Abstract

Until the mid-nineteenth century, life expectancy at birth averaged 20 years worldwide, owing mostly to childhood fevers. The germ theory of diseases then gradually overcame the belief that diseases were intrinsic. However, around the turn of the twentieth century, asymptomatic infection was discovered to be much more common than clinical disease. Paradoxically, this observation barely challenged the newly developed notion that infectious diseases were fundamentally extrinsic. Moreover, interindividual variability in the course of infection was typically explained by the emerging immunological (or somatic) theory of infectious diseases, best illustrated by the impact of vaccination. This powerful explanation is, however, best applicable to reactivation and secondary infections, particularly in adults; it can less easily account for interindividual variability in the course of primary infection during childhood. Population and clinical geneticists soon proposed a complementary hypothesis, a germline genetic theory of infectious diseases. Over the past century, this idea has gained some support, particularly among clinicians and geneticists, but has also encountered resistance, particularly among microbiologists and immunologists. We present here the genetic theory of infectious diseases and briefly discuss its history and the challenges encountered during its emergence in the context of the apparently competing but actually complementary microbiological and immunological theories. We also illustrate its recent achievements by highlighting inborn errors of immunity underlying eight life-threatening infectious diseases of children and young adults. Finally, we consider the far-reaching biological and clinical implications of the ongoing human genetic dissection of severe infectious diseases.

Keywords: human genetics of infectious diseases, primary immunodeficiency, inborn errors of immunity, pediatrics, immunity to infection

INTRODUCTION: THREE COMPLEMENTARY THEORIES

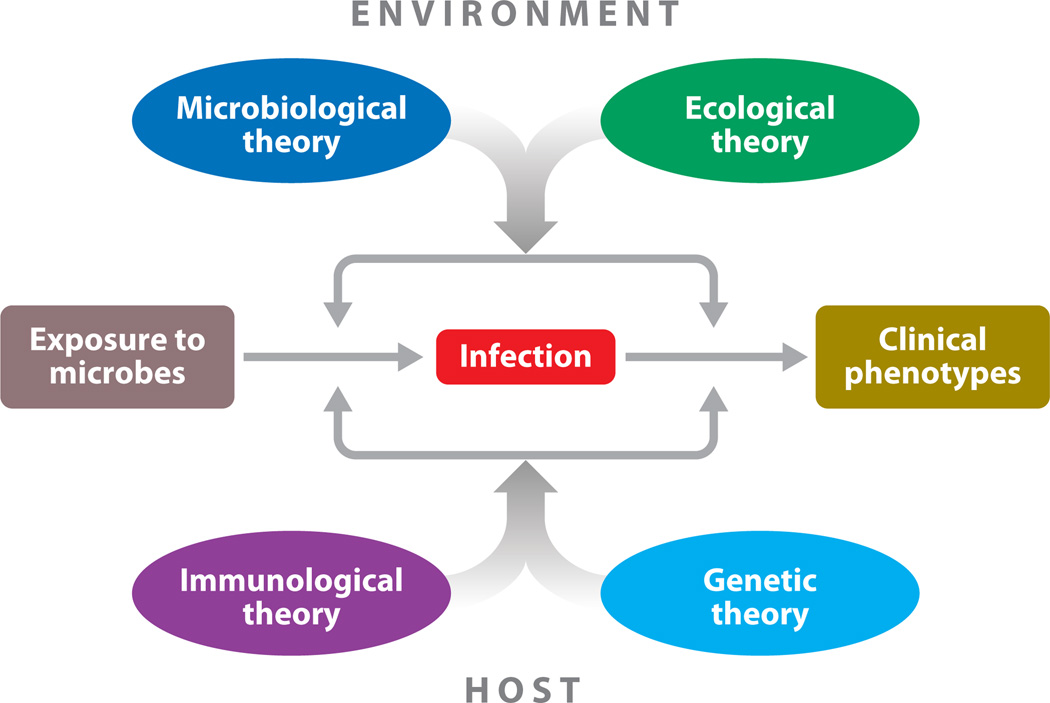

The fundamental enigma in the field of infectious disease is the tremendous clinical variability between individuals in the course of infection (Figure 1). Various theories attribute this clinical variability to different sources: microbial variability in the microbiological theory, environmental variability (not including that of the pathogen considered but potentially including that of other microbes) in the ecological theory, somatic immunity variability (adaptive and acquired) in the immunological (or somatic) theory, and germline immunity variability (intrinsic, innate, and adaptive immunity) in the genetic theory. We discuss here the genetic theory of infectious diseases, focusing in particular on its development and achievement in the context of the well-established microbiological and immunological theories. By concentrating on these three theories, we do not mean to underplay the importance of the ecological theory, as neatly illustrated by the impact of dual infections (16, 50, 154).

Figure 1.

The four complementary theories of infectious diseases. In principle, interindividual variability of clinical presentation (ranging from asymptomatic to lethal infection) in infected individuals can depend on four sets of overlapping forces, corresponding to the microbiological, ecological, immunological, and genetic theories. Disease is attributed to microbial variation (qualitative or quantitative) in the microbiological theory; to environmental variation (other than for the pathogen concerned) in the ecological theory; to a deficiency of acquired somatic, adaptive immunity (both genetic and epigenetic elements) in the immunological theory; and to inborn errors of germline-encoded immunity (whether intrinsic, innate, or adaptive) in the genetic theory. These four theories are both complementary and overlapping.

We should also emphasize that the apparently competing microbiological, ecological, immunological, and genetic theories are actually not only complementary but also overlapping. For example, the immunological theory refers to somatic processes, which remain under the control of the germline; the genetic theory is a germline theory of immunity; and the ecological theory often involves innate or adaptive immune responses. Nevertheless, the idea that human germline genetic variability governs the development of clinical infectious diseases has occasionally met with some resistance from both microbiologists and immunologists, albeit for different reasons; it has faced less opposition from ecologists. This idea has, however, gained ground over the past century, with growing support from human geneticists and clinicians in particular. Before reviewing the historical reasons underlying these misunderstandings and some of the achievements supporting the genetic theory, we first briefly consider resistance to this theory.

Most microbiologists would probably agree that human genetic variants may be associated with infectious diseases (for predisposition or resistance), and would even accept the possibility of causal genetic determinism (with complete or even only high penetrance). Those sympathetic to this idea, however, often see it as consisting of a small series of exceptions rather than as a notion for which proof of principle has been established. Some remain reluctant to think that this genetic determinism might become a general paradigm. Microbiologists tend to favor the notion of a multitude of risk factors (e.g., economic status, hygiene, age), including human genetic variability, so long as all these risk factors, including those of a genetic nature, are individually associated with but not causative of disease or the lack thereof (56).

Paradoxically, this opinion is shared by some human geneticists who have been influenced not only by microbiologists but also by the history of population genetics, which does not always sit easily with the notion of biological determinism. From Karl Pearson’s early studies to the recent polygenic model of “common variant, common disease,” there is a long history of human genetic studies compatible with the dominant view of microbiologists (33, 71–73). In contrast, from Archibald Garrod onward, some human geneticists have tried to decipher the molecular and cellular determinism of infectious diseases by first dissecting the “disease-causing” human genetic lesions (3, 5, 27–29, 31). This approach has given rise to the hypothesis that there is almost always a morbid human genotype underlying the infectious disease in each patient, an idea that itself is intellectually rooted in Garrod’s groundbreaking notions of “chemical individuality” and “inborn errors of metabolism” and the ensuing idea that infectious diseases may deterministically result from “inborn errors of immunity” (12, 62, 63). The proponents of a strict human genetic theory see the microbe as no more than an environmental trigger, like phenylalanine, the nutrient triggering clinical symptoms in patients with phenylketonuria (97). We have previously proposed the uchronia that Darwin’s reading of Mendel may have led him to suggest that his own marriage to a cousin would account for the subsequent loss of three of his ten children owing to a fever of autosomal recessive inheritance (2).

