Abstract

In humans, the A1 (T) allele of the dopamine (DA) D2 receptor/ankyrin repeat and kinase domain containing 1 (DRD2/ANKK1) TaqIA (rs1800497) single nucleotide polymorphism has been associated with reduced striatal DA D2/D3 receptor (D2/D3R) availability. However, radioligands used to estimate D2/D3R are displaceable by endogenous DA and are non-selective for D2R, leaving the relationship between TaqIA genotype and D2R specific binding uncertain. Using the positron emission tomography (PET) radioligand, (N‐[11C]methyl)benperidol ([11C]NMB), which is highly selective for D2R over D3R and is not displaceable by endogenous DA, the current study examined whether DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA genotype predicts D2R specific binding in 2 independent samples. Sample 1 (n = 39) was composed of obese and non-obese adults; sample 2 (n = 18) was composed of healthy controls, unmedicated individuals with schizophrenia, and siblings of individuals with schizophrenia. Across both samples, A1 allele carriers (A1+) had 5-12% less striatal D2R specific binding relative to individuals homozygous for the A2 allele (A1−), regardless of body mass index or diagnostic group. This reduction is comparable to previous PET studies of D2/D3R availability (10-14%). The pooled effect size for the difference in total striatal D2R binding between A1+ and A1− was large (0.84). In summary, in line with studies using displaceable D2/D3R radioligands, our results indicate that DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA allele status predicts striatal D2R specific binding as measured by D2R-selective [11C]NMB. These findings support the hypothesis that DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA allele status may modify D2R, perhaps conferring risk for certain disease states.

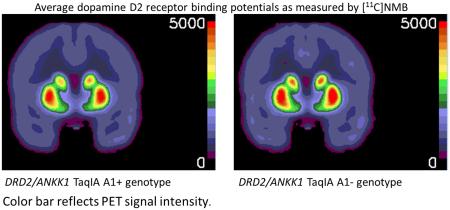

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

We investigated the difference in striatal dopamine D2 receptor binding, as measured by PET with (N-[11C]methyl)benperidol ([11C]NMB), between A1 allele carriers (A1+) and individuals homozygous for the A2 allele (A1−) of the DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA single nucleotide polymorphism. In Study 1, A1+ had 5-12% less striatal [11C]NMB binding than A1−.

Keywords: rs1800497, PET, dopamine

Introduction

The role of striatal dopamine (DA) signaling in substance abuse and psychiatric disorders has yet to be fully characterized. Postiron emission tomography (PET) studies with displaceable DA D2/D3 receptor (D2/D3R) radioligands show that low striatal D2/D3R availability may be associated with impulsivity (Clark et al., 2012), addiction to alcohol (Volkow et al., 1996; Martinez et al., 2005), substance abuse (Volkow et al., 1990; Volkow et al., 2001; Martinez et al., 2004; Fehr et al., 2008), and obesity (Wang et al., 2001; Haltia et al., 2007; de Weijer et al., 2011) whereas high D2/D3R availability has been associated with risk for schizophrenia (Laruelle, 1998), although this finding has not been replicated (Howes et al., 2012; Kambeitz et al., 2014). Similarly, the A1 (T) allele of the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) TaqIA (rs1800497), located in the ankyrin repeat and kinase domain containing 1 (ANKK1) 10 kb downstream from the DA D2 receptor (DRD2) gene (Grandy et al., 1989), is associated with addictive behavior including gambling (Comings et al., 1996), substance abuse (Noble et al., 1993; Persico et al., 1996; Lawford et al., 2000; Chen et al., 2004; Messas et al., 2005), and binge eating (Davis et al., 2012) and with obesity (Noble et al., 1994; Spitz MR, 2000; Thomas et al., 2001; Stice et al., 2008; Duran-Gonzalez et al., 2011) while the A2 (C) allele is associated with risk for schizophrenia (Parsons et al., 2007; Dubertret et al., 2010; Arab and Elhawary, 2015).

Individual variability in striatal D2/D3R availability is significantly heritable, as detected by a twin study (Borg et al., 2015). In addition, the similar pattern of associations between DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA variants and D2/D3R availability with psychiatric and drug abuse risk has led to speculation that DRD2’s role in these disorders may be mediated by D2R. Indeed, the A1 allele of the DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA A1 variant has been associated with lower striatal D2/D3R availability relative to the A2 allele in several postmortem (Noble et al., 1991; Thompson et al., 1997; Ritchie and Noble, 2003; Gluskin and Mickey, 2016) and in vivo PET studies (Pohjalainen et al., 1998; Jonsson et al., 1999; Hirvonen et al., 2009a; Savitz et al., 2013; Gluskin and Mickey, 2016). However, a SPECT study (Laruelle et al., 1998) and two PET studies (Brody et al., 2006; Wagner et al., 2014) did not find this association, likely due to study of diseased populations (Gluskin and Mickey, 2016). To date, studies have used PET radioligands (e.g. [11C]raclopride (Thompson et al., 1997; Pohjalainen et al., 1998; Jonsson et al., 1999; Brody et al., 2006; Hirvonen et al., 2009a; Savitz et al., 2013; Wagner et al., 2014), [3H]spiperone (Noble et al., 1991; Ritchie and Noble, 2003)) and the SPECT radioligand [123I]IBZM (Laruelle et al., 1998), which do not discriminate between D2R and D3R and whose binding is affected by synaptic dopamine concentrations, leaving the link between DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA genotype and D2R specific binding unclear. The novel PET radioligand (N-[11C]methyl)benperidol ([11C]NMB) specifically binds to D2R in a reversible manner, does not undergo agonist-mediated internalization, is resistant to displacement by endogenous DA, and is selective for D2R over D3R by 200-fold (Moerlein et al., 1997; Karimi et al., 2011). Thus, [11C]NMB is an ideal radioligand to use for the study of D2R binding under various conditions including disease states and genotype status.

The current studies examined whether DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA allele status is associated with striatal D2R specific binding. We analyzed data from two independent studies that employed PET with [11C]NMB and included human participants genotyped for the DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA variant. Based on previous evidence (Pohjalainen et al., 1998; Jonsson et al., 1999; Savitz et al., 2013; Gluskin and Mickey, 2016), we hypothesized that A1 allele carriers (A1+) would have lower striatal D2R binding than individuals homozygous for A2 (A1−). We also performed meta-analyses to generate pooled effect sizes that reflect the ability of DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA allele status to predict D2R specific binding across striatal regions.

Materials and Methods

Participants

For Study 1, participants were recruited for a study of obesity and D2R from the St. Louis region via a research volunteer database, flyers, and word of mouth. Data from these individuals regarding the relationship between obesity and striatal D2R were previously presented (Eisenstein et al., 2013; Eisenstein et al., 2015b; Eisenstein et al., 2015a). Obese (n = 24) and non-obese (n = 20) individuals, aged 18-40 years, were eligible for the study based on strict inclusion and exclusion criteria (Eisenstein et al., 2013). Exclusion criteria included a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes (based on oral glucose tolerance test), history of psychiatric or neurological diagnoses, tobacco or illegal substance use, and dopaminergic medication use. Handedness was obtained by self-report. A subset of participants (24 obese and 16 non-obese) were genotyped for the DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA (rs1800497) polymorphism and completed PET neuroimaging. Some participants were not genotyped because we did not have biological specimens from which to extract DNA (n = 4).

For Study 2, healthy controls (HC; n = 10), siblings of individuals with schizophrenia (SIB; n = 10), and individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (SCZ; n = 3) were recruited for a study of schizophrenia, reward behavior, and D2R. Participants (age range 18-50 years) were recruited by word of mouth, flyers, and during recruiting visits to clinics and mental health centers in St. Louis, MO. A trained research assistant administered the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV(First et al., 2002) to all participants to determine the lifetime and current history of Axis I disorders. Exclusionary criteria included DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence, either currently or within the last 6 months; neurological disorder; history of concussion or head injury; pregnancy; claustrophobia; presence in body of non-removable metallic objects or implanted medical electronic devices; mental retardation; positive drug urine test; and positive alcohol breathalyzer reading. HC must not have had lifetime or family history of psychotic disorders; current mood or anxiety disorder except for specific phobia but may have had a past Axis I disorder except for a psychotic disorder. The exclusionary criteria for SIB were identical to that of HC except that the participant must have had a sibling with confirmed diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. SIB were unrelated to SCZ who completed this study. SCZ must have met DSM-IV criteria for diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Participants must have voluntarily abstained from medications such as DA agonists and antagonists and other psychotropic drugs for at least 4 weeks. During each study visit, evidence of alcohol use during the last 24 hr and recent use of drugs of abuse was obtained by breathalyzer and from urine sample drug test, respectively. Handedness was obtained by self-reported preferred hand for writing. A total of 8 HC, 8 SIB, and 2 SCZ were genotyped for the DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA (rs1800497) polymorphism and completed PET neuroimaging. Some participants were not genotyped because they participated in the study after genotyping was carried out (n = 2) or we did not have biological specimens from which to extract DNA (n = 3).

