Abstract

Child sexual abuse (CSA) is a critical, psychologically traumatic and sometimes life-threatening incident often associated with sequel of adverse physical, behavioral, and mental health consequences. Factors such as developmental age of the child, severity of abuse, closeness to the perpetrator, availability of medico-legal-social support network and family care, gender stereotypes in the community complicate the psychological trauma. Although the research on the effects of CSA as well as psychological intervention to reduce the victimization and promote the mental health of the child is in its infancy stage in India, the global research in the past three decades has progressed much ahead. A search was performed using MEDLINE, PubMed, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar from 1984 to 2015 and only 17 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) out of 96 potentially relevant studies were included. While nonspecific therapies covering a wide variety of outcome variables were prominent till 1999s, the trend changed to specific and focused forms of trauma-focused therapies in next one-and-half decades. Novel approaches to psychological interventions have also been witnessed. One intervention (non-RCT) study on effects on general counseling has been reported from India.

Key words: Child sexual abuse, psychological intervention, randomized controlled trials, trauma

INTRODUCTION

Children with sexual abuse undergo sequel of adverse physical, behavioral and mental health consequences which profoundly affect their overall development.[1,2,3] Depending upon the type, severity of abuse and availability of support, often such difficulties persists over years.[4] Literature on psychological treatment of children who have been sexually abused is relatively young. However, some of the recent reviews have been published in the past,[5,6] focuses on various integrated approaches along with cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). However, there is a dearth of such efficacy studies based on these therapeutic models in India. Moreover, there has been almost no such specific intervention developed keeping Indian cultural needs in mind. Thus, the aim of this paper is to review the existing reported evidence-based research in this area in last 30 years and to identify the gap exists between intervention studies worldwide and India so as to highlight the need in the Indian context.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

An electronic search of the articles was undertaken in PubMed from 1984 to March 2015, to include all studies of psychological treatments for children and their families where a child has been sexually abused. A search was performed using MEDLINE, PubMed, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar from 1984 to 2015. Key search terms used in the search were (“Child Sexual Abuse” OR “Sexual Assault of Children” OR “Child Sexual Abuse Survivors” OR “Childhood Sexual Trauma”) AND (“Psychotherapy” OR “Intervention OR “Treatment”) AND (“Randomized Controlled Trial” OR “Case Study” OR “Reviews”).

Selection of studies

The publications that focused only on psychological treatment of child sexual abuse (CSA) were included in this paper. Titles and abstracts of all potentially relevant articles were reviewed for possible inclusion. Articles were included if:

It was primarily a psychological intervention,

The interventions primarily focused on treatment of CSA,

The study was a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of CSA, assessment, or intervention with at least a no-treatment control,

It included children below the age 18 years and not with adults or couples with history of CSA, and

Such studies done in the past 30 years only (with a division of 2 times lines with 15 years of interval, from 1984 to 1999 and 2000 to 2015).

The articles reporting treatment of abuse in general or those including community or group interventions were not included the study.

Data extraction and exclusion criteria

Full texts of the identified literature were obtained. The main outcome measure of interest was improvement in the mental health indicators of children with sexual abuse (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD] symptoms, depressive symptoms, shame, guilt, fear, academic achievement, and behavioral difficulties). Where data was insufficient or not available in the published paper or by contacting authors, studies were excluded from the relevant analysis. Articles describing the study protocols and dissertations, case reports, case series or reviews describing the psychological treatment of CSA were also excluded from the analysis.