This view, however, remains largely speculative, and it is not without reason that most micro-biologists remain firmly focused on microbes. Understandably, they see the microbe as the main (if not the only) cause of infectious diseases, the main actor in a cast of thousands, with each of the latter playing a modest individual role in pathogenesis and acting as a foil for the microbe. Most would agree with Stanley Falkow (54), who even emphasized that “it is imperative when pursuing the genetic analysis of bacterial pathogenesis to apply some molecular form of Koch’s postulates.” As we argue below, however, the study of microbial pathogenesis has been somewhat hindered by Koch’s postulates, if one considers that inborn errors of the host are key determinants of most, if not all, human infectious diseases, and are as necessary for the disease’s development as the microbes themselves.

The resistance of some immunologists to a human genetic theory of infectious diseases is more difficult to decipher. Geneticists and immunologists could be seen as having separately proposed competing theories of infectious diseases, with only the immunological theory having reached the status of a paradigm. This is partly because the genetic theory was developed outside the immunological community—principally by population and clinical human geneticists and plant and animal geneticists—three or four decades after the immunological theory. Louis Pasteur (120) had established the immunological theory as early as 1881, well before the first formulation of the genetic theory, which followed the discovery of asymptomatic infections in the first two decades of the twentieth century (63, 123). Garrod (63) best expressed the problem faced by geneticists in the 1930s, when he noted in his book The Inborn Factors in Disease that “it is, of necessity, no easy matter to distinguish between immunity which is inborn and that which has been acquired.” Indeed, immunology rapidly yielded an acquired (i.e., somatic and adaptive) theory of infectious diseases, with genetic and epigenetic components. The T and B cell adaptive responses—their specificity, diversity, memory, and plasticity—can all be largely accounted for in somatic terms, whether genetic [e.g., variable-diversity-joining (VDJ) recombination] or epigenetic (e.g., cytokine polarization) in nature, and this can certainly account for interindividual variability in the course of many infections, as best illustrated by the success of vaccinations from 1881 onward (119). It is widely accepted that if half a population is vaccinated against a disease, most if not all individuals with that disease will belong to the other half.

With such a solid immunological theory of infectious diseases, the mechanisms of which have been elegantly dissected by academics over the past century and the practical implications of which have been successfully exploited by industry, it is not without reason that some immunologists do not perceive the need for a complementary human germline genetic theory. However, adaptive immunity is genetically controlled, and a number of observations, such as vaccination failure in some individuals, provide support for a genetic theory of reactivation and secondary infections as a complement to the immunological theory. Perhaps more important, the immunological theory best fits reactivation and secondary diseases, and its relevance may be limited to these diseases. It cannot easily account for interindividual variability in the course of natural primary infections, which typically occur in childhood (although this is not always the case) and against which vaccination provides the only protection (or, more rarely, cross-protection). Nevertheless, most immunologists would agree with Charles Janeway (78), who wrote, “Unfortunately, defects in innate immunity though very rare are almost always lethal. They are rarely observed in a physician’s office, unlike defects in adaptive immunity, and only appeared once the wonder drug penicillin became available to treat infections. Therefore, we have relatively few patients surviving the lack of one or the other of their innate immune mechanisms, and thus we have relatively little data on the role of the innate immune system from such patients.” As we argue below, however, inborn errors of innate immunity are common and are more harmful collectively than individually, and—precisely unlike defects of adaptive immunity—they were not masked before the advent of antibiotics.

BRIEF HISTORY OF THE FIELD

The misunderstandings between microbiologists, immunologists, and geneticists stem from the historical schools of thought regarding the dreadful problem of childhood fever and death. It is thus useful to briefly review the history of the field of infectious diseases, including, in particular, the paradoxical and mind-boggling discovery that the same infectious agent can cause lethal fever in one child and asymptomatic infection in another. Attempts to resolve this conundrum have led to seemingly conflicting, but actually overlapping and perfectly complementary, solutions based on host immunological (somatic) and genetic (germline) theories. This brief introduction to the history of infectious diseases (Figures 2 and 3) provides a rational basis for collaborative, comprehensive, fruitful approaches to the continual threat to humanity and living organisms, animals and plants alike, posed by existing, emerging, and reemerging microbes.

Figure 2.

Historical perspective of the pathogenesis of infectious diseases (1800–1950). The development of physiology and pathology in the early nineteenth century (Antoine Lavoisier, François Magendie, Claude Bernard), which opposed vitalism and were based on physics and chemistry, understandably led to the view that diseases were intrinsic. Compelling experimental evidence established the role of microbes (from Louis Pasteur to Robert Koch), leading to the germ theory of infectious diseases (~1870) in the most extraordinary paradigm shift ever seen in medicine. The subsequent discovery, at the turn of the twentieth century, that asymptomatic infection is much more common than disease for almost all microbes (Charles Nicolle, ~1915) only marginally modified the almost universal and deeply rooted, although only recently acquired, perception that infectious diseases are fundamentally extrinsic. Moreover, interindividual variability in the course of infection was rapidly and easily explained by the emerging immunological theory, resulting in a somatic, acquired, immunological theory of infectious diseases (from Louis Pasteur to Paul Ehrlich), best illustrated by the impact of vaccinations (Louis Pasteur, 1881). The complementary idea that human germline genetic variation could account for disease development, particularly for childhood infections lethal in the course of primary infection, was proposed early on by distinguished pioneers such as Archibald Garrod with the concept of inborn errors of immunity (~1930), the first demonstration of which was provided in the early 1950s by the descriptions of the first primary immunodeficiency (by Ogden Bruton and others) and of the protective role of the sickle cell trait against severe malaria (by Anthony Allison and others).

Figure 3.

Historical perspective of the genetic theory of infectious diseases (1950–2010). We highlight eight inborn errors of immunity underlying infectious diseases that, in our view, neatly illustrate the explanatory power of a human genetic theory of childhood infectious diseases. Four are population based (blue text): protection against severe malaria (HbS trait, HBB mutation); Mendelian resistance to common Plasmodium vivax (DARC mutation) infection and to human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) (CCR5 mutation) infection; and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) clearance, spontaneously or with treatment, by common variants (IL28B polymorphisms). The other four are patient based (green text): primary immunodeficiencies and multiple infections [e.g., X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA), the first described primary immunodeficiency] and selective Mendelian susceptibilities to Epstein-Barr virus [X-linked lymphoproliferative disease (XLP)], mycobacteria [Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial diseases (MSMD)], and herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) [herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE)] infections. The discovery of inborn errors of immunity has greatly accelerated over the past decade, owing particularly to the tremendous progress in genetic technologies.

1768–1867: Toward a Germ Theory of Diseases

Since the dawn of humanity, the most formidable problem ravaging its numbers has been childhood fever, which frequently led to death. Life expectancy at birth did not exceed 20–25 years worldwide for at least the past 10,000 years (and probably much longer, back to the origins of humans) (23). Mortality by the age of 15 was approximately 50% in the past 10,000 years, and fever was by far the main cause of childhood death, killing many more than war and famine. There were, of course, many types of fever, but the physicians could hardly come up with accurate descriptions and a proper nosology until the rise of the clinical-pathological paradigm in Parisian hospitals at about the time of the French Revolution (92).

These initial descriptions did not touch on the question of whether fever and disease were intrinsic or extrinsic. Paradoxically, the concomitant physiological revolution initiated by Antoine Lavoisier, Franc¸ois Magendie, and Claude Bernard favored the view that diseases, including fevers, were intrinsic. These three giants in their field suggested and demonstrated, against forceful opposition, that (a) living organisms obey the laws of physics and chemistry, (b) disease is not a distinct entity but rather an alteration of physiology, and (c) human and animal life revolves around a milieu interieur (internal environment) that provides protection against environmental variation (13, 91, 116). By defeating vitalism, focusing on the mechanisms underlying health and disease, separating higher organisms from their environment, and raising the scientific standards of biology and medicine after a 50-year battle against the talented clinical pathologists, who had themselves established modern pathology and clinical medicine against a long-standing tradition, these three founders of modern experimental medicine made it more difficult for the germ theory to emerge.

