Abstract

Purpose

Despite a growing literature on the influence of social support on mental health, little is known about the relationship between social support and specific psychiatric disorders for African Americans, such as PTSD. This study investigated the relationship between social support, negative interaction with family and 12-month PTSD among African Americans.

Methods

Analyses were based on a nationally representative sample of African Americans from the National Survey of American Life (n=3,315). Social support variables included emotional support from family, frequency of contact with family and friends, subjective closeness with family and friends, and negative interactions with family.

Results

Results indicated that emotional support from family is negatively associated with 12-month PTSD while negative interaction with family is predictive of 12-month PTSD. Additionally, a significant interaction indicated that high levels of subjective closeness to friends could offset the impact of negative family interactions on 12-month PTSD.

Conclusions

Overall, study results converged with previously established findings indicating that emotional support from family is associated with 12-month PTSD, while, negative interaction with family is associated with increased risk of 12-month PTSD. The findings are discussed in relation to prior research on the unique association between social support and mental health among African Americans.

Keywords: PTSD, family, friendships, African Americans, informal social support

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental health problem that affects 6.8% to 7.3% of Americans throughout their lifetime (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005; Roberts, Gilman, Breslau, Breslau, & Koenen, 2011) and has a 12-month prevalence rate of 3.5% (Kessler et al., 2005). Rates may be even higher for African Americans, with prior research estimating lifetime prevalence rates of 8.7% and 12-month prevalence rates of 3.80% for this group (Himle, Baser, Taylor, Campbell, & Jackson, 2009; Roberts et al., 2011). PTSD is associated with a range of functional impairments as well as high levels of disability (Breslau, Lucia, & Davis, 2004; Burriss, Ayers, Ginsberg, & Powell, 2008). With respect to functioning within social contexts, individuals living with PTSD frequently find it difficult to interact with friends and family due to their PTSD symptoms (Breslau et al., 2004). Exacerbation of PTSD symptoms tends to lead to tension, disagreements, and conflicts in personal relationships. Further, PTSD is also commonly associated with learning and memory impairments (Burriss et al., 2008) and is comorbid with major depressive disorder (Amaya-Jackson et al., 1999) and substance abuse (Buckley, Mozley, Bedard, Dewulf, & Greif, 2004; Thomas et al., 2010)—all of which have consequences for social functioning and personal relationships. Social relationships may be particularly important in understanding African Americans’ mental health, (Chatters, Taylor, Woodward, & Nicklett, 2015; Lincoln, 2000; Taylor, Chae, Lincoln, & Chatters, 2015)as prior research has found that positive relationship qualities, such as social support and subjective closeness, are predictive of more favorable mental health outcomes, and negative relationship qualities, such as negative interactions, are predictive of poorer mental health outcomes (Lincoln, 2000; Nguyen, Chatters, Taylor, & Mouzon, 2015; Taylor et al., 2015). The purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between social support, negative interactions and 12-month PTSD in a nationally representative sample of African Americans in the U.S.

Traditionally, research on social relations has conceptualized social networks as a person centered web of social relationships that are defined by two distinct domains—structure (e.g., size, composition) and function (i.e., provision of various types of support; Berkman & Glass, 2000). Informal social support encompasses assistance that is exchanged between social network members, such as family and friends and is manifested in various forms such as instrumental, informational, and emotional assistance (Berkman & Glass, 2000; House, 1981). Instrumental support represents tangible help that includes money, transportation, assistance with household chores, and food. Informational support is the provision of advice, suggestions, and information. Emotional support refers to actions of network members that make the individual feel loved and cared for and affirm their sense of self-worth.

A small but emerging body of research examines the role of informal social support in buffering against the development of PTSD and mitigating its severity. Individuals who have high levels of social support are less likely to be diagnosed with PTSD after experiencing a traumatic event (Adams & Boscarino, 2006; Arnberg, Hultman, Michel, & Lundin, 2012; Galea, Ahern, et al., 2002; Kilpatrick et al., 2007). Furthermore, for persons with PTSD, those who have high levels of social support tend to exhibit fewer PTSD symptoms (Andrews, Brewin, & Rose, 2003; Bonanno, Galea, Bucciarelli, & Vlahov, 2007; Coker et al., 2002; Glynn et al., 2003; Schumm, Briggs-Phillips, & Hobfoll, 2006). In particular, receipt of emotional and instrumental support appear to be strongly predictive of lower levels of PTSD symptoms (Glynn et al., 2003). In contrast, negative interactions with others (e.g., criticisms, conflicts) are associated with a greater probability of being diagnosed with PTSD (Burke, Neimeyer, & McDevitt-Murphy, 2010), exacerbation of PTSD symptoms (Andrews et al., 2003; Ullman, Townsend, Filipas, & Starzynski, 2007; Zoellner, Foa, & Brigidi, 1999), and higher PTSD severity (Zoellner et al., 1999).