Participants in both studies provided written informed consent prior to participation. The study protocols were approved by the Washington University School of Medicine (WUSM) Human Research Protection Office and the Radioactive Drug Research Committee, and carried out in accordance with the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki.

DNA Extraction and Genotyping

Blood (Study 1) and saliva (Study 2) were obtained from participants and DNA was extracted. Participants were genotyped for the DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA (rs1800497) polymorphism (A1/A2; T/C) by the Sequenom Technology Core at WUSM, the Molecular Psychiatry Core, and the Adipocyte Biology and Molecular Nutrition Core at WUSM using mass-spectrometry (Study 1), pyrosequencing (Study 1 and Study 2), and a pre-designed Taqman SNP genotyping assay (Study 1; Applied Biosystems; Waltham, MA), respectively. Subjects were categorized as A1 allele carriers (A1+) or A2 allele homozygotes (A1−).

Magnetic resonance imaging and PET Imaging

For Study 1, the methods used to obtain magnetic resonance image (MRI) and PET scans were reported (Eisenstein et al., 2013). Briefly, MRI scans were obtained on the Siemens MAGNETOM Tim Trio 3T using a 3-D MP-RAGE sequence (sagittal orientation, TR = 2400 ms, TE = 3.16 ms, flip angle = 8 degrees, slab thickness = 176 mm, FOV = 256 × 256 mm, voxel dimensions = 1 ×1 × 1 mm) and PET scans were obtained on the Siemens CTI ECAT/EXACT HR+. The radioligand [11C]NMB was prepared using an automated system previously described (Moerlein et al., 2004; Moerlein et al., 2010). Radiochemical purity of [11C]NMB was ≥ 96% and specific activity was ≥ 1000 Ci/mmol (39 TBq/mmol). Participants received 6.4-18.1 mCi [11C]NMB intravenously.

For Study 2, structural magnetic resonance T1-weighted anatomical images were obtained with the Siemens Biograph mMR PET/MR scanner using a 3-D MP-RAGE sequence (sagittal orientation, TR=2400 ms, TE=2.67 ms, flip angle=7 degrees, slab thickness=192 mm, FOV=256×256 mm; voxel dimensions= 1×1×1 mm). PET images were acquired simultaneously with the radioligand [11C]NMB. [11C]NMB was prepared as described for Study 1. Radiochemical purity of [11C]NMB was ≥ 95% and specific activity was ≥ 1000 Ci/mmol (36 TBq/mmol). Participants received 5.9-18.8 mCi [11C]NMB intravenously.

MR and PET image processing has been previously described in detail (Eisenstein et al., 2012; Eisenstein et al., 2013). A priori regions of interest (ROIs) including dorsal and ventral areas of the striatum (putamen, caudate, and nucleus accumbens (NAc)) were identified using FreeSurfer (Fischl et al., 2002) on the MP-RAGE MR images for each participant. Dynamic PET images were co-registered to each other and to the MP-RAGE image for each individual as previously described (Eisenstein et al., 2012). ROIs and the cerebellar reference region were resampled in the same atlas space and decay-corrected tissue activity curves were obtained from the dynamic PET data for every ROI. For both studies, a priori regions of interest (ROIs) included putamen, caudate, nucleus accumbens (NAc), dorsal striatum (putamen + caudate), and total striatum (putamen + caudate + NAc). D2R non-displaceable binding potentials (BPNDs) were obtained for each ROI with the Logan graphical method with whole cerebellum as a reference region (Antenor-Dorsey et al., 2008). D2R BPNDs for each ROI were averaged across left and right hemispheres to reduce the number of comparisons for primary analyses and because we did not have a priori hypotheses about laterality effects.

Meta-analyses

Cohen’s d effect sizes were estimated for Study 1 and Study 2. To obtain pooled effect sizes for differences in D2R specific binding between A1+ and A1−, meta-analyses were performed including Study 1 and Study 2 for each ROI.

Primary Statistical Analyses

Data from each study was analyzed separately due to use of different PET scanners Hierarchical linear regressions were used to determine whether DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA allele status predicted D2R BPND for each ROI. Step 1 included covariates age, education level, ethnicity (White vs. not), and gender and Step 2 included group (obese vs non-obese or HC vs SIB vs SCZ). Step 3 included allele status (A1+ vs A1−) and Step 4 included the interaction between group and allele status. We calculated BPND means for each ROI adjusted for age, education level, ethnicity, gender and diagnostic group. We then calculated the percent difference in D2R BPND between A1+ vs A1− groups. Cohen’s d effect sizes for each study were calculated using means and standard deviations and number of individuals in each allele group (A1+ and A1−). Meta-analyses were performed with Revman 5.3 software (Cochrane IMS, Oxford, UK). Weighted mean difference (MD) with the corresponding 95% CI was reported as the pooled effect size. I2 and χ2 tests determined heterogeneity and p < 0.10 was considered significant. Since heterogeneity did not exist across studies (I2 ≤ 54%, p ≥ 0.14), a fixed-effects model was used to calculate pooled effect size. Forest plots were generated with p < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Participants

In Study 1, 40 individuals were genotyped for the DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA (rs1800497) polymorphism. For unknown reasons, one obese, A1/A2 participant’s D2R binding values were greater than 2.5 (2.55-3.14 across all ROIs) standard deviations above the A1+ group mean and was thus excluded from analyses. Only one individual was homozygous for the A1 allele. Therefore, this participant’s data was pooled with that from A1/A2 individuals for comparisons to individuals homozygous for A2. The final dataset included 14 obese and 7 non-obese A1+ and 9 obese and 9 non-obese A1−. The distributions of obese and non-obese were not different between A1+ and A1− (χ2 = 1.11, p = 0.29). Handedness distribution did not differ between A1+ and A1− (χ2 = 1.81, p = 0.18). Participant demographics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics for Studies 1 and 2. Mean (S.D.) shown.

| Study 1 | |||

| Non-obese (n = 16) |

Obese (n = 23) |

||

| Age (years) | 28.8 (5.6) | 32.3 (6.2) | |

| Education (years) |

16.2 (1.4) | 15.0 (1.9) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.2 (2.1) | 40.2 (4.9) | |

| Gender | 11 F/5 M | 19 F/ 4 M | |

| Ethnicity | 13 Caucasian, 1 African American, 1 Hispanic, 1 Other |

12 Caucasian, 11 African American |

|

| Handedness | 14 right, 2 non-right | 23 right | |

| Allele distribution |

7 A1/A2, 9 A2/A2 | 1 A1/A1, 13 A1/A2, 9 A2/A2 |

|

| Study 2 | |||

| Healthy Control (n = 8) |

Sibling (n = 8) |

Schizophrenia (n = 2) |

|

| Age (years) | 35.5 (10.3) | 33.3 (7.6) | 36 (5.7) |

| Education (years) |

12.6 (1.5) | 14.9 (1.6) | 12.5 (0.7) |

| Gender | 3 F/5 M | 5 F/3 M | 1 F/1 M |

| Ethnicity | 4 Caucasian, 4 African American | 5 Caucasian, 3 African American |

2 African American |

| Handedness | 6 right, 2 non-right | 7 right, 1 non-right | 1 right, 1 non- right |

| Allele distribution |

6 A1/A2; 2 A2/A2 | 3 A1/A2, 5 A2/A2 | 2 A2/A2 |

In Study 2, 8 HC, 8 SIB, and 2 unmedicated SCZ were genotyped for the DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA (rs1800497) polymorphism and had PET D2R binding data. At the PET imaging visit, SCZ had not taken antipsychotic medications for ≥ 9 months and did not display overt signs of psychopathology. There were no individuals homozygous for the A1 allele. 6 HC and 3 SIB were A1+ and 2 HC, 5 SIB, and 2 SCZ were A1−. Group distribution was not different between A1+ and A1− (χ2 = 4.50, p = 0.11). Handedness distribution did not differ between A1+ and A1− (χ2 = 0, p = 1). Participant demographics are presented in Table 1.