RESULTS

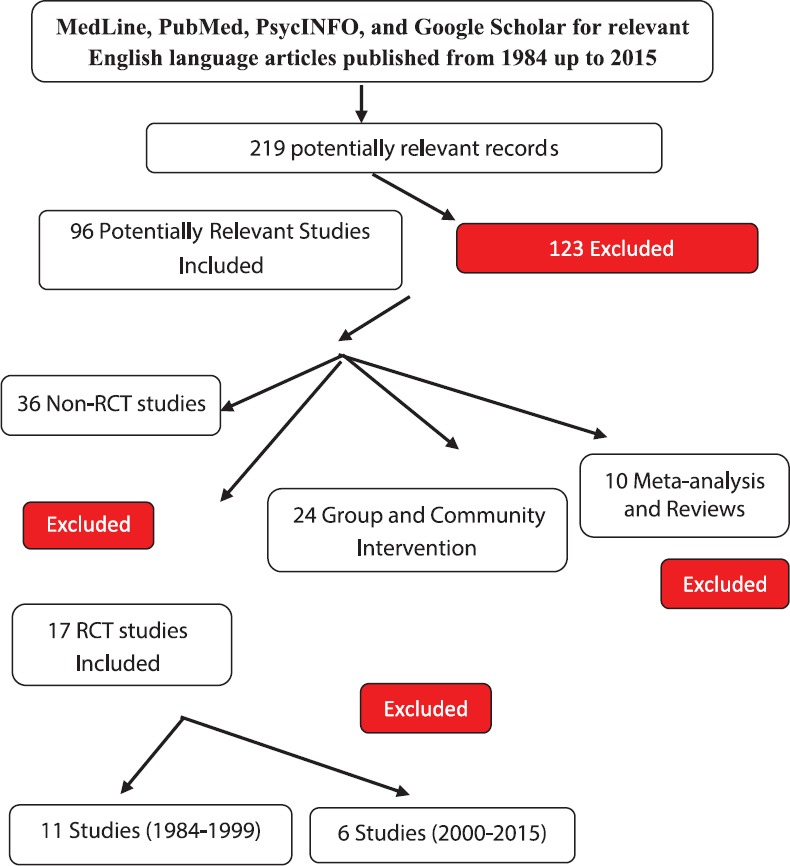

Ten out of a total of 219 identified potentially relevant records were reviews or meta-analysis. A total of 96 studies evaluating the role of psychological interventions in CSA were included in this review. The summary of the process of obtaining the studies for review and its further division are mentioned [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Comprehensive data search flowchart

FINDINGS

A total of 17 (11 studies during 1984-1999 and 6 studies during 2000-2015) studies evaluating the role of various forms of psychotherapy in CSA with rigorous RCT methodology were included. The characteristics of the studies and participants, results of the quality assessment and key findings are described in the following sections.

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Recruitment

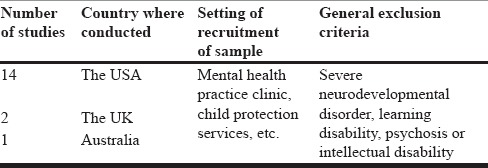

As summarized in Table 1 out of 17 studies, 14 studies are solely from the United States, one in Australia, and two in the United Kingdom. The study recruited participants from a variety of sources, mental health practitioners, child protection services, etc. Most studies included in their selection criteria children who experienced sexual abuse recently, which is verified by relevant child protection and youth justice agency. Children with severe neurodevelopmental disorder, learning disability, psychosis or intellectual disability were excluded.

Table 1.

