Abstract

Gastric carcinoids are slow growing neuroendocrine tumors arising from enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells in the corpus of stomach. Although most of these tumors arise in the setting of gastric atrophy and hypergastrinemia, it is not understood what genetic background predisposes development of these ECL derived tumors. Moreover, diffuse microcarcinoids in the mucosa can lead to a field effect and limit successful endoscopic removal.

Objective

To define the genetic background that creates a permissive environment for gastric carcinoids using transgenic mouse lines. Design: The multiple endocrine neoplasia 1 gene locus (Men1) was deleted using Cre recombinase expressed from the Villin promoter (Villin-Cre) and was placed on a somatostatin null genetic background. These transgenic mice received omeprazole-laced chow for 6 months. The direct effect of gastrin and the gastrin receptor antagonist YM022 on expression and phosphorylation of the cyclin inhibitor p27Kip1 was tested on the human AGSE and mouse STC-1 cell lines.

Results

The combination of conditional Men1 deletion in the absence of somatostatin lead to the development of gastric carcinoids within 2 years. Suppression of acid secretion by omeprazole accelerated the timeline of carcinoid development to 6 months in the absence of significant parietal cell atrophy. Carcinoids were associated with hypergastrinemia, and correlated with increased Cckbr expression and nuclear export of p27Kip1 both in vivo and in gastrin-treated cell lines. Loss of p27Kip1 was also observed in human gastric carcinoids arising in the setting of atrophic gastritis.

Conclusion

Gastric carcinoids require threshold levels of hypergastrinemia, which modulates p27Kip1 cellular location and stability.

Keywords: Acid secretion, cancer genetics, endocrine tumors, gastrin, gastrin receptor

INTRODUCTION

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) develop primarily in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, pituitary, parathyroid, pancreas, and lungs, [1, 2, 3]. GI-NETs in the stomach are specifically labeled gastric carcinoids (GCs). GCs are relatively rare lesions representing about 23% of all GI-NETs [1]. Type I GCs (GC-I) represent approximately 70–80% of these NETs and are associated with chronic atrophic gastritis from primarily an autoimmune process or in rare instances Helicobacter pylori infection, [4]. Type II lesions (approximately 5–8% of GCs) occur with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES) primarily from gastrinomas with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1) mutations and to a lesser extent sporadic gastrinomas. About 20% of patients with GC-II due to ZES and MEN-1 develop aggressive lesions that metastasize, [5]. Both GC-I and GC-II are associated with hypergastrinemia, [1, 6]. By contrast, GC-III (14–25% of upper tract NETs) are characterized by normal serum gastrin levels, [7]. In response to food, antral G cells secrete gastrin, which binds to the cholecystokinin-B receptor (CCKBR) located on enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells to stimulate histamine release, [4, 8, 9, 10]. Subsequently, histamine stimulates acid secretion from parietal cells, [10, 11]. In addition to acid secretion, gastrin stimulates gastric epithelial cell proliferation, predominantly ECL cells that reside in the corpus, [12, 13, 14, 15, 16].

Animal models of GI-NETs available to study the genetic landscape leading to tumor development are lacking. Although the outbred African rodent Mastomys natalensis and some rat species spontaneously develop carcinoid tumors, [17, 18], their genetic background is ill-defined precluding definitive functional analysis of any mutations that contribute to tumor development. We previously reported that menin and somatostatin (Sst) inhibit gastrin expression, [19, 20]. Indeed, tissue-specific deletion of Men1 from the GI mucosa using Villin-Cre or Lgr5-Cre transgenes induces hypergastrinemia; however no gastrinomas were observed, [21], suggesting that additional mutations might be required. Since (Sst) stimulates menin gene expression in vitro, and both are inhibitors of gastrin, we hypothesized that combining the conditional deletion of Men1 with complete deletion of both Sst alleles might be sufficient to induce tumorigenesis. We report here that loss of both Men1 and Sst was sufficient to spontaneously generate gastric carcinoids in about 2 years or in 6 months with proton pump inhibition of acid secretion. We used this genetically defined animal model of GI-NETs to analyze the molecular events sufficient for gastric carcinoid development, and compare to the hallmarks of human gastric carcinoids.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human Samples

De-identified surgical samples of human gastric carcinoid from 2000 to 2015 were obtained from the University of Michigan Department of Pathology Surgical Slide Library (https://www.pathology.med.umich.edu/forms/lib_req). A pathologist who was blinded to the study graded and staged the tissue sections. The clinical information is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient demographics, tumor staging, and expression of CCKBR and p27Kip1

| Subject | Age | Gender | Diagnosis |

H. pylori |

CCKBR | p27Kip1 | Tumor Grade |

Tumor Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 34 | F | CAG | + | ++ | − | 1 | pT2 |

| 2 | 38 | F | CAG/IM | − | ++ | − | 1 | pT2 |

| 3 | 44 | M | CAG | − | +++ | − | 1 | pT2 |

CAG: Chronic Atrophic Gastritis

IM: Intestinal Metaplasia

Animals

Villin-Cre X Men1FL/FL (Men1ΔIEC) mice generated as described in, [21] were bred to somatostatin null (Sst−/−) mice (a gift from M. J. Low) to produce VC:Men1FL/FL; Sst−/− (Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/−) mice. The mice were genotyped using the following primers: Sst+/+ [5'-TGCGACAGGTGTTTAGCGGGC-3' (forward) and [5' AGCTTTGCGTT-CCCGGGGTG-3' (reverse)], Sst−/− [5' CTAAAGCGCAT-GCTCCAGAC-3' (forward) and 5'- AGCTTTGCGT-TCCCGGGGTG-3' (reverse)].

The mice were housed in a facility with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle with access to food and water ad libitum. Mouse genders used were equivalently distributed across the control and treatment groups (Supplementary Table 1). Experimental mice were fed omeprazole-laced chow (200 ppm, TestDiet, St. Louis, MO) for 6 months. Animal experiments were conducted according to protocols approved by the University of Michigan Committee on the Use and Care of Animals.

Cell culture

AGS cells stably-expressing the CCKBR (AGSE), a gift from Dr. Timothy Wang, Columbia University, [22] were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). STC-1 cells from a mouse intestinal tumor, [23, 24] were cultured in DMEM high glucose (with glutamine, without pyruvate) in 10% FBS.

Cells were plated onto 6-well plates (1×106), serum-starved in DMEM and treated with gastrin (Leu15 Gastrin I human, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 24h, with or without YM022 (Sigma). For peptone stimulated gastrin release experiments, STC-1 cells were treated with 2% peptone in glucose-free HBSS with 0.1% fatty acid free BSA for 2h. The media was collected for gastrin analysis by ELISA. The cells were lysed for protein assays.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from tissues using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) after DNase A digestion. cDNAs were synthesized using 500 ng of total RNA and the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Quantitative PCR (qPCRs) was carried out using a thermal cycler (model C1000, Bio-Rad) with Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) and SYBR Green dye (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA). PCR reactions were performed in duplicate using the following conditions: 95°C for 1 min, 39 cycles of 95°C for 9 s and 65°C for 1 min followed by 55°C for 1 min. The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Arbitrary units of the indicated mRNAs were normalized to Hprt mRNA and then were expressed as fold increase over untreated C57WT controls.

Western blot

Total cell proteins were obtained after homogenization in RIPA lysis buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) with the Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were obtained using the NE-PER kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Lysates were resolved on Novex® 4–20% Tris-Glycine gels (Life Technologies). Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes that were blocked in 5% BSA and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies (Supplementary Table 3). Protein signals were detected using the Odyssey Infrared System (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) after incubation with infrared dye-labeled secondary antibodies.

Immunohistochemistry

Stomachs of mice were fixed in 10% formaldehyde solution; paraffin embedded, and 5 µm sections were prepared. Sections were deparaffinized, protein blocked and stained with primary antibodies (Supplementary Table 3). For fluorescent detection, sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h (1:200 dilution). ProLong Gold antifade reagent with 4’, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Invitrogen) was used for nuclear counterstaining. Avidin-biotin complex (Vectastain Elite ABC Kit) and diaminobenzidine (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA) were used for detection using bright field microscopy. Images were taken using a Nikon inverted confocal microscope (Nikon Inc., NY) and Olympus BX53 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

AGSE and STC-1 cells were fixed for 20 min at room temperature (RT) in 4% paraformaldehyde, and then permeabilized for 5 min with 0.2% Triton X-100/PBS. After blocking with 1% donkey serum, cells were incubated with primary antibodies and stained as described above.

