Abstract

Background

Ethanol is a tumor promoter and may enhance the metastasis of breast cancer. However, the underlying cellular / molecular mechanisms remain unknown. Amplification of ErbB2 or HER2, a receptor tyrosine kinase of the ErbB family, is found in 20 to 30% of patients with breast cancer. We have previously demonstrated that the effect of ethanol on the migration / invasion of breast cancer cells positively correlated with the expression levels of ErbB2. Adhesion to the extracellular matrix (ECM) is an important initial step for cancer cell invasion and metastasis. In this study, we investigated the effects of ethanol on the adhesion of MCF7 breast cancer cells over-expressing ErbB2 (MCF7ErbB2) to human plasma fibronectin.

Methods

To test the hypothesis that ethanol may enhance the attachment of human breast cancer cells to fibronectin, an important component of the ECM, we evaluated the effect of ethanol on the expression of focal adhesions, cell attachment, and ErbB2 signaling in cultured MCF7ErbB2 cells.

Results

Exposure to ethanol drastically enhanced the adhesion of MCFErbB2 cells to fibronectin and increased the expression of focal adhesions. Ethanol induced phosphorylation of ErbB2 at Tyr1248, FAK at Tyr861, and cSrc at Try216. Ethanol promoted the interaction among ErbB2, FAK, and cSrc, and the formation of a focal complex. AG825, a selective ErbB2 inhibitor, attenuated the ethanol-induced phosphorylation of ErbB2 and its association with FAK. Furthermore, AG825 blocked ethanol-promoted cell / fibronectin adhesion as well as the expression of focal adhesions.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that ethanol enhances the adhesion of breast cancer cells to fibronectin in an ErbB2-dependent manner, and the FAK pathway plays an important role in ethanol-induced formation of a focal complex.

Keywords: Alcohol, Focal Adhesion, Metastasis, Migration, Tumorigenesis

Excessive alcohol consumption has been identified as a significant risk factor for cancers in humans (Boffetta and Hashibe, 2006; McKillop and Schrum, 2005; Ogden, 2005; Poschl and Seitz, 2004; Purohit et al., 2005; Rohrmann et al., 2009; Seitz and Becker, 2007). There is a positive correlation between chronic alcohol exposure and the risk of human breast cancer (Key et al., 2006; Seitz and Becker, 2007; Seitz and Maurer, 2007; Tjonneland et al., 2007; Visvanathan et al., 2007). Epidemiological studies indicate that alcohol consumption is associated with advanced and invasive breast tumors (Vaeth and Satariano, 1998;Weiss et al., 1996). Epidemiological data are supported by experimental studies using animal models and cell culture systems. These experimental studies show that ethanol promotes mammary tumorigenesis, stimulates migration / invasion as well as proliferation of breast tumor cells, and enhances epithelial–mesenchymal transition (Aye et al., 2004; Fan et al., 2000; Forsyth et al., 2010; Izevbigie et al., 2002; Ke et al., 2006; Luo, 2006; Luo and Miller, 2000; Ma et al., 2003; Meng et al., 2000; Singletary, 1997; Watabiki et al., 2000). The mechanisms underlying ethanol-induced promotion of mammary tumors, however, are unclear. We previously demonstrated that the stimulatory effect on the migration / invasion of breast cancer depends on the expression levels of ErbB2/ HER2; ethanol preferably stimulates the migration / invasion of breast cancer cells over-expressing ErbB2 (Aye et al., 2004; Ke et al., 2006;Ma et al., 2003).

The ErbB family of receptor kinases includes 4 closely related members: epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR or ErbB1), ErbB2, ErbB3, and ErbB4. Among the family, ErbB2 or HER2 is most directly related to breast cancer. Amplification of ErbB2 is found in 20 to 30% of patients with breast cancer and is associated with poor prognosis and relapse (Paterson et al., 1991; Slamon et al., 1987). Overexpression or activation of ErbB2 is positively correlated with enhanced invasive potential of breast cancer cells and lymph node metastasis in patients with breast cancer (Arora et al., 2008; Lacroix et al., 1989; Tauchi et al., 1989). Although no known ligand has been identified, ErbB2 is the preferred heterodimerization partner for all ErbB family members, and it plays a pivotal role in intracellular signaling mediated by other ErbB receptors (Graus-Porta et al., 1997). ErbB2 is necessary for the induction of carcinoma cell invasion by ErbB family receptor tyrosine kinases (Spencer et al., 2000). It has been suggested that the focal adhesion kinase (FAK)/ Src pathway plays an important role in ErbB2 regulation of the migration/ invasion of breast cancer cells (Vadlamudi et al., 2002, 2003).

FAK, a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase and a substrate of cSrc, localizes at focal adhesion sites where cells attach to the extracellular matrix (ECM). FAK not only is a signaling protein, but also functions as a scaffold protein for other structural proteins, such as paxillin, Grb2 or p130cas. FAK interacts with these proteins and forms the focal adhesion complex that transmits signals elicited from the ECM. These signals regulate diverse cellular activities, such as cell adhesion, migration, survival, and angiogenesis (van Nimwegen and van de Water, 2007). FAK is involved in tumorigenesis and cancer cell metastasis. Over-expression / activation of FAK is linked to the oncogenic transformation and metastasis of various cancers, including breast cancer (Bai et al., 2009; Hanada et al., 2005; Lacoste et al., 2005; Owens et al., 1995, 1996; Sood et al., 2004).

Metastasis of cancer cells consists of multiple sequential processes. Adhesion of cancer cells to the ECM and cell /ECM interaction is an important step of metastasis. We hypothesize that ethanol promotes the adhesion of cancer cells to the ECM in an ErbB2-dependent manner. Fibronectin is an important component of the ECM. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the effect of ethanol on the cell /fibronectin interaction in MCF7 human breast cancer cells over-expressing ErbB2 (MCF7ErbB2 cells) and underlying mechanisms. We demonstrate here that ethanol promotes the adhesion of MCF7ErbB2 cells to fibronectin and enhances ErbB2 /FAK interaction. Our results suggest that ErbB2/ FAK interaction plays an important role in ethanol-induced cancer cell adhesion to fibronectin and subsequent migration/ invasion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Human plasma fibronectin was obtained from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA). Protein A/G beads were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (San Diego, CA). Anti-paxillin and phospho-FAK (Tyr397) antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen Corporation (Carlsbad, CA). Anti-phospho-Her2 / ErbB2 (Tyr1248) (polyclonal) and ErbB2 (polyclonal) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology Inc. (Beverly, MA). Anti-Neu / Her2 /ErbB2 (monoclonal), FAK, cSrc, and phospho-Src (Tyr216) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-phospho-Her2 / ErbB2 (Tyr1248) (monoclonal) and phospho-FAK (Tyr861) antibodies were purchased from Biosource (Camarillo, CA). Anti-p130Cas antibody was obtained from BD Transduction Laboratory (San Jose, CA). Anti-GAPDH antibody was obtained from Research Diagnostics, Inc. (Concord, MA). Alexa Fluorlabeled secondary antibodies and Prolong Gold anti-fade reagent were obtained from Invitrogen Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Tyrphostin AG825 was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Anti-phospho-cSrc (Tyr416) was kindly provided by Dr. Daniel Flynn (Marry Babb Randolph Cancer Center, Morgantown, WV). All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO).

