizure was rated by the scale of Racine [27]. The kindling procedure was stopped with one evoked stage 5 seizure, which was referred as the 1-time convulsive seizure (1CS) group, or continued until five stage 5 seizures (referred to as the 5-time convulsive seizure or 5CS group). For the latter group, rats were stimulated every day after the first stage 5 seizure, and if the first stimulation each day did not evoke a stage 5 seizure, another stimulation was delivered 4 h later.

Prepulse inhibition test (PPI)

Prepulse inhibition (PPI) and other behavioral tasks were tested 3 days after the last seizure. PPI was measured by SR-LAB (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA), using a piezoelectric accelerometer to detect startle amplitude [9]. PPI testing started immediately after the rat was put into the test chamber. After acclimating to 68-dB white noise, the rats were given different sound stimuli – a startle pulse only (120 dB 40-ms broad band burst), or a startle pulse preceded 100 ms by a prepulse (20-ms broad band noise) of intensity 73, 75, or 80 dB. For each test session, 50 trials were given in randomized order – 10 trials with startle pulse only, 10 trials with no auditory stimulation, and 10 trials with one of the three prepulse intensities followed by a startle pulse. PPI was measured as the difference between the response to the startle pulse alone and the response to prepulse-startle, or PPI (in percent) = 100 × [1 − (mean startle response amplitude after a prepulse/mean amplitude of response to startle alone)]. In this study, both individual prepulse intensities of 73, 75, 80 dB and the integrated prepulse intensity (mean of all prepulses) were used to calculate the PPI. In some experiments, ketamine (3 mg/kg s.c.) or saline (0.2 mL) was injected immediately before PPI testing.

Gating of hippocampal auditory evoked potentials (AEPs)

Auditory evoked potentials (AEPs) in the hippocampus were recorded in the afternoon after PPI measurements. Hippocampal electrodes were connected to a flexible cable that was led through an opening of the semi-restraining chamber. AEPs at the CA1 stratum radiatum electrode were acquired following auditory click pairs separated by a conditioning-test (C-T) interval of 520 ms; each click was a white-noise burst of 20 ms pulse duration and at 75 dB. Click pairs were given 15-s apart. Single sweeps of the auditory evoked potential were stored on the computer and those sweeps with clear movement or electrical artifacts were rejected online, and additional sweeps could also be rejected offline. Twenty-five sweeps were averaged in the average auditory evoked potential, from which the ratio of amplitude in response to the test (2nd) pulse and that in response to the conditioning (1st) pulse was used for data analysis. In some experiments, ketamine (3 mg/kg s.c.) or saline (0.2 mL) was injected immediately before AEP recordings.

Quantification of locomotor activity

Locomotor activity was recorded in rats different from those used for PPI/AEP measurements, at 3 days after the last seizure. Horizontal movements (locomotion) of a rat were measured by the number of interruptions of infrared beams in a Plexiglas chamber (69 cm × 69 cm × 49 cm). Four independent infrared sources, at 23 cm intervals, were located on a horizontal plane 5 cm above the floor, with photodiode detectors on the other side. Interrupts of the beams were counted and transferred to a microcomputer via an interface (Columbus Instruments). For testing the effect of ketamine (3 mg/kg s.c.) or equal volume of saline injection, a rat was habituated for 30 min in the chamber before injection, and infrared interruption counts per minute were recorded for 5 min before (baseline) and 30 min (30 time bins) after ketamine/saline injection. Increase of post-injection activity over the mean activity of the 5 min baseline was considered hyperlocomotion. For testing the effects of methamphetamine 1 mg/kg (i.p.), infrared interruption counts after injection were recorded every 10 minutes, for 2 hours (12 time bins) after injection.

Histology

Upon completion of experiments, the rat was deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital (80 mg/kg i.p.) and transcardially perfused with 0.9% saline followed with 4% formalin. The brain of the rat was removed and cut into 40 mm coronal sections with a freezing microtome. The brain sections were mounted on glass slides and stained with thionin for identifying locations of the electrodes.

Statistics

Values were expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed by t-test, or one/two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) as appropriate. ANOVA with significant main or interaction effect was followed by post-hoc Newman-Keuls test. Significance level was set at P<0.05.

