Abstract

Introduction

Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) are popular among cigarette smokers; however, it is not known whether the use of ENDS assists or delays quitting cigarettes, especially among certain priority populations. We examined predictors of intention to quit smoking and patterns of dual use of ENDS and traditional cigarettes among priority populations.

Methods

This study used data from a 2014 survey of a national probability sample of 5,717 USA adults. Descriptive statistics were used to examine differences in intention to quit cigarette use among current cigarette smokers (n=1,014) and dual users of cigarettes and ENDS (n=248). Multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted on the overall sample and the subsample of dual users to determine whether dual use (versus cigarette only use) and demographic characteristics predict self-reported intention to quit and having attempted to quit in the past year. Significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Compared to cigarette smokers, dual users were slightly more educated (p<0.05), more likely to intend to quit smoking (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=1.8, p=0.001), and more likely to have attempted to quit smoking in the past year (AOR=1.7, p=0.003). Blacks reported higher intention to quit than Whites (AOR=1.8, p= 0.003). Compared with high school education or less, dual users with some college (AOR = 1.5, p = 0.007) or a college degree (AOR = 2.5, p ≤ 0.0001) had high intention to quit.

Conclusions

Dual users of ENDS and traditional cigarettes are more likely to intend to quit smoking and have recently made quit attempts. If using ENDS contributes to increased smoking cessation among more educated individuals, disparity in smoking by level of education will increase.

Keywords: Electronic nicotine delivery devices, disparity, quit intentions

Introduction

A recent commentary argues that technological innovation such as electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) may widen the existing smoking disparity among socioeconomically disadvantaged groups if measures that improve access to harm-reduction tools are not made available (Kalousova, 2015a, 2015b). Disparities in tobacco use persist, with higher smoking rates and slower declines in prevalence over the last decade among less educated and low income groups (Agaku, et al., 2014; Caraballo, et al., 1998; Garrett, Dube, Trosclair, Caraballo, & Pechacek, 2011; Jamal, et al., 2014; Jamal, et al., 2015; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, & National Cancer Institute, 2014). Women experience greater difficulty quitting compared to men when treated with the nicotine patch; however, no sex differences have been observed for intention to quit (Fagan, et al., 2007; Perkins & Scott, 2008). The rates of ENDS use have increased from 4.9% in 2011 to 15.9% in 2014 among adults who smoke cigarettes (King, Alam, Promoff, Arrazola, & Dube, 2013; McMillen, Gottlieb, Shaefer, Winickoff, & Klein, 2014; Schoenborn CA, 2015). Studies suggest that ENDS use is associated with the perceptions that ENDS are less harmful than cigarettes and that they are effective smoking cessation tools (Brose, Hitchman, Brown, West, & McNeill, 2015; Pepper & Brewer, 2014; Pepper, Emery, Ribisl, Rini, & Brewer, 2015; Pepper, Ribisl, Emery, & Brewer, 2014; Siegel, Tanwar, & Wood, 2011; Tan & Bigman, 2014; Vickerman, Carpenter, Altman, Nash, & Zbikowski, 2013).

However, there are little data on which subpopulations of US adults are using ENDS to quit smoking. The objective of this study is to examine dual use status and sociodemographic predictors that are associated with smokers’ intentions to quit and making quit attempts. For this cross-sectional study, we use intention to quit and making quit attempts as proxy for quitting smoking. To assess the perceived potential benefits of electronic cigarettes among current smokers, we examined the opinions of dual users regarding the health effects of ENDS.

Methods

Study Sample

This study used data from the 2014 Tobacco Products and Risk Perceptions Survey (TPRPS) conducted by the Georgia State University (GSU) Tobacco Center of Regulatory Science. The TPRPS is an annual, cross-sectional survey of a probability sample drawn from GfK’s KnowledgePanel and is weighted to be representative of non-institutionalized US adults. The methodology for this study has been described elsewhere (Weaver, et al., 2016). This study was approved by the GSU Institutional Review Board.

Measures

The respondents’ characteristics were obtained from profile surveys administered by GfK to all KnowledgePanel panelists and included self-reported data on sex, age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, annual household income, and health status. Data on tobacco use, intention to quit, and attempts to stop smoking were collected through a self-report, online questionnaire.

