Abstract

Previous research suggests that persons living with HIV (PLWH) sometimes internalize HIV-related stigma existing in the community and experience feelings of inferiority and shame due to their HIV status, which can have negative consequences for treatment adherence. PLWH’s interpersonal concerns about how their HIV status may affect the security of their existing relationships may help explain how internalized stigma affects adherence behaviors. In a cross-sectional study conducted between March 2013 and January 2015 in Birmingham, AL, 180 PLWH recruited from an outpatient HIV clinic completed previously validated measures of internalized stigma, attachment styles, and concern about being seen while taking HIV medication. Participants also self-reported their HIV medication adherence. Higher levels of HIV-related internalized stigma, attachment-related anxiety (i.e., fear of abandonment by relationship partners), and concerns about being seen by others while taking HIV medication were all associated with worse medication adherence. The effect of HIV-related internalized stigma on medication adherence was mediated by attachment-related anxiety and by concerns about being seen by others while taking HIV medication. Given that medication adherence is vitally important for PLWH to achieve long-term positive health outcomes, understanding interpersonal factors affecting medication adherence is crucial. Interventions aimed at improving HIV treatment adherence should address interpersonal factors as well as intrapersonal factors.

Keywords: HIV, attachment, attachment-related anxiety, stigma, adherence, interpersonal

INTRODUCTION

Current estimates by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) place the number of people living with HIV (PLWH) in the United States (U.S.) at 1.24 million (1). Within the U.S., the Deep South region has been characterized as the epicenter of the HIV epidemic, with HIV incidence and fatality rates reported to be the highest in the nation (2). Furthermore, conservative political and religious leanings combined with lower levels of education may facilitate a more hostile social environment for PLWH in the Deep South (3-6).

Although significant health disparities in treatment outcomes exist throughout the U.S., testing positive for HIV is no longer a death sentence. Improvements in antiretroviral therapy (ART) have resulted in reduced mortality rates, increases in quality of life, as well as reduced likelihood of transmission to others. However, these favorable outcomes can only be achieved with sustained and optimal medication adherence over time (7, 8). Despite the importance of adherence to ART, achieving high and consistent levels of adherence for many PLWH remains challenging (9-11). It may be useful to apply insights from social psychology to examine the role of specific interpersonal processes in medication adherence for PLWH, especially in the Deep South, where HIV-related stigma may be a very important social factor (2-6, 12).

HIV-Related Stigma

Conceptualizations of HIV-related stigma have evolved over the years to an understanding that stigma is a complex social process (13) in which individuals with a socially devalued characteristic (in this case, HIV infection) may experience prejudice, stereotyping, labeling, or devaluation (14-16). As a result of HIV-related stigma, PLWH can experience discrimination, rejection, and social exclusion in their daily lives, which is referred to as experienced or enacted stigma. In addition, some PLWH may anticipate negative attitudes and acts of discrimination because of their HIV status, which is referred to as anticipated stigma (17).

Furthermore, stigma can be internalized when PLWH endorse and adopt assumptions about their “spoiled” identity (18) due to having HIV, and experience feelings of shame and inferiority. It is possible that people with a stigmatized condition have higher internalized stigma in regions and communities where a particular stigma is stronger (e.g., the U.S. Deep South) (19, 20). The diminished view of self associated with internalized HIV stigma can lead to maladaptive health behaviors such as avoiding taking HIV medications. Several studies examining the association between internalized HIV-related stigma and medication adherence provided support for this association (21-24), although some studies failed to find a significant association between internalized HIV-related stigma and medication adherence (e.g., 25).

Identifying mediating mechanisms in the association between internalized HIV stigma and sub-optimal medication adherence is important for both theoretical and practical reasons. Previous research has suggested that internalized stigma is linked to a variety of intrapersonal problems such as depression and poor mental health (26), which may explain the negative effects of internalized HIV stigma on medication adherence. Research has supported the hypothesis that the association between internalized HIV stigma and sub-optimal medication adherence is mediated by depression and mental health problems (22, 24, 27). However, research examining the mediating role of interpersonal factors is more scarce. There is evidence that internalized stigma is associated with some interpersonal factors such as loneliness and lower social support (19, 28, 29), which may mediate the association between internalized HIV stigma and poor medication adherence (24). However, to our knowledge, no studies have examined the association of other important interpersonal constructs, such as attachment styles and interpersonal worry, with medication adherence; and more importantly, the mediating role of these interpersonal factors in the association between internalized HIV stigma and poor medication adherence.