Country specific RCT setting and exclusion

Description of studies

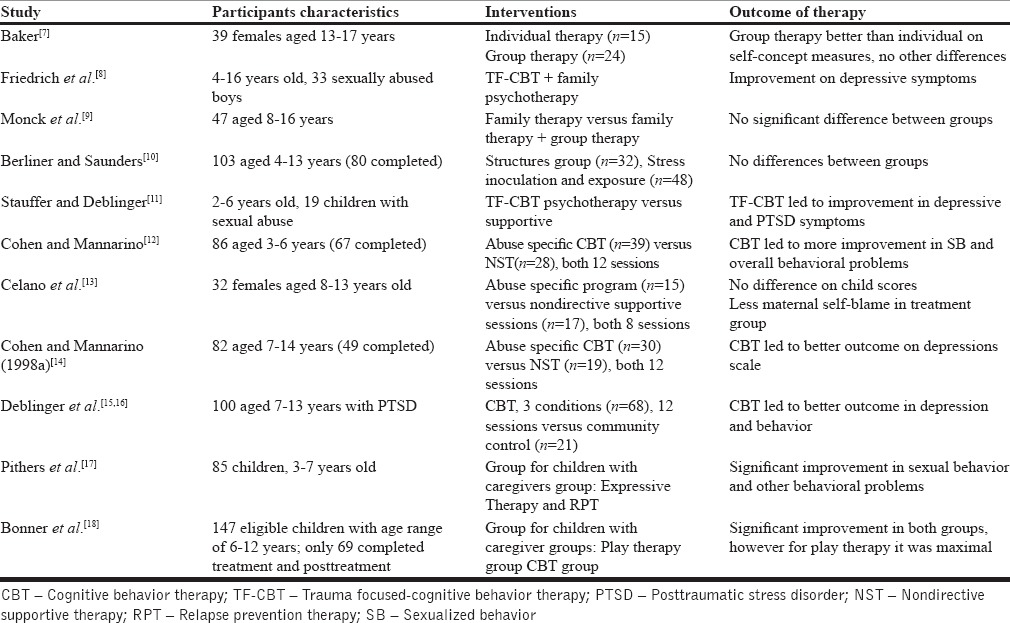

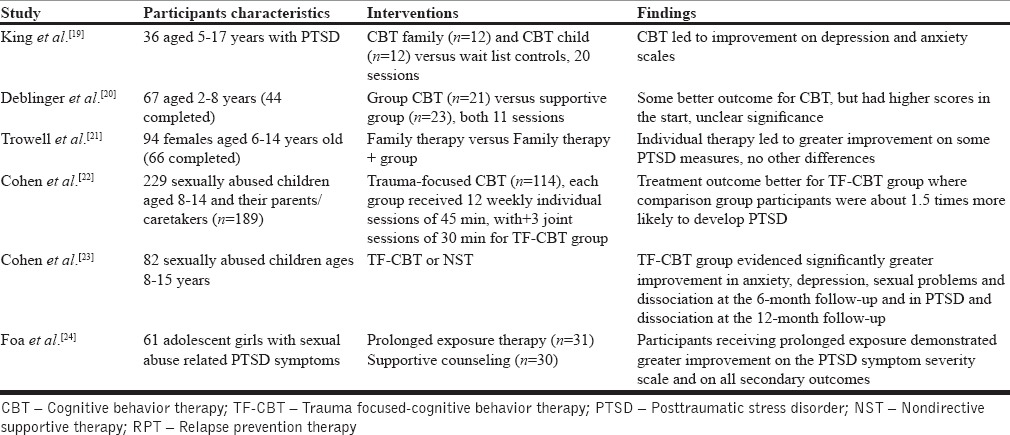

Details of the nature of child participation, type of intervention used and the outcome are elaborated in detail in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Treatment outcome studies from 1985 to 2000

Table 3.

Treatment outcome studies from 2000 to 2015

DISCUSSION

Methodological description of studies

Of the 17 studies included in the review, five described the method of randomization. Only one study[13] described masking of therapist's assessment by clinicians. One study[22] described a multisite RCT and clustered RCT.[20] The attrition rate varied from study to study. Risk of selection bias also varied across studies.

Age and gender of the participants

The review reveals that the lowest age at which intervention has been carried out is 2 years[11,20] and the age ranged from 8 to 15.[13,15,16,22,23] Only 4 studies have focused exclusively on one gender and the female, and male ratio was 3:1.[7,8,13,21] However, other 13 studies have taken participants from either gender and have not particularly distinguished between two.