Results

Afterdischarge (AD) threshold and AD durations during kindling

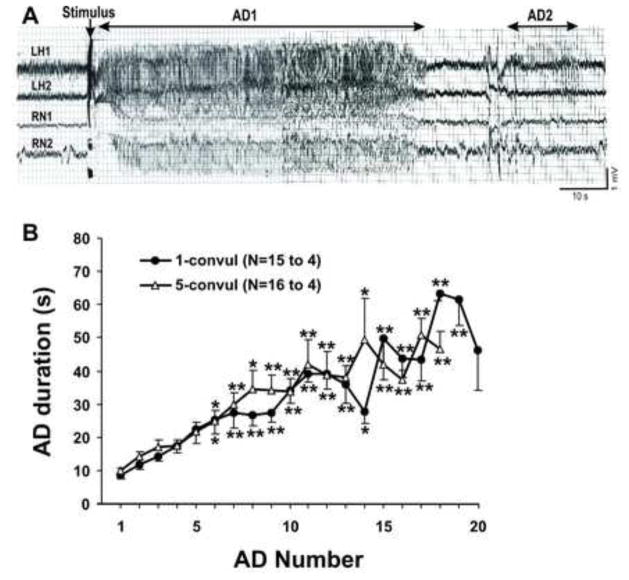

ADs in the ipsilateral hippocampus and the contralateral NAc (Fig. 1A) were induced by 60-Hz stimulation of NAc on one side. In some rats, AD in the hippocampus appeared earlier and lasted longer than that in the NAc (data not shown). Sometimes, secondary ADs appeared only in the hippocampus but not in the NAc (Fig. 1A), suggesting independent generation of ADs in the hippocampus and NAc.

Figure 1.

A: Representative EEG traces recorded at stratum radiatum (LH1) and stratum oreins (LH2) of the ipsilateral hippocampus, and the contralateral nucleus accumbens (RN1 and RN2) following stimulation in the left nucleus accumbens with 1-s train of 60 Hz, 800 μA for the 11th afterdicharge (AD). AD1: primary AD, AD2: secondary AD, illustrated for LH1. Note that AD2 only appeared in the hippocampus, but not in the nucleus accumbens. B: AD duration plotted with number of AD during kindling, in 1-time (1-convul) and 5-times (5-convul) convulsive seizure treated rats. Rats were removed from respective groups after reaching 1- or 5-times convulsive seizures; number of rats in1-convul group (N=15 for AD 1–7; N>6, AD 8–19, N=5, AD 20) and 5-convul group (N=17, AD1–7; N>6, AD 8–16, N>4, AD17–18). *P < 0.05; **P <0.01, significant different from first AD after Newman-Keuls post-hoc test following a significant two-way ANOVA.

The AD duration in the hippocampus or NAc increased steadily with kindling (Fig. 1). Few stage 2 (mouth movements) or stage 3 (forelimb clonus alone) seizures were observed before the first stage 4 (forelimb clonus with falling) seizure, and the first stage 5 seizure followed in the next two stimulations. The average number of ADs needed for the first stage 5 seizure was 16 ± 1 (n=15) in the 1-time convulsive seizure (1CS) rats, not significantly different (t(30.7) = 1.0, P=0.33, t-test) from 14 ± 1 (n=16) in 5-times convulsive seizure (5CS) rats. The 1CS group experienced 1.6 ± 0.21 stage 4 seizures before the first stage 5 seizure, and the 5CS group experienced 1.8 ± 0.25 stage 4 seizures before the first stage 5 seizure, which was not significantly different from each other (t(31.7) = 0.5, P = 0.63, t test). The average AD duration of the first convulsive seizure was 56 ± 4 s in 1CS rats, not significantly different (t(31.9)=0.45, P=0.67, t test) from 54 ± 5 s in the 5CS rats. The average AD duration of the 2nd to 5th stage 5 seizure in the 5CS group ranged from 45 ± 4 to 51 ± 5 s. The AD stimulus intensity was 526 ± 28 μA in 1CS rats, not different from (t(40.0) = 2.01, P > 0.05, t-test) 602 ± 26 μA in the 5CS rats.