Attachment-Related Anxiety

Attachment style, a construct related to patterns of relating in close relationships, is one of the most frequently studied interpersonal constructs in social psychological research (30). According to attachment theory (31, 32), people develop attachment styles, which guide their intimate relationships throughout their lives. A secure attachment style is characterized by being comfortable in giving and receiving support in relationships and perceiving one’s self as competent in dealing with stressors. There are two insecure attachment dimensions: attachment-related anxiety and attachment-related avoidance. Attachment-related anxiety is characterized by a negative self-image, chronic worries about relationship partners’ availability, fears of abandonment, and a need for frequent validation and support from partners. Attachment-related avoidance is characterized by feelings of discomfort with emotional intimacy and a reluctance towards giving and receiving support during times of stress. Applying these constructs to health research, investigators have found that attachment styles predict treatment adherence in several chronic diseases such as diabetes (33) and lupus (34).

Although a person’s attachment style is moderately stable once formed, considerable evidence suggests that it can be altered over time via attachment-related experiences, such as negative evaluation by close others in the form of criticism, disapproval, rejection, and abandonment (35-38) (for a comprehensive review see Mikulincer and Shaver's book on adult attachment 30). However, not everyone facing criticism and rejection shifts toward insecure attachment styles (39). Davila and Cobb (40) argue that, “… the effect of events on change in attachment models might be cognitively mediated through subjective perceptions” (pp. 143–144). Findings of Davila and Sargent (41) support this view: In their diary study, negative interpersonal experiences on a certain day predicted decreases in self-reported attachment security on that day (a within-person association), especially when participants construed these events as damaging their status in their relationships. Thus, living with HIV and facing stigma and discrimination by close others may shift PLWH toward insecure attachment, especially if their subjective perceptions of themselves and their perceived position in their relationships become more negative. It is plausible that PLWH who have high levels of internalized stigma (i.e., subjective feelings of being inferior due to living with HIV) show higher levels of insecure attachment (particularly attachment-related anxiety).

We hypothesized that attachment-related anxiety may be associated with poorer medication adherence for PLWH, because taking medication around loved ones may lead to exacerbated worries about rejection and abandonment. To avoid these interpersonal concerns, PLWH may seek opportunities to take their pills in seclusion, but often at the cost of failing to meet the demands for being consistent with their medication (42, 43). Similarly, attachment-related avoidance should be associated with worse treatment adherence since avoidance of distressing situations is a defining characteristic of attachment-related avoidance. Thus, theoretically, it is plausible that attachment-related anxiety and attachment-related avoidance are among the mechanisms that mediate the association between internalized stigma and sub-optimal medication adherence.

Concerns About Being Seen While Taking HIV Medication

Theoretically, concern about being seen while taking HIV-medication is closely related to attachment-related anxiety and internalized stigma. According to previous research, this concern is related to efforts made by PLWH to avoid negative evaluation by others and has been linked to poor medication adherence (43). However, no studies have linked this concept to a larger interpersonal paradigm like attachment styles. Mapping the role of concern about being seen while taking HIV medication to larger theoretical constructs such as internalized stigma and attachment-related anxiety may lead to a more accurate understanding of the interpersonal mechanisms leading to poor medication adherence for PLWH.

Current Research and Hypotheses

In a cross-sectional study, we investigated the association between attachment styles and HIV medication adherence, as well as the mediating role of attachment styles in the association between internalized stigma and medication adherence. We also examined the role of concern about being seen while taking HIV medication as another mediating mechanism explaining the association between internalized stigma and HIV medication adherence. Combining these hypotheses, we expected a chain effect of internalized stigma in a sequential way (i.e., internalized stigma is associated with attachment-related anxiety, which in turn leads to concern about being seen while taking HIV medication, which in turn leads to poor medication adherence). We recognized that alternative directionalities for these relationships were also theoretically plausible (e.g., attachment anxiety could lead to internalized HIV stigma) and tested alternative models along these lines as well.

METHODS

Participants

The study was conducted between March 2013 and January 2015 in Birmingham, AL. Patients from an outpatient HIV clinic at the University of Alabama at Birmingham were invited to participate in separate research visits, providing written informed consent to participate in this IRB approved research protocol. Exclusion criteria included not being on ART medication and/or being a current substance user. Patients who agreed to participate (N = 198) completed study measures as part of a larger study on daily experiences living with HIV (44). Participants were compensated $30 for completing the questionnaires. In the current analyses, 180 participants without missing data on the primary study variables were included.(1) The date when each participant initiated ART medication was extracted from the clinic data. Demographic information was obtained through self-report and cross-checked with clinic data.

Measures

Medication Adherence

To assess adherence, we used a single-item self-report scale. Previous research suggests that this single item scale is a valid measure of adherence (45, 46). Participants reported their ability to take all of their anti-HIV medications that were prescribed using a 6-point rating scale ranging from 1 (very poor) to 6 (excellent). The scores on this measure were not normally distributed, with 128 participants reporting excellent adherence and 52 reporting less than excellent adherence. Therefore, this measure was dichotomized: Excellent adherence (1) versus less than excellent adherence (0). Although self report tends to overestimate adherence, prior research has consistently demonstrated the negative predictive value of any self-reported non-adherence (i.e., less than excellent adherence (47)).

