Abstract

Objectives:

Pharmacists are one of the crucial focal points for health care in the community. They have tremendous outreach to the public as pharmacies are often the first-port-of-call. With the increase of ready-to-use drugs, the main health-related activity of a pharmacist today is to assure the quality of dispensing, a key element to promote rational medicine use.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study of 200 pharmacies, 100 each in various residential (R) and commercial (C) areas of Bengaluru, was conducted using a prevalidated questionnaire administered to the chief pharmacist or the person-in-charge by the investigators.

Results:

Dispensing without prescription at pharmacies was 45% of the total dispensing encounters and significantly higher (χ2 = 15.2, P < 0.001, df = 1) in pharmacies of residential areas (46.64%) as compared to commercial areas (43.64%). Analgesics were the most commonly dispensed drugs (90%) without prescription. Only 31% insisted on dispensing full course of antibiotics prescribed and 19% checked for completeness of prescription before dispensing. Although 97% of the pharmacies had a refrigerator, 31% of these did not have power back-up. Only about 50% of the pharmacists were aware of Schedule H.

Conclusion:

This study shows a high proportion of dispensing encounters without prescription, a higher rate of older prescription refills, many irregularities in medication counseling and unsatisfactory storage practices. It also revealed that about half of the pharmacists were unaware of Schedule H and majority of them about current regulations. Hence, regulatory enforcement and educational campaigns are a prerequisite to improve dispenser's knowledge and dispensing practices.

Keywords: Antibiotics, drug dispensing practices, knowledge, medication counseling, storage practices

The Alma-Ata Declaration on Primary Health Care (1978) states that “..health is a fundamental human right and that the attainment of the highest possible level of health is a most important world-wide social goal.” It recognizes the role played by all health-care workers including pharmacists as service provided by them is also a vital component of Primary Health Care.[1] As a step forward, Good Pharmacy Practice (GPP) guidelines for community and hospitals was drafted by the International Pharmaceutical Federation, which was recognized and published by the World Health Organisation (WHO) in 1999.[2]

Safe medication procurement by patients is a global issue. In developing countries, most medications including antibiotics and those with high incidence of side effects, are available without prescription despite regulations.[3,4,5] This may have serious consequences on public health and also contribute to the already prevailing worldwide problem of antibiotic resistance.

The consumption of drugs by patients is often influenced by the dispensing practices and the type of information given during dispensing.[6] Pharmacists can contribute to positive outcomes by educating and counseling patients as studies have repeatedly shown that effective medication counseling can significantly reduce patient nonadherance to prescribed drugs, treatment failure, and wasted health resources.[7,8] On the contrary, inappropriate dispensing or storage of medications can undo many of the benefits of the health-care system.[6]

Community pharmacists have a significant outreach to the public as pharmacies are often the first-port-of-call.[9] Unlike olden times, due to availability of ready-to-use (precompounded) drugs, the main health-related activity of a pharmacist today is to assure quality of dispensing, one of the key elements in promoting rational medicine use.[10] It is recognized and accepted that the conditions of pharmacy practice vary widely from country to country and between different sectors/areas within a country despite existence of GPP guidelines by a recognized body.[1] This study was undertaken to evaluate the drug dispensing practices at pharmacies and current knowledge of pharmacists in both commercial and residential areas of Bengaluru, India.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining approval from institutional ethics committee, a cross-sectional questionnaire-based study was undertaken from August 25, 2014, to September 25, 2014, including 200 pharmacies in various residential (R) and commercial (C) areas of Bengaluru.

Two hundred and twenty-five pharmacies were screened for the study by convenient sampling. A total of 25 pharmacies (R-12, C-13) were not included as they were either not willing to participate or were closed at the time of visit. A total of 200 pharmacies, 100 each in various residential and commercial areas of Bengaluru willing to participate were selected for the study.

The questionnaire was constructed based on GPP guidelines and previous studies.[1,9,11,12,13] It was then validated by face value and expert opinion. It was pretested on twenty pharmacies, and Cronbach's alpha of 0.71 was obtained. The questionnaire had two sections, practice, and knowledge with 14 and 4 questions, respectively.

