Abstract

Introduction: Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are novel candidates in nanotechnology with a variety of increasing applications in medicine and biology. Therefore the investigation of nanomaterials’ biocompatibility can be an important topic. The aim of present study was to investigate the CNTs impact on cardiac heart rate among rats.

Methods: Electrocardiogram (ECG) signals were recorded before and after injection of CNTs on a group with six rats. The heart rate variability (HRV) analysis was used for signals analysis. The rhythm-to-rhythm (RR) intervals in HRV method were computed and features of signals in time and frequency domains were extracted before and after injection.

Results: Results of the HRV analysis showed that CNTs increased the heart rate but generally these nanomaterials did not cause serious problem in autonomic nervous system (ANS) normal activities.

Conclusion: Injection of CNTs in rats resulted in increase of heart rate. The reason of phenomenon is that multiwall CNTs may block potassium channels. The suppressed and inhibited IK and potassium channels lead to increase of heart rate.

Keywords: Carbon nanotubes, ECG signal, Heart function, MWCNT, RR interval

Introduction

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) with their special properties are regarded as unique materials in various health fields such as biomedicine and pharmacology.1 Recently, the potential application of CNTs in drug and gene delivery has been clearly demonstrated (e. g. drugs are encapsulated in CNTs, and then they are injected into cell and are released there).2 Furthermore, CNTs are promising candidates for forming the basis of new biological and medical devices such as pace makers and biosensors.3 For example, the CNT-based electrochemical biosensors have been used for detecting chemical redox interactions.4,5 Additionally, CNTs are used as scaffolds to promote cell adhesion, growth, differentiation, and proliferation. These scaffolds provide mechanical strength, chemical stability, and biological inertness.5 Another application of CNTs can be intracellular and extracellular recording.6,7

The benefits and the utilizations of CNTs may raise concerns about their biocompatibility and possible adverse effects on cardiovascular system.8 They may alter the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and spontaneous heart rate variability (HRV).8 According to inhalation studies on particles, it has been predicted that nano-sized particles will have higher pulmonary depositions and biological activities compared with larger particles. Therefore, some nanomaterials may affect the deposition site and distant responses throughout the body.9

In general, the cytotoxicity of CNTs depends on their structure, dose, concentration, manufacturing method, functional group, etc.10 Several in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that CNTs might induce oxidative stress and cytotoxic effects.10 These nanomaterials may cause pulmonary inflammation.10 The investigation of cardiovascular adverse effects of single-wall carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) on respiratory exposure shows that they lead to formation of pulmonary granulomatous and production of cardiovascular toxicity.11 A toxicity investigation of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) in human shows that not only they induce inflammatory and fibrotic reactions but also they lead to protein exudation and granulomas on the peritoneal side of the diaphragm.12 One of the in vitro studies about CNTs cardiovascular effects showed that exposure to CNTs increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases by affecting normal cardiac electrophysiology.13

Another study shows that oropharyngeal aspiration of MWCNT causes increased susceptibility of cardiac tissue to ischemia/reperfusion injury without a significant pulmonary inflammatory response; therefore MWCNTs can be the cardiovascular system risk.14 Generally, there is concern that nanomaterials could have a major impact on the cardiovascular system, although the effects of exposure to newly developed nanomaterials on the cardiovascular system remain elusive and no definitive data are available about these nanomaterials’ effect on the cardiovascular autonomic control.8,15 Inhaled nanoparticles in the lungs may cause systematic inflammation through oxidative stress, which mediates endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. In addition, nanoparticles can translocate into the blood stream, be taken up by endothelial cells, and directly induce injury of endothelial cells.15