Cell Culture and Ethanol Exposure

MCF7 and MCF7ErbB2 cells were grown in DMEM medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/ ml) / streptomycin (100 U/ ml), 1 μg /ml hydrocortisone, and 10 μg / ml insulin at 37°C with 5% CO2. A method utilizing sealed containers was used to maintain ethanol concentrations in the culture medium. With this method, ethanol concentrations in the culture medium can be accurately maintained (Luo and Miller, 1997). We have previously established a concentration-dependent effect of ethanol on cell migration / invasion (Luo and Miller, 2000). A pharmacologically relevant concentration of ethanol (400 mg / dl) was used in this study. In general, the concentration for in vitro studies is higher than that required to produce a similar effect in vivo (Luo et al., 2001). The containers were placed in a humidified environment and maintained at 37°C with 5%CO2.

Analysis of Cell Adhesion

Cell adhesion to fibronectin was assayed as described previously (Grimaldi et al., 2006; Wang et al., 1999). Briefly, 96-well cell culture plates were precoated with fibronectin (10 μg / ml) for 60 minutes at 370176C. The plates were then incubated with 3% BSA in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 minutes to block nonspecific binding sites, followed by several washes with PBS. Cells were exposed to ethanol for specified times. After ethanol exposure, cells (5 × 104 / well) were seeded on fibronectin-precoated plates, allowing for attachment for 1 or 3 hours at 37°C with 5% CO2. Nonadherent cells were removed by wash with PBS. The attached cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes, washed 3 times in PBS, and stained with 0.1% crystal violet in 2% ethanol for 10 minutes. Stained cells were rinsed with water and dried. Crystal violet was eluted in 10% acetic acid, and the absorbance (attached cells) was measured at 600 nm using a microtiter platereader.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

The procedure for immunofluorescence microscopy has been previously described (Xu et al., 2007). Briefly, after exposure to ethanol, cells were seeded on fibronectin (10 μg /ml) precoated coverslips. Cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes, washed 3 times in PBS, and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 minutes. Cells were blocked with 5% BSA and incubated with primary antibodies for 1 hour. The concentrations of primary antibodies are: FAK, 1:100; phospho-FAK (Tyr861), 1:50; phospho-ErbB2 (Tyr1248), 1:50; Paxillin, 1:800. Following incubation with primary antibodies, cells were washed and treated with Alexa Fluor-labeled secondary antibodies and rinsed several times with PBS containing Mg2+ and Ca2+. Coverslips were mounted with Prolong Gold anti-fade reagent, and immunofluorescence images were examined with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). The fluorescent signals were measured with the same pinhole, detector gain, and amplifier offset. The number of focal adhesions that was revealed by paxillin immunostaining was counted randomly on 12 or more cells.

Preparation of Cell Lysates and Immunoblotting

After exposure to ethanol, cells were trypsinized and aliquoted cells were seeded on fibronectin (10 μg / ml) precoated dishes, allowing for attachment for indicated times. Cells were then rinsed twice in cold PBS to remove nonadherent cells. Attached cells were lysed in modified RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, 1% NP-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate) containing 1 mM sodium vanadate, 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 5 μg / ml of aprotinin, and 2 μg / ml of leupeptin. The procedure for immunoblotting has been previously described (Ma et al., 2003). Briefly, equal amount of protein samples (40 μg) was clarified by centrifugation at 21,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C and resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE). The separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were probed with indicated primary antibodies, followed by the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and developed by enhanced chemiluminescence. The intensity of specific proteins imaged in the film was quantified using Carestream Molecular Image Software (Carestream Health Inc., Rochester, NY).

Immunoprecipitation

Equal amounts of proteins (about 500 to 800 μg) were incubated with anti-ErbB2, FAK, p130Cas or cSrc antibodies for 2 hours at 4°C, followed by treatment with Protein A/G beads conjugated to agarose for 1 hour at 4°C. Immunoprecipitates were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Samples were washed 5 times with RIPA buffer, 1 time with cold-PBS and boiled in sample buffer (187.5 mM Tri–HCl, pH 6.8, 6% SDS, 30% glycerol, 150 mM DTT, and 0.03% bromophenol blue). Proteins were resolved in SDS–PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting.

Statistics

Differences among treatment groups were tested using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Differences in which p was less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. In cases where significant differences were detected, specific post-hoc comparisons between treatment groups were examined with Student–Newman–Keuls tests.