Effects of convulsive seizures and ketamine on PPI

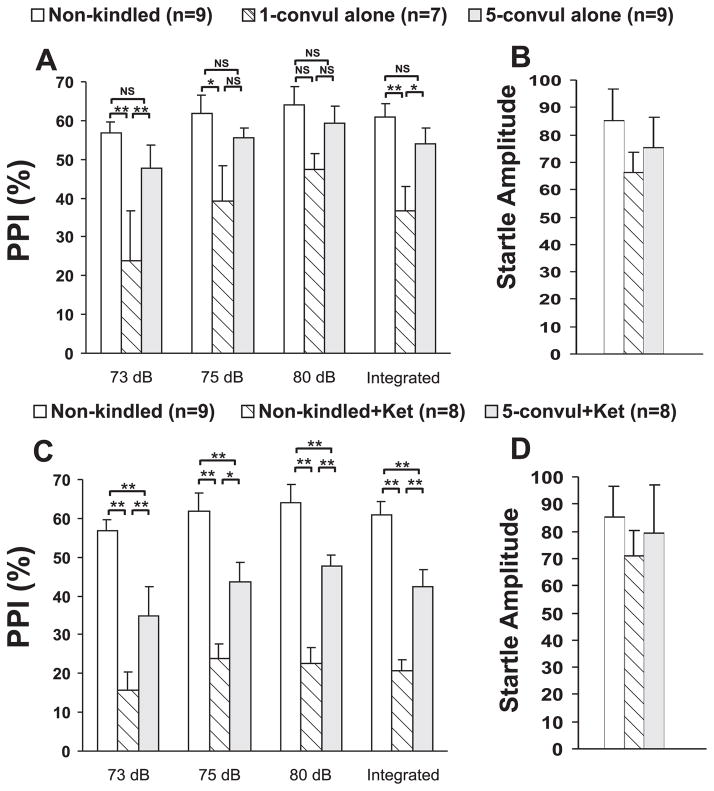

PPI was assessed in three groups – non-kindled, 1CS and 5CS groups. Two-way (group x prepulse intensity) repeated measures analysis showed a group effect on PPI [F(2,22) = 7.02, P < 0.005, Fig. 2A; two-way repeated measures ANOVA]. There was also a significant effect of prepulse intensity on PPI [F(2,44) = 6.86, P < 0.005]. The integrated PPI also showed a significant group effect [F(2,22 = 6.59, P < 0.01, one-way completely randomized ANOVA]. Newman-Keuls post-hoc test indicated that the integrated PPI was not significantly different between non-kindled and 5CS groups, but it was significantly different between 1CS and non-kindled groups, and between 1CS and 5CS groups (Fig. 2A), There were no significant differences in startle amplitude among the three groups [F(2,22) = 0.71, P = 0.50, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Average prepulse inhibition (PPI) in percent (%) of auditory startle response following different treatments. A and B. PPI (A) and startle amplitude (B) in non-kindled rats, 1-time and 5-times convulsive seizures rats. C and D. PPI (C) and startle response amplitude (D) in non-kindled rats and 5-times convulsive seizure rats given ketamine (3 mg/kg, sc), as compared to not injected non-kindled rats. **P < 0.01, * P < 0.05, NS, not significant, Newman-Keuls post-hoc test following a significant two-way ANOVA.

PPI after ketamine injection of 3 mg/kg (s.c.) was evaluated in non-kindled and 5CS rats, and not-injected, non-kindled rats (Fig. 2C). These 3 groups of rats showed a significant group effect [F(2,22) = 13.68, P < 0.001, two-way (group x prepulse intensity) repeated measures ANOVA]. Newman-Keuls post-hoc test showed that PPI was significantly lower in the ketamine-injected non-kindled rats, or the ketamine-injected 5CS rats, as compared to not-injected, non-kindled rats (Fig. 2C), but ketamine’s effect on 5CS rats was smaller than that on non-kindled rats. Integrated PPI showed the same significant differences as the PPI following each individual prepulse (Fig. 2C). There was also a significant effect of prepulse intensity on PPI [F(2,44) = 9.63, P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA]. There were no significant differences in startle amplitude among the groups of rats [F(2,22) = 0.41, P = 0.67, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 2D).

Effects of convulsive seizures and ketamine on hippocampal auditory evoked potentials

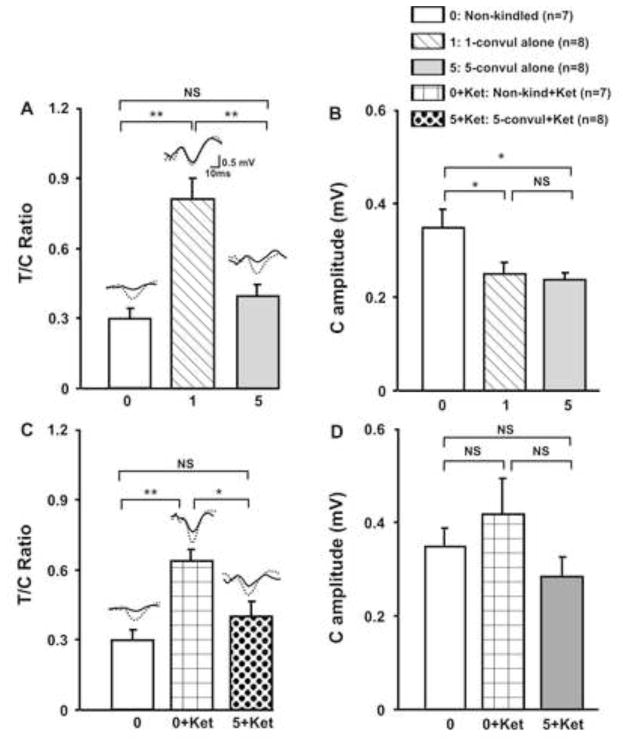

T/C ratios of the hippocampal auditory evoked potentials in 3 groups of rats – non-kindled (n=7), 1CS (n=8), and 5CS rats (n=8) – were found to be significantly different [group effect F(2,20) = 16.4, P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 3A]. Post-hoc Newman-Keuls test indicated that the T/C ratio was significantly higher in the 1CS, but not the 5CS group, as compared to the non-kindled group (Fig. 3A). The conditioning-pulse response amplitudes were also significantly different among the 3 groups [F(2,20) = 4.95, P < 0.02, one-way ANOVA], and post-hoc Newman-Keuls test showed that the amplitude of the conditioning-pulse response was higher in the non-kindled group than either the 1CS or 5CS group (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Average test to conditioning auditory potential response ratio (T/C ratio) and conditioning response amplitude (C Amplitude) in the hippocampus following different treatments. A. Non-kindled rats showed a T/C ratio, not different from 5-times convulsive seizures group (5-convul alone), but significantly smaller than 1-time convulsive seizure (1-convul alone) group. B. C amplitude was decreased in 1- and 5-times convulsive seizure groups, as compared to non-kindled group. C. T/C ratio was higher in non-kindled rats given 3 mg/kg s.c. ketamine (0+Ket), but not in 5-time convulsive seizures rats given ketamine (5+Ket), as compared to not injected non-kindled rats. D. C amplitude was not significantly different among the groups. **P < 0.01, * P < 0.05, NS, not significant, Newman-Keuls post-hoc test following a significant one-way ANOVA.