Plasma gastrin determination

Mice were fasted for 16 h before euthanization. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture and the plasma was collected by centrifugation. Gastrin levels were measured by the Human/Mouse/Rat Gastrin-I Enzyme Immunoassay Kit (RayBiotech Inc., GA, USA), according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Basal gastric acid content

Basal gastric acid content was determined as described previously [21], and data were normalized to mouse body weight.

Statistical analyses

All reported values are the mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA (GraphPad Prism 6, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Tukey’s method was applied for multiple comparisons after determination of significance by ANOVA. p <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Spontaneous development of Gastric Carcinoids in Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice

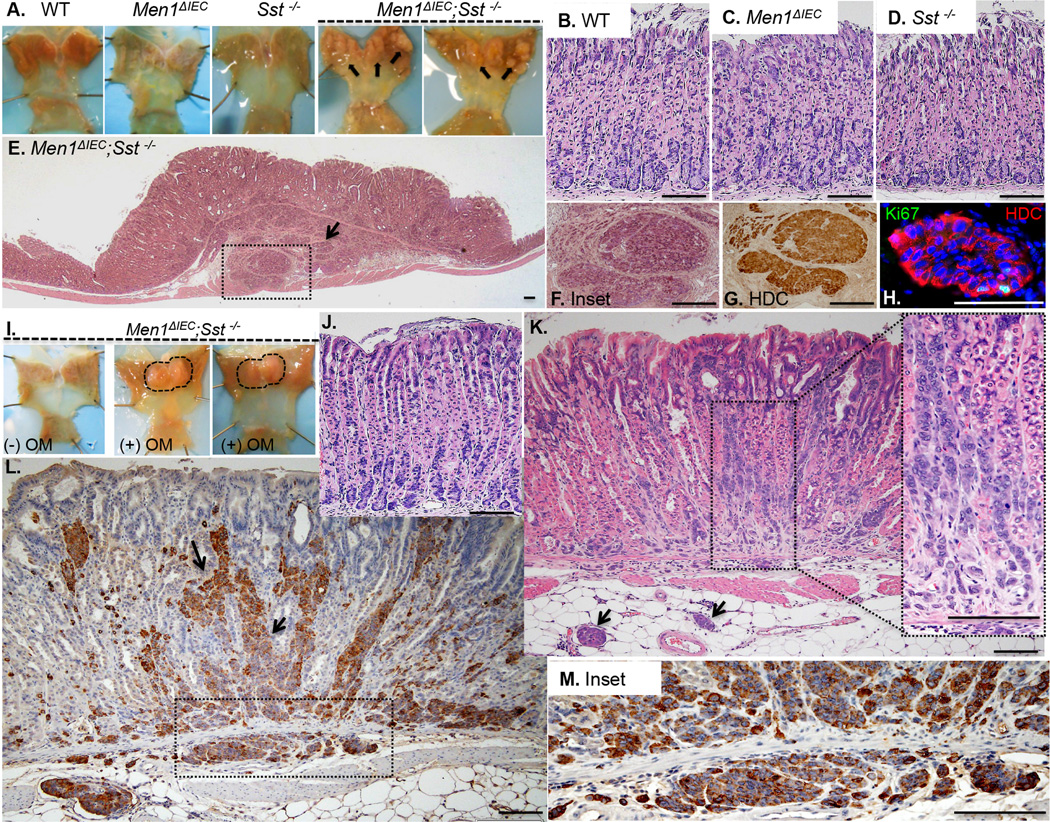

We previously reported that tissue-specific deletion of Men1 from the GI mucosa using the Villin-Cre driver (Men1ΔIEC) induces hypergastrinemia and epithelial hyperplasia; however no tumors were observed, [21], suggesting that additional mutations might be required for malignant transformation of neuroendocrine cells. Sst stimulates menin gene expression in vitro, [20] and both are known inhibitors of gastrin gene expression and secretion, [19, 20, 25]. Therefore we hypothesized that loss of both menin and Sst might be sufficient to induce tumorigenesis in neuroendocrine cells. To test this hypothesis, we bred the previously characterized Men1ΔIEC mouse line to Sst−/− mice to produce Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− chimeras. We observed that after about 2 years, Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice (n = 9/10) spontaneously developed polyps in the corpi of the stomach (figure 1A). Stomachs from age-matched C57BL/6 (WT), Men1ΔIEC, or Sst−/− mice did not develop polyps and there were no histologic changes (figure 1B–D). Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice showed corpus hyperplasia and tumors that infiltrated the submucosa and smooth muscle layers (figure 1E, F). H&E of the tumors revealed nests of mucosal and submucosal cells suggestive of endocrine tumors. The tumors were Hdc+ (figure 1G), and ChgA+ (Supplemental figure 1A), confirming their neuroendocrine origin, and showed rare Ki67+ cells (figure 1H). By 24 months, Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice were only modestly hypergastrinemic. G cell numbers and plasma gastrin levels were about 60% higher than WT mice (Supplemental figure 2). The number of HK-ATPase positive cells trended upwards in the Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice, reflecting an increase in the total number of parietal cells (Supplemental figure 3A–E). However, number of parietal cells per gland were not significantly different, (Supplemental figure 3F), probably due to a concomitant increase in overall gland size. Nevertheless, HK-Atpase mRNA and basal gastric acidity were not different among the four genotypes at 2 yrs (Supplemental figure 3G, H).

Figure 1. Gastric Carcinoid in Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice.

Stomachs from 23-month-old WT, Men1ΔIEC, Sst−/−, mice, showing polyps (arrows) in the corpi of two different Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice (A). H&E staining of WT (B), Men1ΔIEC (C), Sst−/− (D), and Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice (E, F) showing corpus hyperplasia and submucosal lesions in the latter. (G). DAB Immunohistochemistry for HDC of the area shown in F. (H). Immunofluorescent staining for Ki-67 and HDC in 23-month-old Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice. (I). Stomachs from 8–9 month old untreated (−OM) and omeprazole treated (+OM) Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice showing polyps (dotted lines) in the corpi. H&E staining of corpi of untreated (J) and omeprazole-treated Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice (K), showing hyperplasia and classical “salt and pepper nuclei” (arrows) in the latter. (L, M). DAB Immunohistochemistry for HDC in omeprazole-treated Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice. Scale bars: 100 µm.

Acid suppression accelerated carcinoid development to 6 months

Given the prolonged timeline to observe ECL cell hyperplasia and tumors, we sought to identify conditions that might accelerate tumor formation. Like the Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice, the African rodent Mastomys spontaneously develops gastric carcinoids in about 2 yrs [17, 18, 26]. However with acid suppression, these rodents develop gastric carcinoids in 4 mos [27]. Therefore we examined whether suppressing acid secretion accelerated tumor development in the Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice. Indeed after feeding omeprazole laced-chow for 6 mos, Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice (n = 8/10) developed polyps in the corpus as observed in the 2-year-old mice (figure 1I). Histochemical analysis showed linear cords of ECL cells that infiltrated the mucosa along with nodular aggregates in the submucosa (figure 1J). These lesions were also Hdc-positive cells (figure 1K, L) and ChgA (Suppl. Fig. 1B). No changes in morphology were observed with omeprazole treatment in the WT, Men1ΔIEC, or the Sst−/− mice (data not shown). Omeprazole feeding resulted in approximately a 60% decrease in basal gastric acid levels in all genotypes (Supplemental figure Fig. 4A); however no significant loss of parietal cells was observed (Supplemental figure Fig. 4B) suggesting that the observed phenotype is more likely due to loss of parietal cell function as opposed to physical loss of these cells.