Informed consent was taken in an attached consent form describing the objectives of the study and participants were assured of confidentiality to elicit an unbiased response. The prevalidated semi-structured questionnaire was administered to the pharmacist or to the person-in-charge in case of nonavailability or absence of the chief pharmacist by the investigators.

Statistical Analysis

The data collected in the form of completed questionnaires was categorized, coded, and analyzed. Data were expressed as percentages/proportions, tests of proportions were done with Chi-square wherever deemed necessary, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Dispensing Practices

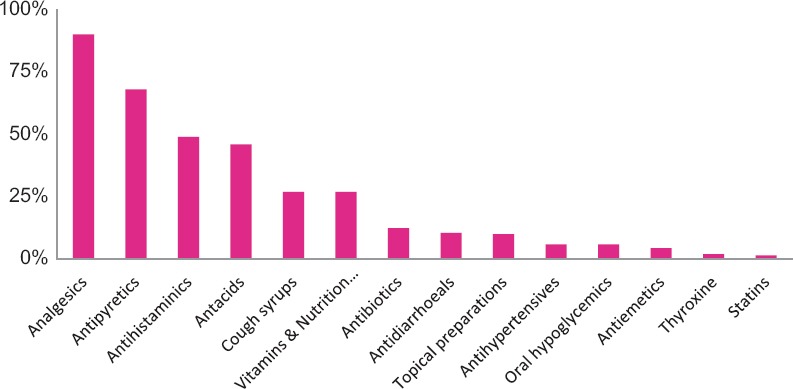

Dispensing without prescription at pharmacies was 45% of the total dispensing encounters, with analgesics (90%) being the most commonly dispensed drugs without prescription followed by antipyretics (68%), antihistaminics (49%), and antacids (46%) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Classes of drugs dispensed without prescription

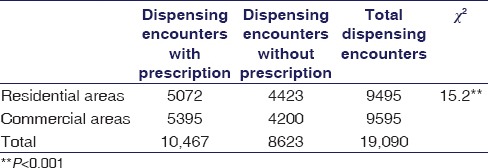

Dispensing without prescription was higher among pharmacies located in residential areas (46.64%) as compared to commercial areas (43.64%), which was statistically significant, χ2 = 15.2, P < 0.001, and df = 1 [Table 1].

Table 1.

Dispensing encounters without prescription in residential and commercial areas of Bengaluru (n=200)

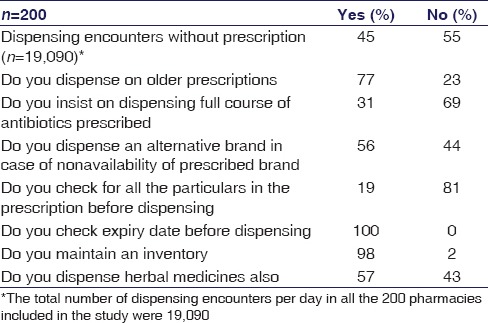

Only about 19% of the pharmacists checked for all the particulars (patient particulars, date of prescription, drug name, drug dose and frequency, signature of the doctor, and register number of the doctor) in the prescription before dispensing the drugs. Almost all of them (98%) maintained an inventory, computerized (41%), and manual (57%) while 2% did not [Table 2].

Table 2.

Dispensing practices at pharmacies in Bengaluru (n=200)

Storage Practices

Although 97% (194) of the pharmacies had a refrigerator, 31% (66) of these did not have power back-up. Sixty-two percent (124) checked the pharmacy for drugs nearing expiry on a monthly basis.

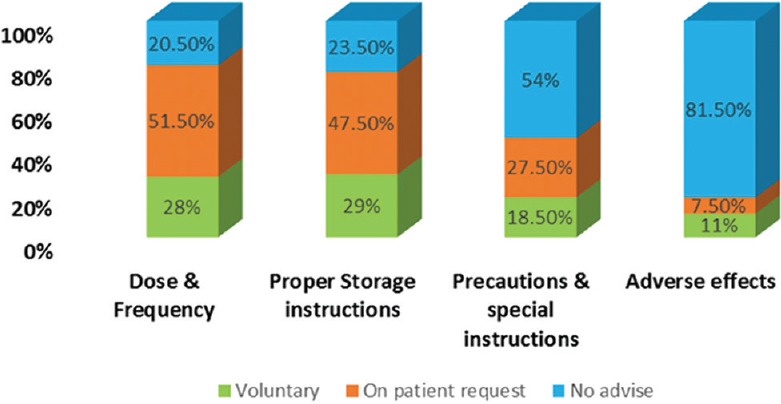

Medication Counseling

The pharmacists advising patients about the various aspects of medication use voluntarily, on patient request or no advice given is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Medication counseling in pharmacies in Bengaluru (n = 200)