T/C ratio after ketamine injection of 3 mg/kg (s.c.) was evaluated in non-kindled rats and 5CS rats, and compared to not-injected, non-kindled rats (Fig. 3C). The T/C ratio of these 3 groups of rats showed a significant group effect [F(2,19) = 10.7, P < 0.0008, one-way ANOVA], and Newman-Keuls post-hoc test indicated a significant difference between non-injected and ketamine injected non-kindled rats, and between the post-ketamine conditions in non-kindled rats and 5CS rats (Fig. 3C). However, conditioning pulse response amplitudes were not significantly different among the 3 groups [F(2,19) = 1.56, P > 0.2, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 3D].

Effects of convulsive seizures on ketamine-induced hyperlocomotion

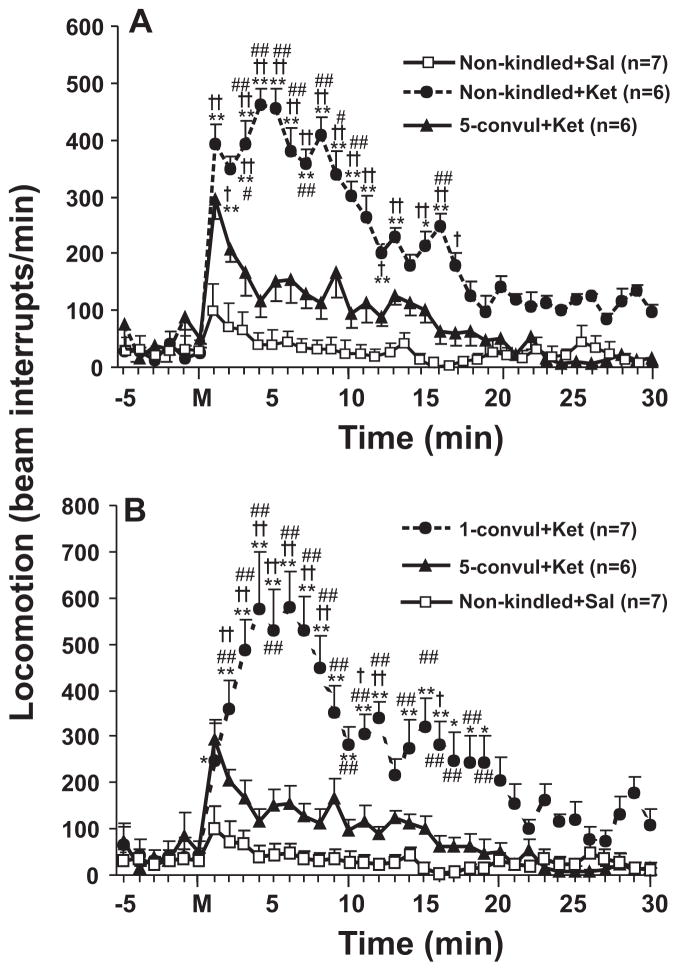

Four groups of rats were used to evaluate the effects of 1-time (1CS) and 5-times (5CS) convulsive seizure on ketamine-induced hyperlocomotion. Two-way (group x time) repeated measures ANOVA showed a main group effect [F(3,22) = 61.4, P < 0.0001, Fig. 4A]. Ketamine-induced hyperlocomotion was significantly reduced in 5CS rats as compared to non-kindled rats (Fig. 4A), or 1CS rats (Fig. 4B). Newman-Keuls post-hoc test indicated that there were was no significant difference at any time points between saline-injected, non-kindled rats and ketamine-injected 5CS rats, other than a transient increase at 1 minute after injection (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Horizontal locomotor activity, as indicated by interruption of infrared beams, was plotted in time before and after ketamine (3 mg/kg, s.c.) in different groups of rats. A. Locomotor activity of non-kindled rats after ketamine (Non-kindled + Ket) was significant different, while that of 5-times convulsive seizure rats after ketamine (5-convul + Ket) was not different, from locomotor activity induced after saline in non-kindled rats (Non-kindled + Sal). B. Locomotor activity of 1-time convulsive seizure rats after ketamine (1-convul + Ket) was significantly different from locomotor activity induced in “Non-kindled + Sal” rats and 5-times convulsive seizure rats. +P < 0.05; ++P < 0.01, significant difference between the same time point of each group, and the “Non-kindled + Sal” group; #P < 0.05; ##P < 0.01, significant difference between the same time point of each group, and the “5-convul + Ket” group; * P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, significant difference between baseline mean value and after drug at different time points; all tests were Newman-Keuls post-hoc following a significant two-way repeated measures ANOVA.