RESULTS

Ethanol Enhances the Adhesion of Breast Cancer Cells to Fibronectin

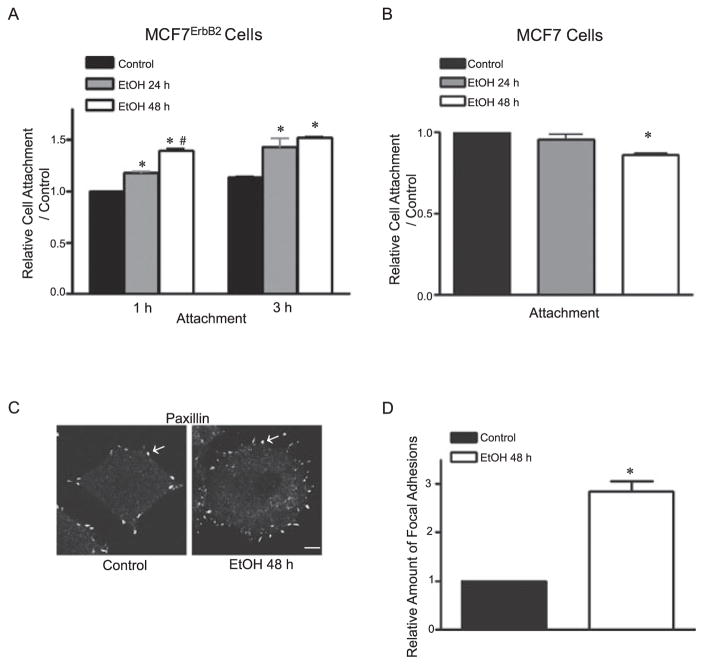

We have previously demonstrated that ethanol preferably stimulated the migration/ invasion of breast cancer cells overexpressing ErbB2 (Aye et al., 2004; Ke et al., 2006; Ma et al., 2003). Because adhesion of cancer cells to the ECM is an important initial step for their migration / invasion, we sought to determine whether ethanol affects the adhesion of breast cells to the ECM. In this experiment, we investigated the effect of ethanol on the adhesion of MCF7ErbB2 cells to fibronectin. MCF7ErbB2 cells were pretreated with ethanol (0 or 400 mg/ dl) for 24 or 48 hours and allowed to attach to fibronectin for 1 or 3 hours. As shown in Fig. 1A, pretreatment of ethanol significantly enhanced the adhesion of MCF7ErbB2 cells to fibronectin. For the cells that were allowed to attach to fibronectin for 1 hour, ethanol-promoted cell adhesion was duration dependent; the increase in cell adhesion caused by 48 hours of ethanol pretreatment was significantly more than that induced by 24 hours of ethanol pretreatment (Fig. 1A). Because the formation of focal adhesion signalosomes is directly required for attachment, motility, and spreading activity of cells (Parsons, 2003; Wehrle-Haller and Imhof, 2002), we examined the effect of ethanol on focal adhesions. We used paxillin immunoreactivity to visualize focal adhesions. Paxillin is a key partner and substrate of FAK in focal adhesion sites, and its immunoreactivity has been used to evaluate focal adhesions (Bailey and Liu, 2008; Kassis et al., 2006). As shown in Fig. 1C,D, ethanol caused a 3-fold increase in the number of focal adhesions. Ethanol had little effect on cell adhesion in parental MCF7 cells; in fact, ethanol (48 hours) caused a modest inhibition of cell adhesion (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Effect of ethanol on the attachment and focal adhesions of breast cancer cells. (A) MCF7ErbB2 cells were pretreated with ethanol (0 or 400 mg/ dl) for 24 or 48 hours and seeded on fibronectin-coated culture wells. After 1 or 3 hours of incubation, cell adhesion to fibronectin was determined as described under the Materials and Methods. The number of adherent cells was presented relative to untreated controls. Each data point was the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. (B) MCF7 cells were pretreated with ethanol (0 or 400 mg/ dl) for 24 or 48 hours and seeded on fibronectin-coated culture wells for 3 hours. Cell adhesion to fibronectin was determined as described above. (C) Cells were pretreated with ethanol (0 or 400 mg / dl) for 48 hours and plated on fibronectin-coated glass coverslips, allowing attachment for 3 hours. Focal adhesions were detected by immunofluorescent staining for paxillin and visualized by confocal microscopy as described under the Materials and Methods. Focal adhesions were indicated by arrows. Scale bar = 5 μm. (D) Focal adhesions were counted randomly on 12 or more cells. The mean of focal adhesions per cell was calculated and expressed relative to untreated controls. Each data point was the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. *Significant difference from untreated controls. #Significant difference from 24-hour pretreatment group.

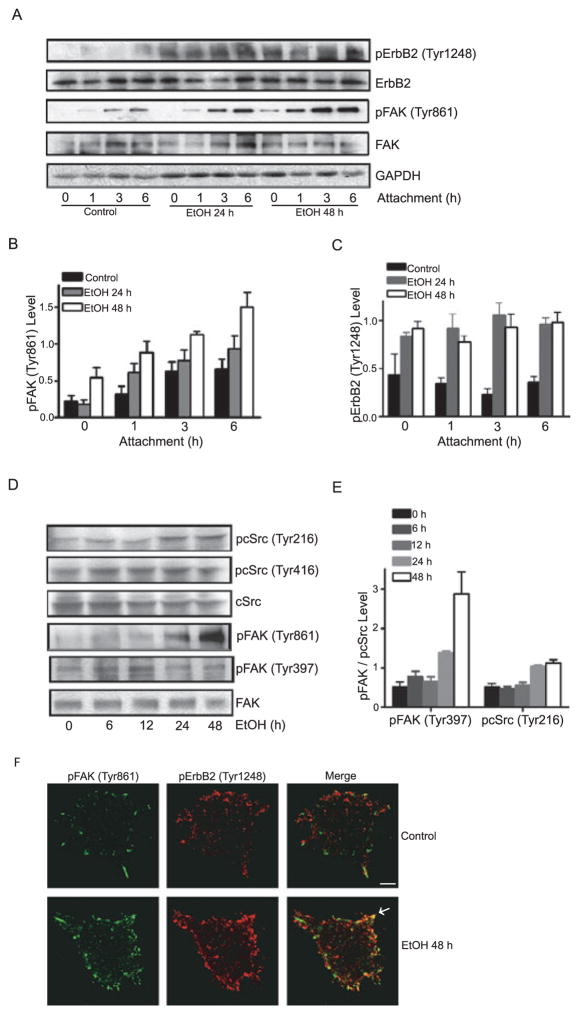

Ethanol Induces Phosphorylation of ErbB2, FAK, and cSrc

Because breast cancer cells expressing high levels of ErbB2 are more sensitive to ethanol, we sought to determine whether ethanol promotes ErbB2 activation and examine the effect of ethanol on ErbB2 phosphorylation. As shown in Fig. 2A,C, pretreatment with ethanol increased the phosphorylation of ErbB2 at Tyr1248 in MCF7ErbB2 cells. The effect of ethanol was similar between the group of 24 and 48 hours of pretreatment. It appeared that ethanol-induced ErbB2 phosphorylation was independent of the interaction with fibronectin because elevated pErbB2 (Tyr1248) levels were detected before the cells were seeded to fibronectin-coated culture dishes. Expression levels of ErbB2 in parental MCF7 cells were low and ethanol did not affect ErbB2 phosphorylation in these cells (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Effect of ethanol on the phosphorylation of ErbB2, FAK, and cSrc. (A) MCF7ErbB2 cells were pretreated with ethanol (0 or 400 mg/ dl) for 24 or 48 hours. Cells were seeded on fibronectin-coated dishes and allowed to attach for 1 to 6 hours. Cells were harvested after specified times of attachment and analyzed for the phosphorylation of ErbB2, FAK, and cSrc with immunoblotting. Expression of GAPDH served as a loading control. (B and C): The relative levels of pFAK and pErbB2 were quantified as described under the Materials and Methods and normalized to the expression of FAK and ErbB2, respectively. (D) Cells were pretreated with ethanol (0 or 400 mg/ dl) for 6 to 48 hours and allowed to attach for 3 hours. Cell lysates were collected and analyzed for the phosphorylation of FAK and cSrc with immunoblotting. (E) The relative levels of pFAK and pcSrc were quantified and normalized to the expression of FAK and cSrc, respectively. (F) Cells were pretreated with ethanol (0 or 400 mg / dl) for 48 hours and plated to fibronectin-coated coverslips, allowing attachment for 1 hour. Phosphorylation of FAK (Tyr861) and ErbB2 (Tyr1248) was detected with immunofluorescent staining. Arrows indicate the co-localization of pErbB2 and pFAK. Scale bar = 5 μm. These experiments were replicated 3 times.