Among all previous works, there are rarely studies about the cardiac effect of MWCNTs in rats during electrocardiogram (ECG) analysis. As it was mentioned earlier, the aim of present study was to investigate the CNTs’ effect on the heart of rats. The ECG represents the cardiac electrical activity. A typical ECG tracing is a repeating cycle of three electrical entities: a P wave (atrial depolarization), a QRS complex (ventricular depolarization), and a T wave (ventricular repolarization). They are measured by electrodes in typical engagement.16 ECG analysis represents the heart function, and changes during a kind of activity or the state of ANS are evaluated by means of ECG analysis. Therefore, to investigate the biocompatibility of CNTs in ANS activity, the ECG signals are considered. Recording is done before and after injection of CNTs. Time and frequency domain features for analyzing ECG signals were used in terms of HRV. The rhythm-to-rhythm (RR) intervals in HRV method were computed and features of signals in time and frequency domains were extracted pre- and post-injection. Finally results were discussed and the conclusion was done.

Materials and methods

Characteristics of animals

The experiment was carried out on male Wistar rats weighing 280 g to 300 g and each group included six rats. Animals were housed in standard polropylene cages, three per cage, under a 12:12 h light/dark cycle at an ambient temperature of 22±2°C and had free access to food and water. All experiments were carried out under ethical guidelines of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, for the care and use of laboratory animals (National Institutes of Health Publication No 85-23, revised 1985).

Chemical materials

For this study, functionalized MWCNTs with carboxyl group were used. They were purchased from Neutrino Company (Tehran, Iran). These functionalized MWCNTs were in solid powder and black color. COOH content of this material was 2 wt %. They had an inner diameter of 5 to 10 nm, an outer diameter of 10 to 20 nm, and an individual length of ~30 µm according to the manufacturer. Their purity was more than 95 wt %.

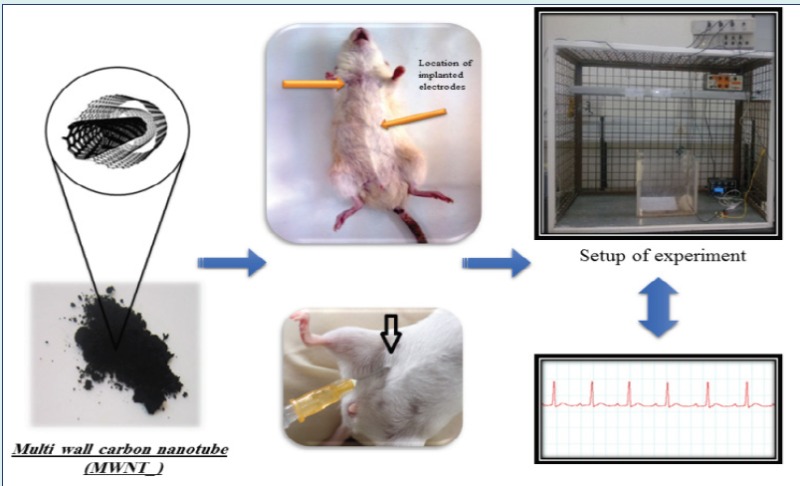

Surgical procedure

Rats were anaesthetized with injection of ketamine (80 mg/kg, i.p) and xylazine (20 mg/kg, i.p.). For ECG recording, two electrodes were implanted under the skin and ECG signal was acquired from lead II (voltage between the right arm and the left leg). The ECG electrodes (BP disposable chest electrodes) were soldered to copper wires. To prevent the wire damaging by the rat, they were conducted subcutaneously to back of the body.

Injection and ECG recording

Three days after the surgery, animals were settled in Faraday cage in a freely moving condition for ECG signal recording. In electrophysiology, it is a very common method that the experimentalist records EEG or ECG signals for a few minutes before drug injection, then drug injection is performed and the recording is continued. After these stages, the recorded data from before and after drug injection is analyzed and compared with each other. Since the injection of saline as control group had no significant effect on EEG and ECG recording in pervious papers of our college,17-19 we used our prior data about the effect of saline injection. Therefore, we had no additional group for saline injection as control; the group before injection of CNT was considered as control group.