Internalized stigma

Participants responded to a multi-dimensional HIV stigma scale developed by Berger et al. (19) and revised by Bunn et al. (48). For the purposes of testing our hypothesis, we focused on the 7-item internalized stigma subscale. This Likert-type scale (using ratings from 1-strongly agree to 4-strongly disagree) included items such as “Having HIV in my body is disgusting to me” and “I feel guilty because I have HIV.” This measure showed high internal consistency in the present study (Cronbach’s α = .85). The mean of the seven items was reverse coded and utilized as the variable of interest. Higher scores reflect higher internalized stigma.

Attachment Styles

We used a shorter 18-item version of the most widely used attachment style measure: Experiences in Close relationships (ECR; (32)). ECR assesses two dimensions of insecure attachment: anxiety and avoidance. A sample item of the anxiety scale is “I worry about being abandoned,” and a sample item of the avoidance scale is “I am nervous when partners get too close to me.” Participants rated each item on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). In the present data, both anxiety and avoidance scales showed high internal consistency; Cronbach’s α = .89 for both dimensions. Attachment-related anxiety and attachment-related avoidance showed a substantial correlation (r = .61, p < .001).

Concern about being seen taking HIV medication

To our knowledge, there is not a multi-item scale assessing this construct. However, we found two items from two different measures that tap into this construct: (a) The item “I don’t want people to see me take my HIV medicines” from the Patient Medication Adherence Questionnaire Version 1.0 (PMAQ-V1.0 (49)), and (b) The item “Did not want others to notice you taking medication” from the Adult AIDS Clinical Trial Group Adherence to Combination Therapy (AACTG) Questionnaire (50). Participants’ responses to these items were standardized (i.e., transformed into z scores by subtracting the sample mean from each score and then dividing by the sample standard deviation, so that the two items would be comparable) and averaged. Higher scores indicate higher concern about being seen while taking HIV medication.

Data Analyses

First, descriptive statistics and bivariate Pearson correlations among the study variables were calculated. In all of the analyses, the following covariates were controlled: age, racial identity, gender identity, socioeconomic status, and duration of ART use. A logistic regression analysis was used to test whether attachment-related anxiety is associated with medication adherence (a dichotomous outcome) by entering attachment-related anxiety and the covariates simultaneously as independent variables. Similar logistic regression analyses were conducted using attachment-related avoidance or concern about being seen while taking HIV medication, or internalized stigma (in addition to the covariates) as the independent variable instead of attachment-related anxiety. Multiple regression analyses were used to assess the associations between internalized HIV stigma and attachment-related anxiety or concern about being seen while taking HIV medication (again controlling for the covariates using simultaneous entry for all independent variables).

To test for the mediating effects of our interpersonal factors (attachment-related anxiety, concerns about being seen while taking HIV medication) in the stigma-adherence relationship, we calculated bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for indirect effects using bootstrapping with the Process procedure developed by Hayes (51). We also calculated indirect effects to test a serial mediation hypothesis that stigma leads to attachment-related anxiety, which in turn leads to concerns about being seen while taking HIV medication, which in turn leads to lower medication adherence (see Figures 1, 2, and 3). Like all other analyses, all mediation analyses controlled for the covariates mentioned above. An alpha level of 0.05 was used for all analyses.

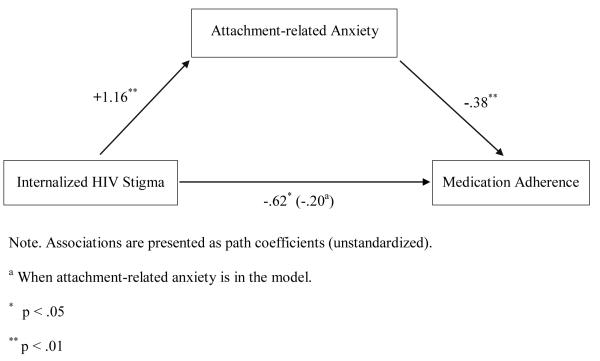

Figure 1.

Attachment-related anxiety mediates the effect of internalized HIV stigma on medication adherence.

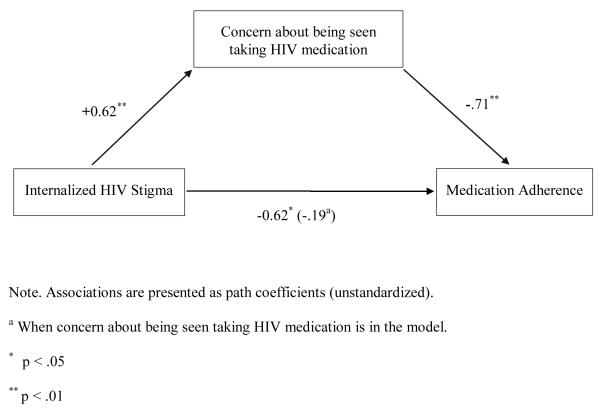

Figure 2.