Current smokers were respondents who reported lifetime smoking levels of at least 100 cigarettes and smoking “everyday” or “some days.” Dual users were respondents who currently smoked cigarettes and used ENDS within the past 30 days. We excluded current users of little cigars or cigarillos, large cigars, and hookahs. Intention to quit was categorized as “high intention to quit” or “low intention to quit” using responses from a six-point scale. Responses of planning to quit within 7 days to within a year were categorized as “high intention to quit,” and responses of not planning or will plan to quit someday were categorized as “low intention to quit.” Respondents were asked if they had attempted to quit smoking in the past year (“yes” or “no”). The perception of health benefits from using ENDS was assessed by asking “How much do you think about each of the following now, how using e-cigarettes might improve your health?” Response options were “a lot,” “a little,” “not at all,” and “I don’t know.”

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.3, with significance set a priori at p < 0.05. The SAS survey procedures were used with sample weights to account for the complex survey design. Differences in dual use proportions among smokers by demographic characteristics were examined using chi-squared tests of association. We conducted descriptive statistics to examine differences in intention to quit among cigarette smokers and dual users by educational level, and to examine differences in dual users’ perceptions of how ENDS use may benefit their health by their intention to quit smoking. Multivariable logistic regression models tested whether intention to quit smoking and quit attempts in the past year differed for dual users compared to cigarette-only users. Multivariable logistic regression models were conducted for the overall sample and among the subset of dual users. We further examined sociodemographic factors that were associated with intention to quit and quit attempts.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The study included 1262 current smokers, of which 19% (248) were dual users (i.e., currently using ENDS plus cigarettes). No significant differences in sociodemographic characteristics were observed between cigarette-only users and dual users except for education (p=0.027) (Table 1). A higher proportion of dual users were college graduates compared to cigarette-only smokers.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics by cigarette smoker and dual user status among USA adults, 2014

| Respondent characteristics | Study sample, overall weighted % (weighted N) | a Only cigarette smokers (n=1,014) weighted % (95% CI) | b Dual users (n=248) weighted % (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Sex | 0.864 | |||

| Male | 50.70 (18,305,269) | 50.57 (46.9–54.2) | 51.28 (44.0–58.6) | |

| Female | 49.30 (17,798,396) | 49.43 (45.8–53.1) | 48.72 (41.4–56.0) | |

| Age (years) | 0.085 | |||

| 18–34 | 30.13 (10,877,735) | 28.57 (25.1–32.1) | 36.90 (29.54–44.25) | |

| 35–54 | 41.44 (14,959,465) | 42.40 (38.8–46.0) | 37.27 (30.2–44.3) | |

| >55 | 28.44 (10,266,464) | 29.04 (26.0–32.1) | 25.83 (20.1–31.6) | |

| Race/ ethnicity | 0.079 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 61.55 (22,221,214) | 60.30 (56.6–64.0) | 66.97 (59.6–74.3) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 17.70 (6,391,310) | 19.13 (16.1–22.2) | 11.51 (6.7–16.3) | |

| Others | 20.75 (7,491,141) | 20.57 (17.3–23.8) | 21.52(14.7–28.3) | |

| Education | 0.027 | |||

| High school education or less | 56.95 (20,562,262) | 58.25 (54.8–61.7) | 51.33 (44.1–58.6) | |

| Some college/ vocational | 32.42 (11,703,967) | 32.28 (29.0–35.5) | 33.0 (26.4–39.6) | |

| College graduate | 10.63 (3,837,436) | 9.47 (7.6–11.3) | 15.67 (10.8–20.5) | |

| Household income | 0.172 | |||

| <$30K | 41.70 (15,054,540) | 42.90 (39.2–46.6) | 36.5 (29.3–43.8) | |

| $30K–60K | 31.06 (11,212,724) | 31.04 (27.8–34.3) | 31.15 (24.5–37.8) | |

| >$60K | 27.25 (9,836,400) | 26.08 (23.0–29.1) | 32.31 (25.6–39.0) | |

| Perceived health status | 0.125 | |||

| Excellent /very good | 31.67 (11,094,201) | 30.50 (27.1–33.9) | 36.77 (29.4–44.2) | |