Nature of intervention

Intervention type and techniques

Most of these interventions since the early 1990s adopted integrated therapeutic module where combined counseling sessions for children and parents were the key focus in symptoms reduction. Some of the major skills that most of these studies have highlighted progressed from rapport building, teaching rules about sexual behavior, identifying stimuli and context that increases risk, explaining cycle of abuse, emotional regulation skills, cognitive coping skills, relaxation, sex education, self-control skills, abuse prevention skills, graded exposure, attachment with parents and caregivers, parent and child management skills, working on self-esteem, shame, fear, sexual urges, arousal, and reconditioning. Many of these therapies also included components of stress inoculation therapy, group therapy, and family intervention.

From 2000 onward, however, trend clearly shifted toward utilizing specific CBT framework of child CBT and trauma-focused CBT to teach children new skills of managing their affective, cognitive, and behavioral responses to the traumatic events. Key components in this module were coping skills, types of touch, abuse response skills, ways to doing disclosure, deal with postabuse distress and PTSD symptoms, dealing with self-blame/stigmatization, betrayal feelings, traumatic sexualization, and powerlessness. Some of the studies have also utilized various expressive techniques along with supportive counseling techniques. The CBT therapy has been usually augmented with sessions with parents and caregivers on child behavior management skills, supporting them enough and working on building bonding and communication skills between them.

Overall, multidimensional therapy with a flexible and customization approach seemed to be useful in various studies.

Number of sessions

The average number of sessions to complete the recovery program was 11 with a variation in group or individual intervention format (e.g., individual therapy contains 11-12 sessions, while group therapy module contained 6-8 sessions). The key reason behind the variation may be attributed to the target symptoms and outcomes.

Frequency of sessions

Most of the therapy sessions were conducted once weekly for 45 min. Overall, it took 11-12 weeks to complete the entire therapeutic program depending upon the nature of therapeutic module utilized.

Therapeutic benefit

The benefit of intervention has been mostly seen in reduction in PTSD, depression, and other internalizing symptoms. Aspects of self-appraisal sexualized behavior and externalizing symptoms also show significant improvement. Less therapeutic benefit has been seen in coping skill, caregiver outcome, and social skills and competence.

Findings from nonrandomized controlled trial studies

Although non-RCT studies were not primarily within the purview of this paper, a selected number of studies were considered for inclusion to provide a trend in this regard. Among non-RCT studies, various studies were reviewed which included various case studies, case series designs, longitudinal case studies, and single case designs.

Cognitive processing therapy, for example, is emerging as an effective treatment of PTSD symptoms in children.[25,26] Cognitive behavior group therapy has also been reported to be one of the effective approaches to deal with trauma in CSA.

Psychotherapy for CSA also included various modality specific therapeutic techniques (e.g., animal-assisted therapy). Particularly groups that included therapy dogs showed significant decreases in trauma symptoms including anxiety, depression, anger, PTSD, dissociation, and sexual concerns.[27] Music therapy also shows a significant reduction in distress associated with trauma of sexual abuse.[28] The effectiveness of game-based CBT group program[29] and group therapy was also reported as effective techniques among children and adolescence.[30,31,32]

Current Indian scenario: Identifying gaps and emerging needs

Research on CSA in India is still in infancy. A majority of studies have been reports of government on prevalence rate in India. Some studies have focused on studying the prevalence and characteristics of CSA in vulnerable population such as street children. One such recent study on 189 nondelinquent boys (most of them were runaways) in an observation home at Delhi reported that 38.1% were subjected to sexual abuse with a mean age of abuse between 8 and 10 years.[33] However, no direct study on exploring the trauma or intervention techniques in children with CSA was found.