Because FAK plays a pivot role in cell /ECM interaction and the formation of focal adhesions, we next examined the effect of ethanol on FAK. Ethanol pretreatment drastically increased the phosphorylation of FAK at Tyr861; cells undergoing 48 hours of ethanol pretreatment displayed a higher increase in pFAK (Tyr861) compared to cells pretreated for 24 hours (Fig. 2A,B). The phosphorylation of FAK at Tyr861 depended on cell /fibronectin interaction. In untreated cells, the levels of pFAK (Tyr861) increased as cells attached to fibronectin; among the time points examined, cells displayed highest levels of pFAK (Tyr861) following 6 hours of attachment to fibronectin. Ethanol pretreatment further increased pFAK (Tyr861); the increase also depended on the duration of cell attachment to fibronectin. Ethanol did not affect pFAK (Tyr397) (Fig. 2D). Ethanol-induced phosphorylation of ErbB2 and FAK was verified by immunofluorescent staining and some colocalizations of phosphorylated ErbB2 and FAK were observed (Fig. 2F). FAK is a substrate of cSrc, and FAK Tyr861 is a major site of phosphorylation by Src kinase (Vadlamudi et al., 2003). We therefore examined the effect of ethanol on cSrc. Ethanol increased the phosphorylation of cSrc at Tyr216, but not at Tyr416 (Fig. 2D,E). These results were consistent with published results showing that ErbB2 signals selectively upregulate phospho-cSrc (Tyr216) and phospho-FAK (Tyr861) (Kuramochi et al., 2006; Vadlamudi et al., 2003).

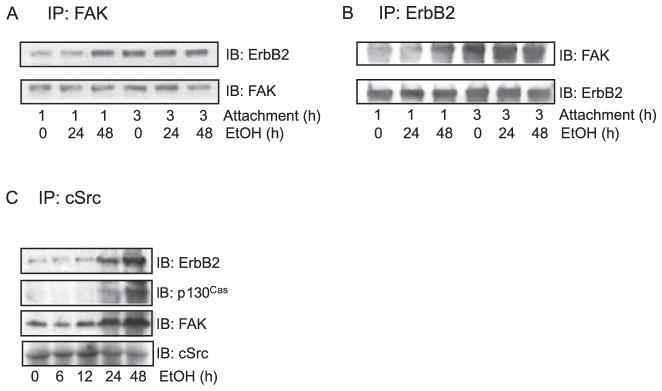

Ethanol Promotes the Interaction Among ErbB2, FAK, and cSrc

Because ethanol increased the phosphorylation of ErbB2, FAK, and cSrc, we examined the effect of ethanol on their interaction. MCF7ErbB2 cells were pretreated with ethanol (0 or 400 mg/ dl) for 24 or 48 hours and seeded on fibronectin-coated culture dishes, allowing 1 or 3 hours for attachment. The association between ErbB2 and FAK was determined by their co-immunoprecipitation. ErbB2 /FAK interaction depended on the duration of cell attachment to fibronectin (Fig. 3A,B). In untreated cells, ErbB2/FAK association was much stronger after 3-hour attachment than after 1 hour. Ethanol-induced increase in ErbB2/FAK association was only observed in cells that were pretreated with ethanol for 48 hours and allowed to attach for 1 hour. In the group of 3-hour attachment, ErbB2/FAK association was strong and ethanol pretreatment did not further increase their association.

Fig. 3.

Effect of ethanol on the interactions among ErbB2, FAK, and cSrc. MCF7ErbB2 cells were pretreated with ethanol (0 or 400 mg / dl) for 24 or 48 hours and seeded on fibronectin-coated culture wells, allowing attachment for 1 or 3 hours. (A) Cell lysates were collected and immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-FAK antibody, then immunoblotted (IB) with an anti-ErbB2 or anti-FAK antibody. (B) Cell lysates were collected and IP with an anti-ErbB2 antibody and IB with an anti-ErbB2 or anti-FAK antibody. (C) Cells were pretreated with ethanol (0 or 400 mg/ dl) for indicated times and allowed attachment for 3 hours. Cell lysates were collected and immunoprecipitated with an anti-cSrc antibody and immunoblotted with anti-ErbB2, p130Cas, FAK, or cSrc antibody. These experiments were replicated 3 times.

The formation of FAK/ cSrc complex is critical for further phosphorylation of FAK and necessary for triggering its downstream cell signaling, including the recruitment of paxillin and p130Cas. We next investigated the effect of ethanol on the formation of the FAK/ cSrc complex. FAK/ cSrc association was weak following 1 hour of attachment to fibronectin. Although we observed an ethanol-induced increase in FAK/ cSrc association following 1 hour of attachment, the results were inconclusive (data not shown). The effect of ethanol on FAK/ cSrc association was much more evident and consistent in cells that attached to fibronectin for 3 hours. We therefore present the data of 3-hour attachment in Fig. 3C. Ethanol pretreatment enhanced the association between FAK and cSrc. In addition, ethanol also promoted the co-immunoprecipitation of cSrc /ErbB2 and cSrc / p130Cas. Ethanol-promoted interaction among these proteins was duration dependent; the effect of 48-hour pretreatment was stronger than that of 24-hour pretreatment (Fig. 3C).