| Good | 45.58 (15,968,796) | 47.14 (43.5–50.8) | 38.73 (31.6–45.8) | |

| Fair /poor | 22.75 (7,971,673) | 22.36 (19.3–25.5) | 24.50 (18.1–30.9) | |

| Presence of children under 18 in the household | 0.413 | |||

| Yes | 32.23 (11,636,313) | 31.62 (28.2–35.0) | 34.88 (27.7–42.1) | |

| No | 67.77 (24,467,352) | 68.38 (65.0–71.8) | 65.12 (57.9–72.3) | |

Cigarette smokers were defined as those who were current cigarette smokers only;

Dual users were defined as those who were current cigarette smokers and current users of electronic nicotine delivery systems; CI, confidence interval.

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p-value<0.05).

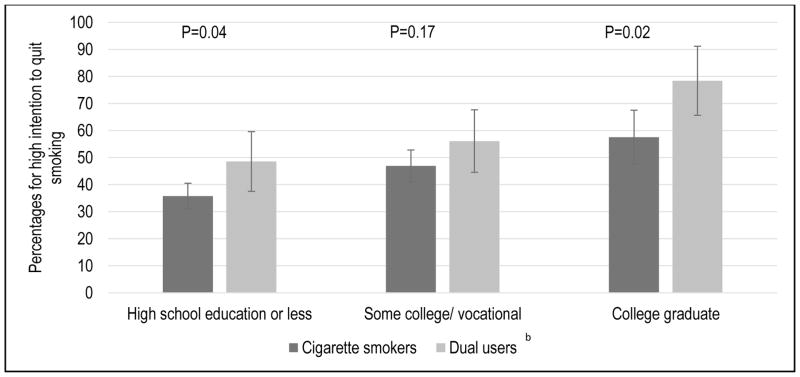

The percentage reporting a high intention to quit differed significantly between cigarette smokers and dual users and across education levels (data not shown). A higher proportion of dual users had high intention to quit compared to cigarette smokers. Having high intention to quit was significant among participants with high school education or less (p = 0.04) and college graduates (p = 0.02) (Fig. A.1).

Intention to quit

In multivariable analyses, dual users were more likely to have a high intention to quit smoking (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=1.79, 95% CI=1.27–2.54). Blacks (non-Hispanic) were more likely to report a high intention to quit than Whites (non-Hispanic) (AOR=1.81, 95% CI=1.22–2.67). Compared with high school education or less, those with a college degree (AOR=2.46, 95% CI=1.61–3.77) and some college/vocational education (AOR=1.5, 95% CI=1.12–2.0) had greater odds of high intention to quit. Odds of intention to quit did not vary significantly by gender, age, income, or health status (Table 2, model 1). Dual smokers with a college degree were significantly more likely to have a high intention to quit smoking compared to those with high school education or less (AOR 4.74; 95% CI, 1.71–13.15) (Table 2, model 2).

Table 2.

Associations between smoker’s status and sociodemographic characteristics by intention to quit smoking and quit attempts

| Characteristics | High intention to quit smoking AOR (95% CI) |

Attempted to quit smoking AOR (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

|

b Model 1 Overall sample (n = 1262) |

c Model 2 Dual users (n = 248) |

b Model 1 Overall sample (n = 1262) |

c Model 2 Dual users (n = 248) |

||

|

| |||||

| Smoker Status | Only cigarettes | Ref | - | Ref | - |

| a Dual user | 1.79 (1.27–2.54)*** | - | 1.70 (1.21–2.40)** | - | |

| Gender | Male | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Female | 1.20 (0.91–1.56) | 0.92 (0.49–1.72) | 1.07 (0.81–1.42) | 1.23 (0.64–2.39) | |

| Age | <35 years | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 35–54 years | 0.86 (0.61–1.22) | 0.79 (0.38–1.66) | 0.75 (0.52–1.07) | 0.60 (0.28–1.27) | |