Genotyping Quality Control

Across both studies DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA genotype did not deviate from Hardy-Weinburg Equilibrium in either sample (Study 1: χ2 = 2.8, p = 0.10; Study 2: χ2 = 2.0, p = 0.16) or within the African American (AA) and Caucasian (C) subsamples (AA, Study 1: χ2 = 3.0, p = 0.08; Study 2: χ2 = 1.3, p = 0.25; C, Study 1: χ2 = 0.9, p = 0.34; Study 2: χ2 = 0.7, p = 0.39). Distribution of allele frequencies did not differ between AA and- C in either study (Study 1: χ2 = 0.71, p = 0.40; Study 2: χ2 = 0.22, p = 0.64) or among groups (obese/non-obese or HC/SIB/SCZ) across either study (Study 1: χ2 = 1.1, p = 0.29; Study 2: χ2 = 4.5, p = 0.11).

Prediction of Striatal D2R Binding by DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA Allele Status

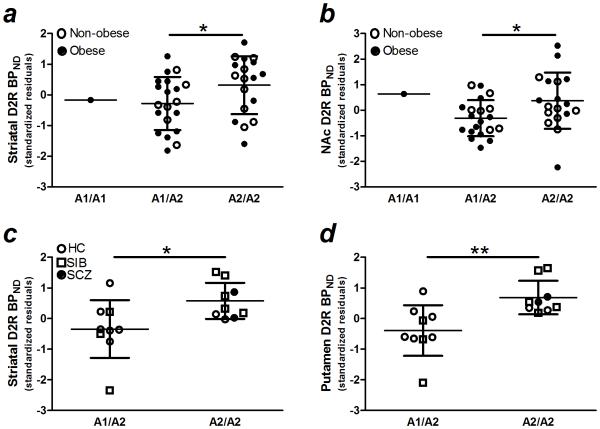

In Study 1, DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA allele status predicted D2R binding in total striatum and nucleus accumbens (both β ≥ 0.29, p ≤ 0.05; both ΔR2 ≥ 0.07; Fig 1a-b,Table 2) and in dorsal striatum at trend-level significance (p = 0.09, Table 2). DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA allele status and D2R binding in putamen and caudate were not significantly related (both β ≤ 0.23, p = 0.11, Table 2). Across ROIs, D2R binding was lower in A1+ relative to A1− by 5-8%). Neither a main effect of obesity group (obese/non-obese) nor an interactive effect with DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA allele status was observed for D2R binding in any ROI (all p ≥ 0.13, Table 2). D2R BPND means (S.D.s), percent difference in binding, and estimated Cohen’s d effect sizes are presented in Table 3.

Figure 1.

In Study 1, DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA (rs1800497) allele status predicted D2R specific binding in a) striatum (putamen + caudate + nucleus accumbens) and b) nucleus accumbens. The data from the A1/A1 individual was pooled with data from A1/A2 for statistical analysis. In Study 2, DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA (rs1800497) allele status predicted D2R specific binding in c) striatum and d) putamen. D2R BPND, dopamine D2 receptor non-displaceable binding potential; NAc, nucleus accumbens; HC, healthy control; SIB, sibling of individual with schizophrenia; SCZ, individual with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. *, **, p ≤ 0.05, = 0.01

Table 2.

Summary of hierarchical multiple linear regression analyses for prediction of striatal dopamine D2 receptor specific binding by DRD2/ANKK1 Taq1A (rs1800497) allele status in Study 1.

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Striatum (N = 39) | ||||||||||||

| Variable | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β |

| Education | .14 | .10 | .21 | .16 | .11 | .24 | .16 | .10 | .25 | .16 | .10 | .25 |

| Age | −.07 | .03 | −.37 | −.08 | .03 | −.39 | −.08 | .03 | −.42 | −.08 | .03 | −.42 |

| Gender | .59 | .39 | .21 | .54 | .40 | .19 | .27 | .40 | .10 | .27 | .42 | .10 |

| White or not | .44 | .35 | .18 | .49 | .36 | .20 | .46 | .34 | .19 | .46 | .36 | .19 |

| Group | −.25 | .37 | −.10 | −.42 | .36 | −.18 | −.44 | 1.1 | −.19 | |||

| Allele status | .68 | .33 | .29* | .66 | 1.0 | .28 | ||||||

| Group × allele status | .01 | .69 | .01 | |||||||||

| R2 | .38 | .39 | .46 | .46 | ||||||||

|

F for change in R2 |

5.2, p < 0.01 | 0.45, p = 0.51 | 4.3, p = 0.05 | 0, p = 0.98 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Dorsal Striatum (N = 39) | ||||||||||||

| Variable | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β |

| Education | .10 | .09 | .18 | .12 | .09 | .21 | .12 | .09 | .22 | .12 | .09 | .22 |

| Age | −.06 | .03 | −.35 | −.06 | .03 | −.38 | −.07 | .03 | −.40 | −.07 | .03 | −.41 |

| Gender | .42 | .34 | .18 | .36 | .35 | .15 | .16 | .36 | .07 | .13 | .37 | .06 |

| White or not | .37 | .31 | .18 | .42 | .31 | .21 | .40 | .31 | .19 | .44 | .32 | ..21 |

| Group | −.27 | .32 | −.13 | −.40 | .32 | −.20 | −.81 | 1.0 | −.40 | |||

| Allele status | .51 | .29 | .26† | .15 | .90 | .08 | ||||||

| Group × allele status | .26 | .61 | .30 | |||||||||

| R2 | .32 | .33 | .39 | .39 | ||||||||

|

F for change in R2 |

4.0, p = 0.01 | 0.67, p = 0.42 | 3.1, p = 0.09 | 0.18, p = 0.67 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Putamen (N = 39) | ||||||||||||

| Variable | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β |

| Education | .03 | .04 | .10 | .04 | .04 | .15 | .04 | .04 | .16 | .04 | .04 | .16 |

| Age | −.04 | .01 | −.47 | −.04 | .01 | −.50 | −.04 | .01 | −.52 | −.04 | .01 | −.52 |

| Gender | .27 | .16 | .24 | .23 | .16 | .20 | .14 | .17 | .13 | .13 | .17 | .11 |

| White or not | .11 | .14 | .11 | .15 | .14 | .15 | .14 | .14 | .14 | .15 | .15 | .15 |

| Group | −.18 | .15 | −.18 | −.23 | .15 | −.24 | −.43 | .46 | −.44 | |||

| Allele status | .22 | .14 | .23 | .05 | .41 | .05 | ||||||

| Group × allele status | .12 | .28 | .29 | |||||||||

| R2 | .38 | .40 | .45 | .46 | ||||||||

|

F for change in R2 |

5.2, p < 0.01 | 1.4, p = 0.25 | 2.8, p = 0.11 | 0.20, p = 0.66 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Caudate (N = 39) | ||||||||||||

| Variable | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β |

| Education | .07 | .06 | .22 | .08 | .06 | .24 | .08 | .06 | .25 | .08 | .26 | .25 |

| Age | −.02 | .02 | −.23 | −.02 | .02 | −.24 | −.03 | .02 | −.27 | −.03 | .02 | −.27 |

| Gender | .15 | .21 | .11 | .13 | .21 | .10 | .02 | .22 | .01 | 0 | .23 | 0 |

| White or not | .26 | .18 | .22 | .28 | .19 | .24 | .26 | .19 | .22 | .28 | .20 | .24 |

| Group | −.09 | .20 | −.08 | −.17 | .20 | −.15 | −.38 | .62 | −.33 | |||

| Allele status | .29 | .18 | .26 | .10 | .55 | .09 | ||||||

| Group × allele status | .14 | .37 | .28 | |||||||||

| R2 | .24 | .25 | .31 | .31 | ||||||||

|

F for change in R2 |

2.7, p = 0.04 | 0.22, p = 0.64 | 2.6, p =.11 | 0.14, p = .71 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Nucleus Accumbens (N = 39) | ||||||||||||

| Variable | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β |

| Education | .04 | .03 | .27 | .04 | .03 | .26 | .04 | .03 | .28 | .04 | .02 | .27 |

| Age | −.01 | .01 | −.30 | −.01 | .01 | −.29 | −.02 | .01 | −.32 | −.02 | .01 | −.31 |

| Gender | .17 | .09 | .26 | .18 | .10 | .27 | .11 | .10 | .17 | .14 | .10 | .21 |

| White or not | .07 | .08 | .13 | .07 | .09 | .12 | .06 | .08 | .11 | .03 | .08 | .05 |

| Group | .02 | .09 | .03 | −.02 | .09 | −.04 | .37 | .26 | .64 | |||

| Allele status | .17 | .08 | .30* | .51 | .23 | .91 | ||||||

| Group × allele status | −.25 | .16 | −1.0 | |||||||||

| R2 | .37 | .37 | .45 | .49 | ||||||||

|

F for change in R2 |

5.0, p < 0.01 | 0.1, p = 0.83 | 4.5, p = 0.04 | 2.4, p = 0.13 | ||||||||

, p ≤ 0.05;

, p = 0.09

Table 3.