Knowledge

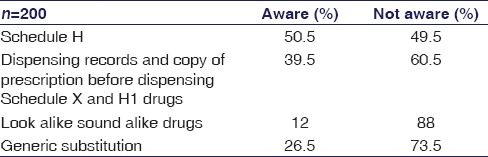

Only 50.5% were aware of Schedule H. About 60.5% did not know that prescription in duplicate and stringent dispensing records have to be maintained while dispensing Schedule X and H1 drugs [Table 3]. Among who knew, 22% thought that they have to be maintained for Schedule X drugs only, 4.5% for Schedule H1 drugs only, and very few (13%) knew that these have to be maintained for both.

Table 3.

Knowledge of the pharmacists in Bengaluru (n=200)

The majority of them did not know about look alike sound alike (LASA) drugs and generic substitution (88% and 73.5%, respectively, [Table 3]).

Discussion

India, with an abysmal doctor-population ratio of 1:1218 (minimum recommended by the WHO being 1:1000) is struggling to cope with the health-care needs of a growing population.[14,15] People rely on alternative health-care professionals such as chemists, traditional medicine practitioners, and faith healers directly to meet their health needs and to reduce personal costs. Hence, pharmacists are one of the crucial focal points for health care in the community. They have a large outreach to the public as the number of people visiting pharmacy outlets is possibly greater than other health-care units. This although provides pharmacists with an opportunity for greater involvement in the health-care system, their fragmentary knowledge and improper dispensing practices may have undesired effects. Indiscriminate dispensing of antibiotics, sub-therapeutic quantities of antibacterials, inappropriate combination of drugs, and injectables under suboptimal conditions have also been reported in the previous studies.[16] Hence, this study was undertaken to evaluate the drug dispensing practices at pharmacies and the knowledge of pharmacists in Bengaluru.

The most important finding in this study was a high proportion (45%) of dispensing encounters without prescription. This dispensing pattern is similar to another study conducted in Tamil Nadu, India, where 58% of the pharmacists dispensed drugs without prescription but better than practices in other countries such as Egypt (72%), Tanzania (77%), and Vietnam (99%) where higher rates of dispensing without prescriptions were documented.[11,12,17,18] While lack of universal access to health care could be a major factor, convenience, reduced time to procure medicines, and cost consumption could also be responsible for this pattern. Furthermore, a higher proportion of dispensing encounters without prescription in the residential areas was observed as compared to the commercial areas. Apart from the reasons cited above, this could be due to a farther location of health-care facilities.

Analgesics, antipyretics, antacids, cold and cough remedies, vitamins, nutrition supplements, and antibiotics constituted commonly dispensed drugs without prescription, in that order. Similar patterns were also seen in the Egypt and Tanzania studies while in the Vietnam study and another study conducted in India,[19] antibiotics, vitamins, and nutrition supplements were most commonly dispensed. In another study conducted in Saudi Arabia, almost all the pharmacists dispensed antibiotics without prescription.[20] Analgesics and antipyretics are the most commonly used drugs for relief of fever, common aches, and pains. Although aspirin and paracetamol can be dispensed without prescription, they can lead to adverse outcomes under certain conditions and hence, there is a need for them to be dispensed at right doses with proper counseling of end users. Other analgesics such as ibuprofen and diclofenac are prescription drugs. While antacids are among over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, most of the cold and cough remedies and all the antibiotics are Schedule H drugs. Some authors have also questioned the appropriateness of widespread use of cold and cough remedies, some vitamin preparations and their irrational combinations.[11] This scenario prevails even in the face of existing regulations as most pharmacies do not adhere to them.[21,22] With bias being a known caveat of questionnaire surveys the actual situation could still be worse.