Men of genius, albeit with a more narrow focus, such as John Snow, Ignaz Semmelweis, and Jean-Antoine Villemin, understandably failed to convince the world that fevers were contagious, despite their superb discoveries and heroic attitudes in the face of public hostility. Indeed, they failed to identify the microorganisms first seen by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in the late seventeenth century as agents of contagion. The successful fight of the great physiologists against the proponents of vital forces and vital disease entities was not without collateral damage: Diseases could hardly be seen as extrinsic, at least not until proven beyond reasonable doubt.

1868–1881: The Germ Theory of Diseases

Pasteur, who firmly established causal relationships between microbes, contagion, infection, and disease, provided a definitive solution to the problem of childhood fever. After the loss of the third of his five children to fever, Pasteur was asked in 1865 to travel to Alès to investigate the reasons for the decimation of silkworm populations (46, 165). While pursuing his PhD, Pasteur had earlier discovered the principle of chemical chirality, and he had later shown that microbial growth was responsible for fermentation and that living matter was not generated spontaneously. He established the germ theory of diseases in 1867–1868 with the discovery that two diseases of silkworms, pébrine and flacherie, were contagious and infectious (121).

These and subsequent discoveries of animal and human pathogens met with violent opposition, particularly from veterinary surgeons and physicians. Most of Pasteur’s opponents probably held out until Robert Koch’s discovery of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in 1882, when the evidence finally became irrefutable (46, 82). This then threw the spotlight on interindividual variability: Why did only some children die of fever? Infection was widely believed to be synonymous with disease, which was itself often synonymous with death. Pasteur’s aphorism “one disease, one microbe, one vaccine” reminds us of this causal relationship, which was perhaps expressed even more rigorously by Koch in his 1882 postulates, including the notion that the pathogen should be found in patients and not in healthy individuals. For European microbiologists at the time, microbes literally caused infectious diseases: They were the pathogens. They were thought to be both necessary and sufficient for the development of disease. However, with hindsight, it is interesting to note that Pasteur seems to have neglected his own previous observation that flacherie is also hereditary, in the sense that predisposition, rather than the infectious agent itself, is transmitted from parents to offspring. His chapter on flacherie, published in 1870, is actually entitled “Hereditary Flacherie.” As Dubos (49, 50) noted, Pasteur might then have decided to take a different route.

There were also other observations that did not entirely fit into the newly established paradigm based on this radical view of the germ theory of diseases. For example, the observation that not all sick children died from infection suggested that other factors, possibly relating to the nature of the host, were at play. Similarly, Max von Pettenkofer, a strong opponent of the contagion theory, survived after drinking a solution of Vibrio cholerae provided by Koch himself. Nevertheless, the germ theory of diseases was victorious in the face of much skepticism, thereby establishing what remains the greatest paradigm shift in medicine (46, 85, 101).

1882–1909: The Immunological Theory of Infectious Diseases

The first explanation for interindividual clinical variability in the course of infection followed naturally from another groundbreaking discovery by Pasteur between 1880 and 1882: the prevention of infectious diseases and the foundations of immunology, with the use of attenuated microbes to vaccinate against fowl cholera and sheep anthrax (119). Pasteur generalized the term vaccination as a tribute to Benjamin Jesty and Edward Jenner. The sheep anthrax experiment, carried out at Pouilly-le-Fort in 1881, can be seen as the birth of immunology, which would then relentlessly investigate the cellular and molecular basis of the diversity, specificity, and memory of immune responses (150). The subsequent success of vaccination against human rabies was a triumph that was acclaimed worldwide.

These observations probably gradually and implicitly led to the notion that related, less virulent microbes or smaller amounts of the same microbes had previously immunized sick individuals who survived infection with a microbe virulent enough to kill other individuals. This powerful idea forms the basis of the immunological theory of infectious diseases. We now know that this acquired immunity requires the cells and molecules of adaptive immunity, a lymphoid system with B cell and T cell arms. This system has both genetic and epigenetic components and was so crucial to vertebrates that, by convergent evolution, it emerged twice in the development of this group of animals (17, 74). The limited interindividual variability in the course of infection documented by this time could therefore be explained by a powerful emerging theory. After Pasteur’s initial hypotheses to account for immunity, two competing breakthroughs occurred: Eli Metchnikoff’s discovery of macrophage-mediated phagocytosis, and Paul Ehrlich’s discovery of antigen-specific antibody responses (150). Unsurprisingly, the antibody response became the dominant paradigm, because it paved the way for the study of specificity, diversity, and memory. The phagocyte theory was of less intellectual relevance in the immunology stemming from the first vaccination experiments (158). Moreover, two great practical breakthroughs—Fernand Widal’s discovery of serology-based diagnosis and Charles Richet’s and Emil von Behring’s discovery of serotherapy— preceded and accompanied the antibody theory (150).

The extraordinary therapeutic successes of both vaccination and serotherapy naturally provided support for the immunological theory of infectious diseases. However, Widal’s work on serodiagnosis, Richet’s work on anaphylaxis, and Clemens von Pirquet’s work on allergies soon suggested that a much larger proportion of individuals than initially thought apparently remained asymptomatic despite infection with numerous microbes. Moreover, further surprises were in store, with the realization that interindividual variability was even greater than anyone had previously imagined. The immunological theory could account for interindividual variability in the course of reactivation or secondary infections, but it had less power to explain the high degree of interindividual variability in the course of primary infections.

1910–1919: Latent and Inapparent Infections

By the turn of the twentieth century, it had become increasingly clear that most individuals infected by the greatest killers of humankind, such as M. tuberculosis, pneumococcus, and other microbes, remained completely healthy. The results of serology and hypersensitivity studies provided the first hint of this problem, but the issue was brought into sharp focus by the discovery of silent, latent infections in which dormant, nonreplicating living microbes are found in the tissues of healthy individuals. Von Pirquet’s discovery that a large proportion of individuals displayed a subcutaneous reaction to tuberculin was followed by Charles Mantoux’s observation of delayed-type hypersensitivity to intradermal tuberculin in countless infected but healthy individuals.

This problem could, however, be addressed by the immunological theory, as microbial latency and specific immunity may be seen as twin principles. One could surmise that individuals who had survived previous infection or had stronger immunity (or both) were better able to keep microbes in a dormant state. A much more difficult problem was posed by Charles Nicolle’s (111, 112) discovery of inapparent infections between 1910 and 1920. This discovery arose from his understanding of the mode of transmission of typhus, which led him to realize that the disease could be transmitted from healthy carriers and that animals and humans harboring replicating microbes in their bloodstream or tissues after primary infection could be completely asymptomatic. In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, he noted, “This new concept of inapparent infections that I introduced to pathology is, without a doubt, the most important of the discoveries that I was able to make” (110).

The specific observation that primary infections, whether acute or chronic, could be microbiologically active yet clinically asymptomatic was difficult to reconcile with existing knowledge and the two pillars on which it reposed: the germ and immunological theories of infectious diseases. The immunological theory could not easily account for such heterogeneity other than by speculation that related microbes could vaccinate some children against infectious agents. Protective immunity conferred by cross-reactivity can be seen as a radical view of the immunological theory. Likewise, a radical view of the germ theory—which we also refer to as the microbiological theory and which is based on the rapid division and evolution of microbes—attributes clinical variability to microbial variability (not necessarily qualitative, as merely quantitative differences may be at work). Yet, from the 1920s onward, the position of microbes as the sole explanation for infectious disease was challenged, and these organisms were demoted to being necessary but not sufficient for the development of infectious diseases, especially during primary infection—the principal problem faced by humans throughout their history. Fevers killed mostly children, with far fewer deaths among the elderly. Over the course of the next century, it gradually became clear that most plants, animals, and humans infected with most microbes, whether viruses, bacteria, fungi, or parasites, continue to thrive. The burden of infectious diseases, the greatest killer of mankind, has been huge, but has turned out to be due mostly to the almost infinite number of different microbes rather than to their intrinsic virulence or pathogenicity, as each microbe kills only a small proportion of the individuals it infects, with only a few exceptions (24).