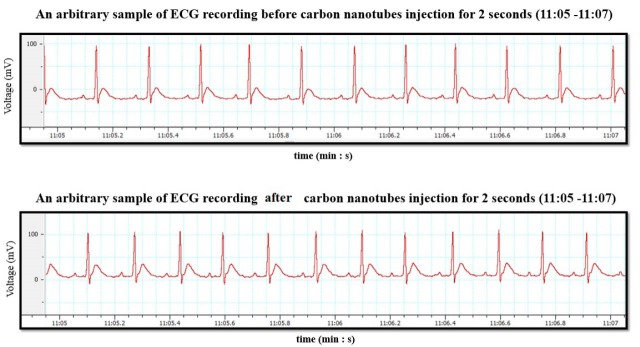

As mentioned above, the ECG signals were recorded for one hour, before CNT injection (as control group) and after it. For intra-peritoneal injecting of CNTs, 1 mg/kg body weight corresponding to 0.3 mg/rat of MWCNTs was considered. MWCNTs was dissolved in 0.9% saline for suspension and prepared at a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL and then it was injected to the rats. Half an hour after injection, ECG signals were recorded again for each rat. Fig. 1 shows an arbitrary sample of ECG recording, before and after CNT injection for 2 s from 11:05 to 11:07 (min: s).

Fig. 1 .

An arbitrary sample of ECG recording before and after CNT injection for 2 s, from 11:05 to 11:07 (min: s). (Top row) before CNT injection, (bottom row) after CNT injection.

ECG signal analysis

The HRV analysis method is used for ECG signals analysis. Before extraction features for signal analysis, a 45 Hz low pass filter was used for removing noise from the ECG data. HRV analysis was developed in order to assess ortho-sympathetic and parasympathetic influences.20 Analyzing HRV is a powerful tool to evaluate and investigate cardiac heart rate.21,22 The interval between adjacent QRS complexes in ECG signal is termed as the RR interval. The variation of RR interval is referred to be as the HRV.23

Each R peak, due to sinus depolarization, was detected from a continuous ECG signal, and the normal RR intervals were determined. Then they were analyzed in time and frequency domains. In the time domain analysis, the intervals between adjacent normal R peaks were measured over the period of recording. A variety of statistical parameters were calculated from the intervals.24

In frequency domain, Welch’s method was considered to calculate the power spectral density (PSD) of RR intervals.25 One of the important statistical parameters in frequency domain was the ratio of power in the low-frequencies (LFs) to the power in high frequencies (HFs). Study of HRV in time and frequency domains were done for the RR intervals of rats former and later to injection of CNTs.

Time domain analysis

Time domain analysis of selected RR included mean of RR interval series RRmean, standard deviation of all NN intervals (SDNN), the root mean square of differences of successive RR intervals (RMSSD), and mean heart rate (HRmean). There were N numbers of RR intervals in a segment.

Frequency domain analysis

HRV displays two main frequency components that represent ANS activity: a LF component which demonstrates both sympathetic and vagal activation and a HF component that indicates parasympathetic activity. The higher power of LF indicates high stress and the higher power of HF indicates low stress. The LF/HF ratio or the fractional LF power has been used to describe sympathovagal balance.26 Welch’s method is used for determining PSD of signals. The LF and HF frequency bands of the RR intervals were set at 0.4–1.5 Hz and 1.5– 5 Hz, respectively. The power of LF and HF frequency bands was computed using Welch’s method, then LFnorm and HFnorm were calculated which is as Eqs.1 and 2:

| (1) |

| (2) |

The LFnorm indicates the LF power and the HFnorm shows the HF power in normalized unit. The sympathovagal balance (LFnorm/ HFnorm ratio) is computed through dividing Eq.1 by Eq.2.

Statistical analysis

In this study, for statistical analysis, the SPSS software was used. To test the differences in behavioral experiment, the paired sample t test was done on results of HRV analysis.