In the UK, a prescription is valid for 6 months from the date of prescription, unless the medicine prescribed contains a controlled drug, in which case it is valid antibiotics and other drugs as OTC medications. Under the federal law, prescriptions for Schedule III substances expire after 6 months and 5 refills are allowed within the 6-month period, whereas prescriptions for Schedule II controlled substances cannot be refilled.[23]

In this study, it was found that 77% of the pharmacists dispensed drugs for older prescriptions also. This could be due to no specific regulations in place regarding duration of validity of a prescription in our country.

Although antibiotics are an essential tool for modern medicine in combating most of the infections, antibiotic resistance remains to be a worldwide problem. While misuse of antibiotics is a key factor contributing to antibiotic resistance, failure to take an antibiotic as prescribed adds no less. Only one-third of the pharmacists insisted on dispensing full course of the antibiotics prescribed and this improper dispensing can contribute to the growing health hazard of antibiotic resistance, which adds to health-care costs and increased economic burden on the society.[24]

The GPP guidelines by the Indian Pharmaceutical Association require the pharmacist, on receiving the prescription, to confirm the identity of the client, review the prescription for completeness, and check for correctness of the prescribed medications.[13] This is to ensure right dispensing and thus avoid contributing to medication errors at large, the stakes of which are high. However, in this study, 81% of the pharmacists said they would not check for all the particulars. Instead, they would check only those particulars which they perceived as important. However, all of them did check for expiry of the medications before dispensing.

Maintaining an inventory, especially a computerized one, may contribute to efficient dispensing by reducing the dispensing time. In this study, we found that 41% of the pharmacies had a computerized inventory, 57% had manual inventory, and 2% did not maintain one. According to the GPP guidelines pharmacies should preferably be equipped with computers for inventory management.[13]

Herbal medicines have emerged as a common choice of therapy for self-care as they are perceived to be free of side effects. This practice is also enforced by irrational claims and aggressive promotions by manufacturers and media, peer views, and lack of well-documented unbiased studies on herbal drug use in disease conditions. Community pharmacists are major suppliers of complementary herbal medicines. A study conducted in Lagos, Nigeria, showed that community pharmacies frequently supplied herbal medicines.[25] Fifty-seven percent of the pharmacies included in this study also dispensed herbal medicines. In the UK, Human Medicines Regulations 2012 allows only long-established and quality-controlled herbal medicines to be sold. It has also implemented The Traditional Herbal Medicines Registration Scheme for authorizing the marketing of herbal products. Such laws governing the sale of herbal medicines are lacking in our country.

Medication counseling is the duty of the modern community pharmacists through which they can significantly contribute to medication safety and patient compliance.[6,9] The GPP guidelines require the pharmacist to provide professional counseling with regard to the use of medicines, their side effects, and precautions, if any.[13] Recognizing the importance of medication counseling, The North Carolina Board of Pharmacy since 1993 made a rule to offer patient counseling on all new prescriptions. However, a low rate of voluntary medication counseling by the pharmacists was noted in this study. A similar trend appears to prevail in North West Ethiopia also.[6] This could possibly be improved by modifying the attitude of pharmacists through educational interventions, incentives, and regulations.

Drug storage practices, essential for maintaining efficacy of some drugs, were not in accordance with the GPP guidelines which states that pharmacies should be equipped with refrigerated storage facilities validated from time to time for products requiring storage at cold temperature. Also having a refrigerator in the pharmacy is a licensing requirement. About 3% of the pharmacies did not have a refrigerator and about 31% of the pharmacies which had a refrigerator did not have power back-up for the same. This scenario is better than another study conducted in Pakistan where the majority of the pharmacies did not have an alternative power supply for the refrigerator.[4]

Generic substitution is the mutual substitution of medicinal products having the same active ingredient, in the same dose and pharmaceutical form. Legally, there can be no substitution without the physician's consent.[26] This concept especially becomes important in case of biologicals and drugs with narrow therapeutic index. Disasters such as breakthrough seizures in epileptics due to disregard to the concept of generic substitution are well known.[27,28] Nearly, 73.5% of the pharmacists were not aware of the term generic substitution. Nevertheless, unaware of its implications, 56% said they would dispense an alternative brand of the same drug in case of nonavailability of the brand prescribed, irrespective of which drug it was. Although guidelines for the same are in place in few countries, lack of such robust system in our country and unawareness can compound the problems faced in therapeutics.[26]