1920–1949: Toward a Germline Genetic Theory of Infectious Diseases

Human geneticists in the United Kingdom proposed a genetic solution to the problem of asymptomatic infection. Pearson (123) and other population geneticists, together with Garrod (123) and other clinical geneticists, proposed that the germline genetic background of the host determines susceptibility or resistance to any given microbe. For once, population and clinical geneticists were in agreement, reinforcing the point from two complementary angles. The clinical evidence was anecdotal but thought provoking, whereas the epidemiological evidence was perhaps more subtle but well thought out, given the design of genetic epidemiological studies at the time. These geneticists did not clearly distinguish between primary and secondary infection, but they did clearly point out the responsibility of the genetic makeup of the host for determining predisposition or susceptibility to infectious diseases. These geneticists also perceived the difficulty of reconciling these views with immunological theories. Above, we quoted Garrod (63) as emphasizing how difficult it is “to distinguish between immunity which is inborn and that which has been acquired” (see also 12). Concomitantly, Theobald Smith, the first great American physician-scientist, noted that the existence of survivors in the course of epidemics “was due in part to immunological factors overlapping from other diseases, in part to genetic individual differences” (152) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The respective contributions of host and microbe genetics to the clinical outcome of infectious diseases. An individual with a strong genetic vulnerability (e.g., owing to a single-gene variant) may develop clinical disease following infection with a weakly virulent microbe, whereas an individual with a low level of genetic vulnerability may develop clinical disease only if infected with a highly virulent microbe. The infection process itself is genetically controlled, with resistant and susceptible individuals.

Some of the genetic epidemiological data obtained were strong, including, for example, those generated by the classic twin studies in tuberculosis (133). In addition, other researchers approached the problem from a completely different angle, developing animal models—including inbred mice, in particular—that yielded results leading to a similar conclusion, as some strains were vulnerable to the infections tested, whereas others were not (19, 41, 130, 153, 167, 169). Plant biologists and geneticists also noted early in the twentieth century that resistance or susceptibility to infection was genetically determined. Altogether, a powerful set of data comprising both experimental infections in plants and animals and natural infections in humans suggested that genetic makeup greatly influences predisposition or resistance to infectious diseases.

The stage was set for major progress in the late 1930s, building on multiple independent lines of thought and investigation. However, the advent of antibiotics and sulfamides in the 1930s and 1940s decreased interest in the question, why worry about the pathogenesis of childhood infectious diseases when these conditions could now be treated? In a way, these medicines killed not only microbes but also the question of clinical interindividual variability in the course of primary infection in childhood. The immunological theory of diseases could, in any case, account for some degree of interindividual heterogeneity, at least in adults and the elderly; childhood infections were left unexplained. Vaccines could prevent and antibiotics could treat childhood infections. Moreover, as discussed in detail below, the advent of antibiotics led to what is, perhaps ironically, the most helpful ascertainment bias in the history of human genetics, leading geneticists to focus their attention on rare children with multiple, recurrent, and opportunistic infections.

1950–1995: Divergent Genetic Theories of Infectious Diseases

The field of human genetics of infectious diseases entered the modern molecular and cellular era in the early 1950s. Progress began simultaneously in two different domains, heading in different directions, led by two different groups—population and clinical geneticists (3). The population genetics of infectious diseases paradoxically took off with Anthony Allison’s study of Plasmodium falciparum malaria, which he considered from the perspective of the impact of infectious diseases on human populations: In 1954, Allison showed that this type of malaria had selected for sickle cell trait carriers, providing what was arguably one of the first pieces of molecular evidence that natural selection operates in humans (6, 8). J.B.S. Haldane is sometimes presented as being the first to speculate about a possible connection between another erythrocyte disorder (thalassemia) and malaria, although others may also have made this suggestion. In any case, human genetic variation in hemoglobin (Hb) was not seen as the “cause” of malaria by any of these investigators. Instead, these studies emphasized that infectious diseases were a major force driving natural selection in humans. The intellectual roots of the field of population genetics of infectious diseases are sometimes erroneously thought to date from this period. In fact, as discussed above, the key ideas in the field are much older.

In the early 1950s, the field of human genetics of infectious diseases started off in a different direction, with the first description of primary immunodeficiencies (PIDs) by clinical geneticists. PIDs were then defined as rare, Mendelian, fully penetrant, early-onset diseases with multiple, recurrent, and opportunistic infections and overt (or at least detectable) immunological abnormalities (29, 31). The clinical phenotype that really matters and that, with the benefit of hindsight, might have been given precedence—the mere occurrence of a life-threatening infection, regardless of any subsequent infection after antibiotic-driven recovery or any detectable immunological abnormality (agammaglobulinemia, neutropenia, etc.)—was not considered by itself.

In hindsight, this narrow focus of studies on PIDs based on recurrent infection detectable only after the use of antibiotics in human populations inevitably led to a narrow definition of immunodeficient individuals (whether the deficiency was inherited or acquired) and can be viewed as an ascertainment bias. Although fruitful, this seminal misconception explains the all-too-common and ultimately erroneous oxymoron used in medical record notation of “lethal or life-threatening infection in an immunocompetent individual.” Despite this initial limitation, the field of PID research has been extraordinarily successful, with the development of immunoglobulin G (IgG) substitution, bone marrow transplantation, and gene therapy and with some of the first successes in enzyme replacement and cytokine therapy. By contrast, the field of population genetics of infectious diseases has fared less well. In any case, there was little or no communication between these two fields for approximately 50 years, until the mid-1990s, when certain observations bridged the divide between them.

1996–2012: A Unified Genetic Theory of Infectious Diseases

Until the mid-1990s, the dominant paradigm in the field of population genetics was that infectious diseases were “associated with” multiple common variants, as best illustrated by the sickle cell trait conferring resistance to severe malaria (multiple genes, one disease). Conversely, the field of clinical genetics was dominated by the idea that rare Mendelian traits confer predisposition to multiple, recurrent infections (one gene, multiple infections). The two fields ignored each other until single-gene defects in individuals and major gene effects in populations were shown to operate (one gene, one disease) (28). The first three PIDs conferring predisposition to a single infectious agent to be described were epidermodysplasia verruciformis (a predisposition to oncogenic human papillomavirus infection), membrane attack complement defects (a predisposition to Neisseria), and X-linked lymphoproliferative disease (a predisposition to Epstein-Barr virus) (31, 117, 126).

From the 1970s onward, these studies paved the way for the discovery, in the 1990s and beyond, of mutations underlying various other infections, including mycobacterial disease, pneumococcal disease, chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis, and herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE) (79, 109). Interestingly, novel population-based studies also concomitantly diverged from the old polygenic model with the discovery of major genes underlying infectious diseases common in adults, such as leishmaniasis, schistosomiasis, and leprosy, initially in segregation studies and then in genome-wide linkage analyses (3, 99, 107). These major genes were shown to have a greater impact on younger than on older adults, consistent with the general hypothesis that germline influence declines with increasing age, whereas somatic variability increasingly accounts for clinical variability with age (5). The impact of germline variability is probably stronger in children and young adults. In any case, the observation of single genes or loci underlying infections in otherwise healthy individuals or populations brought the fields of population and clinical genetics of infectious diseases together. Moreover, Mendelian resistance to infectious agents was also detected at the population level, first in the 1970s, with the Duffy antigen receptor for chemokines (DARC) and Plasmodium vivax malaria (126), and then again in the mid-1990s, with C-C chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) and human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) (45, 93, 141).

The coming together of population and clinical genetics of infectious diseases has been fruitful. In particular, it led to the hypothesis that life-threatening childhood infections are due to single-gene inborn errors of immunity in the course of primary infections. In this model (Figure 5), symptomatic reactivation and secondary infections in young adults may result from the impact of a major locus, whereas in older adults the cause may be more polygenic. Accordingly, the somatic component of disease is thought to play a more important role in disease determinism in adults. This plausible model gives meaning to a newly unified theory of infections (5). It is also consistent with all the available data, whether from population genetics or clinical genetics, and with key immunological and evolutionary concepts.

Figure 5.