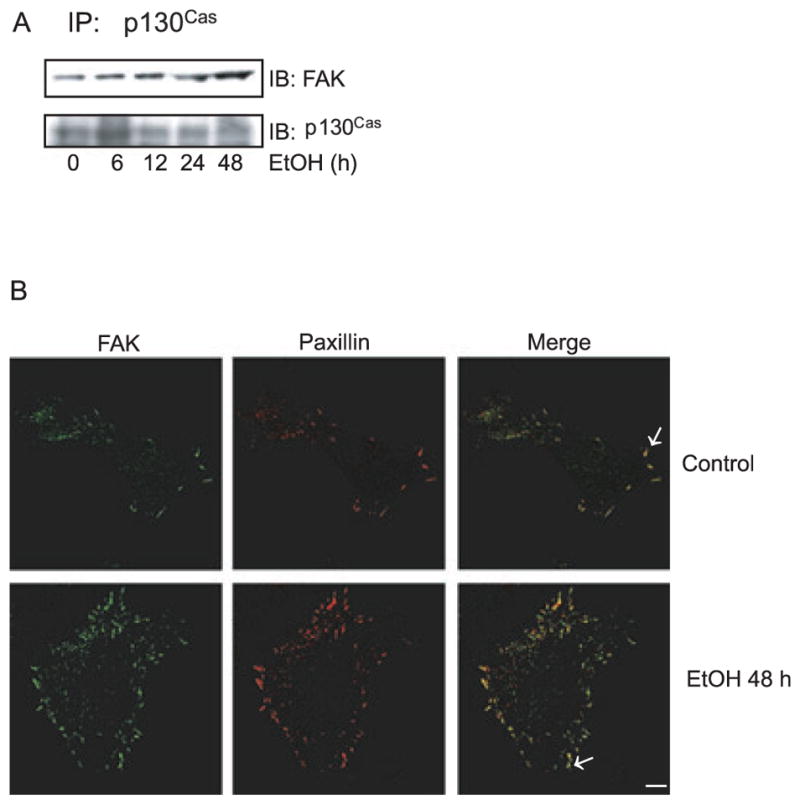

Ethanol Enhances the Formation of a Focal Complex

The activation of FAKleads to the recruitment of proteins to focal adhesion sites, forming a focal complex. Paxillin and p130Cas are 2 important components in the focal complex and are involved in many cellular activities including cell adhesion, motility, survival, and metastasis (Cox et al., 2006; Turner, 2000). Paxillin, an adapter protein, binds to the C-terminal domain of FAK through its leucine-rich motifs and is phosphorylated by FAK. As shown in Fig. 4A,B, ethanol pretreatment enhanced the association between p130Cas and FAK and increased the amount of focal adhesions that were visualized by FAK and paxillin immunoreactivity.

Fig. 4.

Effect of ethanol on focal complex. (A) MCF7ErbB2 cells were pretreated with ethanol (0 or 400 mg / dl) for indicated times and seeded on fibronectin-coated culture dishes. After 3 hours of attachment, cell lysates were collected and immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-p130Cas antibody, then immunoblotted (IB) with an anti-FAK antibody. (B) Cells were pretreated with ethanol (0 or 400 mg/ dl) for 48 hours and allowed to attach for 3 hours. The expression of FAK and paxillin was detected with immunofluorescent staining. Arrows indicate the co-localization of paxillin and FAK. Scale bar = 5 μm. The experiments were replicated 3 times.

p130Cas binds to the FAK-cSrc complex, forming a docking site for the recruitment of Crk, an adapter protein for numerous proteins involved in cell attachment /migration (Cox et al., 2006). Phosphorylation and activation of the Cas protein are FAK and cSrc dependent (Cox et al., 2006). Ethanol also increased p130Cas / cSrc association (Fig. 3C), indicating that ethanol promoted the binding of p130Cas to the FAK/ cSrc complex. Together, these data suggest that ethanol may enhance the formation of a focal complex that triggers signal transduction necessary for cell adhesion /migration.

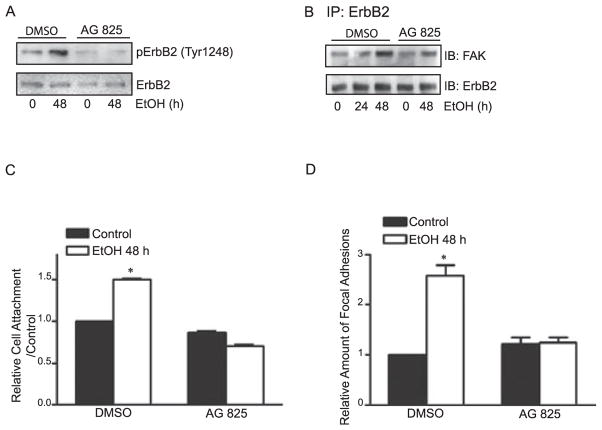

ErbB2 Inhibitor Blocks Ethanol-Induced Cell Adhesion

To determine whether the ethanol-mediated increase in formations of focal adhesions and cell /ECM interaction resulted from ErbB2 activation, we used a selective ErbB2 inhibitor Tyrphostin (AG825) to block ErbB2 activation. As shown in Fig.5A,B, AG825 effectively inhibited ethanol-induced phosphorylation of ErbB2 at Tyr1248 and ErbB2/FAK association. Moreover, AG825 completely blocked ethanol-enhanced adhesion of MCF7ErbB2 cells to fibronectin (Fig. 5C) and ethanol-stimulated formation of focal adhesions (Fig. 5D). These data suggest that ethanol-stimulated cell attachment and the formation of focal adhesions may be initiated by ErbB2 activation.

Fig. 5.

Effect of ErbB2 inhibitor AG825 on ethanol-induced cell adhesion. (A) MCF7ErbB2 cells were pretreated with ethanol (0 or 400 mg/ dl) with / without AG825 (5 μM in DMSO) for 48 hours. Cells were then seeded on fibronectin-coated culture dishes and allowed to attach for 1 hour. Cell lysates were collected and analyzed for the expression of phosphorylated ErbB2 (Tyr1248) with immunoblotting. Cells treated with vehicle (DMSO) only served as a control. (B) Cells were pretreated with ethanol (0 or 400 mg/ dl) with / without AG825 (5 μM in DMSO) for 24 or 48 hours. Cells were then seeded on fibronectin-coated culture dishes and allowed to attach for 1 hour. Cell lysates were collected and immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-ErbB2 antibody, then immunoblotted (IB) with anti-FAK or ErbB2 antibodies. (C) MCF7ErbB2 cells were pretreated with ethanol (0 or 400 mg/ dl) with / without AG825 (5 μM in DMSO) for 48 hours. Cells were then seeded on fibronectin-coated culture dishes and allowed to attach for 3 hours. Cell adhesion was quantified as described in Fig. 1A. (D) Focal adhesions were detected with paxillin immunoreactivity and counted randomly on 10 or more cells as described in Fig. 1B. The mean of focal adhesions per cell ± SEM was calculated and expressed relative to untreated controls. These experiments were replicated 3 times. *Significant difference from untreated controls.

DISCUSSION

Excessive ethanol exposure is implicated in enhanced metastasis of breast cancer. Experimental studies support that ethanol promotes migration / invasion of breast cancer cells. Our previous data indicates that ethanol preferably stimulates the migration / invasion of breast cancer cells over-expressing ErbB2 (Aye et al., 2004; Ke et al., 2006; Ma et al., 2003). Adhesion to extracellular matrix is the initial step for cancer cell migration/ invasion and plays an important role in metastasis (van Nimwegen and van de Water, 2007). We demonstrate here that ethanol enhances the adhesion of MCF7 cells over-expressing ErbB2 to fibronectin. Ethanol promotes the interaction between ErbB2 and FAK and increases the expression of a focal adhesions. Ethanol enhances the formation of focal complex. Inhibition of ErbB2 activation is sufficient to block the ethanol-induced increase in cell adhesion as well as the formation of focal adhesions.