Results and Discussion

Results of ECG analysis using HRV method

HRV features in time and frequency domains were calculated for RR intervals. Table 1 shows LFnorma_i/ HFnorma_i and LFnormb_i/ HFnormb_i ratios for a_i and b_i cases ( the “after” and “before injection” words are indicated by a_i and b_i indexes, respectively).

Table 1 . Paired samples statistics for frequency domain features .

| Name | Mean | Number | SD | P | |

| HFnorm* | HFnormb_i | 0.84 | 6 | 0.133 | 0.457 |

| HFnorma_i | 0.88 | 6 | 0.105 | ||

| LFnorm** | LFnormb_i | 0.16 | 6 | 0.133 | 0.475 |

| LFnorma_i | 0.12 | 6 | 0.105 | ||

| LFnorm/HFnorm | LFnormb_i/ HFnormb_i | 0.23 | 6 | 0.261 | 0.484 |

| LFnorma_i/ HFnorma_i | 0.15 | 6 | 0.151 |

*High-frequency; ** Low-frequency.

Norm is pointed to normal time.

The “after” and “before injection” words are indicated by a_i and b_i indexes, respectively.

According to Table 1, it was seen that for RR intervals, the mean of LFnorma_i and LFnorma_i/ HFnorma_i ratio were lower than LFnormb_i and LFnormb_i/ HFnormb_i ratio, respectively. On the other hand, the mean of HFnorma_i was higher than HFnormb_i , though differences for all of them were not significant (p>0.05). These results showed that CNTs were not change sympathovagal balance and therefore these nanomaterials did not make any problem in ANS activity. The results of RR intervals analysis in the time domain is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2 . Paired samples statistics for time domain features .

| Name | Mean | Number | SD | P | |

| HRmean* | HRmeanb_i | 360.13 | 6 | 30.292 | 0.062 |

| HRmeana_i | 323.61 | 6 | 26.267 | ||

| RRmean** | RRmeanb_i | 0.17 | 6 | 0.014 | 0.004 |

| RRmeana_i | 0.19 | 6 | 0.011 | ||

| RMSSD*** | RMSSDb_i | 0.01 | 6 | 0.002 | 0.338 |

| RMSSDa_i | 0.01 | 6 | 0.004 | ||

| SDNN**** | SDNNb_i | 0.01 | 6 | 0.002 | 0.758 |

| SDNNa_i | 0.01 | 6 | 0.003 |

* Mean heart rate; **Mean of RR interval series; *** The root mean square of differences of successive RR intervals.

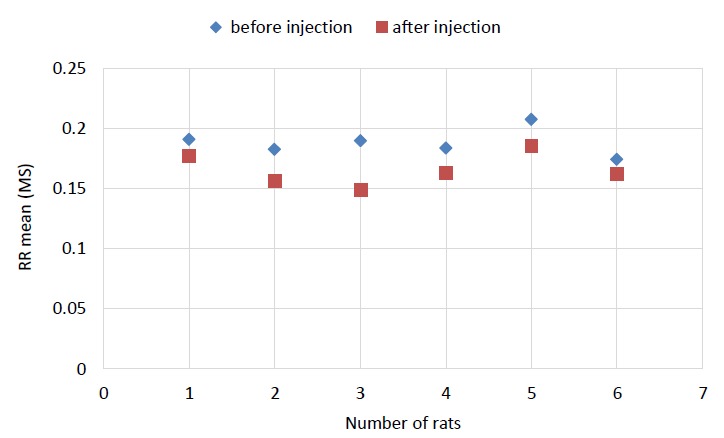

In Table 2, the results of RR intervals analysis are presented for CNT injection group (a_i) and control group (b_i). The results of before and after injection for these two factors showed that the values of SDNNa_i are lower than SDNNb_i and RMSSDa_i are higher than RMSSDb_i. The differences of these factors were not significant (p>0.05 for both). The differences of mean values were more than 10-2, but because of restriction of software, values were rounded up to 2 correct significant digits; therefore, Table 2 shows that the mean values of SDNNa_i and SDNNb_i and also RMSSDa_i and RMSSDb_i were equal. In RMSSD results, it was seen that CNTs did not significantly increase the stress. The result of RRmean analysis was significant (p=0.004). These results for a group of rats including former and later to injection of CNTs are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 .