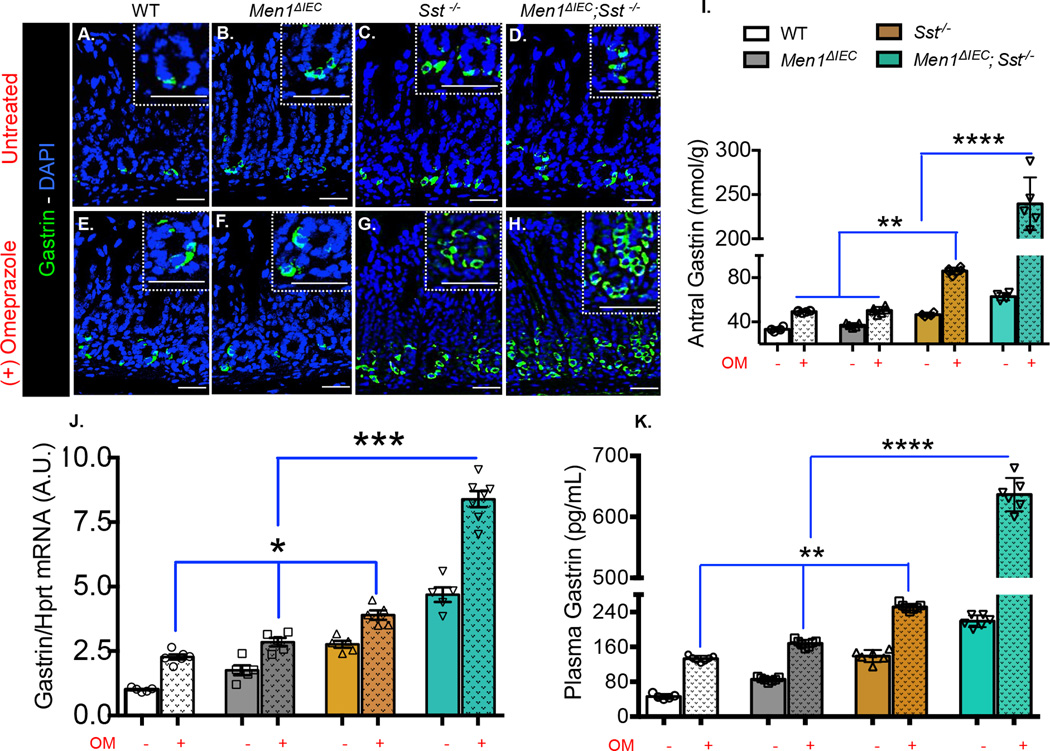

Carcinoid development required a threshold level of gastrin

To determine whether gastrin drives ECL tumor development, antral gastrin content and mRNA, and plasma gastrin levels were measured. Omeprazole treatment increased the number of gastrin-positive cells in all groups (figure 2A–H). To quantitate changes in expression, gastrin peptide was extracted from antral tissue and content was determined by ELISA. Omeprazole increased antral gastrin by approximately 2-fold in all genotypes (compared to respective untreated mice), except in the Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice, where a marked 4-fold increase in tissue gastrin was observed (figure 2I). In addition, gastrin mRNA levels increased by ~50% in all groups except in the Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice where a 2-fold increase was observed compared to untreated mice (figure 2J). Coincident with the increase in antral gastrin content and mRNA, omeprazole treatment significantly increased plasma gastrin levels in all groups with the highest induction (3-fold) occurring in the Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice (figure 2K). This suggested that a certain threshold level of gastrin was required before ECL hyperplasia and tumor formation was observed.

Figure 2. Markedly high gastrin levels in omeprazole treated Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice.

Immunofluorescent staining for gastrin in the antra of untreated WT (A), Men1ΔIEC (B), Sst−/− (C), and Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice (D), and mice treated with omeprazole for 6 months (E–H). (I). Antral gastrin content (nmol) from mice fasted for 16 hours normalized to tissue weight (n = 5–7). (J). Antral Gastrin mRNA expression measured by RT-qPCR normalized to Hprt mRNA (n = 5–8). (K). EIA measurement of gastrin concentration in circulating plasma from mice fasted for 16 h (n = 6–8). Shown are the Means ± SEM. * p< 0.05, ** p< 0.01, *** p< 0.001, **** p< 0.0001. Scale bars: 100 µm.

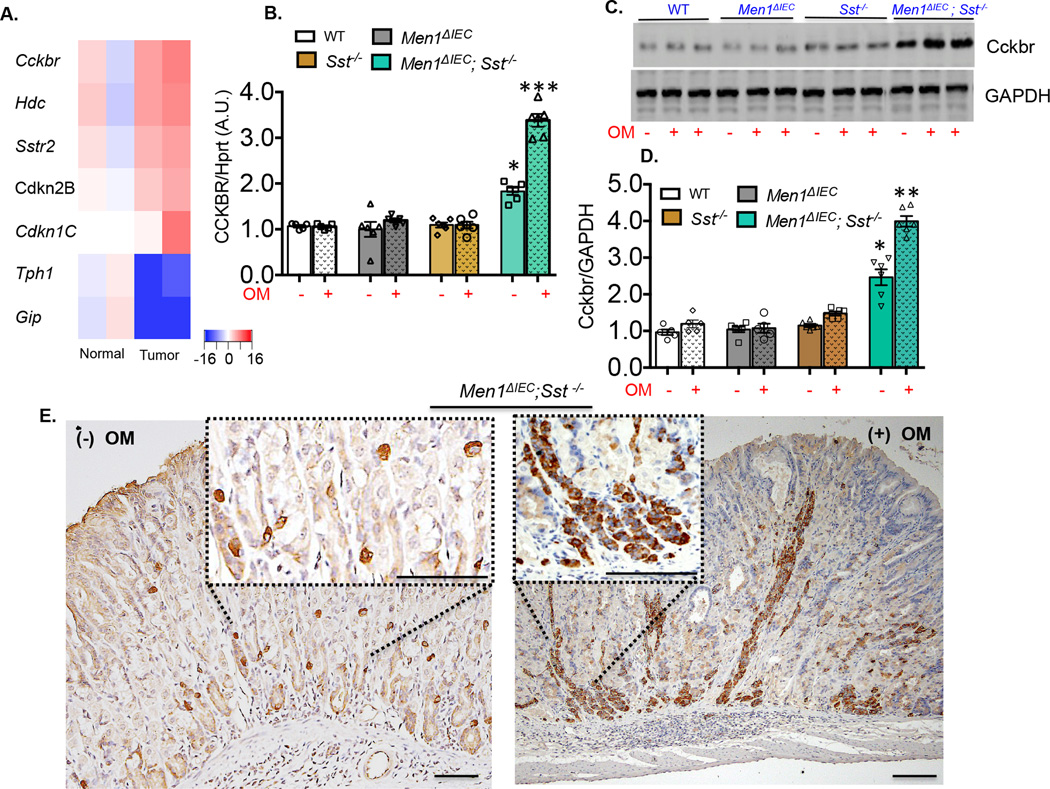

Hypergastrinemia induced Cckbr expression in carcinoid tumors

To identify the signaling pathways activated in the ECL tumors, we excised polyps from the corpi of Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice and performed a microarray analysis. As shown in the heat-map, there was a striking 16-fold increase in Cckbr expression observed in the polyps, compared to the adjacent visibly normal corpus areas from the same mouse (figure 3A). In addition, Hdc, somatostatin receptor 2 (Sstr2) and two transcriptionally regulated cyclin-dependent inhibitors were also induced (Cdkn2B and Cdkn1C) while other neuroendocrine markers, Tph1 and Gip were reduced. Cckbr is expressed on ECL cells, and is activated by circulating gastrin that stimulates their growth and proliferation [12, 13, 28]. The increase in tissue Cckbr mRNA observed on the microarray was validated by qPCR, western blot, and IHC (figure 3B–F). As shown in figure 3B, omeprazole treatment resulted in no significant changes in Cckbr mRNA levels in any of the groups except the Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice that exhibited a 75% increase in Cckbr mRNA in the absence of omeprazole and a nearly 2-fold increase with omeprazole. Although omeprazole treatment modestly increased gastrin expression in all genotypes, increased receptor expression was observed at a plasma gastrin above 250 pg/ml that was achieved only when both Men1 and Sst were deleted. Therefore, we concluded that a threshold level of hypergastrinemia was required to stimulate expression of its own receptor on ECL cells. Consistent with an increase in mRNA expression, there was a 4-fold increase in Cckbr protein in the polyps from omeprazole treated Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice versus a 2.5-fold increase in the untreated Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice compared to the other genotypes (figure 3C, D). In addition, examination of Cckbr expression by IHC showed significantly higher receptor density on the hyperplastic ECL cells (determined by HDC staining on serial sections) compared to adjacent visibly normal areas (figure 3E).

Figure 3. Increased Cckbr expression in Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice treated with omeprazole.

(A). Heat-map of transcripts generated from microarray analyses of RNA extracted from polyps and adjacent visibly normal areas of Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice (n=2). (B). Quantitation of Cckbr expression in treated and untreated WT, Men1ΔIEC, Sst−/−, and Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice, expressed as a ratio of mRNA from untreated WT controls, after normalization to Hprt. Shown are the Means ± SEM (n=5–8). (C). Representative immunoblot showing Cckbr protein levels (GAPDH used as loading control) in corpi of WT, Men1ΔIEC, Sst−/− mice and polyps isolated from Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice. (D). Quantitation of integrated band intensities analyzed using LICOR Odyssey software, expressed as a ratio to untreated WT controls, after normalization to GAPDH. Shown are the Means ± SEM (n=5–8). (E). Representative image of Cckbr expression determined by DAB staining in untreated and omeprazole-treated Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice. * p< 0.05, ** p< 0.01, *** p< 0.001. Scale bars: 100 µm.