A proposed age-dependent genetic architecture of infectious diseases. In this model, single-gene human variants make a major contribution to the determinism of life-threatening infectious diseases of childhood in the course of primary infection. Symptomatic reactivation and secondary infections in young adults may result from the impact of a major locus, whereas in older adults they are less influenced by human germline genetic variations (with a more complex and perhaps polygenic contribution) and probably also involve somatic factors. There is also an age-independent impact of human genetic variation on the initial step of resistance or susceptibility to the infectious process itself (e.g., DARC and Plasmodium vivax). Adapted from Reference 5.

SELECTED ILLUSTRATIONS OF MAJOR ADVANCES IN THE HUMAN GENETICS OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Here we review the progress of the field from the 1950s onward in more detail below, first in population genetics and then in clinical genetics. We arbitrarily focus on eight key diseases, studies of which have spanned the past 60 years. Below, we discuss Plasmodium falciparum malaria, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA), and herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE). In the Supplemental Appendix (follow the Supplemental Material link from the Annual Reviews home page at http://www.annualreviews.org), we discuss Plasmodium vivax infection, human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) infection, X-linked lymphoproliferative disease (XLP), and Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial diseases (MSMD).

Population Genetics of Infectious Diseases

1950s onward: Plasmodium falciparum malaria

Resistance to malaria provided the first and probably the most remarkable example of the role of common human variants in infectious diseases, with the discovery in the early 1950s of the protective effect conferred by the sickle cell trait against severe forms of P. falciparum malaria in African populations (6, 7). The sickle cell mutation (HbS) in the Hbβ-encoding gene (HBB) has a higher frequency, owing to natural selection, in regions in which P. falciparum is endemic (8, 43). Despite the death of most homozygous HbSS children with sickle cell disease, the HbS allele has reached high frequencies in African regions (up to 30%), where heterozygosity (HbAS) confers enhanced resistance to the life-threatening forms of P. falciparum malaria (8, 105).

The HbS trait may be considered the first major gene identified in a common infectious disease, based both on its frequency in some African populations and on its estimated effect on severe malaria. A major gene effect differs from a Mendelian effect in displaying lower penetrance (i.e., an incomplete effect) owing to a greater influence of both the environment and other genes in genetically predisposed individuals (2). However, such effects may still be considerable at the individual level, and a recent large meta-analysis estimated the odds ratio of developing severe malaria for HbAS heterozygotes at approximately 0.09 (95% confidence interval of 0.06–0.12) with respect to HbAA homozygotes (i.e., a risk approximately an order of magnitude lower) (159). The HbS variant also appeared to be the strongest genetic determinant of susceptibility/resistance to severe malaria in two recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) (77, 161). Another Hb variant, HbC, also enhances resistance to P. falciparum malaria, this effect being strongest in HbCC homozygotes (who have a relatively mild form of hemolytic anemia), with an estimated odds ratio of 0.27 (95% confidence interval of 0.11–0.63) in a large meta-analysis (159). This recessive resistance may account for the specific spread of the HbC variant in West Africa and the smaller number of mutation events than has been reported for HbS (87, 108).

These effects of HbS and HbC have provided fascinating insights into population genetics and evolutionary biology, offering molecular proof that natural selection operates in humans and that infection is one of the main drivers of this selection. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the protection conferred by these alleles remain unclear (171). Various non-mutually-exclusive explanations have been proposed (22), including lower levels of parasite growth in erythrocytes (53, 122), more efficient parasite-infected erythrocyte removal by phagocytes (10, 140), impairment of the cytoadhesion to endothelial cells of infected erythrocytes through the abnormal display of P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) (34, 52), accelerated development of acquired immunity to the parasite (156, 172), and translocation of sickle cell erythrocyte micro-RNAs into P. falciparum, inhibiting parasite growth (89). Finally, although HbS, HbC, and other red blood cell variants protecting against severe malaria (e.g., α-thalassemia) have been positively selected by malaria in various geographic regions worldwide (159), most people living in regions of endemic malaria do not carry any of these variants. Nevertheless, only a very small fraction of infected subjects (mostly children without erythrocyte disorders) are susceptible to severe malaria, suggesting that the human genes and variants that actually determine this life-threatening infectious disease remain to be discovered (5).

Late 2000s: Hepatitis C virus infection

From the 1950s onward, candidate-gene association studies were carried out but were not very successful in infectious diseases. Association studies following genome-wide linkage analyses were more productive, as demonstrated by the discovery of major genes underlying several steps in the pathogenesis of leprosy (4, 106). A recent GWAS on leprosy (175, 176) also identified some interesting new signals in Chinese populations that need to be followed up. However, the most remarkable achievement of GWAS, in infectious diseases and perhaps beyond, was the identification in the late 2000s of IL28B variants strongly associated with the clearance of HCV. The IL28B gene encodes the cytokine interleukin 28B (IL-28B), also known as interferon λ3 (IFN-λ3), a member of the type III IFN family (IFN-λ), which also includes IL-29 (IFN-λ1) and IL-28A (IFN-λ2) (61, 83, 148). In 2009, a GWAS on subjects of European and African American ancestry (65), along with two subsequent GWAS in Australian/European (155) and Japanese (157) populations, identified a cluster of IL28B single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (including rs12979860 in particular) strongly associated with a sustained virological response to IFN-α and ribavirin treatment in patients infected with HCV. The same variants were subsequently found to be associated with spontaneous HCV clearance (136, 160). The overall effect of these variants is strong at the population level, as the homozygous genotype for the favorable allele (i.e., associated with HCV clearance) increases the likelihood of clearance by a factor of two to three and is present at high frequency in most populations. The beneficial allele is almost fixed in eastern Asia (>90%) but has an intermediate frequency in Europe (~60–70%) and is the minor allele in Africa (~20–40%) (160). Many subsequent studies have confirmed this association in various populations and with all HCV genotypes (69) in different countries, including Egypt, which has the highest rate of HCV infection in the world (86, 124).

The molecular mechanisms underlying this association also remain elusive. IFN-λ inhibits viral replication in vitro in hepatocyte cell lines (98, 118, 138). Studies of the relationships between IL28B variants and serum IFN-λ concentration or IL28B expression in peripheral mononuclear blood cells or in the liver have provided conflicting and inconclusive results (11, 35, 69). Studies of intrahepatic IFN-stimulated gene (ISG) expression have yielded intriguing results. No relationship has been found between intrahepatic ISG expression and IL28B genotype in uninfected individuals (147), but the favorable IL28B genotype was found to be associated with low-level ISG expression in two studies focusing on subjects with chronic HCV infection (75, 163). Very interestingly, two recent studies provided a first important clue in deciphering the functional basis of this association by identifying a new dinucleotide variant, ss469415590 (TT versus ΔG), very close to IL28B (15, 132). The ss469415590 variant is in strong linkage disequilibrium with rs12979860, and the ΔG allele is superior to the rs12979860 T allele in predicting poorer response to HCV treatment. In addition, ss469415590 ΔG is a frameshift variant that created a novel gene denoted as IFNL4, encoding the IFN-λ4 protein (132). Although the discovery of ss469415590 may be a major step in the identification of the causal variant, the mechanisms by which IFN-λ4 may impair HCV clearance remain to be deciphered.

The place of IL28B genotyping in personalized treatment regimens is also a matter of debate (35). In patients who have never been treated, IL28B status may identify individuals with a high probability of achieving an early sustained virological response, in whom the duration of treatment can probably be markedly reduced. In previously treated patients, the impact of IL28B genotype is more limited and may be further decreased by the introduction of efficient new drugs such as protease inhibitors, the response to which may be independent of IL28B variant. The efficacy and safety of IFN-λ for treating HCV infection are also currently being investigated (35, 81). These discoveries relating to IL28B validate the general concept of the effect of major genes in immunity to infection. However, they also illustrate the difficulties involved in functionally dissecting the role of these variants even when there is a strong effect and the gene has plausible connections with the phenotype of interest.