RRmean plot for each rat (** p=0.004). It is shown that the mean of RR intervals measures is decreased after injection.

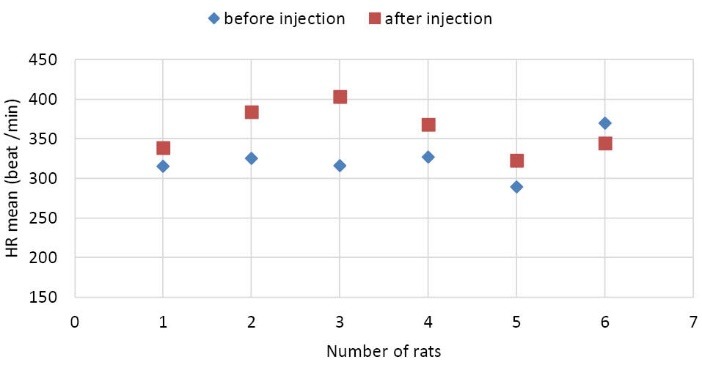

As it is shown in Fig. 2, the value of RRmeana_i was higher than RRmeanb_i. The p value for HRmean was 0.062 (this value was lower than 0.1, hence it was considered significant). These results for a group of rats including former and later to injection of CNTs are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3 .

HRmean plot for each rat (* p = 0.062). It is shown that the heart rate or the number of beats is decreased after injection.

As it is shown in Fig. 3, the value of HRmeanb_i was higher than HRmeana_i and the value of HRmean for rats was increased after injection. Analysis of these features showed that injection of CNTs increased the numbers of heart beats.

CNTs, according to their electrical, chemical, optical, mechanical, and thermal properties, have different applications in medicine, including the application in drug and gene delivery, as substrates or scaffolds for neuronal growth and so on. But the application of CNTs in medicine is closely dependent on their biocompatibility with body system.27 There are a few reports about biocompatibility of these nanomaterials.

Initial toxicological studies demonstrated that pharyngeal installation of SWCNT suspension in mice caused a persistent accumulation of CNT aggregates in the lung. It is followed by the rapid formation of pulmonary granulomatous, functional respiratory deficiencies and fibrotic tissues at the site.28,29 Some animal studies demonstrated that inflammatory and granulomatous responses are seen in the lung following exposure to CNTs.29-31 Different surfactants affect biocompatibility of CNTs. Investigation of the cytotoxicity of CNT dispersed in different surfactants showed that cytotoxicity of CNTs depends on surfactant selection; for example, SDBS (Sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate) led to toxicity and SC (sodium cholate) did not cause toxicity.32,33 Studying the effect of functionalized MWCNTs by -COOH on the potassium (K+) channels (Ito, IK, IK1) showed that MWCNTs suppress the K+ channels activity. On the other hand, Suppression of potassium channels did not associate with an induction of oxidative stress.34 The CNTs blocked the potassium channel pore and interrupted ion permeability. Similarity, CNTs caused a significant impairment in cytoplasm elevation when neurons were depolarized; this may be due to CNTs interfering with the function of channels.35 Recent study about effect of CNTs in cardiovascular system shows that pulmonary instillation MWCNT has the potential to cause cardiovascular abnormality. This study demonstrated that pulmonary exposure to MWCNT can be manifested as a reduced epithelial barrier and activator of vascular gp130-associated transsignaling; however the mechanism of CNT’s effects are unclear.36 In vitro tests investigation showed that MWCNTs were biocompatible, and no damage at the cellular structural level was observed.37 According to one of previous works, injection of MWCNTs led to a transient and self-limiting local inflammatory response.38 Generally, MWCNTs were reported to be more biocompatible than SWCNTs; therefore, they had more utility than SWCNTs for medical applications.39