Two causal pathways have been suggested to explain the relation between social support, negative interaction and PTSD. The social causation perspective posits that the social environment contributes to one’s mental health status (Dohrenwend, 2000; Guay, Billette, & Marchand, 2006). Further, because social support is considered a social resource that individuals may draw upon in coping with trauma, the lack of social support inhibits one’s ability to effectively cope with the trauma which can lead to the development of PTSD (Dohrenwend, 2000; Guay et al., 2006). Similarly, negative interactions with one’s social network members can inhibit one’s ability to cope effectively with experienced trauma, which then leads to the development of PTSD. In contrast, the social selection perspective suggests a different causal sequence in that one’s mental health status contributes to one’s social environment (Dohrenwend, 2000; Guay et al., 2006). In other words, PTSD symptoms, such as anger, irritability and social isolation, interfere with one’s social functioning and personal relationships, which then leads to decreased social support as well as negative interactions with others.

Available evidence supports both of these perspectives and suggests that the relation between social relationships and PTSD is bidirectional. For example, Kaniasty and Norris’ (2008) study of natural disaster survivors showed that shortly after a disaster, the lack of social support predicted the development of PTSD, which suggests a social causation explanation. However, at l8 months post-disaster, the lack of social support predicted the development of PTSD, and PTSD predicted the lack of social support, suggesting that both social causation and social selection are operating at this time point. Finally, at 24 months post-disaster, the authors found that PTSD predicts the lack of social support, indicating social selection.

While most anxiety disorders are less prevalent among African Americans than whites, lifetime estimates of PTSD among African Americans (8.7%) are higher than that of Whites (7.4%) (Himle et al., 2009; Roberts et al., 2011). Despite this fact, few studies have focused specifically on this population. More recently, a limited number of studies examining the relation between social support and PTSD among African Americans have yielded diverging results. Bryant-Davis et al.’s (2011) study of African American women recovering from sexual assault indicated that lower levels of social support predicted higher levels of PTSD symptoms. However, Burke et al.’s (2010) study of African American homicide survivors found that social support did not protect against PTSD. Although these two studies represent initial efforts to understand the relationship between social support and PTSD, clear conclusions are not possible given their conflicting findings. More studies using African American samples, particularly those based on nationally representative samples, are needed for a better understanding of the role of social support in PTSD within this population. Although little is known about the impact of social support on PTSD, especially among African Americans, a more substantive body of research has examined social support’s influence on general well-being and mental health.

Informal Support, Negative Interactions, and Mental Health among African Americans

A tradition of research demonstrates that social support promotes and protects psychological well-being and mental health. Research examining the health-related benefits of social support indicate that higher levels of emotional social support are associated with higher levels of life satisfaction (Taylor, Chatters, Hardison, & Riley, 2001) and happiness (Nguyen et al., 2015; Taylor et al., 2001) among African Americans. Additionally, social support is protective against a range of mental health problems and has been linked to lowered odds of being diagnosed with depression (Chatters et al., 2015; Lincoln & Chae, 2012; Lincoln, Taylor, Chae, & Chatters, 2010; Taylor et al., 2015), anxiety (Levine, Taylor, Nguyen, Chatters, & Himle, in press; Lincoln, Taylor, Bullard, et al., 2010), fewer depressive symptoms (Haines, Beggs, & Hurlbert, 2008; Lincoln, Chatters, & Taylor, 2005), and lower levels of psychological distress (Lincoln, Chatters, & Taylor, 2003). Conversely, African Americans experiencing low levels of social support are more likely to have suicidal ideation (Lincoln, Taylor, Chatters, & Joe, 2012; Wingate et al., 2005) and to attempt suicide (Compton, Thompson, & Kaslow, 2005; Kaslow et al., 2005; Lincoln, Taylor, Chatters, et al., 2012). More specifically, smaller social support network size and decreased frequency of contact with one’s support network are correlated with higher rates of suicide completion (Turvey et al., 2002).

Finally, although networks frequently provide social support, instances of negative interactions, while relatively infrequent (Lincoln et al., 2005; Lincoln, Taylor, & Chatters, 2012), do occur and can have deleterious effects on mental health and psychological well-being. Research exploring the harmful aspects of negative interaction on social relations indicates that individuals experiencing higher levels of negative interaction are more likely to be diagnosed with depression (Lincoln & Chae, 2012) and experience more depressive symptoms (Chatters et al., 2015; Taylor et al., 2015). High levels of negative interaction are also associated with higher risk of suicide ideation and suicide attempt (Lincoln, Taylor, Chatters, et al., 2012). Finally, with regards to well-being, higher levels of negative interaction are associated with lower levels of general psychological well-being (Nguyen et al., 2015), while lower levels of negative interaction are associated with increased resilience (Todd & Worell, 2000).

Focus of the Paper

Building upon the limited extant literature on the influence of social support and negative interaction on PTSD, the current study aims to examine the association between social support and negative interaction and 12-month PTSD among a nationally representative sample of African Americans. This study incorporates social support and relationship measures (e.g., subjective closeness, frequency of contact) for both family and friendship networks. Based on prior research, we expect that social support factors will be associated with decreased likelihood of meeting criteria for 12-month PTSD, and negative interaction with family will be positively associated with meeting criteria for 12-month PTSD. Given the scant research on this topic and the exploratory nature of this study, no specific expectations are posited for possible differential relationships between family versus friendship factors and PTSD.