Indian Pharmaceutical industry is now the third-largest in the world with more than 20,000 registered units. This growth has led to the introduction of various drugs with catchy brand names. The potential for error due to confusing names among health-care personnel has also significantly increased.[29] Pharmacists should, therefore, be cautious while dispensing such drugs and take steps to avoid dispensing errors such as sticking warning labels and avoid keeping LASA drugs in close proximity. However, in this study, the majority (88%) did not know about LASA drugs. In all the pharmacies drugs were arranged according to the alphabetical order of their brand names. These could lead to dispensing errors and their morbid consequences.

Rampant use of antibiotics and other drugs as OTC medications can lead to serious adverse drug reactions and antibiotic resistance. Hence, Schedule H and Schedule X of the Drugs and Cosmetic Rules, 1945, came into being. Schedule H includes substances that could be sold by retail on the prescription of a registered medical practitioner only. Schedule X drugs are those for which a retailer has to preserve the prescription for a period of 2 years. While Schedule X has worked, Schedule H implementation has been lax, necessitating the Schedule H1, with 46 drugs in its purview. Schedule H1 came into effect from March 1, 2014, and contains prescription only drugs for which a copy of the prescription has to be preserved. Only about half of the pharmacists were aware of Schedule H and 17.5% were updated with current regulations on Schedule H1.[22]

Sixty-five percent of the pharmacists are not aware that prescription in duplicate and stringent dispensing records have to be maintained while dispensing Schedule X drugs. Knowledge and updated drug information is a must for people involved in drug dispensing to assure the quality of dispensing. However, most of them obtain their drug information in informal ways such as industry representatives and peers. Thus, given the gap in knowledge of pharmacists and their unawareness of current regulations, their dispensing practices may undo the beneficial effects of the health-care system.

Thus, this study shows lacunae in the knowledge and dispensing practices at pharmacies. However, a drug dispensing audit at pharmacies could have avoided the bias associated with a questionnaire-based study. Furthermore, simple random sampling instead of convenient sampling could have been more representative of all pharmacies in Bengaluru City.

Conclusion

This study revealed improper dispensing practices at pharmacies in both residential and commercial areas of Bengaluru city with a high proportion of dispensing encounters without prescription, a higher rate of older prescription refills and inadequate medication counseling, and storage practices. It also highlights lacunae in the knowledge of pharmacists about Schedule H and current regulations pertaining to Scheduled drugs. A similar scenario seems to prevail elsewhere in India and in other developing countries of the world. Hence, structured educational campaigns, generation, and implementation of OTC list, and regulatory enforcement can better equip pharmacists for their main role of promoting rational drug use.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.International Pharmaceutical Federation. Good Pharmacy Practice (GPP) in Developing Countries. 1997. [Last accessed 2014 Aug 25]. Available from: http://www.fip.org/files/fip/Statements/GPP%20recommendations.pdf .

- 2.International Pharmaceutical Federation. Joint FIP/WHO Guidelines on GPP: Standards for Quality of Pharmacy Services, No. 961, 45th Report of the WHO Expert Committee. 2011. [Last accessed 2014 Aug 25]. Available from: http://www.whqlibdoc.who.int/trs/WHO_TRS_961_eng.pdf .

- 3.Hanafi S, Poormalek F, Torkamandi H, Hajimiri M, Esmaeili M, Khooie SH, et al. Evaluation of community pharmacists’ knowledge, attitude and practice towards good pharmacy practice in Iran. J Pharm Care. 2013;1:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butt ZA, Gilani AH, Nanan D, Sheikh AL, White F. Quality of pharmacies in Pakistan: A cross-sectional survey. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17:307–13. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Faham Z, Habboub G, Takriti F. The sale of antibiotics without prescription in pharmacies in Damascus, Syria. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2011;5:396–9. doi: 10.3855/jidc.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wabe NT, Raju NJ, Angamo MT. Knowledge, attitude and practice of patient medication counseling among drug dispensers in North West Ethiopia. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2011;01:85–90. [Google Scholar]