Mean (S.D.) striatal D2 receptor specific binding (BPND) by DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA allele status.

| N | BPND

Unadjusted |

BPND

Adjusted |

Percent difference in Adjusted BPND between A1+ and A1− |

Estimated Effect Size (Cohen’s d) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | |||||

| Total Striatum | |||||

| Total Sample | |||||

| A1+ | 21 | 9.74 (0.80) | 9.75 (0.99) | 6.5% | 0.69 |

| A1− | 18 | 10.45 (1.46) | 10.43 (0.99) | ||

| Non-obese | |||||

| A1+ | 7 | 9.92 (0.86) | |||

| A1− | 9 | 10.47 (1.53) | |||

| Obese | |||||

| A1+ | 14 | 9.65 (0.79) | |||

| A1− | 9 | 10.43 (1.48) | |||

| Dorsal Striatum | |||||

| Total Sample | |||||

| A1+ | 21 | 7.81 (0.70) | 7.81 (0.88) | 6.1% | 0.58 |

| A1− | 18 | 8.32 (1.23) | 8.32 (0.89) | ||

| Non-obese | |||||

| A1+ | 7 | 7.86 (0.69) | |||

| A1− | 9 | 8.36 (1.28) | |||

| Obese | |||||

| A1+ | 14 | 7.78 (0.72) | |||

| A1− | 9 | 8.28 (1.26) | |||

| Putamen | |||||

| Total Sample | |||||

| A1+ | 21 | 4.02 (0.35) | 4.02 (0.40) | 5.2% | 0.54 |

| A1− | 18 | 4.24 (0.59) | 4.24 (0.41) | ||

| Non-obese | |||||

| A1+ | 7 | 3.98 (0.28) | |||

| A1− | 9 | 4.25 (0.68) | |||

| Obese | |||||

| A1+ | 14 | 4.03 (0.39) | |||

| A1− | 9 | 4.23 (0.54) | |||

| Caudate | |||||

| Total Sample | |||||

| A1+ | 21 | 3.79 (0.41) | 3.79 (0.54) | 7.1% | 0.54 |

| A1− | 18 | 4.08 (0.70) | 4.08 (0.54) | ||

| Non-obese | |||||

| A1+ | 7 | 3.87 (0.43) | |||

| A1− | 9 | 4.12 (0.65) | |||

| Obese | |||||

| A1+ | 14 | 3.75 (0.40) | |||

| A1− | 9 | 4.05 (0.78) | |||

| Nucleus Accumbens | |||||

| Total Sample | |||||

| A1+ | 21 | 1.93 (0.21) | 1.94 (0.24) | 8.1% | 0.71 |

| A1− | 18 | 2.13 (0.32) | 2.11 (0.24) | ||

| Non-obese | |||||

| A1+ | 7 | 1.86 (0.07) | |||

| A1− | 9 | 2.15 (0.09) | |||

| Obese | |||||

| A1+ | 14 | 1.86 (0.20) | |||

| A1− | 9 | 2.14 (0.39) | |||

| Study 2 | |||||

| Total Striatum | |||||

| Total Sample | |||||

| A1+ | 9 | 10.66 (1.70) | 10.48 (1.1) | 10.7% | 1.14 |

| A1− | 9 | 11.54 (1.40) | 11.73 (1.1) | ||

| Healthy Control | |||||

| A1+ | 6 | 10.87 (1.74) | |||

| A1− | 2 | 10.04 (1.51) | |||

| Sibling | |||||

| A1+ | 3 | 10.26 (1.81) | |||

| A1− | 5 | 12.24 (1.18) | |||

| Schizophrenia | |||||

| A1+ | 0 | N/A | |||

| A1− | 2 | 11.31 (0.66) | |||

| Dorsal Striatum | |||||

| Total Sample | |||||

| A1+ | 9 | 7.62 (1.2) | 7.48 (0.79) | 11.7% | 1.25 |

| A1− | 9 | 8.33 (0.95) | 8.47 (0.79) | ||

| Healthy Control | |||||

| A1+ | 6 | 7.75 (1.27) | |||

| A1− | 2 | 7.37 (1.11) | |||

| Sibling | |||||

| A1+ | 3 | 7.35 (1.4) | |||

| A1− | 5 | 8.77 (0.85) | |||

| Schizophrenia | |||||

| A1+ | 0 | N/A | |||

| A1− | 2 | 8.20 (0.55) | |||

| Putamen | |||||

| Total | |||||

| Sample | |||||

| A1+ | 9 | 4.19 (0.57) | 4.07 (0.33) | 11.3% | 1.56 |

| A1− | 9 | 4.47 (0.5) | 4.59 (0.33) | ||

| Healthy Control | |||||

| A1+ | 6 | 4.31 (0.58) | |||

| A1− | 2 | 4.09 (0.61) | |||

| Sibling | |||||

| A1+ | 3 | 3.94 (0.58) | |||

| A1− | 5 | 4.67 (0.47) | |||

| Schizophrenia | |||||

| A1+ | 0 | N/A | |||

| A1− | 2 | 4.33 (0.43) | |||

| Caudate | |||||

| Total | |||||

| Sample | |||||

| A1+ | 9 | 3.43 (0.70) | 3.41 (0.5) | 12.1% | 0.94 |

| A1− | 9 | 3.87 (0.48) | 3.88 (0.5) | ||

| Healthy Control | |||||

| A1+ | 6 | 3.44 (0.72) | |||

| A1− | 2 | 3.29 (0.5) | |||

| Sibling | |||||

| A1+ | 3 | 3.41 (0.84) | |||

| A1− | 5 | 4.10 (0.4) | |||

| Schizophrenia | |||||

| A1+ | 0 | N/A | |||

| A1− | 2 | 3.87 (0.12) | |||

| Nucleus Accumbens | |||||

| Total Sample | |||||

| A1+ | 9 | 3.05 (0.45) | 3.0 (0.32) | 8.0% | 0.81 |

| A1− | 9 | 3.21 (0.45) | 3.26 (0.32) | ||

| Healthy Control | |||||

| A1+ | 6 | 3.11 (0.48) | |||

| A1− | 2 | 2.67 (0.39) | |||

| Sibling | |||||

| A1+ | 3 | 2.91 (0.44) | |||

| A1− | 5 | 3.47 (0.35) | |||

| Schizophrenia | |||||

| A1+ | 0 | N/A | |||

| A1− | 2 | 3.10 (0.11) | |||

BPND, non-displaceable binding potential; A1+, DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA (rs1800497) A1 allele carrier; A1−, DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA (rs1800497) A2 allele homozygote; N/A, not applicable.

BPND adjusted means are adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, education, and group membership.

In Study 2, DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA allele status predicted D2R binding in total striatum, dorsal striatum, and putamen (all β ≥ 0.41, p ≤ 0.05; all R2 ≥ 0.11; Fig 1c-d,Table 4). DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA allele status did not significantly predict caudate or NAc D2R binding (both p ≥ 0.09,Table 4). Across all ROIs, D2R binding was lower in A1+ relative to A1− by 8-12%. Diagnostic group (HC, SCZ, SIB) did not significantly predict D2R binding in any ROI (all p ≥ 0.13) but the relationship was near significant for caudate (p = 0.07), in which SIB (mean BPND (S.D.) = 3.8 (0.6)) and SCZ (mean BPND (S.D.) = 3.9 (0.1)) tended to have greater D2R binding relative to HC (mean BPND (S.D.) = 3.4 (0.6)). It should be noted, however, that SCZ had a small sample size (n = 2). Group and DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA allele status did not interact to affect D2R binding in any ROI (all p ≥ 0.44). D2R BPND means (S.D.s), percent difference in binding, and estimated Cohen’s d effect sizes are presented in Table 3.