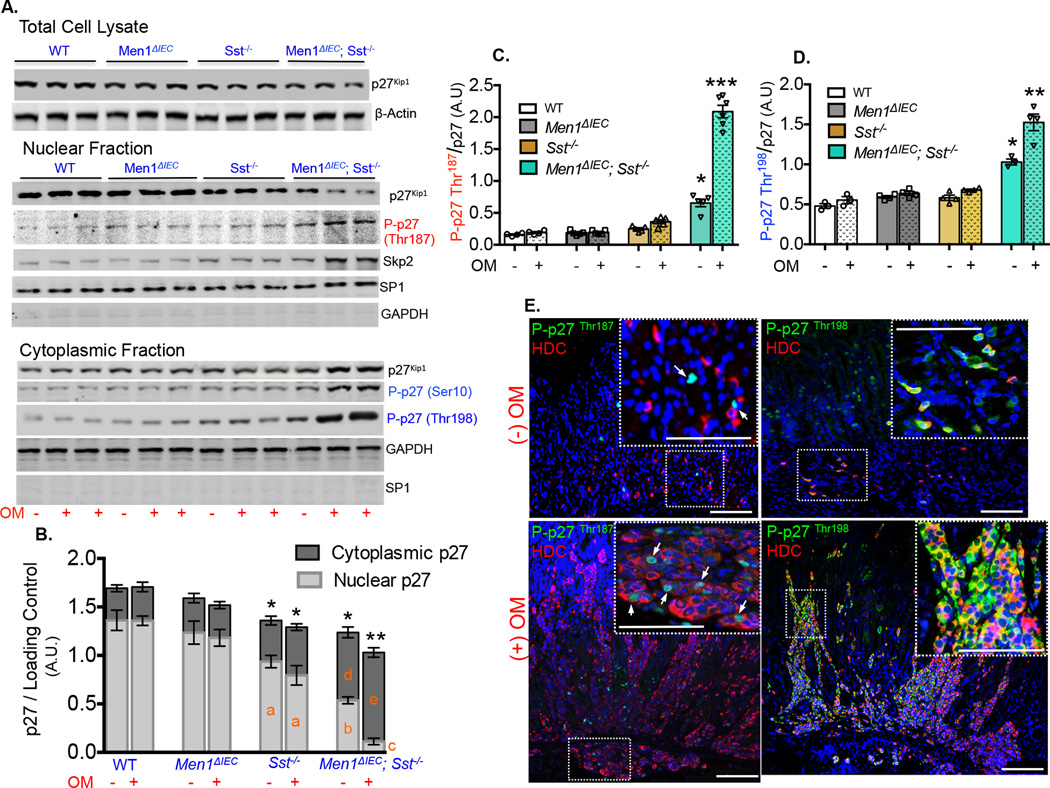

Increased Cckbr expression correlated with altered p27Kip1 expression and cellular localization

A critical pathway in the pathology of endocrine tumors is loss of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CDKI) expression, specifically p27Kip1, which contributes to uncontrolled proliferation and subsequent malignant transformation, [29, 30]. The MEN4 syndrome is due to germ line mutations in the CDKN1B locus, [31, 32]. To determine whether gastrin-driven carcinoids in our study correlated with p27Kip1 levels, we studied p27Kip1 protein expression in the polyps excised from omeprazole treated Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice. We observed a 30% decrease in total p27Kip1 levels in the omeprazole-treated mice that developed carcinoids, compared to omeprazole-treated WT mice (figure 4A, B). The effects were most significant in the Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− group, although a modest 15% decrease was observed in the Sst−/− mice that were unaffected after omeprazole treatment. Since p27Kip1 shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm, we isolated nuclear and cytosolic fractions from total cell lysates of polyps and examined protein expression in both fractions by Western Blot. No change in nuclear p27Kip1 expression was observed with omeprazole treatment in WT, or in the Men1ΔIEC mice (figure 4B). However, Sst deletion alone reduced nuclear p27Kip1 expression by ~30%, an effect that was enhanced when combined with deletion of Men1 (~60% reduction) and amplified by omeprazole (~92% reduction, figure 4A, B). Since the reduction in total p27Kip1 levels might be attributable to Skp2-mediated nuclear degradation following phosphorylation at Thr187, [33, 34, 35, 36] we first examined P-p27Thr187expression in nuclear lysates. A 200% increase in P-p27Thr187 expression was observed in the carcinoid tumors that correlated with higher Skp2 levels (figure 4A, C), suggesting increased degradation in the nucleus. Decrease in nuclear p27Kip1 levels was associated with a corresponding increase in the cytosolic fractions (figure 4A). Sst deletion alone resulted in approximately a 30% increase in the cytosolic p27Kip1 levels that was unaffected by omeprazole treatment. In contrast, combining Sst and Men1 deletion resulted in a 2-fold increase in cytosolic p27Kip1 that was increased 3-fold with omeprazole treatment (figure 4B). No changes were observed in the WT, or Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice. The increase in p27Kip1 in the cytoplasmic fraction was accompanied by accumulation of P-p27Ser10 (figure 4A, B). Phosphorylation of p27Kip1 at Ser10 facilitates its export from the nucleus to the cytoplasm where it either undergoes degradation, or is retained (blocking nuclear re-entry) after additional phosphorylation at Thr 198, [35]. Increased expression of P-p27Ser10 suggestive of accumulation prompted us to investigate P-p27Thr198 in the cytoplasmic pool. Indeed, a 3-fold increase in P-p27Kip1Thr198 expression was observed in carcinoid tumors (figure 4D). Since the polyps used to determine p27Kip1 expression could possibly be a heterogeneous mixture of different cell types, we examined changes in phosphorylated forms of p27Kip1 in ECL cells by immunofluorescence. We observed that Hdc+ cells are rarely P-p27Thr187 positive at baseline (no omeprazole); however a marked increase in expression was observed in the nuclei of omeprazole treated Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice (figure 4E) suggesting accelerated degradation. More interestingly, a dramatic increase in cytosolic P-p27Thr198 expression (figure 4E) was observed in ECL cell tumors, indicating cytoplasmic retention of p27Kip1. Consistently, total p27 expression in untreated Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice was predominantly nuclear in Hdc+ cells (Supplemental figure 5A) while increased cytoplasmic expression was observed in the omeprazole treated counterparts (Supplemental figure 5B). Taken together, our data demonstrates that carcinoid formation is associated with loss of nuclear p27Kip1, it’s export to and retention in the cytoplasm.

Figure 4. Carcinoids are associated with altered p27Kip1 expression.

(A) Representative blot showing total p27Kip1 expression in cellular lysates from corpi of untreated, or omeprazole-treated WT, Men1ΔIEC, Sst−/−, and polyps isolated from Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice (β-Actin loading control). Representative blots showing total p27Kip1, P-p27Thr187 and Skp2 protein expressions in nuclear fraction (SP1 loading control); P-p27Ser10 and P-p27Thr198 in cytoplasmic fraction (GAPDH loading control). Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were prepared as described earlier and fraction purity was assessed using appropriate markers (nuclear fraction showed negligible GAPDH expression, and cytoplasmic fraction had negligible SP1 levels). (B). Quantitation of p27Kip1 expression in in nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, expressed as integrated band intensities normalized to appropriate loading controls (n=4–5). Letters (a–e) denote significant differences in nuclear and cytoplasmic p27Kip1 expressions compared to that of respective cellular fractions in untreated WT controls. Bars with different letters are significantly different from each other. Asterisk symbols denote significant differences in total cellular p27Kip1 expressions compared to that in untreated WT controls. Bars with different asterisk symbols are significantly different from each other. Quantitation of P-p27Thr187 expression in nuclear fraction (C), and P-p27Thr198 expression in cytoplasmic fraction (D) expressed as ratio of total p27Kip1, after normalization to SP1, and GAPDH loading controls, respectively (n=4–6). Shown are the Means ± SEM. * p< 0.05, ** p< 0.01, *** p< 0.001. (E). Immunofluorescent staining for P-p27Thr187, P-p27Thr198 (arrows), and Hdc in the corpi of untreated or omeprazole-treated Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice. Scale bars: 50 µm.