This study contributes to the existing knowledge in several important ways. First, there is minimal research on PTSD using representative samples of African Americans and fewer studies have specifically examined the relation between social support and PTSD with representative samples of African Americans. The current analysis of the relationship between social support and PTSD is the first to use a national probability sample of African Americans. Second, this analysis is one of few studies that examines both family and friendship social support factors. The vast majority of research on social support among African Americans has focused exclusively on social support factors related to family. Third, although prior research indicates that social support and negative interaction co-occur within social networks, they are conceptually discrete and impact mental health in distinctive ways (Lincoln et al., 2003; Lincoln, Taylor, Chae, et al., 2010). Much of the literature in the area of social relations and PTSD has focused exclusively on social support with few studies examining negative interactions in relation to PTSD. The current study aims to bridge this gap by examining the influence of both social support and negative interaction on PTSD.

Methods

Sample

The National Survey of American Life: Coping with Stress in the 21st Century (NSAL) was collected by the Program for Research on Black Americans at the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research. The field work for the study was completed by the Institute for Social Research’s Survey Research Center, in cooperation with the Program for Research on Black Americans. The NSAL sample has a national multi-stage probability design which consists of 64 primary sampling units (PSUs). A total of 6,082 face-to-face interviews were conducted with persons aged 18 or older. This study uses the African American sub-sample of the NSAL. After listwise deletion of cases the analytic sample includes 3,315 African Americans. The use of listwise deletion in cases where missing data represents less than 10% of the sample is considered to be acceptable, having little impact on the validity of statistical inferences.

Measures

Dependent Variables

The dependent variable in this analysis is 12-month post traumatic stress disorder which was assessed using the DSM-IV World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI), a fully structured diagnostic interview. Validation studies have found that CIDI diagnoses of PTSD are concordant with independent clinical diagnoses of PTSD (Kessler & Ustün, 2004).

Independent Variables

Five independent variables representing selected measures of involvement in extended family and friendship informal social support networks were examined. Three measures assessed involvement in family support networks and two measures assessed involvement in friendship support networks. Frequency of emotional support received from family members was measured by an index of 3 items. Respondents were asked “Other than your (spouse/partner) how often do your family members: 1) make you feel loved and cared for, 2) listen to you talk about your private problems and concerns, and 3) express interest and concern in your well-being?” Response categories ranged from “very often” to “never” with higher values on this index indicating higher levels of emotional support received (M = 3.23, SE = 0.02) (Cronbach’s alpha =0.72). Frequency of having negative interactions with family members was measured also measured by an index of 3 items. Respondents were asked “Other than your (spouse/partner) how often do your family members: 1) make too many demands on you? 2) criticize you and the things you do? and 3) try to take advantage of you?” The response categories for these questions were “very often,” “fairly often,” “not too often” and “never.” Higher values on this index indicated higher levels of negative interaction with family members (M = 1.84, SE = 0.02) (Cronbach’s alpha =0.74). Frequency of contact with family members was measured by the question: “How often do you see, write or talk on the telephone with family or relatives who do not live with you? Would you say nearly everyday, at least once a week, a few times a month, at least once a month, a few times a year, hardly ever or never?” This question was also asked of friends (i.e., friend contact). Lastly, degree of subjective closeness to friends was measured by the question: “How close do you feel towards your friends? Would you say very close, fairly close, not too close or not close at all?”

Analysis Strategy

Logistic regression analysis was used and odds ratio estimates and 95% confidence intervals are presented. We present 3 logistic regression models. We estimated the association between friendship support and 12-month PTSD in Model 1. In Model 2, we tested the relationship between family support and 12-month PTSD. Finally, in Model 3, we tested the associations between friendship and family support and 12-month PTSD. Some studies have found that friendship support can offset the effects of negative family interaction on mental health and well-being (Levine et al., in press; Nguyen et al., 2015). Consequently, we tested the interactive effect of negative family interaction and subjective closeness with friends on 12-month PTSD in Model 3. All logistic regression models controlled for age, gender, marital status, education, and household income. All analyses were conducted using SAS, which uses the Taylor expansion approximation technique for calculating the complex design-based estimates of variance. Standard error estimates were corrected for unequal probabilities of selection, nonresponse, poststratification, and the sample’s complex design (i.e., clustering and stratification), and results from these analyses are generalizable to the African American adult population. Lastly, we computed the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) to check for multicollinearity between the independent variables for all of the analyses. The largest VIF was 1.56, which is far below both the threshold of 10 and the more stringent threshold of 4, which many researchers regard as a sign of severe or serious multicollinearity (O’brien, 2007).