In contrast to 5CS treatment, 1CS treatment did not prevent ketamine-induced hyperlocomotion. Compared to saline alone injection in non-kindled rats, ketamine injection significantly increased locomotion to a similar level in both non-kindled rats and 1CS rats [F(2,527) = 324.13, P<0.0001, two-way repeated measures ANOVA; Fig. 4B].

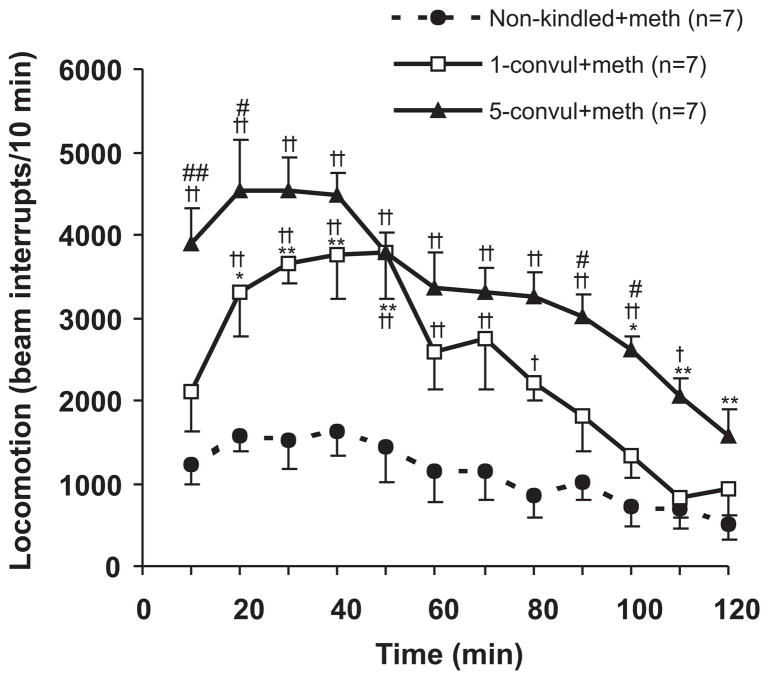

Effects of convulsive seizures on methamphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion

Methamphetamine-induced horizontal locomotion was assessed in non-kindled rats, 1CS and 5CS rats. Methamphetamine-induced locomotion showed a significant group effect [F(2,18) = 19.56, P < 0.0001, two-way (group x time) repeated measures ANOVA; Fig. 5], and a significant time effect [F(11,198) = 26.34, P < 0.0001]. Newman Keuls post-hoc test further indicated horizontal movement after methamphetamine was significantly higher in 5CS rats as compared to 1CS rats (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Methamphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion, indicated by interruption of infrared beams, after 1- and 5-times convulsive seizures, as compared to a non-kindled group. *P <0.05; **P<0.01: different from 5 min after injection within the same group; +P<0.05; ++P < 0.01: different from non-kindled group at the same time points; #P <0.05; ##P < 0.01 different between 1- and 5-times convulsive seizure treated rats; Newman-Keuls post-hoc test following a significant repeated measures two-way ANOVA.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that electrical kindling of the NAc resulted in dual effects on animal models of psychosis. One-time NAc-induced convulsive seizure induced deficit of PPI and decreased gating of hippocampal AEPs. In contrast, 5-times convulsive seizures normalized PPI and AEP gating deficits, and prevented ketamine-induced behavioral deficits hyperlocomotion, PPI and AEP gating). Interestingly, rats after both 1- and 5-times accumbens convulsive seizures showed significantly enhanced methamphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion.

A most fascinating phenomenon in the literature of psychosis is that temporal lobe seizures may induce schizophrenic-like symptoms [3–6], while convulsive seizures may relieve some symptoms of schizophrenia [28]. A generalized seizure of sufficient duration is considered to be necessary for effective electroconvulsive therapy [29]. The present study embodies this paradox by showing that repeated, NAc-evoked non-convulsive seizures (ending with one convulsive, stage 5 seizure) induced schizophrenia-like symptoms, and additional convulsive (stage 5) seizures relieved the schizophrenia-like symptoms and suppressed those induced by ketamine.

Effects of 1- and 5-times convulsive seizures on gating of hippocampal AEP and PPI

This study shows that accumbens kindling to 1CS resulted in a decrease in hippocampal AEP gating, as compared to non-kindled animals. Gating of hippocampal AEP was suggested to be mediated by local GABAergic interneurons [30,31], in particular through GABAB receptors [32,33]. Gating of AEPs in the hippocampus was further modulated by the medial septum [34,35]. Hippocampal seizures were shown to decrease efficacy of presynaptic GABAB receptors, in particular those on glutamatergic terminals in the hippocampus [36], which may contribute to the loss of hippocampal AEP gating.