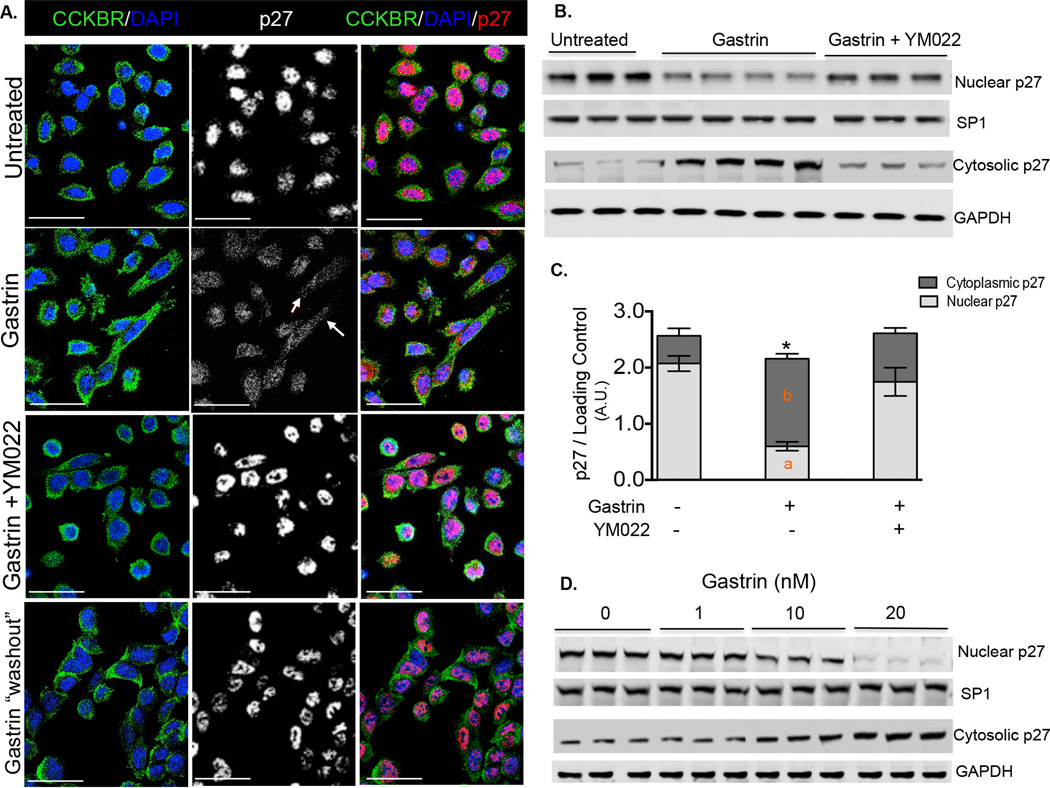

Gastrin exported p27Kip1 from the nucleus in vitro

To directly test whether the observed effects on Cckbr and p27Kip1 were mediated by gastrin, we treated human gastric AGSE cells with gastrin peptide for 24 h, and examined changes in CCKBR and p27Kip1 expression by immunohistochemistry and western blotting. Immunostaining showed that gastrin treatment lead to increased CCKBR expression (figure 5A). p27Kip1 was predominantly nuclear in untreated cells; while treatment with gastrin led to a 70% decrease in the nuclear compartment and a 3-fold increase in the cytoplasmic fraction (figure 5A–C). Treatment with the CCKBR inhibitor YM022 or removal of gastrin from the media reversed the observed effects, demonstrating that nuclear export of p27Kip1 and its retention in the cytoplasm are dependent on canonical gastrin signaling. To further confirm whether the effects observed were specific to gastrin, AGSE cells were treated with increasing concentrations of gastrin and nuclear and cytoplasmic levels of p27Kip1 were examined. Interestingly, gastrin induced a dose-dependent decrease in p27Kip1 that was associated with a concomitant increase in the cytoplasmic pool (figure 5D). To determine whether the observed gastrin-mediated effects occurred in enteroendocrine cells, we repeated the above experiments using the mouse enteroendocrine STC-1 cell line. Indeed, increased Cckbr expression and nuclear export of p27Kip1 was observed with only 5 nM gastrin (Supplemental figure 6A). Since STC-1 cells are known to release endogenous gastrin in response to stimuli, we further tested whether 2% peptone stimulated subsequently regulates p27Kip1. Peptone induced a time-dependent response in gastrin secretion, which was unaffected by YM022 inhibitor (Supplemental figure 6B). This result confirmed that peptone-induced gastrin secretion is not mediated through the gastrin receptor. A robust increase in CCKBR expression was observed that was associated with loss of nuclear p27Kip1 and its accumulation in the cytoplasm; whereas, the YM022 inhibitor blocked these effects. It should be noted that only 5 nM gastrin was sufficient to observe effects in STC-1 cells, compared to AGSE cells that required at least 10 nM, perhaps due to the ability of STC-1 cells to generate endogenous gastrin. Taken together our data demonstrate that chronic gastrin stimulation induces expression of its own receptor that subsequently exports p27Kip1 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm where it is retained. Loss of nuclear p27Kip1 subsequently creates a permissive environment for uncontrolled environment (Supplemental figure 6C).

Figure 5. Gastrin induces CCKBR expression and nuclear export of p27Kip1 in human AGSE cells.

(A). Immunofluorescent staining of CCKBR and total p27Kip1 (p27) in AGSE cells treated with or without 20 nM gastrin, in the presence and absence of 10 nM YM022 for 24 hours, and after removal of gastrin from the culture media. (B). Representative blot showing total p27Kip1 in nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of AGSE cells treated with or without 20 nM gastrin, in the presence and absence of 10 nM YM022 for 24 hours. (C). Quantitation of total p27Kip1 expression in nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of AGSE cells treated with or without gastrin and YM022. Shown are the Means ± SEM (n = 3 experiments). * p< 0.05. Letters (a, b) denote significant differences in nuclear and cytoplasmic p27Kip1 expressions compared to respective cellular fractions in untreated cells (without gastrin or YM022). Asterisk denotes significant differences in total cellular p27Kip1 expressions compared to that in untreated cells. (D). Representative blot showing total p27Kip1 expression in nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of AGSE cells treated without or with 1, 10, and 20 nM gastrin. Scale bars: 20 µm.

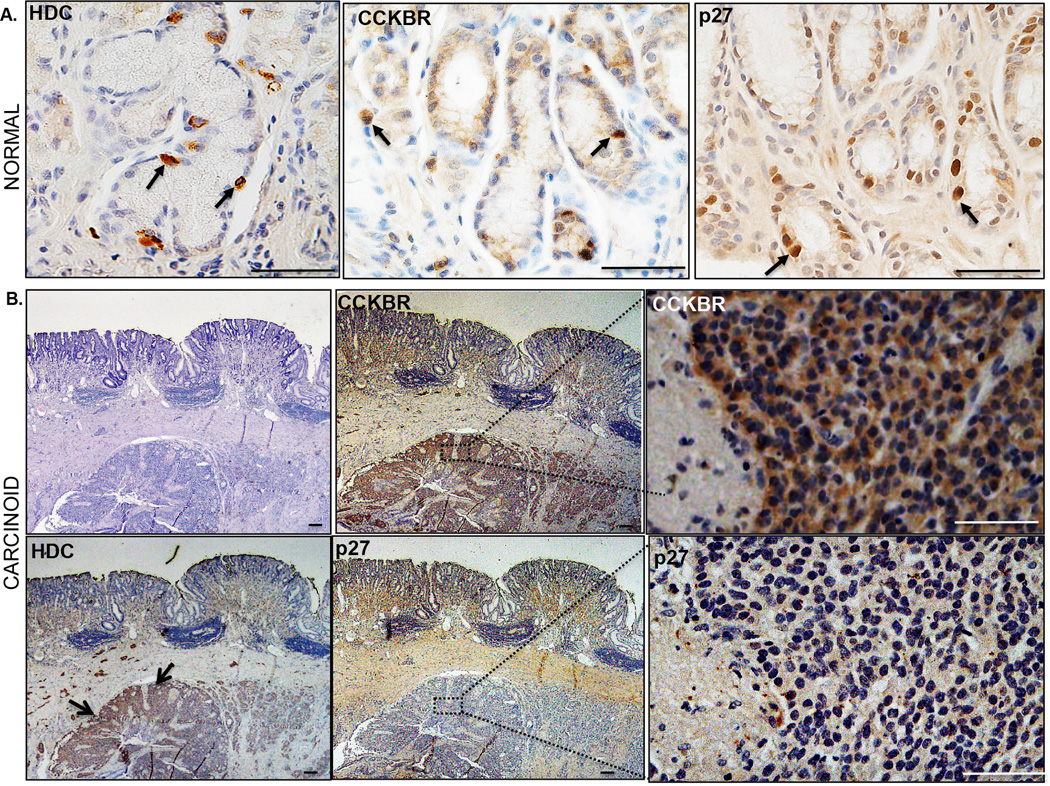

Increased Cckbr expression and loss of p27Kip1 in human gastric carcinoids

Archived surgical specimens from patients were obtained to examine CCKBR and p27Kip1 expression in human gastric carcinoids. A total of 3 patients with chronic atrophic gastritis and gastric carcinoids were obtained (Table 1). Consistent with our animal model, all specimens contained nests of HDC+ cells confirming ECL cell tumor origin. HDC+ cell clusters exhibited robust CCKBR protein expression and significant reduction in total p27Kip1 expression (figure 6A, B). Since it is likely that the human tumors developed over several years, possibly decades, we speculate that the initial signaling events leading to p27Kip1phosphorylation were a proximal event and that much of p27Kip1 has been degraded, which contributed to tumor formation.