Ethanol-stimulated cell adhesion likely results from alterations in ErbB2-initiated intracellular signaling rather than a direct change in the ECM, because ethanol does not increase the adhesion of MCF7 cells. In addition, ethanol induces ErbB2 phosphorylation, and blocking ErbB2 activation by a selective inhibitor eliminates ethanol-mediated ErbB2 /FAK association and subsequent cell adhesion. It is unclear how ethanol activates ErbB2. Currently, there is no identified ligand for ErbB2; the activation of ErbB2 may be mediated by autophosphorylation in cells over-expressing ErbB2 or transactivation through interaction with other members of the ErbB family.

Our results indicate that ethanol induces ErbB2 phosphorylation without affecting its expression levels in MCF7ErbB2 cells. The expression/phosphorylation of ErbB2 in parental MCF7 cells is low and we do not observe any alterations in either ErbB2 expression or phosphorylation in these cells following ethanol exposure (data not shown). ErbB2 may be transactivated by forming heterodimers with othermembers of the ErbB family such as EGFR or ErbB3/ 4. It is reported that ethanol increases the amount of EGFR on the cell membrane bydecreasing its internalization infetal hepatocytes (Henderson et al., 1989). Chronic ethanol exposure increases immunoreactivity of EGFR and ErbB2 in murine prenatal tooth tissue (Jimenez-Farfan et al., 2005). It remains to be determined whether ethanol affects other members of the ErbB2 family or promotes the interaction among ErbB2 and these members.

Ethanol exposure may induce the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in mammary tissues, and ethanol-mediated ROS production is considered a potential mechanism for its promotion of mammary tumors (Castro et al., 2001; Wright et al., 1999). It has been reported that ROS is involved in the activation of EGFR (Chen et al., 2006; Forsyth et al., 2007; Meng et al., 2002; von et al., 2006). We have previously demonstrated that ethanol stimulates ROS production in mammary epithelial cells in an ErbB2-dependent manner; that is, ethanol produces more ROS accumulation in cells over-expressing ErbB2 than cells with lower levels of ErbB2 (Ma et al., 2003). We further reveal that antioxidants are effective in ameliorating ethanol-induced invasion of breast cancer cells over-expressing ErbB2 (Ke et al., 2006). It is currently unclear whether ethanol-induced ROS production is involved in ErbB2 activation.

FAK plays an important role in ErbB2/ErbB3-induced oncogenesis and invasiveness of breast cancer (Benlimame et al., 2005). ErbB2 signaling regulates focal adhesions in a FAK- and Src-dependent manner in breast cancer cells (Xu et al., 2009). We show that ethanol induces ErbB2/ FAK association and FAK phosphorylation at Tyr861 as well as cSrc at Tyr216. This is consistent with previous findings that show heregulin-induced activation of ErbB2 selectively upregulates phosphorylation of FAK at Tyr861 and cSrc at Tyr215 in breast cancer cells (Vadlamudi et al., 2002, 2003). Phosphorylation of FAK at Tyr861 plays an important role in the invasion of breast cancer cells (Earley and Plopper, 2008). In patients with breast cancer, over 50% of breast tumors with ErbB2 over-expression exhibit elevated levels of phospho-FAK (Tyr861) and phospho-Src (Tyr215) (Schmitz et al., 2005). In addition, ErbB2 and phospho-FAK are co-expressed in about 53% of metastatic cells of patients with breast cancer (Kallergi et al., 2007). FAK regulates cell adhesion to the ECM that is also important for cell survival (van Nimwegen and van de Water, 2007). Inhibition of FAK results in cell detachment and apoptosis of breast cancer cells (Beviglia et al., 2003). Therefore, ethanol-promoted cell adhesion to ECM is likely mediated by FAK activation.

It is interesting to note the ethanol-induced increase in ErbB2 /FAK association is only observed in cells that attach to fibronectin for 1 hour, but not in cells that are allowed to attach for 3 hours (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, ethanol-promoted cell adhesion and FAK phosphorylation are observed in cells that have attached to fibronectin for 1 to 6 hours (Fig. 2). Ethanol-stimulated cSrc /ErbB2 and cSrc /FAK association is evident following 3 hours of attachment (Fig. 3C). This suggests that ErbB2/FAK association depends on cell /ECM interaction, and the binding between ErbB2 and FAK saturates after 3 hours of attachment. The association of cSrc /ErbB2 or cSrc /FAK, however, is not saturated; therefore, ethanol-enhanced cSrc /FAK association further phosphorylates FAK. Together, the results imply that ErbB2 /FAK interaction is an initial step that regulates ethanol-mediated cell adhesion.

FAK regulates diverse intracellular signaling pathways and is involved in various cellular activity. Our results demonstrate that ethanol induces the formation of focal complexes in which FAK, paxillin, and p130Cas are important components. Paxillin is a scaffold / adaptor protein that interacts with FAK, Src, vinculin, and Crk in a focal complex and is involved in actin cytoskeleton organization necessary for cell migration and tumor metastasis (Turner, 2000). Association of p130Cas with activated FAK leads to the formation of a FAK-Src-Cas-Crk complex that directly regulates cell migration (Cox et al., 2006). FAK also participates in MAPK signaling cascades and regulates the activity of p38 MAPK and JNKs (Aikawa et al., 2002; Cox et al., 2006). We have previously demonstrated that p38MAPK and c-Jun NH2 terminal protein kinases (JNKs) play an important role in ethanol-induced migration/ invasion of breast cancer cells (Ma et al., 2003). Therefore, ethanol-mediated activation of FAK may be upstream of p38MAPK and JNK activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jian Jian Li (Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN) for providing MCF7ErbB2 cells. This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AA01540 and AA017226).