Clinical Genetics of Infectious Diseases

1950s onward: X-linked agammaglobulinemia

XLA was first described in 1952 and, as such, is arguably the first PID to have been described. Ogden Bruton (20, 21) reported a boy who had suffered from 14 episodes of invasive pneumococcal disease and who lacked serum gamma globulins; the patient’s condition was improved by treatment with gamma globulins. The X-linked recessive inheritance with complete penetrance of this condition was not documented clearly until a few years later, and even more time elapsed before the description of the first autosomal recessive forms of agammaglobulinemia (ARA). In the early 1970s, patients with XLA were also shown to have very few or no circulating B cells (42, 66, 131, 149). It took 40 years to decipher the genetic etiology of XLA. In 1993, mutations were discovered in the gene encoding a newly identified cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase, which was named Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) (162, 168). BTK is specific to the hematopoietic lineage and is expressed throughout B cell differentiation (47). It is also expressed in platelets and phagocytes but not in other leukocytes (151). However, the clinical impact of BTK deficiency appears to be limited to B cells. Patients with XLA (39, 55) and those with ARA exhibit neutropenia owing to B cell-specific defects (96). BTK is activated following the activation of pre-B cell receptors or B cell receptors (BCRs) (67, 145). Activated BTK and phospholipase Cγ2 (PLCγ2) then bind to the scaffold protein BLNK, allowing BTK to phosphorylate PLCγ2 (137), leading to the generation of diacylglycerol and inositol trisphosphate (IP3). IP3, in turn, increases calcium levels in the cytosol, driving cell proliferation. More than 600 different mutations of the BTK gene have been identified (37, 164), most of which result in an absence of detectable BTK (in monocytes and platelets) (59, 60, 64). Mutations that do not affect the stability of the protein are associated with a milder immunological and clinical phenotype (18, 95, 129). Mutations of BTK account for 85% of agammaglobulinemia cases (40).

Other patients with ARA carry mutations in genes encoding components of the pre-BCR and BCR, including the µ heavy chain (57, 96, 166, 174), the surrogate light-chain protein λ5 (103), the signal transduction molecules Igα and Igβ (48, 57, 102), and BLNK (104, 166). More recently, a child with ARA was found to be homozygous for a mutation of the PI3 kinase p85α–encoding gene (38). In patients with mutations affecting BTK, the µ heavy chain, λ5, Igα, Igβ, or BLNK, B cell development in the bone marrow is blocked at the pro–B cell to pre–B cell transition, the stage at which the pre-BCR is first expressed. However, BTK gene mutations cause a leaky defect in B cell differentiation. Most patients with XLA have small numbers of pre-B cells in the bone marrow and immature B cells in the bloodstream (36, 113, 114), which decrease further with age (115). Mutations in the other genes cause a more severe blockade of B cell development. Null mutations of the genes encoding the µ heavy chain, Igα, and Igβ result in a complete absence of circulating B cells. Children with mutations in the genes encoding λ5 or BLNK have a very small number of B cells. By contrast, mice with BTK, λ5, or BLNK defects have normal numbers of circulating B cells, illustrating the differences in B cell differentiation between humans and mice. The global immunological phenotype of a patient mutated in PI3 kinase p85α differs to an even greater extent from that of the corresponding mouse (38).

Patients with XLA or ARA are prone to peripheral and systemic pyogenic bacterial infections, and this is clearly the principal infectious phenotype of these patients. They are also prone to enteroviral infections (39, 44, 100, 134, 173), mycoplasma and ureaplasma infections (58, 139), and Giardia infections (94). Significant complications and early death are still sometimes reported (173), but many patients now survive into adulthood, thanks to IgG substitution (76). Indeed, since Bruton’s work, IgG substitution has proven highly effective for preventing infectious diseases in these patients. Inherited agammaglobulinemias are “experiments of nature” that identified the microbial infections for which antibody immunity was critical well before any such conclusions could be drawn from studies in the mouse model. Some of the infections (enterovirus, mycoplasma, Giardia) seen in these patients remain thought provoking. The spectrum of infections in patients with XLA or ARA is broad but relatively specific, as in most of the classical PIDs described in the 1950s and 1960s.

Late 2000s: Herpes simplex encephalitis

HSE is perhaps the most striking example of an isolated and severe childhood infection eventually shown to result from single-gene inborn errors of immunity (1). In this terrible disease, the most common sporadic viral encephalitis in Western countries, the virus is restricted to the central nervous system (CNS). It is absent from the bloodstream and does not spread to other organs. HSV-1 is neurotropic in terms of both the route it follows and its destination: It reaches the CNS via cranial nerves. Patients with the most severe myeloid and lymphoid PIDs, including children with no T cells, display no particular susceptibility to HSE. The disease is sporadic in the vast majority of cases, with only four multiplex kindreds reported in 60 years. There is, however, a high frequency of parental consanguinity (12% in the French survey), suggesting that HSE may be due to single-gene inborn errors of immunity displaying incomplete clinical penetrance (1).

The first genetic etiology of HSE was identified as autosomal recessive UNC-93B deficiency, resulting in an impairment of cellular responses to the four intracellular Toll-like receptors (TLRs), including TLR3 (32). Involvement of the TLR3 pathway was then suspected, because IRAK-4- and MyD88-deficient patients, whose cells do not respond to TLR7–9 agonists, are not prone to HSE (30, 84, 127, 128, 170). TLR3 was formally implicated in the disease when autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive TLR3 deficiencies were discovered in other patients with HSE (68, 177). The subsequent identification of children with autosomal recessive or autosomal dominant TRIF deficiency confirmed the role of the TLR3-TRIF circuit and further suggested that childhood HSE might result from a collection of highly diverse but immunologically related single-gene lesions (143) (Figure 6). HSE-causing heterozygous mutations of TRAF3 further highlighted the potential role of subtle mutations in pleiotropic genes in narrow clinical phenotypes. In autosomal dominant TRAF3 deficiency, the mutation is dominant-negative and impaired TLR3 responses account for HSE, whereas the other cellular phenotypes, such as impaired responses to members of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily, are clinically silent (125). There is a broad immunological phenotype but a narrow infectious phenotype, probably because the thresholds for clinical consequences differ between cellular phenotypes. By contrast, in autosomal dominant TBK1 deficiency—a more recently defined etiology of HSE—there is a narrow cellular phenotype, apparently restricted to the TLR3 pathway, although TBK1, like TRAF3, is involved in multiple signaling pathways (70). This is consistent with the narrow infectious phenotype. Patients with NEMO mutations are broadly susceptible to viral infections, including HSE, reflecting the impairment of antiviral IFN production in response to the stimulation of multiple receptors, including TLR3, in their cells (9). The target genes downstream from TLR3 involved in HSE were identified as antiviral IFN-encoding genes in 2003, when patients with complete STAT1 deficiency were found to be prone to multiple viral diseases, including HSE (51, 142, 144).

Figure 6.

Inborn errors of TLR3TFN-α/β-mediated immunity in childhood herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE): schematic representation of the production of and response to IFN-α/β and IFN-λ in herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) immunity. HSV-1 produces viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) during its replication. TLR3 is a transmembrane receptor of dsRNA in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and endosome in most cells. In central nervous system (CNS) cells, the recognition of dsRNA by TLR3 induces activation of the IRF3 and NF-κB pathways via TRIF, leading to the production of IFN-α/β and/or IFN-λ. TLR3, UNC-93B, TRIF, TRAF3, TBK1, and NEMO deficiencies are associated with impaired IFN-α/β and/or IFN-λ production, particularly during HSV-1 infection. The binding of IFN-α/β or IFN-λ to its receptor induces the phosphorylation of JAK1 and TYK2, activating the signal transduction proteins STAT1, STAT2, and IRF9. This complex is translocated, as a heterotrimer, to the nucleus, where it acts as a transcriptional activator, binding to specific DNA response elements in the promoter region of IFN-inducible genes. STAT1 deficiencies are associated with impaired IFN-α, -β, and -λ responses. Proteins for which genetic mutations have been identified and associated with susceptibility to isolated HSE are shown in blue. Proteins for which genetic mutations have been identified and associated with susceptibility to mycobacterial, bacterial, and viral diseases (including HSE) are shown in green. Proteins for which genetic mutations have been identified but not directly associated with susceptibility to HSE are shown in red.