It was found that the intervention studies in the past 30 years focused on CBT, especially “Trauma focused-and abuse-focused” CBT has proven efficacy across studies. Surprisingly, no RCT is reported from Asian/SAARC region, therefore, to the authors' interest, no such literature is available on cultural adaptation of these forms of CBT in India. Moreover, among many evidence-based techniques, the impact of one of the expressive techniques, like play therapy has also not yet explored in Indian literature. In addition, integrated group and family interventions have never been tested. Further, limited outcome variables have been measured. Only one reported intervention study which is focused primarily on positive effects of general counseling[34] on symptom reduction. Thus, interventions available for use in India miss out on parents, family members, and community. Cultural adaptation of trauma and abuse-focused therapy along with integration of culturally appropriate intervention module needs to be developed.

CONCLUSION, LIMITATIONS, AND FUTURE DIRECTION

The review highlights few major implications for future researchers to focus on reducing methodological limitations. Further, the review also outlines the importance of adequate research attention in identifying the issues related to male survivors of CSA. The upcoming researches should also undertake studies on the replication and effectiveness of various novel intervention techniques such as body-oriented therapy[35] dialectical behavior therapy,[36] and emotionally focused therapy[37] which have been studied in adult's survivors of CSA. Variables having treatment implications on overall mental health and wellbeing of the children, such as therapy discontinuity, gap in treatment-seeking behavior, long-term follow-up in intervention, should also gain attention. There is an emerging need to conduct scientific research studies on CSA, which includes replicating effective trauma based intervention along with including various indigenous variations and it is systematic research implication in the Indian context.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kendall-Tackett KA, Williams LM, Finkelhor D. Impact of sexual abuse on children: A review and synthesis of recent empirical studies. Psychol Bull. 1993;113:164–80. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berlin L, Elliott D. Sexual abuse of children in the field of child maltreatment. In: Myers JEB, Berliner L, Briere J, Hendrix CT, Jenny C, Reid T, et al., editors. The APSAC Handbook on Child Maltreatment. 2nd ed. London: Sage; 2002. pp. 55–78. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Putnam FW. Ten-year research update review: Child sexual abuse. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:269–78. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tebbutt J, Swanston H, Oates RK, O'Toole BI. Five years after child sexual abuse: Persisting dysfunction and problems of prediction. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:330–9. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macdonald G, Higgins JP, Ramchandani P, Valentine JC, Bronger LP, Klein P, et al. Cognitive-behavioural interventions for children who have been sexually abused. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:1–53. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001930.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramchandani P, Jones DP. Treating psychological symptoms in sexually abused children: From research findings to service provision. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:484–90. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.6.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker CR. A comparison of individual and group therapy as treatment of sexually abused adolescent females. Diss Abstr Int. 1987;47:4319B. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedrich WN, Luecke WJ, Beilke RL, Place V. Psychotherapy outcome of sexually abused boys. J Interpers Violence. 1992;7:396–409. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monck E, Bentovim A, Goodall G, Hyde C, Lewin C. Child Sexual Abuse: A Descriptive and Treatment Outcome Study. London: HMSO; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berliner L, Saunders BE. Treating fear and anxiety in sexually abused children: Results of a controlled 2-year follow-up study. Child Maltreat. 1996;1:294–309. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stauffer LB, Deblinger E. Cognitive behavioural groups for non-offending mothers and their young sexually abused children: A preliminary treatment outcome study. Child Maltreat. 1996;1:65–76. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. A treatment outcome study for sexually abused preschool children: Initial findings. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:42–50. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199601000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Celano M, Hazzard A, Webb C, McCall C. Treatment of traumagenic beliefs among sexually abused girls and their mothers: An evaluation study. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1996;24:1–17. doi: 10.1007/BF01448370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. Interventions for sexually abused children: Initial treatment outcome findings. Child Maltreat. 1998;3:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deblinger E, Lippman J, Steer R. Sexually abused children suffering post-traumatic stress symptoms. Child Maltreat. 1996;1:310–21. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deblinger E, Steer RA, Lippmann J. Two-year follow-up study of cognitive behavioral therapy for sexually abused children suffering post-traumatic stress symptoms. Child Abuse Negl. 1999;23:1371–8. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pithers WD, Gray A, Busconi A, Houchens P. Children with sexual behaviour problems: Identification of five distinct child types and related treatment considerations. Child Maltreat. 1998;3:384–406. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonner BL, Walker CE, Berliner L. Children with Sexual Behaviour Problems: Assessment and Treatment-final Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Clearinghouse on Child Abuse and Neglect; 1999a. [Google Scholar]