| >55 years | 0.99 (0.70–1.42) | 0.77 (0.35–1.68) | 0.76 (0.53–1.10) | 0.43 (0.20–0.96)* | |

| Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic White | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.81 (1.22–2.67)** | 1.88 (0.63–5.62) | 1.58 (1.06–2.35)* | 1.80 (0.68–4.76) | |

| Others | 1.07 (0.73–1.57) | 0.47 (0.21–1.05) | 1.70 (1.15–2.51)** | 1.18 (0.51–2.73) | |

| Education | High school education or less | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Some college/ vocational | 1.50 (1.12–2.00)** | 1.50 (0.76–2.97) | 1.01 (0.75–1.38) | 0.68 (0.33–1.39) | |

| College graduate | 2.46 (1.61–3.77)*** | 4.74 (1.71–13.15)** | 1.54 (1.01–2.37)* | 2.75 (1.16–6.49)* | |

| Annual Household Income | <$30 K | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| $30 to <60K | 1.27 (0.91–1.77) | 0.58 (0.26–1.29) | 0.91 (0.64–1.28) | 0.92 (0.41–2.07) | |

| >$60K | 1.34 (0.93–1.93) | 0.54 (0.23–1.27) | 0.90 (0.61–1.31) | 0.59 (0.25–1.42) | |

| General Health Status | Excellent/very good | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Good | 0.94 (0.69–1.29) | 0.98 (0.47–2.01) | 1.16 (0.84–1.60) | 1.07 (0.53–2.16) | |

| Fair/poor | 0.79 (0.54–1.18) | 0.66 (0.28–1.59) | 0.80 (0.53–1.21) | 0.51 (0.20–1.32) | |

p-value <0.05;

p-value <0.01;

p-value <0.001

Dual users were defined as those who were current cigarette smokers and current users of electronic nicotine delivery systems;

Model 1: Multivariable logistic regression among cigarette users and dual users;

Model 2: Multivariable logistic regression among dual users only

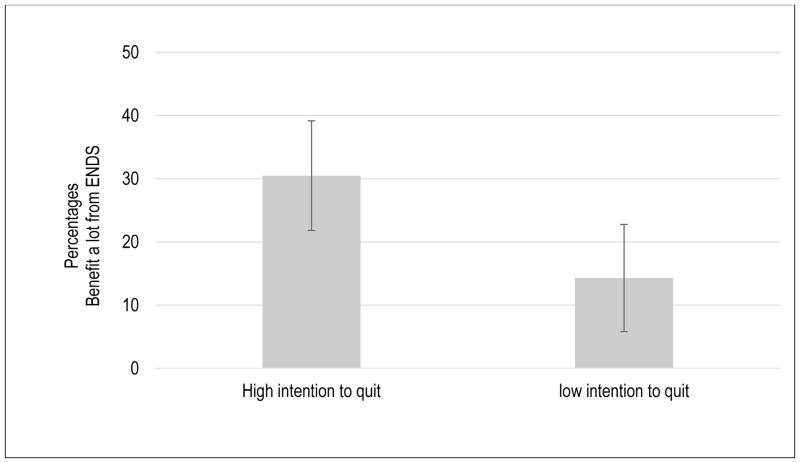

Compared to dual users with a low intention to quit (14%), those with a high intention to quit (30%) were significantly more likely to believe that e-cigarette use might improve their health (p = 0.024) (Fig. A.2).

Quit attempts

In multivariable analyses, dual users were more likely to have attempted to quit smoking in the past year (AOR=1.70; 95% CI=1.21–2.40) than smokers of only cigarettes. Compared to Whites, Blacks reported higher odds of having made quit attempts in the past year (AOR=1.58; 95% CI, 1.06–2.35) (Table 2, model 1). Among dual users, having a college degree was associated with higher odds of having attempted to quit smoking in the past year (AOR= 2.75; 95% CI, 1.16–6.49) (Table 2, model 2).

Discussion

Findings from this study suggest that dual users and those with high educational attainment were more likely to have higher intention to quit and attempts to quit smoking. Among dual users, having a college degree was associated with high intention to quit smoking and attempting to quit in the past year. This study highlights patterns in ENDS use that may increase the socioeconomic gap in smoking prevalence as marked by educational differences in the intention to quit and making quit attempts.