Hippocampal ADs during accumbens kindling were of high amplitudes (>4 mV) and appeared to be locally and independently generated. It is not known how the seizure spread to the hippocampus after NAc stimulation, since to our knowledge, there are no direct projections from the NAc to the hippocampus. Instead, the NAc projects to the septum [37,38], which may then drive the hippocampal AD. Alternatively, accumbens paroxysmal activity may backpropagate through the hippocampal-accumbens nerve terminals, as was documented in thalamocortical system [39]. Electrical stimulation of the NAc was shown to affect long-term potentiation in the dentate gyrus of hippocampus [40], supporting an influence of the NAc on neural activity in the hippocampus.

This study also showed that accumbens kindling in the 1CS group resulted in a PPI deficit. This adds the NAc to a list of limbic structures from which seizures induced PPI loss. PPI loss was found after full kindling of the medial prefrontal cortex and partial kindling of the dorsal hippocampus [9,41] and within 10 min after full kindling of the basolateral amygdala [42], but not after kindling of the ventral hippocampus or perirhinal cortex [43]. Neural circuits mediating normal PPI include the septohippocampal system [35,44], pedunculopontine nucleus, and NAc [45]. It is not known whether the entire PPI-related neural circuit was affected by accumbens kindling.

In this study, although psychosis relevant behaviors were shown after 1CS, it is unlikely that one-time convulsive seizure may cause psychosis. The first stage 5 seizure was used in this study as a convenient marker to stop kindling for the 1CS group, and while we did not investigate whether 1CS may alter the pathological effect of kindling, it was likely that the 15 ADs (on the average) before the 1CS were responsible for the kindling-induced psychosis. Previous study showed that partial hippocampal kindling, 21 ADs that did not induce stage 5 seizures were sufficient to induce psychosis [9].

In contrast to 1CS, 5CS did not alter PPI or hippocampal AEP gating, tested 3 days after the last seizure, as compared to the non-kindled rats. Ketamine-induced AEP gating loss was abolished, while ketamine-induced PPI loss was diminished in 5CS as compared to normal, non-kindled rats. It may be suggested that the 4 additional convulsive seizures (difference between 5CS and 1CS rats) restored normal PPI and AEP gating, which will be further discussed below.

Effects of convulsive seizures on ketamine- or methamphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion

Ketamine-induced locomotion in 1CS rats was greatly increased from that in non-kindled rats. This shows an increased sensitivity to ketamine in accumbens kindled rats. By contrast, ketamine-induced locomotion of 5CS rats resembled that of non-kindled rats, suggesting that repeated convulsive seizures normalized the ketamine-induced locomotion in accumbens kindled rats. Methamphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion showed yet another property – it increased from non-kindled rats to 1CS rats, and further increased in 5CS rats. Thus, NAc convulsive seizures were selective on suppressing hyperlocomotion induced by different agents, i.e., convulsive seizures only prevent locomotion induced by an NMDA antagonist (ketamine) but not that induced by a dopamine agonist (methamphetamine). The reasons underlying the difference between ketamine and methamphetamine induced locomotion is not completely known, and we suggest that ketamine-induced locomotion may not be critically dependent on dopamine release in the NAc. Ouagazzal et al. [46] showed that hyperlocomotion induced by d-amphetamine, but not that induced by NMDA antagonist MK-801, was blocked by 6-hydroxydopamine depletion of dopamine (~80%) in the NAc. However, Irifune et al. [47] showed that ketamine-induced locomotion in mice was attenuated by moderate (~55%) depletion of dopamine in the NAc by ventricularly injected 6-hydroxydopamine.

The mechanisms of how convulsive seizures suppressed interictal PPI and AEP deficits, or ketamine-induced behavioral disruptions are not known. The stage 5 convulsive seizures involve generalized paroxysmal activity from the frontal cortex, which may activate therapeutic mechanisms through frontal cortical projection to mesolimbic areas, including the NAc. A possible therapeutic mechanism may be activation of opioid μ receptors in the NAc, which mediated postictal behavioral depression after convulsive seizures [48–50]. Three days after repeated morphine (μ receptor agonist) exposure for 7–14 days, excitability of NAc medium-size spiny neurons was decreased [51] and NMDA/non-NMDA receptor expression were reduced [52]. Opiod μ receptor agonists decreased the frequency of spontaneous excitatory and inhibitory currents in vitro [53], antagonized apomorphine-induced PPI deficit in behaving mice [54] and improved PPI in normal humans [55]. These accumulative findings suggest that additional neural plasticity, possibly involving μ receptors, may be induced in 5CS rats, which may reverse the interictal PPI/AEP gating deficit and suppress ketamine-induced hyperlocomotion.

In summary, the present study provides insights to the literature of human epilepsy related schizophrenic-like psychosis and the therapeutic effects of convulsive therapy. Further studies are needed to elucidate the neural mechanisms by which convulsive seizures may help to relieve psychiatric symptoms.