Table 4.

Summary of hierarchical multiple linear regression analyses for prediction of striatal D2R specific binding by DRD2/ANKK1 Taq1A (rs1800497) allele status in Study 2.

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Striatum (N = 18) | ||||||||||||

| Variable | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β |

| Education | −.20 | .18 | −.24 | −.28 | .18 | −.33 | −.37 | .16 | −.44 | −.28 | .21 | −.34 |

| Age | −.06 | .04 | −.31 | −.05 | .04 | −.27 | −.06 | .03 | −.29 | −.06 | .03 | −.34 |

| Gender | 1.8 | .72 | .58 | 1.8 | .67 | .61 | 2.2 | .60 | .72 | 1.9 | .70 | .64 |

| White or not | 1.7 | .62 | .55 | 1.9 | .60 | .62 | 1.7 | .52 | .57 | 1.7 | .55 | .55 |

| Group | .67 | .41 | .29 | .20 | .41 | .09 | .05 | .48 | .02 | |||

| Allele status | 2.5 | 1.1 | .41* | .15 | 3.8 | .03 | ||||||

| Group × allele status | 1.4 | 2.2 | .42 | |||||||||

| R2 | .58 | .66 | .77 | .78 | ||||||||

|

F for change in R2 |

4.6 | 4.6, p = 0.02 | 2.7, p = 0.13 | 5.1, p = 0.05 | 0.42, p = 0.53 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Dorsal Striatum (N = 18) | ||||||||||||

| Variable | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β |

| Education | −.13 | .14 | −.21 | −.19 | .14 | −.31 | −.26 | .12 | −.43 | −.21 | .16 | −.34 |

| Age | −.05 | .03 | −.33 | −.04 | .03 | −.29 | −.04 | .02 | −.32 | −.05 | .03 | −.36 |

| Gender | 1.2 | .54 | .53 | 1.2 | .51 | .55 | 1.5 | .45 | .67 | 1.3 | .53 | .61 |

| White or not | 1.2 | .47 | .52 | 1.3 | .45 | .59 | 1.2 | .39 | .54 | 1.1 | .41 | .52 |

| Group | .50 | .31 | .30 | .13 | .30 | .08 | .03 | .36 | .02 | |||

| Allele status | 2.0 | .82 | .45* | .51 | 2.8 | .12 | ||||||

| Group × allele status | .89 | 1.6 | .36 | |||||||||

| R2 | .55 | .63 | .76 | .77 | ||||||||

|

F for change in R2 |

4.0 | , p = 0.03 | 2.6, p = 0.13 | 5.8, p = 0.04 | .30, p = 0.60 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Putamen (N = 18) | ||||||||||||

| Variable | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | p | B | SE B | β |

| Education | −.10 | .06 | −.33 | −.11 | .06 | −.39 | −.15 | .05 | −.52 | −.12 | .07 | −.40 |

| Age | −.02 | .01 | −.35 | −.02 | .01 | −.33 | −.02 | .01 | −.36 | −.03 | .01 | −.41 |

| Gender | .59 | .24 | .56 | .61 | .24 | .58 | .74 | .19 | .71 | .66 | .22 | .63 |

| White or not | .58 | .20 | .55 | .62 | .21 | .59 | .57 | .16 | .54 | .53 | .17 | .51 |

| Group | .14 | .14 | .18 | −.05 | .13 | −.06 | −.11 | .15 | −.14 | |||

| Allele status | 1.0 | .35 | .49** | .14 | 1.2 | .07 | ||||||

| Group × allele status | .54 | .68 | .46 | |||||||||

| R2 | .63 | .66 | .81 | .82 | ||||||||

|

F for change in R2 |

5.4, p = 0.01 | 1.0, p = 0.33 | 8.8, p = 0.01 | 0.64, p = 0.44 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Caudate (N = 18) | ||||||||||||

| Variable | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | P |

| Education | −.03 | .08 | −.10 | −.08 | .08 | −.23 | −.11 | .07 | −.33 | −.14 | .07 | −.41 |

| Age | −.02 | .02 | −.30 | −.02 | .02 | −.25 | −.02 | .01 | −.27 | −.01 | .01 | −.18 |

| Gender | .57 | .33 | .47 | .61 | .30 | .50 | .74 | .28 | .60 | .90 | .26 | .74 |

| White or not | .58 | .33 | .47 | .68 | .26 | .56 | .63 | .24 | .52 | .57 | .22 | .47 |

| Group | .36 | .18 | .39 | .18 | .19 | .20 | .22 | .17 | .25 | |||

| Allele status | .95 | .52 | .39† | .63 | .48 | .26 | ||||||

| Group × allele status | .16 | .08 | .37 | |||||||||

| R2 | .46 | .59 | .69 | .78 | ||||||||

|

F for change in R2 |

2.7, p = 0.07 | 3.9, p = 0.07 | 3.4, p = 0.09 | 4.1, p = 0.07 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Nucleus Accumbens (N = 18) | ||||||||||||

| Variable | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β |

| Education | −.07 | .05 | −.29 | −.09 | .05 | −.37 | −.11 | .05 | −.45 | −.12 | .05 | −.50 |

| Age | −.01 | .01 | −.23 | −.01 | .01 | −.19 | −.01 | .01 | −.21 | −.01 | .01 | −.15 |

| Gender | .60 | .20 | .69 | .62 | .19 | .72 | .69 | .18 | .80 | .77 | .19 | .89 |

| White or not | .52 | .17 | .60 | .57 | .17 | .66 | .54 | .16 | .63 | .51 | .15 | .59 |

| Group | .17 | .11 | .26 | .07 | .12 | .11 | .09 | .12 | .11 | |||

| Allele status | .52 | .34 | .30 | .36 | .34 | .21 | ||||||

| Group × allele status | .08 | .06 | .25 | |||||||||

| R2 | .62 | .68 | .74 | .78 | ||||||||

|

F for change in R2 |

5.4, p = 0.01 | 2.3, p = 0.16 | 2.4, p = 0.15 | 1.9, p = 0.20 | ||||||||

,p ≤ 0.05,

,p ≤ 0.01;

,p = 0.09

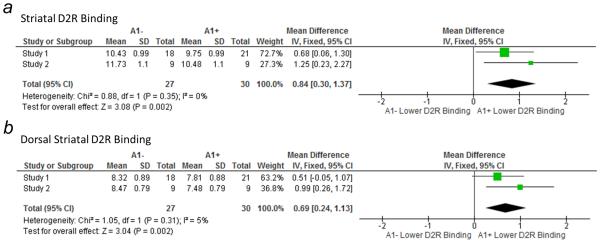

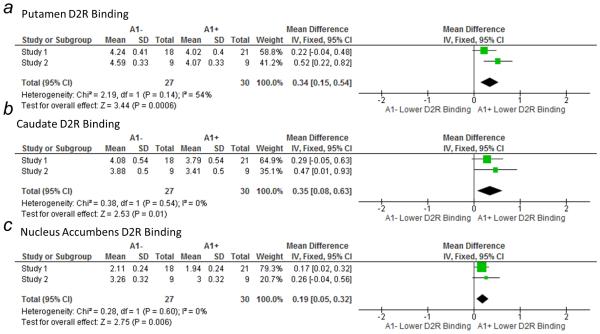

Meta-Analyses

The pooled analyses of Study 1 and Study 2 revealed that D2R specific binding was significantly lower in A1+ relative to A1− across all striatal ROIs (Figs 2, 3).

Figure 2.

Forest plots of the pooled effect sizes for reduced a) striatal and b) dorsal D2R specific binding in A1+ relative to A1− individuals according to study. In both cases, the pooled effect sizes were significant. Size of square is proportional to weight of mean. CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance (statistical method).

Figure 3.

Forest plots of the pooled effect sizes for reduced D2R specific binding, as measured by [11C]NMB, in A1+ relative to A1− individuals in Study 1 and Study 2 in a) putamen, b) caudate, and c) nucleus accumbens. Pooled effect sizes were significant for each ROI. Size of square is proportional to weight of mean. CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance (statistical method).