Results

The average age of the sample was 42 years. About 40% of the sample was married, and average educational attainment was a high school education. On average, respondents reported high levels of emotional support from family and subjective closeness to friends. Respondents maintained a moderate level of contact with family and a relatively high level of contact with friends, while negative interaction with family was minimal. The bivariate analysis indicated that respondents who met criteria for 12-month PTSD differed from respondents who did not meet criteria in frequency of contact with friends, emotional support from family, negative family interaction, age, gender, education, and household income (Table 1). Respondents who met criteria for 12-month PTSD reported less frequent contact with friends, lower levels of emotional support from family, and higher levels of negative family interaction. Respondents who met criteria were also younger, more likely to be women, and had lower levels of educational attainment and household income. Respondents who met criteria for 12-month PTSD did not significantly differ from respondents who did not meet criteria in subjective closeness to friends and marital status.

Table 1.

Distribution of characteristics of African Americans in the National Survey of American Life (n = 3,315)

| 12-Month Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Test | |

| Friend Closeness, Mean (SE) | 3.17 (0.83) | 3.30 (0.77) | F = 1.51 |

| Friend Contact, Mean (SE) | 5.50 (1.85) | 5.76 (1.61) | F = 2.50* |

| Emotional Support from Family, Mean (SE) | 3.03 (0.91) | 3.26 (0.72) | F = 5.53*** |

| Family Contact, Mean (SE) | 5.94 (1.54) | 6.15 (1.26) | F = 1.17 |

| Negative Family Interaction, Mean (SE) | 2.28 (0.85) | 1.82 (0.77) | F = 4.23*** |

| Age, Mean (SE) | 37.40 (13.12) | 42.99 (16.25) | F = 1.44** |

| Gender, n (%) | χ 2 = 9.80** | ||

| Men | 26 (27.40) | 1,154 (44.80) | |

| Women | 105 (72.60) | 2,030 (55.20) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | χ 2 = 1.11 | ||

| Married | 38 (37.40) | 1,112 (42.18) | |

| Unmarried | 93 (62.60) | 2,072 (57.82) | |

| Education, Mean (SE) | 11.84 (2.50) | 12.39 (2.56) | F = 1.70* |

| Household income, Mean (SE) | 24,259.13 (31,400.82) | 32,774.64 (33,236.22) | F = 2.88** |

Note: Percentages, presented within parentheses, are weighted and frequencies are unweighted.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

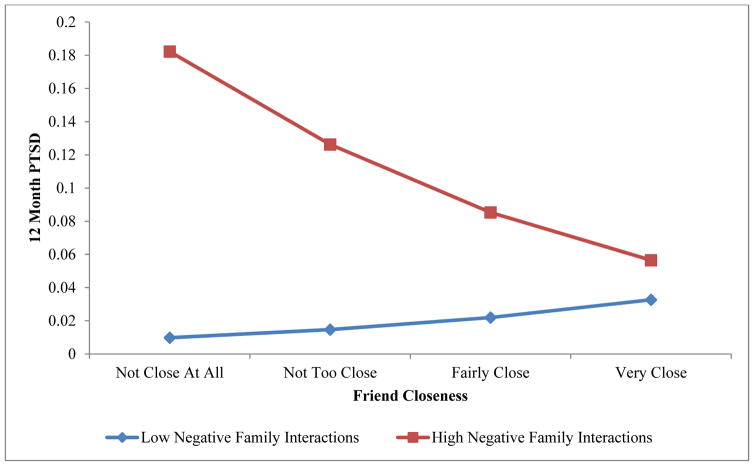

Table 2 presents the logistic regressions of 12-month PTSD on family and friendship support. In Model 1, neither subjective closeness to friends nor friend contact was associated with 12-month PTSD. Model 2 indicated that respondents who received higher levels of emotional support from family had lower odds of meeting criteria for PTSD within the past 12 months. In contrast, respondents who reported higher levels of negative interaction with family had greater odds of meeting criteria for PTSD within the past 12 months. Family contact was not significantly associated with 12-month PTSD in this model. In Model 3, with both friendship and family support assessed, emotional support from family was negatively associated with 12-month PTSD, and negative family interaction and subjective closeness to friends were positively associated with 12-month PTSD. The significant interaction between negative family interaction and subjective closeness to friends indicates that for respondents with high levels of negative interaction with their family members, the risk of meeting criteria for PTSD substantially decreases as subjective closeness to friends increases (see Figure 1). At the highest level of subjective friend closeness (“very close”), there is minimal difference in PTSD risk between persons who experience high and low negative interaction with family members. Frequency of contact with friends did not achieve significance in Model 3.

Table 2.

Multivariate weighted logistic regressions of 12-month posttraumatic stress disorder among African American respondents in the National Survey of American Life (n = 3,315)

| Model 1 OR (95% CI) |

Model 2 OR (95% CI) |

Model 3 OR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Friend Closeness | 0.92 (0.70, 1.21) | 2.02 (1.07, 3.82)* | |

| Friend Contact | 0.90 (0.77, 1.04) | 0.95 (0.80, 1.12) | |

| Negative Family Interaction * Friend Closeness | 0.75 (0.59, 0.95)* | ||

| Emotional Support from Family | 0.73 (0.55, 0.95)* | 0.71 (0.55, 0.92)** | |

| Family Contact | 0.90 (0.80, 1.02) | 0.93 (0.80, 1.07) | |

| Negative Family Interaction | 1.55 (1.20, 2.00)** | 3.87 (1.71, 8.73)** | |

| Age | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00)* | 0.99 (0.97, 1.00) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.00) |