Acknowledgments

The research was financially supported by operating grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures

The authors reported no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Muller G. Anfalle bei schizophrenen erkrankringer. Allgem Z Psychia. 1930;93:235–240. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meduna L. Die Konvulsionstherapie der Schizophrenie. Carl Marhold Verlagsbuchhandlung; Halle: 1937. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slater E, Beard AW. The schizophrenia-like psychoses of epilepsy I. Psychiatric aspects. Br J Psychiatry. 1963;109:95–150. doi: 10.1192/bjp.109.458.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trimble M. The relationship between epilepsy and schizophrenia: a biochemical hypothesis. Biol Psychiatry. 1977;12:299–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mace CJ. Epilepsy and schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:439–445. doi: 10.1192/bjp.163.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dedeurwaerdere S, Boets S, Janssens P, Lavreysen H, Steckler T. In the grey zone between epilepsy and schizophrenia: alterations in group II metabotropic glutamate receptors. Acta Neurol Belg. 2015;115:221–232. doi: 10.1007/s13760-014-0407-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adamec R. Does kindling model anything clinically relevant? Biol Psychiatry. 1990;27:249–279. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(90)90001-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalynchuk LE, Pinel JP, Treit D, McEachern JC, Kippin TE. Persistence of the interictal emotionality produced by long-term amygdala kindling in rats. Neuroscience. 1998;85:1311–1319. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma J, Leung LS. Schizophrenia-like behavioral changes after partial hippocampal kindling. Brain Res. 2004;997:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelley AE, Domesick VB. The distribution of the projection from the hippocampal formation to the nucleus accumbens in the rat: an anterograde- and retrograde-horseradish peroxidase study. Neuroscience. 1982;7:2321–2335. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pennartz CM, Groenewegen JH, Lopes da Silva FH. The nucleus accumbens as a complex of functionally distinct neuronal ensembles: An integration of behavioural, electrophysiological and anatomical data. Prog Neurobiol. 1994;42:719–761. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ungerstedt U. Stereotaxic mapping of the monoamine pathways in the rat brain. Acta Physiol Scand (Suppl) 1971;367:1–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201x.1971.tb10998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blaha CD, Yang CR, Floresco SB, Barr AM, Phillips AG. Stimulation of the ventral subiculum of the hippocampus evokes glutamate receptor-mediated changes in dopamine efflux in the rat nucleus accumbens. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9:902–911. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leung LS, Ma J, McLachlan RS. Behaviors induced or disrupted by complex partial seizures. Neurosci BioBehav Rev. 2000;24:763–775. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens JR, Livermore A., Jr Kindling of the mesolimbic dopamine system: animal model of psychosis. Neurology. 1978;28:36–46. doi: 10.1212/wnl.28.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braff DL, Geyer MA, Swerdlow NR. Human studies of prepulse inhibition of startle: normal subjects, patient groups, and pharmacological studies. Psychopharmacology. 2001;156:234–258. doi: 10.1007/s002130100810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freedman R, Adler LE, Myles-Worsley M, Nagamoto HT, Miller C, Kisley M, McRae K, Cawthra E, Waldo M. Inhibitory gating of an evoked response to repeated auditory stimuli in schizophrenic and normal subjects. Human recordings, computer simulation, and an animal model. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:1114–1121. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120052009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krystal JH, Karper LP, Seibyl JP, Freeman GK, Delaney R, Bremner JD, et al. Subanesthetic effects of the noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, ketamine, in humans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:199–214. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boeijinga PH, Soufflet L, Santoro F, Luthringer R. Ketamine effects on CNS responses assessed with MEG/EEG in a passive auditory sensory-gating paradigm: an attempt for modelling some symptoms of psychosis in man. J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21:321–337. doi: 10.1177/0269881107077768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sato M, Numachi Y, Hamamura T. Relapse of paranoid psychotic state in methamphetamine model of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1992;18:115–122. doi: 10.1093/schbul/18.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomiyama G. Chronic schizophrenia-like states in methamphetamine psychosis. Jpn J Psychiatry Neurol. 1990;44:531–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1990.tb01626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma J, Leung LS. The supramammillo-septal-hippocampal pathway mediates sensorimotor impairment and hyperlocomotion induced by MK-801 and ketamine in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2007;19:961–974. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0667-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma J, Tai SK, Leung LS. Septohippocampal GABAergic neurons mediate the altered behaviors induced by N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists. Hippocampus. 2012 doi: 10.1002/hipo.22039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ehlers CL, Koob GF. Locomotor behavior following kindling in three different brain sites. Brain Res. 1985;326:71–79. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91385-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma J, Brudzynski SM, Leung LS. Involvement of the nucleus accumbens-ventral pallidal pathway in postictal behavior induced by a hippocampal afterdischarge in rats. Brain Res. 1996;739:26–35. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)00793-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 6. San Diego: Academic; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Racine RJ. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation: II. Motor seizure. Electroenceph Clin Neurophysiol. 1972;32:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(72)90177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tharyan P, Adams CE. Electroconvulsive therapy for schizophrenia (review) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015:CD000076. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Psychiatric Association. The practice of electroconvulsive therapy: recommendations for treatment, training, and privileging: a task force report of the American Psychiatric Association. 