Short abstract

After inadvertently making an unauthorised protocol deviation, two researchers were left with a weakened study and feeling disillusioned

Research governance is designed to ensure that “health and social care research is conducted to high scientific and ethical standards.”1 Currently the same process is applied to all breaches, regardless of their severity or likely implications. Although we do not deny the importance and relevance of research governance, our experience leads us to question how it is applied.

What we did

Our project, funded through a small grant from the trust, explored the effect of several variables on outcome in a day therapy service for eating disorders. Our outcome measures comprised several questionnaires administered at three monthly intervals to clients with eating disorders. As a result of advice from our project steering group (a necessary requirement for such projects), we agreed to introduce a simple qualitative measure to balance the fact that our original protocol used only quantitative measures. We used an interview based on a standard questionnaire (the Morgan and Russell scale2) but adapted to form a semistructured interview covering quality of life areas such as social contacts, relationships, family, and employment.

The reason for the study becoming subject to the research governance process was that we incorporated this improvement into the protocol without informing the assistant research and development director or local research ethics committee and without adding it to the patient information and consent forms. We were unaware of the requirement to do this and were not told that it was necessary. However, we have been told that in future researchers will be formally notified of this requirement.

What happened

The transgression emerged during a routine telephone conversation with the assistant research and development director. Immediately, we were asked to stop all our research activities while our protocol deviation was subjected to the research governance procedures. This involved three months of formal meetings with the assistant research and development director, resubmission of the protocol and associated patient information and consent forms, and amendments to the application to the ethics committee (15 copies required). We also had to write letters to the ethics committee and the assistant research and development director explaining where we had gone wrong and the amendments made. Furthermore, all other projects in the unit were subjected to a lengthy audit process. To restart the project we had to formally request permission from the assistant director.

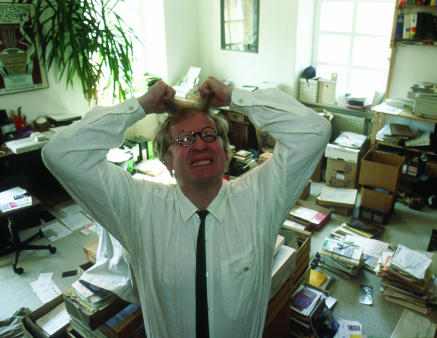

Figure 1.

Credit: GERD PFEIFFER/VOLLER ERNST/SOA

After effects

This process had a major effect on the study. The research was frozen for two months, during which time patients left the service and could not be followed up and other patients joined the service and could not be incorporated into our project. Moreover, ongoing monitoring of patients in the project (weekly measures of self rated motivation) could not be obtained. This has left us with incomplete datasets and an overall loss of patient numbers, which is critical for statistical analysis. These deficiencies affected the validity of our overall results and waste the efforts of both patients and researchers.

The two month freeze also had financial implications. The research assistant's time was not used for the project during that time. This meant a net loss of one sixth of her overall time allocated to the project amounting to a cost of just under £1000. Costs were also incurred for our time to conduct all the research governance procedures and the time of the ethics committee.

The process put us under a lot of stress, and we felt that something shameful and wrong had occurred. It was suggested, for example, at one point that our error had to be treated in the same way as giving the wrong drug to a cancer patient. Clearly, this was not realistic.

Completing the reparative activities as requested was time consuming and competed with other pressing clinical demands. Moreover, we felt that the reparation was excessive in relation to the problem identified. The process felt arbitrary and punitive; it bore no obvious relation to the simple, creative idea that had instigated it. We both felt demoralised and angry about the process and less inclined to undertake research in the future.

Reflections and recommendations

In our case, the research governance process seems an over-reaction to a small, technical infringement of the procedures. Its effect was to destroy the very thing it was designed to protect—the quality of the research. We believe that the research governance process itself carries with it ethical implications. Is it ethical to waste the time of patients and staff and taxpayers' money? Is it ethical to destroy the results of a sound research project? Just as we would not expect a surgeon to be stopped halfway through a successful operation on a patient, so we consider good research should be allowed to be completed and not interfered with unnecessarily.

Summary points

The process of research governance does not take into account the type of transgression

This can result in a heavy handed approach for minor problems

The process carries with it ethical implications—for example, loss of researchers' time, impairments in the quality of data collected

Research governance needs to be governed more closely

The research governance process needs to be governed more closely, so that it is only correctly applied where research requires it, and the process modified accordingly to the “deviation” identified. As Glasziou and Chalmers write regarding ethics review, we need to challenge the “one size fits all” approach.3

Editorial by Warlow

Contributors and sources: AMJ has research interests in service evaluation and eating disorders. She has several publications on eating disorders. BB was co-researcher in the study and responsible for administration, collation of data, and clinical interviews. AMJ is guarantor.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Medical Research Council. Policy and procedure for inquiring into allegations of scientific misconduct. London: MRC, 1997.

- 2.Morgan HGP, Hayward AE. Clinical assessment of anorexia nervosa: the Morgan-Russell outcome assessment schedule. Br J Psychiatry 1998;152: 367-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glasziou P, Chalmers I. Ethics review roulette: what can we learn? BMJ 2004;328: 121-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]