Discussion

We show in two independent studies that DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA (rs1800497) allele status predicts striatal D2R specific binding in humans, such that A1+ had lower D2R binding relative to A1−. This relationship did not depend on group membership (i.e. non-obese vs obese or controls versus psychosis). Our findings extend previous reports linking DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA allele status to D2/D3R availability in postmortem striatal tissue (Noble et al., 1991; Thompson et al., 1997; Ritchie and Noble, 2003; Gluskin and Mickey, 2016) and in vivo molecular imaging data in humans (Pohjalainen et al., 1998; Jonsson et al., 1999; Hirvonen et al., 2009a; Savitz et al., 2013; Gluskin and Mickey, 2016). Pooled effect sizes, or weighted mean differences, for total and dorsal striatal differences in D2R specific binding between A1+ and A1− were larger (0.84, 0.69) than that calculated for in vivo D2/D3R availability studies (0.57; Gluskin and Mickey, 2016). However, the 95% confidence intervals for total striatum (0.30, 1.37) in our D2R study overlaps with that of D2/D3R availability studies (0.27, 0.87; Gluskin and Mickey, 2016), indicating that our effect size estimates are consistent with those of previous D2/D3R studies. Of note, DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA status accounted for 5-14% of the variance in striatal D2R binding (Tables 2, 4), comparable to 7% of striatal D2/D3R availability in previous in vivo PET studies (Gluskin and Mickey, 2016). Differences in participant characteristics, image analysis methods such as use of arterial input function, outcome measures (Bmax versus BPND), and scanner sensitivity may contribute to variability in strength of the relationship between DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA allele status and D2R binding or D2/D3R availability.

Our results contrast with those of Laruelle et al. (1998), in which D2/D3R availability did not differ between A1+ and A1−. However, that study used SPECT, which has lower resolution than PET. In addition, a large proportion of the sample in Laruelle et al. (1998) were patients with schizophrenia, some of whom may have been taking neuroleptics that increase D2/D3R availability in schizophrenia (Silvestri et al., 2000). Two other previous studies did not find differences in baseline D2/D3R availability between A1+ and A1− (Brody et al., 2006; Wagner et al., 2014) but these included diseased populations including smokers (Brody et al., 2006) and traumatic brain injured individuals (Wagner et al., 2014). Variability in D2/D3R availability measurement due to small sample sizes may have contributed to null findings in these studies. In addition, recent meta-analysis of these D2/D3R studies revealed that the difference in D2/D3R availability between A1+ and A1− is robust in healthy individuals but not in diseased individuals (Gluskin and Mickey, 2016), suggesting that disease may modify this association. Intriguingly, extrastriatal D2/D3R availability, as measured by PET with [11C]FLB457, was elevated in A1+ relative to A1− (Hirvonen et al., 2009b), indicating that there may be differential regulation of D2/D3R across brain regions by DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA allele status. Therefore future studies may investigate the effects of disease on the relationship between TaqIA allele status and D2R specific binding as well as differences in extrastriatal D2R specific binding as measured by PET with [11C]NMB between A1+ and A1−.

There was no significant effect of group on D2R binding in either study. Nor did group interact with TaqIA allele status to predict striatal D2R binding. We have not previously found there to be differences in striatal D2R between an overlapping sample of non-obese and obese individuals (Eisenstein et al., 2013). In the case of study 2, the SCZ group was not large enough to fairly compare striatal D2R binding to HC and SIB. Neither study is truly large enough to investigate the interaction between group and allele status on striatal D2R binding. Therefore, caution should be used in interpreting the null results of these studies. Rather, we emphasize our main finding that when group (and other covariates) was controlled for, striatal D2R binding was lower in A1+ individuals compared to A1− individuals in 2 independent studies.

The mechanism by which the TaqIA variant, which resides in a noncoding region 10 kb downstream from the DRD2 gene (Grandy et al., 1989), influences D2R binding remains unknown. Strong linkage disequilibrium with one or more functional variants, including the DRD2 intronic SNPs rs2283265 and rs1076560 (Zhang et al., 2007) and the ANKK1 missense SNP rs7118900 (Hoenicka et al., 2010), may influence receptor expression (Comings et al., 1991; O'Hara et al., 1993). A likely candidate is the C957T variant (rs6277), which disrupts mRNA stability and synthesis of D2R (Duan et al., 2003) and is in linkage disequilibrium with the TaqIA SNP (Duan et al., 2003). The C957T variant relates to decreased D2/D3R availability as measured in vivo with [11C]raclopride (Hirvonen et al., 2004). However, the C957T variant appears to affect striatal D2/D3R availability by changing receptor affinity while the TaqIA A1 polymorphism contributes to variability in D2/D3R availability by changing Bmax (Hirvonen et al., 2009a). The TaqA1 A1 allele may be instead be in linkage disequilibrium with a functional variant that affects presynaptic DA signaling such as decreased inhibition of striatal DA synthesis (Duan et al., 2003; Laakso et al., 2005), which may displace D2/D3R radioligand binding. However, since endogenous DA does not displace [11C]NMB and we observed lower D2R binding in A1+, it is more likely that the TaqIA allele is in linkage disequilibrium with a functional variant in the DRD2 or ANKK1 gene that directly affects D2R binding.

Limitations of the currently described studies include small sample sizes and heterogeneity of sample composition. Therefore, our power to detect group differences in D2R binding or allele status and interactions between group and allele status was low. Differences in PET scanner characteristics precluded combining data from the two studies for analyses, which would have provided more power. Nonetheless, we still detected relationships between DRD2/ANKK1 allele status and striatal D2R specific binding in the predicted direction and with small to large effect sizes, independent of group membership and PET scanner used. Finally, none of the studies described, including ours, had enough data from healthy A1+ homozygotes to actually test the hypothesis that D2/D3R availability or D2R specific binding is lower in these individuals relative to A1+/A1− and A1−/A1−. To test this hypothesis, given the rare occurrence of homozygosity for A1+, future studies must intentionally select enough healthy participants with A1/A1 to have enough power to detect differences in striatal D2/D3R availability or D2R specific binding between A1/A1, A1/A2, and A2/A2.

In summary, the two independent studies described here showed that DRD2/ANKK1 TaqIA allele status relates to individual differences in striatal D2R specific binding, such that A1+ individuals had greater binding relative to A1−. The use of the novel D2R specific radioligand [11C]NMB with insensitivity to displacement by endogenous DA facilitated measurement of D2R specific binding, in contrast to D2/D3R radioligands such as [11C]raclopride which lacks the same specificity and may be displaced by varying levels of endogenous DA (Moerlein et al., 1997; Karimi et al., 2011). Therefore these studies replicate and extend previous findings from postmortem (Noble et al., 1991; Thompson et al., 1997; Ritchie and Noble, 2003) and PET studies (Pohjalainen et al., 1998; Jonsson et al., 1999; Savitz et al., 2013) performed with D2/D3R radioligands. Our findings also support the hypothesis that the A1 allele (or linked functional variant) may influence risk for substance abuse and psychiatric disorders via D2R, which can be formally tested with mediation analyses.

Acknowledgments

We thank Emily Bihun, Samantha Ranck, Melissa Cornejo, Arthur Schaffer, and Danielle Kelly for their help with recruiting participants. We thank Heather Lugar and Jerrel Rutlin for their help with processing MR scans. The studies presented in this work were conducted using the scanning and special services in the MIR Center for Clinical Imaging Research located at the Washington University Medical Center.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Affective Disorders Young Investigator Award to SAE, the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK085575 to TH, R01 MH066031 to DMB, UL1 TR000448, R01 NS41509 to JSP; R01 NS075321 to JSP; R01 NS058714 to JSP; T32 MH014677 to NSCF; P30 DK056341 to the Washington University Nutrition Obesity Research Center; P30 DK020579 to the Washington University Diabetes Research Center), Barnes Jewish Hospital Foundation (Eliot Stein Family Fund and Parkinson Disease Research Fund) to JSP; the American Parkinson Disease Association (APDA) Advanced Research Center at Washington University to JSP, the Greater St. Louis Chapter of the APDA to JSP, the McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience New Resource Proposal Award to SAE, and the Gregory B. Couch Award to DMB. RB received additional funding from the Klingenstein Third Generation Foundation and NIH (R01 AG045231).