All the genetic etiologies of isolated HSE display complete penetrance at the cellular level (in fibroblasts) but incomplete clinical penetrance, accounting for the sporadic nature of HSE. Interestingly, these defects also predispose subjects to childhood HSE in the course of primary infection, but they do not seem to impair immunity to latent HSV-1 infection in the CNS or elsewhere. The molecular dissection of HSE also led to its cellular dissection. The TLR3 pathway was recently shown to be largely redundant for poly(I:C) responses in keratinocytes and leukocytes, whereas it is essential in induced pluripotent stem cell–derived CNS cells, including neural stem cells, astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes (88). However, anti-HSV1 immunity was shown to be critically dependent on the TLR3-dependent production of IFN-α/β in neurons and oligo-dendrocytes only. These findings strongly suggest that HSE results from a CNS-intrinsic defect of antiviral immunity. It probably results from a collection of single-gene inborn errors of TLR3 intrinsic immunity operating in CNS-resident cells, including neurons and oligodendrocytes in particular. Overall, the genetic dissection of HSE has shed new light on host defenses, revealing that the TLR3 pathway is responsible for ensuring CNS-intrinsic protective immunity against HSV-1 during primary but not latent infection. Future studies will search for new genetic etiologies of HSE and determine whether HSE is a valid general model for the genetic architecture of isolated life-threatening childhood infectious diseases (5).

SOME PERSPECTIVES

There is currently no proven general genetic architecture of infectious diseases. According to our model (Figure 5), life-threatening primary infections of childhood often result primarily from single-gene inborn errors of immunity, whereas reactivation and secondary infections in adults result from a more complex combination of microbiological, ecological, somatic (genetic and epigenetic), and germline variation, this last type probably being more polygenic than monogenic (particularly in the elderly population). In this age-dependent model of infectious diseases, there is a continuous spectrum, from highly penetrant monogenic determinism to weakly penetrant polygenic predisposition. In turn, the genetic control of infection itself is understandably age independent, as attested to by the known Mendelian traits underlying complete resistance to three infectious agents (P. vivax, HIV, and norovirus). This model is supported by almost all the available clinical, epidemiological, and evolutionary genetic data, including, in particular, the eight illustrative examples discussed above and in the Supplemental Appendix. In what way are other models, such as the universal polygenic model (and the “common variant, common disease” hypothesis), for which a convincing paradigm could not be established, unsatisfactory (33, 71–73)?

First, the genetic basis of adult infections was often tackled, although such infections can be explained largely by the immunological theory (related infections and vaccinations, etc.) and the microbiological and ecological theories; there is no absolute need for a genetic theory in these cases. The inherited genetic components of adult reactivation and secondary infections may be very limited, to the extent that they cannot be detected owing to confounding somatic factors and genetic heterogeneity. However, adaptive immunity is also genetically controlled, so there may be some genetic effect, as neatly illustrated by the impact of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles on HIV disease progression. Moreover, major genes may operate in young adults, via rare or more common variants (Figure 5).

Second, there is the problem of the use of an approach based exclusively on population studies and testing of the role of common variants, even when enrolling children (together with adults). The vast majority of these studies have yielded weak and poorly reproducible associations. Our novel model focuses on the search for rare single-gene lesions in children with life-threatening infections, at least as a first approach. More benign infections of childhood may display a more complex inheritance pattern. Needless to say, the lesions underlying severe infections are unlikely to display full penetrance, and there may be oligogenic determinism or epistasis in some children, as humans are not single-gene organisms. Indeed, the question of penetrance is central to this model, with single-gene lesions displaying high but incomplete clinical penetrance, leading to the search for modifiers, which may or may not be genetic.

This model is now experimentally testable and has clearly received a boost from whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing. The genetic theory is not only complementary to the microbiological and immunological theories but also compatible with Dubos’s ecological theory, including the impact of dual infections, which we have not reviewed here (16, 50, 154). Indeed, as stated in our introduction, the four theories overlap; for example, the immunological theory refers to somatic processes that are controlled by the germline, the genetic theory is a germline theory of immunity, and the ecological theory involves immune responses.

If documented, a tight genetic determination of severe childhood infections would have considerable immunological implications. This genetic architecture would provide new insights into immunity to primary infections. The field of immunology has been fundamentally and primarily interested in somatic, acquired immunity to “antigens”—thought of initially as infectious agents and then as pure chemical compounds from the work of Karl Landsteiner starting in 1917 (90). Metchnikoff received little credit and courted much controversy in the mainstream immunological community largely because of his interest in both infections and phagocytes rather than specific immunity. The field of innate immunity (granulocytes and macrophages) remained in the shadow of adaptive immunity for many decades, at least until antigen presentation by macrophages and the priming of T cells by dendritic cells were established in the 1970s and 1980s. Other studies on phagocytes were typically conducted by hematologists, resulting in several gaps in immunological knowledge. For example, severe congenital neutropenia, first described in the early 1950s, was not included in classifications of inborn errors of immunity until the 1990s (31). The study of intrinsic, nonhematopoietic immunity is still not considered a branch of immunology (88).

However, studies of immunity to infection returned to the fore in the 1990s, after 60 or 70 years in which studies of immunity to chemical antigens had predominated. Studies of the role of phagocytes in the response to infection have benefited from human genetic studies (e.g., for chronic granulomatous disease and the phagocyte respiratory burst) (146). They have also benefited from the study of various experimental infections in knockout mice (by reverse genetics) (80) and the concomitant exploration of innate immune receptors for various microbes using natural mouse mutants (by forward genetics) (14, 168).

The mouse model can be used to study immunity to primary infection (or its intrinsic, innate, or adaptive components) and is highly suitable for studies of immunity to secondary infection (mostly its adaptive component) because mice can easily be experimentally inoculated. However, it is also rewarding to study primary infections in humans, because such infections occur naturally and cause most of the infectious burden. The study of reactivation or secondary infections in humans is more difficult, but human studies have the major advantage of defining immunity in natura, i.e., in a natural ecosystem governed by natural selection (25, 26, 29, 30, 135). Animal models of experimental infection suffer from the limitations inherent to such experiments, as discussed in detail elsewhere (25, 26, 29, 30, 135). Indeed, there is a much greater level of redundancy in human immunity, as illustrated by numerous experiments of nature, some of which have been reviewed here (25, 30). Overall, the genetic approach to childhood infectious diseases helps to focus immunology on immunity to primary infection in natural conditions, through the consideration of its intrinsic, innate, and adaptive branches together. Genetic dissection of the underlying single-gene lesions has powerful immunological implications, some of which have been illustrated here.

The clinical implications of this genetic model are both considerable and timely, as new, emerging, and reemerging microbes—including not only HIV and influenza viruses but also antibiotic-resistant common pathogens, such as methicillin-resistant staphylococci and multi-drug-resistant M. tuberculosis—are posing new and challenging threats to humanity. This genetic model allows rigorous molecular diagnosis and genetic counseling based on the identification of causal, morbid genetic lesions of known penetrance in a large number of families worldwide. The prognosis and more personalized treatment and follow-up can also be defined on the basis of genetic lesions. Indeed, perhaps more important, these studies pave the way for cytokine therapy in vulnerable individuals with inborn errors of the corresponding cytokine-encoding gene (or of another immunological molecule–encoding gene). Prevention or treatment with recombinant cytokines is based on the same principle as the use of insulin in diabetic patients. Such treatment is already being used, with children worldwide benefiting from treatment with IFN-γ, G-CSF, or other recombinant molecules.

The widely held notion that infectious diseases are “controlled” by conventional means (hygiene, surgery, vaccines, and antimicrobial agents), and that research in this field should simply reproduce approaches that have worked in the past and increased life expectancy from 20 to 80 years, is somewhat naive, if only because it is based entirely on the past 100 years. If we consider the past 10,000 years, greater caution would seem advisable. Yes, the success of the germ and immunological theories has been spectacular, but known diseases have remained formidable killers, and new diseases and new antibiotic-resistant strains are emerging. It is absolutely critical to develop a full understanding of the pathogenesis of infectious diseases. In the long term, such an understanding constitutes our best hope of controlling these diseases. The microbiological approach has worked beautifully: The dissection of microbial pathogenesis facilitated the development of powerful medicines, beginning with sulfamides. The immunological approach has also been highly successful: The dissection of adaptive immunity has facilitated the development of better vaccines, although vaccine research remains largely empirical. However, new microbes and drug-resistant microbes will inevitably emerge. Moreover, the failure of vaccination strategies for historically important diseases, such as malaria and tuberculosis, raises questions about whether effective vaccines for these diseases can actually be designed.