Figure 6. Increased CCKBR expression and loss of p27Kip1 in human gastric carcinoids.

DAB Immunohistochemistry for HDC, CCKBR, and p27Kip1 in normal human stomach (A) and archived surgical specimens from gastric carcinoid patients (B). Scale bars: 20 µm.

DISCUSSION

Although rare, gastric carcinoid tumors can arise in the setting of chronic atrophic gastritis and subsequent hypergastrinemia, [37, 38]. However, it is not understood what predisposes individuals to carcinoid development in the stomach. Prior outbred rodent models have shown that gain-of-function mutations in the Cckbr receptor create a genetic landscape that results in carcinoid development within 2 years, [39, 40]. We demonstrate in the current study that gastric carcinoids arise once a threshold level of hypergastrinemia is achieved in mice carrying deletions of both Men1 and Sst loci. Sst regulates gastrin at the level of gene expression and peptide secretion, [25]. In addition, Sst induces menin gene expression that inhibits gastrin gene expression, [20]. Thus, we concluded that these two loci function synergistically to suppress gastrin. Moreover, it has been previously reported in cell culture models that gastrin stimulates the expression of its own receptor, [13]. Therefore the effect of sustained hypergastrinemia amplifies Cckbr signaling in part through its ability to increase the density of Cckbr on responding cells. Based on the intensity of immunohistochemical staining relative to the remaining mucosa, ECL cells appear to exhibit a higher density of gastrin receptors and as a result would be more susceptible to the proliferative effects of the circulating hormone.

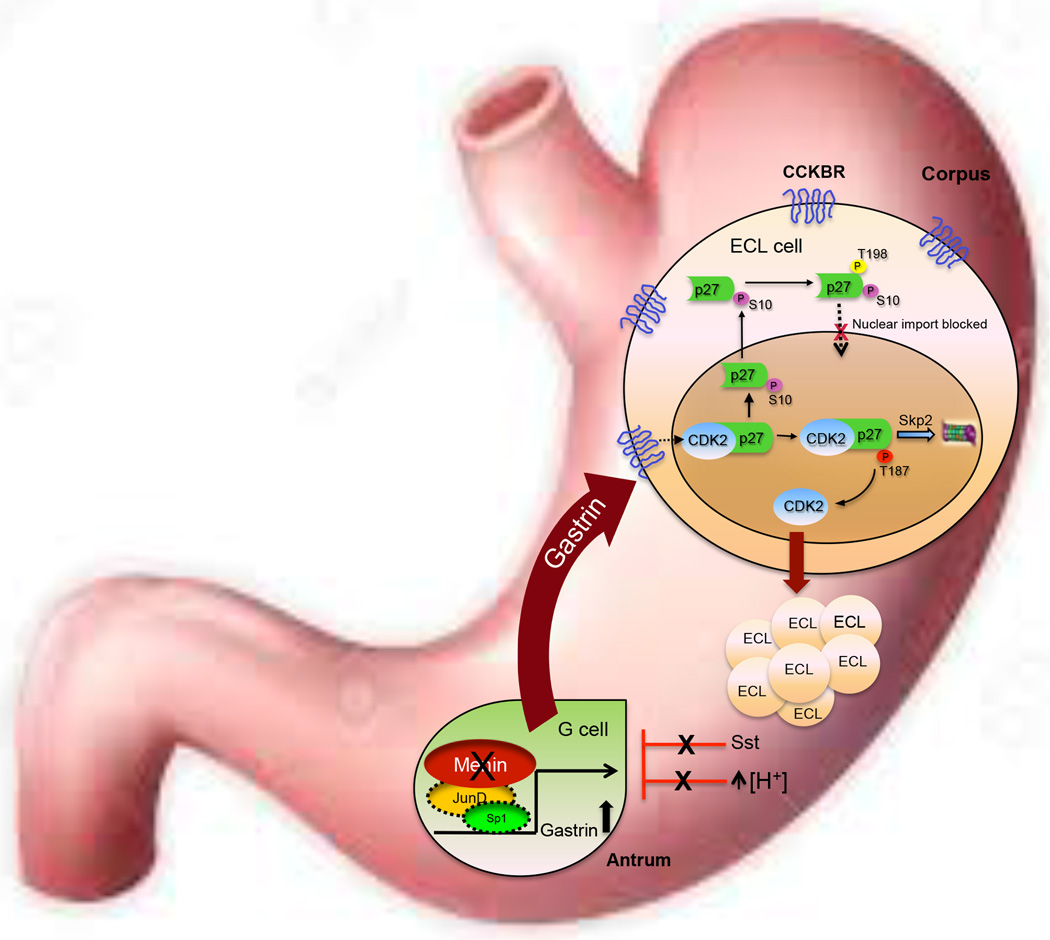

Having established in vivo that there was an increase in both gastrin and then Cckbr, we examined a mechanism by which hypergastrinemia stimulates ECL cell hyperplasia. It is known that many endocrine tumors are susceptible to reduced levels or function of p27Kip1, a cyclin-dependent inhibitor, [30, 41, 42, 43]. In fact, the MEN4 syndrome in human subjects is due to germline mutations in the CDKN1B (p27Kip1) locus, [31]. Therefore we stained both mouse and human gastric carcinoids for p27Kip1 and found that there was a loss of nuclear p27Kip1 with coincident accumulation in the cytoplasm where it has been reported to be oncogenic, [35]. We speculate that loss of nuclear levels is in part attributable to cytoplasmic and nuclear degradation as evidenced by the appearance of P-p27Thr187 and increased Skp2 expression. Skp2 levels are higher in cancers of the prostate, [44], lung, [45, 46], pancreas, [47], and colon, [45, 48]. Dose-dependent p27Kip1 translocation in AGSE and STC-1 cell lines that express CCKBR revealed that changes in cellular p27Kip1 levels and location occurred in response to its gastrin-mediated phosphorylation. Activation of the CCKBR initiates a cascade of signal transduction events that include an increase in intracellular calcium as well as the induction of protein kinase activity such as protein kinase C, Map kinases and Jak2/Stat3/PI3K/Akt, [49, 50]. Presumably, phosphorylation of p27Kip1 in the nucleus due to nuclear kinase activity is ultimately what regulates the fate of this cyclin-dependent inhibitor. Thus, like the human tumors, hypergastrinemia in mice increased Cckbr expression, which modulated p27Kip1 protein stability and localization leading to ECL cell hyperplasia and eventually carcinoids (figure 7).

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of proposed mechanism for ECL cell hyperplasia and carcinoid formation.

Men1 mutations have been reported in gastric carcinoids and are perhaps one of several mechanisms predisposing human subjects to hypergastrinemia, [6]. It is known that inactivating mutations in Men1 also creates a genetic landscape suitable for gastrinomas, but it is not understood what creates the preference for ECL versus G cell hyperplasia. Acid suppression was required to induce carcinoid formation in our model in addition to the deletion of Men1 and Sst, underscoring the impact an environmental trigger can exert on a permissive genetic environment. This combination of events might explain why patients on omeprazole rarely develop carcinoids – their lack of genetic predisposition.

Our data further confirms that deletion of Men1 alone does not favor carcinoid development, but rather cooperates with additional loci, e.g., deletion of Sst. The study demonstrated that mutation of only two loci was sufficient to converge upon the cellular signals regulating gastrin gene expression and secretion, which subsequently elevated Cckbr expression and altered p27Kip1 localization, events critical for gastric carcinoid development. Since the mutation in Men1 was required to generate the phenotype, we conclude that our transgenic mouse model most closely mimics Type 2 GI-NETs, but awaits detailed analysis of relevant sites, e.g., the duodenum and pancreas for evidence of gastrin-expressing cells. Upper GI-NETs are rare, and currently there are no mouse models available to better analyze NET pathogenesis or to test emerging therapies before proceeding to human trials. This is the first mouse model that faithfully recapitulates GC phenotype, thereby allowing pre-clinical testing approaches in the future. In summary, we define here in mechanistic terms how hypergastrinemia promotes the development of gastric NETs. Furthermore, the propensity to develop ECL hyperplasia reported here uncovers the potential for therapeutic targets, e.g., specific Cckbr-dependent kinase pathways targeting p27Kip1, which can be tested to treat gastrin-dependent carcinoid tumors.