Concern about being seen taking HIV medication mediates the effect of internalized HIV stigma on medication adherence.

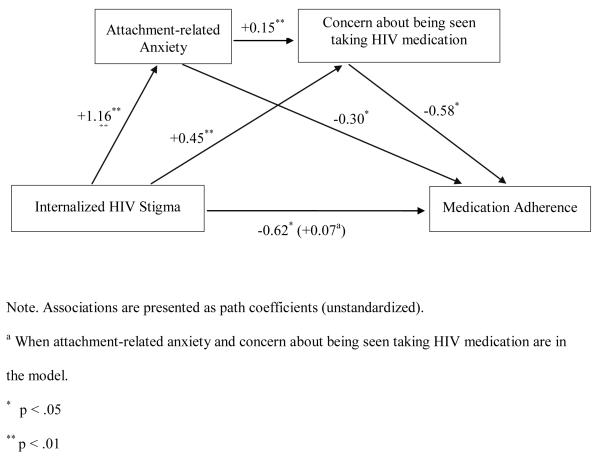

Figure 3.

Attachment-related anxiety and concern about being seen taking HIV medication mediate the effect of internalized HIV stigma on medication adherence.

RESULTS

Of the 180 participants 62% were Black and 64% were male, with an average age of 45.37 years (SD = 10.96). Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among the study variables are presented in Table 1 and Table 2. As seen in Table 2, internalized HIV stigma, attachment-related avoidance, attachment-related anxiety, and concern about being seen while taking HIV medication were moderately correlated. In separate analyses, both attachment-related anxiety (see Table 3) and attachment-related avoidance were significantly associated with poorer medication adherence (controlling for the covariates; Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) = 0.66, p = .001, 95% CI [0.51, 0.84] and AOR = 0.70, p = .01, 95% CI [0.53, 0.91], respectively). However, when both attachment dimensions were entered simultaneously, only attachment-related anxiety was significantly associated with poorer medication adherence (controlling for the covariates; AOR = 0.70, p = .02, 95% CI [0.52, 0.95] and AOR = 0.87, p = .39, 95% CI [0.63, 1.20], respectively for anxiety and avoidance).(2) An odds ratio of 0.70 corresponds to an odds ratio of 1.43 when attachment-related anxiety scores are reverse coded (i.e., higher scores reflect lower attachment-related anxiety), which suggests that the odds of optimal adherence increases 43% for each scale point decrease in attachment-related anxiety.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics on the study variables

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Race | |

| Black | 112 (62.2) |

| White | 68 (37.8) |

|

| |

| Sex | |

| Male | 115 (63.9) |

| Female | 65 (36.1) |

|

| |

| SES | |

| Lower | 25 (13.9) |

| Lower Middle | 44 (24.4) |

| Middle | 81 (45.0) |

| Upper Middle | 26 (14.4) |

| Upper | 4 (2.2) |

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 45.37 (10.96) | 24 – 71 |

| Time Since Starting ART Medication (Months) | 98.16 (63.93) | 12 – 242 |

| Internalized Stigma | 1.96 (0.67) | 1.00 – 4.00 |

| Attachment-related Avoidance | 3.09 (1.43) | 1.00 – 7.00 |

| Attachment-related Anxiety | 3.55 (1.55) | 1.00 – 7.00 |

| Concern about being seen taking HIV medication | −0.02 (0.82) | −0.82 – 2.42 |

Note. ART = Antiretroviral therapy.

Table 2.

Pearson Correlations among Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | |||||

| 2. Time Since Starting ART (Months) | 0.47** | 1.00 | |||

| 3. Internalized Stigma | −0.14 | −0.07 | 1.00 | ||

| 4. Attachment-related Avoidance | −0.04 | 0.00 | 0.50** | 1.00 | |

| 5. Attachment-related Anxiety | −0.18* | −0.13 | 0.55** | 0.61** | 1.00 |

| 6. Concern about being seen taking HIV medication |

−0.25** | −0.08 | 0.52** | 0.36** | 0.48** |

Note. ART = Antiretroviral therapy.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Analyses where Attachment-related Anxiety is used to Predict Medication Adherence When Internalized HIV Stigma is in the Model and when it is not

| Predictor | SE | AOR1 | p | SE | AOR1 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Attachment-related Anxiety | .13 | .66 | .001 | .14 | .68 | .008 |

| Age | .02 | 1.00 | .961 | .02 | 1.00 | .998 |

| Race | .45 | .21 | .000 | .45 | .20 | .000 |

| Sex | .42 | .69 | .378 | .42 | .70 | .390 |

| SES | .20 | 1.08 | .698 | .20 | 1.06 | .756 |

| Time on ART | .00 | 1.00 | .817 | .00 | 1.00 | .848 |

| Internalized HIV Stigma | — | — | — | .32 | .81 | .514 |

AOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio

Note. ART = Antiretroviral therapy.