As we know, potassium has the most important intracellular action, and it has a major role in determining the resting membrane potential of cells. Changes in potassium gradient across the cell membrane can result in cell dysfunction. This may mostly affect cardiovascular, resulting in cardiac arrhythmias. Potassium concentration changes in serum may occur as hyperkalemia and hypokalemia. Hypokalemia leads to shifting the cell resting membrane potential towards positive values and prolong the potential duration of the action and refractory period which are potentially arrhythmogenic.40 Hypokalemia increases the risk of developing ventricular arrhythmias such as ventricular tachycardia post myocardial infarction ventricular ectopic beats, and ventricular fibrillation.41 Hyperkalemia results in loss of resting membrane potential and reduction of potential action duration. When extracellular K+ was raised to levels around 15 mM, ventricular fibrillation occurred.42

The results of this study showed that injection of CNT increases the heart rate. It is obtained by investigating the results of two factors including HRmean and RRmean. The MWCNTs could be a potassium channel blocker. The mechanism that was involved in increasing the heart rate was probably suppressed and potassium channels was inhibited by MWCNTs. They led to a change in activating potential of mentioned potassium channels in direction of depolarization.

Conclusion

There is a potential concern about biocompatibility of CNTs in body function. Cardiac effect of MWCNTs in rat was studied in this paper. Effects of MWCNTs on ECG signals in one group of rats were investigated former and later to injection of CNTs. Analyses of the RR interval variability for ECG signals were done former and later to injection in time and frequency domains. According to the results obtained in frequency domain, MWCNTs did not affect the sympathovagal balance significantly. On the other hand, the results of HRV method in time domain showed that injection of CNTs increased the heart rate. The reason for this phenomenon was the possible inhibition of Ito, IK, and IK1 potassium channels by MWCNTs. In general, nanotubes do not cause serious problem in ANS normal activities, however they are not completely biocompatible on the heart.

Acknowledgments

This short communication is part of MSc thesis by research project of M. Hosseinpour. Authors would like to thank the reviewers’ comments on this submission, Tabriz University for financial supports and Neuroscience Research Center of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for experimental supports.

Ethical approval

There is none to be declared.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Study Highlights

What is current knowledge?

√ CNTs with their special properties have the potential application in biomedicine, pharmacology, and neurosciences.

√ There is a potential concern about biocompatibility of CNTs in body function.

√ The CNTs’ impact in ANS is investigated by ECG signals analysis.

What is new here?

√ CNTs do not affect the sympathovagal balance significantly.

√ Injection of CNTs into rats’ body resulted in increase of heart rate.

√ In general, nanotubes do not cause serious problem in ANS normal activities, however they are not completely biocompatible on the heart.