2. Washington, D.C: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freund TF, Buzsaki G. Interneurons of the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 1996;6:345–470. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:4<347::AID-HIPO1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller CL, Freedman R. The activity of hippocampal interneurons and pyramidal cells during the response of the hippocampus to repeated auditory stimuli. Neuroscience. 1995;69:371–381. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00249-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moxon KA, Gerhardt GA, Gulinello M, Adler LE. Inhibitory control of sensory gating in a computer model of the CA3 region of the hippocampus. Biol Cybern. 2003;88:247–264. doi: 10.1007/s00422-002-0373-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma J, Leung LS. GABA(B) receptor blockade in the hippocampus affects sensory and sensorimotor gating in Long-Evans rats. Psychopharmacology. 2011;217:167–176. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2274-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma J, Tai SK, Leung LS. Ketamine-induced gating deficit of hippocampal auditory evoked potentials in rats is alleviated by medial septum inactivation and antipsychotic drugs. Psychopharmacology. 2009;206:457–467. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1623-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller CL, Freedman R. Medial septal neuron activity in relation to an auditory sensory gating paradigm. Neuroscience. 1993;55:373–380. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90506-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poon N, Kloosterman F, Wu C, Leung LS. Presynaptic GABAB receptors on glutamatergic terminals of CA1 pyramidal cells decrease in efficacy after partial hippocampal kindling. Synapse. 2006;59:125–134. doi: 10.1002/syn.20223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conrad LCA, Pfaff DW. Autoradiographic tracing of nucleus accumbens efferents in the rat. Brain Res. 1976;113:589–596. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Powell EW, Leman RB. Connections of the nucleus accumbens. Brain Res. 1976;105:389–403. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90589-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gutnick MJ, Prince DA. Thalamocortical relay neurons: antidromic invasion of spikes from a cortical epileptogenic focus. Science. 1972;176:424–426. doi: 10.1126/science.176.4033.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kudolo J, Tabassum H, Frey S, López J, Hassan H, Frey JU, Berdago JA. Electrical and pharmacological manipulations of the nucleus accumbens core impairs synaptic plasticity in the dentate gyrus of the rat. Neuroscience. 2010;168:723–731. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma J, Leung LS. Kindled seizure in the prefrontal cortex activated behavioral hyperactivity and increase in accumbens gamma oscillations through the hippocampus. Behav Brain Res. 2010;206:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koch M, Ebert U. Deficient sensorimotor gating following seizures in amygdala-kindled rats. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:290–297. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00397-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Howland JG, Hannesson DK, Barnes SJ, Phillips AG. Kindling of basolateral amygdala but not ventral hippocampus or perirhinal cortex disrupts sensorimotor gating in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2007;177:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koch M. The septohippocampal system is involved in prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle response in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1996;110:468–477. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.3.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swerdlow NR, Geyer MA, Braff DL. Neural circuit regulation of prepulse inhibition of startle in the rat: current knowledge and future challenges. Psychopharmacology. 2001;156:194–215. doi: 10.1007/s002130100799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ouagazzal A, Nieoullon A, Arnatric M. Locomotor activation induced by MK-801 in the rat: postsynaptic interaction with dopamine receptors in the ventral striatum. Eur J Pharmacology. 1994;251:229–236. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90404-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Irifune M, Shimizu T, Nomoto M. Ketamine-induced hyperlocomotion associated with alteration of presynaptic components of dopamine neurons in the nucleus accumbens of mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;40:399–407. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90571-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caldecott-Hazard S, Engel J., Jr Limbic postictal events: anatomical substrates and opioid receptors involvement. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol & Biol Psychiat. 1987;11:389–418. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(87)90014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Long JJ, Ma J, Leung LS. Behavioral depression induced by an amygdala seizure and the opioid fentanyl was mediated through the nucleus accumbens. Epilepsia. 2009;50:1953–1961. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma J, Boyce R, Leung LS. Nucleus accumbens mu opioid receptors mediate immediate postictal decrease in locomotion after an amygdaloid kindled seizure in rats. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;17:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heng LJ, Yang J, Liu YH, Wang WT, Hu SJ, Gao GD. Repeated morphine exposure decreased the nucleus accumbens excitability during shortterm withdrawal. Synapse. 2008;62:775–782. doi: 10.1002/syn.20551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spijker S, Houtzager SW, De Gunst MC, De Boer WP, Schoffelmeer AN, Smit AB. Morphine exposure and abstinence define specific stages of gene expression in the rat nucleus accumbens. FASEB J. 2004;18:848–850. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0612fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ma Y-Y, Cepeda C, Chatta P, Franklin L, Evans PJ, Levine MS. Regional and cell-type-specific effects of DAMGO on striatal D1 and D2 dopamine receptor-expressing medium-sized spiny neurons. ASN Neuro. 2012;4 doi: 10.1042/AN20110063. art:e00077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ukai M, Okuda A. Endomorphin-1, an endogenous mu-opioid receptor agonist, improves apomorphine-induced impairment of prepulse inhibition in mice. Peptides. 2003;24:741–744. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(03)00123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Quednow BB, Csomor PA, Chmiel J, Beck T, Vollenweider FX. Sensorimotor gating and attentional set-shifting are improved by the mu-opioid receptor agonist morphine in healthy human volunteers. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11:655–669. doi: 10.1017/S1461145707008322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]