Dear Editor-in-Chief

In this paper, we report the effect of high-intensity intermittent training (HIIT) program on mood state in overweight/obese young men. Obesity is widespread worldwide associated with increased risk of health issues such as cardio-respiratory diseases, type 2 diabetes and cancer (1). It is also associated with psychological and social hazards. Indeed, obese people often suffer of low self-esteem, loneliness, sadness, and nervousness, which are key symptoms of depression (2). HIIT consists of vigorous exercise performed at high intensity for a brief period of time interposed with recovery intervals at low-to-moderate intensity or complete rest. This type of exercise was shown to improve physical fitness (3), but its effect on psychological factors has not been sufficiently explored.

Twenty young male students, aged 18.2±1.01 yr were included and divided based on body mass index (BMI) in overweight/obese group (OG; BMI>25 kg/m2, n=10) and normal-weight group (NWG, BMI<25 kg/m2, n=10). The training program was designed for 8 wk, 3 sessions per week. After 20 min warm-up, participants underwent a series of 30 sec run at 100%–110% of maximal aerobic velocity (MAV) interspersed by periods of active recovery of 30 sec run at 50% of MAV. The increase in training load was ensured during the 3rd and 4th wk by increasing the number of repetitions and an increase in the intensity of the work. Mood states were evaluated before and after the program training using a validated psychometric test; the Profile of Mood States questionnaire (POMS) (4). The POMS is a self-evaluation questionnaire assessing five negative moods: tension-anxiety, depression-dejection, anger-hostility, fatigue-inertia, confusion-bewilderment and one positive mood; vigor-activity. Total Mood Disorder (TMD) score was calculated using the formula; TMD= (tension+depression+anger+fatigue+confusion)-vigor (4).

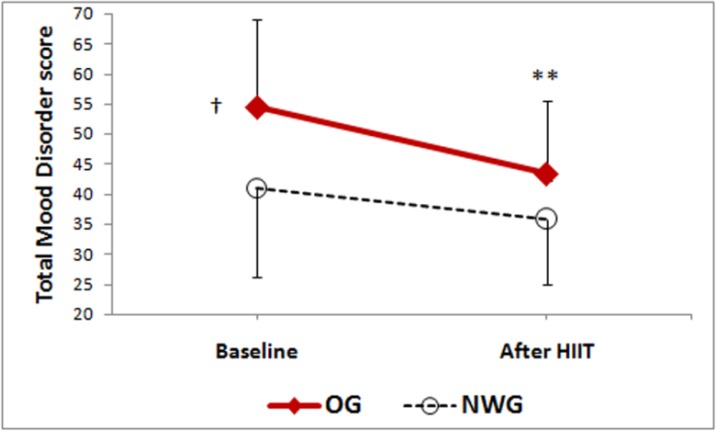

At inclusion, the TMD score and tension sub-scale score were significantly higher (P=0.05) in OG than NWG, but other items of POMS were similar in the two groups. Eight-wk of HIIT program resulted in a significant decrease in the score of negative moods tension (15.3±2.71 to 13.4±1.90, P=0.020) and depression (18.9±5.55 to 17.7±4.99, P=0.018) in OG. The vigor sub-scale score has increased in both groups (19.0±3.97 to 21.5±2.68 in OG, P=0.023; and 19.3±3.62 to 21.2±3.49 in NWG, P=0.012). After the completion of HIIT program, TMD score has significantly decreased in OG (P=0.004) but not in NWG (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1:

Variation of Total mood disorder (TMD) score of the Profile of mood state (POMS) in overweight/obese (OG) and normal-weight (NWG) young men after high-intensity intermittent training (HIIT) program; **, p<0.01 [compared to basal values in overweight/obese group (OG)]; †, p<0.05 [compared to basal values in normal-weight group (NWG)].

Physical activity is assumed to have a beneficial effect on psychological status and mental health (5). It reduces anxiety, depression, and negative mood and improves self-esteem and cognitive functioning (6). The mechanisms by which physical activity carries influence on mood are not entirely understood. However, the emotional boost may be explained by an interaction of psychological and physiological mechanisms. The possible psychological mechanisms include improvement of self-efficacy, distraction, mastery and social integration (7). The beneficial effect on mood state may also be explained by physiological secretion of neuroendocrine factors such as monoamines, endorphins and endocabannoids in response to physical exercise (8). The study showed a better improvement of moods in over-weight/obese compared to normal-weight subjects. Such findings are understandable as the mood state is mostly altered in obese people. Furthermore, the concomitant weight loss is an additional factor that may contribute to the improvement of the mood state in obese subjects (9). In our study, the positive effect of short HIIT program on mood state in overweight/obese subjects was accompanied by a feeling of satisfaction at the end of program. These participants suggested ensuring continuity of the training.

Intermittent training could be used as a means to improve the physical and psychological health and upgrade the quality of life in over-weight/obese individuals. Further research is required to identify the mechanisms responsible for the improvement of mood state in over-weight/obese young men after HIIT.

Acknowledgments

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH. (2009). The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and over-weight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 9: 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Strauss RS. (2000). Childhood obesity and self-esteem. Pediatrics, 105 ( 1): e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kessler HS, Sisson SB, Short KR. (2012). The potential for high-intensity interval training to reduce cardio-metabolic disease risk. Sports Med, 42 ( 6): 489–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF. (1992). EITS Manual for the Profile of Mood States. San Diego: Educational and Industrial Testing Service. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kanning M, Schlicht W. (2010). Be active and become happy: an ecological momentary assessment of physical activity and mood. J Sport Exerc Psychol, 32 ( 2): 253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Callaghan P. (2004). Exercise: a neglected intervention in mental health care? J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs, 11 ( 4): 476–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Paluska SA, Schwenk TL. (2000). Physical activity and mental health: current concepts. Sports Med, 29 ( 3): 167–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heyman E, Gamelin FX, Goekint M, Piscitelli F, Roelands B, Leclair E, et al. (2012). Intense exercise increases circulating endocannabinoid and BDNF levels in humans—possible implications for reward and depression. Psych Neuroendocrinol, 37 ( 6): 844–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Annesi JJ. (2008). Relations of mood with body mass index changes in severely obese women enrolled in a supported physical activity treatment. Obes Facts, 1 ( 12): 88–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]