References

- 1.Bianco A, Kostarelos K, Prato M. Applications of carbon nanotubes in drug delivery. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9:674–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nunes A, Amsharov N, Guo C, Van den Bossche J, Santhosh P, Karachalios TK. et al. Hybrid Polymer‐Grafted Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes for In vitro Gene Delivery. Small. 2010;6:2281–91. doi: 10.1002/smll.201000864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nunes A, Al-Jamal K, Nakajima T, Hariz M, Kostarelos K. Application of carbon nanotubes in neurology: clinical perspectives and toxicological risks. Arch Toxicol. 2012;86:1009–20. doi: 10.1007/s00204-012-0860-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang W, Thordarson P, Gooding JJ, Ringer SP, Braet F. Carbon nanotubes for biological and biomedical applications. Nanotechnology. 2007;18:412001. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/18/41/412001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher C, Rider AE, Han ZJ, Kumar S, Levchenko I, Ostrikov K. Applications and nanotoxicity of carbon nanotubes and graphene in biomedicine. J Nanomater. 2012;2012:3. doi: 10.1155/2012/315185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoon I, Hamaguchi K, Borzenets IV, Finkelstein G, Mooney R, Donald BR. Intracellular neural recording with pure carbon nanotube probes. PloS One. 2013;8:e65715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walvekar R, Siddiqui MK, Ong S, Ismail AF. Application of CNT nanofluids in a turbulent flow heat exchanger. J Exp Nanosci. 2016;11:1–17. doi: 10.1080/17458080.2015.1015461. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Legramante JM, Sacco S, Crobeddu P, Magrini A, Valentini F, Palleschi G. et al. Changes in cardiac autonomic regulation after acute lung exposure to carbon nanotubes: Implications for occupational exposure. J Nanomater. 2012;2012:397206. doi: 10.1155/2012/397206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oberdörster G, Oberdörster E, Oberdörster J. Nanotoxicology: an emerging discipline evolving from studies of ultrafine particles. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:823–39. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kayat J, Gajbhiye V, Tekade RK, Jain NK. Pulmonary toxicity of carbon nanotubes: a systematic report. Nanomedicine. 2011;7:40–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Z, Hulderman T, Salmen R, Chapman R, Leonard SS, Young S-H. et al. Cardiovascular effects of pulmonary exposure to single-wall carbon nanotubes. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:377–82. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller J, Huaux F, Moreau N, Misson P, Heilier JF, Delos M. et al. Respiratory toxicity of multi-wall carbon nanotubes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;207:221–31. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helfenstein M, Miragoli M, Rohr S, Müller L, Wick P, Mohr M. et al. Effects of combustion-derived ultrafine particles and manufactured nanoparticles on heart cells in vitro. Toxicology. 2008;253:70–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urankar RN, Lust RM, Mann E, Katwa P, Wang X, Podila R. et al. Expansion of cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury after instillation of three forms of multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2012;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-9-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ichihara S, Tada-Oikawa S, Suzuki Y, Wu W, Ichihara G. Effects of nanomaterials on cardiovascular system. Transactions of the Materials Research Society of Japan. 2014;39:373–8. doi: 10.14723/tmrsj.39.373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parák J, Havlík J. ECG signal processing and heart rate frequency detection methods. Proceedings of Technical Computing Prague. 2011;8:2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Es’haghi F, Shahabi P, Frounchi J, Sadighi M, Yousefi H. Investigation of ECG changes in absence epilepsy on WAG/Rij rats. Basic Clin Neurosci. 2015;6:123–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghamkhari NG, Shahabi P, Alipoor M, Ghaderi PF, Asghari M, Sadighi AM. Ethosuximide affects paired-pulse facilitation in somatosensory cortex of WAG\Rij rats as a model of absence seizure. Adv Pharm Bull. 2015;5:483–9. doi: 10.15171/apb.2015.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sadighi M, Shahabi P, Gorji A, Pakdel FG, Nejad GG, Ghorbanzade A. Role of L-and T-type calcium channels in regulation of absence seizures in Wag/Rij Rats. Neurophysiology. 2013;45:312–8. doi: 10.1007/s11062-013-9374-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huang TC, Ramaekers D, Lin J, Geest HD, Aubert AE, eds. Analysis of heart rate variability using power spectral analysis and nonlinear dynamics. Comput Cardiology 1994; 25-28 Sept; 1994.