| Gender | 2.08 (1.32, 3.27)** | 2.09 (1.26, 3.47)** | 0.69 (0.54, 0.88)** |

| Marital status (Unmarried vs. Married) | 1.03 (0.61, 1.72) | 1.10 (0.68, 1.77) | 0.96 (0.76, 1.23) |

| Education | 0.92 (0.84, 1.01) | 0.92 (0.83, 1.02) | 0. 92 (0.83, 1.01) |

| Household income | 0.97 (0.90, 1.06) | 0.98 (0.91, 1.05) | 0.98 (0.92, 1.05) |

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001; reference category for gender is male; reference category for marital status is unmarried.

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of 12 month PTSD by subjective friend closeness and negative family interaction among African Americans

Discussion

This study investigated the association between social support and 12-month PTSD among African Americans. The analysis, based on a national probability sample of African Americans, examined a range of social support factors related to family and friends, as well as negative aspects of social relations. Overall, our study found that emotional support from family was negatively associated with 12-month PTSD. This finding confirms previous studies on social support and PTSD, which found that social support protects against PTSD (Adams & Boscarino, 2006; Galea, Ahern, et al., 2002; Galea, Resnick, et al., 2002; Kilpatrick et al., 2007) and mitigates PTSD symptoms (Andrews et al., 2003; Bonanno et al., 2007; Schumm et al., 2006). Results also support and contribute to general research on social support and other mental health outcomes among African Americans. These studies verify social support’s association with lower likelihood of being diagnosed with depression (Chatters et al., 2015; Lincoln & Chae, 2012; Lincoln, Taylor, Chae, et al., 2010; Taylor et al., 2015), less severe depressive symptoms (Haines et al., 2008; Lincoln et al., 2005), decreased psychological distress (Lincoln et al., 2003), and lower odds of suicidal ideation (Lincoln, Taylor, Chatters, et al., 2012; Wingate et al., 2005), suicide attempts (Compton et al., 2005; Kaslow et al., 2005; Lincoln, Taylor, Chatters, et al., 2012), and suicide completion (Turvey et al., 2002).

Also consistent with the research on this topic, we found that negative interaction with family was positively associated with 12-month PTSD. Despite this verified link, the exact nature of the relation between negative interaction and 12-month PTSD is unclear. Because our data is cross-sectional, we are unable to determine the causal links for the relationships between PTSD and negative interactions. That is, negative interactions with family members could be both a cause and a consequence of PTSD symptoms. On the one hand, negative interactions with family members may reflect actual family situations that are characterized by chronic conflicts and difficult interpersonal relations. These family dynamics, in turn, result in emotional arousal and vigilance that trigger or heighten PTSD reactions and symptoms. Conversely, manifesting PTSD symptoms (e.g., re-experiencing trauma, emotional arousal and vigilance, avoidance and numbing) can include cognitive, emotional, and physical reactions and behaviors that lead to negative interactions with family members. Symptoms commonly present with PTSD, such as substance abuse, depression and hopelessness, and suicidal thoughts and feelings may be especially challenging for families to cope with because family members may not understand PTSD symptoms and the disorder itself is highly stigmatized and underreported (Brunet, Akerib, Birmes, Merskey, & Piper, 2007; Peters, Issakidis, Slade, & Andrews, 2006; Reardon & Factor, 2008). Family members’ attempts to be helpful in these situations may involve directive communications and motivational exhortations that emphasize the need to overcome these challenges through personal will power and effort. These messages themselves may, in effect, ‘blame the victim’ and constitute a source of further interpersonal conflict and difficulties. Similarly, it is also difficult to ascertain the nature of the association between emotional support and 12-month PTSD. It’s possible that the lack of emotional support leads to the development of or exacerbation of PTSD. Alternatively, persistent and severe PTSD symptoms may lead to diminished emotional support or ‘compassion fatigue’ among family members. Prior research suggests that the relationship between emotional support and PTSD is likely to be bidirectional (Kaniasty & Norris, 2008).