Footnotes

Author roles

SAE, RB, and TH wrote the manuscript. SAE, RB, LLG, NSCF, JMK, KJB, SMM, JSP, DMB, and TH contributed to study design and methods. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

KJB: ACADIA Pharmaceuticals (advisory board, speakers bureau, research funding), Auspex Pharmaceuticals (consultant), Psyadon, Inc. (research funding), Neurocrine Biosciences, Inc. (research funding), and U. S. patent # 8,463,552 and patent application # 13/890,198.

JMK: U. S. patent # 8,463,552 and patent application # 13/890,198.

DMB: Roche (consultant), Takeda Pharmaceuticals U.S.A., Inc. (consultant), Pfizer (consultant), Amgen (consultant).

References

- Antenor-Dorsey JA, Markham J, Moerlein SM, Videen TO, Perlmutter JS. Validation of the reference tissue model for estimation of dopaminergic D2-like receptor binding with [18F](N-methyl)benperidol in humans. Nucl Med Biol. 2008;35:335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arab AH, Elhawxary NA. Association between ANKK1 (rs1800497) and LTA (rs909253) Genetic Variants and Risk of Schizophrenia. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:821827. doi: 10.1155/2015/821827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th Author; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Borg J, Cervenka S, Kuja-Halkola R, Matheson GJ, Jonsson EG, Lichtenstein P, Henningsson S, Ichimiya T, Larsson H, Stenkrona P, Halldin C, Farde L. Contribution of non-genetic factors to dopamine and serotonin receptor availability in the adult human brain. Mol Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody AL, Mandelkern MA, Olmstead RE, Scheibal D, Hahn E, Shiraga S, Zamora-Paja E, Farahi J, Saxena S, London ED, McCracken JT. Gene variants of brain dopamine pathways and smoking-induced dopamine release in the ventral caudate/nucleus accumbens. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:808–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CK, Hu X, Lin SK, Sham PC, Loh el W, Li T, Murray RM, Ball DM. Association analysis of dopamine D2-like receptor genes and methamphetamine abuse. Psychiatr Genet. 2004;14:223–226. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200412000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L, Stokes PR, Wu K, Michalczuk R, Benecke A, Watson BJ, Egerton A, Piccini P, Nutt DJ, Bowden-Jones H, Lingford-Hughes AR. Striatal dopamine D(2)/D(3) receptor binding in pathological gambling is correlated with mood-related impulsivity. Neuroimage. 2012;63:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.06.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comings DE, Rosenthal RJ, Lesieur HR, Rugle LJ, Muhleman D, Chiu C, Dietz G, Gade R. A study of the dopamine D2 receptor gene in pathological gambling. Pharmacogenetics. 1996;6:223–234. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199606000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comings DE, Comings BG, Muhleman D, Dietz G, Shahbahrami B, Tast D, Knell E, Kocsis P, Baumgarten R, Kovacs BW, et al. The dopamine D2 receptor locus as a modifying gene in neuropsychiatric disorders. JAMA. 1991;266:1793–1800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C, Levitan RD, Yilmaz Z, Kaplan AS, Carter JC, Kennedy JL. Binge eating disorder and the dopamine D2 receptor: genotypes and sub-phenotypes. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;38:328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Weijer BA, van de Giessen E, van Amelsvoort TA, Boot E, Braak B, Janssen IM, van de Laar A, Fliers E, Serlie MJ, Booij J. Lower striatal dopamine D2/3 receptor availability in obese compared with non-obese subjects. EJNMMI Res. 2011;1:37. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-1-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan J, Wainwright MS, Comeron JM, Saitou N, Sanders AR, Gelernter J, Gejman PV. Synonymous mutations in the human dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2) affect mRNA stability and synthesis of the receptor. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:205–216. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubertret C, Bardel C, Ramoz N, Martin PM, Deybach JC, Ades J, Gorwood P, Gouya L. A genetic schizophrenia-susceptibility region located between the ANKK1 and DRD2 genes. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34:492–499. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran-Gonzalez J, Ortiz I, Gonzales E, Ruiz N, Ortiz M, Gonzalez A, Sanchez EK, Curet E, Fisher-Hoch S, Rentfro A, Qu H, Nair S. Association study of candidate gene polymorphisms and obesity in a young Mexican-American population from South Texas. Arch Med Res. 2011;42:523–531. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein SA, Gredysa DM, Antenor-Dorsey JA, Green L, Arbelaez AM, Koller JM, Black KJ, Perlmutter JS, Moerlein SM, Hershey T. Insulin, Central Dopamine D2 Receptors, and Monetary Reward Discounting in Obesity. PLoS One. 2015a;10:e0133621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein SA, Koller JM, Piccirillo M, Kim A, Antenor-Dorsey JA, Videen TO, Snyder AZ, Karimi M, Moerlein SM, Black KJ, Perlmutter JS, Hershey T. Characterization of extrastriatal D2 in vivo specific binding of [(1)(8)F](N-methyl)benperidol using PET. Synapse. 2012;66:770–780. doi: 10.1002/syn.21566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein SA, Antenor-Dorsey JA, Gredysa DM, Koller JM, Bihun EC, Ranck SA, Arbelaez AM, Klein S, Perlmutter JS, Moerlein SM, Black KJ, Hershey T. A comparison of D2 receptor specific binding in obese and normal-weight individuals using PET with (N-[(11)C]methyl)benperidol. Synapse. 2013;67:748–756. doi: 10.1002/syn.21680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein SA, Bischoff AN, Gredysa DM, Antenor-Dorsey JA, Koller JM, Al-Lozi A, Pepino MY, Klein S, Perlmutter JS, Moerlein SM, Black KJ, Hershey T. Emotional Eating Phenotype is Associated with Central Dopamine D2 Receptor Binding Independent of Body Mass Index. Sci Rep. 2015b;5:11283. doi: 10.1038/srep11283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr C, Yakushev I, Hohmann N, Buchholz HG, Landvogt C, Deckers H, Eberhardt A, Klager M, Smolka MN, Scheurich A, Dielentheis T, Schmidt LG, Rosch F, Bartenstein P, Grunder G, Schreckenberger M. Association of low striatal dopamine d2 receptor availability with nicotine dependence similar to that seen with other drugs of abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:507–514. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07020352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MBSR, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition With Psychotic Screen (SCID-I/P W/ PSY SCREEN) Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, Albert M, Dieterich M, Haselgrove C, van der Kouwe A, Killiany R, Kennedy D, Klaveness S, Montillo A, Makris N, Rosen B, Dale AM. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33:341–355. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluskin BS, Mickey BJ. Genetic variation and dopamine D2 receptor availability: a systematic review and meta-analysis of human in vivo molecular imaging studies. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e747. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandy DK, Litt M, Allen L, Bunzow JR, Marchionni M, Makam H, Reed L, Magenis RE, Civelli O. The human dopamine D2 receptor gene is located on chromosome 11 at q22-q23 and identifies a TaqI RFLP. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;45:778–785. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haltia LT, Rinne JO, Merisaari H, Maguire RP, Savontaus E, Helin S, Nagren K, Kaasinen V. Effects of intravenous glucose on dopaminergic function in the human brain in vivo. Synapse. 2007;61:748–756. doi: 10.1002/syn.20418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirvonen M, Laakso A, Nagren K, Rinne JO, Pohjalainen T, Hietala J. C957T polymorphism of the dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) gene affects striatal DRD2 availability in vivo. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:1060–1061. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirvonen MM, Laakso A, Nagren K, Rinne JO, Pohjalainen T, Hietala J. C957T polymorphism of dopamine D2 receptor gene affects striatal DRD2 in vivo availability by changing the receptor affinity. Synapse. 2009a;63:907–912. doi: 10.1002/syn.20672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirvonen MM, Lumme V, Hirvonen J, Pesonen U, Nagren K, Vahlberg T, Scheinin H, Hietala J. C957T polymorphism of the human dopamine D2 receptor gene predicts extrastriatal dopamine receptor availability in vivo. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009b;33:630–636. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoenicka J, Quinones-Lombrana A, Espana-Serrano L, Alvira-Botero X, Kremer L, Perez-Gonzalez R, Rodriguez-Jimenez R, Jimenez-Arriero MA, Ponce G, Palomo T. The ANKK1 gene associated with addictions is expressed in astroglial cells and upregulated by apomorphine. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes OD, Kambeitz J, Kim E, Stahl D, Slifstein M, Abi-Dargham A, Kapur S. The nature of dopamine dysfunction in schizophrenia and what this means for treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:776–786. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson EG, Nothen MM, Grunhage F, Farde L, Nakashima Y, Propping P, Sedvall GC. Polymorphisms in the dopamine D2 receptor gene and their relationships to striatal dopamine receptor density of healthy volunteers. Mol Psychiatry. 1999;4:290–296. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambeitz J, Abi-Dargham A, Kapur S, Howes OD. Alterations in cortical and extrastriatal subcortical dopamine function in schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis of imaging studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204:420–429. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.132308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M, Moerlein SM, Videen TO, Luedtke RR, Taylor M, Mach RH, Perlmutter JS. Decreased striatal dopamine receptor binding in primary focal dystonia: a D2 or D3 defect? Mov Disord. 2011;26:100–106. doi: 10.1002/mds.23401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laakso A, Pohjalainen T, Bergman J, Kajander J, Haaparanta M, Solin O, Syvalahti E, Hietala J. The A1 allele of the human D2 dopamine receptor gene is associated with increased activity of striatal L-amino acid decarboxylase in healthy subjects. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15:387–391. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200506000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laruelle M. Imaging dopamine transmission in schizophrenia. A review and meta-analysis. Q J Nucl Med. 1998;42:211–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laruelle M, Gelernter J, Innis RB. D2 receptors binding potential is not affected by Taq1 polymorphism at the D2 receptor gene. Mol Psychiatry. 1998;3:261–265. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawford BR, Young RM, Noble EP, Sargent J, Rowell J, Shadforth S, Zhang X, Ritchie T. The D(2) dopamine receptor A(1) allele and opioid dependence: association with heroin use and response to methadone treatment. Am J Med Genet. 2000;96:592–598. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20001009)96:5<592::aid-ajmg3>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez D, Broft A, Foltin RW, Slifstein M, Hwang DR, Huang Y, Perez A, Frankle WG, Cooper T, Kleber HD, Fischman MW, Laruelle M. Cocaine dependence and d2 receptor availability in the functional subdivisions of the striatum: relationship with cocaine-seeking behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1190–1202. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez D, Gil R, Slifstein M, Hwang DR, Huang Y, Perez A, Kegeles L, Talbot P, Evans S, Krystal J, Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A. Alcohol dependence is associated with blunted dopamine transmission in the ventral striatum. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:779–786. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messas G, Meira-Lima I, Turchi M, Franco O, Guindalini C, Castelo A, Laranjeira R, Vallada H. Association study of dopamine D2 and D3 receptor gene polymorphisms with cocaine dependence. Psychiatr Genet. 2005;15:171–174. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200509000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moerlein SM, Perlmutter JS, Welch MJ. Radiosynthesis of (N-[C-11]methyl)benperidol for PET investigation of D2 receptor binding. Radiochim Acta. 2004;92:333–339. [Google Scholar]