- 21.Thireau J, Zhang B, Poisson D, Babuty D. Heart rate variability in mice: a theoretical and practical guide. Exp Physiol. 2008;93:83–94. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.040733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang YM, Shiao CC, Huang YT, Chen IL, Yang CL, Leu SC. et al. Impact of metabolic syndrome and its components on heart rate variability during hemodialysis: a cross-sectional study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15:16. doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0328-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heart rate variability standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Eur Heart J. 1996;17:354–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleiger RE, Stein PK, Bigger JT. Heart rate variability: measurement and clinical utility. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2005;10:88–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2005.10101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akselrod S, Gordon D, Ubel FA, Shannon DC, Berger A, Cohen RJ. Power spectrum analysis of heart rate fluctuation: a quantitative probe of beat-to-beat cardiovascular control. Science. 1981;213:220–2. doi: 10.1126/science.6166045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seyd PA, Ahamed VT, Jacob J, Joseph P. Time and frequency domain analysis of heart rate variability and their correlations in diabetes mellitus. Int J Biol Life Sci. 2008;4:24–7. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sucapane A, Cellot G, Prato M, Giugliano M, Parpura V, Ballerini L. Interactions between cultured neurons and carbon nanotubes: a nanoneuroscience vignette. J Nanoneurosci. 2009;1:10. doi: 10.1166/jns.2009.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lam CW, James JT, McCluskey R, Hunter RL. Pulmonary toxicity of single-wall carbon nanotubes in mice 7 and 90 days after intratracheal instillation. Toxicol Sci. 2004;77:126–34. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shvedova AA, Kisin ER, Mercer R, Murray AR, Johnson VJ, Potapovich AI. et al. Unusual inflammatory and fibrogenic pulmonary responses to single-walled carbon nanotubes in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L698–L708. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00084.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Medina C, Santos‐Martinez M, Radomski A, Corrigan O, Radomski M. Nanoparticles: pharmacological and toxicological significance. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;150:552–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oberdörster G, Maynard A, Donaldson K, Castranova V, Fitzpatrick J, Ausman K. et al. Principles for characterizing the potential human health effects from exposure to nanomaterials: elements of a screening strategy. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2005;2:1. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong L, Joseph KL, Witkowski CM, Craig MM. Cytotoxicity of single-walled ca rbon nanotubes suspended in various surfactants. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:255702. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/25/255702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dong L, Witkowski CM, Craig MM, Greenwade MM, Joseph KL. Cytotoxicity effects of different surfactant molecules conjugated to carbon nanotubes on human astrocytoma cells. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2009;4:1517–23. doi: 10.1007/s11671-009-9429-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu H, Bai J, Meng J, Hao W, Xu H, Cao JM. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes suppress potassium channel activities in PC12 cells. Nanotechnology. 2009;20:285102. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/28/285102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park KH, Chhowalla M, Iqbal Z, Sesti F. Single-walled carbon nanotubes are a new class of ion channel blockers. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50212–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310216200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson LC, Holland NA, Snyder RJ, Luo B, Becak DP, Odom JT. et al. Pulmonary instillation of MWCNT increases lung permeability, decreases gp130 expression in the lungs, and initiates cardiovascular IL-6 transsignaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2016;310:L142–L54. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00384.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bardi G, Tognini P, Ciofani G, Raffa V, Costa M, Pizzorusso T. Pluronic-coated carbon nanotubes do not induce degeneration of cortical neurons in vivo and in vitro. Nanomedicine. 2009;5:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Handel M, Alizadeh D, Zhang L, Kateb B, Bronikowski M, Manohara H. et al. Selective uptake of multi-walled carbon nanotubes by tumor macrophages in a murine glioma model. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;208:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirano S, Kanno S, Furuyama A. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes injure the plasma membrane of macrophages. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;232:244–51. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Helfant RH. Hypokalemia and arrhythmias. Am J Med. 1986;80:13–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nordrehaug J, Johannessen K, Von Der Lippe G. Serum potassium concentration as a risk factor of ventricular arrhythmias early in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1985;71:645–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.71.4.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morena H, Janse M, Fiolet J, Krieger W, Crijns H, Durrer D. Comparison of the effects of regional ischemia, hypoxia, hyperkalemia, and acidosis on intracellular and extracellular potentials and metabolism in the isolated porcine heart. Circ Res. 1980;46:634–46. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.46.5.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]