None of the friendship measures were associated with 12-month PTSD in Model 1, suggesting that social support from family had a stronger association with PTSD than support from friends. Social expectations regarding the role of kin vs. non-kin (i.e., ‘blood is thicker than water’), make it reasonable to assume that the provision of family support might be particularly beneficial for preventing the development or mitigation of symptoms of PTSD. Subjective closeness to friends, however, was important for moderating the impact of negative interaction with family members on 12-month PTSD (Model 3) and offsetting the adverse impact of negative interactions with family members on PTSD. That is, respondents in the high family negative interaction group and who had the lowest level of subjective closeness to friends were at greatest risk for PTSD. Conversely, those experiencing similarly high levels of negative interaction with family members, but who had high levels of subjective closeness to friends (very close) were comparable to persons with low levels of family negative interaction in terms of their lower risk for 12-month PTSD. These findings indicate that while family relationships play an important role in African American’s mental health and specifically, PTSD, friendships also have a distinct and complementary role. In particular, for situations involving high levels of negative interactions with family, those individuals that seek out and emotionally invest in very close friendships have lower risk of PTSD. This bears some similarity to fictive kin relationships in which friends (non-kin) are accorded the rights and statuses associated with relatives (e.g., ‘play brother or sister’) as a means by which African Americans extend kinship ties and garner additional social support from others (Taylor, Chatters, Woodward, & Brown, 2013). Although the present analysis did not assess fictive kin status, the findings clearly demonstrate the importance of friendships in terms of providing affective support that mitigate the impact of negative family dynamics on 12-month PTSD. Further, these findings underscore the importance of assessing support from both family and friends. Previous studies tended to combine multiple sources of support (e.g., family, friends, neighbors) when assessing informal support. By disaggregating various sources of support, this study provided a better understanding of the unique contributions of friendship support among African Americans.

However, the results of this study must be interpreted in relation to its limitations. The cross-sectional nature of this study does not allow for causal inferences, and longitudinal data are preferred for meaningful conclusions related to temporal and causal relationship between social support, negative interaction, and the onset of PTSD. Measures for social support and negative interaction were self-reported, which is subject to recall and social desirability biases. Further, this sample did not include institutionalized and homeless individuals, so findings cannot be generalized to these subgroups. Additionally, because the study sample is limited to non-institutionalized and non-homeless populations, the results may not reflect the full spectrum of PTSD severity, as individuals with severe mental illness are more likely to be institutionalized or homeless.

Nonetheless, the current study provides a more comprehensive picture of the relationship between social support, negative interaction and PTSD for African Americans and has several major strengths. As the first paper to examine the relation between social support and 12-month PTSD using a national probability sample of African Americans, the analysis allows us to better generalize study findings to the broader African American population. Previous studies have mainly been focused on the general population (predominately non-Hispanic white). The current analysis explored a range of social support variables that included social support factors related to both family and friendship networks. Although most studies on social support among African Americans examine social support from family, few studies include social support from friends. Moreover, we also examined negative aspects of social relations, an important but understudied facet of social relations. Negative interactions are important because they are associated with negative mental and physical health outcomes (Almeida & Horn, 2004; Newsom, Nishishiba, Morgan, & Rook, 2003; Seeman & Chen, 2002; Tanne, Goldbourt, & Medalie, 2004), produce high levels of distress for individuals (Zautra, Burleson, Matt, Roth, & Burrows, 1994), and persist over time (Bolger, DeLongis, Kessler, & Schilling, 1989). Contrary to the beneficial nature of social support, negative interactions can erode positive self-perceptions (e.g., self-esteem, competence, self-efficacy) (Krause, 2008), hinder effective coping behaviors (Lincoln, 2000) and psychological functioning (Krause, 2005; Rook, 1984), and are associated with negative affect (Newsom et al., 2003).

In terms of future research, the noted role of closeness to friends in mitigating the adverse impact of negative family interactions for 12-month PTSD suggests the need for further examination of the nature and functions of non-kin social relationships (e.g., peers, friends, fictive kin) in relation to mental health. Research on social connections and informal social supports is particularly important for African Americans and other racial and ethnic minority populations in the U.S. (Taylor et al., 2013). These groups experience higher exposures to and more serious mental health consequences resulting from trauma events that are relevant to the development of PTSD (Alim, Charney, & Mellman, 2006). Further, the risk of developing PTSD extends throughout the life course for these individuals rather than substantially decreasing after young adulthood as in the case of whites (Himle et al., 2009). Additionally, racial and ethnic minorities are typically underserved with regards to formal mental health and social services (Neighbors et al., 2007). Continuing research would better inform our understanding of the specific mental health benefits and risks associated with diverse social relationships.

Footnotes

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Ann W. Nguyen, Edward R. Roybal Institute on Aging, School of Social Work, University of Southern California, 1150 South Olive Street Suite 1400, Los Angeles, CA 90015

Linda M. Chatters, School of Public Health, School of Social Work, University of Michigan, 1415 Washington Heights, Room 3818 SPH1, Ann Arbor, MI 48109

Robert Joseph Taylor, School of Social Work, University of Michigan, 1080 South University Avenue, Room 3778 SSWB, Ann Arbor, MI 48109.

Debra Siegel Levine, VA Serious Mental Illness Treatment Resource and Evaluation Center (SMITREC), Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Joseph A. Himle, School of Social Work, University of Michigan, 1080 South University Avenue, Room 3792 SSWB, Ann Arbor, MI 48109

References

- Adams RE, Boscarino JA. Predictors of PTSD and delayed PTSD after disaster: The impact of exposure and psychosocial resources. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194(7):485–493. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000228503.95503.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alim TN, Charney DS, Mellman TA. An overview of posttraumatic stress disorder in African Americans. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62(7):801–813. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Horn MC. Is daily life more stressful during middle adulthood? In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler, editors. How healthy are we? A national study of well-being at midlife. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2004. pp. 425–451. [Google Scholar]