Supplementary Material

(A). Immunofluorescent staining for CgA in corpi of 23 month old WT, Men1ΔIEC, Sst−/−, and Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice. (B). Immunofluorescent staining for CgA in corpi of 8–9 month old untreated or omeprazole treated Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice. Scale bars: 100 µm

Immunofluorescent staining for gastrin in the antra of 23-mo-old WT (A), Men1ΔIEC (B), Sst−/− (C), and Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice. (D). Morphometric analysis of gastrin-positive cells in the antra (E); values are numbers of gastrin-immunostained cells per high power field (400× magnification). Shown are the Means ± SEM (n = 4–6). (F). EIA measurement of gastrin concentration in circulating plasma from mice fasted for 16 h. Shown are the Means ± SEM (n = 4–5). *p< 0.05, ** p< 0.01, *** p< 0.001, **** p< 0.0001. Scale bars: 100 µm

Immunofluorescent staining for HK-ATPase in the corpi of 23-mo-old WT (A), Men1ΔIEC (B), Sst−/− (C), and Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice (D). Morphometric analysis of HK-ATPase positive cells (E, F); values are number of HK-ATPase+ cells per 100× field (E), and normalized to area of tissue using Image J software (F; n = 4–8). (G) Gastric corpus HK-ATPase mRNA expression measured by RT-qPCR normalized to Hprt mRNA (n = 3–8). (H). Basal gastric acid levels in 23-mo-old fasted mice measured by base titration. Shown are the Means ± SEM (n = 4–5). *p< 0.05. Scale bars: 100 µm

(A). Immunofluorescent staining for HK-ATPase in the corpi of untreated and omeprazole-treated Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice. (B). Basal gastric acid levels in untreated and omeprazole-treated mice (n = 5–7) measured by base titration. *** p< 0.001.

Immunofluorescent staining for total p27Kip1 and HDC in the corpi of untreated (A), or omeprazole-treated Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice (B). Scale bars: 50 µm.

(A). Immunofluorescent staining of CCKBR and total p27Kip1 (p27) in STC-1 cells treated with or without 20 nM gastrin, in the presence and absence of 10 nM YM022 for 24 hours, and after removal of gastrin from the culture media. (B). EIA measurement of gastrin released in media of STC-1 cells with or without 2% peptone in the presence or absence of YM022 inhibitor for 30 and 60 minutes. Shown are the Means ± SEM (n = 2 experiments). * p< 0.05, ** p< 0.01. Asterisk denotes significant differences in gastrin released in media compared to that in untreated cells (without peptone or YM022). Bars with different asterisk symbols are significantly different from each other. (C). Immunofluorescent staining of CCKBR and total p27Kip1 (p27) in STC-1 cells treated with or without 2% peptone, in the presence and absence of 10 nM YM022 for 2 hours.

Summary Box.

What is already known about this subject?

Type 1 and type 2 gastric carcinoids develop in response to hypergastrinemia.

The genetic basis for type 1 gastric carcinoids is largely unknown.

Some gastric carcinoid tumors contain MEN1 mutations.

The functional significance of known mutations is ill defined.

What are the new findings?

A mouse model of gastric carcinoid was genetically engineered and demonstrated synergy between at least two gene loci—Men1 and somatostatin.

Synergy between Men1 and somatostatin loci was required to achieve a threshold level of hypergastrinemia after augmentation by omeprazole, suggesting a possible genetic predisposition.

Hypergastrinemia induced phosphorylation of the CDKN1B gene product p27Kip1, which promoted its translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm.

Loss of p27Kip1 was observed in human gastric carcinoids with atrophic gastritis.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

Avoiding proton pump inhibitors in patients with atrophic gastritis.

Provides additional molecular evidence to support the clinical use of CCKBR inhibitors in patients with type I and 2 gastric carcinoid prior to using somatostatin agonists, e.g., octreotide.

Consider trials of Skp2 and p27Kip1 inhibitors for type I and 2 gastric carcinoid.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the University of Michigan Microscopy and Image Analysis Core, for assistance with tissue processing, embedding, staining, and access to the confocal microscope; and the DNA Sequencing Core for performing microarray analyses. We are grateful to Jill C. Todt and Amanda Photenhauer for valuable technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH Grant R37 DK45729 (to JLM) and P30 DK 034933 Digestive Disease Center Molecular core facility (Michigan Gastrointestinal Research Center).

Abbreviations

- Villin-Cre

transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase from the villin promoter