References

- Aikawa R, Nagai T, Kudoh S, Zou Y, Tanaka M, Tamura M, Akazawa H, Takano H, Nagai R, Komuro I. Integrins play a critical role in mechanical stress-induced p38MAPK activation. Hypertension. 2002;39:233–238. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.102699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora P, Cuevas BD, Russo A, Johnson GL, Trejo J. Persistent transactivation of EGFR and ErbB2 /HER2 by protease-activated receptor-1 promotes breast carcinoma cell invasion. Oncogene. 2008;27:4434–4445. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aye MM, Ma C, Lin H, Bower KA, Wiggins RC, Luo J. Ethanol-induced in vitro invasion of breast cancer cells: the contribution of MMP-2 by fibroblasts. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:738–746. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai XM, Zhang W, Liu NB, Jiang H, Lou KX, Peng T, Ma J, Zhang L, Zhang H, Leng J. Focal adhesion kinase: important to prostaglandin E2-mediated adhesion, migration and invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2009;21:129–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey KM, Liu J. Caveolin-1 up-regulation during epithelial to mesenchymal transition is mediated by focal adhesion kinase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:13714–13724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709329200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benlimame N, He Q, Jie S, Xiao D, Xu YJ, Loignon M, Schlaepfer DD, aoui-Jamali MA. FAK signaling is critical for ErbB-2 / ErbB-3 receptor cooperation for oncogenic transformation and invasion. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:505–516. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200504124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beviglia L, Golubovskaya V, Xu L, Yang X, Craven RJ, Cance WG. Focal adhesion kinase N-terminus in breast carcinoma cells induces rounding, detachment and apoptosis. Biochem J. 2003;373:201–210. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boffetta P, Hashibe M. Alcohol and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:149–156. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70577-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro GD, Delgado de Layno AM, Costantini MH, Castro JA. Cytosolic xanthine oxidoreductase mediated bioactivation of ethanol to acetaldehyde and free radicals in rat breast tissue. Its potential role in alcohol-promoted mammary cancer. Toxicology. 2001;160:11–18. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(00)00433-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Cheng TH, Lin H, Shih NL, Chen YL, Chen YS, Cheng CF, Lian WS, Meng TC, Chiu WT, Chen JJ. Reactive oxygen species generation is involved in epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation through the transient oxidization of Src homology 2-containing tyrosine phosphatase in endothelin-1 signaling pathway in rat cardiac fibroblasts. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1347–1355. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.017558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox BD, Natarajan M, Stettner MR, Gladson CL. New concepts regarding focal adhesion kinase promotion of cell migration and proliferation. J Cell Biochem. 2006;99:35–52. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earley S, Plopper GE. Phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase promotes extravasation of breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366:476–482. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan S, Meng Q, Gao B, Grossman J, Yadegari M, Goldberg ID, Rosen EM. Alcohol stimulates estrogen receptor signaling in human breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5635–5639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von MC, Fernau NS, Beier JI, Sies H, Klotz LO. Extracellular generation of hydrogen peroxide is responsible for activation of EGF receptor by ultraviolet A radiation. Free Radic BiolMed. 2006;41:1478–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth CB, Banan A, Farhadi A, Fields JZ, Tang Y, Shaikh M, Zhang LJ, Engen PA, Keshavarzian A. Regulation of oxidant-induced intestinal permeability by metalloprotease-dependent epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:84–97. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.113019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth CB, Tang Y, Shaikh M, Zhang L, Keshavarzian A. Alcohol stimulates activation of snail, epidermal growth factor receptor signaling, and biomarkers of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in colon and breast cancer cells. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:19–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01061.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graus-Porta D, Beerli RR, Daly JM, Hynes NE. ErbB-2, the preferred heterodimerization partner of all ErbB receptors, is a mediator of lateral signaling. EMBO J. 1997;16:1647–1655. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi C, Pisanti S, Laezza C, Malfitano AM, Santoro A, Vitale M, Caruso MG, Notarnicola M, Iacuzzo I, Portella G, Di MV, Bifulco M. Anandamide inhibits adhesion and migration of breast cancer cells. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanada M, Tanaka K, Matsumoto Y, Nakatani F, Sakimura R, Matsunobu T, Li X, Okada T, Nakamura T, Takasaki M, Iwamoto Y. Focal adhesion kinase is activated in invading fibrosarcoma cells and regulates metastasis. Clin ExpMetastasis. 2005;22:485–494. doi: 10.1007/s10585-005-3733-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson GI, Baskin GS, Horbach J, Porter P, Schenker S. Arrest of epidermal growth factor-dependent growth in fetal hepatocytes after ethanol exposure. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1287–1294. doi: 10.1172/JCI114296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izevbigie EB, Ekunwe SI, Jordan J, Howard CB. Ethanol modulates the growth of human breast cancer cells in vitro. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2002;227:260–265. doi: 10.1177/153537020222700406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Farfan D, Guevara J, Zenteno E, Malagon H, Hernandez-Guerrero JC. EGF-R and erbB-2 in murine tooth development after ethanol exposure. Birth Defects Res A ClinMol Teratol. 2005;73:65–71. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallergi G, Mavroudis D, Georgoulias V, Stournaras C. Phosphorylation of FAK, PI-3K, and impaired actin organization in CK-positive micrometastatic breast cancer cells. Mol Med. 2007;13:79–88. doi: 10.2119/2006-00083.Kallergi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassis JN, Guancial EA, Doong H, Virador V, Kohn EC. CAIR-1/BAG-3 modulates cell adhesion and migration by downregulating activity of focal adhesion proteins. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:2962–2971. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke Z, Lin H, Fan Z, Cai TQ, Kaplan RA, Ma C, Bower KA, Shi X, Luo J. MMP-2 mediates ethanol-induced invasion of mammary epithelial cells over-expressing ErbB2. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:8–16. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key J, Hodgson S, Omar RZ, Jensen TK, Thompson SG, Boobis AR, Davies DS, Elliott P. Meta-analysis of studies of alcohol and breast cancer with consideration of the methodological issues. Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:759–770. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramochi Y, Guo X, Sawyer DB. Neuregulin activates erbB2-dependent src /FAK signaling and cytoskeletal remodeling in isolated adult rat cardiac myocytes. JMol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacoste J, Aprikian AG, Chevalier S. Focal adhesion kinase is required for bombesin-induced prostate cancer cell motility. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2005;235:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix H, Iglehart JD, Skinner MA, Kraus MH. Overexpression of erbB-2 or EGF receptor proteins present in early stage mammary carcinoma is detected simultaneously in matched primary tumors and regional metastases. Oncogene. 1989;4:145–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J. Role of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in ethanol-induced invasion by breast cancer cells. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21(Suppl 3):S65–S68. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Lindstrom CL, Donahue A, Miller MW. Differential effects of ethanol on the expression of cyclo-oxygenase in cultured cortical astrocytes and neurons. J Neurochem. 2001;76:1354–1363. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Miller MW. Differential sensitivity of human neuroblastoma cell lines to ethanol: correlations with their proliferative responses to mitogenic growth factors and expression of growth factor receptors. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:1186–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Miller MW. Ethanol enhances erbB-mediated migration of human breast cancer cells in culture. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;63:61–69. doi: 10.1023/a:1006436315284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Lin H, Leonard SS, Shi X, Ye J, Luo J. Overexpression of ErbB2 enhances ethanol-stimulated intracellular signaling and invasion of human mammary epithelial and breast cancer cells in vitro. Oncogene. 