- 19.King NJ, Tonge BJ, Mullen P, Myerson N, Heyne D, Rollings S, et al. Treating sexually abused children with posttraumatic stress symptoms: A randomized clinical trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1347–55. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200011000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deblinger E, Stauffer LB, Steer RA. Comparative efficacies of supportive and cognitive behavioral group therapies for young children who have been sexually abused and their nonoffending mothers. Child Maltreat. 2001;6:332–43. doi: 10.1177/1077559501006004006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trowell J, Kolvin I, Weeramanthri T, Sadowski H, Berelowitz M, Glaser D, et al. Psychotherapy for sexually abused girls: Psychopathological outcome findings and patterns of change. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:234–47. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen JA, Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Steer RA. A multisite, randomized controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:393–402. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Knudsen K. Treating sexually abused children: 1 year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29:135–45. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foa EB, McLean CP, Capaldi S, Rosenfield D. Prolonged exposure vs supportive counseling for sexual abuse-related PTSD in adolescent girls: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2650–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosner R, König HH, Neuner F, Schmidt U, Steil R. Developmentally adapted cognitive processing therapy for adolescents and young adults with PTSD symptoms after physical and sexual abuse: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:195. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.House AS. Increasing the usability of cognitive processing therapy for survivors of child sexual abuse. J Child Sex Abus. 2006;15:87–103. doi: 10.1300/J070v15n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dietz TJ, Davis D, Pennings J. Evaluating animal-assisted therapy in group treatment for child sexual abuse. J Child Sex Abus. 2012;21:665–83. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2012.726700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robarts J. Music therapy with sexually abused children. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;11:249–69. doi: 10.1177/1359104506061418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Springer C, Misurell JR, Hiller A. Game-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (GB-CBT) group program for children who have experienced sexual abuse: A three-month follow-up investigation. J Child Sex Abus. 2012;21:646–64. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2012.722592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Habigzang LF, Stroeher FH, Hatzenberger R, Cunha RC, Ramos Mda S, Koller SH. Cognitive behavioral group therapy for sexually abused girls. Rev Saude Publica. 2009;43(Suppl 1):70–8. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102009000800011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tourigny M, Hébert M, Daigneault I, Simoneau AC. Efficacy of a group therapy for sexually abused adolescent girls. J Child Sex Abus. 2005;14:71–93. doi: 10.1300/J070v14n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessler MR, White MB, Nelson BS. Group treatments for women sexually abused as children: A review of the literature and recommendations for future outcome research. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:1045–61. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(03)00165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pagare D, Meena GS, Jiloha RC, Singh MM. Sexual abuse of street children brought to an observation home. Indian Pediatr. 2005;42:134–1139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deb S, Mukherjee A, Mathews B. Aggression in sexually abused trafficked girls and efficacy of intervention. J Interpers Violence. 2011;26:745–68. doi: 10.1177/0886260510365875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Price C. Body-oriented therapy in recovery from child sexual abuse: An efficacy study. Altern Ther Health Med. 2005;11:46–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bohus M, Dyer AS, Priebe K, Krüger A, Kleindienst N, Schmahl C, et al. Dialectical behaviour therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder after childhood sexual abuse in patients with and without borderline personality disorder: A randomised controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2013;82:221–33. doi: 10.1159/000348451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacIntosh HB, Johnson S. Emotionally Focused Therapy for couples and childhood sexual abuse survivors. J Marital Fam Ther. 2008;34:298–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2008.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]