Previous research has associated long-term smoking cessation with motivation to quit, having attempted to quit, and using evidence-based smoking cessation aids (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, et al., 2014). These findings are similar to those from another study in which ENDS use was associated with high intention to quit smoking (Rutten, et al., 2015). The authors found a high level of ENDS use among college graduates as well as proportionally less use among Blacks and other minorities compared to Whites. Consistent with that study (Rutten, et al., 2015), we found that current smokers used ENDS with an intention to quit smoking cigarettes or reduce the use of combustible cigarettes. If ENDS use proves to be helpful for smoking cessation among long-term smokers, then interventions to improve access to ENDS among minority smokers and those with low levels of education may be needed to reduce smoking-related disparities (Kalousova, 2015a, 2015b). In addition, this finding underscores the need for ongoing surveillance to monitor the long-term implication and effectiveness of ENDS as a cessation tool among dual users who desire to quit smoking conventional cigarettes.

Limitations

These data are cross-sectional and self-reported, which makes it difficult to assess the actual rates of smoking cessation among ENDS users or how much dual use may be delaying smoking cessation or leading to actual quitting in the future. Self-reported data have potential recall and reporting biases. The study used an online panel, some of whom had participated in prior tobacco research; however, GfK data suggest minimal panel conditioning from participation in prior tobacco research, which helps mitigate this concern.

Conclusions

This study provides estimates of dual use patterns and the intention to quit smoking cigarettes among the US adult population. It suggests that dual users have high intention to quit smoking, but a smoking disparity related to cessation may still exist among adults with less education. Determining pathways underlying these disparities associated with education level and developing strategies to eliminate them may help reduce health inequalities among smokers. Future research should focus on determining whether high intention to quit smoking is associated with future cessation among dual users of ENDS.

Highlights.

Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) are being used by more smokers.

Dual use of ENDS and cigarettes was studied in 2014 national survey of US adults.

Dual users were more likely to have attempted to quit in past year.

More educated dual users more like to have tried to quit cigarettes.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant number P50DA036128 from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and Food and Drug Administration, Center for Tobacco Products. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the FDA or NIH/NIDA. The authors of this paper report no other financial disclosures.

Appendices

Figure A.1.

Intention to quita smoking cigarettes among cigarette smokers and dual user by educational

aResponses of planning to quit within 7 days to within a year were categorized as “high intention to quit” and responses of not planning or will plan to quit someday were categorized as “low intention to quit.”

bDual users were defined as those who were current cigarette smokers and current users of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS)

Figure A.2.

Electronic nicotine delivery systems would benefit future health among dual usersa

aDual users were defined as those who were current cigarette smokers and current users of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS)

Footnotes

Contributors Nayak: study design, study methodology, data analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript

Terry Pechacek: study design, summaries of previous research studies, interpretation of the findings and revisions on the subsequent drafts

Weaver: study design, statistical analysis and revisions on the subsequent drafts

Eriksen: study design, interpretation of the findings and revisions on the subsequent drafts

All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Role of Funding Sources

This study was supported by grant number P50DA036128 from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and Food and Drug Administration, Center for Tobacco Products. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the FDA or NIH/NIDA. The authors of this paper report no other financial disclosures.