2003;22:5281–5290. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKillop IH, Schrum LW. Alcohol and liver cancer. Alcohol. 2005;35:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng TC, Fukada T, Tonks NK. Reversible oxidation and inactivation of protein tyrosine phosphatases in vivo. Mol Cell. 2002;9:387–399. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00445-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Q, Gao B, Goldberg ID, Rosen EM, Fan S. Stimulation of cell invasion and migration by alcohol in breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;273:448–453. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Nimwegen MJ, van de Water B. Focal adhesion kinase: a potential target in cancer therapy. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73:597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden GR. Alcohol and oral cancer. Alcohol. 2005;35:169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens LV, Xu L, Craven RJ, Dent GA, Weiner TM, Kornberg L, Liu ET, Cance WG. Overexpression of the focal adhesion kinase (p125FAK) in invasive human tumors. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2752–2755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens LV, Xu L, Dent GA, Yang X, Sturge GC, Craven RJ, Cance WG. Focal adhesion kinase as a marker of invasive potential in differentiated human thyroid cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 1996;3:100–105. doi: 10.1007/BF02409059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT. Focal adhesion kinase: the first ten years. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1409–1416. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson MC, Dietrich KD, Danyluk J, Paterson AH, Lees AW, Jamil N, Hanson J, Jenkins H, Krause BE, McBlain WA. Correlation between c-erbB-2 amplification and risk of recurrent disease in node-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1991;51:556–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poschl G, Seitz HK. Alcohol and cancer. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39:155–165. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purohit V, Khalsa J, Serrano J. Mechanisms of alcohol-associated cancers: introduction and summary of the symposium. Alcohol. 2005;35:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrmann S, Linseisen J, Vrieling A, Boffetta P, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Lowenfels AB, Jensen MK, Overvad K, Olsen A, Tjonneland A, Boutron-Ruault MC, Clavel-Chapelon F, Fagherazzi G, Misirli G, Lagiou P, Trichopoulou A, Kaaks R, Bergmann MM, Boeing H, Bingham S, Khaw KT, Allen N, Roddam A, Palli D, Pala V, Panico S, Tumino R, Vineis P, Peeters PH, Hjartaker A, Lund E, Cornejo ML, Agudo A, Arriola L, Sanchez MJ, Tormo MJ, Barricarte GA, Lindkvist B, Manjer J, Johansson I, Ye W, Slimani N, Duell EJ, Jenab M, Michaud DS, Mouw T, Riboli E, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB. Ethanol intake and the risk of pancreatic cancer in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC) Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:785–794. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9293-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz KJ, Grabellus F, Callies R, Otterbach F, Wohlschlaeger J, Levkau B, Kimmig R, Schmid KW, Baba HA. High expression of focal adhesion kinase (p125FAK) in node-negative breast cancer is related to overexpression of HER-2 / neu and activated Akt kinase but does not predict outcome. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:R194–R203. doi: 10.1186/bcr977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz HK, Becker P. Alcohol metabolism and cancer risk. Alcohol Res Health. 2007;30:38–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz HK, Maurer B. The relationship between alcohol metabolism, estrogen levels, and breast cancer risk. Alcohol Res Health. 2007;30:42–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singletary K. Ethanol and experimental breast cancer: a review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:334–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire WL. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2 / neu oncogene. Science. 1987;235:177–182. doi: 10.1126/science.3798106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sood AK, Coffin JE, Schneider GB, Fletcher MS, DeYoung BR, Gruman LM, Gershenson DM, Schaller MD, Hendrix MJ. Biological significance of focal adhesion kinase in ovarian cancer: role in migration and invasion. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1087–1095. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63370-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer KS, Graus-Porta D, Leng J, Hynes NE, Klemke RL. ErbB2 is necessary for induction of carcinoma cell invasion by ErbB family receptor tyrosine kinases. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:385–397. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.2.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauchi K, Hori S, Itoh H, Osamura RY, Tokuda Y, Tajima T. Immunohistochemical studies on oncogene products (c-erbB-2, EGFR, c-myc) and estrogen receptor in benign and malignant breast lesions. With special reference to their prognostic significance in carcinoma. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1989;416:65–73. doi: 10.1007/BF01606471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjonneland A, Christensen J, Olsen A, Stripp C, Thomsen BL, Overvad K, Peeters PH, van Gils CH, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Ocke MC, Thiebaut A, Fournier A, Clavel-Chapelon F, Berrino F, Palli D, Tumino R, Panico S, Vineis P, Agudo A, Ardanaz E, Martinez-Garcia C, Amiano P, Navarro C, Quiros JR, Key TJ, Reeves G, Khaw KT, Bingham S, Trichopoulou A, Trichopoulos D, Naska A, Nagel G, Chang-Claude J, Boeing H, Lahmann PH, Manjer J, Wirfalt E, Hallmans G, Johansson I, Lund E, Skeie G, Hjartaker A, Ferrari P, Slimani N, Kaaks R, Riboli E. Alcohol intake and breast cancer risk: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18:361–373. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CE. Paxillin interactions. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 23):4139–4140. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.23.4139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadlamudi RK, Adam L, Nguyen D, Santos M, Kumar R. Differential regulation of components of the focal adhesion complex by heregulin: role of phosphatase SHP-2. J Cell Physiol. 2002;190:189–199. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadlamudi RK, Sahin AA, Adam L, Wang RA, Kumar R. Heregulin and HER2 signaling selectively activates c-Src phosphorylation at tyrosine 215. FEBS Lett. 2003;543:76–80. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00404-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaeth PA, Satariano WA. Alcohol consumption and breast cancer stage at diagnosis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:928–934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visvanathan K, Crum RM, Strickland PT, You X, Ruczinski I, Berndt SI, Alberg AJ, Hoffman SC, Comstock GW, Bell DA, Helzlsouer KJ. Alcohol dehydrogenase genetic polymorphisms, low-to-moderate alcohol consumption, and risk of breast cancer. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:467–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Nohara K, Olivera A, Thompson EW, Spiegel S. Involvement of focal adhesion kinase in inhibition of motility of human breast cancer cells by sphingosine 1-phosphate. Exp Cell Res. 1999;247:17–28. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watabiki T, Okii Y, Tokiyasu T, Yoshimura S, Yoshida M, Akane A, Shikata N, Tsubura A. Long-term ethanol consumption in ICR mice causes mammary tumor in females and liver fibrosis in males. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:117S–122S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrle-Haller B, Imhof B. The inner lives of focal adhesions. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:382–389. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss HA, Brinton LA, Brogan D, Coates RJ, Gammon MD, Malone KE, Schoenberg JB, Swanson CA. Epidemiology of in situ and invasive breast cancer in women aged under 45. Br J Cancer. 1996;73:1298–1305. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright RM, McManaman JL, Repine JE. Alcohol-induced breast cancer: a proposed mechanism. Free Radic BiolMed. 1999;26:348–354. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00204-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Benlimame N, Su J, He Q, Alaoui-Jamali MA. Regulation of focal adhesion turnover by ErbB signalling in invasive breast cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:633–643. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Waters CL, Hu C, Wysolmerski RB, Vincent PA, Minnear FL. Sphingosine 1-phosphate rapidly increases endothelial barrier function independently of VE-cadherin but requires cell spreading and Rho kinase. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1309–C1318. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00014.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]