Internalized stigma was significantly associated with higher attachment-related anxiety (β = 0.46, t = 7.52, p < .001) as well as higher attachment-related avoidance (β = 0.46, t = 7.34, p < .001). Internalized stigma was also significantly associated with poorer medication adherence (AOR = 0.54, p = .02, 95% CI [0.31, 0.92]). When internalized stigma was entered simultaneously with attachment-related anxiety (see Table 3), the effect of attachment-related anxiety remained significant (AOR = 0.68, p = .008, 95% CI [0.52, 0.91]), while internalized stigma became non-significant (AOR = 0.81, p = .51, 95% CI [0.44, 1.51]). The indirect effect of internalized stigma through attachment-related anxiety was significant (B = −0.44, SE = 0.19, 95% CI [−0.84, −0.09]), suggesting that attachment-related anxiety mediates the effect of internalized stigma on adherence (see Figure 1). (3) We also tested the alternative hypothesis that internalized HIV-related stigma mediates the association between attachment-related anxiety and sub-optimal adherence, which yielded a non-significant indirect effect (B = −0.46, SE = 0.08, 95% CI [−0.20, 0.11]).

Concern about being seen while taking HIV medication was also significantly associated with poorer medication adherence (controlling for the covariates, AOR = 0.45, p = .001, 95% CI [0.29, 0.71]). Furthermore, internalized stigma was significantly associated with concern about being seen taking HIV medication, (β = 0.49, t = 8.00, p < .001)(4). When internalized stigma was entered simultaneously with concern about being seen while taking HIV medication, the effect of concern about being seen while taking HIV medication remained significant (AOR = 0.49, p = .007, 95% CI [0.29, 0.82]), while internalized stigma became non-significant (AOR = 0.83, p = .56, 95% CI [0.44, 1.56]).

Next, we tested for a mediating effect of concern about being seen while taking HIV medication in the relationship between internalized stigma and medication adherence. Again, we calculated bias-corrected 95% CI using bootstrapping with the Process procedure. The indirect effect of internalized stigma through concern about being seen while taking HIV medication was significant, (B = −0.44, SE = 0.21, CI [−0.87, −0.07]), suggesting that this interpersonal factor also mediated the effect of internalized stigma on adherence (see Figure 2).

Serial mediation assumes “a causal chain linking the mediators, with a specified direction of causal flow” (51) (p. 14). To better understand the effects of our interpersonal factors, we tested the serial mediation model depicted in Figure 3: Internalized stigma leads to attachment-related anxiety, which leads to concern about being seen while taking HIV medication, which in turn leads to poor medication adherence. The bias-corrected 95% CI suggested a significant indirect effect for serial mediation; the indirect effect of internalized stigma on medication adherence through attachment-related anxiety and then through concern about being seen while taking HIV medication was significant, (B = −0.10, SE = .07, CI [−0.26, −0.004]).(3)

DISCUSSION

The results of this study support the hypothesis that attachment patterns and concerns about being seen while taking HIV medication are associated with sub-optimal HIV medication adherence and mediate the relationship between internalized HIV-related stigma and sub-optimal medication adherence. Results of our serial mediation analysis further elucidated a potential multi-variable chain mechanism, suggesting that stigma is associated with attachment-related anxiety, which in turn is associated with concerns about being seen while taking HIV medication, which in turn is associated with sub-optimal medication adherence. Internalizing social stigma likely creates negative appraisals of self, leading to anxiety and expectations of negative judgment from others, both of which are likely to result in sub-optimal medication adherence. Future research should further examine the pathways for the effects of other types of HIV-related stigma (e.g., anticipated or experienced stigma) on medication adherence and on other outcomes (17). Does anticipated or experienced stigma affect medication adherence differently? What are the complex mechanisms in the joint effects of different types of HIV-related stigma on outcomes? What is the nature of these effects in places where HIV-related stigma is strong in the community?