- Moerlein SM, Perlmutter JS, Markham J, Welch MJ. In vivo kinetics of [18F](N-methyl)benperidol: a novel PET tracer for assessment of dopaminergic D2-like receptor binding. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:833–845. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199708000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moerlein SM, LaVenture J, Gaehle GG, Robben J, Perlmutter JS, Mach RH. Automated Production of N-([C-11]Methyl)benperidol ([C-11]NMB) for Clinical Application. Eur J Nucl Med Mol I. 2010;37:S366–S366. [Google Scholar]

- Noble EP, Blum K, Ritchie T, Montgomery A, Sheridan PJ. Allelic association of the D2 dopamine receptor gene with receptor-binding characteristics in alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:648–654. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810310066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble EP, Noble RE, Ritchie T, Syndulko K, Bohlman MC, Noble LA, Zhang Y, Sparkes RS, Grandy DK. D2 dopamine receptor gene and obesity. Int J Eat Disord. 1994;15:205–217. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199404)15:3<205::aid-eat2260150303>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble EP, Blum K, Khalsa ME, Ritchie T, Montgomery A, Wood RC, Fitch RJ, Ozkaragoz T, Sheridan PJ, Anglin MD, et al. Allelic association of the D2 dopamine receptor gene with cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1993;33:271–285. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(93)90113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara BF, Smith SS, Bird G, Persico AM, Suarez BK, Cutting GR, Uhl GR. Dopamine D2 receptor RFLPs, haplotypes and their association with substance use in black and Caucasian research volunteers. Hum Hered. 1993;43:209–218. doi: 10.1159/000154133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons MJ, Mata I, Beperet M, Iribarren-Iriso F, Arroyo B, Sainz R, Arranz MJ, Kerwin R. A dopamine D2 receptor gene-related polymorphism is associated with schizophrenia in a Spanish population isolate. Psychiatr Genet. 2007;17:159–163. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e328017f8a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persico AM, Bird G, Gabbay FH, Uhl GR. D2 dopamine receptor gene TaqI A1 and B1 restriction fragment length polymorphisms: enhanced frequencies in psychostimulant-preferring polysubstance abusers. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40:776–784. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00483-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohjalainen T, Rinne JO, Nagren K, Lehikoinen P, Anttila K, Syvalahti EK, Hietala J. The A1 allele of the human D2 dopamine receptor gene predicts low D2 receptor availability in healthy volunteers. Mol Psychiatry. 1998;3:256–260. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie T, Noble EP. Association of seven polymorphisms of the D2 dopamine receptor gene with brain receptor-binding characteristics. Neurochem Res. 2003;28:73–82. doi: 10.1023/a:1021648128758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz J, Hodgkinson CA, Martin-Soelch C, Shen PH, Szczepanik J, Nugent AC, Herscovitch P, Grace AA, Goldman D, Drevets WC. DRD2/ANKK1 Taq1A polymorphism (rs1800497) has opposing effects on D2/3 receptor binding in healthy controls and patients with major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:2095–2101. doi: 10.1017/S146114571300045X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestri S, Seeman MV, Negrete JC, Houle S, Shammi CM, Remington GJ, Kapur S, Zipursky RB, Wilson AA, Christensen BK, Seeman P. Increased dopamine D2 receptor binding after long-term treatment with antipsychotics in humans: a clinical PET study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;152:174–180. doi: 10.1007/s002130000532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitz MRDM, Pillow P, Hu Y, Amos CI, Hong WK, Wu X. Variant alleles of the D2 dopamine receptor gene and obesity. Nutrition Research. 2000;20:371–380. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Spoor S, Bohon C, Small DM. Relation between obesity and blunted striatal response to food is moderated by TaqIA A1 allele. Science. 2008;322:449–452. doi: 10.1126/science.1161550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas GN, Critchley JA, Tomlinson B, Cockram CS, Chan JC. Relationships between the taqI polymorphism of the dopamine D2 receptor and blood pressure in hyperglycaemic and normoglycaemic Chinese subjects. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2001;55:605–611. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J, Thomas N, Singleton A, Piggott M, Lloyd S, Perry EK, Morris CM, Perry RH, Ferrier IN, Court JA. D2 dopamine receptor gene (DRD2) Taq1 A polymorphism: reduced dopamine D2 receptor binding in the human striatum associated with the A1 allele. Pharmacogenetics. 1997;7:479–484. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199712000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Logan J, Hitzemann R, Ding YS, Pappas N, Shea C, Piscani K. Decreases in dopamine receptors but not in dopamine transporters in alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1594–1598. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb05936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wolf AP, Schlyer D, Shiue CY, Alpert R, Dewey SL, Logan J, Bendriem B, Christman D, et al. Effects of chronic cocaine abuse on postsynaptic dopamine receptors. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:719–724. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.6.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Chang L, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Ding YS, Sedler M, Logan J, Franceschi D, Gatley J, Hitzemann R, Gifford A, Wong C, Pappas N. Low level of brain dopamine D2 receptors in methamphetamine abusers: association with metabolism in the orbitofrontal cortex. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:2015–2021. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AK, Scanlon JM, Becker CR, Ritter AC, Niyonkuru C, Dixon CE, Conley YP, Price JC. The influence of genetic variants on striatal dopamine transporter and D2 receptor binding after TBI. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:1328–1339. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Logan J, Pappas NR, Wong CT, Zhu W, Netusil N, Fowler JS. Brain dopamine and obesity. Lancet. 2001;357:354–357. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03643-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Bertolino A, Fazio L, Blasi G, Rampino A, Romano R, Lee ML, Xiao T, Papp A, Wang D, Sadee W. Polymorphisms in human dopamine D2 receptor gene affect gene expression, splicing, and neuronal activity during working memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20552–20557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707106104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]