- Amaya-Jackson L, Davidson JR, Hughes DC, Swartz M, Reynolds V, George LK, Blazer DG. Functional impairment and utilization of services associated with posttraumatic stress in the community. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1999;12(4):709–724. doi: 10.1023/A:1024781504756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews B, Brewin CR, Rose S. Gender, social support, and PTSD in victims of violent crime. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16(4):421–427. doi: 10.1023/A:1024478305142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnberg FK, Hultman CM, Michel PO, Lundin T. Social support moderates posttraumatic stress and general distress after disaster: Buffering role of social support. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2012;25(6):721–727. doi: 10.1002/jts.21758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T. Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. Social epidemiology. 2000;1:137–173. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, DeLongis A, Kessler RC, Schilling EA. Effects of daily stress on negative mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57(5):808–818. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.57.5.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Galea S, Bucciarelli A, Vlahov D. What predicts psychological resilience after disaster? The role of demographics, resources, and life stress. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(5):671–682. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Lucia VC, Davis GC. Partial PTSD versus full PTSD: an empirical examination of associated impairment. Psychol Med. 2004;34(7):1205–1214. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet A, Akerib V, Birmes P, Merskey H, Piper A. Don’t throw out the baby with the bathwater (PTSD is not overdiagnosed) Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;52(8):501–504. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis T, Ullman SE, Tsong Y, Gobin R. Surviving the storm: The role of social support and religious coping in sexual assault recovery of African American women. Violence Against Women. 2011;17(12):1601–1618. doi: 10.1177/1077801211436138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley TC, Mozley SL, Bedard MA, Dewulf A, Greif J. Preventive health behaviors, health-risk behaviors, physical morbidity, and health-related role functioning impairment in veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Military Medicine. 2004;169(7):536–540. doi: 10.7205/milmed.169.7.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke LA, Neimeyer RA, McDevitt-Murphy ME. African american homicide bereavement: Aspects of social support that predict complicated grief, PTSD, and depression. OMEGA. 2010;61(1):1–24. doi: 10.2190/OM.61.1.a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burriss L, Ayers E, Ginsberg J, Powell DA. Learning and memory impairment in PTSD: relationship to depression. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(2):149–157. doi: 10.1002/da.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Woodward AT, Nicklett EJ. Social support from church and family members and depressive symptoms among older African Americans. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2015;23(6):559–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.04.008. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Smith PH, Thompson MP, McKeown RE, Bethea L, Davis KE. Social support protects against the negative effects of partner violence on mental health. Journal of women’s health & gender-based medicine. 2002;11(5):465–476. doi: 10.1089/15246090260137644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton MT, Thompson NJ, Kaslow NJ. Social environment factors associated with suicide attempt among low-income African Americans: the protective role of family relationships and social support. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40(3):175–185. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0865-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP. The role of adversity and stress in psychopathology: Some evidence and its implications for theory and research. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41(1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, Kilpatrick D, Bucuvalas M, Gold J, Vlahov D. Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346(13):982–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa013404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Resnick H, Ahern J, Gold J, Bucuvalas M, Kilpatrick D, … Vlahov D. Posttraumatic stress disorder in Manhattan, New York City, after the September 11th terrorist attacks. Journal of Urban Health. 2002;79(3):340–353. doi: 10.1093/jurban/79.3.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn SM, Asarnow JR, Asarnow R, Shetty V, Elliot-Brown K, Black E, Belin TR. The development of acute post-traumatic stress disorder after orofacial injury: a prospective study in a large urban hospital. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2003;61(7):785–792. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guay S, Billette V, Marchand A. Exploring the links between posttraumatic stress disorder and social support: processes and potential research avenues. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19(3):327–338. doi: 10.1002/jts.20124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines VA, Beggs JJ, Hurlbert JS. Contextualizing Health Outcomes: Do Effects of Network Structure Differ for Women and Men? Sex Roles. 2008;59(3–4):164–175. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9441-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Himle JA, Baser RE, Taylor RJ, Campbell RD, Jackson JS. Anxiety disorders among African Americans, blacks of Caribbean descent, and non-Hispanic whites in the United States. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23(5):578–590. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS. Work stress and social support. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers Inc; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Kaniasty K, Norris FH. Longitudinal linkages between perceived social support and posttraumatic stress symptoms: sequential roles of social causation and social selection. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21(3):274–281. doi: 10.1002/jts.20334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow NJ, Sherry A, Bethea K, Wyckoff S, Compton MT, Grall MB, … Thompson N. Social risk and protective factors for suicide attempts in low income African American men and women. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2005;35(4):400–412. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.4.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6) doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustün TB. The world mental health (WMH) survey initiative version of the world health organization (WHO) composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI) International journal of methods in psychiatric research. 2004;13(2):93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Koenen KC, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, Galea S, Resnick HS, … Gelernter J. The serotonin transporter genotype and social support and moderation of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in hurricane-exposed adults. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(11):1693–1699. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06122007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Negative interaction and heart disease in late life: Exploring variations by socioeconomic status. J Aging Health. 2005;17(1):28–55. doi: 10.1177/0898264304272782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Aging in the church: How social relationships affect health. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Levine DS, Taylor RJ, Nguyen AW, Chatters LM, Himle JA. Family and friendship informal support networks and social anxiety disorder among African Americans and Black Caribbeans. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1023-4. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD. Social support, negative social interactions, and psychological well-being. Social Service Review. 2000;74(2):231–252. doi: 10.1086/514478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Chae DH. Emotional support, negative interaction and major depressive disorder among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks: findings from the National Survey of American Life. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(3):361–372. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0347-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ. Psychological distress among Black and White Americans: Differential effects of social support, negative interaction and personal control. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44(3):390–407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ. Social support, traumatic events, and depressive symptoms among African Americans. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2005;67(3):754–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Bullard KM, Chatters LM, Woodward AT, Himle JA, Jackson JS. Emotional support, negative interaction and DSM IV lifetime disorders among older African Americans: findings from the National Survey of American Life (NSAL) Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(6):612–621. doi: 10.1002/gps.2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Chae DH, Chatters LM. Demographic correlates of psychological well-being and distress among older African Americans and Caribbean Black adults. Best Practices in Mental Health. 2010;6(1):103–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Correlates of emotional support and negative interaction among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks. Journal of Family Issues. 2012;34(9):1262–1290. doi: 10.1177/0192513x12454655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Joe S. Suicide, negative interaction and emotional support among black Americans. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(12):1947–1958. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0512-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors HW, Caldwell C, Williams DR, Nesse R, Taylor RJ, Bullard KMK, … Jackson JS. Race, ethnicity, and the use of services for mental disorders: Results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(4) doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.4.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsom JT, Nishishiba M, Morgan DL, Rook KS. The relative importance of three domains of positive and negative social exchanges: A longitudinal model with comparable measures. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18(4):746–754. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.4.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen AW, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Mouzon DM. Social support from family and friends and subjective well-being of older African Americans. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10902-015-9626-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’brien RM. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality & Quantity. 2007;41(5):673–690. [Google Scholar]