As mentioned above, our results suggest that internalized stigma leads to attachment-related anxiety. However, the alternative hypothesis that attachment-related anxiety would lead to internalized stigma is also plausible, given that there is evidence for attachment patterns being stable as well as malleable due to experience (30). Our analyses did not support this alternative hypothesis: the mediating effect of internalized stigma in the attachment-related anxiety and sub-optimal adherence was not significant. However, future research is needed to elucidate the direction of these relationships using longitudinal study designs. Attachment-related avoidance was also associated with sub-optimal medication adherence. However, when entered together with attachment-related anxiety, the effect of attachment-related avoidance on medication adherence was no longer significant. In our sample of PLWH, the correlation between attachment-related anxiety and attachment-related avoidance was r = .61, which is substantially higher than the correlation found in non-clinical samples (which is around r = .15 according to a meta-analysis (52)). The high correlation we observed may be due to higher interpersonal concerns within this sample of people living with HIV, and the problem of multi-collinearity might have attenuated the observed effect of attachment-related avoidance in our analyses. It is also possible that the effect of attachment-related avoidance is mediated by attachment-related anxiety, leading to a non-significant effect of attachment-related avoidance when entered together with attachment-related anxiety.

Findings of the current investigation support the hypothesis that the interpersonal factors attachment-related anxiety and concerns about being seen while taking HIV medication may mediate the relationship between internalized HIV stigma and sub-optimal medication. Targeted interventions aimed at addressing these interpersonal factors may help to improve medication adherence and HIV-treatment outcomes overall. PLWH can learn to develop effective coping strategies designed to increase their self-esteem and reduce interpersonal relationship anxiety. Interventions utilizing Cognitive Behavioral Therapy techniques have shown some success in reducing perceived stigma in other domains by fostering empowering discussions on the illegitimacy of stigmatizing attitudes and encouraging group members to think about how they respond to such stigma (53, 54). PLWH’s feelings of alienation due to their HIV status may be helped by having opportunity to meet other PLWH and seek social support from others who best can empathize with their situation. In addition to these strategies, interventions can also target relationship partners of PLWH in an effort to reduce the negative interpersonal effects of HIV-related stigma. Interventions targeting couples have yielded promising results in randomized controlled trials (55). If partners of PLWH could improve their understanding of the relationship insecurities of their partners, and learn to make their partners feel more confident about their relationship, this may help PLWH to engage in less deleterious coping behaviors, improving adherence (54). Utilizing all of these methods with loved ones, others living with HIV, and sensitive caregivers, PLWH may show better resilience against stigma and interpersonal concerns that get in the way of optimal medication adherence.

This study had some limitations. Because our analyses utilized self-report measures, our findings are limited to the validity of those self-reports. Our study was cross-sectional and relied on questionnaire measures, which precludes causal inferences (even though our mediation models are supported by theory and previous research). Future research is needed to elucidate the direction of these relationships using longitudinal study designs. Future research can also utilize non-questionnaire measures such as the experience sampling method (also known as ecological momentary assessment), which is beginning to be utilized in HIV research (44). All of the participants were recruited from a single HIV clinic located within a research university, which provides comprehensive social work and clinical services. It is possible that the high quality of comprehensive care that the clinic provides limits generalizability of our findings. Furthermore, our sample did not include current substance users, which also limits the generalizability of our findings.

Although research on HIV-related stigma and adherence has suggested that internalized stigma is important in understanding adherence to HIV medications, there is a paucity of research examining the mediating mechanisms involved. The few existing studies on mediating mechanisms have mainly focused on intrapersonal factors such as depression (22, 24). Given that stigma is an interpersonal construct by definition, it is surprising that previous research has not examined attachment styles and related interpersonal constructs as predictors of medication adherence or as mediating mechanisms in the stigma-adherence association.

The present results suggest that those PLWH with higher attachment-related anxiety and avoidance are less likely to adhere to HIV medications, with attachment-related anxiety mediating the effect of internalized stigma on sub-optimal medication adherence. Given the complex multi-variable relationship between internalized stigma, negative interpersonal factors, and medication adherence, there is a need for further research aimed at investigating these and other interpersonal factors in more detail. Future studies examining the role of attachment styles in the larger nomological network of associated interpersonal constructs may provide a clearer model for understanding health outcomes for PLWH. It is suggested that interventions aim to target multiple interpersonal factors, including stigma, coping styles, and attachment styles, as these factors may prove critical in improving HIV treatment outcomes overall.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Center for AIDS Research CFAR, an NIH funded program (P30 AI027767) that was made possible by the following institutes: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHLBI, NIDA, NIA, NIDDK, NIGMS, and OAR. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). We would like to thank Maria Lechtreck, Wesley Browning, Christy Thai, and all the research assistants for their help in data collection. This article is based in part on an undergraduate honors thesis conducted by C. Blake Helms' under the supervision of Dr. Bulent Turan at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Footnotes

Participants without missing data did not differ from participants with missing data on any of the study variables (all p values > .11), except that participants without missing data were older (t = 2.56, p = .01).

The interaction of avoidance and anxiety did not show a significant effect on medication adherence.

The indirect effect was also significant when controlling for avoidance.