- Men1

multiple endocrine neoplasia 1

- Men1ΔIEC

homozygous deletion of Men1 locus using Villin-Cre recombinase

- Sst

somatostatin

- Hdc

histamine decarboxylase

- Chga

chromogranin A

- Cdkn1b

p27Kip1

- Cckbr

cholecystokinin b receptor = gastrin receptor

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.S. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. A.K. assisted with IHC and IF staining. M.M.H. maintained and genotyped the mouse colony. E.K.C. interpreted the histologic analysis and staging of the human tumors. J.L.M. designed the study, assisted with data analysis, critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. S.S. and J.L.M. are the guarantors of this work and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of data analysis. All authors have read and approve of the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burkitt MD, Pritchard DM. Review article: Pathogenesis and management of gastric carcinoid tumours. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1305–1320. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilligan CJ, Lawton GP, Tang LH, West AB, Modlin IM. Gastric carcinoid tumors: the biology and therapy of an enigmatic and controversial lesion. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:338–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meeker A, Heaphy C. Gastroenteropancreatic endocrine tumors. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;386:101–120. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakke I, Qvigstad G, Sandvik AK, Waldum HL. The CCK-2 receptor is located on the ECL cell, but not on the parietal cell. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:1128–1133. doi: 10.1080/00365520152584734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norton JA, Melcher ML, Gibril F, Jensen RT. Gastric carcinoid tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia-1 patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome can be symptomatic, demonstrate aggressive growth, and require surgical treatment. Surgery. 2004;136:1267–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibril F, Schumann M, Pace A, Jensen RT. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: a prospective study of 107 cases and comparison with 1009 cases from the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004;83:43–83. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000112297.72510.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massironi S, Zilli A, Conte D. Somatostatin analogs for gastric carcinoids: For many, but not all. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:6785–6793. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i22.6785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helander HF, Wong H, Poorkhalkali N, Walsh JH. Immunohistochemical localization of gastrin/CCK-B receptors in the dog and guinea-pig stomach. Acta Physiol Scand. 1997;159:313–320. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1997.114360000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prinz C, Kajimura M, Scott DR, et al. Histamine secretion from rat enterochromaffinlike cells. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:449–461. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90719-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waldum HL, Sandvik AK, Brenna E, Petersen H. Gastrin-histamine sequence in the regulation of gastric acid secretion. Gut. 1991;32:698–701. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.6.698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hakanson R, Sundler F. Histamine-producing cells in the stomach and their role in the regulation of acid secretion. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1991;180:88–94. doi: 10.3109/00365529109093183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asahara M, Kinoshita Y, Nakata H, et al. Gastrin receptor genes are expressed in gastric parietal and enterochromaffin-like cells of Mastomys natalensis. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:2149–2156. doi: 10.1007/BF02090363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashurst HL, Varro A, Dimaline R. Regulation of mammalian gastrin/CCK receptor (CCK2R) expression in vitro and in vivo. Exp Physiol. 2008;93:223–236. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.040683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen D, Zhao CM, Al-Haider W, et al. Differentiation of gastric ECL cells is altered in CCK(2) receptor-deficient mice. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:577–585. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hakanson R, Tielemans Y, Chen D, et al. Time-dependent changes in enterochromaffin-like cell kinetics in stomach of hypergastrinemic rats. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:15–21. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryberg B, Tielemans Y, Axelson J, et al. Gastrin stimulates the self-replication rate of enterochromaffinlike cells in the rat stomach. Effects of omeprazole, ranitidine, and gastrin-17 in intact and antrectomized rats. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:935–942. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90610-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oettle AG. Spontaneous carcinoma of the glandular stomach in Rattus (mastomys) natalensis, an African rodent. Br J Cancer. 1957;11:415–433. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1957.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snell KC, Stewart HL. Malignant argyrophilic gastric carcinoids of Praomys (Mastomys) natalensis. Science. 1969;163:470. doi: 10.1126/science.163.3866.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mensah-Osman E, Labut E, Zavros Y, et al. Regulated expression of the human gastrin gene in mice. Regul Pept. 2008;151:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mensah-Osman E, Zavros Y, Merchant JL. Somatostatin stimulates menin gene expression by inhibiting protein kinase A. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295:G843–G854. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00607.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veniaminova NA, Hayes MM, Varney JM, Merchant JL. Conditional deletion of menin results in antral G cell hyperplasia and hypergastrinemia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G752–G764. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00109.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raychowdhury R, Fleming JV, McLaughlin JT, Bulitta CJ, Wang TC. Identification and characterization of a third gastrin response element (GAS-RE3) in the human histidine decarboxylase gene promoter. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297:1089–1095. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02345-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grant SG, Seidman I, Hanahan D, Bautch VL. Early invasiveness characterizes metastatic carcinoid tumors in transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 1991;51:4917–4923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rindi G, Grant SG, Yiangou Y, et al. Development of neuroendocrine tumors in the gastrointestinal tract of transgenic mice. Heterogeneity of hormone expression. Am J Pathol. 1990;136:1349–1363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bachwich D, Merchant J, Brand SJ. Identification of a cis-regulatory element mediating somatostatin inhibition of epidermal growth factor-stimulated gastrin gene transcription. Mol Endocrinol. 1992;6:1175–1184. doi: 10.1210/mend.6.8.1357547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soga J. Pathological analysis of spontaneous carcinogenesis in glandular stomach of Praomys (Mastomys) natalensis. Acta Med Biol (Niigata) 1968;15:181–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poynter D, Selway SA. Neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia and neuroendocrine carcinoma of the rodent fundic stomach. Mutat Res. 1991;248:303–319. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(91)90064-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen D, Zhao CM, Norlen P, et al. Effect of cholecystokinin-2 receptor blockade on rat stomach ECL cells. A histochemical, electron-microscopic and chemical study. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;299:81–95. doi: 10.1007/s004419900136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doganavsargil B, Sarsik B, Kirdok FS, Musoglu A, Tuncyurek M. p21 and p27 immunoexpression in gastric well differentiated endocrine tumors (ECL-cell carcinoids) World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6280–6284. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i39.6280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim HS, Lee HS, Nam KH, Choi J, Kim WH. p27 Loss Is Associated with Poor Prognosis in Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Cancer Res Treat. 2014;46:383–392. doi: 10.4143/crt.2013.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pellegata NS, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Siggelkow H, et al. Germ-line mutations in p27Kip1 cause a multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome in rats and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15558–15563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603877103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiedemann T, Pellegata NS. Animal models of multiple endocrine neoplasia. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carrano AC, Eytan E, Hershko A, Pagano M. SKP2 is required for ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the CDK inhibitor p27. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:193–199. doi: 10.1038/12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sutterluty H, Chatelain E, Marti A, et al. p45SKP2 promotes p27Kip1 degradation and induces S phase in quiescent cells. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:207–214. doi: 10.1038/12027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vervoorts J, Luscher B. Post-translational regulation of the tumor suppressor p27(KIP1) Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3255–3264. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8296-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vlach J, Hennecke S, Amati B. Phosphorylation-dependent degradation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27. EMBO J. 1997;16:5334–5344. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bordi C, D'Adda T, Azzoni C, Pilato FP, Caruana P. Hypergastrinemia and gastric enterochromaffin-like cells. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19(Suppl 1):S8–S19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burkitt MD, Varro A, Pritchard DM. Importance of gastrin in the pathogenesis and treatment of gastric tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1–16. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schaffer K, McBride EW, Beinborn M, Kopin AS. Interspecies polymorphisms confer constitutive activity to the Mastomys cholecystokinin-B/gastrin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28779–28784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.28779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang LH, Luque EA, Efstathiou JA, et al. Gastrin receptor expression and function during rapid transformation of the enterochromaffin-like cells in an African rodent. Regul Pept. 1997;72:9–18. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(97)01025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grabowski P, Schrader J, Wagner J, et al. Loss of nuclear p27 expression and its prognostic role in relation to cyclin E and p53 mutation in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7378–7384. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lidhar K, Korbonits M, Jordan S, et al. Low expression of the cell cycle inhibitor p27Kip1 in normal corticotroph cells, corticotroph tumors, and malignant pituitary tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3823–3830. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.10.6066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rahman A, Maitra A, Ashfaq R, et al. Loss of p27 nuclear expression in a prognostically favorable subset of well-differentiated pancreatic endocrine neoplasms. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;120:685–690. doi: 10.1309/LPJB-RGQX-95KR-Y3G3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Z, Gao D, Fukushima H, et al. Skp2: a novel potential therapeutic target for prostate cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1825:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hershko DD. Oncogenic properties and prognostic implications of the ubiquitin ligase Skp2 in cancer. Cancer. 2008;112:1415–1424. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Timmerbeul I, Garrett-Engele CM, Kossatz U, et al. Testing the importance of p27 degradation by the SCFskp2 pathway in murine models of lung and colon cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14009–14014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606316103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schuler S, Diersch S, Hamacher R, et al. SKP2 confers resistance of pancreatic cancer cells towards TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Int J Oncol. 2011;38:219–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shapira M, Ben-Izhak O, Linn S, et al. The prognostic impact of the ubiquitin ligase subunits Skp2 and Cks1 in colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:1336–1346. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dockray GJ, Moore A, Varro A, Pritchard DM. Gastrin receptor pharmacology. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14:453–459. doi: 10.1007/s11894-012-0293-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu W, Chen GS, Shao Y, et al. Gastrin acting on the cholecystokinin2 receptor induces cyclooxygenase-2 expression through JAK2/STAT3/PI3K/Akt pathway in human gastric cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2013;332:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A). Immunofluorescent staining for CgA in corpi of 23 month old WT, Men1ΔIEC, Sst−/−, and Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice. (B). Immunofluorescent staining for CgA in corpi of 8–9 month old untreated or omeprazole treated Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice. Scale bars: 100 µm

Immunofluorescent staining for gastrin in the antra of 23-mo-old WT (A), Men1ΔIEC (B), Sst−/− (C), and Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice. (D). Morphometric analysis of gastrin-positive cells in the antra (E); values are numbers of gastrin-immunostained cells per high power field (400× magnification). Shown are the Means ± SEM (n = 4–6). (F). EIA measurement of gastrin concentration in circulating plasma from mice fasted for 16 h. Shown are the Means ± SEM (n = 4–5). *p< 0.05, ** p< 0.01, *** p< 0.001, **** p< 0.0001. Scale bars: 100 µm

Immunofluorescent staining for HK-ATPase in the corpi of 23-mo-old WT (A), Men1ΔIEC (B), Sst−/− (C), and Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice (D). Morphometric analysis of HK-ATPase positive cells (E, F); values are number of HK-ATPase+ cells per 100× field (E), and normalized to area of tissue using Image J software (F; n = 4–8). (G) Gastric corpus HK-ATPase mRNA expression measured by RT-qPCR normalized to Hprt mRNA (n = 3–8). (H). Basal gastric acid levels in 23-mo-old fasted mice measured by base titration. Shown are the Means ± SEM (n = 4–5). *p< 0.05. Scale bars: 100 µm

(A). Immunofluorescent staining for HK-ATPase in the corpi of untreated and omeprazole-treated Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice. (B). Basal gastric acid levels in untreated and omeprazole-treated mice (n = 5–7) measured by base titration. *** p< 0.001.

Immunofluorescent staining for total p27Kip1 and HDC in the corpi of untreated (A), or omeprazole-treated Men1ΔIEC; Sst−/− mice (B). Scale bars: 50 µm.

(A). Immunofluorescent staining of CCKBR and total p27Kip1 (p27) in STC-1 cells treated with or without 20 nM gastrin, in the presence and absence of 10 nM YM022 for 24 hours, and after removal of gastrin from the culture media. (B). EIA measurement of gastrin released in media of STC-1 cells with or without 2% peptone in the presence or absence of YM022 inhibitor for 30 and 60 minutes. Shown are the Means ± SEM (n = 2 experiments). * p< 0.05, ** p< 0.01. Asterisk denotes significant differences in gastrin released in media compared to that in untreated cells (without peptone or YM022). Bars with different asterisk symbols are significantly different from each other. (C). Immunofluorescent staining of CCKBR and total p27Kip1 (p27) in STC-1 cells treated with or without 2% peptone, in the presence and absence of 10 nM YM022 for 2 hours.