Building on the impressive strides forward being made in the development of genetic technologies, the human genetic approach provides a complementary method for investigating ways of combating infectious diseases that is critical for the development of host-directed anti-infectious agents and, perhaps, human genetics-based vaccination strategies. There may be no more surprising and beneficial fruits of Garrod’s seminal concepts of “chemical individuality” and “inborn errors” (12, 62, 63) than the patient-based dissection of the genetic determinism of infectious diseases.

Supplementary Material

SUMMARY POINTS.

The physiological revolution (Lavoisier, Magendie, Bernard) paradoxically made it more difficult to establish the germ theory of diseases (from Snow, Semmelweis, and Villemin up to Pasteur). Once established, the germ theory in turn made it difficult to digest the demonstration of latent and inapparent asymptomatic infections (von Pirquet, Nicolle). The fundamental problem in the field of infectious diseases was posed in the years 1905–1915 with the gradual discovery that most people, including most children, were infected asymptomatically with most microbes even during the course of primary infection. So how can we account for interindividual variability in the course of infection?

The immunological theory (Pasteur, Ehrlich) best accounts for interindividual variability in the course of reactivation and secondary infection. This is a somatic theory, with acquired adaptive immunity contributing to the outcome of infection. It was not originally conceived to account for interindividual variability in the course of primary infection. Phagocytosis and innate immunity (Metchnikoff) could not account for the specificity of immune responses and were not thought to be genetically determined.

The concept of inborn errors of immunity originated from both population genetics (Pearson) and clinical genetics (Garrod). Population geneticists (as well as quantitative, epidemiological, and evolutionary geneticists) and clinical geneticists (as well as Mendelian, chromosomal, and molecular geneticists) have often disagreed over the past century, but they agreed early on that infectious diseases have a strong germline genetic determinism in individuals and populations.

A number of elegant genetic studies in plant and animal models, by forward genetics in particular, have established that host genetic makeup is an essential determinant of susceptibility or resistance to infection. In the mouse model, spectacular achievements have resulted from strain comparisons and linkage studies—leading, for example, to the discovery of the Bcg (Nramp1), Cmv (Ly49h), and Lps (TLR4) loci. The study of quantitative trait loci and the development of N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) programs have extended this fruitful line of research to the host component of infectious diseases (14, 168).

At the population level, the field of human genetics of infectious diseases began with the discovery that the sickle cell trait provides significant protection against severe forms of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Many other candidate-gene association studies failed to reach such a level of significance and robustness. Genome-wide linkage studies have been more successful, with the identification of major loci for schistosomiasis and leprosy. Genome-wide association studies have been less successful so far, with the notable exception of the important discovery of the role of IFN-λ in the clearance of HCV infection, spontaneously or in response to IFN-α treatment.

There are examples of Mendelian resistance to virulent agents at the population level. Individuals lacking DARC expression on erythrocytes are resistant to Plasmodium vivax. Those lacking functional CCR5 are resistant to R5-tropic strains of HIV. Those lacking FUT2 are resistant to noroviruses. All three deficiencies are autosomal recessive.

According to their first descriptions in the 1950s, classical primary immunodeficiencies are fully penetrant Mendelian traits that confer early-onset vulnerability to multiple, recurrent, opportunistic infections owing to a detectable immunological phenotype. X-linked agammaglobulinemia is a typical example of such a disease.

From the 1970s onward, new primary immunodeficiencies were shown to confer predisposition to a single infectious agent. This is illustrated by X-linked lymphoproliferative disease and susceptibility to Epstein-Barr virus. Other examples include epidermodysplasia verruciformis (papillomaviruses) and defects of the terminal components of complement (Neisseria). The most thoroughly investigated syndrome is Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial diseases, leading to the dissection of the first genetic etiologies of childhood tuberculosis. The genetic dissection of childhood herpes simplex encephalitis provided the first example of a sporadic, common primary infectious disease owing to single-gene inborn errors of immunity with incomplete clinical penetrance.

FUTURE ISSUES.

Deciphering single-gene lesions underlying life-threatening infectious diseases of children: Currently, only a very small proportion of individual infections and infected individuals are understood in genetic terms. This process is facilitated by next-generation sequencing, but there are many infections and countless sick children, and the level of genetic heterogeneity may be very high.

Investigating the frequency of morbid alleles and their actual clinical penetrance: The respective roles of very rare (unique or familial), rare, and more common alleles in the determinism of very rare (a few patients), rare, and more common infections should be defined. A related goal is understanding the mechanisms underlying incomplete clinical penetrance (modifier genes, microbial factors, etc.).

Exploring the interactions between the human genome and microbial genomes: The fields of cellular microbiology and microbial pathogenesis should be combined with that of human genetics to improve dissection of the actual pathogenesis of infectious diseases. Some inborn errors of immunity may be specific not only to certain microbes but also to microbes expressing specific factors or to microbes infecting specific tissues and organs.

Deciphering the Mendelian basis of resistance to past and present life-threatening infectious diseases caused by highly virulent microbes upon primary infection at all ages: Current examples include Ebola virus disease, coronavirus respiratory disease (SARS), avian flu, and swine flu; past examples include plague and poliomyelitis.

Dissecting the inherited component of adult infectious diseases: This component will be difficult to disentangle from the contribution of somatic immunity, with its genetic (antigen-receptor repertoire) and epigenetic (cytokine and receptor profiles) components. This is particularly important for diseases such as tuberculosis, which are transmitted by sick adults following reactivation from latency.

Genetically investigating the relationship between the tissue specificity of numerous childhood infections and the contribution of intrinsic immunity: The role of non-hematopoietic cells has historically been neglected in immunology. Herpes simplex encephalitis is an example of a disease caused by single-gene inborn errors of intrinsic immunity in the central nervous system. There are almost certainly other examples.

Translating human genetic findings into therapeutic advances: This would allow the molecular diagnosis of patients, genetic counseling of their families, and improvements in the prediction of prognosis. It would also make it possible to develop novel treatments with recombinant molecules aiming to remedy the genetic deficiency of the immune system, and might lead to new types of vaccines or to the vaccination of targeted individuals.

Revisiting immunology based on studies of the genetic determinism of clinical disease in the course of primary infection, in children and young adults in particular: The dissection of experiments of nature provides the unique added value that the function of host defense genes is defined in natura, i.e., in the setting of a natural ecosystem governed by natural selection.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to our colleagues for the many references we were unable to cite owing to space limitations. We also thank Alexandre Alcaïs, Stéphanie Boisson-Dupuis, Aziz Bousfiha, Minji Byun, Yuval Itan, Rebeca Pérez de Diego, and Shen-Ying Zhang for critical reading, and all members of the laboratory for helpful discussions. Work in the laboratory has been supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (grant 8UL1TR000043), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grants 5R01AI088364, 5R01NS072381, 5P01AI061093, 5R01AI089970, 5R37AI095983, and 5U01AI088685), the St. Giles Foundation, the French National Agency for Research, the European Union grant HOMITB (HEALTH-F3-2008-200732), the European Research Council (grant ERC-2010-AdG-268777), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Jeffrey Modell Foundation and Talecris Biotherapeutics, the Thrasher Research Fund, the March of Dimes Foundation, Institute Mérieux, the Dana Foundation, the Gerber Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Rockefeller University, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, and Paris Descartes University.

Glossary

- Immunological (somatic) theory of infectious diseases

the proven notion that acquired immunity, which is a somatic process mediated by adaptive immunity, contributes to the clinical expression of infection

- Genetic (germline) theory of infectious diseases