Conflict of Interest Drs. Pechacek and Eriksen receive unrestricted research funding support from Pfizer, Inc. (“Diffusion of Tobacco Control Fundamentals to Other Large Chinese Cities” Michael Eriksen, Principal Investigator). No conflict of interest were reported by the other authors (Drs. Nayak and Weaver) of this paper. The authors declare that there are no other financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work, particularly electronic cigarette companies, and there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agaku IT, King BA, Husten CG, Bunnell R, Ambrose BK, Hu SS, Holder-Hayes E, Day HR Centers for Disease C and Prevention. Tobacco product use among adults--United States, 2012–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:542–547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brose LS, Hitchman SC, Brown J, West R, McNeill A. Is the use of electronic cigarettes while smoking associated with smoking cessation attempts, cessation and reduced cigarette consumption? A survey with a 1-year follow-up. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2015;110:1160–1168. doi: 10.1111/add.12917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caraballo RS, Giovino GA, Pechacek TF, Mowery PD, Richter PA, Strauss WJ, Sharp DJ, Eriksen MP, Pirkle JL, Maurer KR. Racial and ethnic differences in serum cotinine levels of cigarette smokers: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1991. JAMA. 1998;280:135–139. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan P, Augustson E, Backinger CL, O’Connell ME, Vollinger RE, Jr, Kaufman A, Gibson JT. Quit attempts and intention to quit cigarette smoking among young adults in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1412–1420. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.103697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett BE, Dube SR, Trosclair A, Caraballo RS, Pechacek TF. Cigarette smoking - United States, 1965–2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60(Suppl):109–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, Agaku IT, O’Connor E, King BA, Kenemer JB, Neff L. Current cigarette smoking among adults--United States, 2005–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:1108–1112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, Homa DM, O’Connor E, Babb SD, Caraballo RS, Singh T, Hu SS, King BA. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults - United States, 2005–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1233–1240. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6444a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalousova L. E-cigarettes: a harm-reduction strategy for socioeconomically disadvantaged smokers? Lancet Respir Med. 2015a;3:598–600. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalousova L. The real challenge is to make e-cigarettes accessible for poor smokers - Author’s reply. Lancet Respir Med. 2015b;3:e30. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00332-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King BA, Alam S, Promoff G, Arrazola R, Dube SR. Awareness and ever-use of electronic cigarettes among U.S. adults, 2010–2011. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:1623–1627. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen RC, Gottlieb MA, Shaefer RM, Winickoff JP, Klein JD. Trends in Electronic Cigarette Use Among U.S. Adults: Use is Increasing in Both Smokers and Nonsmokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepper JK, Brewer NT. Electronic nicotine delivery system (electronic cigarette) awareness, use, reactions and beliefs: a systematic review. Tob Control. 2014;23:375–384. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepper JK, Emery SL, Ribisl KM, Rini CM, Brewer NT. How risky is it to use e-cigarettes? Smokers’ beliefs about their health risks from using novel and traditional tobacco products. J Behav Med. 2015;38:318–326. doi: 10.1007/s10865-014-9605-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepper JK, Ribisl KM, Emery SL, Brewer NT. Reasons for starting and stopping electronic cigarette use. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:10345–10361. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111010345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Scott J. Sex differences in long-term smoking cessation rates due to nicotine patch. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1245–1250. doi: 10.1080/14622200802097506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutten LJ, Blake KD, Agunwamba AA, Grana RA, Wilson PM, Ebbert JO, Okamoto J, Leischow SJ. Use of e-Cigarettes among Current Smokers: Associations among Reasons for Use, Quit Intentions, and Current Tobacco Use. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutten LJ, Blake KD, Agunwamba AA, Grana RA, Wilson PM, Ebbert JO, Okamoto J, Leischow SJ. Use of E-Cigarettes Among Current Smokers: Associations Among Reasons for Use, Quit Intentions, and Current Tobacco Use. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:1228–1234. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenborn CA, GR N. C. f. H. Statistics, editor. Electronic cigarette use among adults: United States, 2014. Hyattsville, MD: U. S. Government; 2015. (Vol. NCHS Data Brief) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel MB, Tanwar KL, Wood KS. Electronic cigarettes as a smoking-cessation: tool results from an online survey. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:472–475. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan AS, Bigman CA. E-cigarette awareness and perceived harmfulness: prevalence and associations with smoking-cessation outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, & National Cancer Institute; Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion & Office on Smoking and Health (Eds.), editor The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vickerman KA, Carpenter KM, Altman T, Nash CM, Zbikowski SM. Use of electronic cigarettes among state tobacco cessation quitline callers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:1787–1791. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver SR, Majeed BA, Pechacek TF, Nyman AL, Gregory KR, Eriksen MP. Use of electronic nicotine delivery systems and other tobacco products among USA adults, 2014: results from a national survey. Int J Public Health. 2016;61:177–188. doi: 10.1007/s00038-015-0761-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]