- Peters L, Issakidis C, Slade T, Andrews G. Gender differences in the prevalence of DSM-IV and ICD-10 PTSD. Psychol Med. 2006;36(01):81–89. doi: 10.1017/S003329170500591X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon CL, Factor RM. On-the-record screenings versus anonymous surveys in reporting PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:775. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07121960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AL, Gilman SE, Breslau J, Breslau N, Koenen KC. Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychol Med. 2011;41(1):71–83. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rook KS. The negative side of social interaction: impact on psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;46(5):1097–1108. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.46.5.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumm JA, Briggs-Phillips M, Hobfoll SE. Cumulative interpersonal traumas and social support as risk and resiliency factors in predicting PTSD and depression among inner-city women. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19(6):825–836. doi: 10.1002/jts.20159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman T, Chen X. Risk and protective factors for physical functioning in older adults with and without chronic conditions: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57(3):S135–144. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.3.s135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanne D, Goldbourt U, Medalie JH. Perceived family difficulties and prediction of 23-year stroke mortality among middle-aged men. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;18(4):277–282. doi: 10.1159/000080352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chae DH, Lincoln KD, Chatters LM. Extended family and friendship support networks are both protective and risk factors for major depressive disorder and depressive symptoms among African-Americans and Black Caribbeans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(2):132–140. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Hardison CB, Riley A. Informal Social Support Networks and Subjective Well-Being among African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology. 2001;27(4):439–463. doi: 10.1177/0095798401027004004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Woodward AT, Brown E. Racial and ethnic differences in extended family, friendship, fictive kin, and congregational informal support networks. Family Relations. 2013;62(4):609–624. doi: 10.1111/fare.12030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JL, Wilk JE, Riviere LA, McGurk D, Castro CA, Hoge CW. Prevalence of mental health problems and functional impairment among active component and National Guard soldiers 3 and 12 months following combat in Iraq. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):614–623. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd JL, Worell J. Resilience in Low-Income, Employed, African American Women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2000;24(2):119–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb00192.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turvey CL, Conwell Y, Jones MP, Phillips C, Simonsick E, Pearson JL, Wallace R. Risk factors for late-life suicide: a prospective, community-based study. American Journal of Geriatric Psych. 2002;10(4):398–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Townsend SM, Filipas HH, Starzynski LL. Structural models of the relations of assault severity, social support, avoidance coping, self-blame, and ptsd among sexual assault survivors. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31(1):23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wingate LR, Bobadilla L, Burns AB, Cukrowicz KC, Hernandez A, Ketterman RL, … Sachs-Ericsson N. Suicidality in African American men: The roles of southern residence, religiosity, and social support. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2005;35(6):615–629. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.6.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Burleson MH, Matt KS, Roth S, Burrows L. Interpersonal stress, depression, and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis patients. Health Psychology. 1994;13(2):139–148. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoellner LA, Foa EB, Brigidi BD. Interpersonal friction and PTSD in female victims of sexual and nonsexual assault. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1999;12(4):689–700. doi: 10.1023/A:1024777303848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]