Concern about being seen taking HIV medication was not normally distributed (Kolmogorov-Smirnov z = 2.20, p < .05). However, a regression analysis using bootstrapping (with 1000 bootstrapping samples), which does not require a normal distribution, yielded very similar results.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV surveillance report, 2012. 2012.

- 2.Reif SS, Whetten K, Wilson ER, McAllaster C, Pence BW, Legrand S, et al. HIV/AIDS in the Southern USA: A disproportionate epidemic. AIDS Care. 2014;26(3):351–9. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.824535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baunach DM, Burgess EO. HIV/AIDS Prejudice in the American Deep South. Sociological Spectrum. 2013;33(2):175–95. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heckman TG, Somlai A, Peters J, Walker J, Otto-Salaj L, Galdabini C, et al. Barriers to care among persons living with HIV/AIDS in urban and rural areas. AIDS Care. 1998;10(3):365–75. doi: 10.1080/713612410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reif S, Golin C, Smith S. Barriers to accessing HIV/AIDS care in North Carolina: rural and urban differences. AIDS Care. 2005;17(5):558–65. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331319750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stringer KL, Turan B, McCormick L, Durojaiye M, Nyblade L, Kempf M-C, et al. HIV-Related Stigma Among Healthcare Providers in the Deep South. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(1):115–25. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1256-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrigan PR, Hogg RS, Dong WW, Yip B, Wynhoven B, Woodward J, et al. Predictors of HIV drug-resistance mutations in a large antiretroviral-naive cohort initiating triple antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(3):339–47. doi: 10.1086/427192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mannheimer S, Matts J, Telzak E, Chesney M, Child C, Wu A, et al. Quality of life in HIV-infected individuals receiving antiretroviral therapy is related to adherence. AIDS Care. 2005;17(1):10–22. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331305098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beer L, Fagan JL, Garland P, Valverde EE, Bolden B, Brady KA, et al. Medication-related barriers to entering HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(4):214–21. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beer L, Oster AM, Mattson CL, Skarbinski J. Disparities in HIV transmission risk among HIV-infected black and white men who have sex with men, United States, 2009. AIDS. 2014;28(1):105–14. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 US dependent areas—2010. HIV surveillance supplemental report. 2012;17(3) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lichtenstein B. Stigma as a barrier to treatment of sexually transmitted infection in the American deep south: issues of race, gender and poverty. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(12):2435–45. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual review of Sociology. 2001:363–85. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Earnshaw VA, Chaudoir SR. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1160–77. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9593-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VA, Remien RH, Ortiz D, Szekeres G, et al. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS. 2008;22:S67–S79. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000327438.13291.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Link BG, Phelan JC. Stigma and its public health implications. The Lancet. 2006;367(9509):528–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Amico KR, Copenhaver MM. HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: a test of the HIV stigma framework. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(5):1785–95. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0437-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goffman E. Stigma; notes on the management of spoiled identity. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(6):518–29. doi: 10.1002/nur.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cox WT, Abramson LY, Devine PG, Hollon SD. Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Depression The Integrated Perspective. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2012;7(5):427–49. doi: 10.1177/1745691612455204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DiIorio C, McCarty F, Depadilla L, Resnicow K, Holstad MM, Yeager K, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral medication regimens: a test of a psychosocial model. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(1):10–22. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9318-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rao D, Feldman BJ, Fredericksen RJ, Crane PK, Simoni JM, Kitahata MM, et al. A structural equation model of HIV-related stigma, depressive symptoms, and medication adherence. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(3):711–6. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9915-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sayles JN, Ryan GW, Silver JS, Sarkisian CA, Cunningham WE. Experiences of social stigma and implications for healthcare among a diverse population of HIV positive adults. J Urban Health. 2007;84:814–28. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9220-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turan B, Smith W, Cohen MH, Wilson TE, Adimora AA, Merenstein D, Adedimeji A, Wentz EL, Foster AG, Metsch L, Tien PC, Weiser SD, Turan JM. Mechanisms for the negative effects of internalized HIV-related stigma on ART adherence in women: The roles of social isolation and depression. JAIDS. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000948. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalichman SC, Pope H, White D, Cherry C, Amaral CM, Swetzes C, et al. Association Between Health Literacy and HIV Treatment Adherence: Further Evidence from Objectively Measured Medication Adherence. Journal of the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care (JIAPAC) 2008;7(6):317–23. doi: 10.1177/1545109708328130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phillips KD, Moneyham L, Tavakoli A. Development of an instrument to measure internalized stigma in those with HIV/AIDS. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2011;32(6):359–66. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2011.575533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sayles JN, Wong MD, Kinsler JJ, Martins D, Cunningham WE. The Association of Stigma with Self-Reported Access to Medical Care and Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence in Persons Living with HIV/AIDS. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(10):1101–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1068-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vyavaharkar M, Moneyham L, Corwin S, Saunders R, Annang L, Tavakoli A. Relationships between stigma, social support, and depression in HIV-infected African American women living in the rural Southeastern United States. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2010;21(2):144–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takada S, Weiser SD, Kumbakumba E, Muzoora C, Martin JN, Hunt PW, et al. The dynamic relationship between social support and HIV-related stigma in rural Uganda. Ann Behav Med. 2014;48(1):26–37. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9576-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. Guilford; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowlby J. A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human behavior. Basic Books; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. Guilford Press; New York: 1998. pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turan B, Osar Z, Turan JM, Ilkova H, Damci T. Dismissing attachment and outcome in diabetes: The mediating role of coping. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2003;22(6):607–26. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bennett JK, Fuertes JN, Keitel M, Phillips R. The role of patient attachment and working alliance on patient adherence, satisfaction, and health-related quality of life in lupus treatment. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(1):53–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davila J, Karney B, Bradbury T. Attachment change processes in the early years of marriage. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;76(5):783–802. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.5.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirkpatrick LA, Hazan C. Attachment styles and close relationships: A four-year prospective study. Personal relationships. 1994;1(2):123–42. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feeney JA, Noller P. Attachment style and romantic love: Relationship dissolution. Aust J Psychol. 1992;44(2):69–74. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruvolo AP, Fabin LA, Ruvolo CM. Relationship experiences and change in attachment characteristics of young adults: The role of relationship breakups and conflict avoidance. Personal Relationships. 2001;8(3):265–81. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davila J, Cobb RJ. Predicting change in self-reported and interviewer-assessed adult attachment: Tests of the individual difference and life stress models of attachment change. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29(7):859–70. doi: 10.1177/0146167203029007005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davila J, Cobb RJ. Predictors of Change in Attachment Security during Adulthood. In: Simpson WSRJA, editor. Adult attachment: Theory, research, and clinical implications. Guilford Publications; New York, NY, US: 2004. pp. 133–56. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davila J, Sargent E. The meaning of life (events) predicts changes in attachment security. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29(11):1383–95. doi: 10.1177/0146167203256374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boehme AK, Davies SL, Moneyham L, Shrestha S, Schumacher J, Kempf M-C. A qualitative study on factors impacting HIV care adherence among postpartum HIV-infected women in the rural southeastern USA. AIDS Care. 2014;26(5):574–81. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.844759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rintamaki LS, Davis TC, Skripkauskas S, Bennett CL, Wolf MS. Social stigma concerns and HIV medication adherence. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20(5):359–68. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turan B, Fazeli P, Raper JL, Mugavero MJ, Johnson MO. Social support and moment-to-moment changes in treatment self-efficacy in men living with HIV: Psychosocial moderators and clinical outcomes. Health Psychol. doi: 10.1037/hea0000356. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feldman B, Fredericksen R, Crane P, Safren S, Mugavero M, Willig JH, et al. Evaluation of the single-item self-rating adherence scale for use in routine clinical care of people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(1):307–18. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0326-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu M, Safren SA, Skolnik PR, Rogers WH, Coady W, Hardy H, et al. Optimal recall period and response task for self-reported HIV medication adherence. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(1):86–94. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thompson MA, Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Cargill VA, Chang LW, Gross R, et al. Guidelines for improving entry into and retention in care and antiretroviral adherence for persons with HIV: evidence-based recommendations from an International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care panel. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(11):817–33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-11-201206050-00419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bunn JY, Solomon SE, Miller C, Forehand R. Measurement of stigma in people with HIV: a reexamination of the HIV Stigma Scale. AIDS Educ Prev. 2007;19(3):198–208. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.3.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DeMasi RA, Graham NM, Tolson JM, Pham SV, Capuano GA, Fisher RL, et al. Correlation between self-reported adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and virologic outcome. Adv Ther. 2001;18(4):163–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02850110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL, Neidig J, Zwickl B, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. Patient Care Committee & Adherence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG) AIDS Care. 2000;12(3):255–66. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cameron JJ, Finnegan H, Morry MM. Orthogonal dreams in an oblique world: A meta-analysis of the association between attachment anxiety and avoidance. J Res Pers. 2012;46(5):472–6. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Knight MT, Wykes T, Hayward P. Group treatment of perceived stigma and self-esteem in schizophrenia: a waiting list trial of efficacy. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2006;34(03):305–18. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heijnders M, Van Der Meij S. The fight against stigma: an overview of stigma-reduction strategies and interventions. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11(3):353–63. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crepaz N, Tungol-Ashmon MV, Vosburgh HW, Baack BN, Mullins MM. Are couple-based interventions more effective than interventions delivered to individuals in promoting HIV protective behaviors? A meta-analysis. AIDS Care. 2015:1–6. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1112353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]