- 7.ASHP guidelines on pharmacist.conducted patient education and counseling. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/54.4.431. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1997;54:431-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Svarstad BL, Bultman DC, Mount JK. Patient counseling provided in community pharmacies: Effects of state regulation, pharmacist age, and busyness. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2004;44:22–9. doi: 10.1331/154434504322713192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Portugal: Visao Grafica; 2005. International Pharmaceutical Students’ Federation, International Pharmaceutical Federation. Counselling, Concordance and Communication [Pamphlet]. Portugal: Visao Grafica. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caamaño F, Tomé-Otero M, Takkouche B, Gestal-Otero JJ. Influence of pharmacists’ opinions on their dispensing medicines without requirement of a doctor's prescription. Gac Sanit. 2005;19:9–14. doi: 10.1157/13071811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benjamin H, Smith F, Motawi MA. Drugs dispensed with and without a prescription from community pharmacies in a conurbation in Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 1996;2:506–14. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kagashe GA, Minzi O, Matowe L. An assessment of dispensing practices in private pharmacies in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania. Int J Pharm Pract. 2011;19:30–5. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7174.2010.00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Indian Pharmaceutical Association. Good Pharmacy Practice Guidelines. 2002. [Last accessed 2014 Aug 25]. Available from: http://www.ipapharma.org/html/GPP_Guidelines_IPA2002.pdf .

- 14.Deo MG. “Doctor population ratio for India – The reality”. Indian J Med Res. 2013;137:632–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.New Delhi: Central Bureau of Health Intelligence; 2013. Central Bureau of Health Intelligence. National Health Profile. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vinay K. Self-medication, and pharmaceutical marketing in Bombay, India. Soc Sci Med. 1988;47:779–94. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basak SC, Prasad GS, Arunkumar A, Senthilkumar S. An attempt to develop community pharmacy practice: Results of two surveys and two workshops conducted in Tamil Nadu. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2005;67:362–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chuc NT, Tomson G. “Doi moi” and private pharmacies: A case study on dispensing and financial issues in Hanoi, Vietnam. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;55:325–32. doi: 10.1007/s002280050636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenhalgh T. Drug prescription and self-medication in India. Soc Sci Med. 1987;25:307–18. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90233-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Mohamadi A, Badr A, Bin Mahfouz L, Samargandi D, Al Ahdal A. Dispensing medications without prescription at Saudi community pharmacy: Extent and perception. Saudi Pharm J. 2013;21:13–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.4th ed. Ghaziabad: Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2011. Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission. National Formulary of India (NFI) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hazra A. Schedule H1: Hope or hype? Indian J Pharmacol. 2014;46:361–2. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.135945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buppert C. Federal laws on prescribing controlled substances. J Nurse Pract. 2009;5:15–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zweynert A. Drug-resistant TB Threatens to Kill 75 Million People by 2050, Cost !16.7 Trillion. Reuters; 23 March, 2015. [Last accessed 2015 Mar 26]. Available from: http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/03/24/us-health-tuberculosis-economy-idUSKBN0MK00520150324 .

- 25.Oshikoya KA, Oreagba IA, Ogunleye OO, Oluwa R, Senbanjo IO, Olayemi SO. Herbal medicines supplied by community pharmacies in Lagos, Nigeria: Pharmacists’ knowledge. Pharm Pract (Granada) 2013;11:219–27. doi: 10.4321/s1886-36552013000400007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Royal Dutch Pharmacists Association. Guidelines for Generic Substitution. 2012. [Last accessed 2015 Mar 26].

- 27.Berg MJ, Gross RA, Tomaszewski KJ, Zingaro WM, Haskins LS. Generic substitution in the treatment of epilepsy case evidence of breakthrough seizures. Neurology. 2008;71:525–30. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000319958.37502.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welty TE, Pickering PR, Hale BC, Arazi R. Loss of seizure control associated with generic substitution of carbamazepine. Ann Pharmacother. 1992;26:775–7. doi: 10.1177/106002809202600605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keny MS, Rataboli PV. Look-alike and sound-alike drug brand names: A potential risk in clinical practice. Indian J Clin Pract. 2013;23:508–13. [Google Scholar]